ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Culture as Commodity: Visual Rhetoric of Tea Advertisement in Colonial India

1 Associate

Professor, Department of English Hansraj College, University of Delhi, New

Delhi, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

examines the popular rhetoric in printed tea advertisements in late

nineteenth and early twentieth-century colonial India. The ethos of

politeness, refinement and urban sociability of England was mapped onto the

Indian culture through advertising campaigns. In the early nineteenth

century, tea brands like Brook Bond and Lipton featured images of white

European women drinking tea promoting it as a luxury item. However, a

decisive shift is noticed in the visual iconography of the early twentieth-century

advertisements where urban elite Indian women replaced white women. The

visual imagery of the Indian ‘subaltern’ women plucking tea leaves with their

nimble fingers in the tea plantation constructed a narrative of feminine care

and oriental delicacy crafted for male fantasy. Thus

the promotional campaigns for Indian-grown British-branded tea have to be

studied within a complex discursive narrative where the woman simultaneously

positioned as both the consumer and the producer of the exotic drink remains

a signifier within the economy of male desire. |

|||

|

Received 03 November 2023 Accepted 21 May 2024 Published 07 June 2024 Corresponding Author Nabanita

Chakraborty, nabanita@hrc.du.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.754 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2024 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Tea Advertisement, Colonial India, Culture, Visual

Rhetoric, Gender, Class, Race |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Advertising in coloured print began with the industrial

and commercial revolution of England in the nineteenth century. The dominant

class of traders and businessmen used their capital resources to procure

technological equipment to produce coloured images in advertising campaigns.

Imperial traders carried raw materials like tea, spices and cotton from India,

processed them in their home industries and then sold these items to elite

British and Indian consumers. The advertisements in daily newspapers and journals

need to be critically examined to underline the success story of British

commercial ventures, the racial hierarchy and the imposition of British culture

on colonised subjects. The paper traces the historical trajectory of British

tea advertisements in colonial India to explore how England's ethos of

politeness, refinement and urban sociability was mapped onto the Indian

culture.[1]

Initially, the tea advertisements featured English men and women as consumers

of tea. However, soon the tea companies

were eager to boost their sales by encouraging tea drinking among Indians. With

the growing tea market in India, the advertisements mostly carried images of

Indian women as consumers of tea. A

populist shift was, however, noticed with the early twentieth-century militant

nationalism when Indian tea companies replaced British brands. The Indian

advertisements promoted the indigeneity of tea with the tagline “100% Swadeshi” and endorsed it as

a national beverage. The objective of this study is to examine how the British

tea advertisements defined culture and shaped commodity fetishism for Indian consumers but the colonial subjects were able to resist

complete cultural subjugation. The

Indian tea companies appropriated tea as an Indian product and defined a

nationalist culture for all Indian subjects during the Swadeshi movement.

Tea as an oriental delight and popular beverage was

introduced to English coffee houses in the eighteenth century. A curtailed

supply of this exotic leaf from China along with its accoutrements of delicate

porcelain Chinaware and a myth of the herbal/medicinal properties of tea

stimulated the sensibilities and defined imperial taste/refinement of British

men/women. An increasing consumer

culture of the quintessential drink forced the Englishmen to look for cheaper options

of tea in their colony India in the nineteenth century. The hilly slopes of

Assam and Darjeeling were transformed into plantation colonies by the East

India Company. The British mercantile instincts motivated new commodity

aesthetics in tea advertisements. Consequently, tea was a marker of social

status, behaviour and culture both in England and the Indian subcontinent.

In England, the tea table became ubiquitous as a space of information exchange; it retained its association with women, luxury, gossip, and domesticity in the cultural imagination. Meanwhile, the East India Company created a market for tea in the Indian colony targeting upper-class consumers especially appealing to feminine sensibilities and tastes. While various tea brands like Brook Bond and Lipton catered first to white European women consumers, the late nineteenth century witnessed a decisive shift in the visual iconography of the advertisements where urban Indian women replaced white women. At the same time, the visual imagery of the Indian ‘subaltern’ women plucking tea leaves with their nimble fingers in the tea plantation constructed a narrative of feminine care and oriental delicacy crafted for male fantasy. Thus the promotional campaigns for Indian-grown British-branded tea have to be studied within a complex discursive narrative where the woman simultaneously positioned as both the consumer and the producer of the exotic drink remained a signifier within the economy of male desire. The shift in the rhetoric from tea production to consumption practices underlined the move from working-class tea plantation women (subaltern others) as desirable objects to urban elite women consumers as desiring subjects. The paper thus aims to trace the commodity aesthetics focusing on issues of race, gender and class dynamics.

2. British

Empire, TEA, and Culture of Consumption

Since the eighteenth century, British culture meant refinement and decorum. Culture could be available to anyone having the economic means to flaunt it. Consumerism was no longer an indulgence but a sign of class mobility promoted by writers like Mandeville (1732) and Smith (1776). Culture, in other words, became a commodity as argued by Brewer (1995). With industrial and commercial growth, a complex network of cash, commodities, people and ideas drove the British Empire. Tea was a lucrative trade for the East India Company and it had a huge impact on the British culture. Coffee houses became a site of cultural exchange over tea and at times on the subject of tea. The setting up of tea plantations in Assam and Darjeeling helped the East India Company to consolidate their imperialist ventures as tea became significant for world trade and the British domestic economy. The Empire had to advertise Indian tea amidst stiff competitors like China and Japan in the world market as observed by Ellis et al. (2015) in an excellent history of British tea. Tea turned from an exotic, expensive product from China to a familiar commodity brought from the British colony and packaged and sold in grocer’s shops, Indian warehouses, coffee houses and pleasure gardens in Britain. Thus tea in the eighteenth century became a popular cultural idiom in Britain. Klein (1994)

3. Rhetoric of

Politeness and Sociability over Tea

Here thou, great Anna! Whom

three realms obey

Dost sometimes counsel take –

and sometimes tea. (The Rape of the

Lock III, 7)

Pope’s mock-heroic poem The Rape of the Lock

compared the act of political counselling with the act of tea table gossip and

sociability. While the coffee houses and clubs became exclusively bourgeois

male spaces where discursive, cultural productions and political deliberations

took place, women were seen presiding over tea tables, playing cards and

indulging in gossip and slanders of the town.

Tea, a foreign luxury and an exotic product coalesced the aesthetic and

the commercial interests of the Englishmen and women. The elaborate ritual

around the tea table became a mark of politeness, sociability and civility, the

idioms that defined the English culture influenced by Shaftesbury’s ‘politics

of politeness’ in his Characteristics. The discourse on tea and its

demand in the market was not simply because of its supposed medicinal and

therapeutic properties advertised by the traders, it also appealed to the

aesthetic sense with its elaborate spectacle and a sense of communion. The ceremony

of tea was a participatory and performative act in which the exotic brew, the

decorative china ware and the fashionable ladies were

all on display. In 1699, Ovington

(1705), a tea expert who

wrote ‘An Essay upon the Nature and Qualities of Tea’ referred to tea as both

civilised and civilising. The British

traders and planters had cleared the jungles, produced machinery, and exploited

cheap labourers (civilising mission) to produce the empire-grown tea (civilised

product) in the hills of Assam and Darjeeling.

Tea, a foreign stranger from the colonies, was packaged, distributed,

marketed and financed by English imperials to satisfy the thirst of global

consumers. In other words, tea, an inanimate object, almost derived an agency,

as it became civilised in its journey from the colony to the empire.

4. Reading advertising Images

A close reading of some of the advertisements informs us about the potential customers and racist bias.

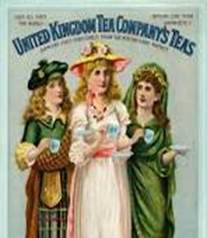

Plate 1

|

Plate 1 United Kingdom Tea Company’s

Teas, The Illustrated London News, 1893 Courtesy HAT Image Gallery (from the

original edition of The Illustrated London News, 1893). https://www.hatads.org.uk/catalogue/record/fe75f010-2396-46c3-a928-a736a51bebe3 |

An advertisement for the United Kingdom Tea Company of 1893 (Plate 1) featured three white women, representatives of England, Scotland and Ireland, drinking tea. The advertisement provided a specific political context about English supremacy where the English lady in white was the dominant figure at the centre while the Irish and Scottish ladies looked towards her for guidance. Tea was promoted as a drink suited for women of polite classes. Another advertisement by the same tea company (Plate 2) focused on the racial ‘other’ as producers and English colonisers as consumers of tea. The advertisement featured an English woman dressed in Roman headgear and a flowing gown leisurely drinking tea while the orientals unloaded and carried cartons of tea in the background. The images of the racial others (Indian and Chinese men) carrying tea in the commercial underscored racial stereotyping as a feature of imperial control of colony India. A white upper-class woman indolently sitting in a luxurious gown and sipping tea was set against the labouring brown men.

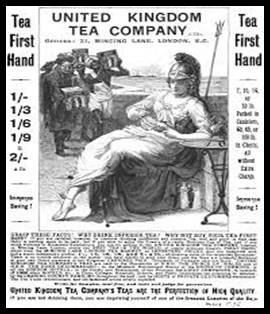

Plate 2

|

Plate 2 United Nations Tea Company, The

Graphic, 15 December, 1894 Courtesy Tea and Coffee 4 (52), John

Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera, Bodleian Library, University of

Oxford, Oxford, UK. |

In Imperial Persuaders, Ramamurthy (2003) observed that the focus on the plantation labourers became one of the dominant representations of Indians. The emphasis on labour was interesting since labour was usually invisibilised. However, the labour shown here was to underline racial hierarchy (93). The advertisement provided other details to its customers: the address of the tea company office, the various packaged quantities available, underlining that thousands of packets were sent out daily to different hotels, restaurants, and railway companies. It specified that the premier tea was used by ‘the royalty, nobility and aristocracy’ with the tagline ‘Why drink inferior tea, why not buy your tea first hand?’ The advertisement thus clearly underlined the race, class and gender bias of the colonisers.

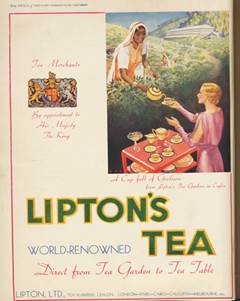

Plate 3

|

Plate 3

Lipton’s Tea, Times of Ceylon, 1935 Courtesy Priya Paul/Tasveer Ghar Collection. |

Other tea companies like Lipton and Brook Bond also

presented the relationship between the colonised producer and the white

consumer. An advertisement of Lipton (Plate 3) had its tagline

“Direct from tea garden to tea table”. The depiction of a dark-skinned

plantation woman labourer serving tea amicably to the English lady legitimised

this racial and class hierarchy.

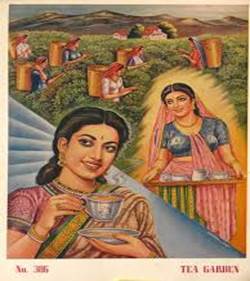

Plate 4

|

Plate 4 Tea Garden No 386,

Empire Calendar Manufacturing Company, Calcutta, 1940s https://scroll.in/article/683453/the-glorious-history-of-indias-passion-for-tea-in-eight-images |

As tea became the Empire’s drink, the East India Company planters and traders shifted their attention to the consumers in India. The legitimating rhetoric of English civility and gendered construals was then transposed onto the Indian middle-class sensibilities. The British Empire pursued a civilising mission in its colony India from the nineteenth century onwards. The British legitimised their rule by claiming to bring moral and material progress to its colony. A culture of sociability and domesticity was imposed on the Indian context as part of the hegemonic practices. The white women in the advertisements were replaced by middle-class Indian women within the household regardless of their differences in race, class and ethnicity. Plate 4 depicts a middle-class Indian woman drinking tea freshly picked and brewed by other Indian women labourers and served by an Indian maid. The visual imagery of the Indian ‘subaltern’ women plucking tea leaves with their nimble fingers in the tea plantation constructed a narrative of feminine grace and reticence to satisfy the sexual fantasy of men. The targeted male viewer had a privileged view of a constructed series of images, visuals so aesthetically beautiful, polished and coherent that the labour at the plantation was hidden from view.[2] The image of the beautiful mountains, the lush green plantation and the adorned beautiful women looked picturesque, emblematic of oriental delight. The bodies of the labouring women were created by cultural fetishism of both labour practices and cultures of consumption Chatterjee (2001).

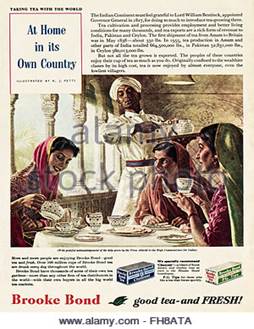

Plate 5

|

Plate 5 Brooke Bond Advertisement,

1956. Courtesy F8 archive Alamy

Stock Photo, 1956 |

A Brooke Bond advertisement (Plate 5) in a poster assimilated coloured images, tagline and public information to form a complete narrative. The tagline promoted ‘at home in its own country’ which valourised Lord Bentick as the Governor General for providing employment opportunities and better living conditions to Indian natives. The image upheld the moral virtue of good culture, sociability and polite conversation. The setting was in some old haveli or aristocratic mansion where the three women seemed at leisure. The male butler occupied a fourth subject position with a dominant gaze on the beautiful women who carried on a conversation over tea. His presence set a discordant note to female intimacy and conviviality. The butler occupied a liminal space due to his low-class position and outsider status. However, he was at a vantage point to gaze silently at the female subjects who were seen as commodified objects of pleasure. Over the years, such marketing strategies seemed out of sync with the values of Indian consumers. Some companies believed that the prestige of foreign brands was sufficient to attract middle-class English-speaking Indian buyers. The need for customised approaches to Indian consumers based on their real demands never arose till the early twentieth century.

5. Indigenous

Tea and Swadeshi Movement

The alienation of the imperialist planters from the native Indians and the hostility of local elites meant that the English planters were dependent on middlemen for the fiscal and political navigation of an unknown land Chatterjee (2001), 97. This gave the local indigenous elite Bengalis and Marwaris to invest in their plantation economy. Between 1879 and 1910, Jalpaiguri-based entrepreneurs invested in eleven tea companies. The Indian tea companies changed the visual imagery and the discourse of the advertisements. Tea was no longer a luxury product for the elites but a commodity of mass appeal. In a Hindi advertisement in a national daily, tea drinking was promoted as “Anivarya Nitya karma” (an essential daily ritual). The advertisement in Hindi was meant for non-English speaking native men and women. The Tea Board of India (reorganised in 1953 to replace The Indian Tea Market Expansion Board) declared the imperial drink as emphatically Swadeshi.

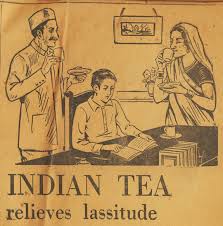

Plate 6

|

Plate 6 Indian Tea Relieves

Lassitude, 1940 Courtesy Priya Paul Collection, New

Delhi. https://heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/detail/649411 |

Plate 6 shows a tea promotion

where Indian tea could relieve lassitude and invigorate people to work for the

freedom movement. The focus on women drinkers in the visual images of earlier

advertisements had a negative effect whereby tea was considered a lady’s drink

‘unfit for man’. Tea was now promoted as

a family drink and a popular beverage with health benefits. Tea was not

restricted to a man or a woman but catered to the needs of all family members.

The upright position of the man and the woman in the image underlined the

everyday ritual of tea drinking without a ceremonial display of porcelain

crockery or delicate expensive chinaware.

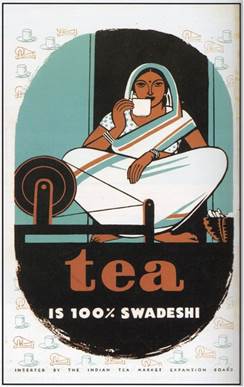

The visual image in Plate 7 was firmly located within the Swadeshi movement in the twentieth century, the period of Indian freedom struggle which countered British goods with indigenous products. The clarion call for Swadeshi goods lauded indigenised tea grown by native planters. Annada Munshi, a commercial art designer, incorporated the emblem of the spinning wheel and appropriated tea within Gandhian ideals. The visual representation of the woman at the spinning wheel, a symbol of the village cottage industry led by Mahatma Gandhi, promoted Swadeshi fabric with Swadeshi tea. Indian colony countered not simply Western goods and their visual representations but also shunned British ideology and rhetoric. A similar advertisement ‘Gupta’s Teas’ came in a Bengal daily with the caption “Support your own country. Gupta’s teas are made from the Indian plant of Indian labour and capital”. The image showed Indians of different religious and regional backgrounds trying to support a large map of India. Indian tea companies therefore made an epistemic shift from the British rhetoric and images of tea promotion to transform tea “from an imperial product to a national drink” Bhadra (2005).

Plate 7

|

Plate 7 Tea is 100% Swadeshi, 1947 Courtesy Urban History Documentation

Archive, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. From Lutgendorf,

Philip. "Making Tea in India: Chai, Capitalism, Culture." Thesis

Eleven 113, no. 1: 19. |

6. Conclusion

The visual rhetoric of tea in colonial India underlined the mission of the empire to refine and civilise both the Indian raw tea and its consumers. The attempt was to redefine moral and material culture for the Indian buyers by instructing them how to make, serve and consume tea. Shaftesbury (1999) rhetoric of sociability, politeness and decorum was imposed onto the Indian culture without accounting for its unique particularity. The civilising mission subsumed the rhetoric of the moral, material, and cultural progress of the natives. The paper has pointed out the tensions, gaps and paradoxes in the civilising mission carried out by the British Raj. In the wake of the freedom struggle movement, an epistemic shift was visible in the visual imagery of the advertisements where the Indians internalised elements of the colonial civilising mission to carry out self-civilising enterprises. Tea drinking became a regular daily routine for people across age, class, and gender barriers. The Swadeshi movement initiated the promotion of Indian tea grown on Indian soil and the nationalist popular rhetoric replaced the Western concepts of consumer culture. The paper has traced a historical trajectory of tea advertisement in colonial India. It has explored how the British tried to define ‘culture’ and encourage commodity fetishism in the colonised subjects. However, the Indians resisted such cultural subjugation at the hands of the British Raj. The Indian tea companies appropriated tea as a nationalist drink, completely indigenous and local. The visual rhetoric of the promotional campaigns changed from upper-class female social gatherings at the tea table to an everyday ritual in the Indian household. The use value of tea “to relieve lassitude” and reinvigorate health synchronised with the clarion call for militant action against colonial rule.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bhadra, G. (2005). From an Imperial Product to a National Drink: The Culture of Tea Consumption in Modern India. Tea Board India.

Brewer, J. (1995). “The Most Polite Age and the Most Vicious”: Attitudes Towards Culture as a Commodity, 1660-1800’, The Consumption of Culture 1600 – 1800: Image, Object, Text, eds. Bermingham, Ann and J. Brewer, London: Routledge.

Chatterjee, P. (2001). A Time for Tea: Women, Labour and Post/Colonial Politics on an Indian Plantation, Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11cw1bt

Ellis, M., Coulton, R., & Mauger, M. (2015). Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World. Reaktion Books.

Klein, L. E. (1994). Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourse and Cultural Politics in Early 18th C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mandeville, B. (1732). The Fable of the Bees or Private Vices Public Benefits. Verlag Wirtschaft u. Finanzen.

Ovington, J. (1705). An Essay upon the Nature and Qualities of Tea. John Chantry.

Ramamurthy, A. (2003). Imperial Persuaders: Images of Africa and Asia in British Advertising. Manchester University Press.

Shaftesbury, (1999). Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times. Ed. Lawrence E. Klein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sharma, J. (2011). Empire’s Garden: Assam and the Making of India. Durham: Duke University Press.

Smith, A. (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Ghent University: W.Strahand and T. Cadell.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.