Student loans: an alternative to finance studies used by higher education students in Mozambique

José Amilton Joaquim 1![]()

![]() ,

Luísa Cerdeira 2

,

Luísa Cerdeira 2![]()

![]() , Eugénia Flora Rosa Cossa 3

, Eugénia Flora Rosa Cossa 3![]()

![]()

1 PhD

in Economic and Organizational Sociology, Lecturer in the Category of Assistant

at the Faculty of Education at Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique

2 PhD

in Educational Sciences, Retired Associate Professor at the Institute of

Education of the University of Lisbon, Lisbon

3 PhD in Educational Sciences, Associate Professor at the Faculty of

Education at Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Student loans

as an alternative to social support for students are a contribution of

economic theory to the financing of higher education. This study seeks to

reflect on loans as a social support policy used by several countries for

higher education students and to show the reality of loans made by higher

education students in Mozambique. Data were collected from a questionnaire

applied to higher education students, for a theoretical sample of 508 and an

empirical sample of 607 students in the province of Gaza, in February and

March 2018. Results reveal that student loans are not a social support policy

co-financed by the Mozambican State, as in other contexts. Students have

turned either to formal institutions, such as commercial and microfinance

banks or to informal associations, called Xitique, to cover the costs of

their studies. This allows concluding that, despite the challenges, loans can

be a positive alternative for the government in the diversification of social

support to students, which will allow better access to higher education,

provided that they are introduced taking into account students/families’

socioeconomic conditions and with efficient mechanisms or systems that help

control borrowers’ reimbursements and disbursements. |

|||

|

Received 22 September 2023 Accepted 23 October

2023 Published 06 November 2023 Corresponding Author José

Amilton Joaquim, jhamylton@yahoo.com.br DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v11.i10.2023.5350 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Higher Education Students’ Loans, Higher

Education Students’ Social Support, Accessibility and Equity in Higher

Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The 1960s and 1970s are considered the

golden age of higher education in Africa, and the demand for this level of

education by students and families tends to increase, with a majority of

families holding higher education training perceived as an opportunity to

counter social mobility.

In Mozambique, from the 2000s onwards,

there was a significant increase in the number of students, from 10,906 in 2001

to 200,649 in 2017. According to statistical data from the National Directorate of Higher

Education (2021), the country currently

has 213,930 higher education students, of which 117,340 are male and 96,590 are

female. The highest number of students is enrolled in public higher education

(128,428), and the remainder (85,502) is enrolled in private higher education.

One of the great challenges of higher

education at the global level is related to financing issues, which tend to be

much more critical in developing countries due to the various priorities in

different sectors and social domains.

The financing modalities for higher

education, either directly from the State budget or indirectly from the

diversification of social support, reveal the commitment of different

governments as a way of guaranteeing access, equity and quality training for

their fellow citizens.

Given this reality, the concern of almost

all researchers in the field of higher education funding is related to social

justice based on equity and accessibility.

So as to diversify student social

support, besides scholarships, which is a very common social support, several

countries have used loan policies to guarantee a wider range of support for

student financing and ensure more equity and accessibility.

Hauptman (2007) states that the

combination of non-reimbursable support (grants or scholarships), which rely on

the financial needs of the student and his/her family, is generally based on

criteria of merit rather than need, while reimbursable support (including a

wide range of student loan agreements) is a key issue for policymakers in

determining the government’s role in helping students and families pay higher

education expenses.

This tendency to combine reimbursable and

non-reimbursable social support emerges, according to Barr (2005), from the contribution

of economic theory, inasmuch that most students are not able to pay for higher

education expenses, which creates the conditions to solve this via the

well-planned student loans, making, in this case, according to Hauptman (2007), a

mix of scholarships, loans and work-study.

This study seeks to reflect on the

student loan theories, which are a practice in various contexts at the global

level as one of the alternatives of social support to students subsidized by

the State, without neglecting the groups pro and against the loan in higher

education financing. It also seeks to put forth, based on empirical data, how

loans to pay for studies in higher education take place in the Mozambican

context, even though it is not one of the State’s social support policies for

the case of Mozambican students, specifically in the province of Gaza.

2. Methodology

This study was carried out

in the province of Gaza, Mozambique. This province currently has seven higher

education institutions (HEIs), which are 13% of the total number of HEIs in

Mozambique. In 2018, when the empirical data were collected, the province of

Gaza had 10 HEIs, of which three were public and seven were private. The HEIs

in the province of Gaza are binary (universities and polytechnics) and have

different funding policies, even in public HEIs. The empirical research was

carried out in February and March 2018, and eight HEIs, three public and five

private, participated. A questionnaire survey was used to obtain data from

students about the sources of financing, with the loan being one of the

sources. These data were complemented with theoretical information, which

enable understanding the types of loans practised in Mozambique by students

vis-a-vis student loans practised in other contexts that rely on State support.

The questionnaire survey model used in this study has been used in

international studies on cost-sharing, such as the CESTES project – Cost of the

Higher Education Student in Portugal (CESTES I in 2010/11; CESTES II in

2015/2016). The survey model underwent an a priori validation process, which

consisted of applying it to 30 public and private higher education students in

the province of Maputo to test whether the survey model was in good condition

for implementation in the Mozambican context.

Based on the stratified

probability sampling method, 607 higher education students were surveyed, the

largest number (83%) belonging to the Gaza province, where the field research

was carried out. The students covered by the study come from the three regions

of the country, North, Centre and South. Of the students surveyed in the

sample, 53.8% (the highest percentage) are female, whereas 46.2% are male.

Regarding the students’ age, most students (71.7%) are between 21 and 30 years

old, while 28.3% of students are over 30 years old.

3. Literature review

3.1. Student loans: An alternative to social support for higher education students

In his

notes on Higher Education Financing in the Medieval Period, Usher (2017) sustains that the history of the tradition of

providing support to needy students through scholarships is as old as the

universities themselves. The concept of lending money to students, both

commercially and in the form of grant rates, is also a very old practice.

In the 13th

century, when student loans were made by “local sharks”, they were considered

predatory to the point that King Henry III lowered the interest on these loans.

To keep students away from such lenders, Oxford encouraged the creation of

donations whose proceeds could be used to provide interest-free loans to

students.

However, it

is important to mention that several authors, such as Chapman (2005), Teixeira

(2006), and Cerdeira

(2008), have ascribed this idea of student loans to the

economist Milton Friedman as the pioneer of issues related to them.

For Teixeira

(2006), Friedman, through the effective rhetoric of his

“Capitalism and Liberty” (1962), launched the contemporary debate on the role

of markets and governments in higher education.

As can be

seen in the writings of the economist Friedman

(1955), For vocational education, the

government, this time however the central government, might likewise deal

directly with the individual seeking such education. If it did so, it would

make funds available to him to finance his education, not as a subsidy but as

“equity” capital. In return, he would obligate himself to pay the state a

specified fraction of his earnings above some minimum, the fraction and minimum

being determined to make the program self-financing. Such a program would

eliminate existing imperfections in the capital market and so widen the

opportunity of individuals to make productive investments in themselves while

at the same time assuring that the costs are borne by those who benefit most

directly rather than by the population at large (p. 14).

Even if

indirectly, the thoughts of the economist Milton Friedman were, according to Chapman (2005), developed as a possible answer to the problem of

the capital market regarding the financing of education. However, it was not

until the 1980s that arrangements began to be adopted to reach the stage of the

current type of financing with loan characteristics.

For this

purpose, several countries, including European, American, Asian, African and

Australian, have implemented the student loan system. Furthermore, some

organizations, such as the World Bank and banking organizations, have given and

continue to offer their contribution to the implementation of the loan policy.

Information

from ICHEFAP

(2007) used by Vossensteyn (2009) shows that Because of

limited public funds and a growing emphasis on the private returns to higher

education, the 1990s have witnessed a trend towards the introduction of student

loans in countries where they did not exist before. For example, France (1991),

Hong Kong (1998), Hungary (2001), Poland (1998), Slovenia (1999), India (2001),

Egypt (2002), Kenya (1991), South Africa (1994), and the United Kingdom (1991)

have introduced student loans (p. 178).

In the

United States, student loan programs began in 1965 as a way of providing

supplemental help to students who could not attend college or would have to

work excessively in school Williams

(2006).

The

implementation of loan programs in developing countries had the support of

international organizations, such as the World Bank in the late 1990s and early

2000s, including in Indonesia, Namibia, Nepal, Mexico and Rwanda Chapman. (2005).

The

objectives in the implementation of loan systems differ, as clarified by Ziderman

(2002), from case to case, and the difference will

somehow influence the design and functioning of the system as a whole, as well

as its financial sustainability.

The author puts

forth the following five objectives, each of which can incorporate more than

one objective: (i) budgetary objectives (income generation); (ii) facilitate

the expansion of higher education; (iii) social objectives (improving equity

and access for the poor); (iv) satisfy specific labour needs; and (v) alleviate

the financial burden on students.

Thus, according

to the author, the evaluations of loan schemes can provide information on the

degree of success attained in meeting the defined objectives.

Loans can

be public, as is the case, for example, in France, where they are financed by

the Ministry of Education and managed by a university centre with some

exemption from interest and long repayment periods. Loans can also be private,

with the support of banking organizations Chevaillier and Paul (2008).

Taking into

account the objectives and the differences in the types of loans, which can be

public or private, a reflection follows on the possible challenges of loans in the

various contexts.

3.2. Current challenges in student loan systems

Following Chapman (2005), it is widely known that the financing of higher

education entails uncertainty and risk regarding the future economic fortune of

students, and there is a reluctance on the part of banks to provide loans due

to the absence of guarantees. The risk occurs, according to Chapman

and Ryan (2003), because unlike the housing loan, which, in the

event of default, the bank has something to sell, the education loan does not

offer the same guarantees.

This

implies that, without State assistance, banks will not be interested in

underwriting investments in human capital and, consequently, it can be a

regressive system for several reasons: loss of talent; a huge cost to society

as a whole; loss of opportunity for individuals; possible horizontal social

mobility.

This is why

most student bank loan programs around the world are government-assisted, in

which they commit to repaying the loan if the borrower is unable to do so due

to unemployment, illness or death Woodhall

(2004); Chapman

and Ryan (2003).

This

government intervention emerges as a solution to the capital market problem or

market failure presented by several authors Teixeira

(2006); Woodhall

(2004); Chapman

and Ryan (2003); Chapman (2005).

One of the

problems of this agreement, according to Woodhall

(2004) and Chapman

and Ryan (2003), is that it can somehow encourage the borrowers’

dropout and, furthermore, prevent banks from pursuing them because of government

guarantees.

In general,

statistics, according to the same authors, have shown that the average dropout

rate has been between 15% and 30%, and in countries such as the United States,

the rate is as high as 50%.

Williams

(2006), in a study entitled Debt Education: Bad for the Young, Bad for America, shows that in the

loan system, in its first twelve years, from 1965 to 1978, the amounts borrowed

were relatively small, largely because the University education was

comparatively cheap, especially at public universities. In the early 1990s, the

program grew immodestly, corresponding to 59% of the highest educational financial

support the government offered, surpassing all grants and scholarships.

For the

author, the excess or accumulation of indebtedness among students went beyond a

way of financing the university in order to create social well-being, but it

became a mode of pedagogy. It implicitly entailed a shift in the conception of

higher education from a public good to a private good, breaking the

intergenerational pact of the social welfare university.

This

thought is also shared by Zeleza

(2016) when he mentions that debt from loans teaches

students that higher education is a service to the consumer, promoting

careerism and the primacy of the capitalist market. It also teaches that the

role of government is to serve the market, not the public interest, and a

person’s worth is measured according to one’s financial potential rather than

the content of a person’s character. Moreover, the culture of debt has

instilled high levels of stress and a fear-of-failure sensitivity.

In addition

to these matters that are structural in the issue of loans, nowadays, and even

though many countries have joined, as stated by Ziderman

(2002) and Woodhall

(2004), government-supported student loan programs are in

place in about 50 countries.

Cerdeira

(2008) emphasizes that student loans have been designed

in several countries to accommodate, as much as possible, two characteristics:

the socio-economic conditions of the countries and of the students who aspire

to attend higher education, and the universal availability, that is, any

academically prepared student should be able to study and have access to a

loan.

Therefore, Ziderman

(2002) maintains that the analysis of the functioning of

the regimes of each country reveals a considerable variation from one program

to another, defying any attempt to identify common or even better practices.

According to the author, some schemes are available to students from all

university sectors (both private and public), whereas others are restricted to

students enrolled in institutions from the public sector.

In addition

to the market failure, which is one of the major problems at the institutional

level, as already mentioned, for the student support system through bank loans,

Chapman

and Ryan (2003) show that the

other problem arises on the part of students, one the one hand because some are

reluctant to borrow due to fear of not meeting future payment obligations, with

concomitant damage to the reputation of a person. On the other hand, potential

students may not be prepared to take out bank loans, in part because banks are

not sensitive to the borrower’s financial circumstances related to default

risk.

Besides

market-related issues, loans also deal with cultural issues, which, according

to Usher (2018), need to be solved, as it is very common in

Islamic cultures not to like the idea of remunerated debt.

For

example, in a survey commissioned by the author in Indonesia on attitudes

towards debt, many participants responded that they would not take out student

debt but would make other types of debts to purchase o housing, transport and

other goods.

For this

particular case, Vossensteyn (2009) states that this requires a lasting strategy, with

clear information on the lifetime costs and benefits of higher education and

the government’s guarantee that students will not be impaired if their future

situation of employment is not good.

According

to Usher (2018), in student debt aversion, the real problem is not

the debt itself, but the value of money, and this debt aversion is more

associated with poorer students because their appreciation of the costs and

benefits of education makes them less likely to participate.

These and

other issues lead to disagreement and sharp questions about whether student

loan systems are viable or whether they can always work successfully,

particularly in developing countries. When the answer to the question is yes,

another question emerges: how to best design and manage student loan programs

effectively? Barr

(2005).

The

solution to this problem is not necessarily to reduce loans, but to reduce loan

risk. Usher (2018) sustains that income-contingent loan programs,

which allow people to suspend payments when income is low, are an important and

potential tool for the loan issues presented here.

Even so,

the loan system has been questioned by Vossensteyn (2009) in terms of to

what extent it is a social good, insofar as

Loans much more

imply a private cost than grants because student loans must be repaid. Through

loans students rather than general the taxpayers pay part of the costs of

study. But loans also include costs, such as administration, interest

subsidies, and costs of non-repayment (default) (p. 177).

Some studies on the cost and access to higher

education carried out in countries, such as Australia, to assess the impact of

one of the loan program models that is a standard for several countries, HECS

(Higher Education Contribution Scheme), has revealed, according to Chapman and Ryan (2003), [that]

neither the introduction of, or radical changes to, HECS have had major effects

on the average financial attractiveness of a university education, which

remains high. It would be reasonable to conclude from this that, in aggregate,

it is unlikely that HECS has had an important effect on the demand for higher

education. […] HECS has not been a dominant factor influencing individual

decision-making, […] for low socioeconomic status groups (p. 12).

Regarding student reactions, Vossensteyn (2009)

states that, although in many countries, student loans are “conventional loans”

in the sense that they have relatively strict repayment terms, such as a

relatively short repayment period, fixed monthly instalments and a

high-interest rate. For example, in Australia and the UK, payments are

automatically taken from the gross salary by the tax authorities, which has

caused a lot of criticism from the student unions. According to Johnstone (2005),

students would presumably always prefer that their support be non-reimbursable,

that is, that it be in the form of subsidies, in addition to low tuition,

subsidized housing and food or heavily subsidized loans.

To show some sensitivity to the loan program and its

controversies, both social and political in some contexts, Woodhall (2004)

mentions the classic case that took place in Africa, in Ghana, when students’

opposition to the introduction of loans in 1971 contributed to the fall of the

government and, in the following year, the abandonment of the loan system and

its reintroduction in subsequent years in a more interesting way, contrary to

what happened in the first experience.

Due to the challenges of loan systems as a form of

social support for students, reality has revealed that some programs are

considered highly successful, but others face enormous difficulties, and some

have already been discontinued Woodhall (2004)

As a way of improving loan programs, several proposals

have been raised, with emphasis on the case of Wellhausen (2006) who,

in the report of the conference on student loans held in Oxford on January

27-29, 2006, presented summarily the following characteristics of the loans

that he deems well designed and conceived: Loan programs had to be sufficiently

extended to all students; the interest rate must be rational; and the

reimbursement mechanism must be efficient, equitable and capable of being

implemented.

Therefore, Johnstone (2001) advocates four

main ways for the government to participate in student loans: 1. Full coverage

or at least a significant part of the risks. 2. Interest rate subsidy, or the

cost of loans repaid by the student borrower. 3. Absorb some of the costs

administered in the loan program.

4. Employ the student to collect the loan through tax.

Furthermore,

in any assessment of loan programs, Ziderman

(2002) advises that there cannot be a standard approach

to assess the effectiveness of loan schemes. A given student loan scheme needs

to be assessed in the context of the core objective(s) for which it is

intended. By contrast, equity-targeted loan schemes, designed to increase

university access for the poor, should be assessed primarily in terms of their

success in reaching these populations and the extent to which the availability

of loans increases the participation of the poor in higher education.

A study

that draws on international lessons and experiences on loans by Woodhall (2004) concluded that loans tend to work better

when combined with scholarships rather than being the only form of financial

support. The study also reveals that it is necessary to look at the conditions

of the countries in the implementation of the student loan system, particularly

in African countries. The author further suggests that whenever a loan system

is intended to be implemented in these contexts, it should be based on a

feasibility study and gradually implemented.

4. Presentation and discussion of data

4.1. Loans made by higher education students in the province of Gaza, Mozambique

Student

loans, as a state-subsidized higher education funding policy, have been sought

after by several individuals as a source of funding for higher education

studies in many countries.

However, it

should be noted that the model of student loans in Mozambique is not similar to

the specific student loan program packages that have been used in other

countries, inasmuch that Mozambique has not yet implemented the same model,

according to information from the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher

Education, and Vocational Training (2018).

In this

case, the loans that will be mentioned here are trivial loans granted by banks

without any co-payment or guarantee from the State.

The study

sought to understand whether students, in addition to other funding sources,

such as family, salary and scholarships, resorted to loans in the financial

market to pay for their studies.

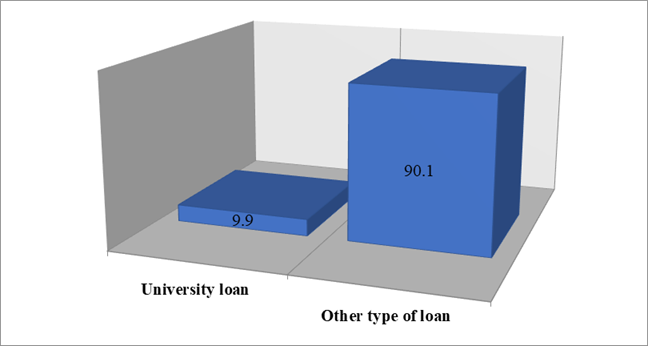

Regarding

the type of loans taken out by students, data revealed that most students state

that they have taken out other sorts of loans that, according to them, are

related to credit for housing and consumer goods. Only a few requested the loan

packages that banks promote to cover expenses related to the studies that we

name University Credit Figure 1.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Type of Loan Taken Out

(%) Source: Produced by the Authors. |

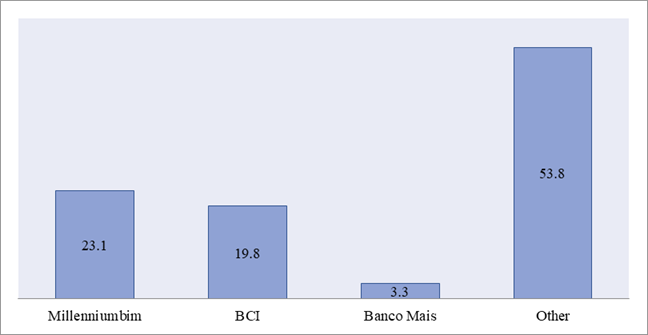

Concerning the entities where the students obtained the loans, the majority of students (53.8%) also chose the option Other. This category encompasses formal means, such as government institutions, some institutions such as Micro finance banks, and also informal means, such as Xitique[1] and personal loans.

In addition to other means, students also use

commercial banks, such as Banco

Millenniumbim, with 23.1%, Banco

Comercial de Investimento-BCI, with 19.8% and, finally, Banco Mais, with 3.3%.

The fact that many students resort to other sources of

loans to pay for their higher education studies, as shown in Figure 2 below,

may reveal that potential loan packages for students subsidized by the State would

be a positive alternative to diversifying social support for studies.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Entities

that Granted Loans to Higher Education Students Source: Produced by the Authors. |

The

teaching sector that showed the highest number of students who have taken out

the loan in various entities presented above is the Public University sector

(20%), followed by the Private University sector (17.8%). Private Polytechnic

students did not take out any loans, whereas 12.7% of Public Polytechnic

students did, according to Table 1. However, the differences between students who

took out loans and those who did not are statistically significant (χ2(3)=3,955;

p>0,266).

|

Table 1 Relation of the Loan Application According to the Sector and Type of Education |

||||||

|

Yes |

No |

Total |

||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

Public University |

43 |

20.1 |

171 |

79.9 |

214 |

100.0 |

|

Public Polytechnic |

15 |

12.7 |

103 |

87.3 |

118 |

100.0 |

|

Private University |

27 |

17.8 |

125 |

82.2 |

152 |

100.0 |

|

Private Polytechnic |

0 |

0.0 |

5 |

100.0 |

5 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

85 |

17.4 |

404 |

82.6 |

489 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Produced by the Authors. |

||||||

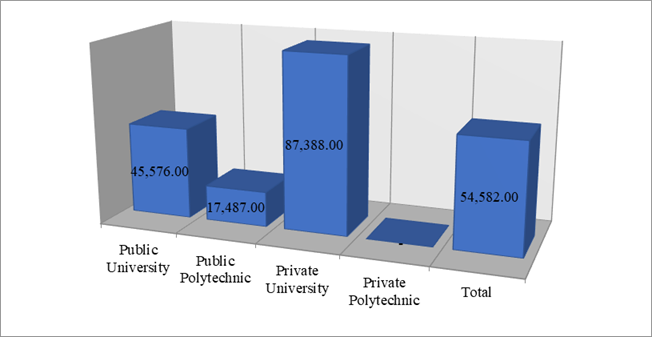

Regarding

the sector and type of education, despite having been verified in Table 1 that the largest number of students who applied

for a loan were attending the public sector, students enrolled in Private

University Education contracted, on average, loans with higher values

(87,388.00 MT) vis-a-vis students from Public University (45,576.00 MT) and

Public Polytechnic (17,487.00 MT). For Private Polytechnic education, as shown

in Figure 3, column 3, there is no indication of loans made by students.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Amount of

Loans Taken Out by Higher Education Students by Sector and Type of Education

(MT) Source: Produced

by the authors. |

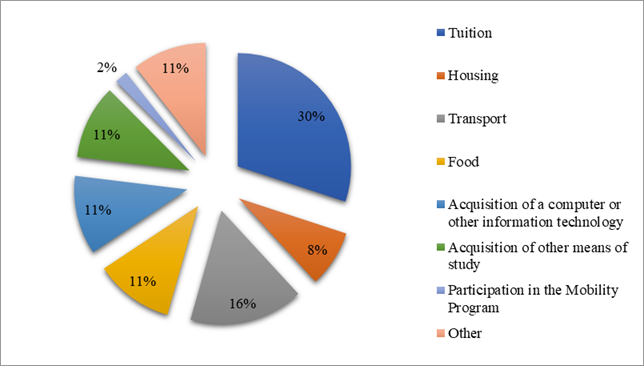

As already

mentioned concerning the type of loans that students use, while it is not a

loan in the way that has been developed in many countries around the world, 30%

of the students responded that they had taken out loans to cover

tuition-related expenses, then 16% to cover transport expenses, 11% responded

to cover food expenses, acquisition of teaching materials and other means of

studies, and only 2% responded they had taken out the loan to participate in a

mobility program Figure 4.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 The Reasons that Led

Students to Take Out the Loan Source: Produced by the

Authors. |

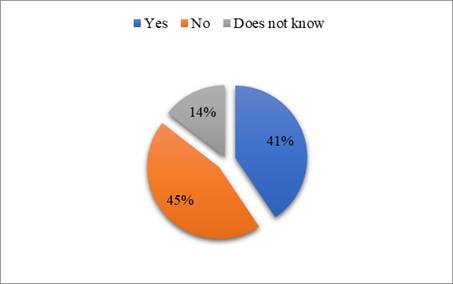

When asked whether

they would have taken out a larger loan if they could, most students (45%)

replied that they would not have. However, an also expressive percentage of

students (41%) stated that they would have taken out a higher amount. Only 14%

said that they did not know whether they would choose to ask for a higher

amount or not, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 If I Could, I Would have Taken Out a Bigger Loan Source: Produced by the Authors. |

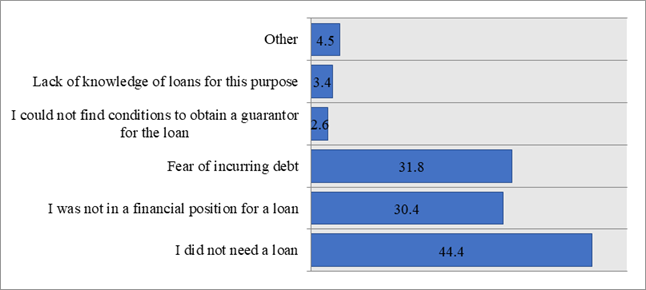

Regarding

the students who answered not having taken out a loan, there are several

reasons for that; among them, they did not feel the need to do so (44.4%), they

were not in financial conditions to do so (30.4%), and they feared getting into

debt (31.8%) Figure 6.

The issues

related to the fear of indebtedness from loans have been put forward by several

authors, namely Usher (2018), Vossensteyn (2009), and Barr

(2005), as previously stated. However, as a way of

minimizing these constraints, some authors, such as Vossensteyn (2009), advise making it very clear to students/families

from the beginning of the process, depending on the type of loan, especially

when it comes to state-subsidized loans, that they will not have to worry about

paying until they have a source of income.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Reasons for not Having Taken Out a Loan Source: Produced by the

Authors. |

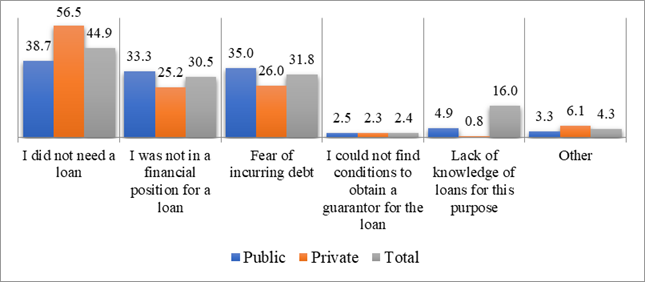

Most students

who stated they did not need a loan to pay for their studies are enrolled in

the private higher education sector (56.5%) versus 38.7% in the public sector.

The majority of the students who were not in a financial position to ask for a

loan are enrolled in the public sector (33.3%) against 25.2% in the private

sector. Most of the students who were fearful of incurring debts are also enrolled

in the public sector (35%) compared to the private sector (26%) Figure 7.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Reasons for not Having Taken out a Loan Source: Produced by the

Authors. |

Thus, the

loans taken out by students in Mozambique are loans without State co-payment, unlike

other countries that have loan policies specifically for university students. This

attitude of students to resort to commercial loan modalities to pay for their

studies should lead to a reflection on a possible introduction of the specific

loan modality to support students who want to pursue their studies after concluding

secondary school. This could broaden the range of funding sources for higher

education in Mozambique besides scholarships.

Information

from the report on the implementation of reforms in the financing of higher

education in Mozambique reveals that the establishment of a student loan scheme

in Mozambique is still in the research and pre-project stage; student loans

will come into operation once the project is tested Fonteyne

and Jongbloed (2018).

However,

its implementation should take into account the experiences reported in studies

carried out in different contexts so that its introduction is appropriate to

the economic and social context of the country and the families.

Loans in

the context of African countries are already a reality, according to data from ICHEFAP (2007), in a comparative study of cost-sharing programs, which indicates that

student loans started in some African countries in the 1970s and early 2000s,

according to Table 2.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Cost-Sharing Program in Some Countries on the African Continent |

||

|

Countries |

Cost-sharing

policies |

Student

loan program |

|

Ethiopia |

Dual

tuition fee teaching: enrolment tuition, housing and food covered by regular

students. After-work

education: students pay all expenses. |

In 2003,

the Australian model loan program began. |

|

Kenia |

Tuition

fees, housing and food fees were introduced in 1992, but the tuition fee was

reversed due to disputes. Dual fee courses started in 1997 at the University

of Nairobi. |

A

comprehensive loan program was introduced in the 1970s but failed without

recovering values. The program restarted in 1995 with a Higher Education Loan

Board with greater self-sufficiency vis-a-vis the first program. |

|

Tanzania |

Cost-sharing

officially started in 1992 but at a slow pace. Maintenance allowances,

housing allowances, and food were reduced in the mid-90s. It also introduces

dual-rate tuition teaching. |

Introduction

of a loan scheme implemented in 1993-94 as part of phase II of cost-sharing

to cover a portion of housing and food costs. As of 2003, no interest rate,

no collection strategy and no recovery of values were stipulated. |

|

Uganda |

The

University of Makerere is famous for being aggressive and successful in its

teaching dual-fee system, with over 75% of students paying a fee, which has

brought financial benefits to the institution. |

Under

discussion: no operational student loan program since 2003. |

|

Botswana |

Limited

cost-sharing measures were introduced in 2002-3, along with efforts to

improve loan collection. |

Under

discussion: no operational student loan program since 2003. |

|

South

Africa |

Tuition

fees and cost-sharing have fees ranging from US$1000-3500. |

An

income-tested loan program collected by employers. It reaches around 20% of

the student population, 2% real interest, and repayment is 3-8% of income

above the threshold. |

|

Ghana |

Cost-sharing

is limited to small fees for housing and food usage, with no tuition fees. |

After the

collapse of the 1970s plans, a new scheme was put in place in 1988. High

subsidies and difficulties in collecting values persist. |

|

Nigeria |

The

government expects 10% of costs to come from other income sources, but

cost-sharing is controversial, with nominal fees for housing, food and

monthly tuition at state – but not federal – universities. |

As in

Ghana, the Student Loan Board failed to collect and was suspended in 1992. A

new bank is building measures to increase collections and interest rates. |

|

Burkina Faso |

Despite

the French-speaking tradition of no fees, the country began cutting back on

donations and starting with a modest tuition rate in the 1990s: an increase

from about US 12 to 24 in 2003, which brought strong student opposition. |

Small

loan program. Resource-tested loans managed by Prets FONER[2], started in 1994 for 2nd

and 3rd cycle students. Subsidized and contingent income of 1/6 of

salary. With little recovery so far. |

|

Source: Adapted from ICHEFAP

(2007) |

||

As can be

seen, studies have revealed that the student loan system around the world

raises many controversies and few African countries have a solid system in

terms of organization and social acceptance.

Controversies

have also created a certain division among researchers, with groups in favour

and groups against the student loan system.

As can be

read in Cerdeira

(2008) doctoral thesis referring to Woodhall

(2004), some groups are in favour of the student loan

system and justify that they can bring some efficiency and equity. They can be

part of the burden on the government budget and taxpayers, and provide

additional resources to finance the expansion of higher education so as to

broaden access and make students aware of the costs of higher education, thus

forcing them to assess costs and benefits in light of the obligation to repay

their loans.

According

to Woodhall

(2004), those who take on an opposing stance argue that

higher education is a profitable social investment and, therefore, should be

financed by public and not private funds, due to the complexity and high costs

of administration in collecting loan repayments, the risk of non-reimbursement

for a variety of reasons, the danger of distorting students’ choices in terms

of professional careers to pursue, encouraging them to opt for high salaries

rather than study programmes or jobs that may be socially valuable but offer

prospects for low profits.

When

looking at most of the African context, the challenges become even greater.

First, because of the challenge of unemployment, which makes students take a

long time to start returning the amount spent studying; second, as a

consequence of the first, the existence of many income flows, usually informal

and often undeclared and difficult to trace, which are characteristic in

developing countries Johnstone (2003).

The other

challenge to take into account, which may go unnoticed at some point, is

related to the cultural issues that may be raised by reimbursable social

support to finance higher education, as already mentioned by Usher (2018). Studies in some contexts have revealed that

families adhere more to loans to purchase material goods and less to studies,

which are long-term investments.

This

attitude is motivated by cultural symbolic values regarding the importance

people attach to money to buy something visible or invest in something with

immediate returns. Since education is a long-term investment, people tend to

resist this type of investment, leaving it to the State to handle.

5. Conclusion

With the

need to expand the social support system, several countries have resorted to

student loan policies as an alternative. This study revealed that, despite the

already known social and economic conditions that characterize a majority of

the Mozambican population and the fears about taking out the loan shown by some

students, a significant number of students mentioned resorting to both formal

and informal financial institutions to apply for loans as a way to fund their

higher education studies.

This may

reveal some interest on the part of students and families, especially if the

loans are co-paid by the State, given that the majority of students revealed

that they use loans to defray the expenses related to studies, i.e., in the

payment of tuition fees, subsistence expenses and transport.

However,

its implementation should take into account the constraints that characterize

developing countries and that relate to the flow of income, which is generally

informal, undeclared and difficult to trace. First, it will require designing a

loan model that is affordable, considering the social and economic conditions

of most Mozambican families. Second, conditions must be created for legal

authority, equipped with the technology to keep accurate records and with

consultants and advisors who follow up with borrowers, are in charge of lending

and collecting loans and have the ability to mobilize both government

institutions that charge taxes and employers on the reimbursement of the loans.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Barr, N. (2005). Financing Higher Education :

Lessons from the UK Debate. LSE Research Online, (June), 371-381.

Cerdeira, M. L. (2008). O Financiamento do Ensino Superior Português. A Partilha de Custos [The financing of Portuguese Higher Education. Cost-sharing]. University of Lisbon, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences. Faculdade de Lisboa.

Chevaillier, T., & Paul, J.-J. (2008). Accessibility and Equity in a State-Funded System of Higher Education : The French Case. In P. N. Teixeira, D. B. Johnston, M. J. Rosa, & H. Vessensteyn (2008). Cost-sharing and accessibility in higher education: A fairer deal? Dordrecht : Springer, 295-317.

Chapman, B., & Ryan, C. (2003). The Access Implications of Income Contingent Charges for Higher Education : Lessons from Australia.

Chapman, B. (2005). Income Contingent Loans for Higher

Education : International Reform. CEPR Discussion Papers 491, Centre for

Economic Policy Research, Research School of Economics, Australian National

University.

Fonteyne, B., & Jongbloed, B. W. A. (2018). Implementing the Strategy for Financial Reform of Higher Education in Mozambique (EFES). Enschede : CHEPS – Center for Higher Education Policy Studies.

Friedman, M. (1955). The Role of Government

in Education. New Jersey : Trustees of Rutgers College.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Liberty. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Hauptman, A. (2007). Higher Education Finance: Trends and Issues. In J. J. F. Forest, & P. G. Altbach (Eds.), International Handbook of Higher Education. Dordrecht: Springer, 83-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4012-2_6

ICHEFAP (2007). International Comparative Higher Education Finance and Accessibility Project.

Johnstone, D. B. (2001). Student Loans in

International Perspective : Promises and Failures, Myths and Partial Truths.

Johnstone, D. B. (2003). Higher Education Finance and Accessibility: Tuition Fees and Student Loans in Sub Saharan Africa. Journal of Higher Education in Africa, 2, 201-226.

Johnstone, D. B. (2005). Higher Educational Accessibility and Financial Viability: The Role of Student Loans. Barcelona.

Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education, and Vocational Training (2018). Scholarships in Mozambique. Maputo : National Directorate of Higher Education.

National Directorate of Higher Education (2021). Statistics of Students (2010-2018). Maputo : Ministery of Sciences, Technology and Higher Education.

Teixeira, P. N. (2006). Markets in Higher Education: Can We Still Learn from Economics, Founding Fathers? UC Berkeley : Center for Studies in Higher Education, 22.

Usher, A. (2017). Notes on Medieval

Higher Education Fiqnance.

Usher, A. (2018). Financial Barriers. May 10.

Vossensteyn, H. (2009). Challenges in Student Financing: State Financial support to Students: A Worldwide Perspective. Higher Education in Europe, 34(2), 171-187.

Wellhausen, R. (2006). Student loans in Russia. Oxford : Oxford Russia Fund.

Williams, J. J. (2006). Debt Education :

Bad for the Young, Bad for America.

Woodhall,

M. (2004). Student Loans : Potential, Problems, and Lessons from International

Experience. Journal of Higher Education in Africa / Revue de L'enseignement

Supérieur en Afrique, 2(2), 37-51.

Zeleza, P. T. (2016). The Transformation of Global Higher Education, 1945-2015. New York : Palgrave Macmillan.

Ziderman, A. (2002). Alternative Objectives of National Student Loan Schemes: Implications for Design, Evaluation and Policy. The Welsh Journal of Education 11(1), 37-47.

[1] It is a form of informal

association, in which a group of people who are usually close to each other

contribute with monetary values regularly so that each one receives all the

contributed values on a rotating basis.

[2] NatiAonal Education and Research Fund.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2023. All Rights Reserved.