ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Management Innovation in AI-Driven Art Ecosystems

Mazin Nawwaf Assi 1![]()

![]() ,

Sumeet Kaur 2

,

Sumeet Kaur 2![]()

![]() ,

Swati Chaudhary 3

,

Swati Chaudhary 3![]() , Dr. Pompi das Sengupta 4

, Dr. Pompi das Sengupta 4![]()

![]() ,

Palak Patel 5

,

Palak Patel 5![]()

![]() ,

Balaganapathy Perambur Sambandan 6

,

Balaganapathy Perambur Sambandan 6![]()

![]() , Amrut Ramchandra Pawar 6

, Amrut Ramchandra Pawar 6![]()

1 Department

of Supply Chain and Logistics Management, Al-Zaytoonah University of Science

and Technology, Palestine

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

4 Associate

Professor, Department of Management, Arka Jain University, Jamshedpur,

Jharkhand, India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fashion Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

6 Associate

Professor, Department of Management, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology,

Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

7 Department

of CSE (AIML), Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

With the fast

adoption of artificial intelligence in the art and cultural industry, the

production, curation, distribution, and management of creative works have

been radically transformed. Intelligent systems that allow artists, curators,

institutions, platforms, and intelligent systems to work together in

continuous interaction are now known as AI-driven art ecosystems. The paper

explores management innovation as it manifests in AI-based art systems, the

changes in managerial practices, forms of governance and decision making, in

reaction to advanced computational creativity and data-driven work. The paper

conceptualizes AI-based art systems as multi-layered systems that include

creative production, curatorial intelligence and digital distribution systems

such as online galleries and non-fungible token-based markets. It emphasizes

the ways in which management innovation is developed in the form of a

workflow redesign that combines automation and human-AI partnership to allow

efficiency without sacrificing artistic intent and cultural sensitivity.

Additionally, the paper focuses on the governance innovations that respond to

the issues of transparency, accountability, ethical compliance, and

authorship attribution in creative settings with algorithms mediating them. The resource orchestration is considered a key managerial

competency with a focus on the strategic alignment of data resources,

innovative talent, and computing resources. The study further examines the

AI-enhanced decision-making in the context of art institutions and how the predictive analytics and the intelligent

recommendation systems can be used in audience engagement prediction,

curatorial planning, and portfolio management. Based on the selected case

studies of AI-integrated museums, hybrid creative studios, and global AI-art

hubs, the paper finds the best practices and benchmarking perspectives. |

|||

|

Received 18 June 2025 Accepted 02 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Mazin

Nawwaf Assi, mazin.assi@zust.edu.ps DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6927 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Driven Art Ecosystems, Management Innovation,

Human–AI Collaboration, Cultural Governance, Creative Industries, Digital Art

Management |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Artificial intelligence (AI) and the arts have begun to converge and bring a tectonic shift in the organization, control, and administration of modern creative systems. Art is no longer limited to the mode of production, display, and patronage but rather, it is becoming functionalized in digitally mediated conditions where algorithms, data infrastructures, and intelligent platforms are actively taking part in the creation of creative value. In this regard, management innovation has been introduced as one of the most vital factors of the capacity of art ecosystems to adapt to AI-driven change and maintain artistic agency, cultural value, and organizational sustainability. The acting ecosystems of AI-driven art systems are so diverse to include, but are not limited to, artists, curators, cultural institutions, technology platforms, audiences, and automated systems that work together to co-create, assess, and distribute artistic works. In the past, art management was concerned with curatorial experience, institutional reputation, and mediation on markets using galleries, museums and cultural organisations Gunter (2022). But with the emergence of generative AI, recommender systems, computer vision and predictive analytics, these traditional structures have been broken. Artistic production is being facilitated by AI systems that can be used to create images, music, text, and other interactive experiences, frequently in models of human-AI co-creation. Meanwhile, data-driven evaluation, sentiment analysis, and audience analytics are expanding the range of curatorial processes, allowing any institution to make better decisions regarding exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming Mazur-Wierzbicka (2021).

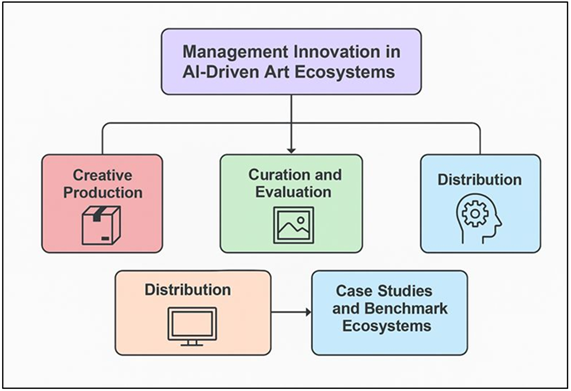

Channels of distribution have also ceased to just be physical space but have expanded to digital platforms and virtual galleries and blockchain enabled market places making the task of managerial control and strategic planning more difficult. Such changes in technology require new types of management innovation that extend beyond optimization of processes. The managers involved in the AI-driven art ecosystems should restructure their workflows to create an equilibrium between automation and human decision-making, so that the efficiency benefits of the work do not compromise the creative abilities and cultural value Cudecka-Purina et al. (2022). It is also necessary that they create governance systems that are responsive to new ethical issues like algorithmic prejudice, author ambiguity, and intellectual property as well cultural consequences of AI-generated content. Figure 1 demonstrates integrated management architecture that facilitates coordinated art ecosystems that are driven by AI. In contrast to totally commercial digital platforms, art ecosystems are under the influence of symbolic, social, and cultural systems of values, so the management decisions are distinctly sensitive and multidimensional.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Integrated Management Architecture for AI-Driven Art Ecosystems

In addition, AI brings in data as one of the focal strategic resources in art management. The data of audience interaction, visual archives, metadata, and behavioral analytics continue to shape the curatorial practices and the plan of the institution. Successful resource coordination is now embodied in the need to align artistic skill, technology, and computer resources in a sensible managerial perspective. This change changes leadership concepts in art institutions, and demands hybrid skills that combine cultural wisdom with data literacy and technological management. The decision-making operations are also changed, predictive models facilitate the forecasting of the content engagement, market trends, and performance of the collection to be more proactive and flexible in their approach to management Herb (2022). In spite of the increased presence of AI in the creative industry, the management innovation of AI-driven art ecosystems is still a relatively unexplored scholarly topic. The current literature tends to concentrate on the technological potential or artisanal outputs, and little is made on the managerial framework, organizational plans, and integration on a systemic scale. This is the main limitation because the art institutions and creative businesses cannot leverage AI in ways that are responsible and sustainable Maury-Ramirez et al. (2022). This threat needs to be addressed in a holistic manner in which AI technologies are placed in the context of wider management, governance, and culture.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of art management practices in digital culture

The art management practices have undergone a significant shift along with the general digitization of cultural production and distribution. The first attempts at managing digital art occurred as people started using rudimentary information systems to manage collections, operate archives, and facilitate the running of administrative functions in museums and galleries. With the growth of digital culture via the internet and social media, the institutions of art started to transition to audience-focused management paradigms and focus on accessibility and engagement, as well as international coverage Mangers et al. (2021). Online exhibition, virtual tours and online archives rethought the ways in which cultural organizations communicated with various audiences, and managers needed to acquire new skills in digital communication, platform coordination and content strategy. This development of platform-based cultural economies further changed the way art management operated through the introduction of data-driven strategies to audience development and market mediation Ahmed et al. (2022). Such indicators as views, shares, and engagement rate had become influential metrics that define curatorial and promotional decisions. The strategic branding, experience design, and cross-sector partnership with technology providers and creative industries started to be used in management practices. It was also a time when hierarchical institutional models were beginning to be replaced by more networked and ecosystem-based models of management, in which artists, curators, technologists, and audiences worked together in order to make cultural values Bhattacharya et al. (2024).

2.2. AI Technologies Influencing Creative Production and Curation

In the recent literature, it is emphasized that there is an increasing role of artificial intelligence technologies in artistic production and curating in the arts. Increasing the creative power of art by making images, music, text, and interactive media generable through algorithmic methods, generative models, such as generative adversarial networks, diffusion models, and transformer-based systems, have extended the original concept of art and art history to new forms and forms of creative production Morandín-Ahuerma (2022). These tools enable human-AI co-creation of content and artists provide direction and refinement in addition to contextualising an output of a given algorithm instead of just consuming automated content. Studies underline that through such systems, creative processes change to include experimentative, rapid prototyping, and new aesthetic opportunities that pose a challenge to conventional authorship and originality notions. Simultaneously, AI technologies have been changing the curatorial practice with the help of automated classification, recommendation, and evaluation systems Manish et al. (2022). The methods of computer vision and natural language processing make it possible to analyze visual and textual art data on a large scale and facilitate a variety of tasks, including style recognition, thematic clustering, and sentiment analysis of audience reaction. The use of recommendation engines in exhibition design and digital collections, as well as online art marketplaces, is becoming more widespread, as artificial intelligence personalizes the content to different people.

2.3. Gaps in Current Research on AI-Enabled Art Ecosystems

Although the research on the topic of AI applications in the arts has become increasingly popular in scholarly literature, there are still many gaps in the examination of AI-assisted art ecosystems in the aspects of management and organization. The available literature is mostly devoted to the technical abilities of AI models or philosophical arguments around the issue of creativity, authorship, and aesthetics. In as much as these contributions are important, they tend to ignore the operationalization of AI technologies, how they are governed, and how they are integrated strategically in multifaceted art ecosystems with numerous stakeholders Verma and Verma (2022). Therefore, less focus is given to managerial decision making, coordination of workflow and institutional adjustment in cultural environments mediated by AI. The other gap is the disjointed treatment of the dynamics of the ecosystem. Research often looks at single examples of uses like AI generated art or algorithmic curation in digital platforms and does not think about how artists, institutions, platforms, markets and audience interact. This overly specific approach limits knowledge of the relationship between AI-driven art systems and value co-creation, distribution, and regulation Fang et al. (2023). Table 1 is an overview of management innovation studies on AI based art ecosystems. In addition, there is limited empirical research and especially comparative studies on management innovation in art institutions, including an evaluation of alternative governance schemes, resource strategies, and organizational results. There is also a lack of incorporation of ethical and cultural dimensions in analysis centered on management.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work on Management Innovation in AI-Driven Art Ecosystems |

||||

|

Focus Area |

AI Technologies Used |

Management Perspective |

Application Context |

Limitations |

|

Cultural analytics |

ML, data mining |

Data-driven cultural

management |

Digital art platforms |

Limited managerial depth |

|

Platformized culture |

Recommender systems |

Platform governance |

Online galleries |

Artist agency underexplored |

|

AI creativity Fang et al. (2023) |

GANs |

Creative process management |

AI-generated art |

Ethical issues not addressed |

|

Creative economy |

Predictive analytics |

Strategic management |

Cultural institutions |

Focused on economics |

|

Digital curation Saptaputra and Bonafix (2023) |

Computer vision |

Curatorial innovation |

Museums |

Human oversight limited |

|

AI ethics |

XAI frameworks |

Ethical governance |

Cross-sector |

Not art-specific |

|

Art markets |

Algorithms |

Market mediation |

Art platforms |

Limited AI technical detail |

|

Museum analytics |

Data analytics |

Audience management |

Museums |

Small-scale studies |

|

Cultural bias in AI Das and Mondal (2023) |

NLP, CV |

Inclusive governance |

Heritage datasets |

Lacks management solutions |

|

Digital transformation |

AI, IoT |

Organizational change |

Cultural organizations |

Generic framework |

|

NFTs and art |

Blockchain, AI |

Value chain management |

NFT marketplaces |

Volatile market focus |

|

Recommendation systems Feng et al. (2022) |

Deep learning |

Decision support |

Online art platforms |

Cultural diversity ignored |

|

Creative labor |

Automation |

Workforce management |

Creative industries |

Pre-AI art focus |

|

Ecosystem innovation |

AI-driven platforms |

Ecosystem orchestration |

Cross-industry |

Not art-specific |

3. Architecture of AI-Driven Art Ecosystems

3.1. Creative production layer: generative AI, co-creation tools

The creative production layer is the primordial ingredient to AI-based art ecosystems because artistic ideation and implementation are progressively aided by artificially intelligent systems. Such generative AI systems as diffusion models, generative adversarial networks, and transformer-based systems can generate visual, auditory, and textual content using a wide range of inputs (prompts, sketches, datasets, and stylistic references). They have helped to expand the limits of art through providing artists with quick experimentation of form, color, composition, and narrative framework, without limited to traditional material or media Lv (2023). Instead of substituting human creativity, modern literature is focused on the co-creation paradigms where a creative person retains the right to control the idea, and AI acts as an adaptive partner. Co-creation tools combine prompt engineering interface, real-time refinement and iterative feedback interface and place AI into the creative process. These systems promote a versioning, stylistic modulation and context conditioning where artists can align outputs to either a cultural, historic or a personal aesthetic preference. On the management side, this layer must be orchestrated with care involving creative autonomy, technical infrastructure, and intellectual property issues. To practice creativity in a responsible way, institutions will have to formulate policies regarding the use of data, the attribution of authorship, and the limits of ethics.

3.2. Curation, Evaluation, and Recommendation Engines

Using computer vision, natural language processing, and multimodal embedding models on a particular work of art, contextual metadata, and interaction with the audience on a large scale, this layer is used to analyze works of art. The automated classification systems recognize patterns of style, relationships of theme and reference to history helping curators to sort out large and heterogeneous collections. Judgment engines also examine attributes of art, viewer feeling and interaction rates, which allow informed decisions based on data, which can enhance expert curatorial judgment. Recommendation systems are also central in the audience experience on both the digital and physical platforms. These systems customize exhibition routes, web collections and market presence using the data of behavior of users and the similarity of content. As a management point of view, these engines are beneficial to make decisions more efficiently and aligning them with the audience, however, they also carry a threat of cultural homogenization and algorithmic bias. This means that model design and human supervision must be transparent so as to maintain the diversity of curators and critical interpretation. Another area where this layer helps in planning strategies in art institutions is in strategic planning. Thematic exhibitions can be predicted in terms of attendance and trends in engagement, as well as their reception, and predictive analytics can be used to allocate resources proactively and streamline programs.

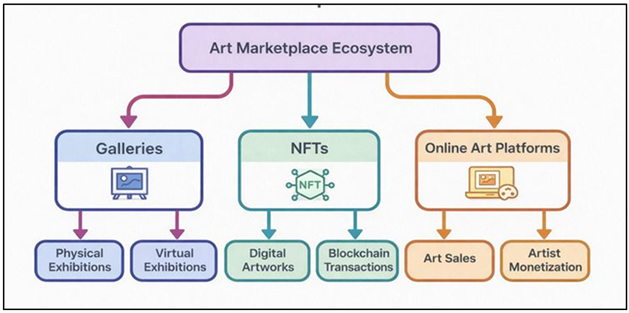

3.3. Distribution and Marketplace Infrastructures: Galleries, NFTs, Platforms

The distribution and marketplace layer is the externally visible face of AI driven art ecosystems in terms of how the art is put out into the world by linking creative production and curation with audiences, collectors and markets. This layer includes physical galleries enhanced by digital technologies, web platforms, virtual exhibitions, and electronic markets based on blockchain technology, including the non-fungible token ecosystem. Figure 2 presents the workflow in AI-driven art ecosystems in distribution and marketplace infrastructure. These infrastructures are supported by AIs, which assist in automated prices modelling, demand prediction, audience analysis, and customized content delivery, which allows reaching a wider audience and more effectively interacting with the market.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Flowchart of Distribution and Marketplace

Infrastructure in AI-Driven Art Ecosystems

Digital platforms reinvent the historic gatekeeping through their ability to enable artists to directly distribute and monetize their work, and generally have visibility and discovery mediated by algorithm. Specifically, the NFT markets, particularly, bring programmable ownership, provenance, and smart contracts and transform the value exchange and intellectual property management. In terms of management innovation, new strategic capabilities in the areas of platform governance, revenue models, and risk management are needed by these infrastructures. The institutions have to deal with the regulatory uncertainty, environmental issues, and market uncertainty and simultaneously have to be transparent and trustworthy.

4. Management Innovation Dimensions

4.1. Workflow redesign: automation, augmentation, human–AI collaboration

Workflow redesign is one of the primary aspects of management innovation in AI-based art systems, as through creative, curatorial, and administrative processes reorganized around smart technologies institutions redesign and restructure their operations. Repetitive and time-consuming tasks, including metadata creation, tagging content, organizing archives and simple audience analytics, can be managed with automation and enhance operational efficiency to a large degree. Nonetheless, when applied to creative industries, automation cannot be solely applied and might be counterproductive in case it excludes human opinion and artistic control. As a result, modern management trends are focused on augmentation, in which AI systems complement human abilities but do not substitute them. The models of human-AI collaboration reorganize the workflow with the purpose of facilitating the iterative process of interaction between artists, curators, and algorithms. Artificial intelligence helps in ideation, generation of variations and technical implementation in creative production, and conceptual intent, cultural context, and critical evaluation are offered by humans. Algorithms are used in curatorial processes, yet not in making decisions on what to select and interpret. Managers are important in the development of collaborative interfaces, decision limits, and creation of organizational cultures that promote experimentation and critical interactions with AI outputs.

4.2. Governance Models: Transparency, Accountability, Ethical Protocols

To address social, cultural and ethical impacts of AI based art ecosystems, governance innovation is needed. With the growing role of the algorithmic systems in creative production, curation, and distribution, institutions should develop governance models that will prove transparency and accountability in the decision-making processes. Transparency means making AI systems readable to the stakeholders by writing down the data sources, model logic and the evaluation criteria, which makes algorithmic mediation less opaque. In creative practices, clear governance will contribute to trust and knowledgeable engagement of artists and audiences in creative settings that are enabled by artificial intelligence. Accountability systems characterize accountability on outcome generated by human-AI cooperation. These involve explaining authorship attribution, intellectual property rights and responsibility of biased and harmful outputs. Ethical guidelines also inform the responsible use of AI by involving the topics of misrepresentation of cultures, marginalization, and exploitation of heritage information. In the management light, governance systems should incorporate ethical scrutiny systems, cross-disciplinary governance committees and adherence to the law and policy requirements.

4.3. Resource Orchestration: Data, Talent, Computational Assets

Resource orchestration is a new innovation in the strategic management of AI-driven art ecosystems where value creation relies on the orchestration of various and interdependent resources. Information has become an internal resource, including a collection of digital data, a record of interactions with the audience, footprints of creative processes, and contextual data. To be well governed, data needs to be both accumulated and governed responsibly to ensure quality control and contextual annotation in the process of maintaining cultural meaning and preventing reductive analytics. The choices of sharing data, right of access and stewardship have a direct impact on the credibility and ethical reputation of the institution. The orchestration of talents is also important since AI-based art ecosystems require hybrid expertise between artistic abilities, curatorial and technical skills. The managers need to create cross-functional teams in which artists, data scientists, designers, and cultural managers will work together. This usually employs the redefining of organizational functions, the promotion of cross-functional education, and the provision of creative freedom and technical strictness. Talent development plans can therefore become part of the innovation sustenance strategies.

5. AI-Enhanced Decision-Making in Art Institutions

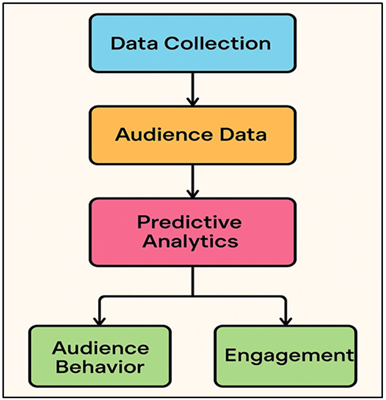

5.1. Predictive analytics for audience behavior and engagement

Predictive analytics is now a game changer in the decision making process of art organisations allowing managers to predict the behaviour of audiences and create more receptive cultural experiences. Through historical records of attendance, demographics, data on the digital interactions, and social media indicators, AI models can propose future visitor trends, the intensity of engagement, and preferences among the crowds in terms of time and platforms. These insights can inform strategic choices within the areas of exhibition scheduling, marketing campaigns and resource allocation that help to create less uncertainty in a highly competitive cultural environment. The audience behavior and engagement modeling in predictive analytics is demonstrated in the Figure 3. Time-series forecasting and clustering algorithms are some of the machine learning methods that enable institutions to recognize individual groups of audiences and forecast their behavior patterns.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Flowchart of Predictive Analytics for Audience Behavior and Engagement

This makes it possible to offer individualized communication plans, outreach, and responsive programming that can cater to the interests of the audience and increase inclusivity. Regarding management, predictive analytics transform the decisions into a reactive mode of decision-making rather than a proactive one that enables institutions to tailor and optimize their staffing efforts, price sets, and accessibility programs. Nonetheless, managerial and ethical issues are also caused by the dependence on predictive models. Excessive focus on popularity metrics that rely on data might favor major groups of audiences and disregard experimental or culturally important practices. Hence, to make quality decisions, one should amalgamate both forecasting understandings and curatorial discretion and institutional objective. Managers should have the transparency of model assumptions and assess the social impact of analytics-based strategies on a regular basis. When applied in a responsible manner, predictive analytics strengthens the audience engagement at the same time as it does not harm the cultural, educational, and serving functions of art institutions within the AI-based ecosystems.

6. Data-Driven Curatorial Planning and Exhibit Optimization

Artificial intelligence-based data analytics continues to shape the planning of curation and exhibition design, which is used in art institutions to make evidence-based decisions. Combining visitor movement tracking, feedback surveys, and digital interactions, as well as content analytics, AI systems can give insights into the way the audience can engage with artworks and exhibition spaces. Those lessons allow curators and managers to evaluate the logicality of narrative integrity, spatial continuity, and thematic resonance, and allow optimizing exhibition layouts and interpreting resources in an iterative way. Strategic curatorial planning is also supported by data approaches that determine emerging trends, underrepresented themes, and cross-cultural relationships in a collection. The tools of natural language processing and computer vision can be used to explore the big archive to demonstrate thematic patterns and stylistic affinities that might not be clear without a manual search. Management wise, this promotes efficiency of curators and helps in long-term program proposals in line with the objectives of the institutions and audience development. However, the process of curatorial decision-making is subjective and interpretive in nature. Excessive use of quantitative indicators may make exhibitions to transform into performance measurements instead of cultural narratives. Good management innovation thus makes AI a decision-support, and not a decision-maker. Human curators put insights derived by data into historical, social, and ethical frameworks thus ensuring that any exhibition is intellectually sound and culturally significant. AI-enhanced planning supports the flexibility of institutions without interfering with artistic quality because the analytical optimization is balanced with the curatorial judgment.

6.1. Intelligent Portfolio and Collection Management

The use of AI in art institutions through intelligent portfolio and collection management is a strategic approach where the management can have more systematic stewardship of cultural assets. It is an artificial intelligence system that uses the records of acquisition, conservation, market data, and audience performance to aid in making decisions about collection development, loan policies, and deaccessioning. Long term cultural and economic value can be evaluated using predictive models to ensure that managers adopt collection strategies that are aligned with institutional missions and sustainability objectives. Data mining and computer vision allows analyzing collections on a large scale and finding gaps in style, redundancies, and diversification opportunities. This assists in broader and more representative acquisition policies, which deals with historical biases in acquiring practices. Intelligent portfolio tools, in terms of their management, can increase the transparency and accountability of the high stakes decisions when they involve the public trust and cultural heritage as a structured evidence can be presented. Simultaneously, there are ethical obligations that collection management is beyond the optimization. Algorithms cannot capture cultural importance, provenience, and community connections, which are the primary aspects of the cultural heritage. To ensure the success of AI adoption in business, managers should hence incorporate AI knowledge in governance models that focus on curatorial ethics and consultation with stakeholders. Intelligent portfolio management enhances risk management, long-term resiliency, and resource planning when well utilized. AI-enhanced collection management helps to make sustainable decisions in the developing art ecosystem through the combination of analytical rigor and cultural stewardship.

7. Case Studies and Benchmark Ecosystems

7.1. AI-integrated museums and digital galleries

Intelligent museums and online galleries are the first steps towards the future of using intelligent technologies in managing cultural organizations and their innovation. The major museums have embraced the use of AI to digitize their collections, identify the artifacts according to a computer, and offer visitors more opportunities, including tailored suggestions and interactive exhibits. Computer vision applications aid in the analysis of artworks, condition assessment, and organization of archives and allow institutions to become more efficient in terms of conservation and documentation. The digital galleries also add to these features and provide virtual exhibitions, real-life experience, and data narrative that are not limited by geographical boundaries. On the managerial level, these institutions show how the integration of AI necessitates restructuring of the organization, cross-disciplinary work, and new governance practices. Effective museums have set up digital innovation units that work closely with curators, technologists and educators so that the technology experimentation is coordinated to the mission of the institution. The exhibition planning and outreach to the audience are informed by AI insights, whereas the interpretation and cultural sensibility are ensured by a human presence. Best practices in transparency, ethical application of AI, and stakeholders engagement are seen through benchmarking such institutions. It is important to note that AI-enhanced museums tend to employ gradual implementation processes, which piloting technologies, and then proceed with a large scale implementation to handle risk and develop internal capacity.

7.2. Creative Studios Using Hybrid Human–AI Design Pipelines

Examples of novel production models in AI-driven art ecosystems include the use of creative studios that apply hybrid human-AI design pipelines to their production process. These studios use generative AI systems in artistic processes, assisting ideation, prototyping and refinement of artistic processes in fields like visual art, design, animation and music. This co-operative model does not replace creative authorship, but increases productivity. Such studios focus on management practices that highlight flexibility in the workflow, cross-disciplinary teams, and unceasing experimentation. In order to be AI-literate, leaders invest in training artists and designers to be able to use generative tools and analyze their results. The intellectual property policies are frequently redefined so as to meet the co-created works, data provenance and licensing terms. Agile project management techniques can also be seen through these studios as the product is designed through fast iteration and feedback loops instead of linear production pipelines. Benchmarking hybrid studios places an emphasis on how organizational culture is vital in the continuation of innovation. Effective studios maintain an atmosphere of openness to experimentation and do not compromise on ethical guidelines and standards of quality. They are commercial but at the same time they are creatively exploring and AI is an allowing factor and not a defining factor of artistic value. Hybrid human-AI studios as case studies are examples of how management innovation can match the technology ability with visionary creativity and provide scalable example of the artistic production into the future.

7.3. Comparative Analysis of Global AI-Art Innovation Hubs

The existence of AI-art in the global ecosystems through hubs offers insightful comparative information on how ecosystems in various regions influence the assimilation of AI and art. These centers are usually situated in urban centers with high technology, and include cultural facilities, artisan industries, research institutions and technology start-ups in tight networks of collaborative co-location. The differences in policy-making structures, financing schemes, and cultural concerns determine the way AI-driven art ecosystems develop and are operated. In comparative analysis, it can be seen that there are varied management and governance styles in the regions. Others focus more on leadership within the public sector: museums and cultural agencies are leading the challenge to adopt AI due to research collaborations and governmental funding. Others are described as platform-based innovation whereby private technology companies and innovative startups are in charge of ecosystem coordination. There are also some discrepancies related to the ethical governance where some of the hubs place more emphasis on cultural preservation and inclusiveness and others are more attuned to market scalability and global visibility. The benchmarking by hub is used to identify the key success factors of hubs which include collaboration across sectors, favourable policy conditions, and investment in education and talent development. Hubs which incorporate cultural values into the technological strategy are more likely to have more sustainable and socially legitimate results.

8. Conclusion

The development of AI-driven art ecosystems is a massive change in the way a new value in art is produced, handled, and maintained in the digital world. This paper has established that the key to getting through this change is to focus on management innovation since AI technologies are transforming creative production, curation, distribution, and institutional decision-making. Instead of acting as standalone tools, AI systems are the parts of the multidimensional socio-technical ecosystems, which require adaptive managerial approaches, ethical control, and interdisciplinary teamwork. Using the lens of AI-driven art ecosystems as layered architecture, the paper identifies management innovation as a concept that is created through workflow redesign, governance development, and strategic resource orchestration. Human-AI collaboration becomes one of the main principles that allow institutions to use automation and analytics without losing an artistic purpose, cultural values, and curatorial knowledge. The governance models that are oriented in terms of transparency, accountability, and ethical guidelines are proven to play a crucial role in dealing with the issue of authorship, bias, privacy of data, and intellectual property. The concept of AI-based decision-making can be analyzed to depict that predictive analytics and smart management tools facilitate more active and evidence-based institutional strategies. When combined thoughtfully, these tools are beneficial to increase audience interaction, curatorial strategy and collection management without scaling art to only measurable quantitative standards. Case studies and benchmark ecosystems also prove that the successful implementation of AI does not rely on a high level of technology, but on a leader vision, organizational culture, and cultural value alignment.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. A., Nazzal, M. A., Darras, B. M., and Deiab, I. M. (2022). A Comprehensive Multi-Level Circular Economy Assessment Framework. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 32, 700–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2022.05.025

Bhattacharya, S., Govindan, K., Dastidar, S. G., and Sharma, P. (2024). Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Closed-Loop Supply Chains: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 184, 103455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2024.103455

Cudecka-Purina, N., Atstaja, D., Koval, V., Purvins, M., Nesenenko, P., and Tkach, O. (2022). Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals Through the Implementation of Circular Economy and Developing Regional Cooperation. Energies, 15, 4072. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15114072

Das, M., and Mondal, S. (2023). IoT Enable Intelligent Smart Bin for Garbage Monitoring Based on Real-Time Data Analysis. International Journal of Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, 11, 1014–1018. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2023.53746

Fang, B., Yu, J., Chen, Z., Osman, A. I., Farghali, M., Ihara, I., Hamza, E. H., Rooney, D. W., and Yap, P. S. (2023). Artificial Intelligence for Waste Management in Smart Cities: A Review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 21, 1959–1989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01604-3

Feng, Z., Yang, J. C. H., Chen, L., Chen, Z., and Li, L. (2022). An Intelligent Waste-Sorting and Recycling Device Based on Improved EfficientNet. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 15987. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315987

Gunter, S. (2022). Circular Economy: Illusion or First Step Towards a Sustainable Economy: A Physico-Economic Perspective. Sustainability, 14, 4778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084778

Herb, B. (2022). Building a Circular Economy. Visual Education, 311, S1. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03643-2

Lv, Z. (2023). Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Metaverse Era. Cognitive Robotics, 3, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogr.2023.06.001

Mangers, J., Minoufekr, M., Plapper, P., and Vijay Keshav Kolla, S. S. (2021). An Innovative Strategy Allowing a Holistic System Change Towards Circular Economy Within Supply-Chains. Energies, 14, 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144375

Manish, A., Bilal, W., and Haju, S. (2022). Artificial Intelligence. International Journal of Science, Technology and Engineering, 10, 1210–1220. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2022.44306

Maury-Ramirez, A., Illera-Perozo, D., and Mesa, J. (2022). Circular Economy in the Construction Sector: A Case Study of Santiago de Cali (Colombia). Sustainability, 14, 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031923

Mazur-Wierzbicka, E. (2021). Circular Economy: Advancement of European Union Countries. Environmental Sciences Europe, 33, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00549-0

Morandín-Ahuerma, F. (2022). What Is Artificial Intelligence? International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 3, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.55248/gengpi.2022.31261

Saptaputra, E. H., and Bonafix, N. (2023). Mobile App as Digitalisation of Waste Sorting Management. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1169, 012007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1169/1/012007

Verma, A., and Verma, H. (2022). A Review of Artificial Intelligence and Its Application in the Future Medical Field. International Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management, 6, 1–7.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.