ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

edTHE VEDAS AND BHAKTI HARMONIZED - KOVALUR: THE MUTAL ALVARS AND TIRUMANKAI1 School of Tamil, Indian Languages and Rural Arts, Gandhigram Rural University, Gandhigram, India |

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Received 01 June 2021 Accepted 05 July2021 Published 17 August 2021 Corresponding Author R.K.K. Rajarajan, rkkrajarajan@yahoo.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v2.i2.2021.27 Funding: This research received

no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or

not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are

credited.

|

ABSTRACT |

|

|

|

The unanimous opinion among religious philosophers is

that the Vedas and bhakti are two different denominators of approach to God

in Indian tradition. However, the Tamil Vaiṣṇava

mystics, the Āḻvārs find a

harmonious blend of the two modes in ritual worship. The present article

examines the pros and cons of the problem from a study of the hymns beginning

with the Mutal (Early) Āḻvārs

and last in the train, Tirumaṅkai. The cited

hymns are replete with the bounties of nature associated with the divyadeśa-Kōvalūr that we examine for a

case study. Bhakti or the Veda is the euphony linked with nature. The present

article explains how the Āḻvārs had

harmonized the Veda with bhakti. These are complementary modes of approach to

God. They are not conflicting phenomena. By the way, data bearing on flora

and fauna dumped in the twenty-one hymns on Kōvalūr

are presented in a capsule (Attachment). |

|

||

|

Keywords: Mutal Āḻvārs

(Poykai, Pūtam, Pēy), Tirumaṅkai, Veda,

Bhakti, Nālāyirativviyappirapantam

‘Nālāyiram’, Flora and Fauna 1. INTRODUTION

Nīrār nīrār “Who are you, who are you?”[1] Aham Brahmāsmi “I am Brahman” Amararum yāṉē “I am the gods”[2] It was thundering, lightning, and torrentially

raining under the spell of an encircling gloom. Three mystics, the Mutal (Early) Āḻvārs

(viz., Poykai, Pūtam,

and Pēy Figure

4 hastily moved to a dark chamber in the Viṣṇu-Trivikrama temple at Kōvalūr seeking shelter. Poykai

(literally “Pond”) of Kāñci arrived first in

the iṭaikkaḻi that found space for him

to sleep. The next to arrive was Pūtam

(“Goblin”, also “Truth”) of Kaṭal-Mallai so

that the two could sit in the room. Finally came Pēy

(“Devil”, also “Frenzy”) of Mayilai/Allikkēṇi, and all three were standing. The Āṟāyirappaṭi-G adds the three met

in the tiru-iṭaikkaḻi of the temple.

Did they pose the question: nīrār nīrār? The mystics introduced formally saying

they are bhagavatśeṣabhūtas (cf.

the name Pūtattāḻvār, Pūtam = Bhūta). When

the three were standing, the presence of a fourth divinity was felt. It was

none other than Viṣṇu, the presiding

God of the divyadeśa (divya

“holy”, deśa “land”), ‘Ulakaḷanta Perumāḷ’

(cf. Trivikrama of Ūrakam)

that commended them to commence the saga of Vaiṣṇava

hymnal composition. The saints were inspired with a phrase each to begin

their work that forms part of the first verse in Tiruvantāti I, II, and III[3]. |

|

||

The Āṟāyirappaṭi-G adds the world was immersed in ajñāna (darkness, avarice leading to terrorism). The Lord appeared to light the lamp of bhakti (devotional reformation). Thus, the tivviyappirapantam/divyaprabandha (literally “divine twine”) came to be composed by the twelve Āḻvārs. U. Vē. Vēlukkuṭi Krishṇaṉ, in his popular lectures on the divyadeśas, adds Viṣṇu is the sugarcane of which the juice is the three Tiruvantātis. Furthermore, His Holiness Aṇṇagarācārya declares ‘Tirivikiramaṉ’ (Figure 6, Figure 7)[4] is the favourite theme of the Mutal Āḻvārs (cf. TI 1-2, Rajarajan et al. (2017b): 1428).

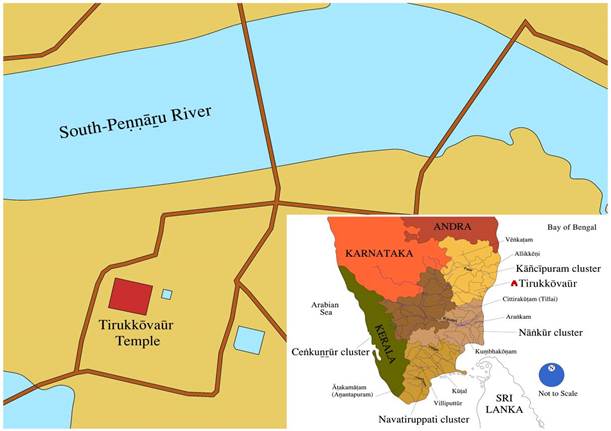

Kōvalūr (Figure 1 Map, Hardy (2014): Map 2) from the above account seems to be the earliest venue where the Āḻvārs commenced the composition of devotional literature in a Drāviḍian language[5]. For the historical cross-currents of the divyadeśas, we have a long list of literature, e.g., Hudson (1980), Hardy 1983, Young (2000), Narayanan (2007), Rajarajan (2012), Rajarajan (2013), Kalidos 2016, and so on. The concern of the present article is to examine the part played by Kōvalūr in the history of South Indian Viṣṇuism. The venue, Kōvalūr, appears in the hymns of Āḻvārs Poykai, Pūtam, and Tirumaṅkai (c. 6th-7th to 9th centuries CE), missing in Pēyāḻvār. The total number of hymns is twenty-one, most of which are by Tirumaṅkai (Figure 5). It might suggest a temple existed (Figure 3) at the time of the Mutal Āḻvārs by about the 6th-7th century CE (Hardy (2014). It acquired wider popularity during the time of Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār, contemporary of Nandivarmaṉ Pallavamalla (731-796 CE) that has authored most hymns bearing on the divyadeśas in the Toṇṭaināṭu region Rajarajan (2013), i.e., the Pallava country Kalidos 2016. Most of the existing structures in the temple are the result of evolution over a millennium down to the 17th century CE Ragunath (2014), figs. 30-40, 102, 104-106, 109, 113-114, 123-125, 135, 137-140, 188).

The present article hopes to summarize the hymns bearing on Kōvalūr, focusing on the bhakti and Vedic modes of approach to God. As we understand from the hymns of Tirumaṅkai, the mystic has strived to bridge the Vedic mode with bhakti. A summary of the hymns is presented, followed by an analysis of religious systems and philosophies. Scholars interested in the Roman transcription of the hymns and patavurai (word to word or phrase to phrase meaning) may consult Rajarajan et al. (2017a). Few hymns in Romanized format may of help to compare the Sanskritic usage vis-à-vis their Tamil equivalents.

2. Rèsumè of the Hymns

2.1.

Tiruvantāti I (Poykai Āḻvār)

77. “The abodes (of the Lord) are Vēṅkaṭam, Viṇṇakar, Veḥkā and the venue of flower gardens Kōval[ūr], the gold-city. In these four venues, the Lord is present in standing, sitting, reclining, and walking modes. Those that mention the names of the venues are relieved of troubles in their life.”

86. “The Lord

with Śrīdevī arrived at the venue to

the hill-Govardhana and protected the cows from rains

(Periyāḻvār Tirumoḻi 3.5.1-11). They

neither got in nor get out but stationed close to the threshold at the flowery

venue*, Kōval.”[6]

* Later Svarga-vācal opened once in the year on Vaikuṇṭha-ekādaśi

day, month Mārkaḻi

(see Tiruppāvai

1, the Gītā

10.35 māsānāṃ Mārgaśīrṣo’haṃ)

see note 3.

Tiruvantāti II (Pūtattāḻvār)

70. “The hearts of devotees are full of the presence of the sacred venues where the Lord resorts for play. The divyadeśas are Tañcai, the foremost Araṅkam, Taṇkāl, hill dear to the Bhāgavatas Vēṅkaṭam, the Ocean of Milk, the great Mallai, Kōvalūr, fortified Kuṭantai/Kuṃbhakoṇam and above all the mind of the devotee.”

Periya Tirumoḻi (Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār)

2.4.1. “That day the Lord was pleased to unite with the damsel of the cowherds, Nappiṉṉai[7] and the lady on a lotus flower, Śrīdevī. He was a merciless taskmaster of terrorists. The abodes where the Lord is pleased to present are Naṟaiyūr gifted with vast groves and floods abundantly flowing sacred Āli, Kuṭantai and the city of ponds, Kōval and Nīrmalai. These are the venues where the Lord is pleased to stand, sit, repose, and walk.”

2.10.1. Mañcāṭu varaiyēḻum kaṭalkaḻeḻum vāṉamum maṇṇakamum maṟṟumellām Eñcāmal vayiṟṟaṭakki yāliṉmēlō riḷantaḷiril kaṇvaḷarnta vīcaṉṟaṉṟaṉṉait Tuñcānīrvaḷamcurakkum Peṇṇai[8]tteṉpāl tūya nāṉmaṟaiyāḷar Comucceyyac Ceñcāli viḷai vayaluḷtikaḻntu tōṉṟum tirukKōvalūraṉuḷ kaṇṭēṉ nāṉē*[9]

* Redundant in all hymns: “I have seen the Lord

at sacred Kōvalūr”.

“The seven mountain ranges (Kulaparvatas), the seven oceans, the vast sky (Milky Way), the earth-world and all other cosmic installations are contained in the sacred stomach of Vaṭapatraśāyī that reposes on a leaf of the banyan tree, ālilai/vaṭapatra. The Lord has not left out anything. The immaculate Caturvedis are chanting the Sāmaveda on the southern Peṇṇai River (Figure 2). Everywhere ripe paddy crops are found proclaiming the prosperity of the land.”

2.10.2. Kontalarnta naṟuntuḻāy cāntam tūpam tīpaṅkoṇṭamarar toḻap paṇaṅkoḷ pāmpil Cantaṇi meṉmulai malarāḷ taraṇimaṅkai tāmiruvaraṭi varuṭumtaṉ maiyāṉai Vantaṉaicey ticaiyēḻāṟaṅkamaintu vaḷarvēḷvi nāṉmaṟaikaḷ muṉṟutīyum Cintaṉaicey tirupoḻutu[10] moṉṟuñcelvat tirukKōvalūrataṉuḷ kaṇṭēṉ nāṉē

“The celestials carry fragrant holy basil, sandalwood, incense, and lights to offer worship. The Lord is reposing on the hooded serpent. The maid-Śrī of soft-breasts anointed with sandal-paste and the earth-maid (Bhū) gently massage the feet. The Lord is offered worship by tuning the seven musical notes, following the six Vedāṅgas, five sacrifices (Figure 8), recital of the four Vedas, and cultivating the triple fires. These are incessantly performed day and night. I have seen the prosperity assuring dignitary, Varadarāja at sacred Kōvalūr.”

2.10.3. “In a pond abounding with flowering plants, a demonic crocodile had caught hold of the elephant’s leg by its sharp teeth. The Lord appeared in the sky to confer grace and lifted the disc to redeem the suffering mammoth, Gajendra. See, the blue lily emerging from water shows the hue black. The Alexandrian laurels are shining like pearls in reddish-golden buds. Vibrant lotus flowers are projecting as lamps in pools full of water.”

2.10.4. “To cause the fall of Mālī, the Lord Rāma had to stage a battle. His customary operation is to arrive seated on the Garuḍa-vāhana Parthiban and Rajarajan (2016) to redress the gods’ grievances. He is the panacea for Bhāgavatas that shed tears under the impulse of devotion. In the groves therein, you find flowers of ironwood, gamboges, and blossoming common bottle. The swarms of striped beetles are generating sweet music to exhilarate the atmosphere. Sweet sugarcane plants have mushroomed in watery fields.”

2.10.5. Karaivaḷarvēl Karaṉmutalākak Kavantaṉ Vāli kaṇaiyoṉṟiṉāl maṭiya vilaṅkaitaṉṉuḷ Piṟaiyeyiṟṟu vāḷarakkar cēṉaiyellām peruntakaiyōṭutuṇitta pemmāṉṟaṉṉai Maṟaivaḷarap pukaḻvaḷara māṭantōṟum maṇṭapamoṇṭoḻiyaṉaittum vāramōtac Ciṟaiyaṇainta poḻilaṇainta teṉṟalvīcum tirukKōvalūrataṉuḷ kaṇṭēṉnāṉē

“The Lord Rāma was pleased to extirpate the race of terrorists represented by Khara, Kabandha, Vāli, et alii by the shot of an arrow Rajarajan (2015), Figure 1). The operation included emasculating the demons’ race with teeth protruding as a crescent and their chief, Rāvaṇa. The peace assuring Vedic scriptures[11] recited in each household, in pavilions (Figure 9)[12] meant for cultivation of the Vedas, in groves near brooks where the gentle breeze moves, and in all inns without fail.”

2.10.6. “Kṛṣṇa was intelligent enough to detect the butter stored in pots tied to the roof of the huts of milkmaids. He was pleased to dine his share when caught red-handed by Yaśodā. He was tied to a mortar where the little-Master, Dāmodara, stood as a black elephant. His eyes were brimming with snowy tears. The “lady on flower attended him”, Lakṣmī, along with the “lady of eloquence”, Sarasvatī, and the eight-armed “lady of the buck-vehicle”, Durgā[13]. All are present in the shining maṇimāṭam “bell-tower” temple.”

2.10.7. “Kṛṣṇa had to take to task the war-elephant, Kuvalayapīḍa. He smashed the snaffle of the horse-demon, Keśi. The seven bulls of fine breed were dislodged[14]. He pulled down the Queen’s flower trees, Yamalārjunabhaṅga; and shattered the wheel-demon, Śakaṭāsura. He finished the wrestlers, Muṣṭikāsura and Cāṇūra. The little-Master was mandragora Alexander (1965) to the craftsman of all these devilish machinations of Kaṃsa. The black areca trees yield green shoots from which white pearls scatter, shining as emerald and coral. The pear tree has produced golden buds in the honey pouring groves.”

2.10.8. “To relieve the earth from the burden of misrule, Kṛṣṇa was sent a dūta on the eve of the Bhārata War. He served as sārathi of Arjuna to resist the mighty army. The pride of the enemies, ruined in the Great War. The venue we resort to is the equal of devaloka, where the master of the single-bull, Śiva, Kubera, Indra, and the four-faced Brahmā are present. Several experts in the Vedas are busy with their avocations.”

2.10.9. “The Lord is a garden of the kalpaka trees united with the Goddess of the Earth, Bhū and the Lady of rank seated on the flower, Śrī. The disc and the conch are beaming on either side. He is inclined to bless those that unite with him. The sacred image is molten gold, hemavigraha, endowed with crimson feet, handsome hands, red lips, and yellow garments. Śiva and Brahmā are waiting to have a darśana.”

2.10.10. “Lord Black was pleased to redress the miseries of the devoted elephant-Gajendra. He is the blue, emerald akin to the hue of the rain-drenched cloud. His abode is full of optimistic experts in the Holy Scriptures. These hymns bearing on ‘I have seen the Lord at the auspiciously sacred Kōvalūr’ are the words of the king of Maṅkai-city. The experts in the ten hymns of the gladiator-Kaliyaṉ[15] are sure to obtain liberation from mundane bondages. They are blessed to have a darśana of the omnipresent Lord.”

7.3.2. “As a calf thinks of its mother; I am persuaded to follow the Lord. The Patriarch is merciful Benedictine. His mouth that day swallowed and vomited the world, Viśvarūpa. His ears fitted with makarakuṇḍalas. the youth rushed to the courtyard of fortified Kōvalūr when the Mutal-Āḻvārs were bewildered. The bull of a lion among the celestials, my beloved; I know the Lord only, none of the other paradevatās”.

7.10.4. “Our Lord is the little-Master, Kṛṣṇa that sucked forth the soul of the ogress-Pūtanā. He is the Māya worshipped by the clear-minded philosophers, sages, and seers. He is the youth that appeared to enlighten the Mutal Āḻvārs in the iṭaikkaḻi of fortified Kōvalūr. He is the Supreme God that governs the thoughts of the experts in the Vedas. The immaculate magnifying Light, Jyotisvarūpa. He is the horde that assures prosperity full of gold and gems if a devotee is impoverished. I went in search of the Lord and found Him at the holy land, Kaṇṇamaṅkai in the Kāviri estuary.”

Tiruneṭuntāṇṭakam (Tirumaṅkai)

6. “The king of gods, Trivikrama’s long hand, varadamudrā confers benevolences on devotees. He is the sole master of the bird-Garuḍa endowed with suparṇa. He admonishes demons and shows no mercy. Sing the praises of venues where the Lord’s feet are set. The River Peṇṇai (Figure 2) is forcefully inundating bunds. It is dragging bamboo plants that pour pearls, move into fields yielding gold. Kōvalūr[16] is a venue full of flowering ponds. My mind, do pay reverence to the Lord and the venue.”

7. “Lord Paraśurāma lifted his graceful battle-axe to extirpate the race of kṣatriyas. Lord of the earth, his lance pierced the ocean projecting with hills (creation myth of Kēraḷa?). It is the city of the Lord that exhibited his heroism by wielding the axe. The chaste maiden, Durgā, is the protector of the city who hails from the Vindhyas[17]. The city is full of groves, long and wide streets, and lotus ponds all along the pathways. The ruler of the hills, Malaiyamāṉ,[18] is offering homage to the Lord in the flowery venue at Kōvalūr. My mind is pleased to visit the venue.”

17. “The love-sick girl’s[19] soft breasts are beaten to acquire the hue of gold. She is prepared to elope and get away from her troublesome mother with tears bubbling in fish-like eyes. She listens to the cryptic languages of doves that they talk to their mates. She is deeply engrossed. She starts singing the glories of Taṇkāl and cold-Kuṭantai and listens to the musical recitals on Kōvalūr. Looking at her fantasy, the mother enquires, ‘is my girl befitting our house’s status?’ On hearing these words, she starts extolling the fame of Naṟaiyūr.”

The Ciṟiya Tirumaṭal (69) and Periya Tirumaṭal (123) of Tirumaṅkai

Āḻvār make a note of ‘Kōvalūr’ and Kōvalūr maṉṉum iṭaikkaḻi[20] yemmāṉ (my Lord resorting to the iṭaikkaḻi

of Kōvalūr).

Though Tirumaṅkai is the last[21]

to follow others, his hymns are of great value to single out the mode of

inviting the Lord in ritual worship, i.e., the Vedic and bhakti Czerniak-Drożdżowicz (2014). The two-way

process gets stabilized in the Mahābhārata, e.g., Viśvāmitra

conducting the yajña

Rajarajan 2015c and the Viṣṇusahasranāma

piously uttered by Bhīmācārya. Again,

the Buddhists, Jains, and certain later medieval sectarians, e.g., Vīra-Śaivism, did not accept the brāhmaṇical imposition of the Vedas[22].

It seems the Āḻvārs strived to

compromise bhakti, the Vedas and yajñas[23].

Bhaktimārga

T.M.P.

Mahadevan (1976: 18-19) has stipulated the modes by which bhakti is expressed: śravaṇa, kīrtana, smaraṇa, pādasevana (the Bhāgavatas

called Aṭiyār cf. Kalidos

2017b: 127), arcana, vandana, dāsya, sakhya, ātmanivedana

and so on. Visiting the holy centres by

walk (cf. Nātamuṉikaḷ in Āṟāyirappaṭi

pp. 115-121)[24];

extolling the Praise of the Lord, listening to the līlās Narayanan (1995) told in the purāṇas (retold in the

Paripāṭal

and the Cilappatikāram)[25];

worship by offering fragrant holy basil, sandalwood, incense and

perpetual lamps (nontāviḷakku

ARE 1900, no. 116)[26]; fervent devotion and emotionalism,

tears spontaneously overflowing (Periyāḻvār

Tirumoḻi

3.6.3); shower flowers (puṣpāñjali,

pūppali

in Cilappatikāram

28.231), recite the nāmāvalis[27],

petitions submitted to the Lord for absolution from sins accrued during human

births, karma, and saṃsāra,

and to reach the Lord’s abode in the Vaikuṇṭha.

God realized through bhakti, yoga[28]

, or bhoga[29]

as it is amenable to the devotee (cf. the Gītā, chap. 12 on Bhaktiyoga).

The līlās

and māhātmyas

retold in the hymns bearing on Kōvalūr are

rooted in the Harivaṃśa

and Viṣṇu Purāṇa,

and the regional Tamil redactions[30]:

the Lord is in seated, standing, reclining, flying or walking modes Kalidos (1999): 226, Figure 5); the Lord is dear to Nappiṉṉai, Śrī,

and Bhū[31];

Viśvarūpa, Vaṭapatraśāyī,

the butter-stealer, Dāmodara; Govardhanadhāri; Gajendra-mokṣam; vadham of Kuvalayapīḍa,

Pūtanā, Śakaṭāsura,

Keśi, Kaṃsa-,

dislodging Muṣṭikāsura and Cāṇūra, bull-fight to take the hand of Piṉṉai, Garuḍa-vāhana, Pāṇḍava-dūta, Pārthasārathi;

Kṛṣṇa the cute and handsome, sarvalakṣaṇalakṣaṇyaḥ

(VSN-360); gopī-nāyaka

Veṇugopāla; Paraśurāma-garvabhaṅga, Rāma admonishing Khara,

Kabandha, Vāli et alii; and terrorists of Laṅka (Rajarajan (2016)), and above all the Lord is Varadarāja, King (giver) of the most excellent

Paradise.

Vedic Rituals

Several

Vedic rituals are recorded in the hymns, which the south Indian rulers seem to

have adopted since the few centuries before the Common Era. Kings of the Caṅkam Age (c. 250 BCE to 250 CE)[32]

were credited with a name such as Palyākacālai-mutukuṭumip-peruVaḻuti

(the Pāṇḍya performing several Vedic

sacrifices) and Irācacuyam-veṭṭaperunaṟ-Kiḷḷi

(the Cōḻa performing the rājasūya).

The righteous Caturvedis are nurturing the Sāmaveda on the southern bank of the River Peṇṇai in the sacred venue at Kōvalūr (PTM 2.10.1). Sāmaveda in this verse is Cāmu, Somaveda, according to PVP.[33] But for the intonation, no much difference between reciting the Vedas and sahasranāmas may be detected. The vital idea is to extol the Praise of the Lord; let that be Māl/Kṛṣṇa or Viṣṇu and Indra or Varuṇa. Sectarians may claim, it should be performed only by the vaidīka[suddha]-brāhmaṇas (Rajarajan et al. 2017b: 1516); cf. the vaṭakalai approach and Śrī Rāmānuja permitting the non-brāhmaṇas to utter the aṣṭākṣara (Rajarajan 2015c citing the Tirumālai [vv. 39, 42-43] of Toṇṭaraṭippoṭi Āḻvār) resulting in vaṭakalai-teṉkalai schism.

The Vedic scriptures were recited in households and

pavilions meant to cultivate the Vedas

in groves near pools or brooks. The breeze was moving to generate a serene

atmosphere. The Vedas chanted

endlessly to facilitate cosmic harmony (PTM 2.10.5, cf. Rajarajan

2015c: 140-42), inviting rains by way of Varuṇa-japa (cf. Tiruppāvai 3-4). Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār

adds the recital took place within temple, possibly the garbhagṛha, the priests

spelling the Vedic intonation (divyadeśa-Cempoṉceykōyil in Nāṅkūr cluster); ceñcol nāṉmaṟaiyōr Nāṅkai naṭuvuḷ

Cempoṉcey-kōyilinuḷḷē

(PTM 4.3.7). Tirumaṅkai though a kaḷḷaṉ

by birth (robber by jāti/cāti

noted in Tiruvāymoḻi

3.5.5, 3.7.9, 3.4.3-4) adds the Veda

is the illuminating Lamp[34]

‘Vēta-nal-viḷakku’, and the tilaka of the

south ‘teṉ-ticait-Tilatam’ (PTM 4.3.8, 4.8.8).

The Lord is singularly unique whom the Vedas

could never discover, nāṉmaṟaikaḷ tēṭi eṉṟum kāṇamāttāc

celvaṉ (PTM 4.8.7).

The Lord is offered worship by tuning the seven musical notes (saptasvaras[35] cf. Rajarajan (2017), Figure 1), chanting the four Vedas[36], examining the six Vedāṅgas[37], conducting five sacrifices (Figure 8)[38], and invigorating the triple fires (cf. PTM 2.10.2, 3.8.4, 3.10.7, 4.2.2)[39]. PTM (4.4.8) includes kēḷvikaḷum, i.e., itihāsa-purāṇas (PVP) involving questions and answers. These were incessantly performed day and night, a clear pointer that in addition to stimulating the bhakti-oriented rituals, the Vedic offerings took place simultaneously. This compromise should have been initiated to satisfy both the groups of priests that had given room for differences of opinion on ritual code Stietencron (1977): 126-38 and Czerniak-Drożdżowicz (2014) Today in temples, both the parties co-exist (cf. PTM 2.10.2), one reciting the Vedas and the other reciting the Tamil pirapantam in key-centres of Viṣṇuism such as Veṅkaṭam, Śrīraṅgam, Śrīvilliputtūr[40] (Figure 9) and so on. The counter-reformation within Viṣṇuism. Even then, the two parties are rebellious at times on trivial matters such as whether the temple elephant should be graced with “v” or “u” type of ūrdhvapuṇḍra[41] (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7). A few scholars have a big issue with deciding whether a temple is vaṭakalai or teṉkalai oriented Kalidos (2015a): 137-39).

Tirumaṅkai was great among the Indian mystics, the coadjutor of Nammāḻvār. The later medieval bhakti savants (Nāmadeva, Mīrābāī, Jayadeva, Kabīr et alii followed the footsteps of the Tamil mystics Brockington (1996), chap. 8. The naked fact is that Nammāḻvār and Tirumaṅkai were not brāhmaṇas[42] but were experts in the Vedic lore. Their contribution to Tamil bhakti literature constitutes nearly 2/3 of the ‘Nālāyiram’. They were not prejudiced by modern politics-oriented ideas such as regional chauvinism, linguistic fanaticism, religious bigotism, and caste disparity. The Āḻvārs were universal in outlook to facilitate Cosmic Harmony. They wanted to see the world a paradise and not a den of devils; cf. the long list of flowering plants over-spilling with nectar (see Attachment), symbols of “Universal Religion” (Gallico 1999: fig. pp. 52-53). The Āḻvārs were vociferously lovers of the bounty of nature. They wanted man to live in peace with nature and assure fellowship for “beauty of the world and the paragon of animals” (Shakespeare: ‘Hamlet’ II, ii). “Love thy neighbour as thyself” should be the message adumbrated in any inter-religious platform. Let us not propagate “vain wisdom and false philosophy” (Milton: ‘Paradise Lost,’ II, 265).

The Mutal Āḻvārs showed the way to Tirumaṅkai to propagate the philosophy of “Universal Love”. The mūlabera in the Kōvalūr temple is Trivikrama assuring peace and prosperity for the Cosmos. A hymn from Āṇṭāḷ (Tiruppāvai 3) may be cited to this effect.

Ōṅki yulakaḷanta uttamaṉ …

Tīṅkiṉṟi nāṭellām tiṅkaḷ

mummāri peytu …

Nīṅkāta celvam niṟaitēlōr

em pāvāy (cf. PTM

7.10.4)

His Majesty that grew taller and taller …

Let the rains shower thrice a month unfailingly

…

We are promised the Paradise of everlasting

peace and prosperity

Attachment

Euphony of Nature

Scholars

have examined how nature and religion interplay where God’s presence is felt Kramrisch (1976) cited in Rajarajan (2016b), 84-85, Parthiban and Rajarajan (2016), Figure 1). The way that the Āḻvārs taste, cuvai, God, and enjoy nature is

quite natural. I am just listing the abundant data charted by the Āḻvārs in about twenty hymns. The venue, Kōvalūr, is set on the southern bank of the River

Peṇṇai. Naturally, riverside regions are

plenty in water, rich in agricultural fields (paddy in Tamilnadu

Figure 2)[43],

flora, and fauna making up the cradle of civilizations. Many flowering plants

and trees are flourishing on the venue that makes it the Garden of Eden Gallico 1999 a case for Taylor (2013): 239) “aborphilia”.

Birds and bees fly freely, relieved from the molestation of camouflaged jungle

monsters (when we write today [15 September 2017], the TV announced the

bombardment of a metro rail station in London). L’homme est né

libre, et partout il est

dans les fers: the good job the terrorists could

do to undo environmental resources!

I am

just presenting a catalog of flora and fauna and

related data appearing in the cited hymns.

|

TI 77 |

Pūṅ-kiṭaṅku “repository of flowers (flowering

groves)” |

|

TI 86 |

Pūṅ-Kōval “Kōvalūr

decorated with flower (gardens[44])” |

|

PTM 2.4.1 |

Taṭam “perched Indian linden”, Grewia microcos |

|

PTM 2.10.1 |

Iḷantaḷir tender leaf of āl/vaṭa

Ficus bengalensis (Wilkins

(2000): 469); ceñcāli (cf. PTM 4.1.6,

4.2.4) a greater variety of paddy (Figure 10) |

|

Ibid. 2 |

Tuḻāy: tuḷaci “holy basil” Oscimum sanctum (Wilkins

(2000): 470-72); cāntam sandalwood |

|

Ibid. 3 |

Malarccōlai “flower garden”; karunīlam “blue water-lily” Nymphaea stellata, puṉṉai “Alexandrian laurel” Calophyllum inophyllum, kamalam “lotus” padma (Wilkins

(2000): 459), a tropical plant and

flower, lotos in Greek and Deutsch, Egyptian water lily |

|

Ibid. 4 |

Karumpu “sugarcane”, curapuṉṉai

“Gamboge” Ochnocarpus longifolius,

vaṇṭu

“beetle.” |

|

Ibid. 5 |

Poḻil “grove” (Rajarajan

(2016b): 85-86); teṉṟal “enchanting

breeze”, the northern wind is cold-tormenting and the southern breeze the

food for love (Maturait teṉral vantatu kāṇīr

“see, the breeze of Maturai has come” Cilappatikāram

13.132) |

|

Ibid. 6 |

Kaḷiṟu “male elephant” (piṭi

“female elephant” PTM

1.2.3, 2.4.8), paṉi

“mist”, Malar-makaḷ

“Lady of rank on flower” (Lakṣmī), padmajā; kalai “buck.” |

|

Ibid. 7 |

Kari “elephant”, pari

“horse”, viṭai “bull”, marutam

Queens’ flower tree Terminalia arjuna, kamuku

“areca-nut” Areca catechu, pāḷai Spathe

or pericarp of palms (Tamil Lexicon V, 2638), pālai

“ivory wood” Wrightia tinctoria, muttu “pearl” *, marakatam

“emerald”, pavaḷam “coral”, cerutti Ochna squarrosa, moṭṭu “(flower) bud”, tēṉ

“honey”, cōlai “grove.” * For the past two millennia, ‘Italiano signore’

are crazy after perla collana! |

|

Ibid. 9 |

Pūmaṅkai “Lady of the Flower” (Lakṣmī), caṅku

“conch-shell”, kaṟpakam kalpaka-tree,

cempoṉ “molten gold” |

|

Ibid. 10 |

Vaṛaṇam “elephant” (Nācciyār Tirumoḻi

6.1), maḻai

“rain” (malai

“hill” PTM 1.5.1, 7.1.3) |

|

PTM 7.3.2 |

Makaram mythical fish (makarakkuḻai/makarakuṇḍala),

ari “lion”, ēṟu

“bull” |

|

PTM 7.10.4 |

Pey “devil”, ghoul, mutalai “crocodile”, maṇi

“gem” (cf. navaratna) |

|

TAN 6 |

Añciṟaip-puḷ suparṇa-bird (Garuḍa),

vēy “bamboo” Bambusa

arunndinacea (cf. Dendrocalamus

strictus), poykai “pond.” |

|

Ibid. 7 |

Kaṭal “ocean”, poḻil (supra), kamalam (supra) |

|

Ibid. 17 |

Poṉ “gold”, kayal “fish”, puṟavam

“pigeon.” |

Flora and fauna listed above are attestations

of the gorgeous setting of the topography of Kōvalūr.

|

|

|

Figure 1 Map showing [Tiruk]-Kōvalūr |

|

|

|

Figure 2 The landscape graced with the south-Peṇṇāṟu River, Kōvalūr |

|

|

|

Figure 3 View of the Temple with Vijayanagara-Nāyaka period gopuraṃ, Kōvalūr |

|

|

|

Figure 4 Mutal Āḻvārs (bronzes under worship in the temple), Kōvalūr |

|

|

|

Figure 5 Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār (bronze), Ātaṉūr Source https://anudinam.org/2013/11/21/thirumangai-azhwar-avathara-utsavam-at-thirunagari/ |

|

|

|

Figure 6 Trivikrama (calendar art) Source https://kshetrapuranas.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/thiru.jpg?w=584 |

|

|

|

Figure 7 Trivikrama (mūlabera - partial view), Kōvalūr |

|

|

|

Figure 8 View of yagaśālā (see cālai PTM 3.10.8), Āṇṭāḷ Temple, Śrīvilliputtūr: a-b) Ongoing rituals |

|

|

|

Figure 9 Priests reciting the scriptures, Āṇṭāḷ Temple, Śrīvilliputtūr: a) ‘Nālāyiram’-kōṭṭi, b) ‘Veda’-goṣṭi |

|

|

|

Figure 10 “Sea of rice” (see Harle (1958)), Foothills of Koṭaikkāṉal (early 1990) |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I thank the Indian Council of Historical Research for

the project “Nāmāvali of

the Hindu Gods and Goddesses: Reciprocation and Concordance”.

ABBREVIATIONS*

* A few are listed under References

PVP Periyavāccāṉ Piḷḷai

PTM Periya Tirumoḻi

TAN Tiruneṭunṭāṇṭakam

TI Tiruvantāti I

TII Tiruvantāti II

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

Āṟāyirappati Guruparamparaprabhāvam. S. Krishṇasvāmi Aiyaṅkār ed. (Tiruchi: R.S.K. Śrīnivāsaiyaṅkār Family Trust), 1975.

ARE: Annual Reports on Epigraphy. 1900, 1938-39, 1948-49.

Cilappatikāram. Na. Mu. Vēṅkatacāmi Nāṭṭār ed. Chennai: Rāmayya Patippakam, 2011.

Gītā, Bhagavat. Svāmi Citbhavānanda ed. Tirupparāyttuṟai: Śrī Rāmakrishṇa Tapovana, 1977.

IPS: Inscriptions (Texts) of the Pudukkottai State arranged according to Dynasties. Chennai: Government Museum, 2002.

Maṇimēkalai. P.V. Somasundaranar (ed.), Chennai: Kaḻakam, 1975.

Nācciyār Tirumoḻi, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

‘Nālāyiram’: Nālāyirativviyappirapantam. Tamil commentary by Ta, Tiruvēṅkaṭa Irāmāṉucatācaṉ, 4 vols. Chennai: Umā Patippakam, 2010.

Perumāḷ Tirumoḻi, part of Nālāyiram’.

Periya Tirumaṭal, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Periyāḻvār Tirumoḻi, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Peruñcollakarāti II 1989. Tañcāvūr: The Tamil University.

Thurston, Edgar. Castes

and Tribes of Southern India, 8 vols. Government Press: Madras, 1909.

Śrītattvanidhi.

K.S. Sybrahmaṇya Sāstri

ed. 3 vols. [in:] Grantha

with Tamil transl. Tañcāvūr: Tañcāvūr Sarasvatī

Mahal Library, 1964-66.

Tamil Lexicon 7 vols. Madras: University of Madras, 1982

(reprint).

Tēvāram, P.V. Somasundaranar

ed. Chennai: Kaḻakam, 1973.

Tiruccantaviruttam, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tirumālai, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tirumoḻi of Periyāḻvār, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tiruvantāti I, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tiruvantāti II, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tiruvantāti III, part of ‘Nālāyiram.

Tiruvāymoḻi, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

Tiruveḻukūṟṟirukkai, part of ‘Nālāyiram’.

VSN: Viṣṇusahasranāma:

1) T.M.P. Mahadevan ed. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. 1976 [1972].

2) Svāmi Tapasyānanda ed. Mylapore: Śrī Rāmakrishṇa Maṭha, 1986.

Secondary Sources

Alexander,

P. (1965). Shakespeare:

Complete Works. London: The English Language Book Society & Collins.

Brockington, J. (1996). The Sacred Thread. Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press, 222.

Czerniak-Drożdżowicz,

M. (2014). Rituals of the

Tantric Traditions of South India – the text (Canon, Rule) versus the Practice.

Studia Religiologica, 47(4), 253-262.

Dumont, L. (1986). A South Indian Subcaste. Social Organization and

Religion of the Piramalai Kallar. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Gallico, S. (n.d.). Vatican. Rome: Edizioni Musei

Vaticani - Ats Italia Editrice.

Govindasamy,

M. (1979). The Role of

Feudatories in Later Chola History. Annamalai Nagar: Annamalai University.

Hardy, F.

(2014). Viraha Bhakti: The

Early History of Kṛṣṇa Devotion in South India. Delhi:

Motilal Banarsidass.

Harle, J.

(1958). The Early Cōḻa

Temple at Puḷḷamaṅkai (Paśupatikōyil). Oriental

Art, IV, 96-108.

Hudson, D. (1980). Bathing in Kṛṣṇa: A Study

of Vaiṣṇava Hindu Theology. Harvard Theological Review, 73(3-4),

539-66.

Jeyapriya-Rajarajan.

(2008). Aesthetic

Appreciation of Nāyaka Art. In K. C. Reddy, Archaeology and Art New

Dimensions Prof. S.S. Ramachandra Murthy Festschrift New Delhi: Harman. 262-69.

Kalidos, R.

(1983). Trivikrama

Mythology and Iconography. Journal of Tamil Studies, 24, 1-24.

Kalidos, R. (1989). Temple Cars of Medieval Tamiḻaham. Madurai:

Vijay Publications.

Kalidos, R. (1999). The dance of Viṣṇu: the

spectacle of Tamil Āḻvārs. Journal of the Royal Asiatic

Society, 3(9.2), 223-50. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186300011032

Kalidos,

R. (2015). Aṉantapuram:

An Early Base of Viṣṇuism in Kēraḷa. In K. K. Reddy,

Cultural Contour of History and Archaeology in honour of Snehasri Prof. P. Chenna

Reddy (in ten volumes) VII Buddhism and Other Religions New Delhi: Sharada Publishing House.

135-160.

Kalidos,

R. (2015a). Bhatkal or Bhaṭkal?

Some Thoughts for Consideration. In J. Soundararajan, Glimpses of

Vijayanagara-Nāyaka Art New Delhi:

Sharada Publishing House. 135-160.

Kalidos,

R. (2017). Tiruvaḷḷuvar

and Viṣṇuism, Tirukkuṟaḷ vis-à-vis Nālāyiram.

International Conference on Tirukkuṟaḷ Chennai: Institute of Asian

Studies. 126-132.

Kramrisch,

S. (1976). The Hindu

Temple. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Le., B. G. (1974). The World of Indian Civilization.

New York: Tudor Publishing Company.

Liebert, G. (1986). Iconographic Dictionary of the Indian Religions

Hinduism-Buddhism-Jainism. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

Mankodi, K. (1991). The Queen’s Stepwell at Patan. Bombay: Project for

Indian Cultural Studies Project III.

Mookerji, R. (1972). Asoka. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Narayanan,

V. (1995). The Realm of

Play and the Sacred Stage. In W. S. Sax, The Gods at Play: Līlā in

South Asia New York: Oxford University Press. 177-203.

Narayanan,

V. (2007). Tamil Nadu:

Weaving Garlands in Tamil: The Poetry of the Āḻvārs. In E. F.

Bryant, Krishna A Sourcebook New York:

Oxford University Press. 187-206.

O’Flaherty,

W. D. (1994). Hindu Myths.

New Delhi: Penguin.

Parthiban, R.K. & R.K.K. Rajarajan (2016). Nāyaka Chef-d’œuvre. Sculptures of the

Śrīvilliputtūr Tēr. Acta Orientalia, 77, 145-91. https://doi.org/10.5617/ao.5354

Parthiban, R. (2013). Spice Road Vaṭakarai

Zamīndāri: Its Historicity and Architectural Remains. Acta

Orientalia, 74, 91-121. https://doi.org/10.5617/ao.4469

Ragunath,

M. (2014). Nāyaka

Temples: History, Architecture & Iconography. New Delhi: Sharada Publishing

House.

Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2012). Antiquity of the Divyakṣetras in

Pāṇḍināḍu. Acta Orientalia, 73, 59-103. https://doi.org/10.5617/ao.4840

Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2013). Historical Sequence of the Vaiṣṇava

Divyadeśas: Sacred Venues of Viṣṇuism. Acta Orientalia, 74,

3790. https://doi.org/10.5617/ao.4468

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2015). Virāṭ

Rāma and the Monster Kabandha. The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic

Society, 106(1), 7-16.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2015a). Pallava

Vestiges in South Peṇṇāṟu Basin. Annali dell’ Universita

di Napoli “L’Orientale, 75(1-4), 101-118.

Rajarajan, R. (2015b). Early Pāṇḍya Śiṃhavāhinī

and Sapta Mātṛkā Sculptures in the Far South of India.

Religions of South Asia, 9(2), 164-185.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2016). Hail the

Victory of Rāma: Annihilate Terrorism in Laṅkā. The Quarterly

Journal of the Mythic Society, 107(4), 69-89.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2016a).

Masterpieces of Indian Literature and Art: Tears of Kaṇṇaki, Annals

and Iconology of Cilappatikāram. New Delhi: Sharada Publishing House.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2016b). Teppakkuḷam

or Tirukkuḷam of South India: Jalavāstu? Pandanus: Nature in

Literature, Art, Myth and Ritual, 10(2), 83-104.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2016c).

Master-Slave Ambivalence in the hagiography of the Āḻvārs. The

Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, 107(1), 44-60.

Rajarajan,

R.K.K. (2017). Tamiḻ

and Āriyam. Arimā Nokku: International Journal on Language,

Literature, Art, Culture, History, Philosophy and Science, 11(1), 19-23.

Rajarajan, R., Parthiban, R., & Kalidos,

a. R. (2017). Samāpti-Suprabhātam:

Reflections on South Indian Bhakti Tradition in Literature and Art. New Delhi:

Sharada Publishing House.

Rajarajan, R.K.K., Parthiban, R.K., & Kalidos, R.

(2017a). Hymns for Cosmic

Harmony ‘Nālāyirativviyappirapantam’ Four-Thousand Divine Revelations

(Roman Transcription, English Summary and Transcendence). New Delhi: Jawaharlal

Nehru University.

Rajarajan, R.K.K., Parthiban, R.K, & Kalidos, R.

(2017b). Concise

Dictionary of Viṣṇuism Based on

‘Nālāyirativviyappirapantam’. New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Raman, K.

(2006). Temple Art, Icons

and Culture of India and Southeast Asia. New Delhi: Sharada Publishing House.

Santhana-Lakshmi-Parthiban.

(2014). Iconography of the

Śakti Goddesses: A Case for Digitalization. The Quarterly Journal of the

Mythic Society, 106(4), 17-31.

Santhana-Lakshmi-Parthiban. (2015). Trimūrti: Concept and Methodology. The

Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, 106(4), 17-31.

Sastri, K.

N. (1984). The Cōḻas.

Madras: University of Madras.

Seifert, J.

M. (2013). Tending our

Patch of Creation: Engaging Christians in Environmental Stewardship through

Sense of Place. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, 7(3),

265-288.

Stietencron, H. v. (1977). Orthodox Attitudes Towards Temple Service

and Image Worship in India. Central Asiatic Journal, 21(2), 128-38.

Taylor, B.

(2013). Aborphilia and

Sacred Rebellion. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, 7(3),

238-242.

Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2015c). Vañcaikkaḷam Past and Present:

Rāmāyaṇa Panels in a Kēraḷa-Mahādeva Temple.

Acta Orientalia, 76, 127-158.

https://doi.org/10.5617/ao.4454

Wilkins, W.

(2000). Hindu Mythology

Vedic and Puranic. New Delhi: Rupa.

Young, C.

(2000), December 26).

Divyadeśas are Supreme Heavens. The Hindu.

Zvelebil, K. V. (1974). Tamil Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

[1]

I am the Vedas… I am for bhakti

(cf. the Gītā 10.22, 14.14)

Vedānāṃ

Sāmavedo’smi…bhaktaḥ

sa me priyaḥ

[2] Tiruvāymoḻi

(5.6.8 cited in Santhana-Lakshmi-Parthiban (2015), 24)

[3] The Roman transcription and English summary

of the three hymns are presented hereunder (cf. Rajarajan et al. 2007: 43, 89,

133; for a comprehensive dictionary on ‘Nālāyiram’ see Rajarajan et

al. 2017b).

Poykai: Vaiyam takaḷiyā vārkaṭalē

neyyāka/ Veyya katirōṉ viḷakkāka ceyya Cuṭarāḻi

yāṉaṭikkē cūṭṭiṉēñcoṉ

mālai/ Iṭarāḻi nīṅkukavē eṉṟu

“The earth is the lamp-cup! The ghee is the ocean! The scorching sun

is the Light! I have offered the garland of words to the burning-Disc (Lord Viṣṇu)

so that the cycle of bondages (karma

and saṃsāra) are

exterminated.”

Pūtam: Aṉpe takaḷiyā ārvamē

neyyāka/ Iṉpuruku cintaiiṭu tiriyā naṉpuruki/

Ñāṉac cuṭarviḷak kēṟṟiṉēṉ

Nāraṇaṟkku/ Ñāṉat Tamiḻ purinta nāṉ

“With love as lamp-cup; willingness as ghee; affable mind as a wick,

and in deep devotion, I lighted the lamp of omniscient-wisdom of the Lord

Nārāyaṇa. I spin a garland in excelsior-Tamiḻ.”

Pēy: Tirukkaṇṭēṉ poṉmēṉi

kaṇṭēṉ tikaḻum/ Arukkaṇṇiṟamum

kaṇṭēṉ cerukkiḷarum/ Poṉṉāḻikaṇṭēṉ

puricaṅkam kaikkaṇṭēṉ/ Eṉṉāḻivaṇṇaṉ

pāliṉṟu

“I have had a darśana of the auspicious

Śrī-Viṣṇu. I have seen the golden mien. I have enjoyed

the ocean-hue of the Lord. I have seen the brilliance of the Sun’s radiance.

The Lord carries the golden disc ready for war to annihilate the wicked. I have

seen the warped conch in the hand of my Lord today.”

[4] Trivikrama appears as mūlabera of the temples at Kōvalūr,

Kāḻiccīrāma-vinnakaram

(Kāviri delta) and Ūrakam (Kāñci). Vāmana is mūlabera in

Vāṟaṉviḷai/Āramuḻā (Kēraḷa),

called Kuṟaḷappaṉ “Lord Dwarf” (‘Kuṟaḷ’ Nācciyār Tirumoḻi 4.9),

also known as ‘Māṇi’ (literally “penis” Periyāḻvār Tirumoḻi 5.2.5),

‘Vāmaṉ’ (TII 20) and ‘Māṉ’ (Tiruvāymoḻi 4.8.6). For details and illustrations see Kalidos (1983), Jeyapriya-Rajarajan (2008), Rajarajan et al.

(2017) and Mankodi (1991): fig. 71-72).

[5] Veḥkā/Kāñcīpuram (in Perumpāṇāṟṟuppatai),

Śrīraṅgam, Vēṅkaṭam (Tirupati/ Tirumala),

Māliruñcōlai, and Āṭakamāṭam/Aṉantapuram (Kalidos (2015): 312-18) are the earliest

divyadeśas notified in Tamil

literary tradition, e.g., the Paripāṭal

and the Cilappatikāram. The

north Indian divyadeśas codified

in the itihāsas (e.g.,

Ayodhyā, Dvārakā, Śālagrāma,

Devaprayāgaḥ, Badrinātha and so on) are the earliest in the

history of religions, dated in the immortal past.

[6] This hymn has noted ‘Kōval

itaikkāḻi’. Commentators (PVP: Periyavāccāṉ

Piḷḷai c. 1167-1262 CE) suggest the Mutal Aḻvārs met at

Kōvalūr.

[7] Nappiṉṉai is the

Nīḷādevī of the Ācāryas and later Rādha in

Jayadeva’s Gītagovinda (12th

century).

[8] Today is known as

Peṇṇāṟu (noted in Akanāṉūṟu

35, Puṟanāṉūṟu

126; peṇ “woman, bride or wife”

Tamil Lexicon V, 2856), it is the

south Peṇṇai (Figure

2); the

north-Peṇṇai is to the south of the Kṛṣṇā

(Telugu Peṇṇēr).

[9] All hymns end with tirukKōvalūrrataṉuḷ kaṇṭēṉ

nāṉē “I have seen (the Lord) at sacred Kōvalūr” Seifert (2013), Shah (2013): 69-70).

[10] The Vaikhānasāgama

Kalidos (1989): 219) talks of ṣaṭkāla-pūjās at pratyakṣakāla or uṣākāla

(dawn), prabhāta or prātahkāla (early morning), madhyadina (noon), aparāhana (afternoon), sāyaṅkāla

(evening), and niṣī or ardhayāma (night). Kulacēkara

Āḻvār notes the six pūjās

at Śrīraṅgam (Perumāḷ

Tirumoḻi 1.7).

[11] Om śantiḥ śāntih

śāntih; see the Gītā

4.7-8.

[12] Raman (2006): 108-109) notes Tiruvāymoḻi-maṇḍapa,

Vyākhyāna-maṇḍapa,

Gāyatrī-maṇḍapa

and so on (cf. Rajarajan 2006: Annexure I).

[13] Kalaiyamarcelvi or

Mṛgavāhinī, T. Koṟṟavai or

Mahiṣamardinī, Durgā (Cilappatikāram

12.16, 70-71, cf. Rajarajan 2015a: 205-209, fig. IIIa; 2015b: 173-75, Figure

7): Māmakaḷum Nāmakaḷum māmayiṭaṟ

ceṟṟukanta Kōmakaḷum … “Umā, Vācdevī,

and Śrīdevī that slaughtered mahiṣāsura

…” (Cilappatikāram 22, Veṇpā).

[14] Kṛṣṇa tamed the virulent

bulls to take the hand of Nappiṉṉai. Bull-fight was an ancient

martial game of the Tamils (Rajarajan et al. 2017: 205-15).

[15] Tirumaṅkai Āḻvār known

as Kaliyan (enemy of the Kali age) and Maṅkai (literally means “maiden”).

For references see Rajarajan (2016): 82).

[16] PVP spells Kōpālapuram/Gopālapura

that seems to have been a popular name of Kōvalūr during the 12th-13th

century.

[17] Cf. Vintakkaṭikai is “tutelary deity of

the Vindhyas” (Maṇimēkalai

20.120); Vindhyavāsinī-Durgā (Śrītattvanidhi 1.123, Liebert (1986): 339, Santhana-Lakshmi-Parthiban (2014): 76).

[18] Malaiyamāṉs were feudatory of the

region round Kōvalūr, rulers since the Caṅkam Age Sastri (1984): 122, Govindasamy (1979): 168-87, cf. Seifert (2013), Shah (2013) cf. Satyaputra in the Edicts of Aśoka

(see note 32).

[19] Parāṅkuśanāyaki, denotes

the Āḻvār Tirumaṅkai; might as well be a devadāsi or vestal virgin.

[20] Iṭaikkaḻi

here seems to suggest a secret chamber for the Lord (see note 7).

[21] The Āḻvārs in chronological

sequence may tentatively be fixed as follows Hardy (2014): 261-70): Poykai,

Pūtam, Pēy, Tirumaḻicai, Nammāḻvār, Maturakavi,

Toṇṭaraṭippoṭi, Tiruppāṇ, Kulacēkarar,

Periyāḻvār, Āṇṭāḷ, and Tirumaṅkai

(6th-7th to 9th century). For an elaborate

introduction see Rajarajan et al. (2017a): 6-42) and Parthibanand and Rajarajan (2016) (2016: 1-24).

[22] The Ciṟiya Tirumaṭal and

Periya

Tirumaṭal draw a sharp distinction between the

Sanskrit Veda and Tamil Maṟai, scriptures of the

Āryans and Drāviḍians.

[23] The irony in history is that the

‘Nālāyiram’ came to be designated the Drāviḍa-Veda.

[24] The divyadeśas appearing in the cited

hymns are the following: Vēṅkaṭam, Viṇṇakar,

Veḥkā (TI 77); Tañcai, Araṅkam, Taṇkāl, the Ocean

of Milk (Pāṟkaṭal), Mallai, Kuṭantai (TII 70);

Naṟaiyūr (TAN 17), Āli, Nīrmalai (PTM 2.4.1);

Kaṇṇamaṅkai (PTM 7.10.4, TAN 6-7, 17); Kōval or

Kōvalūr appears in all hymns.

[25] “What is the utility of years that do not

listen to the glories of Kṛṣṇa; what is the value of eyes not

viewing the Lord’s dramas, and what is the use of tongues that do not extol the

wonders?” (Cilappatikāram 17,

‘Patarkkaipparval’ 1-3; cf. Rajarajan (2016a): 342). See

‘Tiruvaṅkamālai’ in Tēvāram

(4.9).

[26] Inscriptions in the temple are dated since

the Middle Cōḻa period (Rājarāja I et alii) recording

donations for food offerings (amutu),

abhiṣeka and utsava (for s summary of the

inscriptions see Ragunath (2014): 64-67).

[27] For a compilation of the Viṣṇusahasranāma arranged in alphabetical order

see Rajarajan et al. (2017b): 1652-57).

[28] Pañcāgnitapas

killing the body was not encouraged (Periya

Tirumoḻi 3.2.2, cf. Bon 1974: figs. pp. 54-55).

[29] Pōkattil

vaḻiuvāta (Nācciyār

Tirumoḻi 8.10) Āṇṭāḷ that never departs

from bhoga-mārga.

[30] The Bhāgavata Purāṇa, dated

c. 950 CE O’Flaherty (1994): 17) was not extant during the time of the Āḻvārs

(Hardy 1983).

[31] The Lord’s mistresses are in several thousand

(for citations see Rajarajan et al. (2017b): 1362-63).

[32] Cf. Choḍa Pāḍā

Satiyaputo Ketalaputo (Cōḻa, Pāṇḍya Satyaputra and

Kēraḷaputra) in the Girṇār Edict of Āśoka

Maurya Mookerji (1972): 131-32, 223).

[33] ‘Nāṉmaṟaiyāḷar’ (catur-Vedis),

‘tolcīr-maṟaiyāḷar’ (primeval-Vedis) and

‘arumaṟaiyantaṇar’ (gifted brāhmaṇas)

were a thriving aristocratic population (3,000) in

Tillai-[Cittirakūṭam]. They taught parrots to speak the language of

the Vedas (Periya Tirumoḻi 3.2.2, 6, 8).

[34] The kaḷḷaṉs

till the mid-twentieth century did not follow the Vedic culture in domestic and

temple rituals Dumont (1986) citing Edgar Thurston

1909: see under kaḷḷaṉ).

Today, they are dādās that

could kidnap a brāhmaṇa

priest for his family function (source: contemporary movies).

[35] The Kuṭumiyāmalai Inscription in

the Putukkōṭṭai region (c. 7th century) lists the saptasvaras (IPS, no. 2, pp. 2-7).

[36] The four Vedas

are Ṛg, Yajur, Sāma and Atharva.

[37] The six Vedāṅgas

(again noted in Tiruccantaviruttam

15; PTM 2.5.9, 3.4.1, 5.9.9, 9.1.1) are sikṣa,

chhandas, vyākaraṇa, nirukta,

jyotiṣa and kalpa (Rajarajan et al. (2017b): 1586).

[38] The five sacrifices, pañcamahāyajñas (Tiruccantaviruttam

2) are devayajña, pitṛyajña, bhūtayajña, manusyayajña

and Brahmayajña (Rajarajan 2017b: 25;

see Periyāḻvār Tirumoḻi 4.4.6, Tiruvāymoḻi 7.10.3, PTM

2.5.9, 3.4.1).

[39] The triple fires are garhapatya, āhavanīya

and dakṣināgni Rajarajan et al. (2017b): 870; see TII 96; Tiruveḻukūṟṟirukkai

l. 11; PTM 5.1.8).

[40] R.K. Parthiban working on the

Śrīvilliputtūr was annoyed when we were finalizing the present

article. He was terribly upset because he read the news in the dailies to the

effect that the nitya-amutupati

(daily food offering) to the Nācciyār is stopped because politicians

had swindled the 1,000 acres of lands belonging to the temple Parthiban and Rajarajan (2016).

[41] Indian adjudicators of litigations in High

Courts are much more prudent than temple priests. When the Kāñcīpuram

case was moved in the Court of Law (1970s) the judge judiciously ordered “let

the teṉkalai and vaṭakalai nāmams be affixed to the temple elephant on alternative

weeks”.

[42] Among the twelve, three were brāhmaṇas

Toṇṭaraṭippoṭi, Periyāḻvār, and

Āṇṭāḷ by adoption (notes pārppaṉac-ciṭṭār in Nācciyār Tirumoḻi 6.4);

and almost all the Ācāryas beginning with Nātamuṉi (c.

tenth century Zvelebil (1974): 91).

[43] In the illustrated photo in between the paddy

fields and yonder the hills, a rivulet called Mañcalāṟu (Yellow

River) flows (Parthiban (2013): 93, cf. Map, Plan 3, Figure

9).

[44] A number of medieval inscriptions record

gifts for maintenance of flower garden in temples, e.g., Śrīraṅgam

(vide, 1938-39: 126; 1948-49, no. 3, 109).

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2021. All Rights Reserved.