ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Weighted Matrix Index: A Tool to Decode the Interconnectedness of Socio-Cultural Expressions, Urban Context and Built Environment

Shanu Raina 1![]()

![]() ,

Bhagyalaxmi Subhas Madapur 2

,

Bhagyalaxmi Subhas Madapur 2![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, BMS School of Architecture, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2 Co-Founder,

369 Ochre Studio, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

ever-changing nature of our urban fabric reflects the complex cultural and

socio – economic environment we live in. Globalization has brought with it a

shift in the way we view our cities, from traditional urban forms that

consider the wisdom and skills of our ancestors to analytical diagrams

largely used to facilitate urban development. While this has resulted in a more

efficient and convenient urban environment, it has also led to an insensitive

and unresponsive urban fabric. Fortunately, there are examples of urban forms

that have managed to preserve their significance over a long period of time,

while still being adapted to the changing cultural and socio – economic

contexts. These examples prove that it is possible to create places that are

both timeless and responsive to the needs of the present and serve as

inspirations for cities of the future. The purpose of this research study is

to examine the role of design in shaping the continuity and change of urban

fabric. Specifically, this paper investigates the relationship between

contextual factors and design decisions that contribute to the evolution of

the built environment in urban areas set in unique contexts. Within this

framework, this paper aims to intricately compare and contrast Rome and

Bhutan as distinctive urban environments, each situated within its own unique

settings. This research study has used an approach that combines analysis of

development processes, observation notes, documentary reports, published

literature, and studies of case examples to investigate the relationship

between design decisions and the continual change in the urban fabric. This factor,

in particular underpins the relationship between the built environment and

socio-cultural expressions that inform contextually appropriate design. A

tool (weighted index matrix) for deciphering the interconnectedness between

socio-cultural expressions, urban settings, and built environments was

developed as a result of the research study. Further, the matrix index has

been applied for the two select case examples and the results have been

evaluated and analyzed. |

|||

|

Received 29 August 2023 Accepted 09 December 2023 Published 14 December 2023 Corresponding Author Bhagyalaxmi

Subhas Madapur, bhagya.chandgude@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2

ECVPAMIAP.2023.702 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Urban Context, Built Environment, Socio-Cultural

Expressions, Continuity, Weighted Matrix Index |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Human settlements embody the cultures that constructed them, shaped across generations by an evolving comprehension of environmental dynamics and societal needs. Yet, the built forms of these places can often outlive the society that created them, and globalisation has led to a shift in the way cities look and feel Eldemery (2009). The complex and multidimensional effects of advanced capitalism and neo-liberal policies on urban form are still a topic of discussion among academics and decision-makers. While some contend that these policies have aided in the widening of social and economic inequalities in the built environment, others contend that they have facilitated urban growth and development. The livability, equity, and sustainability of cities have reportedly suffered as a result of these tendencies, according to evidence.

However, cities are remarkably resilient and have the ability to evolve and adapt over time in order to be timeless and relevant. There are numerous examples of urban forms that have adopted innovative and sustainable urban development techniques to maintain their significance while also transforming the constantly changing needs of their inhabitants Glaeser (2011).

For instance, cities like Paris, London, and Barcelona have been able to keep their traditional urban form and architectural style while simultaneously adjusting to contemporary needs. While new infrastructure and transportation systems have been developed in these cities to meet evolving means of transit and mobility, historic structures and neighbourhoods have been maintained and rehabilitated. There are other cities that have embraced social and economic inclusion, like Seoul, Barcelona, and Berlin. To address issues of inequality and social exclusion, these cities have implemented policies and programmes that assist small enterprises to enhance the quality of life while also providing affordable housing and community development projects. These examples demonstrate that it is feasible to design locations that pay respect to the past while also being a part of the present and can act as models for other cities.

Settlement patterns are the visible manifestations of a community's social and cultural ideals. A location's settlement pattern is shaped by the distinctive amalgamation of numerous urban components, including its streets, public spaces, green spaces, and built forms. The positioning and style of buildings can have a big impact on a place's character and significance. Therefore, while introducing new buildings, it is crucial to take the present style of architecture and the local setting into account. Early 20th-century modernist architecture frequently places an emphasis on originality, which can result in structures that don't fit in with their surroundings. The need to respect and enhance the local architecture could often be in conflict with this.

Nevertheless, it is possible to conceptualise innovative designs while simultaneously rendering respect to the existing built environment, historical relevance, and existing urban fabric. This strategy necessitates sensitivity to and comprehension of the situation and community needs. To preserve a location's cohesiveness and distinctive identity while also fostering growth and innovation, careful consideration of how new built form development may affect the existing urban fabric is crucial.

1.1. Socio-Cultural expressions, Urban Contexts and Built Environments

The relationship between socio-cultural expressions, urban context, and built environment is complex and dynamic, involving several variables and interactions. It refers to the extent to which closely related and interdependent a city's or urban area's physical, social, and cultural components are. It recognises that an urban area is more than just a physical location; it is also a space for culture and social interaction between people and the built environment.

The diverse means by which individuals display their culture and social identities, including language, art, music, religion, customs, and traditions, are referred to as socio-cultural expressions. The urban setting and built environment, which include components like geography, history, politics, economy, and technology, form these expressions, which have a strong social and cultural underpinning. A thriving street art scene, for instance, can transform a deteriorating neighbourhood into a cultural centre, and traditional religious beliefs can affect the design of religious structures and public spaces Naghizadeh (2000).

The urban context refers to the physical, social, and economic characteristics of urban areas, including their size, population, infrastructure, and built environment. Urban contexts can shape socio-cultural expressions by providing spaces and opportunities for artistic and cultural activities, as well as by influencing the social and economic factors that support or hinder these expressions Granham & Thomas (2007).

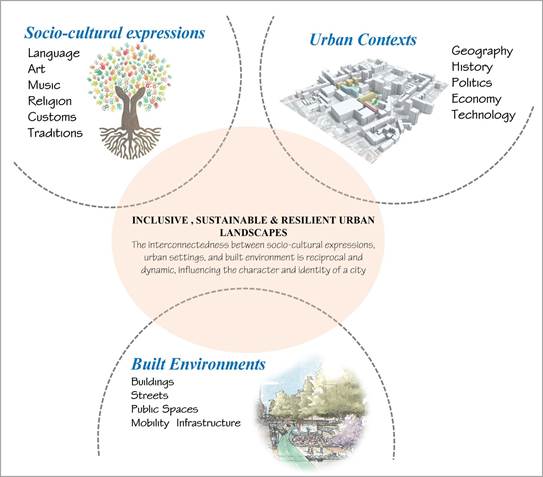

Buildings, streets, public spaces, and mobility infrastructure collectively comprise the built environment, which is crucial in determining both socio-cultural expressions and urban environments. Cultural expressions and activities, as well as the social and economic forces that sustain them, are impacted either positively or negatively by the way these places are designed and used. An opportunity for social contact and cultural expression, for instance, can be provided by the design of public areas like parks, plazas, and cultural institutions. Additionally, the urban environment can have an impact on the kinds of socio-cultural expressions that develop and flourish in a certain location. For example, while a homogenous or segregated urban context may limit the range and quality of cultural expressions, a diverse and inclusive urban context may encourage the emergence of new cultural expressions and creative practices (Refer Figure 1).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Significant Features

of the Inclusive, Sustainable and Resilient Urban Landscapes Source Authors |

In

this sense, the link between socio-cultural expressions, urban setting, and

built environment is reciprocal and dynamic, influencing the character and

identity of a city. Building inclusive, sustainable and resilient urban

landscapes that enable a variety of socio-cultural expressions and encourage

community involvement requires an understanding of these linkages and how they

are interconnected.

2. Materials and Methodology

This research study is primarily

focused on deciphering the interconnectedness of socio-cultural expressions,

urban context and built environment. The

research study explores the interrelation between contextual variables and

design decisions that contribute to the evolution of the built environment in

urban areas set in unique contexts. The theoretical framework of contextual

settings and socio-economic expressions and the application framework of

planning and design process have been used as underpinning premises for

positioning the research study and the analysis. The research analysis

is illustrated through the use of two case examples, each within its unique

context. Further, a tool for recognising the interconnectedness

between socio-cultural expressions, urban settings and built environments was

developed as a result of the research study. The following methodology

framework was established to conduct the research study (Refer Table 1).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Details of the Methodology Framework |

|

|

S. No. |

Methodology Framework |

|

1 |

Introduction |

|

2 |

Materials

and Methodology ·

Research Statement ·

Research Questions ·

Research Aim ·

Research Objectives ·

Research Methodology |

|

3 |

·

Socio-Cultural Expressions: Needs, Continuity and

Spatial Characteristics ·

Architecture of the Built Environment - An

Expression of the Socio-culture Fabric and Urban Context ·

Case Example 1: Rome – An Imperial City ·

Case Example 2: Bhutan- A Buddhist Kingdom Historicity Reconnoitering the

Interplay between History and Context Exploring the

Characteristics of Place Synthesizing Context and

Architecture: A Unified Approach |

|

4 |

·

Comparative analysis of the case examples to co-relate the region's

historical and contemporary development developed over a period of time ·

Formulation of a tool (weighted index matrix) for recognizing the

connections between built forms, urban surroundings, and sociocultural

expressions ·

Analysis and Results |

|

5 |

Conclusion |

|

Source Authors |

|

2.1. Research Statement

The research design of this study is

based on a qualitative approach that emphasizes the exploration of complex

phenomena in natural settings. The study employs case studies to investigate

the specific design decisions that have been made in different urban contexts

like Rome and Bhutan and their impact on the continuity and change of the built

environment. The cases selected for this study are representative of different

urban contexts and design approaches, including historic preservation, urban

renewal, and contemporary development. Case studies involve an in-depth

examination of specific design projects, including analysis of design documents

and site visits, of both Rome and Bhutan.

The data collected through case using

thematic analysis. This approach involves identifying patterns and themes such

as a) Historicity, b) Exploring the interplay between history and context, c)

Exploring the characteristics of place and d) Reconciling the realms of context

and architecture that emerge from the data and developing a comprehensive

understanding of the factors that contribute to the continuity and change of

urban fabric.

2.1.1. Research Questions

1) What

are the vital factors that strongly impact the interconnectedness of built

forms, urban context, and socio-cultural expressions?

2) How

do the cities of Rome and Bhutan compare in terms of Built Form, Urban Context,

and Socio-Cultural Expressions?

3) How

does the urban context differ between the two case examples?

4) Which

case example has a strong socio-cultural expression?

5) Which

case example has a comprehensive built environment?

2.1.2. Aim

The research study examines and

compares the interconnectedness of the socio-cultural expressions, urban

contexts, and the built environment of the selected case examples by applying

the formulated weighted index matrix approach.

2.1.3. Research Objectives

·

To signify the connectedness and

correlation between inhabitants, built forms, urban context, and socio-cultural

expressions.

·

To explore the relevance and influence

of unique contextual settings on the built environment.

·

To explore the crucial development

elements and their impact on the fabrication of the built environment which is

essential in creating a sense of place.

·

To formulate a tool (weighted index

matrix) for recognizing the connections between built forms, urban

surroundings, and sociocultural expressions.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Data Collection

To collect data, information on the

categories and subcategories listed in the weighted index matrix were gathered

from a variety of sources. This entailed conducting a detailed analysis of

existing literature, scholarly articles, research papers, and studies that

scrutinize the urban planning and design facets of Rome and Bhutan. In order to

collect pertinent information, official websites and internet resources like

the Open Data Catalogue of the World Bank and the Human Development Index of

the United Nations Development Programme were also consulted.

2.2.2. Weighted Index Scoring

After the data was gathered, each

category and subcategory received a weighted index score. According to the

percentages supplied in the matrix, weights were assigned to each category and

subcategory. To get a weighted score, the weightages given to each category and

subcategory were multiplied by the scores for each case example. The weighted

index score for each case example was calculated by adding all of the weighted

scores for that particular case example.

2.2.3. Comparative Analysis

The methodology's final step compared

the weighted index scores of Bhutan with Rome. In terms of socio-cultural

expressions, urban context and built environment. The scores were compared to

highlight the similarities and contrasts between the two select case examples.

Descriptive statistics, statistical analysis, and graphical representation are

only a few of the approaches that were used in the investigation.

2.2.4. Final Interpretation

The answers to the research study

questions were used to interpret the findings. In doing so, conclusions about

Rome's and Bhutan's urban planning and design features, as well as the elements

that contribute to each place's distinctive character, were reached.

3. Socio-Cultural Expressions: Needs, Continuity and Spatial Characteristics

There is certainly much more to a city

than its visible structures. It is a living thing that changes and evolves with

time. A city's distinctive characteristics are influenced by its inhabitants,

the cultures they develop, and the activities that take place there. Culture is

embodied in various forms such as folklore, beliefs, lifestyles, rituals, built

environments, and public spaces which in turn shape the landscapes of different

societies. The way-built forms appear and function is primarily shaped by socio-cultural

demands. To achieve a better design approach, one needs to respond to the

context, which is commonly referred to as the 'setting', with a sensitive

understanding. The interplay between the built environment and its

context—spanning historical, political, socio-cultural, economic, and physical

aspects—shapes the distinct identity of a place. There are three types of

contextual references: visual context, formal context, and human context.

Visual context refers to the visual appropriateness of the built environment,

while formal context is concerned with scientific environmental data. Human

context, on the other hand, deals with cultural values and identity. Architecture

stands the test of time when it harmoniously responds to both socio-cultural

and physical environments Radstrom (2011).

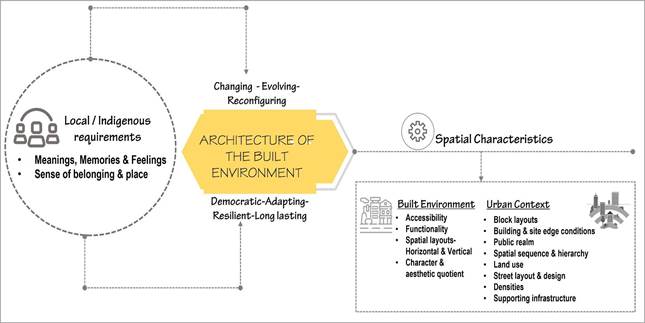

3.1. Architecture of the Built Environment - AN Expression of Socio-culture Fabric and Urban Context

Architecture, as a cultural expression,

shapes cities beyond buildings; it profoundly influences the continual renewal

of the cities. Inhabitants' lifestyles shape building designs, dictating

spatial use, layouts, and sizes. Enduring principles linked to land, climate,

symbols, and organization persist across cultures, guiding the remarkable

architecture of the settlement to encapsulate the essence of a place within

urban landscapes, despite external changes. (Refer Figure 2).

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Architecture of the Built Environment - An Expression of Socio-Culture Fabric and Urban Context Source Authors |

The rich and varied experiences of the

inhabitants representing heterogeneity of socio-cultural dimensions of a city

are reflected in the diversity of the city, as are the different ways in which

they engage with the urban contexts and the built environment. Leveraging a

wide range of perspectives, knowledge, skillsets and resources, diversity

enables cities to continuously change and adapt to challenges and new

possibilities. This diversity is the primary component that makes urban areas

dynamic, sustainable and resilient. Cities must embrace and celebrate this

diversity in order to thrive in these dynamic circumstances. They must endeavor to build inclusive and equitable communities that

meet the needs and ambitions of all of their inhabitants Rossi (1982).

3.2. Case Example 1: Rome – An Imperial City

3.2.1. Historicity

Cities can provide a unique sense of

belongingness and identity, even if they appear ordinary. Designed and

constructed over time, cities are spatial constructs. They are complex,

intricate systems that require prolonged experience to properly comprehend. The

imperial city of Rome serves as a notable illustration of this concept. Rome

has had an immense impact on global architecture and urban planning, with a

history spanning over twenty-eight centuries. The city's architecture comprises

numerous layers, each reflecting the societal, economic, cultural, and

political conditions of the time Parvizi (2009).

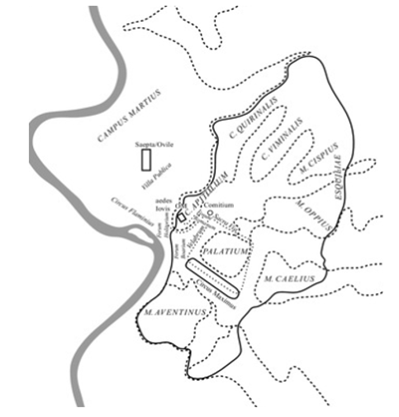

3.2.2. Reconnoitring the Interplay

between History and Context

Situated at the heart of the Italian peninsula, Rome was founded in 753 BC, located along the Tiber River. Legend has it that the city was constructed by twin brothers, born to a princess who was impregnated by Mars, and saved from drowning as infants by divine intervention. The brothers were raised by a she-wolf, revered as a sacred animal by their father Niebuhr (1851). Rome emerged as a cultural and political center, with adept engineers known for pioneering water systems and road networks, and much like the Greek Agora, Roman forums thrived as the vibrant hubs of civic life. After Julius Caesar's unification, Rome became a republic, elevating rulers to divine status and emphasizing imperial grandeur over religion. This shift prioritized the empire over religion, fueling a surge in monumental architecture across the Roman Empire facilitated by the innovation of lime concrete. The resulting structures—amphitheaters, aqueducts, theaters, basilicas, and temples—stand as an enduring testament to the grandeur of the era.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 The Geographical

Setting of Rome Source Ziolkowski (2013) |

3.2.3. Exploring

the Characteristics of Place

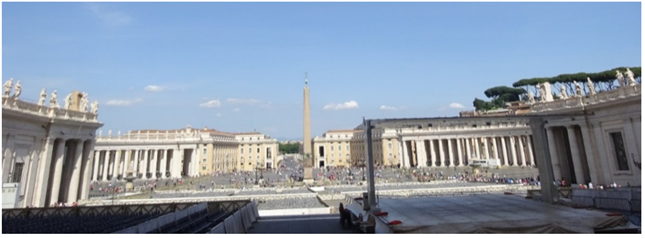

The Romans constructed buildings with a grand and imposing quality, evident in their use of materials such as limestone, concrete, and mortar. Notable examples of this monumental characteristic can be seen in structures like the Colosseum's canvas roof (Velarium), Trajan's Column, the Temple of Saturn, and many more. Roman architecture employed several key building systems, including lintelled structures inspired by the Greeks, vaulted structures influenced by the Etruscans, and striking arcading, barrel vaults, domes, thick walls, decorative columns, fountains, sculptures, piazzas, squares, and the use of stone to adorn buildings. The images below depict some of the defining features of Roman architecture.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 St. Peter’s Square, Vatican City |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Colosseum, Rome |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Pantheon, Rome |

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Bridges Rome |

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Trevi Fountain, Rome |

3.2.4. Synthesizing Context and Architecture: A Unified Approach

Rome's classical architecture

profoundly influenced modern architectural design language. The city boasts a

rich historical context that has evolved over centuries, with each part

contributing to the whole and vice versa. Aesthetic coherence is crucial, and

every element in a place must work together to create a sense of place. For

instance, the streets of Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood

are aesthetically unified, which adds to their beauty. In contrast, the Tour

Montparnasse in Paris draws attention to itself and is not in harmony with its

surroundings. Capitalism can have a negative impact on culture, resulting in

the creation of ugly places Robinson (2017).

Despite Rome's rich architectural

heritage, many contemporary buildings in the city lack the design language of

classical architecture and fail to respond to their context. Instead, these

buildings prioritize their own self-expression over fitting in with their

surroundings. Examples of such buildings include Richard Meier's Ara Pacis

Museum, Zaha Hadid's MAXXI, Renzo Piano's Auditorium Parco della

Musica, and Massimiliano Fuksas's Rome Convention Centre.

Architecture and place are inherently

intertwined. The factors that shape a building are important, but the

connection to its immediate environment and thus its ability to fit in is

equally important. For a building to be successful, it must be sensitive to its

context and form a meaningful connection with its surroundings.

3.3. Case Example 2: Bhutan - A Buddhist Kingdom

3.3.1. Historicity

Situated on the eastern edge of the Himalayas, Bhutan is a

relatively small Buddhist kingdom. Despite this, traditional life and

culture are still very prominent in Bhutan, with many of its citizens living a

self-sufficient lifestyle and relying heavily on agriculture and cottage

industries such as weaving and handicrafts. Additionally, Bhutan has been

welcoming eco-tourism with its 'High Value Low Impact' policy, which has been

helping to drive economic growth without harming the environment or culture. This

policy aligns with Bhutan's Gross National Happiness (GNH), prioritizing the

environment and culture over unchecked economic growth.

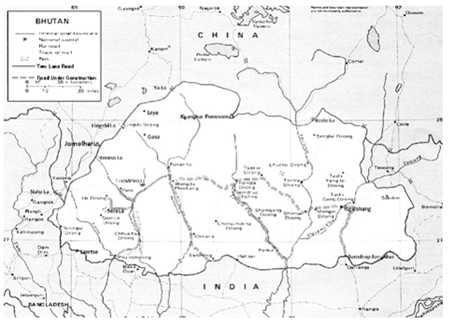

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Settlement Map of Bhutan |

3.3.2. Reconnoitring the Interplay between History and Context

Buddhism deeply influences Bhutan's

spiritual heritage. Bhutanese architecture embodies its socio-cultural essence,

seen in its monuments, monasteries, and religious sites. The country spans

diverse climates, from alpine regions in the Himalayas up north to sultry

tropics in the south.

In its modern development phase, Bhutan

is working towards preserving its traditional architecture's cultural relevance

and sustainability. Government policies like Structure Plans, Local Area Plans,

and Development Control Regulations aim to mitigate urbanization's negative

impacts on the environment, culture, and architectural heritage.

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Bhutanese Settlements: Harmonizing Traditional Architecture with Contemporary Built Forms and Physical Context Source Authors |

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Bhutanese Settlements: Harmonizing Traditional Architecture with Contemporary Built Forms and Physical Context Source Authors |

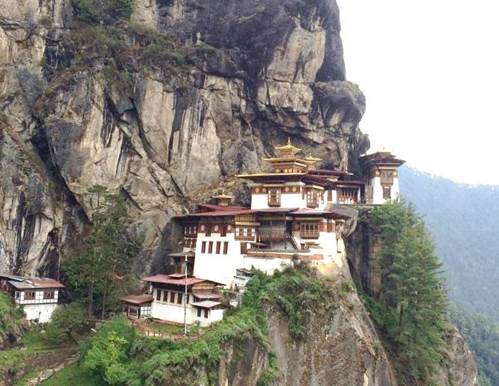

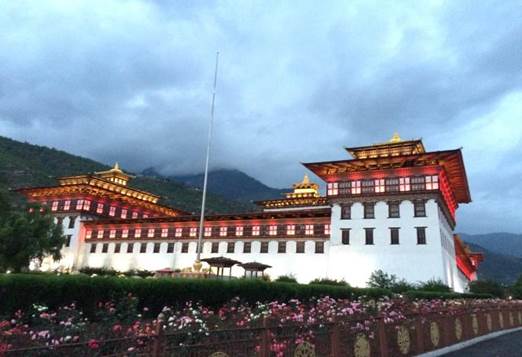

3.3.3. Exploring the Characteristics of Place

Bhutanese architecture, deeply rooted

in culture, holds a distinctive identity. It embodies traditional values while

interpreting various cultural aspects. Craftsmanship, seen in these impressive

structures, emphasizes shared values over individual expression. These timeless

monuments blend spiritual symbolism with organic and geometric shapes, standing

as enduring testaments to both aesthetic appeal, functionality, and

sustainability.

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Taktsang Monastery: Embracing Nature in Architecture (left) and Tashichho Dzong: Traditional Essence portrayed (right) Source Authors |

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Taktsang Monastery:

Embracing Nature in Architecture (left) and Tashichho

Dzong: Traditional Essence portrayed (right) Source Authors |

The notable structures prioritize

practical function and aesthetics. While sharing design elements, every region

has unique distinct architectural styles, utilizing local techniques, materials,

and craftsmanship to cultivate visual richness, quality, and a sense of human

scale. Bhutanese architecture, emphasizing sustainability and harmony with

nature, reflects the nation's unique traditions and culture.

3.3.4. Synthesizing Context and Architecture: A Unified Approach

Bhutan's enduring traditional

architecture signifies the nation's resilience despite limited military or

economic strength. Amid global cultural shifts, Bhutan stands out for its

commitment to preserving its distinct identity. Its architectural expressions

remain vital in safeguarding this identity, showcasing how culture and climate

influence structural design. Bhutan recognizes the power of its native

architecture, utilizing it for both economic and aesthetic advantages.

4. Comparative analysis of the case examples

Contemporary designs in revered

settings should acknowledge and adapt to the city's enduring context, pivotal

in its evolution. Analyzing both built structures and

their surrounding systems is vital. Historical elements enrich the visual

backdrop, influencing successful modern designs and forging new relationships

between architecture and its surroundings. Striking a balance between honoring tradition and pursuing innovative approaches is

key.

4.1. Context - A Constraint or a Design Tool

Context should not be viewed primarily

as a constraint, but rather as a tool that can help generate apt design

solutions. Contextual data has an enormous influence on the built form and is

essential in creating a sense of place. Contemporary times demand a

re-conceptualization of context, and limitations should be viewed as an

opportunity. Designing within a context demands more than mere conformity; it

entails surpassing rigid form and style. Each context, unique in its values,

demands a holistic analysis for the most appropriate solutions. Understanding

the interplay between context and architecture involves considering various

elements—built form, development patterns, vistas, scale, construction methods,

and materials. The interplay between context and architecture is mutually

influential, demanding a comprehensive analysis that correlates.

Tool for recognizing the

interconnectedness of sociocultural expressions, urban contexts and built environment.

Planners and designers may build urban environments that are not only practical

but also meaningful and representative of the distinct identity of the

community by taking the context, urban form, and socio-cultural manifestations

of a city into consideration (Refer Table 2).

Table 2

|

Table 2 Tool for Comparative Analysis of Bhutan and Rome Based on Context, Urban Form, and Socio-Cultural Expression Factors |

||||

|

S. No |

Category |

Factors to Consider |

Bhutan |

Rome |

|

1 |

Context Analysis |

Historical

and Cultural Heritage Context Masoud & Guan (2015) |

Ancient Roman history |

Buddhist history and culture |

|

|

|

Geographical Context |

located on banks of the Tiber

river |

Landlocked Himalayan Kingdom |

|

|

|

Political

Context |

Capital

City of Italy |

Constitutional

Monarchy |

|

|

|

Economic Context |

Developed economy with tourism and fashion

industries |

Developing economy with agriculture and tourism

industries |

|

2 |

Urban Form Analysis |

Spatial

Layout /streets network Jacobs (1961) |

grid

- iron systems with major road leading to historic landmarks |

Organic

street layout with winding roads and alleys |

|

|

|

open spaces Lynch (1960) |

Piazzas and public squares |

Public plazas and Chortens |

|

|

|

Typology

of Buildings Cuthbert (2006) |

Monumental

Public buildings, palaces and churches |

Traditional

Bhutanese architecture architecture with dzongs and

chortens |

|

|

|

Land use |

Mix residential, commercial and government buildings |

Dominated by religious and government buildings |

|

3 |

Socio - Cultural Expression Analysis |

Cultural

Traditional Practices/Religion Masoud & Guan (2015) |

Paganism

and Christianity in past, secular today |

Mahayana

Buddhism and Bon Tradition |

|

|

|

Language |

Latin in past, Italian today |

Dzongkha and numerous regional dialects |

|

|

|

Art

and Aesthetics |

Classical

Roman Art and architecture, Renaissance art and sculpture |

Buddhist

iconography and traditional arts and crafts |

|

|

|

Social Customs |

Emphasis on family, community, and social

hierarchy |

Emphasis on harmony, respect and spiritual;

values |

|

Source Authors |

||||

4.2. Formulation of a Tool: Weighted Matrix Index

A method to recognise the

interconnectedness between socio-cultural expressions, urban context and built

environment is provided by this tabular checklist. Planners and designers may

build urban settings that are not only functional but also meaningful and

representative of the distinct identity of the community by taking into account

the socio-cultural expressions, urban context and the built environment. The

ultimate objective is to develop livable, sustainable

urban environments that honour and celebrate the various cultural customs and

traditions of the neighbourhood (Refer Table 3).

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparison of Socio-Cultural Expressions between Rome and Bhutan |

||||

|

Parameters |

Indicators |

Score based on |

Bhutan (SCORE) |

Rome (SCORE) |

|

Built

Form (30%) |

Building

types (5%) |

Variety

and Adaptability of building types for different users |

3 |

4 |

|

Architectural style

(10%) |

Diversity and Quality

of architectural styles |

4 |

5 |

|

|

Urban

morphology (10%) |

Legibility,

Accessibility, and permeability of urban form |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Transportation

Infrastructure (5%) |

Availability and

Accessibility of transportation modes |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Public

space design (10%) |

Quality,

Accessibility, and Diversity of public spaces |

4 |

5 |

|

|

Weightage |

32.1 |

35.7 |

||

|

Urban Context (40%) |

Location

(10%) |

Centrality,

Accessibility and Connectivity of location |

5 |

4 |

|

Urban density (15%) |

Population density and

Urban sprawl |

2 |

5 |

|

|

Land

use patterns (5%) |

Mix

and Balance of landuse |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Environmental

conditions (5%) |

Air quality, Water

quality and Access to green space |

5 |

3 |

|

|

Weightage |

40.8 |

46.8 |

||

|

Socio - Cultural Expressions (30%) |

Cultural practices

(10%) |

Diversity and Vibrancy

of cultural practices and traditions, such as arts, music and cuisine |

4.8 |

4.5 |

|

Social

values (10%) |

Adherence

to social values, such as respect for diversity, Inclusivity and Community

engagement |

4.5 |

4.2 |

|

|

Demographics (5%) |

Diversity and

inclusivity of the population in terms of gare,

gender, ethnicity and religion |

3.8 |

3.3 |

|

|

Socio

- Economic status (5%) |

Economic

opportunities and Social mobility, as well as Income

and wealth inequality |

5 |

4.5 |

|

|

Public participation

(5%) |

Level of civic

engagement, Community involvement and Public

decision making |

4.5 |

4.6 |

|

|

Total Score |

42.6 |

41.1 |

||

|

Source Authors |

||||

4.3. Analysis and Results

1) The

Built Form category, which has a weight of 30%, is divided into its several

subcategories in the table above. The Built Form category is used to assess a

city's physical attributes, such as building kinds, architectural styles, urban

morphology, transit systems, and public space layout. The weight and scoring

criteria for each subcategory vary. For instance, the Rome and Bhutan ratings

in the Building Types area are 4 and 3, respectively, and the subcategory has a

weight of 5%. Based on the variety and adaptability of building styles for

various functions, this subcategory's technique was developed. Lang (2005) and

Mohanty (2011) are some of the sources cited for this subcategory. Similar to

the subcategory of Architectural Style, which carries a 10% weighting, Rome and

Bhutan received ratings of 5 and 4, respectively. The variety and excellence of

architectural styles form the foundation of the methodology for this

subcategory. Kostof (1991) and Pallasmaa (2011) are

some of the sources cited for this subcategory. In general, the Built Form

category offers a thorough evaluation of a city's physical layout and

structure, taking into account a variety of elements including building types,

architectural styles, urban morphology, transit systems, and public space

design.

2) Urban

Context - Location, Urban Density, Land Use Patterns, Environmental Conditions,

and Economic Development are the five subcategories that make up the context

analysis category, which has a weight of 30%. The methods and weight for each

subcategory vary, and sources are given for additional background and

rationale. For instance, Rome and Bhutan both received scores of 4, which is

10% of the weight given to the subcategory of location. The centrality,

accessibility, and connection of the site are the foundations for this

subcategory's technique. Bertaud & Malpezzi (2003) and Soja (2010) are two sources

cited for this subcategory. The scores for Rome and Bhutan are 5 and 2,

respectively, in the subcategory of Urban Density, which has a 10% weighting.

This subcategory's technique is based on urban sprawl and population density.

McGranahan and Satterthwaite McGranahan & Satterthwaite (2014) and Pacione (2005) are some of the sources cited for this

subcategory. Context analysis gives a thorough evaluation of a city's livability and quality of life by taking into account a

variety of criteria including location, urban density, land use patterns,

environmental conditions, and economic development.

3) Socio-Cultural

Expressions-Cultural Practices, Social Values, Demographics, Socio-economic

Status, and Public Participation are the five subcategories that make up the

Socio-Cultural Expression Analysis category in this table, which has a weight

of 30%. The methods and weight for each subcategory vary, and sources are given

for additional background and rationale. For instance, Rome and Bhutan both

received scores of 4.5 and 4.8 in the Cultural Practices section, which has a

10% weighting. The technique for this subcategory is founded on the variety and

vitality of cultural practices and traditions, including art, music, and

gastronomy. Throsby (2001) as well as Zhang & Huang (2014) are cited as sources

for this subcategory. The rankings for Rome and Bhutan are 4.2 and 4.5,

respectively, under the subcategory of Social Values, which is similarly

weighted at 10%. The criteria for this subcategory is

founded on adherence to social ideals like respect for diversity, inclusivity,

and involvement in the community. Putnam (2000) and Sandercock (1998) are cited as

references for this subcategory. The weighted index calculation for the

Socio-Cultural Expression Analysis category, in general, takes into account a

variety of factors related to cultural practices, social values, demographics,

socio-economic status, and public participation, and offers a more nuanced

assessment of the livability and quality of life in a

city.

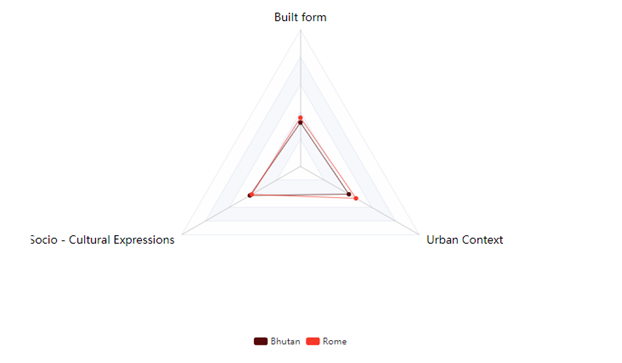

4.3.1. Results

The items for each subcategory and

category are added up to create the weighted index, which was then multiplied

by the corresponding weight to produce the overall scores:

The weighted index for Rome is (0.30 x

35.7) + (0.40 x 46.8) + (0.30 x 41.1), which is 123.6.

Bhutan's weighted index is calculated

as follows: (0.3 x 32.1) + (0.4 x 40.8) + (0.3 x 42.6) = 115.5

Rome gets a better overall score than

Bhutan according to this weighted index matrix. It's crucial to keep in mind

that this is only one interpretation and weighting of the criteria, and that

various scores or weights could provide different outcomes (Refer Figure 14).

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 Depiction of the

Result Analysis of Select Case Examples Source Authors |

5. Conclusion

Cities are dynamic, ever-evolving

entities that are not static. The spatial relationships between their many

components can change and evolve as they develop, taking on new shapes and

functions. This is evident in the ways that cities have developed and altered

over the years as a result of planning and design frameworks, social and

cultural norms, economic forces and new technologies. As a result, cities can

develop over time in a variety of forms, reflecting the unique characteristics

and identities of the people and cultures that inhabit within. However, despite

their continuing growth and change, cities continue to have an inherent sense

of continuity and historical significance. Many cities continue to possess

historic sites, buildings, public spaces, and infrastructure as part of their

built environment. Even while a city continues to grow and adapt in response to

new opportunities and challenges, its rich legacy helps it lend a sense of

belongingness and identity.

The reciprocal relationship and the

interconnectedness between the socio-cultural expressions, urban context and

the built environment emphasizes the critical consideration of it in the

planning, designing and the development of urban areas. This research study's

development of a weighted matrix index can be used as an effective checklist

technique for addressing urban planning and design from a comprehensive point

of view. The index provides a systematic and structured way to consider,

evaluate and prioritize different variables in order to facilitate

decision-making at multiple scales and levels by allocating weights to various

socio-cultural expressions, urban setting, and physical environment factors

that contribute to the overall character and identity of a city.

The weighted matrix index could be

applied at several scales and levels, including the design of single structures

or public areas as well as the development of entire communities or districts.

This tool would enable decision-makers to develop development schemes that are

not only functional but also meaningful and evocative of the distinct identity

of the community. According to their relative importance in a given situation,

the weighted matrix index gives several factors weights. For instance, cultural

significance can be given more weight than other considerations like economic

feasibility in a community where protecting cultural heritage is a major

priority. Decision-makers would be able to fabricate informed choices that

represent the particular requirements and goals of the community by comparing

various design solutions depending on how well they perform against these

weighted criteria.

Applying a weighted matrix index in urban planning and design essentially aims towards creating spaces that are vital and expressive of the community's distinctive identity in addition to being functional and economical. Decision-makers can contribute to the creation of cities that are more inclusive, sustainable, and equitable by comprehending the way socio-cultural expressions, urban context, and the physical environment are interconnected and using tools like the weighted matrix index to inform decision-making.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bertaud, A., & Malpezzi, S. (2003). The Spatial Distribution of Population in 48 World Cities: Implications for Economies in Transition. Housing Policy Debate, 14(1-2), 99-142.

Cuthbert, A. R. (2006). The Form of Cities: Political Economy and Urban Design. Blackwell Publishing.

Eldemery, I. M. (2009). Globalization Challenges in Architecture. Journal of Architecture and Planning Research, 26(4), 343-353.

Glaeser, E. L. (2011). Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier. Penguin.

Granham, T. &. Thomas, R. (2007). The Environments of Architecture: Environmental Design in Context. New Edition ed. London: Taylor & Franscis.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books.

Lynch, K. (1960). The Image of the City. Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press.

Masoud, N., & Guan, H. (2015). The Cultural Significance of Urban Form: An Analytical Study af Five Traditional Neighbourhoods in Cairo. Cities, 43, 16-30.

McGranahan, G., & Satterthwaite, D. (2014). Urbanization Concepts and Trends. In Planning Sustainable Cities: Global Report on Human Settlements 2009. Routledge. 3-18.

Naghizadeh, M. (2000). The Relationship (Traditional Iranian Architecture) Between Identity and Modernism and Modernity. Journal of Fine Arts, 7.

Niebuhr, G. (1851). The History of Rome. Vol. 1 ed. Philadelphia: Jmes Kay, Jun. & Brothers.

Pacione, M. (2005). Urban Environmental Quality and Human Wellbeing—A Review of Recent Developments. Geography Compass, 1(4), 717-735.

Parvizi, E. (2009). National Architecture from the Perspective of Cultural Identity. Journal of National Studies, 3.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community. Simon and Schuster.

Radstrom, S. (2011). A Place - Sustaining Framework for Local Urban Identity: An Introduction and History of Cittaslow. Journal of Planning Practice, I (1-2011), 90-113.

Robinson, B. R. (2017). www.current affairs.org. [Online].

Rossi, A. (1982). The Architecture of the City. Revised Edition ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Sandercock, L. (1998). Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities. John Wiley & Sons.

Soja, E. (2010). Seeking Spatial Justice (Vol. 1). University of Minnesota Press.

Throsby, D. (2001). Economics and Culture. Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, J., & Huang, Y. (2014). Assessing Cultural Vitality in Rural China: A Case Study of Ya’an City, Sichuan Province. Sustainability, 6(10), 7329-7349. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9110467.

Ziolkowski, A. (2013). Civic Rituals and Political Spaces in Republican and Imperial Rome. In P. Erdkamp (Ed.), The Cambridge to Ancient Rome(Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 389 – 409. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781139025973.028.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.