Western Education in Maldah: A Case Study on the Spread of Western Education in Maldah District (1858-1905)

1 M.

Phil Scholar, Sikkim University, Gangtok, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

It is true

that education is the pillar of a nation and continuously plays a significant

role in the progress of any region or country. Since ancient times, different

parts of the world have had their kind of education system, just as India

has. But, over the time, the educational structure in India has transformed

its nature and character, for example, the Gurukul system of

education, then the Sangha or Mahavihara system of education,

etc. In ancient times universities like Nalanda, Taxila, Odantapuri, etc.,

were established and became prominent learning centres. Then, in the

seventeenth century when the Europeans came to India, they introduced Western

education particularly the English education system in India. And this new

system of education is still influencing India at present. Though Western

education system was introduced by the British it gradually began to

influence the nation. Hence, this research paper will be dealing with the

development of Western education in the Maldah district before the partition

of Bengal. It will also discuss the literacy rate of the district of that

time. |

|||

|

Received 07 April

2024 Accepted 11 May 2024 Published 10 June 2024 Corresponding Author Himansu

Barman, himansubarman.hb@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v12.i5.2024.5634 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Chatushpathi, Chaubarish, Maktaba,

Madrasa, Missionary, Pathshala, Western Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The educational history of India is a diverse arena yet to be discovered to its greatest potential. The history of education and its growth in India suggests several potentials for study and research. A detailed study of the educational evolution and growth in India would throw light upon numerous noteworthy changes and upheavals in the arena of education through its history in the colonial period. The footing of colonial rule unlocked the space for the growth of Western education (primarily English education) in several Indian provinces i.e., Bombay, Madras, etc. In the same way, western education grew effectively in Bengal and the district of Maldah was not left untouched. Therefore, Maldah found itself firmly, from the early times, inside the educational topography of India throughout the colonial period.

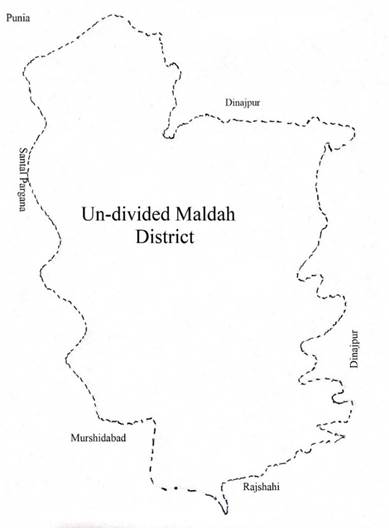

The Maldah district is referred to as the entrance gate of North Bengal. Before independence, Maldah was in the north-west corner of the Bengal province, positioned between 87°48' and 88°33'30" east longitudes and 24°30' and 25°32'30" north latitudes. It was bounded on the south by Rajshahi and Murshidabad districts, on the north by Purnia and Dinajpur districts, on the west by Murshidabad, the Santal Parganas and Purnia districts, and on the east by Dinajpur and Rajshahi districts. Carter (2013).

Map 1

|

Map 1 Un-divided Maldah District Before Partition of India Source Sarkar,

Ashutosh. “Sapha Hor Movement in North Bengal: A Study on its Various

Dimensions in the Twentieth Century.” Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, The

University of Burdwan, 2015. |

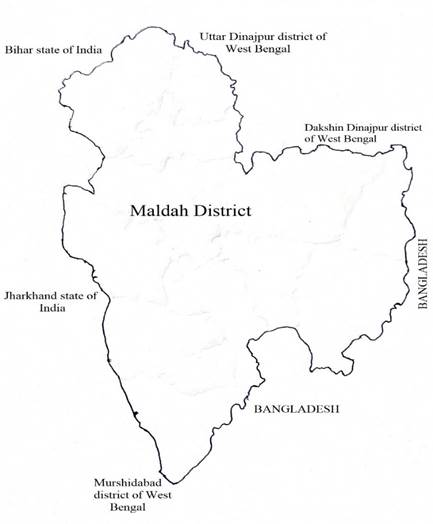

However, after independence, its geographical borderline was changed because some areas (police stations) of this district went to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Now it is surrounded on the south by the district of Santal Pargana in Bihar (now Jharkhand) and the district of Murshidabad in West Bengal. On the north the district of North Dinajpur and South Dinajpur in West Bengal and the district of Purnia in Bihar. On the west the Santal Pargana (now Jharkhand) and Purnia in Bihar. On the east, it is bounded by the border with East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The latitude range of the Maldah district covers from 24°40'20" north to 25°32'08" north, lying completely to the north of the Tropic of Cancer. The easternmost point of the district is defined as 87°45'50" east to 88°28'10" east longitude. According to the Surveyor-General of India, the district covers an area of approximately 1436 square miles. Sengupta (1969).

Map 2

|

Map 2 Maldah District After Partition of India Source Mandal,

Pronob. “Educational and Employment Status of the Scheduled Tribes Population

in Malda District, West Bengal”. Unpublished Ph.D

Thesis, University of North Bengal, 2019. |

Also, the Ganga River is situated along the district's western and southwestern margins. The district's head office English Bazaar, is located at the centre of the district at 25°0’14” north latitude and 88°11’20” east longitude. Lambourn (2004). Maldah has a substantial historical background, with much of its region being the hub of civilisation and culture in ancient times. It was home to more than a few renowned capital cities, together with Ramabati, Gour, Lakhanauti, Tanda, and Pandua. Moreover, Maldah was nearby to Deokot (Devikot), the earliest Muslim capital of Rajmahal, and Bengal.

The ancient and medieval capitals of Gaur and Pandua was transformed into the city of English Bazar and the district of Maldah. After the foothold of East India Company’s trading factory, the district was formed in 1813 out of portions of Purnia (Bihar), Dinajpur (Bengal), and Rajshahi (now Bangladesh) divisions. Carter (2013). Before the arrival of the East India Company, there were numerous pathshalas, maktabas, madrasas and chatushpathis or Chaubarish for Hindu and Muslim students, and these pathshalas and maktabas were the backbones of education. The dimensions of these homegrown institutes i.e., pathshala, madrasa etc. were not fixed and they were made in thatched mud rooms or under shade trees, and even the number of students varied depending on the area. Many pathshalas were established to be the homes of the Gurus (teachers) and sometimes gurus, students, parents, and local people would organise the pathshalas together. Even though there was a need for madrasa and pathshala in a village, but the institute (pathshala, maktab) could not be opened due to a lack of gurus. Hamilton (1833).

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the English East India Company's commercial actions amplified rapidly in Bengal. Christian missionaries took advantage of this prospect to carry out their activities in Bengal. Along with the creation of trading posts in Maldah, the indigo trading group of the British East India Company set up indigo factories in various areas of Maldah and wanted to spread Christianity to common people. It is against the environment of such actions that Western education started developing in Maldah. In June 1794, William Carey a Christian missionary came to the Madnabati village (30 miles north of Maldah town) as the superintendent of an indigo factory. Missionaries desired to spread the European education system in the country and William Carey joined this idea and established a primary school with 40 students at Madnabati village in Maldah. This was the first effort by the missionaries to spread the Western education system in Maldah. But in 1797 or 1799 William Carey left Maldah and went to Shrirampur on the order of the missionaries. Although William Carey left, numerous western schools were foundered by Mr. John Ellerton an indigo plant officer in Maldah between 1803 to 1805, among them, there were some schools in Goalmalati too. Basak (1965). In another place schools in Maldah were continual according to Robert May’s plan and the centre of these schools was Chuchura or Chinsura in the Hooghly. Robert May set up an unpaid school in his home to teach Braille, and after some days, Mr. May set up numerous other schools. When Mr. May passed away in 1818, the total number of schools in Bengal was 36 and the number of students was around three thousand. Mr. Robert May’s list of these schools included Mr. Ellerton’s schools in Maldah, so Ellerton managed these schools in Maldah according to Robert May’s ideas.

The formation of the Supreme Court in Calcutta in 1777 amplified the financial power of the English language. Although there were no respectable institutions for learning English at this time, countless Bengalis tried to learn English impartially in the late 18th and early 19th eras. The East India Company extended its commercial territory but did not want to interfere with education in the country. But the first time, through the Charter Act of 1813, the British parliament accepted a proposal to spend one lakh rupees a year for the development of education among the indigenous people of the British territories in India. Ghosh (1995). The Charter Act of 1813 stated – “it shall be lawful for the Governor General in Council to direct that… a sum of one lac of rupees in each year shall be set against and applied to the revival and improvement of literature and the encouragement of the learned natives in India, and for the introduction and promotion of a knowledge of sciences among the inhabitants of the British territory in India”. Ghosh (2020). However, diverse types of alterations arose regarding the medium of instruction at this time, according to some, Indians should be imparted in the Oriental education system, while others supposed that Western education must be spread. Finally, two institutions were established with mutual efforts to expand education. These establishments were the Calcutta School Society (September 1818) and the Calcutta School Book Society (May 1817). The Book Society intended to produce, publish, and print educational books at a very low cost. Although the primary aim was to publish books in English and Bengali medium, they also functioned in the preparation of books in Arabic, Sanskrit, and Persian languages. The Book Society carried about an inordinate change in the educational development of the schools with the publication of books on several subjects such as astronomy, geography, and history. In school education, the students were organized into different classes. Moreover, assistance was obtainable to the indigenous pathshalas with some conditions. It was specified that the funding would remain exclusively for those pathshalas that follow the syllabus stated by the education department and implement the instruction method as mentioned by the inspector allocated to the education department. These observant officers assisted the pathshalas guru to clarify the subject if there was any trouble for understanding. The inspection system was fixed twice a year and the presence of an examiner throughout the examination was made necessary. As a result, grounded on the students’ outcomes, the teacher was given certain help and meritorious students were awarded fellowships or scholarships. The Calcutta School Society endeavoured to start schools in and everywhere in Kolkata and make available for the training of teachers. Nevertheless, the books printed by the Calcutta Book Society reached one district to another district, and one village to another village in rural Bengal. Therefore, western education slowly started in native pathshalas and madrasas. Ghosh (2020).

The renewal of the Charter Act by the East India Company in 1853 marked the beginning of an educational policy in India. Wood's dispatches of 1854 provided insight into the company's educational objectives, emphasizing the propagation of European knowledge and science. The means to achieve this included English language instruction in higher education and vernacular languages for the broader populace. Wood's dispatch also proposed the establishment of a university and a separate education department in Bengal, headed by a Director of Public Instruction. This led to the introduction of government-funded schools with specific conditions for aid. Despite the East India Company's influence in Maldah since 1765, no government-supported English education institutions existed. Wood's dispatch outlined plans for government schools in various districts of Bengal, managed under a university. Following this directive, the University of Calcutta was founded in 1857, and in accordance, the Maldah Zillah School was established in 1858 under direct governmental oversight. District magistrates were appointed to oversee the administration of these schools. Ghosh (2020).

The Maldah Zillah School was established on July 10th, 1858, and it was located at the residence of indigo factory workers on the west side of the present S.P. bungalow. At its inception, government schools in the Bengal division were very few, including the Bankura, Jashore, Dhaka, Cumilla, Chittagong, Beulia, Barishal, and Sylhet schools, along with institutions like the Hindu School and Model Madrasa in Kolkata, and the Hooghly School, Srirampur Branch School, Triveni School, and Umarpur School in Hooghly. However, the Maldah Zillah School was prominent among them. Initially, it had 40 students, and until 1897, classes were conducted at its original location. During this period, the head teacher's salary was merely 15 rupees per month, while other assistant teachers earned 10 rupees or less. In the 1860s, Lieutenant Governor Sir J.P. Grant facilitated the provision of inexpensive textbooks for Zillah Schools' enhancement. Elementary education included Bengali, Grammar, Arithmetic, Retention, English, Geography, and Indian History. Students and teachers were incentivized for academic achievement, with rewards ranging from monetary compensation to educational resources. The school initially held two sessions, morning and afternoon, but shifted to a single session from 10 am to 4 pm in 1862. Writing on banana leaves with chalk was replaced with writing on sylet, enforced from the same year. The appointment of teachers was overseen by the district magistrate, who served as the president or chairman of the school's governing body. In 1863, the Middle Vernacular School was established in Maldah, alongside government and Middle Bengali schools. In 1901, the Middle Bengali School merged with the Maldah Zillah School, boosting its enrolment. The year 1901 marked a significant achievement for the school, as student Benoy Kumar Sarkar secured the top position in the Calcutta University entrance examination, reflecting the school's educational prowess and Maldah district's educational history. Ghosh (2020).

Following the establishment of the Maldah Zillah School, the advancement of Western education progressed rapidly, as evidenced by records in the Government Public Instruction, Gazetteer, and related sources. In 1856-57, there were two Government vernacular schools with 117 students. By 1860, one of these schools had transitioned into a middle English school, resulting in a total student count of 169. Lambourn (2004). According to the Public Instruction reports for 1862-63, there were three schools accommodating 295 students. General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower Province of the Bengal Presidency for 1862-63 (1864). By 1868-69, this number had increased to four schools serving 260 students. General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower Province of the Bengal Presidency for 1868-69 (1870). The below table is mentioned for more clarity:

Table 1

|

Table 1 The Number of Schools and Students in Maldah During 1862-63 and 1868-69 |

|||||||

|

Govt. Eng. School |

Govt. Vernacular School |

Grant-in-aid School |

|||||

|

Year |

School |

S. |

School |

S. |

School Name |

S. |

Total |

|

1862-63 |

Maldah Zillah School |

70 |

Maldah Sudder |

125 |

Nawabganj School |

100 |

3 schools with 295 students |

|

1868-69 |

Maldah Zillah School |

85 |

Maldah Sudder |

100 |

Nawabganj School |

35 |

4 schools with 260 students |

|

Kaliachack School |

40 |

||||||

|

Source General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower

Province of the Bengal Presidency for 1868-69 (1870). Calcutta:

Government of Bengal. Note S. indicates Students. |

|||||||

The data presented illustrates the expanding influence and

reach of Western education from urban centres to rural areas, marked by the

establishment of new schools and a growing number of students exposed to

Western educational methods. In the 1862-63 Public Instruction report for the

Maldah district, three schools were recorded: the Maldah Zillah School, a

full-fledged Government English school with 70 students; the Nawabganj School,

a Grant-in-aid Anglo Vernacular School with 100 students; and the Maldah

Sudder, a government vernacular school in English Bazar town with 125 students.

By the 1868-69 Public Instruction report, the total number of schools in the

district had increased to four. Among them, the Maldah Zillah School remained a

Government English school with 85 students, while the Maldah Sudder continued

as a Government Vernacular school with 100 students. Additionally, two

Grant-in-aid Middle schools were established in Nawabganj and Kaliachack,

serving 35 and 40 students respectively. This expansion reflects the growing

accessibility of Western education and the diversification of educational

offerings within the Maldah district.

In 1870, the Government aided a total of 4 English schools

and 14 vernacular schools, catering to 986 students. Lambourn (2004). However, significant

changes occurred in 1872 with the introduction of Sir George Campbell’s

education scheme aimed at enhancing the primary education system. This

initiative led to the inclusion of many indigenous village schools (pathshalas)

into the grant-in-aid program, previously overlooked by the state. The

Education Department's statistics for 1871-72 revealed 23 government and aided

schools along with 42 private schools, totalling 65 schools with 1893 students.

The following year, in 1872-73, the number of Government and aided schools

increased to 71, and private schools rose to 108, resulting in a total of 179

schools serving 4207 students. Hunter (1876). The provided table

illustrates the details of schools, students, and attendance for each category

of schools in the Maldah district during 1871-72 and 1872-73.

Table 2

|

Table 2 The Number of Schools and Students in Maldah During 1871-72 to 1872-73 |

||||||

|

Description of Schools |

Number of Schools |

Number of students on 31st

March |

Average Attendance |

|||

|

1871-72 |

1872-73 |

1871-72 |

1872-73 |

1871-72 |

1872-73 |

|

|

Higher Schools Government |

1 |

1 |

102 |

111 |

70 |

68 |

|

Middle Schools Government |

3 |

3 |

192 |

250 |

120 |

152 |

|

Middle Schools Aided |

13 |

12 |

558 |

612 |

343 |

410 |

|

Middle Schools Unaided |

2 |

1 |

59 |

28 |

40 |

23 |

|

Primary Schools Aided |

6 |

55 |

182 |

1613 |

114 |

1188 |

|

Primary Schools Unaided |

40 |

107 |

800 |

1593 |

… |

… |

|

Grand Total |

65 |

179 |

1893 |

4207 |

687 |

1841 |

|

Source William Wilson

Hunter, A Statistical Account of Bengal: District of Maldah, Rangpur, and

Dinajpur Vol. VII, (London: Trubner & Co., 1876), P. 122. |

||||||

The table provided demonstrates a remarkable increase in both the number of schools and students during the inaugural year of George Campbell's educational initiative. The rise in schools by 114 and the doubling of student enrolment underscore the program's swift impact. The surge in private schools can be attributed not only to better documentation of existing institutions but also to the incentive provided to teachers by the prospect of receiving government grants, prompting the establishment of new schools. It is noteworthy that this substantial expansion occurred without any increase in the overall cost of education to the Government.

The subsequent table containing statistics from the years 1873-74 to 1882-83, detailing Public Instruction data, is referenced in the following table.

Table 3

|

Table 3 The Number of Schools and Students in Maldah During 1873-74 to 1882-83 |

||

|

Year |

Number of Schools |

Number of Students |

|

1873-74 |

123 |

4246 |

|

1874-75 |

110 |

4176 |

|

1875-76 |

127 |

4358 |

|

1876-77 |

224 |

5292 |

|

1877-78 |

180 |

4320 |

|

1878-79 |

166 |

3718 |

|

1879-80 |

278 |

5835 |

|

1880-81 |

394 |

6639 |

|

1882-83 |

437 |

7884 |

|

Sources General Report

on Public Instruction in Bengal for 1873-74 to 1882-83. Calcutta: Government

of Bengal. |

||

Based on the provided table, there were fluctuations in the number of schools over the years, with decreases observed in 1874-75 and 1878-79, while increases were noted in other years, both in terms of schools and student enrolment. However, when analysing the period from 1873-74 to 1882-83, a significant overall rise in both primary and secondary schools, as well as student numbers, is evident in the Maldah district. Over this decade, the number of schools surged from 123 to 437, while student enrolment soared from 4246 in 1873-74 to 7884 in 1882-83.

Table 4

|

Table 4 The number of Students in Maldah During 1884-85 to 1888-89 |

|

|

Year of Public Instruction |

Number of Students |

|

1884-85 |

10810 |

|

1885-86 |

9742 |

|

1886-87 |

9187 |

|

1887-88 |

8936 |

|

1888-89 |

9801 |

|

Sources General Report

on Public Instruction in Bengal for 1884-85 to 1888-89. Calcutta: Government

of Bengal. |

|

Analysing student enrolment from 1884-85 to 1888-89 reveals a significant decrease over the subsequent three years following 1884-85. However, there was a slight increase noted in 1888-89 compared to the previous year, 1887-88. Specifically, in 1884-85, the student count stood at 10,810, whereas in 1888-89, it decreased to 9,801. Notably, until 1886-87, the Maldah Zillah School held the status of a third-division school. However, in 1887-88, it was promoted to the second division, indicating the school's growing importance in the educational landscape of the district during that period, attributable to the dedication of both teachers and students.

To provide a clearer understanding of educational statistics, the table below presents the public instruction records of education in Bengal spanning from 1891-92 to 1895-96.

Table 5

|

Table 5 The Number of Students in Maldah During 1891-92 to 1895-96 |

|||

|

Year |

Boys at Primary and

Secondary Schools |

Girls at Primary School |

The total Number of Students |

|

1891-92 |

10851 |

673 |

11524 |

|

1892-93 |

11015 |

698 |

11713 |

|

1893-94 |

10373 |

626 |

10999 |

|

1894-95 |

9853 |

497 |

10350 |

|

1895-96 |

12134 |

630 |

12764 |

|

Sources General Report

on Public Instruction in Bengal for 1891-92 to 1895-96. Calcutta: Government

of Bengal. |

|||

Upon closer examination of Public Instruction data from 1891-92 to 1895-96, a notable trend emerges regarding the inclusion of female students, primarily in primary education. In 1891-92, there were 673 female students in primary education, a number that increased slightly to 698 in 1892-93. However, in 1893-94, this figure decreased to 626, further declining to 497 in 1894-95, before experiencing a slight uptick to 630 in 1895-96. Meanwhile, the total number of students in the district increased from 11,524 in 1891-92 to 12,764 in 1895-96, indicating an overall improvement in the state of education during this period.

In 1897-98, the total number of boys in school, including both secondary and primary levels, was 12,972. Within the primary section, there were 66 upper primary schools with 2,967 students and 208 lower primary schools with 5,791 students. General Report on Public Instruction in Bengal for 1897-98 (1899). Subsequently, in the years 1901-02, 1902-03, 1903-04, and 1904-05, the total number of boys enrolled in school increased to 12,029, 12,802, 14,814, and 14,024 respectively. General Report on Public Instruction in Bengal for 1901-02 (1903). This consistent growth in student enrolment over the years underscores the effective spread of Western education in the district. Upon examining the period between 1911-12 to 1920-21 in terms of public instruction, further insights can be gleaned:

Table 6

|

Table 6 The Number of Schools and Students in Maldah During the Years 1911-12 to 1920-21 |

||

|

Year |

Total Schools |

Students |

|

1911-12 |

540 |

20,156 |

|

1912-13 |

565 |

20,609 |

|

1913-14 |

631 |

21,724 |

|

1914-15 |

617 |

22,139 |

|

1915-16 |

735 |

24,649 |

|

1916-17 |

719 |

24,783 |

|

1917-18 |

772 |

25,795 |

|

1918-19 |

784 |

25,186 |

|

1919-20 |

782 |

25,394 |

|

1920-21 |

799 |

26,812 |

|

Source Bengal District

Gazetteer: Malda District, Statistics, 1911-12 to 1920-21. Calcutta:

Government of Bengal. 1923. P. 26. |

||

In the year 1911-12, there were a total of 540 schools, encompassing both primary and secondary levels, accommodating 20,156 students. Subsequently, over the next few years, there was a notable increase in the number of schools with students. By the year 1920-21, this figure had surged to 799 schools, serving a student population of 26,812. This trend reflects a significant expansion in educational infrastructure and enrolment, indicating the continued growth and development of the education system in the district.

In addition to statistical data, analysing census reports offers valuable insights into the literacy rate of Maldah. It's important to note that the 1871 census doesn't include educational status, so our discussion on literacy rate will commence from the 1881 census:

Table 7

|

Table 7 The Literacy Rate of Maldah District |

|||||||

|

Year |

Population |

Literacy |

Percentage of literacy to

total population |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

||

|

1881 |

3,46,998 |

3,63,450 |

7,10,448 |

15,247 |

146 |

15,393 |

2.17% |

|

1891 |

3,99,917 |

4,15,002 |

8,14,919 |

22,984 |

335 |

23,319 |

2.86% |

|

1901 |

4,37,639 |

4,46,391 |

8,84,030 |

32,170 |

923 |

33,093 |

3.74% |

|

1911 |

4,98,547 |

5,05,612 |

10,04,159 |

44,243 |

1,661 |

45,904 |

4.57% |

|

1921 |

4,92,822 |

4,92,843 |

9,85,665 |

43,574 |

2,962 |

46,536 |

4.72% |

|

1931 |

5,27,305 |

5,26,461 |

10,53,766 |

30,094 |

3,174 |

33,268 |

3.16% |

|

1941 |

6,19,272 |

6,13,346 |

12,32,618 |

70,821 |

14,067 |

84,888 |

6.89% |

|

1951 |

88,810 |

86,858 |

1,75,668 |

13,832 |

3,738 |

17,570 |

10.00% |

|

Source Census of India

from 1881 to 1951. Calcutta: Government of Bengal. |

|||||||

According to the 1881 census, the total population of the Maldah district was 710,448, with 15,247 literate males and 146 literate females, totalling 15,393 literate individuals and yielding a literacy rate of 2.16 percent. Subsequently, in the 1891 census, the population increased to 814,919, and the number of literate individuals rose to 23,319. Despite the increase, the literacy rate only slightly improved to 2.86 percent. Over the first three decades of the 20th century, as per the census data from 1901, 1911, and 1921, both the population and the number of literate individuals continued to increase. Consequently, the literacy rate rose to 3.74 percent, 4.57 percent, and 4.72 percent, respectively. However, in the 1931 census, despite population growth, the number of literate individuals declined significantly, leading to a decrease in the district's literacy rate to 3.15 percent. Conversely, in the 1941 census, as the population continued to grow, so did the number of literate individuals, resulting in a notable increase in the literacy rate to 6.88 percent. Following India's partition, five police stations of the Maldah district became part of Pakistan, causing a decrease in both population and literate individuals. Nevertheless, the literacy rate surged to 10 percent due to these demographic shifts. This sequence of events illustrates the evolving landscape of education and literacy rates in the district over time.

2. Conclusion

The establishment of the Western education system in Maldah unfolded gradually over time. The initial steps toward this transformation were taken by the Christian missionary William Carey, who arrived in the village of Madnabati in Maldah around 1794 CE and established a school with 40 students. However, Carey eventually left Maldah for Srirampur, leading to the closure of his school. Subsequently, the British East India Company played a significant role in the spread of Western education through policies such as the Charter Act of 1813 CE and Macaulay Minutes, laying the groundwork for future developments. Although these policies did not immediately impact Maldah, they set the stage for the expansion of Western education. The official commencement of Western education in the district began with Wood's despatch policy, which led to the establishment of the first official school. This marked a turning point, as the demand for English-language proficiency grew due to employment opportunities within the British government. Consequently, the popularity of indigenous educational institutions waned, prompting a shift towards Western education in Maldah. Many primary schools with English as a compulsory subject emerged in the district, and under Sir George Campbell's scheme in 1872, efforts were made to integrate Western education into existing schools, supported by government grants. However, questions arose regarding the extent to which English could be taught in these schools. As traditional pathshalas faced closure, government intervention in the selection of pathshala gurus disrupted their traditions. Eventually, the government began appointing teachers in primary pathshalas, facilitating their transformation into schools following the Western education pattern and receiving grants. This transition from pathshalas to primary, upper primary, and ultimately secondary and higher schools accompanied an increase in student enrolment, leading to a lasting transformation in the educational landscape of the district and the significant development of Western education therein.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Basak, N. L. (1965). History of Vernacular Education in Bengal. Calcutta: Unpublished D.Phil thesis Calcutta University.

Carter, M. O. (2013). Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operation in the District of Malda 1928-1935. Siliguri: Reprinted by N.L. Publisher.

General Report on Public

Instruction in Bengal for 1897-98 (1899). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in Bengal for 1901-02 (1903). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in Bengal for 1902-03 (1904). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in Bengal for 1903-04 (1905). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in Bengal for 1904-05 (1906). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in the Lower Province of the Bengal Presidency for 1862-63 (1864). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

General Report on Public

Instruction in the Lower Province of the Bengal Presidency for 1868-69 (1870). Calcutta: Government of Bengal.

Ghosh, D. K. (2020). Maldaher Itihaser Dhara (A Course of the History of Malda from the

Pre-Vedic Age to the Independence Era). Kolkata:

Akshar Publication.

Ghosh, S. C. (1995). The History of Education in Modern India 1757-2012. Hyderabad: Orient BlackSwan.

Hamilton, D. F. (1833). A Geographical, Statistical, and Historical Description of the

District, or Zila, of Dinajpur, in the Province, or Soubah, of Bengal. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

Hunter, W. W. (1876). A Statistical Account of Bengal: District of

Maldah, Rangpur, and Dinajpur Vol. VII. London:

Trubner & Co.

Lambourn, G. (2004). Bengal District Gazetteers Malda. Siliguri:

National Library Publisher.

Sengupta, J. C. (1969). West Bengal District Gazetteers: Malda. Calcutta: West Bengal Govt. Press.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2024. All Rights Reserved.