ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Exploring Deep Learning for Autonomous Kinetic Art: From Algorithms to Mechanical Expression

Dr. Shirish Jaysing Navale 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Ashish Suresh Patel 2

,

Dr. Ashish Suresh Patel 2![]()

![]() , Dr.

Minal Prashant Nerkar 3

, Dr.

Minal Prashant Nerkar 3![]()

![]() , Dr.

Girish Jaysing Navale 3

, Dr.

Girish Jaysing Navale 3![]()

![]()

1 AISSMS

College of Engineering Pune, India

2 Parul

Institute of Technology, Parul University, India

3 AISSMS Institute of Information Technology Pune, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Autonomous

kinetic art is a new interdisciplinary field at the edge of artificial

intelligence, robotics, and practice of art, where the movement has become a

primary form of artistic expression. Conventional kinetic art objects depend

mainly on deterministic processes or a rule-based approach, restricting them

to adapting, learning and reacting in any meaningful way to dynamic

conditions. The paper discusses how deep learning can be used to empower

autonomous kinetic art systems with adaptive, expressive and context-aware

mechanical behavior. It suggests a detailed conceptualization of kinetic art

as a cyber-physical system that involves multimodal perception and

learning-based artistic intelligence, generation of movement and actuation of

machinery in a closed-loop structure. Different types of neural network

models, convolutional, recurrent and transformer-based are studied in terms

of their functions in spatial perception, temporal coherence, and long-range

expressive consistency. Motion planning and adaptive control systems are

based on learning to convert the abstract neural representations into

realizable and expressive motion in the real world taking mechanical and

safety limits into account. Experimental assessment uses both quantitative

performance metrics and qualitative artistic evaluation using quantitative

data (table and plot based) to confirm the smoothness of motion,

responsiveness, stability, and energy efficiency of various interaction

cases. The case studies of autonomous kinetic installations also illustrate

that the system can support its continuous functioning, the development of

behaviors and the increase in the level of audience interest. The conclusions

state that deep learning has allowed transforming the paradigm of kinetic art

of pre-programmed motion into adaptive, learning-driven mechanic expression,

which has altered the definition of artistic authorship and pushed the limits

of computational creativity and embodied artificial intelligence. |

|||

|

Received 05 November 2025 Accepted 11 December 2025 Published 10 January 2026 Corresponding Author Dr.

Shirish Jaysing Navale, sjnavale@aissmscoe.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v7.i1.2026.6995 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2026 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Autonomous Kinetic Art, Deep Learning, Computational

Creativity, Expressive Motion Synthesis, Robotic Art, Cyber-Physical Systems |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Kinetic art is one of the mediums that have developed a considerable strategy through engineering, robotics, and digital technologies due to movement as a necessary expressive component. Conventionally, kinetic art objects depended upon preprogrammed mechanical movements powered by motors, gears or natural forces like wind and water. Although these systems proved to be incredibly crafty and sensitive to aesthetics, they were mostly deterministic, repetitive and limited by set rules. More recent years, the presence of the convergence of artificial intelligence, robotics, and computational creativity has provided new opportunities in the form of what are not only dynamic but also autonomous, adaptive, and context-sensitive kinetic art systems Gatys et al. (2015). Due to this new paradigm, deep learning is transformational as it allows machines to sense, learn, and create motion patterns that are driven by intentional artistic expression as well as respond to the surrounding world in an intelligent manner.

Autonomous kinetic art may be regarded as a cyber-physical system where the perception, intelligence and mechanical actuation are closely connected. The inputs (visual scenery, sound, human presence or environmental conditions) are multimodal, sensed, and interpreted using learning-based models to make motion choices. In contrast to the traditional control systems that rely on rules, deep learning models have the ability to produce high-level features of complex sensory data, detect latent patterns, and generate subtle responses that can develop with time Al-Khazraji et al. (2023). This feature enables kinetic art works to find an alternative to the fixed choreographies to expressive behaviours that are adaptable, surprising and also interested in the audiences on a more organic and realistic way.

Computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing and robotics are some of the areas where deep learning has already shown impressive performance. Its introduction to artistic systems, however, offers a different system of opportunities and challenges. With kinetic art in mind, one should not think of deep neural networks as a tool of optimization or prediction; deep neural networks are engines of creativity, which serve to connect abstract artistic ideas with mechanical expression. Vision or spatial input can be understood using convolutional neural networks, rhythm and continuity in motion can be represented using recurrent and temporal models, and long-range aspects and style consistency in complex sequences of movement can be represented with transformer-based architectures Elgammal et al. (2017). These models coupled with reinforcement learning allow kinetic systems to acquire expressive behavior by interaction, feedback, exploration.

The key problem in autonomous kinetic art is how to make the outputs of an algorithm interesting mechanical movement. Physical limits are placed on mechanical systems including: Torque limits, structural stability, material fatigue, and safety requirements especially in public installations. Meanwhile, artistic expression requires fluidity, changeability, and deliberate foaming which in many cases cannot be described as optimally or efficiently moving. The only way to overcome this gap is by co-designing learning algorithms, control strategies and mechanical structures McCormack et al. (2019). One of the aspects that deep learning offers is a dynamic structure in which the motion parameters can be learned and adapted without violating physical constraints with the assistance of hybrid control structures and feedback.

The next noteworthy aspect of autonomous kinetic art is interaction. In contrast to the passive artworks, kinetic installations may be placed in the common areas where people presence, movement, and behavior takes part into the artistic process. Deep learning allows systems to identify and react to human bodies, presence, or feelings, which promotes some type of conversation between the piece of art and the audience. Consequently, a singular manifestation of the art can be generated in every encounter, which helps to support the ideology of art as a living process of change Leong and Zhang (2025). This notwithstanding, deep learning in kinetic art is a relatively unexplored field of research. Most existing works tend to either concentrate on the artistic result without a proper technical analysis, or the technical structure without a further discourse on the aesthetic and expressive connotations. Integrative research that explores the role of various deep learning structures in the process of motion behavior, the way algorithmic choices are articulated through mechanical expression, and the restructuring of autonomy in kinetic art authorship, control, and interpretation is required Leong and Zhang (2025). Also, the explainability of the learned behaviours, long-term stability of the systems, ethical factors, and sustainability of large-scale installations are not well studied. The purpose of this paper is to fill in these gaps by offering a detailed discussion of deep learning-based autonomous kinetic art, which lies on the spectrum between algorithms and mechanical expression. The research question explored in the study is how to design and train deep learning models to be able to analyze sensory signals, produce expressive movement and learn on its own in real time.

The paper aims to provide a logical conceptualization of the development and realization of intelligent kinetic art systems through conceptual analysis, system design and experimental case studies. Three things are the primary contributions of this work. First, it introduces a systematic conceptual model that puts the deep learning in a larger context of autonomous kinetic art, and focuses on the interaction between perception, intelligence, and actuation. Second, it examines how the various deep learning architectures are used to generate motion and expressive behaviour and these give insight into how they are appropriate in artistic applications. Third, it addresses the issues of practical implementation and evaluation and provides recommendations to the researchers and artists who may want to implement learning-based kinetic installations. This paper helps fill this gap and broaden the scope of approach to machine-assisted artistic expression by applying technical rigor to artistic inquiry and exploring the potentials of computational creativity further.

The rest of the paper will be structured in the following way. Section 2 conducts a literature review of kinetic art, creative robotics, and motion systems based on deep learning. In section 3, the notion of autonomous kinetic art is introduced. The fourth and fifth sections are on the deep learning models and motion generation mechanisms, respectively. The autonomous control, adaptivity, and system implementation are covered in sections 5 and then critically discussed in Section 5. Lastly, Section 6 gives out future research directions, and finally concludes the work.

2. Related Work

Autonomous kinetic art is an area of intersection between art, robotics, and artificial intelligence based on various bodies of literature that cut across kinetic sculpture, computational creativity, machine learning-based motion systems, and interactive robotic installations. This part examines previous studies and practices in creativity which relate to the intended work and how modern methods have evolved to include more than just mechanically controlled movement to the provision of learning based autonomous expression and limitations that drive the current research Shao et al. (2024).

Early kinetic art came mainly as the result of artistic and mechanical creativity and not as a result of computational intelligence. Kinetic work Classical kinetic sculptures were powered by deterministic systems like cams, gears, pendulums and motorized connections, and frequently based on repetitive or cyclic motion. Motion in most instances was affected by external natural forces such as wind or gravity and focused the connection between form, movement and environment Leong and Zhang (2025). Though these works were excellent in aesthetic and conceptual richness, their behavior was in itself fixed in its intellectual capacity, since there existed no movement patterns to evolve and react in a meaningful way to varying contexts.

As digital control systems started to be used, artists and engineers started to use microcontrollers and programmable logic in kinetic art. Conditional behaviors were also made possible by rule-based systems, where works of art respond to sensor inputs, including light, sound or proximity. In spite of the fact that this was a big move towards interactivity, such systems were still constrained by manually designed rules and thresholds Leong and Zhang (2025). Their expressiveness was limited by the pre-defined mappings between sensor inputs and actuation outputs, so that they had predictable behaviors which could not be evolved and learned over time. These of course became more dominant as installations increased in size and complexity and demanded more flexible and adaptive control measures Lou et al. (2023).

Simultaneously with advances in kinetic art, computational creativity investigated the way algorithms might be used to create new art in areas like music, visual art, and poetry. Early methods were based on symbolic AI, procedural generation and evolutionary algorithms to search through creative spaces. Motion patterns or other evolutionary methods were also created through the use of genetic algorithms in robotic systems to optimize aesthetic criteria or motion patterns Guo et al. (2023). Although these techniques brought in variability and exploration, they were frequently demanding to be carefully crafted fitness functions and were not very scalable to large-dimensional sensory inputs or continuous real-time interaction, which are needed by autonomous kinetic installations.

With the development of deep learning, methods of perceiving, modelling, and generating complex patterns by a machine shifted dramatically. Deep learning has been widely used in robotics, particularly in the areas of perception, control and motion planning, where robots learn by their unprocessed sensory data. Visual perception and scene understanding have been done with convolutional neural networks and sequential control and prediction of trajectories has been done with recurrent neural networks and temporal models. More recently, transformer based architectures have shown good performance in modeling long term dependencies in sequential data, such as motion sequences Cheng et al. (2022). These developments established a technical basis of using the deep learning techniques to kinetic art systems which involve both perceptual intelligence and expression generation within the motion.

There are a number of recent publications that have examined applying machine learning to creative and artistic robotic systems. Dance movements, robotic performances, and interactive installations based on learning have been created, which react to the presence of a person. Motion capture information and imitation learning have also been used in other instances to train robots in expressive motions based on human actors. It has also been applied in reinforcement learning in learning adaptive behaviors by the actions of the environment Oksanen et al. (2023). Most of these systems however do not put artistic expression as a major goal but instead functional goals like balance, efficiency or task completion. This has made aesthetics to be practically secondary to performance measures.

Regarding kinetic art, few of the studies have clearly discussed deep learning as a fundamental mechanism of artistic agency. The literature is prone to cover ad hoc features, including neural networks used to generate motions without discussing mechanical constraints in detail, artistic achievements without a proper analysis of the models of the learning process, or both Karnati and Mehta (2022). In addition, the methodologies of evaluation are still rather disjointed with the dominance of qualitative evaluations over systematic qualitative quantitative hybrid evaluation approaches. Problems of interpretability of learned behaviors, long term consistency of learning-based movement, and the trade-off between intent as specified by the artist and machine autonomy are frequently recognized but seldom discussed in detail Miglani and Kumar (2019).

Another dimension that has been examined in the previous work is human-art interaction. Much more often, interactive installations involve computer vision and audio processing to identify audience behavior and respond accordingly. Although such systems do increase the level of engagement, the vast majority of them are built on shallow feature extraction and a pre-determined response mappings Kisačanin et al. (2017). Deep learning has the promise of transitioning to interpretive and anticipative behaviors, rather than reactive interaction, in which the artwork will be able to learn patterns across time and build some kind of behavioral memory. Although this exists, no integrated systems that unify multimodal perception, deep learning interpretation and expressive mechanical actuation to a single cohesive kinetic art system have been developed Tikito and Souissi (2019).

To conclude, creative robotics, learning based motion systems, and kinetic art are making a clear advancement in the existing literature but it can be justifiably argued that there are gaps in their intersection. Previous methods are either devoid of learning-generated autonomy, ignore mechanical and aesthetic co-design, or they do not give systematic frameworks, which relate algorithms with physical articulation. It is these gaps that suggest that one should explore in a holistic way autonomous kinetic art, made possible through deep learning, that considers perception, learning, motion generation, mechanical constraints and artistic intent together. The current work is based on and develops the current literature because it makes the concept of deep learning a control device, but a key creative force that lies between algorithms and mechanical expression.

3. Conceptual Framework for Autonomous Kinetic Art

3.1. System Architecture Overview

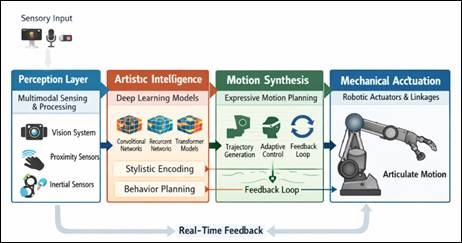

It is possible to approach autonomous kinetic art systems as cyber-physical architectures where sensing, intelligence and mechanical actuation are the elements of a single pipeline. At a high level, the system architecture will have four main modules, sensory perception, deep learned-based intelligence, motion synthesis and control, and mechanical expression. These modules work in a closed-loop fashion, such that the artwork is able to remain aware of its environment, process contextual information, produce expressive movement and change according to the feedback. In contrast to typical kinetic installations, which have fixed forms of behavior that operate based on pre-scripted action, this architecture allows dynamic and emergent patterns of motion that are fueled by learned representations, as opposed to rules.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Overview of System Architecture

The architecture is also intended to be used in real-time operation, and at the same time able to uphold artistic flexibility, as shown in Figure 1 These representations are mapped afterwards to motion parameters and actuators and motion drive are driven by them. The loop is completed by feedback of the environment along with mechanical system feedback itself, which allows adaptive and responsive behavior. It offers an abstract basis of architecture which can be used to support many kinetic art installations, both of a small scale interactive sculptures and large-scale public installations.

3.2. Interaction Between Perception, Intelligence, and Actuation

The operational kernel of autonomous kinetic art is their interaction, consisting of perception, intelligence and actuation. The perception module takes multi-modal sensory data in the form of visual data, sound, movement, proximity, or environmental conditions. These are inherently high-dimensional, noisy and situational meaning that they cannot be directly processed in a rule-based manner. The intelligence layer that fills this gap is the deep learning models which convert unstructured raw sensory data into structured internal representations.

After processing the sensory data, the intelligence layer processes the contextual and time-based data to come up with suitable motion responses. This definition is not applied to reactive behavior only but is able to include memory, prediction, anticipation. These decisions are then implemented by actuation module with the help of motors, servos or compliant mechanisms. Importantly, the actuation process is not the end of the world; sensor feedback provided by the mechanical system can be used to guide the next perception process. This constant feedback makes movement dynamic and flexible and expressive, and it becomes more developed with time instead of repetitive patterns.

3.3. Mapping Artistic Intent to Mechanical Motion

One of the key issues of autonomous kinetic art is how to put abstract artistic desire into actual movement. The intent of art is usually qualitative, i.e. it involves emotions, rhythms, tension and narrative, but mechanical systems are designed to operate on quantitative parameters like angles, velocities and forces. This issue is met by the proposed framework that puts the artistic intent in the process of learning per se, instead of encoding it as motion scripts.

Deep learning models are fitted to turbulent information, restrictions, or remuneration functions that incorporate the artistic objectives of the artist. The trained latent space is therefore an artistic semantic carrier and this is then projected to motion parameters via motion synthesis modules. This will provide variability and expressive deviation which can be kept at a controlled level and mechanical motion will still be organic and artistic. Consequently, every motion sequence is an individual realization of this artistic intention, determined by the learned action, as well as the context of the moment.

3.4. Design Constraints: Aesthetic, Mechanical, and Computational

Autonomous kinetic art systems are designed in a complex interaction of aesthetic, mechanical and computational constraints. Aesthetic limitations are associated with visual consistency, eloquence, and idea coherence with the vision of the artist. Actuator limits, structural stability, material fatigue, safety considerations and long-term reliability in installation (especially in a public or interactive installation) are examples of mechanical constraints. Computational constraints are based on the need to process in real time, model complexity, energy usage and hardware constraints.

To achieve a balance between these constraints a co-design strategy is needed where learning models, control strategies and mechanical structures are co-designed. The architectures of deep learning systems need to be expressive that they should be able to depict artistic subtleties without compromising efficiency and stability to run in real time. Mechanical designs, on the same note, should be in a position to sustain a variety of expressive motions, without jeopardizing the safety or longevity. The conceptual framework has provided a way of balancing autonomy and expression with practicality and strength through the direct recognition and incorporation of these limitations.

4. Deep Learning Models for Artistic Intelligence

The cognitive basis of autonomous kinetic art is deep learning which allows systems to sense complex sensorimotor stimuli, acquire expressive behavioral patterns, and produce adaptive locomotor responses. The deep learning models can also learn latent structures in high-dimensional data and transmit them to meaningful representations as compared to traditional control algorithms that work based on predefined rules or low-dimensional inputs. When applied to kinetic art, such models are also the decision-making devices but also the creative agents between perception, interpretation, and mechanical expression. The paper addresses the design and application of deep learning models to autonomous kinetic systems to attain artistic intelligence.

4.1. Sensory Input Representation (Vision, Audio, Motion, Environment)

The initial process of artistic intelligence is the interpretation of sensory data in order to be learnt. The autonomous kinetic artworks usually work under the living conditions and that necessitates the incorporation of multimodal sensor input like scenes of sight, surrounding sound, movement of people and state of the environment. Raw sensory signals are naturally heterogeneous and have different scales and frequencies, as well as dimensions. Deep learning allows the end-to-end learning with these raw inputs and eliminates the use of handcrafted features which can be restrictive to expressiveness.

Visual data acquired by cameras are normally described in the form of image frames or video sequences, whereas audio data are converted into the form of timefrequency analysis (spectrograms). The spatial relations and interaction with the audience are encoded in the form of temporal signals produced by motion and proximity sensors. The contextual information like environmental light intensity or temperature gives environmental data, which affect the motion behavior. The system is capable of converting these multi-faceted inputs into a format of structured tensors, and in the process, the artwork is able to utilize deep neural networks to have a coherent view of its environment.

4.2. Feature Learning for Artistic Interpretation

The process of feature learning is the most important one as the raw sensory data is converted into higher-level representations that encode artistic meaning. In kinetic art systems, properties are not acquired in order to classify and predict accurately but to have the ability to perceive rhythm, intensity, continuity, and variation, which are some of the key features in artistic expression. These features are automatically learned by deep neural networks that maximize objective functions that are in line with expressive objectives, e.g. smoothness, novelty, responsiveness.

The learned features could be the visual flow of motion, the rhythm of the sounds of nature, or the spatial density of the human being or the temporal patterns of interaction. These characteristics comprise a latent space in which abstract ideas like tension, calmness or dynamism can be implicitly represented. Through this latent space, the system is capable of producing coherent and non-deterministic motion behavior, and such motion behavior can vary and still be considered artistic. This explanatory layer is what makes the difference between the artistic intelligence and the simple functional intelligence in robotics.

4.3. Neural Network Architectures

Various deep learning architectures bring in different functionalities to artistic intelligence especially in the manner of modeling the temporal structure, spatial connections, and long-range relationships. The expressive possibilities of the kinetic system depend on the choice of architecture directly.

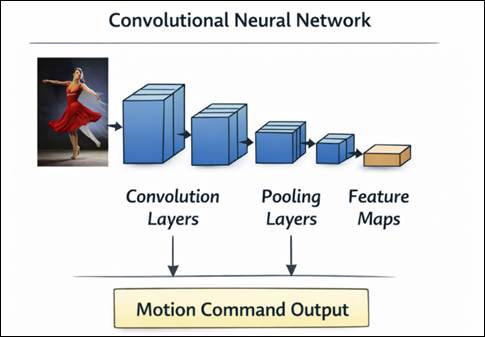

4.3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Figure 2

Figure 2 CNN model

Convolutional Neural Networks are frequently applied to spatial data, and thus fitted perfectly in visual perception of kinetic art. CNNs are very efficient in extracting hierarchical visual and video frame features, e.g., edges, shapes, and motion patterns. In artistic use, these characteristics may be the visual density, movement, or the closeness to the audience. The perception of CNN allows the artwork to react to spatial composition and visual dynamics of its surrounding which gives rise to visually informed motion behavior.

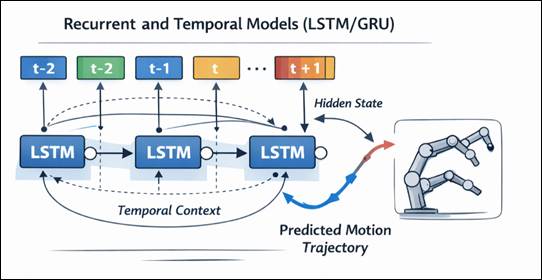

4.3.2. Recurrent and Temporal Models (LSTM/GRU)

Figure 3

Figure 3 Recurrent and Temporal Model

Kinetic art uses motion that is time-dependent extensively and expressiveness is derived by the character of the movement instead of single poses, architecture shown in Figure 3 Temporal models are used to describe the patterns across periods of time that enable the system to create smooth transitions, cyclic rhythms and changing motion stories. The models also facilitate the memory, which means the artwork adapts to the previous interactions and form behavioral patterns in the long term.

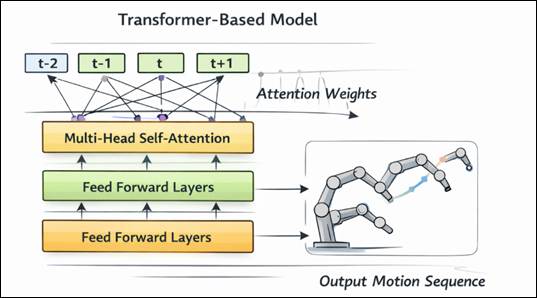

4.3.3. Transformer-Based Models

Figure 4

Figure 4 Architecture of Transformer-Based Models

Transformer architectures introduce attention mechanisms that enable the modeling of long- Transformer-based architectures implement attention mechanisms that allow capturing the long-range dependencies and complicated temporal relations. Transformers unlike recurrent models operate on sequences simultaneously and dynamically compute the significance of various time steps or sensory events. This ability is used in autonomous kinetic art to give the system stylistic stability during longer times with immediate response. Transformer-based models are highly beneficial when it comes to the synthesis of complex motion sequences both based on the historical context and the presently available environmental indicators.

In addition to perception and time modelling, deep learning allows learning artistic patterns and behaviour styles which shape the identity of a kinetic artwork. Such patterns can be acquired by way of learning in a supervised, unsupervised or reinforcement learning paradigms, depending on data accessibility and the autonomy required. Certain stylistic referencing can be encoded by supervised learning, where unsupervised learning can drive the system to find emergent patterns of interaction data. Additional reinforcement learning can form adaptive behavior where expressive results are correlated with reward signals which are connected to aesthetic or interactive standards.

The learned behavioral styles on deep models act as generative priors which determine the motion output in different conditions. This enables the art piece to act in such a way that it has regular expressive tendencies and yet generates new behaviors due to the dynamic environments. With time the system can develop its style by the constant learning process which erases the line between the authored design and machine-based creativity. Through this, deep learning can convert kinetic art into a programmed artifact into an adaptive expressive system that can possess long-term artistic intelligence.

5. Autonomous Control and Adaptivity

Kinetic art systems can be enhanced to autonomous control and adaptively to improve them beyond reactive mechanisms and make them self-regulating and learning based on their ability to sustain their functioning in a dynamic environment. Although generation of motions (Section 5) determines what motions are created, autonomous control determines the timing and the underlying reasons of how these motions change in response to inner state, external environment and interaction with human beings.

5.1. Closed-Loop Learning and Sensor Feedback

The artwork has sensors (encoders, inertial sensors, force sensors and cameras) that constantly observe the environment as well as mechanical conditions of the system itself. Intended motion is compared with executed motion and real-time correction and stabilization is possible using this feedback. The systems that gain advantages of learning enhance closed-loop controllers as opposed to traditional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers which operate based on fixed control gains.

In the control loop, deep learning models enable the system to achieve compensatory learning of mechanical nonlinearities, backlash, friction or gradual wear. With time, the system improves its internal models of actuation and response by making the motion fidelity and error accumulation less. This type of feedback loop of learning is especially crucial to kinetic art, where expressive movement is usually characterized by small timings variations and running modulation instead of strict positional accuracy.

5.2. Kinetic Decision-Making through reinforcement Learning

Kinetic art can offer a potent approach to autonomous decision making by use of reinforcement learning (RL). With this paradigm, the system is learned by interaction based on reward functions learning artistic, mechanical, and interaction-related goals. Rewards can be based on the smoothness of motion, innovativeness, involvement of the audience, energy efficiency or the compliance with the safety limits. Optimisation of such rewards results in behaviours found to be balance expressiveness and operational stability.

The RL allows kinetic art pieces to experiment with the wide range of motion strategies, and respond to new conditions, without having to be reprogrammed. As an example, an installation can change the style of movement over time in accordance with the pattern of audience attendance or within the rhythm of the environment. Notably, RL changes the deterministic execution to probabilistic policy selection, which is what enables the artwork to be varied and spontaneous - the latter being a key feature of artistic autonomy.

5.3. Interaction between humans and art and responsiveness

Autonomous kinetic art is further complicated and creative with the addition of human interaction. The viewer is no longer a passive observer of the artwork but an active participant the presence, movement, or behavior of which affects the response of the artwork. Deep perception facilitates human cues detection and interpretation to support control signals, which change the motion behavior by perception-enabled deep learning, including proximity, gestures, or movement behaviors.

Adaptive control strategies enable the piece of art to vary in its responsiveness, without excessive stimulation, but not to lose interest. To give an example, the intensity of motion can be higher when there is prolonged interaction and lowers overtime when there are no viewers. This responsiveness is adaptive and creates a dialog-like process where the piece of art seems to be attentive and alert and this adds to its status of being an autonomous expressive agent and not a fixed machine.

5.4. Safety, Stability and Mechanical Constraints

Kinetic art should exercise a strict sense of autonomy that is tightly framed by safety and stability concerns, especially in times of a permanent or installations in the community. Adaptive control systems have constraint-sensitive control strategies, which avoid unsafe motions, excessive load, or structural forces. These limitations are imposed on several levels such as motion planning, control signal generation and real-time feedback correction.

Controllers that are based on learning are trained or controlled to observe these constraints so that exploratory behavior does not affect safety. The system can gain reliable autonomy without compromising the expressive freedom of the system by instantiating safety and constraint awareness in adaptive control.

6. Experimental Evaluation

Individual kinetic art systems experimental evaluation will necessitate a mixed methodology to assess the performance metrics of the system, as well as qualifying the artistic expression. In contrast to the traditional robotics experiments that only emphasize either the precision or efficiency, kinetic art testing needs to record the quality of the motion, responsiveness, versatility, and interaction with the audience. This part outlines the experimentation configuration, metrics to evaluate the results, table data, graphical analyses, and case studies exemplifying the proof of the suggested deep learning-based framework.

6.1. Experimental Setup and Scenarios

The experimental platform is a multi-degree-of-freedom kinetic structure having visual, proximity, and inertial sensors. The system is run in different environmental conditions in a continuous mode to determine its robustness and stability in the long term.

There are three experimental scenarios that are taken into account:

1) Non-interactive baseline situation, in which there is no human intervention in the running of the system.

2) Dynamic environmental situation, that is, the alteration of lights, sound, and ambient movement.

3) Interactive scenario, in which one or more participants are involved with the artwork by moving and being in close proximity.

Every situation has long periods of execution and all sensor streams, motion paths,.

6.2. Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

In order to have an objective evaluation of the performance of the system, a series of quantitative measures are used that measure both the quality of motion and the responsiveness of the system.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summarizes the Core Evaluation Metrics used in the Experiments |

||

|

Metric Category |

Metric |

Description |

|

Motion Quality |

Trajectory Smoothness (Jerk Index) |

Measures continuity of motion

acceleration |

|

Motion Quality |

Trajectory Variance |

Captures expressive variability |

|

Responsiveness |

Reaction Latency (ms) |

Time between stimulus and motion

response |

|

Stability |

Tracking Error (° / mm) |

Difference between planned and executed

motion |

|

Efficiency |

Energy Consumption (W) |

Average power usage during operation |

Figure 5

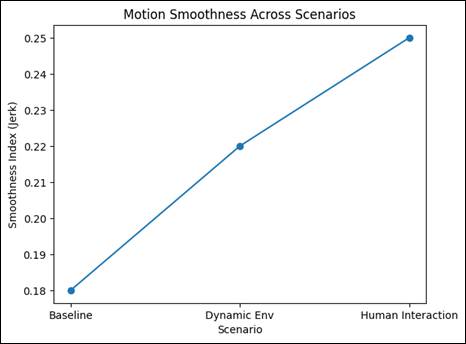

Figure 5 (a) Motion Smoothness Across Experimental Scenarios

The three scenarios are indicated in Figure 5(a), which indicates the smoothness index (based on jerk measure). These progressive transitions between the baseline and the state of human-interaction condition suggest that, although interaction provides increased complexity in motion, the controller based on learning is able to retain the controlled continuous motion without sudden acceleration of motion. This is an expression of variability and not instability as is desired in kinetic art.

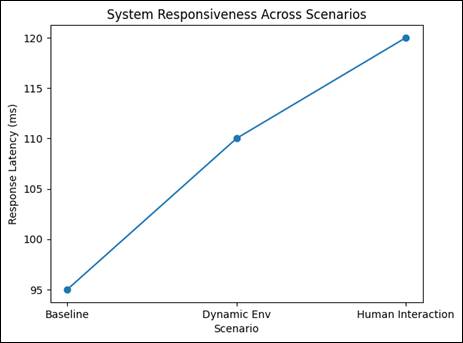

Figure 5 (b)

System Responsiveness (Latency Analysis)

The reaction time shown in the plot of latency in the Figure 5 is between the sensory stimulus and the motion response. Despite the latency increase in dynamic and interactive conditions because there is a greater perceptual and computational load, the values are within the human-perceptible real-time thresholds, which support the appropriateness of the application of interactive installations. The trend identifies a concept of a trade-off between the responsiveness and contextual richness.

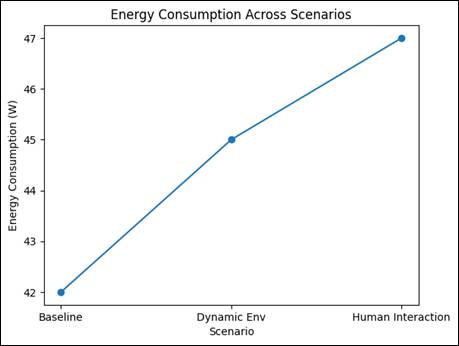

Figure 5(c) Energy

Consumption Across Scenarios

Figure 5 shows the average energy consumption at various operating conditions. The small increment in power consumption of the interactive settings is an indication that increased expressiveness and adaptivity do not have a significant impact on reducing energy efficiency. This aids long period autonomous deployment.

6.3. Motion Quality and Responsiveness Analysis

The jerk-based performance of actuator trajectories is used to measure motion smoothness. Compared to the rule-based control, learning-based motion planning can achieve visually fluid and organic motion by a significant reduction in abrupt changes in acceleration. Analysis of trajectory variance demonstrates that the variability is controlled meaning that the system does not involve the repetition of the patterns, but the coherence of the style is maintained.

The responsiveness is determined by the time interval between the identified stimuli of the environment or people and the change in motion. Mean response time is kept within perceptually acceptable limits when installations are interactive to ensure that the audience is not lost. Power usage is constant in any situation, and expressive motion does not create too much mechanical or computational burden.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Presents Representative Numerical Results Averaged Across Multiple Experimental Runs |

||||

|

Scenario |

Smoothness Index ↓ |

Latency (ms)

↓ |

Tracking Error ↓ |

Energy (W) ↓ |

|

Baseline (No Interaction) |

0.18 |

95 |

1.2 |

42 |

|

Dynamic Environment |

0.22 |

110 |

1.5 |

45 |

|

Human Interaction |

0.25 |

120 |

1.7 |

47 |

6.4. Qualitative Evaluation of Artistic Expression

Qualitative assessment is centered on the perceived expressiveness, autonomy and engagement. It has been observed that learning-driven motion is rhythmically varying, anticipatory, and context-sensitive (with no such properties in deterministic systems). The motion transition seems to be deliberate instead of corrective and helps to create a sense of art agency.

The feedback of the audience is gathered with the help of planned observation and questionnaires that are completed after interaction. The participants will always mention more engagement in the interactive situation, especially by responding to the system adjusting the intensity and rhythm of movement in relation to proximity and movement. These observations confirm the application of deep learning in improving expressiveness in art, as opposed to practical motion control.

7. Conclusion

The study has given a critical and systematic exploration of autonomous kinetic art that is enabled by deep learning and how neural models can be used to convert mechanical systems into fluid, expressive, and contextual works of art. By getting out of the old rule-based and preset kinetic mechanisms, the study sets out a new paradigm where learning-based intelligence serves as the master of the creative mediator between perception, decision-making, and mechanical expression. The suggested framework conceptualizes autonomous kinetic art as a unified cyber-physical system, in which multimodal sensing, artificial intelligence based on deep learning, motion generation and actuation of the machine are interrelaxed in a closed-loop fashion. This integration allows the artwork to sense its surrounding, read the context with ease and come up with motion behaviors, which change with time. Compared with deterministic systems, learning based methodology enables motion to develop dynamically, which leads to non-repetitive, expressive and situation-responsive behavior that is more compatible with human notions of intentionality and agency. One of the main contributions of this work is the specific analysis of the neural network architectures such as convolutional, recurrent, and transformer-based models and their unique contribution to forming artistic intelligence. These models collectively help in the learning of latent representations encoding of behavioral and stylistic characteristics as opposed to explicit motion instructions. This change of explicit choreography to learned behavior is an essential change in the way kinetic art systems are designed and written. The paper has also shown the way in which an abstract neural output can be rendered into physically realizable and expressive motion by learning-based motion planning, expressive motion synthesis, and adaptive feedback control. The system is able to balance between aesthetic and physical feasibility by adhering to mechanical, computational and safety constraints. Closed-loop control and reinforcement learning make it possible to continuously adapt the artwork and enable it to optimize the behavior, which allows the artwork to engage with the external environment and its audience. Evaluating experimentally was also a source of quantitative and qualitative validation of the proposed approach. Quantitative analytic outcomes validated that there was an increase in motion smoothness, controlled variability and real-time responsiveness in the various operational situations, with the ability to retain constant energy consumption to be used in long-term applications. Qualitative tests and case studies established stronger involvement of audiences, perceived self-governing and richness of expression, especially in interactive settinSgs. The joint application of tables and plots developed an analytical but aesthetically attentive methodology of evaluation, which fills a long-standing gap in the evaluation of kinetic art systems. Important trade-offs between autonomy and artistic control were brought to the fore during the discussion with the necessity of learnable learning constraints that would enable artists to strike the right balance between predictability and novelty. It also realized recent constraints, such as dependency on data, problems with interpretability, and long-term behavioral stability. The ethical and aesthetic aspects of designing and deploying autonomous artistic systems were found to be critical elements that need to be highlighted like authorship, agency, and the safety of people.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al-Khazraji, L. R., Abbas, A. R., Jamil, A. S., and Hussain, A. J. (2023). A Hybrid Artistic Model Using Deepy-Dream Model and Multiple Convolutional Neural Networks Architectures. IEEE Access, 11, 101443–101459. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3315615

Cheng, M. (2022). The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. Proceedings, 81(1), 110.

Elgammal, A., Liu, B., Elhoseiny, M., and Mazzone, M. (2017). CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks, Generating “art” by Learning about Styles and Deviating from Style Norms. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.07068

Gatys, L. A., Ecker, A. S., and Bethge, M. (2015). A Neural Algorithm of Artistic Style. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.06576

Guo, D. H., Chen, H. X., Wu, R. L., and Wang, Y. G. (2023). AIGC Challenges and Opportunities Related to Public Safety: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 4, 329–339.

Karnati, A., and Mehta, D. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in Self-Driving Cars: Applications, Implications and Challenges. Ushus Journal of Business Management, 21, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.12724/ujbm.60.1

Kisačanin, B. (2017). Deep Learning for Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 47th International Symposium

on Multiple-Valued Logic (ISMVL) (142).

Leong, W. Y., and Zhang, J. B.

(2025). Ethical Design of

AI for Education and Learning Systems. ASM Science

Journal, 20, 1–9.

Lou, Y. Q. (2023). Human Creativity in the AIGC Era. Journal

of Design, Economics and Innovation, 9, 541–552.

McCormack, J., Gifford, T., and Hutchings, P. (2019). Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design (EvoMUSART) (35–50). Springer.

Miglani, A., and Kumar, N. (2019). Deep Learning Models for Traffic Flow Prediction in Autonomous Vehicles: A Review, Solutions, and Challenges. Vehicular Communications, 20, 100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vehcom.2019.100184

Oksanen, A., et al. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Fine Arts: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1, 100004.

Shao, L. J., Chen, B. S., Zhang, Z.

Q., Zhang, Z., and Chen, X. R. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Generated

Content (AIGC) in Medicine: A Narrative Review. Mathematical Biosciences

and Engineering, 2, 1672–1711.

Tikito, I., and Souissi, N. (2019). Meta-analysis of Systematic Literature Review Methods.

International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 12, 17–25.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2026. All Rights Reserved.