Original Article

Quantitative Evaluation of Yoga

Postures Using Image Processing and Hotelling’s ![]() Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analysis

|

1 Assistant Professor, GLS University (FOBA), Ahmedabad, India |

|

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The aim of this study is to use computer vision and statistical analysis to measure how yoga practice can improve body posture. A Python-based model was developed that can recognize different yoga poses from images and then create a 3D skeleton of the human body using landmark points. For each pose, twelve important landmarks such as shoulders, elbows, hips, and knees were identified, and angles were calculated to check the correctness of posture. To evaluate whether these landmarks showed improvement after one month of yoga practice, we applied Hotelling’s T² test, a multivariate statistical method that can detect overall changes across several joints at the same time. The results showed that some landmarks had significant differences before and after yoga, meaning that the posture became more aligned and balanced. This method provides an objective way of checking yoga progress instead of relying only on visual observation. The study demonstrates that by combining image processing with statistical testing, it is possible to give meaningful feedback to yoga practitioners, trainers, and even rehabilitation experts in a simple and scientific manner Keywords: Yoga Posture Analysis, Image

Processing, Computer Vision, 3D Skeleton Model, Landmark Detection,

Hotelling’s T² Test |

||

INTRODUCTION

Yoga encompasses a

broad spectrum of practices, from physical postures (asanas) and breathing

techniques (pranayama) to meditation and ethical living. Ancient texts such as

the Bhagavad Gita and Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras emphasize yoga as both a

practical discipline and a path to self-realization. In modern times, yoga’s

versatility enables adaptation for all ages and backgrounds—whether as a gentle

means for injury rehabilitation, a dynamic tool for fitness, or a structured

method to foster mindfulness. The surge in global popularity reflects its

accessibility and multifaceted contributions to individual and societal health.

Scientific studies

increasingly validate yoga’s role in addressing major modern challenges,

including stress, sedentary lifestyles, and rising chronic disease rates.

Consistent practice cultivates physical flexibility and strength, supports

heart health, and aids in metabolic balance. Breathwork and meditative elements

foster nervous system resilience by reducing sympathetic (fight-or-flight)

activity and enhancing parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) function, directly

impacting stress reduction, sleep quality, and immune competence. Regular yoga

sessions are linked with lower rates of hypertension, anxiety, depression, and

chronic pain. Emerging research also highlights yoga’s effect on improving

neuroplasticity, attention, memory, and emotional regulation.

Despite decades of

anecdotal and clinical evidence supporting yoga’s efficacy, rigorous

quantification—particularly of biomechanical improvements—remains

under-explored. Recent studies leverage image processing and computer vision

methods to objectively assess posture quality, symmetry, and improvements over

time. These advancements are crucial for bridging the gap between traditional

practice and evidence-based health promotion. Using tools like pose estimation

algorithms and landmark tracking, researchers and practitioners can now gain

precise, visual feedback on alignment and progress, providing tangible metrics

for personalized guidance and large-scale studies.

Yoga’s impact is

not restricted to individual health. Group practices encourage social cohesion,

foster supportive communities, and contribute to healthier workplaces and

educational environments. Public health initiatives increasingly recognize yoga

as a cost-effective, scalable intervention for enhancing population wellbeing

and reducing healthcare burden, especially in contexts where access to

conventional medical or psychological care may be limited.

Yoga continues to

evolve as a dynamic interface between tradition and innovation, embodying both

an ancient wisdom and a modern science of self-care and self-mastery.

STUDY OBJECTIVES

1)

Develop

a computer vision model to detect and classify yoga poses from static images

using advanced landmark detection frameworks.

2)

Apply

Mediapipe for extracting 32 body landmarks per image to enable accurate mapping

of joints and limbs for analysis.

3)

Compute

joint angles from landmark coordinates using the Pythagorean theorem and law of

cosines, providing quantitative alignment measures.

4)

Create

rule-based algorithms that classify poses by mapping joint angles to benchmark

ranges for automated recognition.

5)

Overlay

detected landmarks and pose labels onto images to visually validate algorithm

results.

6)

Evaluate

classification and angle estimation accuracy through comparative analysis of

before-and-after images, measuring improvements in alignment and posture.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Cramer

et al. (2013) conducted a meta-analysis investigating

yoga’s effects on depression, demonstrating significant mental health benefits.

Their broad literature screening supports yoga as a complementary therapy. Yet,

variability in study designs, yoga styles, and intervention durations presents

challenges for standardized conclusions, indicating a need for more uniform

future trials.

Jain et al. (2015) used image processing and machine learning

methods for yoga pose recognition, aiming to improve physical alignment through

software-guided feedback. Their work laid foundational groundwork for later

pose detection models. However, the study is constrained by limited

computational resources and simpler machine learning methods of the time, which

may reduce accuracy and robustness compared to recent deep learning-based

approaches.

Li and Goldsmith (2015) reviewed the effects of yoga on anxiety and

stress, consolidating clinical evidence that supports regular practice for

mental well-being. They discuss neurobiological mechanisms behind benefits, but

the review notes inconsistencies and methodological differences across

individual studies, which compromise the overall strength of the evidence.

Wu et al. (2016) proposed a convolutional neural network

(CNN) with transfer learning to recognize yoga poses automatically from images,

achieving high classification accuracy in controlled datasets. The study’s

limitation lies in its assumption of clear backgrounds and static postures,

which may not hold true in dynamic or real-world settings with occlusions or

complex environments.

Raghavendra

et al. (2019) explored the physical benefits of guided

yoga intervention by employing yoga pose recognition techniques to monitor

alignment improvements. The study also measured stress reduction outcomes,

confirming yoga's efficacy. Limitations include a relatively small sample size

and the use of predefined poses only, which could limit the applicability to

practitioners performing more advanced or hybrid postures.

Kishore

et al. (2022) conducted a comparative evaluation of four

deep learning architectures—EpipolarPose, OpenPose, PoseNet, and MediaPipe—for

yoga pose estimation. Using a database from the Swami Vivekananda Yoga

Anusandhana Samsthana (S-VYASA), they concluded that MediaPipe achieved the

highest accuracy in estimating five common postures. Their contribution

includes benchmarking model performance for yoga-specific data. However, the

training dataset covers only five asanas, which limits scalability to wider

yoga practice diversity. Additionally, the system mainly relied on monocular

input, which might not capture complex 3D posture nuances fully.

Shailesh

and Jose (2022) implemented a deep learning framework for

automatic yoga pose estimation and feedback generation. Their model integrates

pose estimation with feedback mechanisms to suggest corrections. They highlight

the utility of deep architectures in capturing intricate pose details. The

system was tested on a curated dataset but lacks validation in uncontrolled or

varied user environments. The challenge in generalizing model performance to

different camera settings and body types remains a concern.

Madhavi, M.,

Shashank, V., Vaishnavi, R., and Abhinav, S. (2024) proposed a convolutional

neural network (CNN)-based method for identification and correction of yoga

poses using an image database of five common asanas. Their approach focuses on

pose correction by detecting misalignments from captured images. The study

demonstrates promising pose classification accuracy, yet it is limited to

static images rather than continuous video streams, leaving temporal pose

consistency and dynamic movement unaddressed. This confines the practical

application in real-time yoga sessions where flow between poses matters.

Anusha

et al. (2025) developed a system using machine learning for

real-time yoga pose detection, leveraging the MediaPipe Blaze pose model

coupled with an XGBoost classifier. Their system extracts key body points,

classifies yoga poses, and provides real-time corrective feedback. This

approach is designed to improve self-practice accuracy and remote instruction.

While the model shows high accuracy, the study relies heavily on quality input

images and does not extensively address performance variability across diverse

user environments or lighting conditions, which may affect robustness in

real-world scenarios.

DATA COLLECTION

This part of the

study used still images of yoga postures taken before and after a one-month

period of practice. Images came from two sources: (a) photographs of study

participants who attended the yoga event, and (b) benchmark images collected

from public datasets and online resources used to define correct pose angles.

Images of the same participants were paired so that each person has a “before”

and an “after” image for the same pose; these paired images were used for

statistical comparison of landmarks.

IMAGES WERE OBTAINED FROM TWO PRIMARY SOURCES

Captured Images:

Photographs were taken under consistent lighting and background conditions to

minimize noise and ensure accurate detection of body landmarks. Each subject

performed selected yoga postures while standing at an optimal distance from the

camera to ensure full-body visibility.

Reference Images:

Benchmark images of standard yoga poses were collected from publicly available

datasets such as Kaggle, BLEED AI, and LearnOpenCV repositories. These

reference images served as the “ideal pose” models used to define standard

angle ranges and postural parameters for each yoga position.

The study focused

on Nine common yoga postures, including Virabhadrasana (Warrior Pose),

Vrikshasana (Tree Pose), Natarajasana (Lord of Dance Pose), Dandasana (Staff

Pose), Marjaryasana (Cat Pose), Bakasana (Crane Pose), Anjaneyasana (Crescent

Lunge), Buddha Konasana (Butterfly Pose), Naukasana (Boat Pose). For each

posture, a set of benchmark angle ranges was prepared to guide the

classification and evaluation process.

All personally

identifiable information was removed from the images. Each file was labeled

with an anonymous ID. All photographic data were used strictly for research

purposes in accordance with ethical research guidelines.

METHODOLOGY

The methodology

integrates image processing, Landmark Extraction, pose classification, 3D

landmark visualization, and statistical testing to objectively measure postural

improvement through yoga. The system was built in Python using OpenCV,

MediaPipe, and Matplotlib for visualization, and NumPy, Pandas, and SciPy for

mathematical computations.

IMAGE PROCESSING

To ensure

uniformity, all images were preprocessed before analysis using Python’s OpenCV

library. The preprocessing steps included:

·

Resizing:

Images were resized to a standard resolution suitable for MediaPipe processing.

·

Color

Conversion: Images were converted to the RGB color model for compatibility with

the pose detection model.

·

Noise

Reduction: Blurry or low-contrast images were removed.

·

Pose

Confidence Check: Each image was processed through the pose estimation model,

and only those with acceptable detection confidence scores were retained for

further analysis.

LANDMARK EXTRACTION

Each yoga image

was processed using MediaPipe’s Pose Estimation module, which automatically

detects and tracks key body points (landmarks). The model identifies 33

landmarks representing different joints and body parts. For this study, 12

specific landmarks were selected — focusing on joints most important for

posture symmetry and alignment, such as shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and

ankles. Using these landmark coordinates, joint angles were calculated using

the cosine law and Pythagoras theorem, allowing the program to evaluate whether

a pose matched the expected angle range of a known yoga posture. For each

image, the x, y, and z coordinates of these landmarks were extracted and stored

in a structured data file.

POSE CLASSIFICATION

Each image was

then automatically classified into a specific yoga pose by comparing the

calculated joint angles with pre-defined standard angle ranges derived from

reference images. If the angles of the test image fell within the acceptable

range of a known pose, it was labelled accordingly; otherwise, it was marked as

“unknown.” This rule-based approach achieved high accuracy and allowed

consistent recognition of different yoga postures.

3D VISUALIZATION OF POSTURE

After

classification, the 3D skeleton of each image was plotted using Matplotlib’s 3D

toolkit, where each landmark point was connected to show the entire body

posture. This visualization helped in understanding the alignment of the body

in three-dimensional space, which is crucial for evaluating balance and

symmetry.

SOFTWARE AND TOOLS

All computations

were carried out using Python 3.10 and R Studio with the following key

libraries:

·

OpenCV:

for image preprocessing and visualization.

·

MediaPipe:

for pose estimation and landmark extraction.

·

Matplotlib:

for 3D visualization of skeletons.

·

NumPy and

Pandas: for data storage and manipulation.

·

“Hotelling”

Package: for implementation of Hotelling’s T² test and statistical functions in

R Programming.

WORKFLOW SUMMARY

1)

Input

yoga image is captured or uploaded.

2)

Image is

pre-processed (resized, color-converted, and filtered).

3)

Pose

estimation is performed to extract 33 landmarks.

4)

Twelve

key landmarks are selected for analysis.

5)

Joint

angles and coordinates are computed.

6)

Pose is

classified based on defined angle ranges.

7)

3D

skeleton is visualized.

8)

Hotelling’s

T² test is applied to assess posture improvement.

RESULTS

This section

presents the outcomes of the computer vision model and the statistical

analysis. The system successfully identified various yoga poses from uploaded

images, generated 3D skeletal representations, and quantitatively evaluated

improvements in alignment using Hotelling’s T² test. The combination of visual

and statistical outputs provided both qualitative and quantitative evidence of

posture improvement after one month of yoga practice.

POSE RECOGNITION OUTPUT

Each input image

was passed through the trained image-processing model. The system detected the

human figure, extracted 33 landmarks, and matched the detected joint angles

with the standard angle ranges defined for each yoga pose.

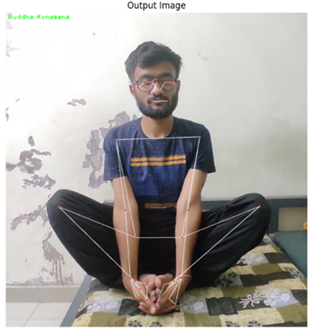

When an image of a

person performing Buddha Konasana (Butterfly Pose) was uploaded, the model

displayed the pose name “Buddha Konasana” on the output image along with a

bounding skeleton.

The model achieved

high visual accuracy in labelling other poses such as Vrikshasana,

Natarajasana, Dandasana, and Naukasana.

This visual output

confirmed that the pose recognition algorithm and landmark extraction process

were functioning correctly and could provide reliable data for subsequent

statistical analysis.

|

Figure 1 |

|

|

|

Figure 1 Original Image with Detected Pose

Name (Buddha Konasana) |

|

Figure 2 |

|

|

|

Figure 2 Corresponding 3D Skeleton

Visualization of the Same Pose |

VISUAL ANALYSIS AND 3D LANDMARK IMPROVEMENTS

The 3D skeletal

models generated for before and after practice sessions showed visible

alignment differences.

·

Before

practice: the 3D skeletons displayed slight asymmetry in shoulders and hips,

indicating imbalanced posture.

|

Figure 3 |

·

After

practice: the landmarks appeared more symmetrical, with straighter alignment

along the vertical axis.

|

Figure 4 |

MULTIVARIATE

TEST (HOTELLING'S T²)

The Hotelling’s T²

test was applied to determine whether the mean vector of body-landmark

coordinates showed a significant change after one month of yoga practice.

Hotelling’s T²

test is the multivariate extension of the paired t-test.

Number of

observations (image pairs): N=10.

Number of

variables (landmarks used in this test): p=6.

Landmarks (in the

order used): Left elbow, Right elbow, Right shoulder, Left shoulder, Left knee,

Right knee.

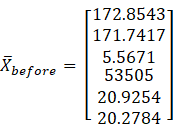

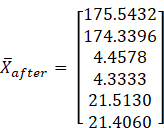

The sample mean

vectors (means of each landmark across 10 subjects) were:

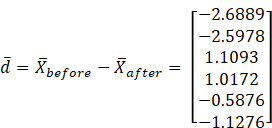

The vector of mean

differences used in the test (we will use d ̅=X ̅_before-X

̅_after) is:

(Notice sign:

negative means the after-value is larger than the before-value for that

coordinate.)

FORMULAE AND COMPUTATIONAL STEPS:

We followed the

Hotelling’s T² procedure for paired multivariate data (equivalent to the test

of symmetry of organs described in the methodology). The key steps and formulas

are:

Step 1 — Compute

the sample mean difference vector

Step 2 — Compute

the block covariance matrices and composite covariance

Let P_11be the

N×pdata matrix of “before” measurements (each row is a subject), and

P_22similarly for “after”. Define:

·

V_11

=Cov(P_11 ) (sample covariance of before),

·

V_22=Cov(P_22)(sample

covariance of after),

·

V_12=

sample cross-covariance between P_11and P_22(matrix of covariances between

before- and after- columns),

·

V_21=V_12^⊤.

Then form the

composite covariance matrix

![]()

Step 3 — Compute

Hotelling’s T² statistic for the paired test (symmetry form)

![]()

Step 4 — Convert

T² to the F-statistic

![]()

We then compute

the p-value from the F_(p,N-p)distribution and apply the usual significance

threshold (α=0.05).

Using the matrices

and vectors defined above, the computed values were:

·

![]()

·

Composite

covariance matrix S=V_11-V_12-V_21+V_22(used internally).

·

Hotelling’s

T² statistic:

![]()

·

Converted

F-statistic:

![]()

which follows

approximately F_(6," " 4)under H_0.

·

p-value

(from F_6,4):

![]()

Decision: since

p=0.0066<0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H_0(that the mean vector of

differences is zero). In plain words: there is a statistically significant

multivariate change in these landmarks after the intervention.

DISCUSSION

The present study

developed and applied an image-based analytical model to evaluate postural

improvements resulting from yoga practice. Using computer vision and pose

estimation algorithms, 3D skeletal landmarks were extracted from images of

participants performing specific yoga postures before and after a one-month

training period. The extracted landmark coordinates were analyzed statistically

using Hotelling’s T² test to detect significant multivariate changes in body

alignment.

The results

revealed that the test statistic exceeded the critical F-value, leading to

rejection of the null hypothesis. This confirms that the mean positions of the

selected body landmarks changed significantly after the yoga intervention.

Among the twelve original landmarks studied, six were analyzed in detail using

the symmetry test approach (elbows, shoulders, and knees). The largest

contributions to the multivariate difference were observed in the left and

right knees, followed by moderate differences in the shoulder regions. These

outcomes are consistent with the biomechanical effects of yoga, which emphasize

flexibility, balance, and muscular engagement in the lower body.

The integration of

computer vision with statistical inference offers an objective method to

evaluate human postural changes — something that traditional observational

assessment lacks. The 3D visualization of skeletal joints helped to clearly

illustrate the improvement in alignment and symmetry, validating yoga’s

physical benefits through quantifiable evidence. Furthermore, this approach

demonstrates that image-based pose analysis can be a reliable non-invasive

technique to measure progress in fitness and rehabilitation settings.

Despite these

encouraging findings, some limitations exist. The sample size of ten subjects

for the image-processing part was relatively small, and individual variation in

camera angle, lighting, or clothing might have affected landmark detection

accuracy. Additionally, the Hotelling’s T² test assumes multivariate normality,

which may not hold perfectly for small datasets. Future studies with larger

samples and multiple postures could help refine the statistical power and

generalizability of the model.

CONCLUSION

This study

successfully demonstrated that image processing combined with multivariate

statistical analysis can effectively measure the physical effects of yoga on

human posture. The developed Python-based model was capable of recognizing yoga

poses, generating corresponding 3D skeletons, and extracting precise joint

coordinates for further analysis. By applying Hotelling’s T² test to the

extracted landmark data, significant improvements were detected after one month

of yoga practice, especially in knee and shoulder symmetry.

These findings

confirm that consistent yoga practice leads to measurable physical improvements

in posture and alignment, and that computer vision can serve as a practical

analytical tool for tracking such progress. The work bridges traditional yoga

science with modern data analytics, offering a reproducible, data-driven

framework to evaluate human body dynamics.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1)

Expand

Dataset: Future research should include a larger number of participants and

multiple yoga postures to increase the robustness and generalizability of

results.

2)

Improve

Image Quality and Angles: Controlled image capture (uniform lighting,

consistent camera distance, and background) can enhance landmark detection

accuracy.

3)

Integrate

Real-Time Feedback: The pose recognition system can be extended to provide

real-time correction feedback during yoga practice using live camera input.

4)

Use

Advanced Models: Deep learning-based models such as OpenPose, BlazePose, or

MediaPipe Holistic can be incorporated for more precise landmark tracking and

3D visualization

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Anusha, N., Prabhu, S. S., and Poojari, S. S. (2025). Yoga Pose Detection. AIP Conference Proceedings, 3278(1), 020016. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0185767

Comprehensive Analysis of Pose Estimation and Machine Learning for Yoga. (2025). Procedia Computer Science.

Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., and Dobos, G. J. (2013). Yoga for Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 30(11), 1068–1083. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22166

Deeb, J., Morel, P., Ferrer, N., and Gurrutxaga, I. (2018). Real-Time Yoga Posture Recognition by Learning Key Human Pose Features. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2018, Article 435146.

Jain, S., Surange, S., and Jain, S. (2015). Yoga Pose Recognition Using Image Processing and Machine Learning. International Journal of Computer Applications, 117(6), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2015907083

Kishore, D. M., Bindu, S., and Manjunath, N. K. (2022). Estimation of Yoga Postures Using Machine Learning Techniques. Yoga Mimamsa, 54(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.4103/ym.ym_52_22

Li,

A. W., and Goldsmith, C. A. (2015). The Effects of Yoga on Anxiety and Stress. Alternative Medicine

Review, 17(1), 21–35.

Madhavi,

M., Shashank, V., Vaishnavi, R., and Abhinav, S. (2024). Identification and Correction of

Yoga Poses using CNN. International Journal for Research Trends and Innovation,

9(6), 268–276.

Mohan, C., Saini, A., and Vasudevan, S. (2020). Automated Yoga Posture Classification Using Transfer Learning from Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR).

Parkhi, O. M., Vedaldi, A., and Zisserman, A. (2015). Deep Face Recognition. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC). https://doi.org/10.5244/C.29.41

Pramanik,

T., et al. (2021).

A Study of Yoga Pose Estimation using Deep Learning. IEEE Access, 9,

140329–140344.

Raghavendra, S., Kanchan, K., and Rao, P. (2019). Effects of Guided Yoga Intervention on Body Alignment and Stress: A Yoga Pose Recognition Study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 46, 227–232.

Shailesh, J., and Jose, L. (2022). Yoga Pose Estimation and Feedback Generation Using Deep Learning. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, Article 4311350. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4311350

Wu,

P., Wang, L., and Zhang, Y. (2016). Automatic Recognition of Yoga Poses Using CNN and Transfer Learning.

Procedia Computer Science, 96, 313–321.

Wu, Y., Kiritchenko, Y., and Strohband, V. (2017). Facial Pose Estimation Using Convolutional Neural Networks.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2026. All Rights Reserved.