|

|

|

|

ENTREPRENEURSHIP AS A CATALYST FOR EMPLOYMENT: NAVIGATING THE UNEMPLOYMENT CHALLENGE IN LEBANON’S PRIVATE SECTOR

Saher H. El-Annan 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Hani M. Haidoura 2

,

Dr. Hani M. Haidoura 2![]()

![]()

1 Professor,

International American University, Lebanon

2 Central

Ukrainian National Technical University, Kirovohrad – Ukraine, Lebanon

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This study

shows the importance of entrepreneurship as a countermeasure, notably in the

private sector, against a backdrop of growing unemployment and institutional

failures in Lebanon. The main goal is to validate the link empirically and

intellectually between entrepreneurship and lower unemployment. The research

relies on primary data acquired via an internet survey and employs a

qualitative technique with an exploratory-descriptive design. This

instrument, which included a variety of question types, gathered information

from a broad group of 150 participants, including managers, entrepreneurs,

and the jobless, who were chosen using convenience sampling. The study's key

findings demonstrate that entrepreneurship reduces unemployment

significantly. It indicates three essential results, in particular:

entrepreneurship immediately reduces unemployment rates, it reduces

individuals' turnover inclinations, thus stabilizing employment, and it

promotes self-employment, further reducing unemployment pressures. These

findings not only highlight entrepreneurship's complex impact on employment

dynamics but also advocate for its potential as a strategic lever in alleviating

Lebanon's unemployment crisis. |

|||

|

Received 12 October 2023 Accepted 13 November 2023 Published 29 November 2023 Corresponding Author Saher H.

El-Annan, saherelannan@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/ijetmr.v10.i11.2023.1376 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Unemployment, Self-Employment, Turnover |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Unemployment remains a key global issue, having a significant impact on societies and governments, particularly in modern times. This situation does not only indicate a lack of job prospects for active job seekers; it also includes retired people, homemakers, students, and those who are unable to work. Unemployment has far-reaching consequences, producing societal issues such as crime, homelessness, bad health, and economic insecurity, among others Hill (2018).

Entrepreneurship, on the other hand, is a beacon of the economic revolution, defined as the process of starting and running a new company endeavour with related risks. Beyond generating profits, entrepreneurship promotes societal change by tackling important issues, frequently through the development of novel ideas, businesses, or markets. Despite scholarly differences about its classification, self-employment, a contentious subset of entrepreneurship, remains critical Urbano et al. (2019).

Entrepreneurship's worldwide significance is undeniable, given its contributions to human capital, sustainability, poverty reduction, and technical advancement. Institutions are now including social entrepreneurship in their curricula, preparing future leaders to address societal concerns inside their businesses. Entrepreneurship is widely recognized as a significant economic engine, and its influence on job creation and economic dynamics has been thoroughly researched. Judge & Robbins (2017).

This study departs from typical approaches by investigating the interaction between entrepreneurship and unemployment in various economic and social circumstances. Understanding this relationship, particularly through empirical investigation, provides genuine insights into the societal and economic implications of entrepreneurship. Country-specific entrepreneurial disparities highlight its importance in job creation Audretsch & Thurik (2004).

The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth and national development is well documented, with nations such as Brazil, South Africa, and India experiencing significant private sector growth as a result of entrepreneurial activity. Even in industrialized countries such as the United States, entrepreneurship is hailed as a driver of global economic competitiveness. Carayannis et al. (2020).

The entrepreneurship-unemployment nexus has received attention in the wake of high worldwide unemployment rates, with theories claiming that high unemployment motivates entrepreneurial activities. Increased entrepreneurial activity, on the other hand, is thought to boost employment and reduce unemployment Freytag & Thurik (2007). Surprisingly, entrepreneurship is associated with lower employee turnover, implying that, despite perceived insecurity, entrepreneurial firms provide greater job security. This stability results from the prevention of potential income loss and the psychological commitment of entrepreneurs.

In Lebanon, severe unemployment and poverty, worsened by political and economic turbulence, provide a bleak picture Government of Lebanon and the United Nations 2017-2020. (2019). With job creation falling far short of need, entrepreneurship and self-employment appear to be viable options. This research investigates the entrepreneur-unemployment dynamic in Lebanon's private sector.

1.1. Research Questions

What effect does entrepreneurship have on unemployment in Lebanon's private sector?

1.2. Research Objectives

· To examine the concept of entrepreneurship

· To investigate the phenomenon of unemployment

· To assess the economic consequences of unemployment

· To investigate the relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment in the context of Lebanon's private sector.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurship

Some scholars define entrepreneurship as dynamic, creative, and innovative venture creation. Others see it as self-employment. Academics define entrepreneurship as finding chances and gathering resources to start new businesses. It involves solving social issues with innovative ideas, enterprises, or markets Dollinger et al. (2018). Thus, entrepreneurs innovate or explore market prospects, taking risks to achieve aims. Entrepreneurship requires risk tolerance and willingness to face uncertainty, which economist Joseph Schumpeter called "wild spirits" destabilizing economies with innovative changes. Entrepreneurs use personal initiative to innovate or scale a firm, driven by opportunity, profit, skill development, and risk-taking to build or extend markets Dollinger et al. (2018).

Entrepreneurship is often seen as a risky job with high failure rates and income volatility. This study examines how entrepreneurship affects employment stability. Those with restricted work prospects may choose self-employment as an alternative, balancing unemployment, self-employment, and formal employment. While unemployment drives self-employment, it may reduce unemployment, according to controversial empirical findings Hwang (2021).

Employee turnover includes both voluntary and involuntary departures. Aspirations boost turnover intentions by increasing entrepreneurial self-efficacy and job happiness. Strong job embeddedness reduces turnover by moderating this effect. Entrepreneurship can increase or decrease turnover depending on job satisfaction, leadership quality, workplace inclusiveness, performance pressure, and self-confidence Åstebro et al. (2011).

2.1.1. Entrepreneurship Theories

Entrepreneurship philosophies have some themes despite their diversity. Entrepreneurs disrupt economies with creative and strategic activities that go beyond new products to improve processes and create new markets, according to the Innovation Entrepreneurship Theory Carayannis et al. (2015). Entrepreneurs are crucial to economic theory because they create and distribute goods and products and are at the heart of supply networks Brown & Thornton (2013). According to the Sociology of Entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial enterprises must fit social norms, traditions, and cultural structures to succeed Ruef & Lounsbury (2007). The Psychology of Entrepreneurship classifies entrepreneurs by their locus of control, personality qualities, and accomplishment motivation, making them a distinct professional group Frese & Gielnik (2014). The Resource-Based Theory states that successful entrepreneurship requires strategic acquisition and use of resources, including human and social capital Kuratko (2016). The Five-Phase Theory shows how entrepreneurial ventures evolve from stimulation to feedback, and how they mature non-linearly Kuratko (2016). Finally, the Theory of Income Choice, or Income and Employment Theory, guides government policy and strategy to stabilize the economy by focusing on macroeconomic dynamics including output, unemployment, and wages Kuratko (2016).

2.2. Unemployment

The OECD defines unemployment as actively seeking a job

but not finding it. Unemployment includes people awaiting job reinstatement

after dismissal but excludes those quitting job searches for education or

discouragement Abbott

& Teti (2017).

2.2.1. Types of Unemployment

Cyclical Unemployment: When demand drops during recessions, production, and personnel layoffs Pigou (2013).

Frictional unemployment: People switching jobs barely affect the economy. Job searching and market operations naturally produce it Pigou (2013).

Structural Unemployment: Mismatched skills and job needs, or geographical dislocations cause structural unemployment. The displacement of workers by technology also causes this sort of unemployment Pigou (2013).

2.2.2. Consequences of Unemployment on the Economy

The economic effects of unemployment extend beyond the individual. Personal financial pressures reduce consumer expenditure, which may cause recessions. Long-term unemployment can damage mental and physical health, skills, and the economy Hall & Kudlyak (2020).

High unemployment causes poverty, community decay, and social unrest. International commerce and economic growth may suffer from protectionist policies. Crime rates rise with unemployment, highlighting its social implications Hall & Kudlyak (2020).

2.3. Empirical Literature

2.3.1. Relationship between Entrepreneurship and Unemployment

Complex entrepreneurship-unemployment nexus. Some research implies that crises spur entrepreneurship, such as increased unemployment. However, the unemployed may lack entrepreneurial skills and funds Freytag & Thurik (2007).

Entrepreneurship may boost employment in "creatively destructive" economies. Entrepreneurs earn from innovations that lower production costs or increase consumer demand. According to empirical and theoretical frameworks, unemployment promotes entrepreneurship, which reduces unemployment Freytag & Thurik (2007).

This relationship is complex. Unemployment can spur self-employment, reducing unemployment. Economic downturns encourage the unemployed toward self-employment, while good periods offer strong marketplaces for entrepreneurs. Thus, unemployment and self-employment involve recession-driven necessity and prosperity-driven opportunity Audretsch & Thurik (2004). Turnover decrease is another factor. Due to psychological commitment and probable revenue losses when returning to salaried jobs, entrepreneurs have lower turnover rates. This stability contrasts with pre-entrepreneurial periods with increased turnover Failla et al. (2017).

3. METHOD

3.1. Research Methodology

This study employs a qualitative technique, which is ideal for an in-depth examination of the dynamics of entrepreneurship and unemployment in Lebanon's private sector. Unlike quantitative research, which seeks numerical data for statistical analysis, qualitative research dives into the complexities of 'how' and 'why,' using techniques such as focus groups and in-depth interviews to gain nuanced insights. Although detailed, this method has limitations in generalizability and necessitates careful consideration of the population scale for meaningful and reliable conclusions.

3.2. Research Design

The study design serves as a road map for data collecting, directing us toward reliable answers to our research questions. We picked an exploratory descriptive strategy from among many designs because of its applicability in exploring the complex relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment. This design works especially well when beginning with broad principles and eventually refining down to specific study areas, laying the groundwork for future in-depth studies.

3.3. Sampling Design

Because our research is qualitative, we used a non-probability convenience sampling technique. While convenient, this method picks participants based on availability and eligibility, which may introduce bias. However, it is especially useful for pilot studies or where there is little diversity in the population.

3.4. Data collection

The research relies heavily on primary data acquired through electronic surveys. These surveys, which will include a variety of question types, will reach a varied participant pool of 150 people, including managers, employees, entrepreneurs, and the unemployed. Though time-consuming and potentially costly to collect, this primary data provides unprecedented insights into the study's topic, providing legitimacy and precision to our conclusions.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Data Description

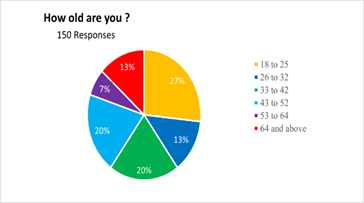

A random cohort from social media was given a twenty-question Google Forms survey and responded 150 times. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 25 (27%), while some were 64 and older. In Lebanon, 64 is the traditional retirement age, however, people often work past it. Using their experience, many seniors become entrepreneurs, consultants, or managers.

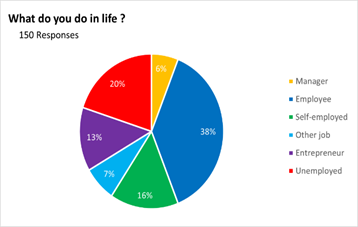

The poll respondents were diverse. The pool was 38% employed and 20% jobless, illustrating Lebanon's severe employment problem. There were 16% self-employed and 7% other workers, possibly contract workers. Entrepreneurs made up 13%, with 40% managing 5 to 10 staff, indicating modest business ownership. Another 35% had 30 or more employees, indicating medium-sized businesses. Around 15% ran family enterprises with 1 to 5 people, while 10% managed teams of 10 to 20.

The diversity of participants' ages and occupations may seem unrelated to the study's main focus, but it helps explain Lebanon's complex employment landscape, especially entrepreneurial ventures and unemployment rates.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Age Distribution of Respondents |

Figure 1 27% between 18 and 25, 13% between 26 and 32, 20% between 33 and 42, 20% between 43 and 52, 7% between 53 and 64, and 13% over 64.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Occupation Distribution |

Figure 2 Manager 6%, Employee 38%, Self-employed 16%, other job 7%, Entrepreneur 13%, and Unemployed 20%.

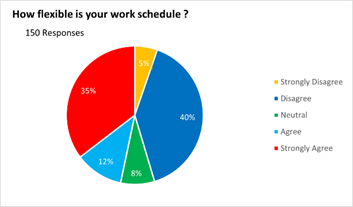

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 The Number of Employees Managed by Entrepreneurs |

Figure 3 1 to 5 15%, 5 to 10 40 %, 10 to 20 10%, and 30 and more 35%.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Work Schedule Flexibility as Felt and Rated by the Respondents |

Figure 4 Disagree 40%, strongly agree 35%, Agree 12%, Neutral 8%, and Strongly Disagree 5%.

Figure Job satisfaction.

Figure Disagree 34%, Strongly Disagree 27%, Agree 16%, Strongly Agree 15%, and Neutral 8%.

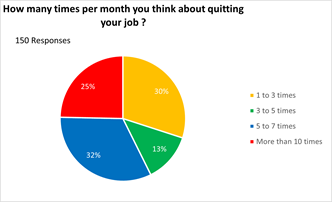

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Quitting Job Readiness/Risk |

Figure 5 Strongly Disagree 16 %, Disagree 15 %, Neutral 10 %, Agree 33 % and Strongly Agree 26 %.

According to survey respondents, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6 show work-schedule

flexibility, job satisfaction, and the likelihood of employees quitting. The

survey's unemployed participants may bias results. Their comments may

accurately represent employment discontent, a desire to leave (if previously

employed), or neutrality in work-schedule flexibility, exaggerating these

Figure 12, Figure 14, and Figure 16, obtained from linked

queries, may show similar tendencies. These data points could illuminate

employee turnover, unemployment rates, and job satisfaction, which are crucial

to understanding how entrepreneurship affects unemployment.

Questions 9, 10, and 20 offer additional nuances that

should be investigated in the data analysis section, even if they are not

directly involved in numerical and frequency analyses. These questions may

provide contextual information that, while not quantitative, helps explain the

job landscape and entrepreneurial activities.

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Workplace Climate as Described by Respondents |

Figure 6 People-oriented 27 %, Rule-oriented 18 %, Innovation-oriented 29 %, and Goal-oriented 26 %.

Figure 7

|

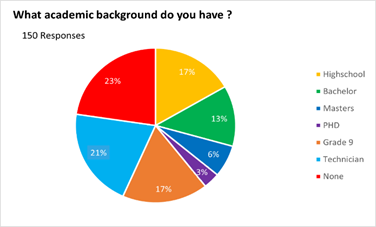

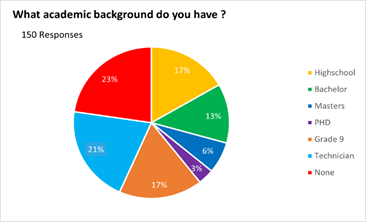

Figure 7 Academic Background |

Figure 7 Highschool 17 %, Bachelor 13 %, master’s 6 %, PHD 3 %, Grade 9 17 %, Technician 21 %, and None 23 %.

Figure 8

|

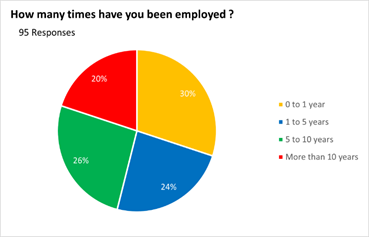

Figure 8 Years of Employment |

Figure 8 0 to 1 year 30%, 1 to 5 years 24 %, 5 to 10 years 26 %, and more than 10 years 20 %.

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Years Practising Entrepreneurship |

Figure 9 0 to 1 year 18 %, 1 to 5 years 25 %, 5 to 10 years 35 %, and More than 10 years 22 %.

Figure 10

|

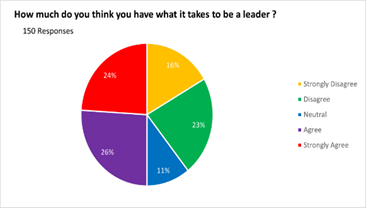

Figure 10 Leadership Skills in the Eyes of Respondents |

Figure 10 Strongly Disagree 16 %, Disagree 23 %, Neutral 11 %, Agree 26 %, and Strongly Agree 24 %. Note that the agree and strongly agree represent 50% of the answers and we will see why expectedly in the data analysis.

Figure 11

|

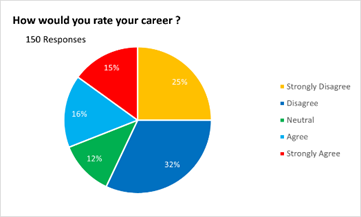

Figure 11 Career Rating by Respondents |

Figure 11 Strongly Disagree 25 %, Disagree 32 %, Neutral 12 %, Agree 16 %, and Strongly Agree 15 %.

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Leadership Practices |

Figure 12 The best orders accompanied by some supports are the best to follow 24 %, Training and coaching are not as important as guidance and good vibes are no good with such people 28%, And Guidance, clear orders and clear goals are as much important as support and coaching and with the right combination success is inevitable 48 %.

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Turnover Readiness |

Figure 13 Strongly Disagree 16 %, Disagree 15 %, Neutral 10 %, Agree 33 %, and Strongly Agree 26 %.

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 Necessity of Entrepreneurship |

Figure 14 Strongly Disagree 11 %, Disagree 14 %, Neutral 11%, Agree 31%, and Strongly Agree 33 %.

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 Readiness for Being an Entrepreneur |

Figure 15 Strongly Disagree 13 %, Disagree 15 %, Neutral 19 %, Agree 31%, and Strongly Agree 22 %.

Figure 16

|

Figure 16 Entrepreneurship and Effect on Turnover from the Perspective of Respondents |

Figure 16 Strongly Disagree 33%, Disagree 31%, Neutral 11%, Agree 14 %, and Strongly Agree 11%.

Figure 17

|

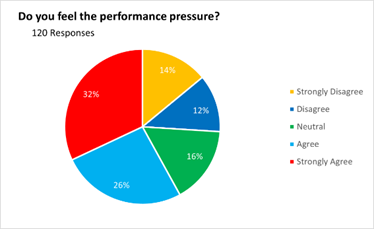

Figure 17 Performance Pressure Effect |

Figure 17 Strongly Disagree 14 %, Disagree 12 %, Neutral 16 %, Agree 26 %, and Strongly Agree 32 %.

Figure 18

|

Figure 18 Necessity of Performance Pressure |

Figure 18 Strongly Disagree 12 %, Disagree 12 %, Neutral 18 %, Agree 27 %, and Strongly Agree 31.

Figure 19

|

Figure 19 Career Path Satisfaction |

Figure 19 Strongly Disagree 23 %, Disagree 26 %, Neutral 12 %, Agree 21 %, and Strongly Agree 18 %.

5. Discussion

This complex link between entrepreneurship and unemployment has three main channels. First, entrepreneurship directly addresses unemployment by creating jobs and growing businesses Audretsch & Thurik (2004). Second, it encourages self-employment as people create their careers out of necessity or desire Audretsch & Thurik (2004). This self-employment boosts economic growth and reduces unemployment. Third, entrepreneurship affects work market dynamics, especially turnover. Entrepreneurship may initially increase job turnover, but its stability and fulfilment can later minimize it Failla et al. (2017).

The survey data, comprising 60% of respondents aged 18–42, highlights this demographic's importance in the workforce and entrepreneurship. The high unemployment rates in this age group demonstrate the importance of entrepreneurial efforts in reducing unemployment, even though Lebanon's diverse job landscape may not be entirely captured by the 20% rate. The data also shows a strong preference for entrepreneurship and self-employment as a response to unemployment and a search for better work. However, this trend highlights the complex effects of entrepreneurship on job satisfaction and turnover intentions, requiring a sophisticated explanation.

The Lebanese workforce is highly educated and specialized. The harsh economic condition in Lebanon presents substantial problems. The pervasive search for cash, especially in foreign currency, has made entrepreneurial endeavours appealing as a survival strategy and a possible solution to economic problems like rampant corruption.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

Entrepreneurship is a beacon of initiative and creativity that can help combat rising unemployment. This study examines the complex relationship between entrepreneurship and unemployment in Lebanon's private sector using qualitative and exploratory descriptive methods. Primary data from a convenience sample of 150 respondents supports the theoretical frameworks.

Entrepreneurship directly reduces unemployment, dampens turnover, and boosts self-employment, alleviating unemployment. These results support theoretical ideas and mirror survey members' lives.

While informative, the scope of this research suggests various future research directions. A larger, more diversified sample could improve generalizability. More research on mediating factors and the Lebanese crisis's background could improve comprehension.

In conclusion, entrepreneurship is a product and an unemployment remedy. Both theoretical and empirical data show that it's a complicated, dynamic force that can change employment. Its ability to create and reduce unemployment makes it crucial in economic and social situations, especially Lebanon's.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to convey our profound appreciation to the survey respondents, without whose candid comments this research would not have yielded the results it has. We also want to emphasize that this study received no outside financing, which demonstrates the collaborative spirit of academic inquiry and our commitment to shedding light on vital socioeconomic concerns.

REFERENCES

Abbott, P., & Teti, A. (2017). A Generation in Waiting for Jobs and Justice : Young People Not in Education, Employment or Training in North Africa. Arab Transformations Working Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3020728

Åstebro, T., Chen, J., & Thompson, P. (2011). Stars and Misfits: Self-Employment and Labour Market Frictions. Management Science, 1999-2017. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1400

Audretsch, D. B, & Thurik, R. A. (2004). A Model of the Entrepreneurial Economy. Papers on Entrepreneurship, Growth and Public Policy. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/19957

Brown, C., & Thornton, M. (2013). How Entrepreneurship Theory Created Economics. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=dbd1feb9fd1f52b59243a0d60c8b1105dd905d8e

Carayannis, E., Elpida, S., & Bakouros, Y. (2015). Innovation and entrepreneurship Innovation, Technology, and Knowledge Management. Springer International Publishing, 978-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11242-8

Carayannis, E., Jones, P., & Apostolopoulos, N. (2020). Entrepreneurship and the European Union Policies After 60 Years of Common European Vision: Regional and Spatial Perspectives. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 517-522. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2020.1769883

Dollinger, M., Lodge, J., & Coates, H. (2018). Co-Creation in Higher Education: Towards a Conceptual Model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 210-231. Retrieved from Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 28(2), 210-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2018.1466756

Failla, V., Melillo, F., & Reichstein, T. (2017). Entrepreneurship and Employment Stability-Job Matching, Labour Market Value, and Personal Commitment. Journal of Business Venturing, 162-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.01.002

Frese, M., & Gielnik, M. (2014). The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav, 413-438. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091326

Freytag, A., & Thurik, R. (2007). Entrepreneurship and its Determinants in a Cross-Country Setting. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 117-118-131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-006-0044-2

Government of Lebanon and the United Nations 2017-2020. (2019). Retrieved from Lebanon Crisis Response Plan: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/67780.pdf

Hall, R. E., & Kudlyak, M. (2020). The Inexorable Recoveries of our Unemployment. Bureau: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://ubcecon.github.io/2021CMSGVirtual/papers/Hall_Kudlyak_InexorableRecoveries_Posted.pdf

Hill, P. (2018). The Unemployment Services: A Report Prepared for the Fabian Society. Routledge, 7. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429470080

Hwang, K. (2021). Entrepreneurship as a bridge to employment? Evidence from formerly incarcerated individuals. Academy of Management, 15966. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2021.35

Judge, T. A., & Robbins, S. P. (2017). Essentials of organizational behaviour. US: Pearson Education. https://toc.library.ethz.ch/objects/pdf03/e01_978-1-292-09007-8_01.pdf

Kuratko, D. F. (2016). Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, and Practice. Cengage Learning. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305328732_Entrepreneurship_theory_process_practice

Pigou, A. (2013). Theory of Unemployment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203041536

Ruef, M., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Introduction: The Sociology of Entrepreneurship. In the Sociology of Entrepreneurship, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0733-558X(06)25001-8

Urbano, D., Sebastian, A., & Audre, D. (2019). Twenty-Five Years of Research On Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth: What has been Learned. Small Business Economics, 21-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0038-0

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© IJETMR 2014-2023. All Rights Reserved.