THE CHALLENGES OF MANAGING TAX

COMPLIANCE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: A CASE OF BOTSWANA

Jane M. Monyake 1![]() , Tshepo Maswabi 2, Kuruba

Gangappa 3

, Tshepo Maswabi 2, Kuruba

Gangappa 3

1 Department

of Management, University of Botswana, Botswana

2 Department

of Marketing, University of Botswana, Botswana

3 Former

Member at Department of Management, University of Botswana, Botswana

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Managing tax

compliance issues proved to be a complex administrative task for many

developing countries, especially in Africa. These challenges lie in

conceptual definition of tax compliance and noncompliance. Randlane

(2015) complains that the absence of universal definition for tax

compliance and tax noncompliance makes it difficult to differentiate

compliant behavior from non-compliant behavior. This paper explores tax

compliance management strategies which developing countries can learn from

and benchmark against. The study employs a content analysis method and taps

from scholarly journals and articles from different time periods, the most

recent being 2022. It adopts Randlane

(2015) Simplified

Model of Tax Compliance to investigate the

strategic approaches that simplify management of tax compliance and factors

that influence compliant decisions and choices. The framework provides some

helpful insights by distinguishing the three thronged strategic approach of

enforcement, service and trust, and the factors that must be closely

considered when developing tax compliance management strategies that might

help mitigate the major challenges confronting developing countries like

Botswana. The paper also explores

search words such as tax compliance, tax noncompliance, tax evasion, tax

avoidance, hut tax, and shadow economies. The paper concludes that no single

strategic approach effectively and sustainably manages tax compliance issues.

Further, that voluntary compliance remains an illusion Manhire

(2015) and Gildenhuys, 1997 cited in Botlhale

(2019) because compliance

has nothing to do with taxpayer willingness to pay or not to pay taxes as it

is an outcome that has already been achieved voluntarily or by force Randlane

(2015). |

|||

|

Received 12 October 2023 Accepted 13 November 2023 Published 29 November 2023 Corresponding Author Jane M.

Monyake, monyakeJ@ub.ac.bw DOI 10.29121/IJOEST.v7.i6.2023.551 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Tax Compliance, Tax Noncompliance, Compliance Strategies, Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance, Hut Tax, Shadow Economies |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Why Managing Tax Compliance is a Challenge to

Developing Countries?

It is indubitable that tax revenues notwithstanding the source significantly contribute towards government total revenues Botlhale (2019). These revenues are used to finance national capital and recurrent expenditures including but not restricted to development projects and social welfare, hence the importance of prudent management. Piolatto (2014) concurs that a country’s vital economic expansion is often achieved through robust tax collection initiatives. Ndlovu (2016) (citing Schneider, 2000) adds that governments’ inability to provide public services will not only undermine the efforts to increase people’s standards of living but will also slow down economic growth. Thus, ineffective strategic management of tax noncompliance makes it harder for governments to achieve these essential economic goals. Ndlovu (2016) citing Acemoglu et al, (2003) adds that countries with shadow economies suffer from tax evasion at individuals and enterprises due to lack the efficient tax collection methods. The author defines a shadow economy as an economy in which people do not show the real taxable income even income earned through legal activities Ndlovu (2016). Regarding Botswana, the authors unreservedly acknowledged and applauded the country for achieving economic growth through robust policies despite the numerous challenges she experienced. Thatshisiwe Ndlovu (citing Sedimo (1986)) adds that under shadow economies people use tax planning activities such as offshore tax havens and fraudulent accounting schemes (transfer pricing schemes) to minimize their obligations or evade tax. The author adds that this ‘status quo’ under shadow economies stems from countries inability to raise tax revenues enables them to provide the adequate essential public services to its people. Further, this behavior does not only undermine government intense efforts to generate sufficient public revenues but renders the varied tax compliance initiatives ineffective Ndlovu (2016). Citing Botlhale (2016) Ndlovu observes that taxpayers do not only make use of acceptable tax avoidance strategies but also employ fake techniques with the support of tax officials to reduce or evade or avoid their taxes. He calls tax evasion and tax avoidance two evil spirits which do not only generate the gap between probable and actual government revenues, but also reduces government’s potential to finance public services and social welfare of its people and negatively impact on the country’s global perception ratings on good compliance and heightens corruption levels Ndlovu (2016). Thus, it necessitates enforcement of stringent tax laws and strategies such as penalty charges and periodic audit of tax returns people Botlhale (2019).

Most of the scholarly journals and articles reviewed focused on the history of tax evasion and tax avoidance, determinants of tax compliance, and evaluating the factors that influence tax noncompliance and comparative analysis of tax administration at global and continental perspective, Botswana included. Thus, the paper seeks to draw lessons from countries worldwide that have successfully developed simple and yet effective tax compliance management strategies from which developing countries like Botswana which are still struggling in tax administration can benchmark against.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

This section explores global perspectives on the challenges of managing tax compliance and the impact of noncompliance on the developing and emerging economies. Furthermore, it considers the pragmatic tax management strategies explored by different scholars with view to identifying the best strategies that can effectively help address tax compliance challenges in developing countries especially in African countries like Botswana.

3. CONCEPTUALISATION OF TAX COMPLIANCE

There is no universal definition for tax compliance Tilahun (2019), Randlane (2015), different scholars define the concept in different ways. For instance, Aladejebi (2018). defines tax compliance as obedience of tax laws with view to balancing off the economy, but to Song & Yarbrough, 1978 (cited in Palil & Mustapha (2011)) tax compliance is a voluntary act which demonstrate the taxpayer’s ability and willingness to comply with tax laws. Singh, 2003 cited in Palil & Mustapha (2011) asserts that tax compliance indicates the taxpayer’s willingness to fulfil tax obligations by declaring correct taxable incomes and timely payment of outstanding taxes. Citing a US tax system scenario, Manhire (2015) affirms that 97% of the tax revenues collections in US came from voluntary compliance (e.g., self-assessments) and 3% from enforced compliance through vigorous returns audits and tax penalties. He however disputes the issue of the taxpayer voluntary compliance arguing that most taxpayers do not believe they have a choice when it comes to filing tax returns and paying taxes. He thus proposes that the concept of ‘voluntary compliance’ should be changed to ‘cooperative compliance’ to minimize taxpayers ‘confusion. He cautions that the term ‘cooperative compliance’ should be properly handled to avoid or minimize taxpayers’ negative perceptions (e.g., harassment through periodic audits) by tax authorities. The author calls for proper management of enforced civil tax penalties strategy to effectively close the tax gap created and widened by the underpayment of the actual tax amount. He argues that such step would help prevent exacerbating the problem of noncompliance and encourage compliance Manhire (2015). Gildenhuys, 1997b (cited by Botlhale (2019)) endorses Manhire’s view on contradictions and confusions that are likely to be caused by using the term, voluntary compliance’. He opines that taxes are involuntary contributions to governments that do not entail direct quid pro quo (agreement), as such they cannot be presumed to be voluntary.

Randlane

(2015) concurs that it is

meaningless to align tax compliance to willingness to pay taxes because the

term ‘compliance’ is an outcome that has already been achieved either

voluntarily or through interventions. He suggests that willingness be replaced

with trust, arguing that without a trusting relationship between tax

administrator and taxpayer, neither enforcement through tax audits and tax

penalties nor providing good service alone will not achieve the desired tax

compliance objective. Tilahun

(2019) agrees with Randlane

that voluntary and enforcement strategies alone will not successfully curb the

problem of noncompliance. However, he

objects Randlane proposition of building a trusting relationship between the

tax authority and taxpayer, and the carrot and stick approach which advocates

taxpayer’s economic rationalization of income and wealth maximization. Instead,

he recommends a responsible citizen’s approach where governments seriously

consider factors like social support, social influence, attitudes, age, gender,

racial and cultural issues to improve tax reform framework Tilahun

(2019).

4. CONCEPTUALISATION OF TAX NONCOMPLIANCE

For this paper, tax noncompliance is linked to tax avoidance and tax evasion. This definition is consistent with Coetzee (1993) cited in Ramfol (2019) definition which links tax evasion to a deliberate refusal of a taxpayer to disclose one’s sources of income to the tax authority with the intention of paying nothing or something less in terms of one’s tax liability is an attempt to evade tax. Walt (2012) calls tax evasion and tax avoidance the major tribulations plaguing many different economies across the world which disable them to adequately cater for their socio-economic needs. The author cites self-employed like businessmen, contactors and professional practitioners like lawyers and doctors as probable tax evaders who are likely to reporting losses every year. Schapera 1970 and Acemoglu (2003) (cited by Ndlovu (2016))suggests that tax evasion twists the business morals and ethics as people try to look for loopholes in the tax system to manipulate it. He adds that tax avoidance on the other hand causes investment distortions whereby companies and individuals undervalue their goods or have some assets being exempted from tax. To Ariffin etal (2018) tax avoidance is a crime which does not only result in inequality of income distribution but widens the tax gap as it involves underreporting the actual tax amount; actions which Nkwe (2013) (cited by Aladejebi (2018) asserts lead to economic instability due to slow or no economic growth. Kim (2015) cited by Palil & Mustapha (2011) adds that such behavioral actions make it difficult for governments to achieve the objectives of developing the country and growing the economy.

Noncompliance decisions are influenced by numerous factors

including but not limited to social and psychological factors social and

psychological factors Tilahun

(2019), Palil

& Mustapha (2011). Manhire (2015) suggests that factors such as

ignorance, human passion, a

rational fear of adverse consequences and physical force should be greatly

considered as they can negatively impact taxpayers’ decisions to be compliant

by reducing their level of voluntariness. Aladejebi

(2018) adds that

factors like the level of trust in government, tax rates and interest on

default and compliance costs. Citing Nkwe

(2013), the author adds

that complicated filing procedure and tax knowledge under self-assessment

system should also be given adequate attention because they influence

noncompliant behaviour.

Warner (2015) asserts that corporate tax offenders often design innovative tax shelters to reduce and obscure the true tax liabilities of their individual shareholders. These are created by combining multiple business structures like partnerships, trusts, and S-corporations into complex transaction networks. It is against this backdrop that Adebisi & Gbegi (2013) cited by Aladejebi (2018) suggest investigation of different motivations and cultural factors like religiosity, trust in the government and legal enforcement when investigating tax evasion and avoidance cases. Typical example in Botswana are the frequent introduction and revision of numerous tax levies on almost every service that is provided by state owned enterprises such as Water Utilities Corporation, Botswana Power Corporation, city and district councils for waste management and other services, etc. These frequent revision of tax laws have not only created unnecessary confusion for new taxpayers but have also exacerbated the existing tax management complexities confronting Botswana Unified Revenue Services (BURS). The other example relates to the numerous complaints against the tax authority staff for refusing to assist taxpayers to complete the tax form despite the complexity of the forms prior to the introduction of e-tax filing.

This behavior exhibited by tax authority staff is consistent with Alm & MCClellan (2012) assertion that taxpayers’ attitudes may be influenced by taxpayers’ deposition towards public institutions besides the perceived fairness of the taxes, prevailing social norms and chances of non-compliance being detected and punished. This calls for tax administrators to reflect on their own behavioral attitudes and try to understand taxpayers’ reluctance to appreciate fulfilling their tax obligations by way of filing of tax returns and payment of correct tax amounts due on time. Randlane (2015) (citing Kirchler 2017 & Kirchler Hoelzl, & Wahl, 2008) recommend that tax administrators should periodically introspect with view to ensure that they conduct themselves with a high sense of justice and fair play, honest and above suspicion, and that administration activities are conducted in a transparent manner. Tilahun (2019) and Fjeldstad 2012 cited in Ariffin et al, (2016) suggest closer attention to moral and psychological factors before accusing taxpayers of tax avoidance or evasion crimes.

Stiglingh et al. (2022) emphasizes the need to define the behavior that constitutes tax evasion from that which influences taxpayers’ desire to avoid tax when addressing the issues of noncompliance because the two concepts have different meanings to different people. The authors add that the taxpayer is not obligated to pay a greater amount of tax than is legally due under the Income Tax Act if she/he had arranged his or her affairs in a perfect legal manner. Meaning that the taxpayer cannot pay anything outside his/her tax bracket, and thus it will be senseless to indict her/him for failing to observe tax laws because no offence has been committed Stiglingh et al. (2022). Axinn & Pearce (2016) suggests that tax authorities should firstly establish if taxpayers’ actions were (i) deliberately undertaken to cheat the system (e.g., free themselves from the tax burden by omitting additional income from annual tax return), which amounts to tax evasion. (ii) less intentional whereby the taxpayer has arranged his or her affairs in a perfect legal manner with the result that he/ she has either reduced the taxable income or has no income on which tax is payable, which amounts to tax avoidance.

5. THE CHALLENGES OF TAX COMPLIANCE/NON-COMPLIANCE IN BOTSWANA

The concept of tax evasion and avoidance is not totally new in Botswana. According to Makgala, 2004 cited by Ndlovu (2016) tax noncompliance dates to the crude system of hut tax during Bechuanaland Protectorate era in 1899 where tax revenues were collected through the chiefs in the form of cash, grain and livestock from natives who occupied huts to cover the High Commissioner administrative costs. Makgala asserts that people devised innovative ways to evade or avoid the burden of the hut tax by staying in trunks of baobab trees or shared huts. Botlhale, 2016 cited by Ndlovu (2016) complains that these practices do not only discourage some honest individuals who fulfill their tax liabilities but also create fertile ground for tax evasion for future or prospective employers and employees. He argues that despite governments’ efforts to reduce incidents of tax evasion, some corporations and people still willfully deploy ‘fake/creative accounting techniques and tax avoidance strategies to reduce the flow of tax revenues into government coffers. Botlhale 2016 cited in Ndlovu (2016) and Pashev (2015) assert that tax evasion is now most rampant among the professionals, arguing that the lifestyles of these people are inconsistent with their reported unrealistic low income for the nature of their businesses and/or job positions.

Botlhale adds that lack of sufficiently knowledgeable and experienced staff at BURS exacerbates the noncompliance problems Ndlovu (2016). The lead author of this paper concurs with Botlhale’s assertions that shortage of adequately trained coupled with inexperienced personnel and the inefficient organizations procedures aggravate the tax administration challenges in Botswana. Her tax returns for 2015 and 2019 despite having been filed with BURS within the relevant tax periods were assessed in 2021 and 2022. Her observations are also consistent with the findings of the empirical study undertaken by Peprah et al. (2020) in Ghana, whose findings revealed low institutional capacity, inadequate resources, negative public attitude towards tax payment, lack of collaboration between the tax agencies, and political interference as tax administration related challenges, and a lack of tax education, high tax rate, low level of income, and high household consumption levels as the predominant influential factors to tax noncompliance.

Citing public uproar against tax administrators in South African, Ramfol (2019) asserts that the problem of tax evasion is exacerbated by tax administrators’ maladministration which he alleges is affirmed by people’s dissatisfaction and concerns over the management of the public’s funds. Contrary to Ramfol’s assertion, Warner (2015) blames inadequate funding for training programs to upskill the tax administrators, and too much leniency in imposing penalties on tax evaders as the key factors that contribute to noncompliance. Tax evasion indulgence was also observed by researchers from foreign owned textile enterprises located in the northern part of Botswana, who were recipients of Financial Assistance Policy (FAP) during 1990s. These firms continually declared operating losses despite the numerous monetary subsidies they received through FAP. A similar practice is presently observed from the firms that sell their products and services for cash only, and from foreign owned firms which use ordinary citizens to front for them especially those that engages in money laundering activities like auto mobile firms in Mogoditshane, Botswana Selatlhwa (2018). The landlords of multi residential properties in Tlokweng and Mogoditshane are also reported as typical examples of elusive tax evaders Mmegi Online-Pauline Dikaelo (2020). Seitshiro (2022) laments that it is unfortunate and highly unlikely that tax evaders can be prosecuted in Botswana because of alleged corrupt tax administrators who help these villains to evade tax in exchange for bribes.

6. TAX NONCOMPLIANCE RELATED CHALLENGES

There is no country in the world which does not experience noncompliance problems. Tilahun (2019) opines that taxpayers’ willingness to oblige by tax laws reflects individual taxpayers’ deliberate decision and attitude toward paying taxes, conceptions, and norms, as well as their intrinsic motivation to pay taxes. Nkwe (2013) cited in Aladejebi (2018) adds that taxpayer’s attitude whether positive or negative reflects an essential component of tax compliance. Palil & Mustapha (2011) adds cost-benefit implications to the list of factors that influence noncompliance. The authors posit that people compare costs and benefits of any activity that they engage on, and the potential benefits and risks of their social relationships. For example, some taxpayers are very good at underreporting receipts, overreporting expenses, misreporting the actual income earned, deductions and credits White (2012), while some manipulate their financial records by altering their financial statements to reduce their tax liability (GAO, 2012). There is consensus that tax is not only evaded or avoided by ordinary taxpayers and small firms but also by affluent people and large firms. In their study, Alstadsæter et al. (2022) affirm that the affluent people evade tax through the high-profile leaks from offshore financial institutions whilst the poor people evade tax through self-employment schemes and abuse of refundable tax credits. Further that high mobility of employees (e.g. those without permanent place of residence) and self-employed like hawkers may be used as weaponry to evade tax because while these individuals reside and work everywhere, they earn legal incomes which if they were declared would attract tax.

7. GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON ECONOMIC EFFECTS OF TAX NONCOMPLIANCE

Tax noncompliance is blamed for constraining government investments, be it recurrent or capital expenditures. Gale & Samwick (2014) agree that tax noncompliance puts a halt to planned economic growth and development. Further that it generates investment distortion in the form of the purchase of assets exempted from tax or undervalued for tax purposes Onyeka & Nwankwo (2016) citing Kiabel & Nwokah 2009). Hamel (2015) (cited in Morse (2015) adds that the absence of funds in any country naturally prevents governments from carrying out their responsibilities for the benefits of the people and from undertaking international investments that will boost their economies. Aladejebi (2018) concurs that tax noncompliance influences public expenditure and capital accumulation, which in turn affects output and economic growth. The author complains that as this behavior sets in, it becomes difficult for governments to achieve the basic amenities such as the creation of good roads, provision of water, building of public schools, maintenance of facilities, payment of salaries of civil servants etc. Tanzi (2017) agrees that inadequate public funds hamper social welfare and economic development and forces governments to borrow or utilize their foreign reserves. Fjeldstad (2012) cited in Ayuba et al. (2016) adds that the situation is exacerbated by companies that declare higher dividends for their shareholders and underreport the actual profits generated, and individuals with high take home income who underreport actual income earned. It is therefore imperative that all such activities are discouraged or prevented at all costs.

Alabi (2001) cited by Onyeka & Nwankwo (2016). posits that despite the government efforts to curb the practices of tax leakages in Nigeria, the problem of tax noncompliance continues to increase. The persistent noncompliant behavior in Nigeria is linked to exorbitant import tax and value added taxes. Nkwe, 2013 cited in Aladejebi (2018). complains that recurring noncompliant behaviors do not only erode moral values but also build up inflationary pressures because of the imbalances created by the forces of demand and supply. Further that such behaviors generate investment distortion in the form of the undervalued purchase of assets exempted from tax. It creates inequality and injustice among taxpayers, in such a way that honest taxpayers continue to pay their taxes because they feel obligated whereas dishonest taxpayers prefer to evade and avoid paying tax. Tilahun (2019) concurs that perceived fairness of tax laws directly influence noncompliance behavior citing that the taxpayer’s compliance will decline if they perceive that they are paying higher than other taxpayers earning the same income.

8. IMPACT OF TAX NONCOMPLIANCE ON BOTSWANA’S ECONOMY

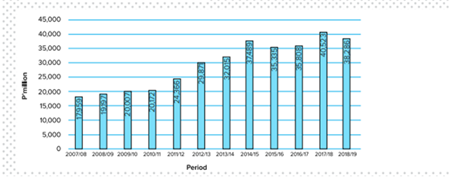

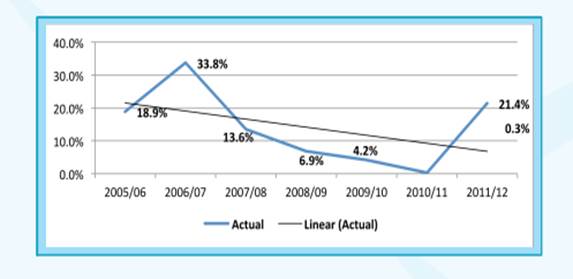

The impact of tax noncompliance in Botswana economy is measured by the collection efforts, tax revenue growth rate and percentage contribution to GDP as reflected in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 below. Figure 1 provides a glimpse into the government tax collection efforts between the periods 2008 and 2019 and Figure 2 depicts the percentage contribution of taxes to GDP between the periods 2005/06 and 2016/17, whilst Figure 3 shows tax revenue growth rates between 2005 and 2012.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Yearly Total Tax

Revenue Collection in Pula Millions 2007/08 - 2018/2019 Source BURS

Annual Report, 2019 |

Figure 1 shows annual total tax collections between 2007/08 and 2018/19 ranged from the lowest of P17, 959 million in 2007/08 to the highest of P40, 523 million in 2017/18. The low collections were reported at approximately P35, 335 million in 2015/16, P35, 808 million in 2016/17 and P38, 286 million in 2018/19 respectively (BURS Annual Report, 2019). The fluctuations in tax collections between 2014/15 and 2018/19 may be attributable to possible tax evasion resulting from weak tax administration and high tax rate as they happened before the Covid19 pandemic inundated nations and ravaged economies. However, notwithstanding the significantly low tax revenues in 2018/19, Finance Minister Kenneth Matambo 2018/19 Budget Speech estimated total tax revenues and grants at P60.20 billion (US$5.44 billion) and customs excise revenues at P14.02 billion (US$1.27 billion) for the fiscal year 2019/20 Botlhale (2019). However, despite the growing fears of persistent erosion of tax revenues resulting from noncompliant behavior, Whalen (2020) reports that the issue of tax noncompliance was not unique to Botswana as on average governments across the globe lose US$427 billion. Africa loses about US$25 billion (7 percent of the continent’s average tax revenues) each year, Europe US$ 184 billion, Asia US$73 billion, and US US$90 billion each year respectively.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Showing Percentage Contribution of Taxes to GDP From 2005-2017 Source BURS Annual

Report, 2017 |

The tax percentage contributions as per Figure 2 above show the lowest of 20.9% in 2010/2011 and the highest of 26.5% in 2012/13 respectfully. The declining trend beyond 2013 is consistent with the percentage tax contribution to GDP which even at the highest of 26.5% remained below the international standard of 30% Marshal, 2014 cited in Hoxhaj & Kamolli (2022). However, the 20.9% GDP contribution in 2010/11 may not be wholly attributable to tax noncompliance but also to maladministration and corrupt practices from BURS Seitshiro (2022). On another note, the low GDP tax contributions may reflect heavy reliance on mineral resources and tourism activities during these fiscal years.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Tax Revenue Growth Rates in Botswana: 2005/06 To

2011/12 Source BURS

Annual Report, 2012 |

Figure 3 above shows that BURS only enjoyed significant tax revenue growth rate in periods 2006/07 and 2011/12 at 33% and 21.4% respectively. The institution experienced significant decline in revenue growth rate between the periods 2007/08 at 13.6%, 2008/09 at 6.9, 2009/10 at 4.2% and 2010/11 at zero growth rate. The zero-tax revenue growth rate is consistent with the GDP percentage tax contribution for the same period and this diminishing growth rate may indicate probable tax evasion. These performance reports may be linked to tax leakage caused by several system loopholes such as exorbitant tax rates and underreporting of assets and income Nightingale, 1997 cited in Aladejebi (2018). Saidu & Dauda (2014) assert that taxpayers’ indulgence in tax evasion may be encouraged by the non-transparent attitude of tax professionals who are expected to promote transparency of the practices and detect fraud.

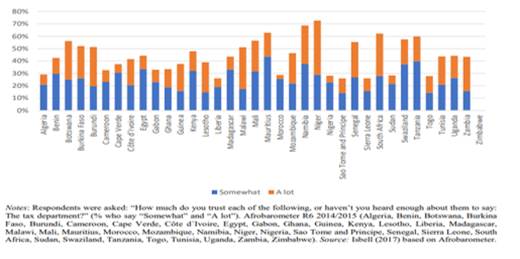

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Trust in the Tax Department (% Of Respondents) in Africa Sources Custers, Dom, Davenport

& Roscitt (2019 citing Isbell (2017) |

A comparative analysis study undertaken by Cummings, Martinez-Vazques, Mckee and Torgler (2006) cited

in Ramfol

(2019) between South African and Botswana which measured taxpayers

‘perception of tax administration system reveals that Batswana unlike their

South African counterpart perceived paying taxes as part of the social contract

and as a price paid for government services. These findings show high levels of

citizen’s respect for the state and institutions that govern economic and

social interventions, level of political stability, absence of violence, level

of institutional quality in Botswana compared to South Africa. They are

consistent with the 2014/15

Afrobarometer ratings of approximately 55% for Botswana Tax Department (Figure 4 above).

9. STRATEGIC MEASURES TO COMBAT NONCOMPLIANCE TAX

Most countries, especially emerging economies, are still struggling to develop strategic management approaches that can effectively and sustainably manage tax noncompliance challenges. Fjildstad (2012) posits that closing all loopholes in the law and introducing new tax legislation can help discourage tax noncompliance. Najera (2011) propose several strategic approaches that can help detect tax offenders and discourage noncompliance. These include creating new international policies with tax haven nations, increasing statute limitations, and stepping up tax collection enforcement. Palil & Mustapha (2011) and Whalen (2020) agree that (i) increased tax returns audits and penalty rates, (ii) building good relationships with taxpayers, (iii) stricter enforcement of filing, and (iv) introducing and implementing good tax management system, stronger international policy, exchange of information, solid tax laws, and tax education may discourage noncompliant behaviour. Cobham (2022) on the other hand, suggests complete overhaul of global tax laws with a view to (i) stopping companies from shifting profits to low-tax havens, (ii) exposing the size and provenance of the huge private fortunes held offshore, and (iii) protecting every country’s right to collect tax from the profit generated within its borders.

Alm et al. (2010) suggest strategies such as reduction of tax rates, minimizing controls in the economy, getting public opinions, and regulating donations to encourage compliance. Green (2019) believes that strategic approaches such as (i) simplifying the tax code, (ii) making clearer the distinction between lawful and unlawful behavior (iii) making a clear distinction between what constitute criminal and civil violations of the code, (iv) changing political rhetoric, (v) educating people about the importance of tax revenues, and (vi) modifying priorities for government spending might help encourage compliant behavior. Malkawi & Haloush (2008) recommend investigation of countries that do not report foreign investments. These authors however caution that whilst this action may be worthwhile, it can be costly because of the unnecessary extra time that would be spent in getting countries to cooperate with the investigations, and substantial expenditure would be incurred pursuing and prosecuting these tax offenders. Eboziegbe (2007). concurs that it is probable that the benefits of prosecution may be less than these costs. Mann (2006) suggests various ways in which tax compliance may be achieved. These include (i) rewarding compliance, limiting changes to the tax code, (ii) providing meaningful customer service, (iii) publicizing IRS provided services, (iv) simplifying tax code, (v) selectively publicising enforcement, (vi) discouraging tax evasion and tax avoidance, (vii) considering alternatives to the label “tax”, (viii) showing what taxpayer money purchase and (ix) providing a simple return process for most taxpayers.

It is worth noting that whilst these strategies may prove effective remedies for encouraging tax compliance in some countries, they may be less effective and less sustainable in others due to inadequate resources (budgetary constraints) to implement them David & David (2016). Furthermore, there is no guarantee that tax noncompliance will immediately stop upon their implementation because of the individual taxpayer’s behavioural attitudes, choices and/or decision to pay or not pay the tax.

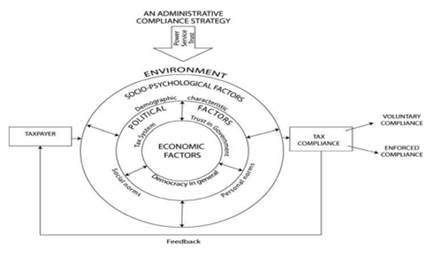

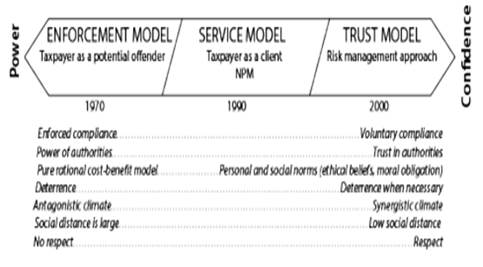

10. RANDLANE (2015) TAX COMPLIANCE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Randlane (2015) Conceptual Framework (A Simplified Model of Tax Compliance as a System) depicted in Figure 5 below illustrates the complexities involved in management of tax compliance. The model shows a three-throng strategic approaches of enforcement (power), service provision and trust relationships between the tax administrator and the taxpayer which greatly influence the tax administrative compliance strategy. The model shows that tax compliance can be voluntary and enforced. Further, the compliant behavior is determined by diverse environmental factors which are encapsulated in Figure 6 and Figure 7 below.

The Enforcement Model/Economics of Crime Approach” Randlane (2015), citing Beker, 1968 was commonly used during 1970s (refer to Figure 6 below). This approach presumes that all taxpayers have one thing in common, which is to betray and steal from the state by devising manipulative ways to evade or avoid tax, and that such behavior deserves tough punishment to discourage dishonesty. It considers taxpayers as potential criminals whose aim is to cheat the state by evading or avoiding tax. The model aligns very well with Kirchler (2017) assertion that taxpayers’ decisions to evade tax are motivated by greed and desire to maximize personal benefits. It embraces enforcement of punitive measures in the same fashion as all other law enforcement agencies. The authors of this paper call this model “Abusive Model” because it signifies abuse of power by tax authorities with the aim of degrading taxpayers. From this model it is very clear that taxpayers’ decisions to comply with tax laws and regulations may not be voluntary all the time Manhire (2015). For example, compliance may be obtained through law enforcement whereby the administrator undertakes periodic tax audits and sanction penalties for noncompliance. There are, however, instances whereby the taxpayer will demonstrate his/her good citizenship through voluntary compliance. This, however, will depend on several factors including the relationship between the taxpayer and the tax administrator. For example, the extent to which the taxpayer perceived the fairness of the service provided and the degree of trust level between these parties. The Enforcement/Power Model

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 A Simplified Model of Tax Compliance as a System Source Kerly Randlane (2015) |

The second model is the “Service Model” which was used during 1990s. Under this approach, the tax authority assumes the role of service provider and treats the taxpayer as a customer. The model aims at reducing hostility between the tax authorities and the taxpayer and encouraging and /or enhancing compliance through provision of quality service to taxpayers. The authors of this paper call this model “make believe” as it is meant to flatter the taxpayer into believing that he/she will receive the quality service, which is not always the case. The third approach is the “Trust Model”, is the most current. According to Randlane (2015), this model seeks to establish “why people pay tax”. The approach is premised on a win-win situation, and it aims at promoting and developing a healthy relationship of trust between the tax authorities and the taxpayer as well as boosting the taxpayer’s self-esteem. Trust models align to voluntary compliance as it is based on perceived fairness and transparency of the tax system and the conducive environment that allows taxpayers to freely participate in the tax reforms or enactment of new tax laws Ramfol (2019) and Bani-Khalid et al. (2022) citing Alshirah et al. (2019). The model is also consistent with Cummings, Martinez-Vazques, Mckee & Torgler (2006) cited in Ramfol (2016) assertion that taxpayer becomes compliant when government is trustworthy, tax enforcement mechanisms are perceived as fair, and the fiscal exchange is deemed beneficial to taxpayers. The authors of this paper call this model “Respect Model” because the tax authorities recognize the taxpayers’ individuality as trustworthy human beings capable of behaving rationally without force.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Interaction Climates Between Taxpayers and Tax Authorities Source Kerly Randlane (2015) |

Randlane’s economic factors are expanded diagrammatically

in Figure 7 below. They are linked

to the traditional thinking that coercive interventions (power approach) are

ideal solutions for ensuring compliance with tax laws. The approach also recognises the importance of

environmental factors such as social norms and morals, and taxpayers’ attitudes

and perceived social pressures embraced in Bobek

& Hatfield (2003) and Alshirah et al. (2019) cited in Bani-Khalid et al. (2022). The authors (citing Etzioni, 1986)

add the cultural differences influence, the perceived fairness and transparency

of the tax system and fiscal exchange to the important factors that promote

taxpayer’s compliance

Randlane (2015) and literature reviewed reveal that tax compliance is shaped by both economic and noneconomic factors as captured in Figure 7 below. These include instances when (i) people embrace the public good voted on rather than imposed; (ii) the political outcome is known Alshirah et al. (2019), (iii) tax compliance requirements are friendlier Aladejebi (2018), and when trust in government and taxpayers’ morale is high and there is perceive fairness of the tax system and delivery of government services Ramfol (2019).

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Main Determinants of Compliance Behavior Source Kerly Randlane (2015) |

11. DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

1) Which

Factors Greatly Influence Noncompliance Behavior of Taxpayers?

From the literature reviewed, it is evident that the issues of tax noncompliance will continue to haunt several countries across the globe for as long as the tax revenues contributes significantly to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). There is no doubt that tax compliance has direct implications on tax generated revenues. For instance, the high level of compliance will result in high tax revenues and low compliance levels will reduce the tax revenues. The degree of compliance on the other hand is influenced by diverse factors as encapsulated in Randlane (2015) Conceptual Framework. These factors include (i) the absence of effective sustainable tax compliance framework Tilahun (2019), Randlane (2015), (ii) lack of a universally accepted definitions of the concepts of tax compliance and tax noncompliance Stiglingh et al. (2022) and (iii) clear distinction between voluntary or involuntary compliance (Gildenhuys, 1997 cited in Botlhale (2019), Manhire (2015). There is no doubt that Randlane (2015) tax compliance approach is consistent with several scholarly work that emphasized the importance of investigating the non-economic factors like ignorance, human passion, a rational fear of adverse consequences and physical force Manhire (2015). Bani-Khalid et al. (2022) blame noncompliant behavior on instability created by frequent amendment of tax laws and its effect on the taxpayer’s appreciation of, and adherence to the new additional provisions on tax laws. Aladejebi (2018) citing Adebisi & Gbegi (2013) asserts that noncompliant behavior may be influenced by cultural factors like religiosity, trust in the government besides legal enforcements. He adds that level of trust in government, tax rates and interest on default, complicated filing procedure and tax knowledge under self-assessment system should also be adequate considered when developing compliance tax strategic management approach Aladejebi (2018). Alm & MCClellan (2012) concur that a shift from economic factors to factors like taxpayers’ deposition towards public institution, perceived fairness of the taxes, prevailing social norms, and chances of being detected, caught, and punished will minimize the challenges experienced in managing tax compliance issues effectively.

2) Which

Management Approach Will Successfully Mitigate the Challenges of Noncompliance:

Voluntary Vs Enforcement?

Tilahun

(2019) opines that neither

voluntary nor enforcement strategies alone will not successfully curb the

problem of noncompliance. The author suggests that any strategic approach

devised to minimize tax noncompliance should start with a theory of why

taxpayers evade tax. Further that such

an approach should follow a responsible citizen’s approach in which governments

seriously examine the reasons for non-compliant behavior. The study should

consider factors like social support, social influence, attitudes, age, gender,

racial and cultural issues targeted to improve tax management reform framework

as opposed to the carrot and stick approach which advocates taxpayers’ economic

rationalization of income and wealth maximization. Hofmeyer

(2013) recommends

investigation of the different motivations for reluctance or minimal compliance

requirements to pay taxes or abide with tax laws. Randlane

(2015) attempted to

do exactly that through his conceptual tax compliance management framework.

After a thorough analysis of all the factors that are presumed to influence tax

compliance, the author concluded that depending on a single strategic approach

(be it enforcement or treating taxpayer as a customer or creating a trusting

relationship with taxpayer or providing service to taxpayers) to handle tax

compliance issues will not yield good results.

For instance, implementing enforcement interventions via periodic audits

and/or sanctioning penalties for noncompliance will not deter defaulting

taxpayers from avoiding or evading tax. Instead, these measures may motivate

tax defaulters to search for more innovative mechanisms to evade tax. He adds

that provision of quality service by tax administrator alone will not discourage tax noncompliance

because compliance is not willingness to pay taxes but an outcome that

has already been achieved either voluntarily or through interventions.

12. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From the analysis above, there is a consensus that no single strategic approach can effectively and sustainably manage tax compliance issues. Further that voluntary compliance is just an illusion (Gildenhuys, 1997 cited in Botlhale (2019)) and Manhire (2015) because compliance has nothing to do with taxpayer willingness to pay or not to pay taxes as it is an outcome that has already been achieved voluntarily or by force Randlane (2015). A universally accepted conceptual definition and the legal distinction between compliant and noncompliant behavior might help to effectively address the tax compliance and tax noncompliance issues. Further motivations for noncompliant behavior need to be explicitly explored when investigating the factors that influence tax policies and administration strategies. Tax authorities should constantly review and revise their tax policies and regulations in line with socio-political and economic trends with a view to enhancing their effectiveness and sustainability.

Developing countries, like Botswana should strive to ensure its tax legislature aligns to (CIAT, 1996 & OECD, 1999 – cited in Botlhale (2019)) requirements that insist that member countries should win taxpayer trust and ensure tax administration that guarantee integrity and impartiality. They should consider measures like simplifying tax policies/tax code, reducing tax rates and strengthening tax administrators through training, providing high quality services to taxpayers, encourage whistleblowing and modernisation of information systems Mann (2006). The tax authorities should also intensify taxpayer and tax administrators’ education and improve public campaigns via digital media, distribution of brochures and pamphlets, door to door campaigns, road shows, etc. Warner (2015) suggests innovative tax shelters such as combining multiple business structures like partnerships, trusts, and s-corporations into complex transaction networks to reduce and obscure the true tax liabilities of their individual shareholders. Whalen recommends stricter enforcement of filing, good tax management system, stronger international policy, exchange of information, solid tax laws, increased tax audits, tax education or other means that would enable government to generate funds needed for funding the country’s socio-economic activities Whalen (2020).

All these strategic efforts are not expected to minimise taxpayers’ complaints and perceptions towards tax administrators attitudes and fairness of the taxes, prevailing social norms and chances of non-compliance being detected and punished Alm & MCClellan (2012) but also to refine tax framework. They should continually learn and benchmark against other countries best practices and adopt Randlane (2015) Simplified Model of Tax Compliance.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aladejebi, O. (2018). Measuring Tax Compliance Among Small and Medium Enterprises in Nigeria. International Journal of Accounting and Taxation. 6(2), 29-40. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijat.v6n2a4.

Alm, J., & MCClellan, C. (2012). Tax Morale and Tax Compliance from the Firms' Perspective. KYKLOS, 65, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2011.00524.x.

Alm, J., Martinez-Vazquez, I., & Torgler, B. (2010). Developing Alternative Frameworks for Explaining Tax Compliance. eBook ISBN9780203851616. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203851616.

Alshirah, A. F., Abdul-Jabbar, H., & Samsudin, R. S. (2019). The Effect of Tax Moral on Sales Tax Compliance Among Jordanian Smes, International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, (Print ISSN: 2308-0337; Online ISSN: 2225-8329). 9(1), 30-41. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v9-i1/5722.

Alstadsæter, Annette & Johannesen, Niels & Le Guern Herry, Ségal & Zucman, Gabriel (2022). "Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance," Journal of Public Economics, Elsevier, 206(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104587.

Axinn, W. G., & Pearce, L. D. (2016). Mixed Method Data Collection Strategies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ayuba, A., Saad, N., & Ariffin, Z. Z. (2016). Does Perceived Corruption Moderate The Relationship Between Economic Factors and Tax Compliance? A Proposed Framework for Nigerian Small and Medium Enterprises. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 7(1), 402-409. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n1p402.

Bani-Khalid, T., Alshirah, F. A., & Alshirah, M. H. (2022). Determinants of Tax Compliance Intention Among Jordanian SMES: A Focus on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Economies MDPI, 10(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10020030.

Botlhale, E. K. (2019). Tax and Customs Duty Administration in Botswana. Botswana Notes and Records, 51.

Botswana Unified Revenue Service Annual Reports: (2012, 2017 and (2019)). Gaborone.

Peprah, C., Abdulai, I, & Agyemang-Duah, W. (2020). Compliance with Income Tax Administration Among Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Ghana, Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1782074. https://doi.10.1080/23322039.2020.1782074.

Cobham, A. (2022). Tax Injustice. 2022 International Monetary Fund.

David, & David (2016). Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases; 15ed. Essex, England: Pearson Education.

Eboziegbe, M. O. (2007). "Tax Evasion Hinders Local Governments." Saturday Tribune, October: 13.

Gale, W. G., & Samwick, A. A. (2014). Effects of Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth. The Brookings Institution and Tax Policy Center. January 2014 SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2494468.

Green, S. P. (2019). What's Wrong with Tax Evasion? Houston Business and Tax Law Journal.

Hofmeyer, C. (2013). Tax Administration Criminal Offences.

Malkawi, H. Y. & Haloush, H. (2008). The Case Of Income Tax Evasion In Jordan: Symptoms And Solutions. July 2008 Journal of Financial Crime, 15(3), 282-294. https://10.1108/13590790810882874.

Manhire, J. T. (2015). What Does Voluntary Tax Compliance Mean? A Government Perspective. University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online. 164(11).

Mann, R. F. (2006). Beyond Enforcement: Top 10 Strategies for Encouraging Tax Compliance Tax Notes, (2006, May 22). University of Oregon School of Law. 111(8).

Hoxhaj, M., & Kamolli, E. (2022). Factors Influencing Tax Evasion of Businesses: The Case of Albania.

European Journal of Economics and Business Studies. January -June 2022. Issu

ISSN 2411-9571 (Print), (online), 8. https://doi.org/10.26417/233qcq96.

Mmegi Online-Pauline Dikaelo (2020). BURS Goes After Tax-Dodgy Landlords. Mmegi Online (March 20,2020).

Morse, M. (2015). Effects of Tax Evasion in the United States. Accounting, 16.

Najera, C. M. (2011). Southwestern Journal of International Law. Combating Offshore Tax Evasion: Why the United States Should Be Able to Prevent American Tax Evaders from Using Swiss Bank Accounts to Hide Their Assets.

Ndlovu, T. (2016). Fiscal Histories of Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Botswana. Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand, Working Paper Series: No.1, August 2016, (1), 25.

Onyeka, V. N., & Nwankwo, C. (2016). The Effect of Tax Evasion and Avoidance on Nigeria's Economic Growth. European Journal of Business and Management, 8(24).

Palil, M. R., & Mustapha, A. F. (2011). Determinants of Tax Compliance in Asia: A Case of Malaysia. European Journal of Social Sciences 24: 7-32; The Evolution and Concept of Tax Compliance in Asia and Europe. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 5(11), 557-563.

Pashev, K. V. (2015). Tax Compliance of Small Business in Transition Economies: Lessons from Bulgaria. Working Paper 05-10, Andrew Young School of Policy Studies: Atlanta Georgia.

Piolatto, A. S. E. (2014). Itemised Deductions: A Device to Reduce Tax Evasion. Universitat De

Barcelona & IEB. Accessed: (2022,

November 25). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2410921.

Prichard, W. Custers, A. Dom, R. Davenport, S., & Roscitt, M. (2019). Innovations in Tax Compliance Conceptual Framework. World Bank Group Policy Research Working Paper 9032. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-9032.

Ramfol, R. (2019). The Fine Line Between Tax Compliance And Tax Resistance: The Case Of South Africa October 2019 Conference: International Conference of Accounting & Business, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Randlane, K. (2015). Tax Compliance As A System: Mapping the field. International Journal of Public Administration, 39, 515-525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1028636.

Saidu, S., & Dauda, U. (2014). Tax Evasion and Governance Challeneges in the Nigerian Informal Sector. Journal of Finance and Economics, 2(5), 156-161. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfe-2-5-4.

Seitshiro, K. (2022). Two BURS Senior Executives Suspended from Duty Over Corruption Allegations. Sunday Standard/The Telegraph, (2022 October 14).

Selatlhwa, I. (2018). 'Inside How Fong Kong Dealers Deny Government Of Millions Through Tax Evasion' The Mmegi, (2018 December 18).

Stiglingh, M., Anna-Retha, S., & Smit, A. (2022). The Relationship Between Tax Transparency and Tax Avoidance May 2020 South African Journal Of Accounting Research 36(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2020.1738072.

Tanzi, V. (2017). Corruption, Complexity and Tax Evasion. Paper Written for Presentation at the "Tax and Corruption Symposium", Organized by the UNSW Business School, Sydney, IMF Staff papers. 19-20.

Tilahun, M. (2019). Determinants of Tax Compliance: A Systematic Review. Economics. 8(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.eco.20190801.11

Walt, V. D. J. (2012). DLA Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. Tax Alert on: blame it on the bean counters or not? News & Press: Case Law. Posted by: SAIT Technical. Accessed 05 October 2023, Friday, (2012 September 07).

Warner, G. (2015). Modeling Tax Evasion With Genetic Algorithms. Economics of Governance, 16(2), 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-014-0152-7

Whalen, J. (2020). Tax Cheats Deprive Governments Worldwide Of $427 Billion A Year, Crippling Pandemic Response: Study - The Washington Post (Democracy Dies In Darkness),(accessed on 24 November 2022) USA.

White, J. R. (2012). Tax Gap-Sources of Noncompliance and Strategies to Reduce It-GAO. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1782074.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2023. All Rights Reserved.