Rethinking Teacher Education in context to NEP 2020 and Multilingual Classrooms

Dr. Rajiv Kumar Singh 1![]() ,

Dr. Sunita Joshi Kathuria 2

,

Dr. Sunita Joshi Kathuria 2![]()

![]()

1 Director

(Academic), National Institute of Open Schooling, Noida, Delhi, India

2 Consultant (Research & Evaluation), National Institute of Open

Schooling, Noida, Delhi, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 represents a transformative shift in India's educational landscape, particularly concerning multilingual education. As a comprehensive framework, NEP 2020 advocates for the integration of mother tongue or regional language instruction in the early years of education, underscoring the policy's commitment to preserving India's rich linguistic diversity while enhancing educational outcomes. Multilingual education is grounded in the belief that children learn best when they are taught in their mother tongue or a language familiar to them. Therefore, this idea has been strongly recommended by the policy which promotes the use of the mother tongue or regional language as the medium of instruction up to Grade 5, and wherever possible, up to Grade 8. This approach was taken up to improve comprehension, cognitive development, and academic performance by aligning the language of instruction with the students' linguistic background. Furthermore, NEP 2020 also encourages the learning of additional languages, promoting multilingualism as a means to foster cognitive flexibility, cultural understanding, and global competencies. In this paper,

the authors attempted to explore the core elements of NEP 2020 relevant to

multilingual classrooms, the anticipated impacts on educational practice, and

the challenges and opportunities presented by its implementation. In addition

to many benefits, the authors observed a few challenges in its implementation

in Indian classrooms. One major obstacle was the lack of qualified teachers

who can instruct in a multilingual environment and are fluent in multiple

languages. Another major barrier worth mentioning was the development and

distribution of teaching materials in multiple languages. The authors of this

paper emphasize how critical it is to reconsider and consistently work on the

curriculum of teacher preparation programs in order to

incorporate the high demand aspects of today’s educational scenario. In

conclusion, the authors strongly believe that by overcoming the challenges

and taking advantage of the opportunities presented by NEP 2020, India can

progress toward a more successful and equitable educational system that

honors and builds upon its rich linguistic heritage. |

|||

|

Received 02 October

2024 Accepted 09 November 2024 Published 31 December 2024 Corresponding Author Dr.

Sunita Joshi Kathuria, sunitkath.nios@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v12.i12.2024.5802 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: NEP 2020, Multilingualism, Indian

Classrooms, Challenges, and Teacher Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

India's rich heritage of culture and historical development are reflected in its linguistic landscape, which is found to be among the most diverse and complex in the world. India is a testament to the coexistence of numerous linguistic traditions, with over 19,500 languages and dialects spoken throughout its enormous geographic area. The Census of India 2011 officially recognizes 121 languages spoken by more than 10,000 people each, but the reality is far more intricate, with many local languages and dialects spoken by various communities Kumar (2019), Mohanty (2019). This diversity is mirrored in the country's educational, social, and political spheres, making language a critical aspect of identity and communication in India. In such a diverse linguistic landscape, the education system is tasked with the formidable challenge of accommodating multiple languages within the classroom, ensuring that learners from varied linguistic backgrounds receive equitable educational opportunities.

If we see the complete linguist scenario of Indian classrooms, multilingual classrooms are not just an expectation; they are a necessity to cater to the diverse linguistic backgrounds of learners. The intricate sociolinguistic context of the country is reflected in these classrooms, as children frequently grow up in multilingual environments speaking one language at home, one in the community, and a third in formal educational settings. Teachers face a variety of opportunities and challenges as a result of the multiple languages spoken in one classroom. It is therefore true to state that they must possess both subject-matter expertise and the ability to navigate the complexities of language dynamics.

Let's explore more about India's linguistic landscape before moving on:-

The Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution recognizes 22 languages, including major languages like Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, Hindi, and Marathi. While English continues to be used extensively in administration, the judiciary, and education, Hindi, in its Devanagari script, is the official language of the central government. As stated above, the linguistic reality of India, however, is far more diverse than these designated languages. As the main languages of literature, media, and communication in their individual states and communities, regional languages are highly significant both culturally and emotionally. For instance, Bengali in West Bengal, Tamil in Tamil Nadu, and Marathi in Maharashtra are not just languages; they are integral parts of the people's cultural identities and traditions. Furthermore, there are many languages and dialects spoken by indigenous people and in rural areas that are vital to their cultural survival but are frequently left out of mainstream discourse. The Census of India, 2011 reveals that the population of India communicates 121 major languages. There are over a thousand spoken dialects in this country, which is home to hundreds of languages and dialects. India's languages are divided into four main language families: Austroasiatic (including Santali and Khasi), Dravidian (which includes Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada), Indo-Aryan (which comprises Hindi, Bengali, and Marathi), and Tibeto-Burman (that includes Manipuri and Bodo). India has 1,369 dialects as per the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (PLSI). Dialects are regional or local variations within a language. These languages are passed down through generations orally and are often closely linked with local traditions, rituals, and knowledge systems. However now a days, many of these languages face the threat of extinction due to the supremacy of more widely spoken languages and the increasing influence of globalization, which favors languages like English and Hindi Agnihotri (2017).

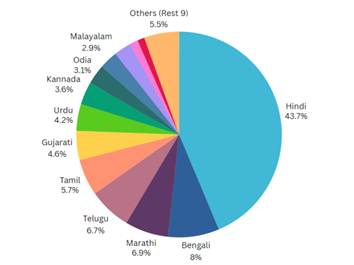

We may notice that while many languages are spoken, a few dominate in terms of the number of speakers. The following graph Figure 1 depicts the percentage of the language spoken by Indians. According to the Census 2011, Hindi is the most widely spoken language in India (43.7%), followed by Bengali (8%), Marathi (6.8%), Telugu (6.7%), Tamil (5.7%), Gujarati (4.5%), Urdu (4.1%), Kannada (3.6%), and Odia (3.1%).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Percentage of languages Spoken in India (Census of India, 2011) |

2. Languages in Indian Classrooms

On examining the role of language in the Indian classrooms and their impact on a child's overall development, we may get to understand that language does play a significant role. The multilingual nature of the country presents both opportunities and challenges for teachers and other stakeholders. While multilingualism can enhance cognitive abilities and cultural awareness among students, it also requires careful planning to ensure that all languages are given due importance in the educational curriculum. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recognizes this diversity and emphasizes the need for a multilingual approach to education, advocating for the use of the mother tongue or regional language as the medium of instruction in early education (Bhattacharya, U., & Jhingran, D., 2020). It represents a watershed moment in India's educational landscape, marking a shift towards a more holistic, flexible, and inclusive education system. The policy highlights that this linguistic diversity is not just a cultural treasure but also a crucial educational resource. In the context of Indian classrooms, the policy’s advocacy for the mother tongue or regional language as the medium of instruction up to at least Grade 5, and preferably till Grade 8, underscores the importance of linguistic inclusivity in education Shukla & Pandey (2021. This move aims to ensure that students can learn in a language that they understand best, thereby reducing the cognitive load and improving educational outcomes. The policy truly believes that multilingualism is rooted in the understanding and accepting that children learn best in their mother tongue and that early education in a familiar language can significantly enhance comprehension and cognitive development Bhattacharya (2021).

Many ancient scriptures emphasize the importance of utilizing a child's mother tongue or regional language for their development. Nonetheless, the importance of education and clear communication is also emphasized in the Bhagavad Gita and other ancient Indian texts.

A Sanskrit verse states:

शिक्षा मूलं मातृभाषा, तत्र ज्ञानं संप्रवर्तते।

यस्य वाक्ये जन्मभूमेः, स बालः सत्त्ववान भवेत्॥

It means: The mother tongue is the cornerstone of education since it is the natural language. A child who speaks the language of their origins develops virtue and wisdom. Moreover, it also emphasizes how crucial it is to raise kids in their mother tongue or region, as doing so is vital to their overall growth and comprehension.

Now, let us understand the multi-lingual approach of NEP 2020 in detail:-

This approach is not merely about language learning; it is also about fostering cognitive flexibility, enhancing problem-solving skills, and encouraging creativity. Furthermore, a great deal of research indicates that teaching kids in a language they feel most at ease in, helps them to learn in the best manner. In order to create a multilingual society that is better prepared to engage in a globalized world, NEP 2020 also supports the teaching of multiple languages from an early age. As part of the "three-language formula," which consists of the mother tongue, a regional language, and an international language—typically English—the policy suggests that students be exposed to three languages. The objective of this multilingual exposure is to promote an appreciation for inclusivity and cultural diversity in addition to improving language proficiency. Additionally, the policy acknowledges the cognitive advantages of multilingualism, including enhanced memory, increased mental flexibility, and better executive functioning.

Following case studies will set a tone for us to understand the need of having multilingualism in Indian classrooms:

1) A study by the Azim Premji Foundation (2018) revealed that Tribal communities in Jharkhand face educational challenges due to a language barrier in schools where Hindi is the medium of instruction, while tribal languages are widely spoken at home. When the students were taught in their tribal language, it resulted in increased engagement and improved academic performance among tribal students. Hence, this study proved that the use of a bilingual approach helped students better understand the curriculum, improving retention rates and learning outcomes.

2) The Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) in 2017 conducted a study which revealed that in Ladakh, a bilingual education model was introduced to support Ladakhi-speaking students, who otherwise struggled with Hindi and Urdu as mediums of instruction and it was found that the incorporation of Ladakhi alongside Hindi and Urdu resulted in improved understanding, enhanced classroom participation, and smoother language transitions.

3) A study by the Centre for Equity Studies (2019) revealed that with the influx of migrant laborers from different linguistic backgrounds, Kerala's classrooms have become linguistically diverse which came out to be a big challenge for the teachers. And, when schools began adapting a multilingual curriculum to support these students, providing education in both the students' mother tongues and Malayalam, the academic success and social integration of migrant students' increased.

4) A study carried out by NCERT (2021) revealed that Delhi’s classrooms were becoming increasingly multilingual due to migration from various states. The educational policy predominantly focuses on Hindi and English, creating challenges for students from non-Hindi-speaking backgrounds. The study also found that students from linguistic minorities when taught using a multilingual approach demonstrated improved academic performance.

5) Another study conducted by the University of Hyderabad (2022) surfaced the similar concern. In an effort to provide students with global language skills, Andhra Pradesh introduced English-medium instruction in schools. However, this shift created challenges for students from non-English-speaking backgrounds. It was found that students struggled with English-only instruction. However, schools that employed a gradual, bilingual transition using Telugu and English reported better comprehension and learning outcomes.

The aforementioned case studies highlight the necessity of multilingual education in Indian classrooms. Multilingual education has been repeatedly demonstrated to improve student comprehension, cognitive development, and academic success—regardless of the setting—be it urban, rural, or tribal.

Though the research in education proves that multilingualism is commendable, its implementation presents significant challenges, particularly in a country as diverse and complex as India Mohanty et al. (2021). One of the primary challenges observed was the availability of qualified teachers who are proficient in multiple languages. In many regions, there is a shortage of teachers who can effectively teach in the mother tongue or regional language, especially in remote and rural areas where linguistic diversity is most pronounced. Studies indicated that the dearth of proficient multilingual educators had, to some extent, impeded the successful execution of the policy and resulted in disparities in the caliber of instruction given to pupils with varying linguistic backgrounds. Another challenge lies in the development of appropriate teaching and learning materials. Most textbooks and educational resources are currently available only in a few dominant languages, such as English and Hindi. The NEP 2020’s emphasis on multilingual education requires the creation of a vast array of resources in multiple languages, which can be a daunting task given the sheer number of languages spoken in India. Moreover, the translation of complex educational content into various regional languages without losing meaning or nuance is a significant challenge that requires careful planning and execution.

Furthermore, the NEP 2020’s multilingual approach requires a significant shift in the mindset of educators, policymakers, and society at large. For decades, English has been perceived as the language of upward mobility and social prestige in India. This perception has often led to a preference for English-medium education, even at the cost of students’ comprehension and cognitive development. The policy’s emphasis on mother tongue education challenges this deeply entrenched belief, necessitating a broader societal change in how language and education are perceived Panda & Mohanty (2009).

Additionally, implementing a multilingual curriculum across states with diverse linguistic profiles poses one of the biggest logistical challenges. India’s federal structure allows states significant autonomy in determining their education policies, and this lead to variations in how the NEP’s multilingual recommendations are adopted and implemented.

All these above challenges highlight that there is a big need to ensure consistency in the implementation of the policy across different states, while also respecting regional linguistic diversity, as it requires a delicate balance and effective coordination between the central and state governments.

3. Opportunities in Multilingual Education

The scope of multilingual education in India is vast, driven by the country's rich linguistic diversity and the evolving demands of a globalized world. Multilingual education not only aligns with India's constitutional commitment to preserving linguistic diversity but also offers numerous opportunities to enhance cognitive, social, and economic outcomes for students Zhang & Sun (2019). Improving educational equity and inclusion is one of the most important opportunities in multilingual education Skutnabb-Kangas & Heugh (Eds.). (2011). It guarantees that children from different linguistic backgrounds have a better chance of understanding and engaging with the curriculum by offering instruction in the mother tongues of the students. This is especially crucial in rural and tribal communities, where students frequently speak languages other than the ones that are typically taught in schools. By decreasing dropout rates and enhancing literacy and numeracy outcomes for these underprivileged populations, multilingual education can aid in closing this gap Varghese & Staehr (2020).

Beyond just helping students learn languages, multilingual education in India has been shown to have additional cognitive benefits. Studies have indicated that pupils who are multilingual exhibit improved memory, increased cognitive flexibility, and improved problem-solving abilities. These benefits are especially pertinent in the globalized world of today, where it is becoming more and more important to be able to think critically and adjust to various cultural settings. India can better equip its students for the global job market by encouraging multilingualism at a young age. This will create opportunities for both domestic and foreign employment and higher education.

Furthermore, multilingual education has the potential to strengthen social cohesion and national unity. In a country as diverse as India, where linguistic and cultural differences often intersect with social and political divisions, multilingual education can foster mutual respect and understanding among different linguistic communities. By learning multiple languages, students gain insights into different cultures and perspectives, which can help reduce prejudice and promote social harmony. This is particularly important in the context of India's federal structure, where linguistic diversity is a defining feature of many states.

The economic opportunities associated with multilingual education are also significant. In a global economy where multilingualism is an asset, India's emphasis on multilingual education can enhance the employability of its workforce. Knowledge of multiple languages can open doors to careers in international business, diplomacy, translation, and information technology, among others. Moreover, the growing demand for multilingual content in media, entertainment, and education offers new opportunities for entrepreneurs and professionals in these sectors.

Finally, the scope of multilingual education in India extends to the preservation and promotion of the country's linguistic heritage. With many indigenous languages at risk of extinction, integrating these languages into the formal education system can help preserve them for future generations. This not only contributes to cultural diversity but also enriches the educational experience by connecting students with their cultural roots.

4. Teacher Education and Capacity Building

For the NEP 2020’s multilingual vision to be realized, significant investments in teacher education and capacity building are essential. As mentioned above, teachers need to be trained not only in the pedagogical methods required for multilingual education but also in the cultural competencies necessary to navigate the complexities of India’s diverse classrooms Vijayakumar & Yadav (2022). Hence, teacher education programs must be restructured to include modules on multilingual education, language acquisition, and sociolinguistic awareness.

Now let us talk about the role of Teacher Education and challenges faced by teachers

The traditional model of teacher education, however, has often been criticized for its one-size-fits-all approach, which fails to address the specific needs of multilingual settings. Teacher education for multilingual classrooms involves much more than just teaching in multiple languages. It requires an understanding of:-

· linguistic theories,

· language acquisition processes,

· sociolinguistic contexts, and

· the ability to create an inclusive environment where all languages are valued and used as resources for learning.

Teachers need to be prepared to identify and deal with the difficulties that multilingual students encounter, including language hurdles, cultural differences, and uneven language proficiency. The language gap that exists between the teacher and the students is one of the main difficulties that teachers encounter in multilingual classrooms. Many times, teachers are not fluent in the languages that their students speak which creates communication barriers and impedes learning. This is especially true in India's remote and rural areas, where teachers frequently have different linguistic backgrounds from their pupils. Furthermore, this problem is made worse by the fact that English is the primary language of instruction in many schools, making it difficult for students who are not fluent in the language to keep up with the curriculum. The absence of suitable teaching resources and materials for multilingual classrooms is a serious problem as well. Students who speak different languages are disadvantaged by the majority of textbooks and learning resources, which are typically written in English or the predominant regional language. A disconnect between the home language and the language of instruction caused by this lack of resources may result in subpar academic performance and a higher dropout rate. Additionally, there can be an excessive amount of cognitive strain placed on students in multilingual classrooms. It can be mentally taxing to multitask in multiple languages, especially for young learners who are still honing their language skills. Instructors need to be prepared with techniques to lessen this cognitive burden and help students in adjusting to their multilingual surroundings.

India has the potential to establish an education system that not only values its linguistic diversity but also uses it to improve learning outcomes for all students by providing teachers with the necessary training and resources. Instructors ought to be prepared to leverage students' linguistic diversity as a resource for learning, encouraging them to apply all of their linguistic skills to improve their comprehension of novel ideas. A paradigm shift in how teacher education is conceptualized, delivered, and sustained is required to ensure that teachers are fully equipped to foster inclusive and effective learning environments.

First and foremost, teacher education programs must prioritize multilingual pedagogy as a core component of their curriculum Mohanty et al. (2021) and Bose (2021). Educators need to be well-versed in the cognitive benefits of multilingualism and be able to leverage students' linguistic resources as assets in the learning process Menon & Agnihotri (2020). Furthermore, teacher training institutions should integrate modules that focus on the latest research in language acquisition, bilingual education, and language-sensitive pedagogy, ensuring that future teachers are prepared to address the needs of a multilingual student population Kumar & Gupta (2022). Moreover, continuous professional development (CPD) should be re-imagined to support in-service teachers in multilingual classrooms. CPD programs need to be more accessible, context-specific, and reflective of the diverse linguistic realities across India Ghosh (2021). This can be achieved through a blend of in-person workshops, online courses, and peer-learning communities that allow teachers to share best practices and collaborate on multilingual education strategies Yadav & Sharma (2021). Additionally, there should be a focus on mentorship and coaching, where experienced educators guide and support new teachers in developing effective multilingual teaching practices Rajput & Sharma (2022).

Collaborative efforts between government bodies, educational institutions, and community organizations are crucial in this rethinking process. State governments should work closely with local communities to understand the specific linguistic needs of their regions and tailor teacher education programs accordingly. Partnerships with non-governmental organizations and international bodies can also bring in new perspectives, resources, and innovative approaches to multilingual education. For example, adopting and adapting successful models from other multilingual countries can provide valuable insights into what works in different contexts.

Technology will play a pivotal role in the way forward. Digital tools and platforms can be harnessed to provide multilingual resources, facilitate language learning, and support teachers in their professional development. Online training modules, virtual classrooms, and e-learning platforms can make teacher education more flexible and scalable, reaching educators in even the most remote parts of the country. Additionally, technology can enable the creation of a national repository of multilingual teaching resources, lesson plans, and assessment tools, making them easily accessible to all educators. Hence, rethinking teacher education for multilingual classrooms in India requires a comprehensive and collaborative approach. By embedding multilingual pedagogy into teacher training, supporting continuous professional development, leveraging technology, and fostering partnerships, India can build a cadre of teachers who are not only linguistically skilled but also culturally responsive and inclusive in their teaching practices. This re-imagined approach will ensure that every student, regardless of their linguistic background, has access to quality education, thereby contributing to a more equitable and just society.

5. Conclusion

Growing awareness of the value of bilingual education in India in recent years has prompted a number of initiatives targeted at improving teacher preparation for bilingual classrooms. For example, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recommends that students be taught in their mother tongue or regional language until at least Grade 5, emphasizing the need for multilingual education. This change in policy emphasizes how crucial it is to protect linguistic diversity and how teacher preparation programs must support these objectives. A number of Indian organizations and institutions dedicated to teacher education are also addressing the difficulties associated with multilingual education. To assist teachers in promoting multilingual education, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), for instance, has created guidelines and resources. These resources include multilingual textbooks, teacher training modules, and instructional strategies that cater to diverse linguistic backgrounds. Moreover, various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community-based initiatives are working to promote multilingual education in India. These initiatives often focus on providing training and resources to teachers in rural and remote areas, where linguistic diversity is most pronounced. By collaborating with local communities and leveraging indigenous knowledge, these initiatives are helping to bridge the gap between formal education and the linguistic realities of Indian classrooms.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 marks a significant shift in India's approach to education, particularly in its emphasis on multilingualism as a foundational element of learning. By advocating for mother tongue or regional language instruction during the early years of schooling, NEP 2020 acknowledges the cognitive, cultural, and social benefits that come with nurturing a child's linguistic heritage. This policy represents a progressive step towards creating an education system that is more inclusive, equitable, and reflective of India's rich linguistic diversity. However, a coordinated effort from all stakeholders—including governmental organizations, educational institutions, teachers, and communities—is necessary to successfully implement NEP 2020's vision for multilingual classrooms. Obstacles such as lack of resources, including multilingual teaching materials, qualified teachers fluent in local languages, and suitable infrastructure to facilitate multilingual education are on the way which can be taken of by large investments in professional development and teacher education.

While the NEP 2020 provides a broad framework, its implementation must be tailored to the specific needs of different regions, considering the varied linguistic demographics and educational challenges. This requires a bottom-up approach, where local communities and educational authorities play a pivotal role in shaping how multilingual education is delivered in their respective contexts. The way forward will require collaboration, innovation, and a commitment to ensuring that every child, regardless of their linguistic background, has access to quality education that honors their cultural and linguistic identity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agnihotri, R. K. (2017). Multilinguality

and the Teaching of languages

in India. Language and Language

Teaching, 6(1), 1-9.

Annamalai, E. (2012). Social Dimensions of language Change.

Cambridge University Press.

Azim Premji Foundation. (2018). Learning in Tribal Schools: Impact of Language on Student Outcomes. Azim Premji Foundation.

Bhattacharya, S. (2021). The Impact of NEP 2020 on Multilingual Education. Journal of Educational Policy, 25(2), 154-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.1924314

Bose, K. (2021). Teacher education for Multilingual Classrooms: Rethinking Pedagogy under NEP 2020. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 20(3), 207-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1875839

Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL). (2017). The Role of Bilingual Education in Improving Academic Outcomes in Ladakh. CIIL Research Journal.

Centre for Equity

Studies. (2019). Multilingual Education and Migrant Students

in Kerala: Addressing Linguistic Diversity in Classrooms.

Journal of Equity Studies,

24(3), 112-135.

Ghosh, S. (2021). The Role of Teacher Education in Implementing NEP 2020's Multilingual Vision. Indian Journal of Teacher Education, 55(2), 92-108.

Government of India. (2020). National Education Policy 2020. Ministry of Human Resource Development.

Kumar, K. (2019). Language Policy and Multilingual Education in India: An Analysis. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 7(3), 234-245. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijll.20190703.12

Kumar, K., & Gupta, A. (2022). Rethinking language Teacher Education Under the NEP 2020: Challenges and Possibilities. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 9(2), 45-60. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijll.20220902.12

Menon, S., & Agnihotri, R. K. (2020).

Teacher Preparation for Multilingual

Education in India: Perspectives from NEP 2020.

Education and Society, 42(1), 99-115.

Mohanty, A. K. (2019). The Multilingual Reality:

Living with languages. Multilingual Matters.

Mohanty, A. K., Panda, M., &

Pal, R. (2021). Multilingual

Education in India: Current

Challenges and Future Directions. International Journal of Multilingual

Research, 13(4), 543-562.

National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). (2021). Multilingual Education in Delhi Government Schools: A Path to Inclusive Learning. NCERT Journal of Educational Research, 9(4), 101-125.

National Council of Educational Research and Training. (2005). National Curriculum Framework .

North East Regional

Institute of Education. (2020). Bilingual

Education in North-East India: Impacts on Student Learning and Engagement. NERIE Research

Reports, 6(2), 56-78.

Panda, M., & Mohanty, A. K. (2009). Language Policy and Education: Towards Multilingual Education. In T. Skutnabb-Kangas, R. Phillipson, A. K. Mohanty, & M. Panda (Eds.), Social justice through multilingual education (pp. 217-238). Multilingual Matters.

Rajput, M., & Sharma, P. (2022). Preparing Teachers for Multilingual Classrooms: Insights from the National Education Policy 2020. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43(1), 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.1968402

Shukla, S., & Pandey, V. (2021). NEP 2020 and the Need for Multilingual Teacher Education: An Indian Perspective. Journal of Educational Change, 23(3), 251-265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09400-6

Skutnabb-Kangas, T., & Heugh, K. (Eds.).

(2011). Multilingual

Education and Sustainable Diversity work:

From Periphery to Center. Routledge.

Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). (2020). The Impact of Bilingual Education on Student Learning in Rural Maharashtra. TISS Working Paper Series, 8(5), 78-93.

UNESCO. (2016). If you don't understand, how can you learn?. Global Education Monitoring Report.

University of Hyderabad. (2022). Bilingual Education and Its Impact on Learning in Andhra Pradesh: A Comparative Study of Monolingual and Multilingual Schools. Journal of Language and Education Policy, 10(2), 144-168.

Varghese, M., & Staehr, L. (2020). NEP 2020 and the Vision for Multilingual Education in India. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 12(1), 45-60. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajess/2020/v12i130221

Vijayakumar, P., & Yadav, S. (2022). Bridging the gap: Implementing Multilingual Education Strategies in Indian schools. Educational Research Review, 17(3), 189-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100310

Yadav, S. K., & Sharma, R. (2021). Exploring the Role of Teachers in Multilingual Classrooms Under NEP 2020. Journal of Language and Education Policy, 15(2), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2021.1957891

Zhang, Y., & Sun, X. (2019). Language Education Policies and their Implications for Multilingual Education: Insights from India. International Journal of Multilingualism, 16(1), 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2018.1557372

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2024. All Rights Reserved.