Local Wisdom as an Environmental Conservation Endeavor in Selalejo Village and East Selalejo Village, Mauponggo District, Nagekeo Regency

Ebu Kosmas 1![]() , Rafael Tupen 2

, Rafael Tupen 2![]()

1, 2 Faculty

of Law, Nusa Cendana University, Kupang, Indonesia

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The indigenous

community of Selalejo possesses a local wisdom

known as "Tanda," which proves highly effective in the preservation

of the environment. "Tanda" signifies the act of providing symbols

or codes in the form of young palm leaf shoots, primarily attached to trees

at specific locations along with the jawbone of a pig, after its meat has

been consumed during a customary ritual signifying the commencement of

indigenous law related to "Tanda”. Through the presence of

"Tanda," the environment, including land, forests, plantation

crops, and crops, is safeguarded from logging, harm, and the threat of

looting or theft through the symbolic messages conveyed by the arrangement of

leaves and pig jawbones hung on these trees. The philosophical foundation of

"Tanda" is rooted in the idea that humans and the natural

environment are inseparable entities. This connection is grounded in the

belief that the earth and water constitute the body and blood of humanity,

which manifest in the form of a mother (Mother Earth) upon which all plants

and vegetation thrive. Moreover, various religions hold the view that the

entire universe (earth, water, and the life upon it) is the creation of God.

Human beings are entrusted with the responsibility of stewardship, which

entails safeguarding, preserving, and managing these resources in a

responsible and non-arbitrary manner. The existence of the "Tanda"

customary law within the indigenous community of Selalejo

serves as a social control mechanism and a tool for social engineering aimed

at transforming undesirable behaviors related to irresponsible and arbitrary

resource utilization. In cases of violations of the "Tanda"

customary law, enforcement is carried out by traditional institutions. |

|||

|

Received 09 August 2023 Accepted 10 September 2023 Published 30 September 2023 Corresponding Author Rafael Tupen, rafael.tupenfh@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/granthaalayah.v11.i9.2023.5327 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Local Wisdom, Tanda, Environmental

Conservation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The indigenous communities of Sela and Lejo are situated within the administrative jurisdiction of Selalejo Village and East Selalejo Village. These two indigenous communities, hereinafter referred to as Selalejo, do not reside within a specific village, as individuals from the Sela indigenous community may choose to reside in either Selalejo Village or East Selalejo Village, and likewise, members of the Lejo indigenous community may opt to reside in Selalejo Village or East Selalejo Village. Meanwhile, the Indigenous Leaders (Mosa Mere Laki Lewa) of each indigenous community are located in the traditional villages of Sela and Lejo, both of which are situated within East Selalejo Village. However, each of these communities stands independently alongside their respective cultural and institutional components. They possess their own cultural and institutional elements and maintain collective environmental stewardship based on land and water rights for all their members. Nevertheless, both indigenous communities ascribe social functions to forests and water bodies, as they share a common ancestry in the formation of the Sela and Lejo indigenous community groups, and up to the present time, they remain genealogically and territorially interconnected.

From an administrative governance perspective, East Selalejo Village is an administrative subdivision derived from the parent village, Selalejo. Currently, there are plans to further subdivide into two more preparatory villages. Despite the administrative separation at the village governance level, in the customary expression of the Sela-Lejo indigenous community, the saying goes: "Ine imu a metu mite, ame imu a lalu toyo" (originating from the same black rooster and the same father, namely the same red male). This signifies that even though administrative divisions have resulted in multiple villages, and there has been a grouping of the indigenous communities (Selalejo Raya) based on customary practices, they remain one extended family known as Selalejo Raya (Interview with Blasius Witu, Indigenous leader of Sela-Lejo. 2022).

According to Hazairin indigenous communities can be understood as social units that possess the necessary components to stand independently, including a unified legal framework, governing authority, and a shared environmental context based on collective land and water rights for all members. The form of their kinship system (patrilineal, matrilineal, or bilateral) influences their governance system, particularly rooted in agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, and the collection of forest and water resources. This is supplemented by limited hunting of wild animals, mining activities, and craftsmanship Soekanto (1983).

From a legal perspective, indigenous communities are defined as social groups that, through generations, have settled in specific geographic regions due to their ancestral heritage, strong ties to the environment, and a value system that shapes their economic, political, social, and legal structures (Article 1of law Number 32 of 2009 on Environmental Preservation and Management).

The indigenous community of Selalejo exhibits a legal unity, a unified governing authority, and a shared environmental context based on collective land and water rights for all its members. In managing the environment, particularly in terms of conservation, this indigenous community possesses local wisdom.

In Article 1, point 30 of Law Number 32 of 2009 Environmental Preservation and Management, it is emphasized that "Local wisdom is the noble values prevailing in the community's way of life, including, among other things, the sustainable protection and management of the environment." Meanwhile, Putu Oka Ngakan, as cited in Abdul Asis Nasihuddin's work Nasihudin (2017), defines local wisdom as the set of values or behaviors of local communities in their interactions with the environment in a prudent manner. Etymologically, wisdom refers to an individual's ability to employ their intellect in responding to an event, object, or situation, while local signifies the contextual space in which events or situations occur. Therefore, local wisdom fundamentally represents the norms established in a community, believed to be true, and serving as a reference for daily actions and behaviors.

The Selalejo indigenous community possesses a local wisdom known as "Tanda" in their efforts toward environmental preservation. In the context of the Selalejo indigenous community, "Tanda" signifies the act of providing symbols or codes in the form of young palm leaf shoots, primarily bound to trees at specific locations along with the jawbone of a pig. This ritual follows the consumption of the pig's meat during a ceremony or ritual, symbolizing the formal initiation or commencement of the customary law associated with "Tanda”. "Tanda" is intrinsically linked to environmental conservation, encompassing land, forests, the vegetation that thrives within them, plantation crops, and crops. It serves the purpose of preventing indiscriminate logging, and unwarranted destruction, and safeguarding against looting or theft through the transmission of symbolic messages via the arrangement of leaves and the presence of pig jawbones hung on these trees.

In the event of a violation of the local wisdom known as "Tanda”, the perpetrator faces a severe customary sanction referred to as "Poke Sega" (literally meaning being thrown and pierced/thrust with a spear). This entails a penalty in the form of a large pig being slaughtered for communal consumption. The objective behind this sanction is to preserve and responsibly manage the environment, encompassing the earth, water, forests, and the plant life upon them, prudently and wisely.

This customary sanction aligns with what B. Ter Haar has articulated regarding violations (delicts). It pertains to any one-sided disturbance of equilibrium and any encroachment upon the material and immaterial aspects of an individual's or a collective group's livelihood. Such actions trigger a reaction, the nature and magnitude of which are determined by customary law and are termed a customary response (adatreactie). This response is instrumental in restoring and maintaining balance Ter Haar (1987).

The underlying rationale behind the practice of "Tanda" from the perspective of local wisdom, as expressed by the indigenous community of Selalejo, is encapsulated in the adage: "mo'o waja nga ko'o olo toni taga... ka waja, puka muak, toa tomu, tanda tu’u ri waja." In the eyes of the Selalejo Indigenous community, this adage signifies that all efforts, crops, and plants must reach their appropriate harvesting time before they can be collected (Interview with Marthinus Btoh Bae, Indigenous leader of Lejo Indigenous community, 2022). While this may seem logical, the observed phenomenon is that people engage in deforestation without considering the environment, replacing forests with plantation crops like cloves that are unable to retain groundwater and even causing the depletion of water sources. This has also made the region susceptible to landslides, especially in the topographically inclined and hilly areas of Selalejo and East Selalejo. Another concerning issue is the theft of crops or agricultural produce owned by others before the harvest season.

Considering these observed phenomena and issues, primarily stemming from the irresponsible actions of some individuals, "Tanda" emerges as a solution for the Selalejo indigenous community. It should be respected and upheld as both a social control mechanism and a means to redirect deviant behavior toward the right path. In light of these considerations, the research poses the following questions: (1) What is the philosophical foundation of "Tanda" from the perspective of local wisdom as an endeavor for environmental preservation? (2) To what extent can the existence of "Tanda" in the context of local wisdom influence environmental conservation?

2. RESEARCH METHOD

This research can be categorized as an empirical legal study. According to Soerjono Soekanto, socio-legal or empirical legal research encompasses the examination of legal identification (unwritten) and the assessment of legal effectiveness Soekanto (1986). Meanwhile, Muslan Abdurrahman states that if the research problem is answered through field research, then the researcher's approach employs a socio-legal perspective Abdurrahman (2009). This study pertains to "Tanda" as a customary legal regulation within the Selalejo indigenous community, the authority of customary institutions (indigenous leaders or elders, and "ine tanda"), and the indigenous community in enforcing customary legal rules as a reality within the community. Therefore, the approach is a socio-legal one, focusing on the examination of customary law within the indigenous community.

The assessment primarily centers on two aspects: First, "Tanda" as a local customary ritual and the philosophical basis for its enforcement and preservation as law by the indigenous community and customary authorities in the pursuit of environmental conservation. The indicators under examination include a) "Tanda" from the perspective of human-environment relationships; and b) "Tanda" from the perspective of human-environment relationships with the divine. Second, the influence of the existence of "Tanda" from the perspective of local wisdom on environmental conservation, with indicators including a) The structure/institutions of customary law; and b) The existence and functions of customary legal institutions.

The type of data used in this research consists of primary data, obtained directly from the research location through direct interviews with respondents, including traditional leaders, religious figures, youth leaders, and village government officials. Secondary data is also used, obtained through literature studies, relevant publications, and expressions within customary law that serve as guidelines within the local indigenous community.

3. RESULT AND DISSCUSION

The "Tanda" as a local wisdom is conducted through a highly authoritative ritual and carried out based on the consensus of the local indigenous community (in a democratic manner). It is recognized as a law that must be enforced and adhered to. By performing the "Tanda" ritual, sanctioned by indigenous leaders along with the heads of clans and witnessed by the entire Selalejo indigenous community, a new legal order is established, namely, the Customary Law of "Tanda”. This is where human beings gain significance in their relationships with one another, guided by the Customary Law of "Tanda." The initiation of this new way of life primarily involves the preservation of the environment, the maintenance of harmony between humans and the environment, and the relationship between humans and the natural surroundings with the Creator of the universe, God.

The Selalejo indigenous community firmly believes that above, in the highest realm, there is the Supreme Ruler who governs all powers on earth and beneath the earth. This is the Creator of the universe (Ndewa Reta), and beneath the earth, there is a ruler who maintains the balance between humans and the environment (Ga’e Rale). They believe in the existence of Ndewa Reta and Ga’e Rale, the creators of the universe and the guardians of the balance between humans and the environment. To maintain the harmony and balance of human life and the environment, the interaction within the community requires a set of rules, the Customary Law of "Tanda”, to serve as a guiding star in the realm of law. In terms of legal function, as stated by Achmad Ali, the law functions as a tool of social control and, at specific times and places, simultaneously serves as a tool for change or social engineering Ali (1996).

When a community can formulate or determine its laws and bind itself to existing laws, such a community is referred to as a legal community Kosmas (2018). Society and law are two elements that are difficult to separate and can only be distinguished, as Cicero put it, by the term "Ubi Societas Ibi Ius" (where there is a society, there is law) Ranggawidjaja (1998). Similarly, in the Selalejo indigenous community, customary law is always placed at the forefront of communal life.

The researcher explores the responses of the Selalejo indigenous community regarding the existence of "Tanda" in shaping their collective life, and the respondents' answers are presented in the following table.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Community Responses Regarding the Existence of "Tanda" as an Effort Towards Environmental Preservation |

|||

|

Number |

Answers

Category |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

1 |

Strongly

agree |

32 |

91,43 |

|

2 |

Less

agree |

3 |

8,57 |

|

3 |

disagree |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

35 |

100,00 |

|

|

Source Primary Data, 2022 |

|||

The table above indicates that the community's response is highly positive regarding the notion that "Tanda" should be an integral part of the efforts made by the indigenous community to preserve the environment. It serves not only as a social control mechanism but also as a means for mutual vigilance to ensure that the agricultural and plantation yields belonging to others or fellow community members are protected and monitored, thus resulting in an abundant harvest ("uma dhatu waja nga jeka dhu keti sa’e pu’I koti"). Three respondents (8.57%) who expressed their disagreement were, in fact, young individuals who may not fully understand the meaning of "Tanda".

Based on this initial aspect of the research, several indicators or variables have been identified for further investigation and discussion, as follows:

3.1. "Tanda" from the Perspective of Human-Environment Relationships

It has been previously explained that the goal of development, as mandated by the 1945 Constitution, cannot be separated from humans and the environment. Humans in development must preserve and harmonize the environment as a relationship forming an ecological system called an ecosystem. I Nyoman Baratha states that an ecosystem views the elements within the environment not as separate entities but as integrated components forming a system. If one subsystem is disturbed, the entire environmental system as an ecosystem unity will be disrupted. Therefore, humans, as part of nature, must care for and not exploit nature recklessly Baratha (1991).

The Selalejo indigenous community highly respects appreciates, and practices the messages conveyed in the form of customary verses, such as "ine ebu ta negha welu ko'o pata seru, mo'o kita dhatu tepu siba mona welu jeka ana ebu." The meaning of this message is that what is voiced by the ancestors and predecessors (ta'a mata mulu re'e lo'e) must be upheld from generation to generation. This is the message of the ancestors that ignites their spirit: "My ancestors have taken an oath, and my mother's message is, 'My flesh and blood seep into this land, my womb's blood is buried in this land.'" The profound meaning within this message is that "the earth, water, and the vast forest and plants are the flesh and blood of humans and, therefore, should not be harmed but must be preserved, protected, and passed down from generation to generation. Maintain their balance and harmony in their relationship with humans and God.

The natural world, comprising the earth and water, is likened to a mother who gives birth to new life. The new life for humans will grow alongside nature for as long as fate allows (jeka Ga,e Ndewa enga = God, the Highest, calls back). Thus, in the local expression for someone who has passed away, it is commonly said, "negha tama tuka ine" (has returned to the mother's womb). Returning to the mother's womb means returning to the earth/land. This aligns with the teachings of holy scriptures acknowledged by religious leaders, emphasizing that the land/earth is the life and flesh of humans. Therefore, how humans care for, maintain, and preserve their bodies should not lead to destruction. Furthermore, it is elaborated that humans are born from dust/earth by the mother, namely the earth and water, and will ultimately return to dust/earth (Interview with Cerro, Religious Leader, 2022).

The place where we stand, on the land and water, as previously expressed, is where "my ancestors took an oath, and my mother's message is, 'My flesh and blood seep into this land, my womb's blood is buried in this land.'" The message conveyed by the customary leaders, who are also the Head of the East Selalejo Village, Mr. Khris Goa, and several Heads of Departments (KAUR) at the Selalejo Timur Village Office, is that nature and all its components (earth, water, and plants) have a harmonious relationship that must maintain balance. Human needs in development implementation are inevitably tied to the progress of human civilization, and they must use nature with full awareness and responsibility, ensuring that nature does not become wrathful toward humans (Interview with Cerro, Religious Leader, 2022).

The advancement of technology and its development requires humans to keep pace with progress, and humans can utilize nature (forests, land, and water) for development. However, their use should not be arbitrary but should consider the balance of the ecosystem so that nature does not become enraged. Therefore, the Selalejo people say, "Pogo toni, mo'o ti'i welu jeka ngai ana ebu" (cutting down trees in the forest or plants in the fields must be replanted so that future generations can benefit from them again).

What are the consequences if nature becomes angry? Prolonged heat will damage all crops, and the sources of water will disappear; heavy rainfall will result in floods and other disasters like landslides that will damage all plantations and agriculture, as well as bury houses of the residents under the sliding earth; and strong winds will cause destruction to houses and crops. Additionally, improper human relationships or disharmony among people, such as acts like adultery or incest, as expressed by a Selalejo figure, Blasius Witu, who stated, "Tana tu’u, Koya yoa, jeka olo fucu bugu, toni taga negha mona jadi apa”, will lead to hunger, as crops fail to yield produce, and consequently, thefts that disturb the community (Interview with Cerro, Religious Leader, 2022).

When nature becomes angry due to the greedy and arbitrary actions of humans, it can only be appeased through a sacrificial offering (Big Pig) that is imposed upon the wrongdoer who took the produce from someone else's garden or field. Thus, the thief must be subjected to customary penalties before the council of elders (Mosa Laki/Mosa Nua Laki Ola), attended by the entire community, to ensure that the punishment has a deterrent effect on the wrongdoers. Therefore, "Tanda”, as an unwritten law, serves as a tool for social control and social engineering capable of rectifying deviant behavior and guiding it back onto the right path. Those who violate "Tanda" are subject to penalties involving the sacrifice of a large pig, carried out through a ritual known as "Poke Sega”, which is part of customary adjudication decided by the "Mosa Mere Laki Lewa”, along with "Mosa Laki" and "Mosa Nua Laki Ola”, as will be described in more detail in the section on the Structure of Customary Institutions and Their Functions, respectively. In the execution of customary decisions, there is an institution that functions like a prosecutor or police in positive law, namely "Ine Tanda," appointed since the official opening of the "Tanda" ritual.

The term "Ine Tanda" carries a literal meaning where "Ine" signifies Mother, while "Tanda" implies being marked or signified. Therefore, the one leading and executing "Tanda" is referred to as "Ine Tanda”. Although the term "Ine" in the local language is a respectful address for a woman, it's important to note that the individual holding the position of "Ine Tanda" is not necessarily a woman. "Ine Tanda" employs the term "Ine" with a philosophical foundation, as previously mentioned, signifying the mother of the universe (Mother Earth or Mother Nature). Both external observers and the local community of Selalejo often inquire about the name "Ine Tanda" and question why it isn't "Bapak" or "Tua Tanda" (Father or Elder Tanda).

"Ine Tanda”, the term "Ine" being a term of endearment, a plea for compassion from a woman, carries a moral message that all actions and behaviors should not cause pain and sorrow to one's mother. As previously illustrated, the notion that "the earth, water, and all plants are born from a mother" is embedded in the expressions of the people of Selalejo and the surrounding areas. When someone who has passed away is buried in the ground, it is often expressed as "Negha tama tuka ine" (returning to the mother's womb). This signifies that only through a mother's guidance and education can we learn to appreciate and respect the environment (Interview with Kunradus Senda, Leader of Selalejo Village, 2022).

3.2. "Tanda" from the Perspective of Human-Environment Relationships with God

Human beings and their natural environment are two inseparable elements that must be maintained in harmony to ensure the sustainability of the predetermined seasons ordained by the Almighty, whether it be the rainy season or the dry season. In the context of the relationship between humans, the natural environment, and God, the people of Selalejo believe in the existence of supernatural powers known as "Ndewa Reta" and "Ga’e Rale". This means that God, who is "Ndewa Reta”, reigns supreme in the highest realms as the ruler and creator of heaven and earth and all that inhabits them. Meanwhile, "Ga’e Rale" represents other forces that exist on the earth and beneath it, preserving the harmony and balance in the relationship between humans and nature. By maintaining the balance and harmony between humans and humans, humans, and the environment, it means that we, as humans, have preserved and safeguarded the continuity of life together with the surrounding natural environment.

The Christian perspective on the universe can be gleaned from several excerpts taken from the Book of Genesis: "Let the earth bring forth grass, the herb yielding seed, and the fruit tree yielding fruit after his kind, whose seed is in itself, upon the earth" (Genesis 1:11). Who rules over His creation? "And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and the cattle, and all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth" (Genesis 1:26-27). These quotes provide a philosophical foundation that conveys a message to each of us: first, that the universe, including the earth, water, and forests, is the creation of the Almighty God. Second, that we are to have dominion over His created world. This message can be viewed from an ethical/moral perspective, emphasizing that each of us carries the responsibility of managing, preserving, and utilizing it to the best of our abilities in achieving sustainable development. It is from this perspective that a thoughtful reflection on the meaning of humanity as ethical and cultured beings emerges, constantly pondering the existence of this world as a source of lessons and guidance for humankind, acknowledging that humans were created from the earth or dust of the ground, as written in the Book of Genesis.

The deepest meaning that serves as the foundation of human thinking in the Christian perspective is articulated as follows: "Then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature" (Genesis 2:7). "By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return" (Genesis 3:19).

The Buddhist perspective aligns its core teachings with Hinduism when it comes to environmental stewardship. Particularly, the preservation of nature, especially forests, is highly regarded. This reverence for nature stems from the belief that various forms of life exist within forests, and to maintain the harmony of the universe, compassion from the Supreme Deity is essential Supriadi (2014). However, the Islamic viewpoint offers a different perspective on nature and the environment. In Islam, it is emphasized that humans have a reciprocal relationship with the environment, and philosophically, the environment would continue to exist even without humans. Islam regards the entire cosmos as the rightful possession of the Almighty Supriadi (2014). Fachruddin M. Mangunjaya et al., as cited in Supriadi (2018), mention that in several Quranic verses, God declares that the entire universe belongs to Him (Q.S. Al Baqarah, 2: 284). This is a socio-economic principle in Islam. Humans are permitted to reside temporarily within it to fulfill the purposes planned and decreed by God (Q.S. Al Ahqaf, 46:3). Consequently, the environment is not genuinely owned by humans. Human ownership is merely a trust, a deposit, or a loan that must eventually be returned to its original condition. The statements from both Surahs, Q.S Al Baqarah and Q.S. Al Ahqaf, essentially aim to assert that humans are entrusted with the authority or mandate to safeguard, preserve, and utilize the environment to the best of their abilities and with responsibility. Arbitrarily damaging it for any reason is discouraged.

God has entrusted mankind, as sentient beings, with the responsibility to care for, preserve, and utilize the environment in a virtuous and responsible manner. Sin is the consequence when humans transgress and violate God's commandments. Sin originates from the human conscience. It is solely the authority of an individual's inner conscience to discern whether their actions contravene and defy God's directives or not. There is no coercive instrument of authority; it is exclusively based on the authority of the inner conscience (Interview with Hendrik Nuwa and P. Oswald Bule, religious leader, 2022). It is only through intellect and conscience that one can cultivate intellectual acumen, deriving from the wisdom of the conscience and intellectual aptitude. Consequently, virtuous behavior is attained solely through intellectual acumen, guided by the wisdom of the conscience.

The relationship between humans, the environment (comprising the earth, water, and vegetation), and God the Creator is such that humans, as stewards of the environment created by God, are obligated to preserve, and protect it. Ultimately, humans are held accountable to God for their actions concerning the environment at the end of time.

3.3. The Influence of the Existence of "Tanda" from the Perspective of Local Wisdom on Environmental Conservation

The existence of "Tanda" as depicted within the institutional structure of customary law can be described in terms of its influence on the preservation of the human environment, encompassing the earth, water, and vegetation that grows upon it. Customary Law "Tanda" serves as a deterrent against the irresponsible actions of individuals who may engage in activities such as looting forests (tree felling), stealing the produce of others' crops, or even harvesting or reaping personal crops such as bamboo or coconuts before the commencement of "Tanda" without the permission of "Ine Tanda”. The consequences of such actions are severe, as elaborated upon earlier, involving the "Poke Sega" ritual.

The "Customary Law Tanda" holds an educational dimension passed down by ancestors to their descendants from generation to generation, emphasizing that theft is not virtuous. This lesson is conveyed through expressions such as: "Ngisa fucu bugu, peni wesi ma’e taku bhalo... Poa koka sedho ngisa aka gedho, manu kako negha na madho... Ngisa ae apu basa beru dapa ka, mo’o tau bo’o tuka ne’e yenga foko. Kungu ngisa fugu, logo ngisa una... gae jeka lia ae, kono jeka obo lowo..." (One must make efforts to cultivate and rear, avoid idleness, and rise early in the morning with the crowing of the rooster to seek a livelihood and sustain life).

The customary law of "tanda" is closely related to customary institutions because, in case of violations, these institutions carry out enforcement efforts. Based on the original autonomy of the village, the village has the authority to establish customary institutions under the village's indigenous rights as a community institution that serves to assist and collaborate with the village government in the administration of village governance. Firman Sujadi states that village customary institutions are community institutions formed by a specific customary law community within a legal jurisdiction with rights to property within that customary legal jurisdiction. These institutions are entitled and authorized to regulate, manage, and resolve various issues related to the village community's customs and customary laws that are in effect Sujadi (2016).

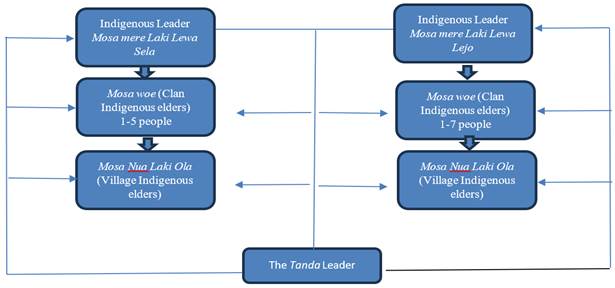

The indigenous legal community of Selalejo in both villages has two customary leaders known as Mosa Mere Laki Lewa. There is Mosa Mere Laki Lewa Sela, who oversees the indigenous legal community of Sela and leads several clans, each of which is headed by a Clan Leader (Mosa Woe/Ngapi). These clans can consist of only one village or multiple villages. Villages are referred to as "Nua" or "Nua Ola”, and within their institutional structure, there is a body known as "Mosa Nua Laki Ola”. On the other hand, the indigenous legal community of Lejo has its indigenous leader, Mosa Mere Laki Lewa Lejo, who shares a similar structure and function with the Sela indigenous legal community.

The two indigenous Leaders (Mosa Mere Laki Lewa) are based in the East Selalejo Village, which was administratively separated from Selalejo Village. The customary rituals and ceremonies are not performed simultaneously due to their dependence on the condition of cultural symbols, such as cultural artifacts like "Peo, Enda, Ana Ndeo”, which have aged and need to be restored. The process of reconstructing these cultural objects must be carried out through elaborate customary rituals, culminating in the "Pebha" ceremony. Pebha serves as a form of confirmation and formalization, granting cultural legitimacy, as it is during this ceremony that these cultural objects acquire religious and magical significance, regaining their cultural value and meaning similar to their original state. The ceremonial procedures for both the Sela indigenous legal community and the Lejo indigenous legal community are essentially the same. Historically, they are considered siblings but possess distinct powers, rights, and authorities specific to each indigenous legal community.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 The Institutional Structure of Sela and Lejo Indigenous Communities |

The commonly used term for all levels, including the Village leader, Clan leader, and Village Elders, can be referred to as "Mosa Laki", but their roles and positions vary. Regarding the existence and function of the Customary Institution depicted in the chart above, it is elaborated as follows:

1) Mosa

Mere Laki Lewa (Indigenous Leader)

The highest title conferred upon the Customary Chief, known as "Mosa Mere Laki Lewa," is understood literally as "Great Male." This title signifies the leader of the group or a collective assembly of Indigenous Community members. "Laki Lewa" means "a man with far-reaching and broad thinking or perspective." Therefore, "Mosa Mere Laki Lewa" refers to an individual with a broad and profound outlook who can provide guidance, embrace, and lead with wisdom and sagacity. The Customary Chief must possess authority and leadership qualities, and their selection is based on lineage. The term of office for an indigenous leader is a lifetime appointment.

Based on the structure depicted in the previous image, it is important to note that it does not represent a distinct social stratum within society. Instead, it functions primarily as a custodial or regulatory body within the realm of customary governance.

Mosa mere laki lewa is responsible for safeguarding the customary law and the cultural symbols or emblems of cultural significance (Peo-Enda) in the traditional village's central location. As the Head of Customary Affairs, he possesses a strong personality that enables him to provide wise, judicious, and democratic guidance to the members of the customary community when making decisions. Despite being selected based on lineage, he is not an authoritarian or arbitrary leader. Instead, he operates as a collaborative leader, symbolized by the Peo-Enda (a symbol of collective decision-making). Martinus Both Bhae, representing the traditional elders of Lejo, likened the Mosa Mere Laki Lewa (Head of Customary Affairs) to a mighty banyan tree, with its sturdy branches and lush leaves providing shelter for all (Nunu mere imu nda’a ta’a kelinegi, wunu imu tolo imu ndiu mo’o tau fall bao rebu yiwu bap) (Interview with Adrianus Nuga, leader of Nowa Elu Clan and Fanus Gunu, member of Nowa Elu Clan, 2022).

Mosa mere laki lewa sela supervises five clan leaders (Mosa Ghili), each serving as the elder within their respective clans. Similarly, Mosa Mere Laki Lewa Lejo oversees seven clan leaders (Mosa Ghili), who hold the role of elders within their respective clans.

2) Mosa

Woe (Clan indigenous elders)

Mosa Woe refers to a Mosa within the context of the indigenous customary law of the respective clan or the scope of Ghili Woe/Ngapi, or the related tribe. The indigenous customary community of Sela, under the leadership of Mosa Mere Laki Lewa, comprises five tribes, each headed by a Tribe Leader (Mosa Woe/Ghili Woe or Ngapi). The role of the Tribe Leader (Mosa Woe) involves managing, safeguarding, and preserving the tribal lands, along with the forests, plants, and crops on them. These clan lands and all associated flora and fauna are managed and utilized by the individual members of the tribe generation after generation, with their respective boundaries clearly defined.

The function of Mosa Ghili/Ngapi is to coordinate and resolve land disputes or boundary disputes among tribe members or between members of different tribes. An ancestral saying advises descendants to recognize and respect the rights of others and warns against shifting the boundaries of neighboring lands, as doing so could lead to illness and disease as a consequence. It is strictly forbidden to engage in such actions, referred to as "Pi Singi Laga Lange" or encroaching upon another's land. They acknowledge that the land represents the "Mother" composed of flesh and blood, and therefore, tampering with the land by violating the rights of others is deemed unacceptable (Interview with Adrianus Nuga, leader of Nowa Elu Clan, and Fanus Gunu, member of Nowa Elu Clan, 2022).

3) Mosa

Nua Laki Ola (Village indigenous elders)

Mosa Nua Laki Ola holds the position of Village Elder, and their role primarily involves resolving various issues or disputes within their respective villages before escalating them to higher authorities or involving formal government institutions or law enforcement agencies.

All matters related to moderate or severe criminal offenses should be brought to the formal judicial institutions, or in cases involving civil disputes where no resolution can be reached through the customary institutions at all levels, individuals are encouraged to take their cases to court if they feel aggrieved.

4) Ine

Tanda (The Tanda Leader)

"Ine Tanda”, who serves as the chairperson and executor of the "Tanda" for both the customary law communities of Sela and Lejo, is unified under a single individual or body chosen and entrusted by both customary law communities of Sela and Lejo.

4. CONCLUSION

From the perspective of the local wisdom of the Selalejo customary law community, the concept of "Tanda" proves highly effective in preserving the natural environment (earth, water, and plants) that grows and thrives upon it. Its philosophical foundation lies in the inseparable relationship between humans and the surrounding natural environment, as the earth and water represent the body and blood of humans, symbolized in the form of a mother figure (Mother Earth), upon which all plants and vegetation, including forests, flourish. Furthermore, various religions view the entire universe (earth, water, and the plants upon it) as the creation of the Almighty God. Humans are entrusted with the responsibility to govern this creation, which includes the duty to protect, preserve, and manage it responsibly, without acting arbitrarily.

The existence of the "Tanda" customary law as a code applicable to both customary law communities serves as a tool of social control and as an instrument for social behavior modification. It aims to rectify inappropriate conduct related to the irresponsible and arbitrary use of natural resources. In the event of violations against the "Tanda" customary law, its enforcement is carried out by customary institutions.

5. RECOMMENDATION

"Tanda" must be upheld as an effort for environmental conservation by the Leader of Customary Law (Mosa Mere Laki Lewa) and the hierarchy within the customary institutional structure, and it should be implemented by the entire community.

The Customary Institution, as a partner of the Village Government, collaborates with the Village Government and the Village Consultative Body (BPD) to propose a Village Regulation Draft regarding "Tanda" to have its legality recognized within the legal framework.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abdurrahman, M. (2009). Sosiologi dan Metode Penelitian Hukum. UMM-Press.

Ali, A. (1996). Menguak Tabir Hukum (Suatu Kajian Filosofis dan Sosiologis). Chandra Pratama.

Baratha, I. N. (1991). Pembangunan Desa Berwawasan Lingkungan. Bumi Aksara.

Budiyanto, M. E. (2013). Sistem Informasi Manajemen Sumber Daya Manusia. Graha Ilmu.

Kosmas, E. (2018). Pelimpahan Kekuasaan Pemerintahan Negara Dalam Hal Presiden Berhalangan Sementara. [unpublished doctoral Dissertation], Airlangga University.

Nasihudin, A. A. (2017). Kearifan Lokal Dalam Perlindungan dan Pengelolaan Lingkungan Hidup, studi Di desa Janggolan. Banjumas Jurnal Bina Lingkungan, 2(1), 99-10. https://doi.org/10.24970/bhl.v2i1.42.

Ranggawidjaja, R. (1998). Pengantar Ilmu Perundang-undangan Indonesia. Mandar Maju.

Soekanto, S. (1983). Hukum Adat Indonesia. Raja Grafindo Persada.

Soekanto, S. (1986). Pengantar Penelitian Hukum. UI-Press.

Sujadi, F. (2016). Pedoman Umum Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan Desa. Landasan Hukum dan Kelembagaan Pemerintahan Desa. Bee Media Pustaka. Jakarta.

Supriadi. (2014). Prinsip Hukum Pengelolaan Hutan Bakau Dalam Mewujudkan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan Berkelanjutan Di Indonesia, [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. Airlangga University.

Ter Haar, B. (1987). Asas-Asas dan Susunan Hukum Adat. Pradnya Paramita.

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© Granthaalayah 2014-2023. All Rights Reserved.