THE USE OF CULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL HERITAGE IN EDUCATIONAL CONTEXTS BETWEEN SPACES, IDENTITIES, ATTITUDES, AND COGNITIVE WELL-BEING

Antonella Nuzzaci

1![]()

1 Full

Professor of Experimental Pedagogy, Department of Cognitive, Psychological,

Pedagogical Sciences and Cultural Studies, University of Messina, Messina,

Italy

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

explores some links between educational research, the use of cultural and

environmental heritage and education, where it is possible to combine

knowledge, disciplines, and skills to strengthen the cultural profile of the

school population, but also to bring about important changes in attitudes and

behavior. The world's cultural and environmental heritage, which collects the

traces of extraordinary but also tragic events in human history, can act as a

unifying force for peaceful coexistence for the whole of humanity, enabling

future citizens to participate in democratic debate and make informed choices

about the social challenges they face. It therefore contributes not only to

the development of knowledge, but also to the ability of children, young

people, and adults to understand contemporary problems by placing them in

human, social, environmental, historical, and cultural contexts that help

them to live. For cultural heritage to contribute to the recovery of

knowledge, researchers, teachers, and operators must be able to share a solid

research background that allows them to address the various issues relating

to the quality of the experiences of use carried out in school contexts, with

the aim of improving the learning processes of users. In fact, the cultural

and environmental resources of the territory can only be a real

methodological resource for improving cognitive well-being and the overall

quality of education at all levels if they are seen as useful tools for

different types of learning (cognitive, social, etc.) and not as general

educational tools. The paper therefore questions the use of cultural and

environmental heritage in education and its adequacy with respect to learning

conditions, pausing to consider also the role played by attitudes to

fruition, highlighting those elements and dimensions that can contribute to

redefining the relationship between education, goods, and environment, in the

idea of strengthening interpretative repertoires in educational contexts. |

|||

|

Received 04 March

2024 Accepted 06 April 2024 Published 30 April 2024 Corresponding Author Antonella

Nuzzaci, antonella.nuzzaci@unime.it DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v12.i4.2024.5587 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cultural Heritage Education, Scholastic

Enjoyment, Cultural and Environmental Goods, School, Learning |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Cultural and environmental heritage is not always

considered in its full educational potential and driving capacity to transform

the skills and attitudes of children, young people, and adults. We often talk

about it by emphasizing the role of those approaches that promote its

educational role, starting from the experiences lived by individuals in

contexts and environments that are also culturally, socially, and ecologically

complex, but without referring to the set of skills needed to decode and

interpret it. If competence is linked to the concept of situated knowledge and

the way in which it becomes meaningful, relevant and coherent for the learner,

and to the ability to mobilize different cognitive resources to cope with a

typology of conditions and problems, then the latter could also concern the

field of cultural heritage education, which has long been recognized as

important for the development of a community at territorial level and for

creating and restoring a sense of cultural belonging Nuzzaci (2018). However, this field,

precisely because of the complexity of the tasks, the different aspects and

knowledge involved from different sources and sectors (scientific, artistic,

archaeological, anthropological heritage, etc.), the innumerable families of skills

involved (visual-spatial and cognitive skills, solution strategies, etc.) and

the social mediation behaviors, is not an easy one. It requires the possession

of the widest possible range of high operational, cognitive, and strategic

skills, as well as collaborative forms of planning that must enable the

subjects to interact with the characteristics of the symbolic systems and

apparatuses of culture. In fact, complex implementation situations require a

creative approach to understanding and solving new problems and making

decisions in emerging areas, as well as the ability to assign meanings and

values to contexts that are changing so rapidly that they require constant

revision of meaning and updating of competence. To better explain these

aspects, some clarifications are indispensable. Learning about cultural

heritage in its many forms is increasingly recognized as a crucial approach to

reality, which, from an educational point of view, leads to the definition of

new strategies that can be successfully applied at any level of education, with

obvious benefits that include the development of a wide range of skills (from

those of the meta-cognitive domain and higher-order processes to relational and

social ones, from the improvement of knowledge to the motivation for knowledge

itself). At the same time, heritage research becomes a strategy when it ends up

establishing a link between methodology and explicit learning of the heritage,

strengthening the research-education-learning nexus in specific formal, informal,

and non-formal contexts. The encounter between cultural and environmental

heritage and educational research in Italy has followed its own path, which

over time has expressed an increasingly precise educational policy of the good,

coming to understand it as a fundamental tool of knowledge capable of

strengthening the cultural profiles of individuals. In this way, a synthesis

has been achieved between learning and the good, which inevitably implies the

capitalization of actions, cognitive, perceptive, social, and interpretative

processes of the meaning of fulfilment and its cultural interactions. In this

sense, the international context, especially in the 1990s, has marked a

profound development and reorientation of studies in this sector, making an adequate

collaboration between different disciplinary fields indispensable. This has led

to a series of important clarifications regarding the definition of heritage

education. In Italy, in the nineties, Laneve

(1992) gave life to the

conference organized in Foggia in 1990, a milestone in this sense, followed by

the most recent national and international experiences Nuzzaci (2011), Nuzzaci (2012a), Nuzzaci (2012b), affirming how the

teaching of cultural heritage is the study-production of appropriate

“mediations” Laneve (2000) aimed at encouraging

in every visitor-user, without distinction of age and/or social and cultural

status, the learning of cultural and environmental heritage, which implies the

acquisition of skills and the successful understanding Laneve

(1992) of what is used.

Today, this mediation also makes use of the use and experience of research

conducted in the field of digital communication, which is intrinsically rich in

semiotic modalities and resources to ensure a critical reflection on heritage Luigini & Panciroli (2018) and on the dynamics of

awareness, cognition and training of participants in digitally mediated

fruition processes with the idea of enhancing the effectiveness of the

educational experience and decoding of the asset.

We will look at this level here to understand who and what we are referring to when we talk about skills, spaces, identity, and education in this sector. In fact, we could refer to many things, namely the skills of the person who uses the asset, the skills of the person who creates the educational proposal, the skills of the teacher who uses the cultural asset for educational purposes, the skills of the operator, the mediator or the expert in the sector who acts as a mediator of cultural mediation in the territory. However, in order to try to answer these questions, it is necessary to start from a fundamental question concerning the good and its relationship with learning. The good, in all its forms, can become a dimension of learning, also in view of the profound changes that are affecting current alphabetic processes and that are gradually shifting literacy towards multiple and multimodal dimensions Nuzzaci (2011), Nuzzaci (2012), Anstey & Bull (2006). From the perspective of educational innovation, the good is in fact a source and a tool capable of promoting the development of more demanding educational actions, based on the knowledge and skills of those who, in different capacities, work between training and territory in the various educational and cultural institutions. It contributes to the qualification of the educational intervention by directing the “acting” towards the exercise of conscious and responsible choices, characterized by an educational intentionality capable of influencing the interpretative repertoire of those who use the asset for cognitive purposes.

The importance of possessing a grammar, a vocabulary, and

appropriate cultural tools, both theoretical and technical, which enable

everyone (child, adolescent, and adult) to enjoy the cultural and environmental

heritage in a conscious and responsible way, requires careful skills of

analysis and cultural educational planning. It is the same tool that enables

individuals to understand how certain changes have altered the conditions of

access to cultural heritage, its specific character, and its plurality, in line

with the changes that have affected society as a whole, in particular the

ongoing process of cultural democratization. And even if there has not always

been a real tradition in this sense in Italy, that is to say, not in all

periods have appropriate conditions and coherent educational policies of the

good been achieved, we must not forget that recently we are witnessing a

radical change in the situation, born of the desire to create a favorable terrain for the encounter between education and

cultural heritage. Suffice it to say that since Law no. 107 of 13 July 2015 -

known as the “Good Schools Law” - which came into force on 16.07.2015, and the

MIUR-MIBACT Memorandum of Understanding of May 2014, new opportunities for

cooperation and planning between education and heritage have been offered to

education, giving this encounter the character and history required from time

to time. In fact, it is

necessary to recognise that the school has played a fundamental role in

defining a new quality of democratic use of cultural heritage and in civil and

cultural development, effectively activating forms of observation,

identification, recognition, interpretation, and knowledge. and appropriation,

as well as the promotion and protection of heritage, especially the local

heritage closest to the pupils' experience.

The specialized nature of the good, in fact, contributes

decisively to making it a particularly useful “means” at the educational and

didactic level, at least in its immediately usable and perceptible aspects,

even if when we speak of the good, we think of an “objectivity” that often

leads to the misconception that it produces learning in

itself or, rather, that it leads to quick and easy acquisition. The

danger we face today is the persistent misunderstanding of the function of the

good, rather than the character of its structures, configurations, and history.

However, this is a risk that cannot be avoided if we want to tackle the problem

of education for the good properly. On the other hand, cultural heritage,

precisely because of the diversity of its forms, requires solid intellectual,

methodological, linguistic, etc. skills, combined with attitudes and behaviors that enable the user to correctly decode the

messages it conveys, even if it is equally undeniable that solid skills are

also needed by those who build the cultural message “on and around the good”,

in order to correctly decode the meanings of which the good is the bearer, in

an effort to make this message understandable to everyone. From the point of

view of knowledge production, this is the complex field of cultural heritage

education, which considers fruitful practices in their plurality, heterogeneity

and multi-referentiality, stimulating a particularly rich reflection also on

other aspects that concern reality, education, the present, the past and the

future, in the more general sense of human history. In today's world, which faces the challenge of

uniting peoples for peaceful coexistence, world cultural heritage, which

collects the traces of extraordinary but also tragic events in human history,

can serve as a unifying force for humanity Timmermans et al. (2015) and to help them overcome those

forms of "existential displacement" that occur after major disasters

or pandemics (2022) and that affect people's lives, their livelihoods and the

socio-cultural fabric of society. Enabling future citizens to participate in

democratic debate and to make informed choices about social challenges

therefore serves not only to build their knowledge, but also to make them more

capable of interpreting contemporary problems and emerging conflicts, both near

and far, by placing them in an interpretive context that is at once human,

social, environmental, historical, and cultural.

In the face of this plurality of culture, which is constantly diversifying and varying its forms, just as it is increasingly differentiating the ways in which it is used, speaking of education for the “good” becomes essential to understand the multiplicity of transformations taking place in this culture today. In fact, when we study heritage education, we notice that, in general, the “methodological” legitimacy is often affirmed in a practical sense, i.e. not linked to a substantiality of pedagogical research, but to that of “doing”, which is often not supported by an effective empirical verification of what is promoted and done. This type of explanation implies a radical reform of the formative culture of the good, in a field where the latter can be said to be an instrument capable of producing real “skills in the user”. This is especially true at a time when the depth of educational interventions, both inside and outside the school, has increased greatly, in a progressive process of empowerment of the local community, which is called to act with a view to “educational continuity and contiguity”, but still in the total absence of its own theoretical paradigms, where the different knowledge and the different scientific disciplines intersect, offering spaces of intersection for concrete training opportunities. What emerges is a completely paradoxical situation in which we want more education in the good and, at the same time, less of it, that is, on the one hand we want the good to make us learn and, on the other, we want it not to do so much. The ideal often pursued is that of a good that educates without instructing, which is a tolerated inconsistency that goes unnoticed.

2. EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FRUITION

But in what sense does the good educate, and can it be used effectively in formation? It depends on how it is “practiced” and used, and on the idea of education that guides its realization. If pedagogy has long pointed out that the path of knowledge passes through the recognition of the centrality of research, analysis and enjoyment for the problem encountered and the identification of solutions for its explanation, it will be the task of education to the good to make the experience of fruition enjoyable from an emotional and cultural point of view, providing the interpretive keys to make it meaningful from the point of view of learning and creating the disposition to repeat it. In this case, research is a key element in the approach to new situations, problems, objects and fields of work, especially when it is proposed to address them with a vision that is not only applicable or of the transfer of knowledge and models, but by setting up experimental interventions with a view to exploration and analysis, to the construction of innovative representations of the problems for their better management or the solution of the phenomena studied Nuzzaci (2012c). Whoever learns to solve problems, to identify their limits and to remedy them, participates in culture, because this is his creation and is communicated and supported by precise cultural codes Bruner (1988). Very often, when we speak of education for the good, we refer in a general way to the activity carried out, forgetting that, to achieve this objective, it is necessary to define appropriately “rationalized” proposals that know how to interpret it correctly. From an operational point of view, this objective must lead those working in the sector to consider educational initiatives and interventions as a means of promoting the acquisition of specific skills, capable of being grafted onto a complex training that makes available the use of precise cognitive and affective tools and is the basis of the ability to correctly enjoy cultural heritage. It is therefore interesting to consider how to integrate the use of the good within a continuum of knowledge, repertoires, and meanings, based on the (pre)disposition of positive access conditions for the construction of meaningful experiences and learning (affective, cognitive, and motor). For this reason, it's essential that the educational activity is entrusted to personnel with adequate pedagogical skills Nuzzaci (2008), in order to guarantee everyone's right to fulfilment, an objective shared by the school and other cultural institutions, which must be based on interventions shared both by those working within the training and those working within the cultural institutions, in a mix of skills that tend to reinforce each other. Thus, if it is clear that “cultural proposals” should be considered as the real meaning of heritage education, it is equally clear that they must be formulated based on the characteristics of the type (“typicality”) of heritage to which they refer, the objectives identified, the specificity of the spaces and contexts concerned, etc. These proposals must include events and activities that can reach the types of recipients to whom they are addressed, and of activating appropriate interventions and strategies by preparing “opportunities” and “situations” that are truly functional for learning. It is therefore essential that the events, actions, and activities are the result of intensive research work aimed at methodological consolidation and providing for a substantial integration and interrelationship between different disciplines and fields, with the aim of bringing together expert skills working together on the idea of the good as a place and space for the training of skills, especially transversal skills. However, beyond the proclamations, the creative dimension of heritage education is not at all common, either in the practices of implementation and daily educational practice, or even in the practices of pedagogical research. This problem is undoubtedly due to the lack of resources, but it is also undoubtedly due to a misconception of heritage and its social function. It is therefore clear that such an articulated process of cultural development requires a rethinking both of the very concept of heritage education (which has never been specified in its fundamental aspects and characteristics and has never been considered as a moment of verification of one's own actions) and of the re-qualification of those working in local cultural institutions (who have almost never taken the trouble to study the effectiveness of the cultural proposals developed in terms of learning, the impact on the learning of the target group and what lies in the specificity of their proposal compared to other forms of education). From what has been said so far, we could conclude that the constant flow of information that would be necessary in the management of Education for the Good remains very fragile, and that it derives from the need to keep the entire management of the cultural proposal in a state of constant control. There is an urgent need to reflect on the role that evaluation can play in the process of education for the good, as a tool capable of making operators take the most appropriate decisions regarding the process from time to time, and possibly assessing its validity; this is equivalent to considering the educational choices modifiable and shifting the greater weight of adaptation to the educational action, as well as taking note of the differences that exist between the different users and acquiring useful elements for the subsequent programming of the territorial cultural offer. Over the years, it has become increasingly clear that there is a close link between the possibility of introducing changes that affect the quality of the cultural proposal and the availability of analytical information on its characteristics. The flow of information is therefore an indispensable condition for the management of educational action, at whatever level it is carried out, without which it is unlikely that effective decisions can be taken, for example to redirect the proposal along innovative lines. The most important consequence of this approach is that evaluation no longer overlaps with “already existing conditions” but becomes a principle for regulating activities and for making informed choices. It is therefore necessary to develop educational proposals based on solid research, moving away from an idea of the culture of the good centered on intuition and the subjectivity of choices, and promoting a culture oriented towards the analysis and objectification of problems, the explication of hypotheses, etc. This will make it possible to overcome any suspicion of the attempt to introduce elements of rationalization in the organization of the work of educating the cultural heritage and to reject the recurrent objection that, in enjoying the good, one does not become a “school” and that, therefore, one speaks of education but does not do education, confusing the level of learning with the plan of education.

Research

is here not only a necessary operational moment, but it becomes a way of

conceiving education for the good, centred on the learner who learns, on his

previous experiences and knowledge, on his possibilities to deepen, extend,

reorganise, build his own knowledge. But the problem becomes even more

complicated when we consider that multiple cultural forms represent many ways

of looking at the world and how it can be presented, used, and understood by

different audiences. Indeed, commodities reflect not only a particular ontology

(a view of the nature of the physical world we inhabit) but also a particular

epistemology (a view of how knowledge is acquired), and this implicitly

determines the way in which individuals learn. More reason, therefore, that the

improvement of the quality of education must be based on the study of the

relationships, interactions, flows, functional regulation, and dynamics of the

articulation of the components that act in the educational process that

concerns goods.

This

means that those who mediate and use the good for educational purposes must be

able to work together to cope with the “hyper-complexity” that dominates the

cultural and territorial universe, in order not to run the risk of producing,

in the first case, theoretical schemes that are ineffective in practice, or, in

the second case, practices that are devoid of certainties. On the other hand,

if it is true that those who are concerned with “education for goods” must

strive to put into practice increasingly effective forms of planning, it is

equally true that those who are primarily concerned with “research on education

for goods” cannot neglect the relationships that exist between disciplines,

sources, territories, and specific learning contexts. It is precisely in

culture, understood as the context of the production and interpretation of

meaning, that spaces open that are large enough to contain a great variety of

cultural, social, and artistic forms, including both material and immaterial

goods. It is then evident that culture is not a genre, but that all genres are

potentially cultural” Parancandolo (1997), 162.

This

obliges us to clarify the relationship that exists between the identities of

the good (typologies) and the education of goods, as well as between education

and didactics, between general didactics and the didactics of the discipline

and of “knowing how to communicate, mediate and teach”. In this sense, it is

also necessary to understand the real impact of the user experience on the

individual who carries out a specific programme or educational path, in terms

of actions that favour the acquisition of knowledge, the understanding of

concepts and any positive attitude towards the good or territory. Educational

research must address some of these important issues if it is to pursue precise

educational objectives and participate more intensively than in the past in the

education of the community, also thanks to the partnership with schools and

local institutions. If, on the one hand, the improvement of the pedagogical

quality of the asset is to be achieved through the recognition of “strong

skills”, on the other hand, it is necessary to provide teachers, sector

operators, mediators, etc. with the means that will enable them to commit

themselves in this direction, avoiding that their “undeclared work” is

necessarily dispersed in occasional activities and without a systemic approach.

These needs are now widely shared by educators, trainers, operators in the

sector, researchers, teachers, and administrators. But very little is being

done to respond to them in a precise and concrete way.

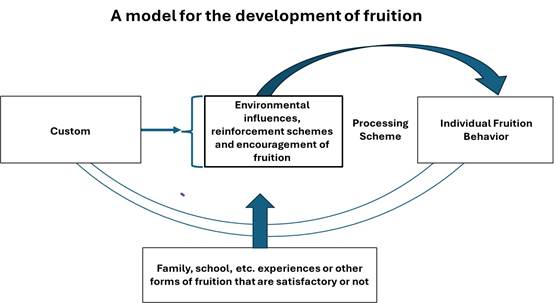

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Fruition and Behavior |

3. BUILD A POSITIVE ATTITUDE TO FRUITION TO LEARN HOW TO “USE” THE GOOD TO RE-ESTABLISH IDENTITY AND ACTIVELY EXERCISE CITIZENSHIP

Cultural

heritage, both tangible and intangible, as an open concept, refers to culture

as a dynamic process and reflects life in all its aspects. It affirms in

tangible and intangible ways that every person, group, or social practice is a

cultural product. Environmental and landscape heritage, as a set of natural

beauties and artistic-historical-cultural heritage in its complexity,

recognises the preservation of historical and artistic heritage to safeguard

civilisation, customs, and traditions, in essence the historical memory of a

community, and to protect the environment built by man over time. Here,

landscape is also recognised as having a psychological function Lingiardi (2017), in addition to its

cultural, ecological, environmental, and social functions, emphasized in the

European Landscape Convention as "contributing to human well-being and

satisfaction and to the consolidation of European cultural, ecological,

environmental and social identity". In this sense, the European Convention

on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society of 27 October 2005, or the Faro

Convention, opens a concept of heritage as a useful source both for human

development, fulfilling specific educational functions and implying the

enhancement of cultural diversity and the promotion of intercultural dialogue,

and as a model of economic development based on the principles of sustainable

use of resources.

In this sense, it is also necessary to read the ample space devoted to heritage education in Italy, which, with great effort, has initiated interdisciplinary scientific and methodological studies so that every citizen can freely participate in the cultural life of the community, enjoy the goods, and participate in scientific cultural progress and its benefits. This is also thanks to the fact that Italy has a recognised cultural influence in the world, linked both to the attraction of its heritage and to the ability to develop new forms of knowledge and skills, starting from the exchange of human values, unique and exceptional testimonies of cultural traditions, extraordinary examples of settlements and types of buildings of extreme value, architectural and technological ensembles and new landscapes representing different phases of history UNESCO (2011), UNESCO (2023), UNESCO (1972).

One's own

previous experience and that of other human beings, in the form of culture,

comes into play in almost every event of existence. Each specific culture

provides a kind of blueprint for all life's activities

Kluckohn (1960). There is a relationship between

social and cultural practices and the construction of identities Levi-Strauss (1980), which have many relationships with

history, heritage, culture, language, and consciousness, as well as a complex

of other characteristics. In this sense, personal identity and society are

complementary elements in the construction of reality Mead (1966). Identity does not belong

exclusively to the individual, but is understood as a structure of social

order, the construction of which is the result of a self-regulating process

that relates representations of self to reality.

Consequently,

the ongoing practices of human beings in the context of groups, through which

the participants construct with their lives the character and identity of a

particular community and the specific pattern of behaviour that distinguishes

it from all others, lead to an understanding of culture essentially as a

construct describing the totality of beliefs, behaviours, knowledge, sanctions,

values and goals that characterise people's way of life: what they have, do and

think Herskovitz (1948), p. 625. However, the “possession”

of culture presupposes that the possessor is aware of his “knowledge” and that,

to really “master” it, he not only has an idea of it, but also lives it and is

consciously “imbued” with it.

It is

obvious that, in this perspective, the current trend is above all to study one

of the central dimensions of heritage education, namely that of active

citizenship. Indeed, cultural, and environmental heritage education is a tool

for lifelong learning and a space for exercising civil, cultural, and social

rights, the “subtle” ones Bobbio (2007). Attitudes towards the good are

generally accompanied by strong emotional tones of attraction or repulsion;

negative and persistent attitudes are almost always linked to unfavourable

experiences, even at a young age. And this aspect is more interesting when we

consider that attitudes towards the good, school, and non-school experience,

the process of acquisition are all variables that influence each other. It is a

widespread belief that the good is experienced to a very different extent by

different users, mainly because of the differences in prerequisites and

abilities between subjects. The presence or absence of certain prerequisites

for reading or decoding the good facilitates or hinders its understanding,

especially within an increasing complexity that sees the cultural heritage of a

community in constant movement and change. Precisely from the observation that

there is a diachronic and synchronic fluctuation of the good, it is essential

to equip oneself with a solid cultural substratum capable of coping with the

changes that occur within cultural systems, where moments of formation

constitute an essential condition for attending to the growing participation

and awareness of new scenarios in the territorial contexts in which one finds

oneself living and working. The goods recall the concrete possibility of

rethinking the spaces of education, creating and re-creating contexts of

sharing for a new sense of citizenship. In thinking about the role played by

forms of learning that take place outside the school, we must reflect on the

multiplication of places and opportunities for an education that today seems to

be increasingly articulated and extensive. This diversity calls for a high

degree of differentiation in pedagogical methods, both in terms of pathways and

in terms of the tools and techniques used, as well as in terms of challenging

forms of cultural literacy that are not always, or still too little, pursued by

schools. However, it must be remembered that it is precisely from the richness

of the contributions of recent years that new bodies have emerged that seek to

answer questions related to the debate on important concepts, on what “user

skills” would be necessary as opposed to “sector skills”, and on what kind of “educational

communication” is more appropriate to ensure that heritage becomes a space and

a cognitive environment Nuzzaci (2011). Identifying strategies for

approaching the process of learning and training for the good therefore means

bringing into play the relationships between the construction of knowledge and

the construction of attitudes towards fruition, which are based on previous

experiences and exquisite individual skills, including soft skills. Working on

the reading of cultural objects (natural, artistic, etc.) and on all the

obstacles that prevent their correct use (symbolic, cultural, interpretative,

contextual, etc.) means building an “intentionality of seeing” that prepares

and integrates understanding. The good thus becomes a narrative plot, the

telling of a story that users can read, interpret, and discover in new “writings”

(new scripts), as well as “reciting” them. This allows us to emphasise the

importance that, if properly mediated, the pleasure associated with the

experience of fruition, the familiarisation with the cultural, social, and

territorial space and possible learning reinvestments can assume, with a view

to creating a favourable availability for the enjoyment of cultural heritage

and transforming the child, the young person, the adult into a “consumer and

frequent user” of goods. These considerations seem necessary to work on a

different representation of heritage and on its concrete possibility to

contribute to the “formation” of individuals, that is, to positively influence

their cultural elaborations. It is therefore necessary to translate into

concrete objectives the ambitious goal of “building” positive attitudes, and

thus making the freedom to enjoy the good effective. It is well known that attitudes are linked to

aspects of the individual's personality, both because they depend on previous

experience and because they concern beliefs, emotions, values, etc., and are

characterised by a “tendency to act”. The positive attitude towards achievement

is linked to the value that the individual assigns to it, that is, the value

that it occupies in the hierarchy of values of a person. If the value

attributed to use is high, it is likely that the frequency of use of the asset

will also be high. However, for this attitude to be stable, it must be based on

pedagogical skills capable of creating, modifying, and maintaining it, thus

ensuring the correct use of the asset by the user, as well as his habit of

visiting it. Specifically, it involves:

·

create

an affective disposition conducive to the encounter with the cultural heritage;

·

make

the encounter with the cultural asset positive so that the pupils develop

pleasant perceptions of it and of themselves in relation to the asset;

·

show

that knowing the good is useful and that great cognitive advantages can be

derived from such experience;

·

meet

individual needs;

·

tailoring

education and training to the good of the students;

·

make

the cognitive impact of the good profitable;

·

consolidate

and sediment experiences.

In fact,

it is well known that a positive attitude becomes more positive and a negative

attitude more negative when it is linked to other attitudes and other

characteristics of the individual, for the same reason that a good result

obtained in one area can influence the positive attitude and vice versa, with

repercussions on subsequent experiences. It is therefore intuitive to conclude

that attitudes are shaped by the information to which the individual is

exposed, and that the individual tends to use it in ways that reinforce

pre-existing behaviours and attitudes. It follows that educational

interventions can bring about stable changes in people who already have their

own attitudes or in those who do not have them at all. Referring all this back

to the various educational institutions involved (schools, playgrounds,

libraries, museums, etc.), we can say that they are able to reinforce

previously assumed attitudes of fruition or to create new ones, if they use the

asset in a way that is consciously functional for the educational experience.

These are all elements that can help to identify

innovative methods and tools to elaborate, internalize and build and implement

new cultural objectives in formation. In its spatio-temporal

continuity, the Italian urban heritage can become a dimension of learning,

especially when it is interpreted as a space of cultural intersection and trait

d'union between testimonies and cultures from all

over the world. All this starts from a tradition of educational research that

thinks of heritage in properly interdisciplinary and multidimensional terms

that the different disciplines use to interact with each other in a highly

productive cultural exchange. Usually,

when referring to learning contexts, most of the spaces and environments of the

territory, including urban ones, are not considered from the point of view of

their critical interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary and multicultural

potential, because environmental education and the territory are always thought

above all in relation to the depletion of natural resources and environmental

degradation Gough & Gough (2010), the deep general concern about the

deterioration and devastation of places and the poor relationship between human

beings and their environment, biophysical, social and cultural. Although common

visions are linked to the importance of caring for and relating to the

environment and territory, too often there is a certain disregard for the

needs, cultures, values, and symbolic repertoires of the different communities.

Research Hazler (2012), Okuyucu & Somuncu

(2012), Karadeniz et al. (2018) showed how experience with it

(whether negative or positive) with urban heritage can influence perceptions,

representations, and learning, shaping individuals' interpretation of reality. By

drawing on the relationships between perception/learning/emotion of

individuals, education could succeed in developing analytical frameworks

capable of incorporating additional elements aimed at enhancing the cognitive

and interpretative possibilities of reality by children, adolescents, and

adults. This is because cultural and environmental heritages can redesign the

representations of meanings and symbols, taking on the role of real cultural

supports, capable of providing users with denotative and connotative elements

essential for recognizing and managing symbolic systems and strengthening

alphabetic processes. This is because the nature of urban and environmental

heritage is closely related to identity and symbolic processes, fueling complex semiotic functions.

4. CONCLUSION

The good can make a valid contribution to education if it makes the educational act, rather than the educational discourse, the object of analysis, in order to identify, define and translate pedagogical principles into activities. The way in which the culture of the good and the learning of knowledge in context are defined in Italy is essential to achieve a better specification of the theoretical framework and the possibilities offered by the development of a process of learning the good, conceived as a space “open to the whole community”. This calls into question pedagogical research, which, in turn, opens every space for “freedom of understanding”, pursuing the path of knowledge of which heritage education is a part. In this sense, the encounter between pedagogy, research and education on cultural and environmental heritage implies forms of planning aimed at supporting the learning of the school population, at all levels of education, and of all individuals (children, young people and adults), through the co-design and management of precise environments and educational spaces, increasing the quality of fruition and the adequacy of acquisition processes of various kinds (cognitive, social, relational, etc.). From this point of view of interpretation, cultural and environmental heritage can only become accessible to all if the alphabet through which it is expressed is understood, so that it ceases to be a “monument” to be transformed into a real educational need aimed at strengthening the interpretive repertoire of individuals in educational contexts to improve their “cognitive well-being” and their inclusion processes.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abbott, C. (2001). ICT: Changing Education. Cornwall: Routledge.

Anstey, M. (2002). "It's Not All Black and White": Postmodern Picture Books and New Literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(6), 444-457. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.45.6.1

Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2006). Teaching and Learning Multiliteracies: Changing Times, Changing Literacies. Newark, NJ: International Reading Association.

Bobbio, A. (2007). I diritti sottili dei bambini. Roma: Armando.

Bruner, J. (1988). La mente a più dimensioni. Bari: Laterza.

Cahill, C. (2007a). The Personal is Political: Developing New Subjectivities Through Participatory Action Research. Gender, Place and Culture, 14(3), 267-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690701324904

Cahill, C. (2009b). Beyond "us" and "Them": Community-Based Participatory Action Research a Politics of Engagement. In M. Diener & H. Liese (Eds.), Finding Meaning in Civically Engaged Scholarship: Personal Journeys, Professional Experiences, 47-58. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., & Elmquist, M. (2016). Framing Design Thinking: The Concept in Idea and Enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 38-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12153

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. Melbourne: Macmillan Publishers.

Diener, M., & H. Liese, H. (2009). Finding Meaning in Civically Engaged Scholarship: Personal Journeys, Professional Experiences. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Ginzarly, C. Houbart & J. Teller (2018). The Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Urban Management: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(16), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1552615

Gough, N., & Gough, A. (2010). Environmental Education. In C. A. Kridel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies, 1, 339-343. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hazler, V. (2012). Perception of Culturel Heritage and Monument Protection. Traditiones, 41(2), 123-134.

Herskovitz, M. J. (1948). Man and His Work. New York: Alfred A.

Karadeniz, B. C., Sari, S., & Özdemir, N. (2018). Ordu University Students' Cultural Heritage Perceptions and their awareness. 3. Uluslararası Felsefe, Eğitim, Sanat ve Bilim Tarihi Sempozyumu, Giresun.

Kluckohn, C. (1960). Mirror for Man. New York and Toronto: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Laneve, C. (1992). La didattica museale verso un significato forte. In La Didattica museale, 36-41., Atti del Convegno di Foggia, Museo Civico, 28-31 marzo 1990. Bari: Edipuglia.

Laneve, C. (2000). Pedagogia e didattica dei beni culturali: viaggio nella memoria e nell'arte. Brescia: La Scuola.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1980). L'identità. Palermo: Sellerio.

Lingiardi, V. (2017). Mindscapes. Psiche nel paesaggio. Milano: Raffaele Cortina.

Luigini, A., & Panciroli, C. (2018). Ambienti Digitali per l'educazione all'arte e al patrimonio. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Mead, G. H. (1966). Mente, sé e Società (1934). Firenze: Giunti Barbera.

Nuzzaci, A. (2011). Patrimoni Culturali, Educazioni, Territori: verso un'idea di Multiliteracy. Brescia-Lecce: Pensa MultiMedia Editore s.r.l.

Nuzzaci, A. (2006). Musei, pubblici e didattiche. La didattica museale tra sperimentalismo, modelli teorici e proposte operative. Cosenza: Lionello Giordano.

Nuzzaci, A. (2008). Quali Competenze Pedagogiche Per la Didattica Museale? In G. Molteni (a cura di), Il museo delle Esperienze Educative, 83-100. Pisa: Pacini.

Nuzzaci, A. (2012a). La didattica museale tra pedagogical literacy, heritage literacy e multiliteracies. Costruire il profilo del letterato del 21° secolo. Lecce-Brescia: Pensa MultiMedia Editore s.r.l.

Nuzzaci, A. (2012b). The Technological Good' in the Multiliteracies Processes of Teachers and Students. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 3(3), 12-26. https://doi.org/10.4018/jdldc.2012070102

Nuzzaci, A. (2012c). Experimentalism in the Field of Museum Education: Empirical Research on the School-Museum Relationship. Education, Special Issue, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.edu.20120001.06

Nuzzaci, A. (2016). I beni culturali tra competenze, identità e atteggiamento verso la fruizione: il ruolo della ricerca educativa. In T. Aja, L. Calandra & A. Vaccarelli (a cura di), L'educazione outdoor: territorio, cittadinanza, identità plurali fuori dalle aule scolastiche, 178-193. Lecce-Brescia: Pensa MultiMedia Editore s.r.l.

Nuzzaci, A. (2018). Patrimoni locali, identità e linguaggi: educare "ai e con i" beni culturali e ambientali in aree ad elevata fragilità. In S. Mariantoni & A. Vaccarelli, Individui, comunità e istituzioni in emergenza. Intervento psico-socio-pedagogico e lavoro di rete nelle situazioni di catastrofe, 213-229. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Nuzzaci, A. (2022). 'Existential and identity displacement' in catastrophic events. Teacher training: skills and strategies for coping. In L. Patrizio Gunning & P. Rizzi (Eds.), Invisible Reconstruction. Cross-disciplinary responses to natural, biological and man-made disasters, 313-327. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2kg15nv.28

Nuzzaci, A., & Rizzi, P. (2021). Cittadinanza europea, Costituzione e Diritti: l'educazione come strumento di democrazia / European Citizenship, Constitution and Rights: Education as an Instrument of Democracy. Brescia-Lecce: Pensa MultiMedia s.r.l.

Okuyucu, A., & Somuncu, M. (2012). Determination of local People's Perceptions and Attitudes Protection of Cultural Heritage and Use of Tourism Purpose: Case of Centre of Osmaneli District. Ankara Üniversitesi Çevrebilimleri Dergisi, 4(1), 37-51.

Parancandolo, R. (1997). Opinione pubblica e opinione di massa. In J. Jacobelli, Scienza e informazione (pp. 162-166). Bari, Laterza.

Rhoten, D., & Pfirman, S. (2007). Women in Interdisciplinary Science: Exploring Preferences and Consequences. Research Policy, 36(1), 56-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.08.001

Timmermans, D., Guerin, U., Rey da Silva, A. (2015). Heritage for Peace and Reconciliation Safeguarding the Underwater Cultural Heritage of the First World War. Manual for Teachers. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (1972). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2011). Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions.

UNESCO (2023). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris. UNESCO.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2024. All Rights Reserved.