ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Augmented Reality and AI in Public Art Management

Riyan Sisiawan Putra 1![]()

![]() ,

Bhanu Juneja 2

,

Bhanu Juneja 2![]()

![]() ,

Hanna Kumari 3

,

Hanna Kumari 3![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Naresh Kaushik 4

,

Dr. Naresh Kaushik 4![]()

![]() ,

Rajat Kumar Dwibedi 5

,

Rajat Kumar Dwibedi 5![]()

![]() ,

Kalpana Rawat 6

,

Kalpana Rawat 6![]() , Shrikant Shrimant Barkade 7

, Shrikant Shrimant Barkade 7![]()

1 Department

of Management, Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Surabaya, Indonesia

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Interior Design, Parul Institute of

Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

4 Assistant Professor, UGDX School of Technology, ATLAS Skill Tech

University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

5 Assistant Professor, Gr. II, Department of Electronics and

Communication Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka

Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

6 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida

International University, India

7 Department of Chemical Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Public art

management is becoming increasingly challenged by the swift urbanization,

disjointed governance, a lack of interaction with the audience, and a

requirement to make data-driven decisions. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and

Augmented Reality (AR) have the potential to revolutionize the way people

visualize, plan, and monitor and experience public artworks. In this paper,

the author suggests an AR-AI framework of managing the public art that

involves the fusion of immersive spatial visualization, intelligent

analytics, and another aspect of automation. Based on the idea of the public

art management theory, urban cultural policy, and digital placemaking, the

framework allows simulating artwork placement in the actual situation in

urban environments, evaluating the site appropriateness with the help of

machine learning, and tracking the state of the artwork with the help of

computer vision analysis. The natural language processing modules can also

assist participatory governance by helping to extract sentiment, theme, and

concerns of public feedback in various digital platforms. The proposed system

will combine heterogeneous data sources such as geospatial data,

environmental factors, engagement by the audience and cultural metadata to

provide evidence-based decision-making at every stage of the artwork

lifecycle. In addition to the efficiency in operations, AR-based storytelling

and pedagogical overlay contribute to the cultural interpretation, access,

and civic participation. Ethical issues, such as privacy in surveilled public

places, bias in cultural algorithms, and sustainability of technologies in

the long-term, are also critically assessed in the study. |

|||

|

Received 17 June 2025 Accepted 01 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Riyan

Sisiawan Putra, riyan_sisiawan@unusa.ac.id

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6924 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Augmented Reality, Artificial Intelligence, Public

Art Management, Smart Cities, Urban Cultural Policy, Digital Placemaking |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

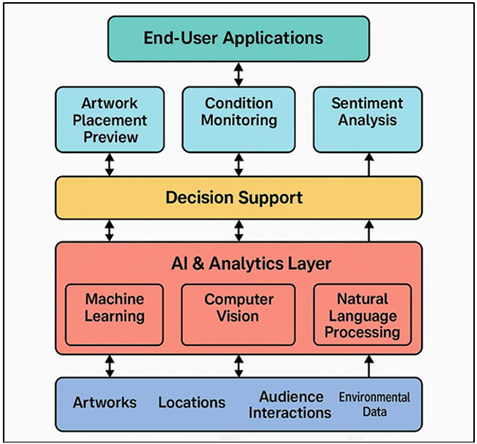

The public art has been a very important form of cultural expression, civic discourse, and collective memory in urban space. Murals, sculptorse, exhibitions and performance art pieces influence the visual identity of urban areas as well as mirror social values, historical accounts, and societal hopes. Nevertheless, the process of managing public art in urban centers has gotten to be more complicated because of high urbanization, space and time limits, various stakeholders interest as well as the changing demands of interaction with the population. Conventional methods of management of traditional public art, with a tendency of manual planning, expert judgment and fixed documentation, finds it difficult to respond to issues of site suitability, long-term maintenance, audience involvement, and transparent decision making. In its part, the emerging digital technologies present the new possibilities to reconsider the way in which public art should be designed, how it is governed, experienced, and sustained Busaada and Elshater (2021). The concepts of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Augmented Reality (AR) have been greatly discussed in the smart city projects, cultural heritage preservation, and urban management because they are capable of merging both physical and virtual space via information-focused intelligence. AR facilitates the superimposition of virtual over real-life environments which means that stakeholders can see the artworks in place prior to installations, interactively interpret the cultural meanings of objects, and perceive the overlay of narratives within the city. Parallel to this, AI represents effective computational applications to process big data of heterogeneous data, to assist predictive decision-making, automation, and adaptive management Nia and Olugbenga (2020). The architecture of AI-based multilayer in Figure 1 allows intelligent management of public art. AR and AI create a complementary technological ecosystem that, when combined, can revolutionize the idea of public art management as a stagnant and reactive practice into an active, dynamic, and evidence-based practice.

Figure 1

Figure 1 AI-Driven Multilayer Architecture for Intelligent

Public Art Management

The process of introducing AR and AI in the management of public art is in line with the larger changes to data-driven urban cultural policy and participative governance. Cities are growing more interested in the ways to reconcile artistic freedom and inclusiveness, sustainability and responsibility to the varied publics. Machine learning will help planners and curators to discover the best places to place artworks by evaluating spatial, environmental, and socio-cultural factors, and computer vision will allow tracking the state of artwork, its deterioration, and the risk of vandalism. NLP is also useful in democratic participation, as it isolates the information on the common reaction to it in the form of feedback, discourse on social media, and community consultation Cheng et al. (2023). These capabilities enable cultural authorities to cease focusing on a single-installation choice to a lifecycle-oriented management approach that can change with the current urban environments. AR helps in improving public access to art at the experiential level by providing immersive storytelling, multilingual interpretation, and educational overlay allowing the contextualization of artwork through historical, social, and environmental contexts. These experiences have the potential to enhance greater emotional bonding, education, and cultural sensitivity among the audiences who would have otherwise not been interested in traditional forms of public art. Notably, the data collected during the AR-mediated interactions also creates valuable information about the audience, their behavior and preferences, which are provided as a feedback to the AI-oriented analytics to further improve the cultural interventions Wang (2022). In spite of its capabilities, AR and AI implementation in the management of public art provokes serious ethical, social, and practical issues. The problem of data privacy, surveillance in open areas, algorithmic bias, and technological obsolescence should be addressed carefully to promote the responsible and fair implementation. The paper frames these technologies in existing theories of art management in the public and urban cultural policy that characterizes an integrated AR-AI strategy that informs inclusive decision-making, cultural sustainability, and meaningful public involvement in the contemporary urban environment Matthews and Gadaloff (2022).

2. Conceptual Foundations and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Public art management theories and urban cultural policy

Interdisciplinary theories of cultural policy, urban studies, arts administration and public governance form the basis of public art management. Conventionally, the meaning of public art has been interpreted as a civic good, which helps in placemaking, social cohesion, and cultural identity. Management theories also focus on the lifecycle of artistic works in a public, such as commissioning, site choice, stakeholder consultation, installation, conservation, and maintenance in the long run Nikoo and Sajjadzadeh (2018). Some of the models, including participatory cultural governance, have emphasized community, artists, planners and policymakers as co-creators of public art as opposed to mere recipients. This change is indicative of the wider democratic principles in urban cultural policy in which inclusiveness, openness and societal influence are given greater emphasis than aesthetic worth. Increasingly, the cultural policy frameworks in urban areas are putting public art as a key tool towards urban regeneration, tourism and sustainable development Young and Marshall, M (2023). Creative cities, cultural ecosystems, place-based cultural planning, and other concepts require evidence-based decision-making and intersector partnership. Nonetheless, the traditional management strategies tend to be based on qualitative assessment, scanty records, and disjointed information, and it is hard to evaluate the effect in the long-term, fairness and sustainability. Due to the increased complexity and the cultural diversity of cities, the management of public art needs to be adjusted to the changing conditions of space, social, and environmental settings Sovhyra (2022).

2.2. Augmented Reality as a Medium for Spatial Storytelling and Visualization

Augmented Reality (AR) has become an effective device used to improve spatial awareness and digital storytelling in the real world. In contrast to virtual reality, where the users are transported into an entirely simulated environment, AR superimposes computer-generated content on the real conditions of the urban spaces, leaving the material aspects of the urban environments intact but adding a set of new meanings. Within the field of public art, AR is also used as a spatial narrative device, allowing artworks to be viewed, labelled, and perceived more than just through their physical presence Wang and Lin (2023). The ability can make any stationary installation dynamic and cultural interface, which develops over time. Theoretically, AR shares similarities with locative media, digital placemaking and embodied interaction. These frameworks focus on meaning and its construction in movement, context and contribution of the users to the space. AR visualization gives planners and artists the opportunity to visualize artwork at scale, evaluate their visual compatibility with the surrounding architecture, and experiment with other design possibilities before the physical installation Al-Kfairy et al. (2024). To the viewers, AR can be used to provide interactive storytelling, recreations of historical events, and contextual clarification to enhance meaning and reach.

2.3. Artificial Intelligence for Decision Support, Analytics, and Automation

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is viewed as the analytical foundation of data-driven management of public art, as it allows making decisions based on more data, performing predictive analytics, and automating business processes. Theoretical backgrounds of AI in this area have their roots in the fields of decision science, urban analytics, and intelligent systems, where algorithms can help human professionals to find their way in complexity and uncertainty. The public art ecosystems produce heterogeneous data, which can be geospatial, environmental, audience interactions, maintenance history, and the discussion of the population Alkhwaldi (2024). Artificial intelligence methods are quite apt to fuse and derive insights out of such multidimensional datasets. The strategic decision-making is aided by machine learning models as they detect patterns and correlations that are not easily visible to the human eye. In a certain instance, predictive models can be used to assess the considerable suitability of sites on the basis of foot traffic, environmental exposure, socio-cultural indicators, and urban accessibility. Computer vision allows automated tracking of the artwork health, identification of surface damage or fading or vandalism by analyzing the images Uriarte-Portillo et al. (2022). Table 1 outlines AR and AI applications in the management of art in the public. NLP enables the processing of large quantities of consumer response to be analyzed, offering cultural authorities with the opportunity to measure sentiment, themes, and inclusiveness of digital social media. As well as analytics, AI brings automation to the daily management, which increases productivity and scalability.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on Augmented Reality and AI in Public Art Management |

|||

|

Domain |

Data Type Used |

Key Objective |

Methodology |

|

Urban AR Systems |

Geospatial, Visual |

Spatial visualization |

AR overlays, GIS integration |

|

Digital Cultural Analytics |

Cultural metadata |

Cultural pattern analysis |

Computational cultural

analysis |

|

Museum and Public Art |

Visual, Textual |

Visitor engagement |

Interactive AR storytelling |

|

Smart Cities Salar et al.

(2020) |

Urban sensor data |

Urban decision support |

Predictive urban analytics |

|

Immersive Heritage |

Heritage media |

Heritage interpretation |

Immersive visualization |

|

Computational Creativity Gong et al. (2022) |

Artistic datasets |

Creativity modeling |

Generative algorithms |

|

Urban Analytics |

GIS, mobility data |

Site suitability |

Spatial ML models |

|

Cultural Heritage |

Visual, Spatial |

Public education |

Mobile AR applications |

|

Visual Monitoring |

Image data |

Damage detection |

CNN-based analysis |

|

Smart Governance |

Textual feedback |

Public sentiment analysis |

Topic modeling, sentiment

analysis |

|

Experience Economy |

User interaction data |

Experiential engagement |

Immersive experience design |

|

Public Art Policy Sylaiou et al. (2024) |

Policy documents |

Transparent governance |

Digital dashboards |

|

Urban Visualization |

3D city models |

Urban simulation |

AR-based simulation |

|

Public Art Ecosystems |

Multimodal data |

Integrated management |

Hybrid AR–AI frameworks |

3. Proposed AR–AI Framework for Public Art Management

3.1. Overall system architecture and workflow

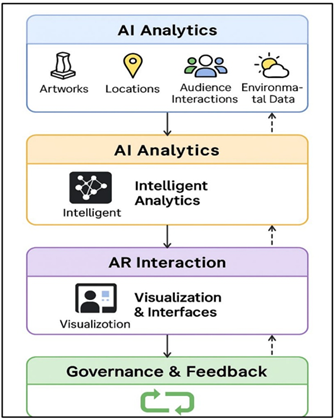

The AR-AI structure of managing the public art is created to be a modular and layered architecture that will be able to incorporate data ingestion, smart analytics, immersion visualization, and interaction with stakeholders in one workflow. The central point of the system is a centralized data and intelligence hub that ties both the physical urban environment and the digital decision support system. The process starts by collecting constantly flowing data through various sources, which is then processed and analyzed using AI models to produce actionable information to the planners, curators, and policymakers. AR–AI system architecture and workflow in managing public art are displayed in Figure 2. These observations are then converted to intuitive AR-based visualization and interfaces to both the professionals and the general population.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Proposed AR–AI System Architecture and Workflow for

Public Art Management

The architecture will consist of 4 main layers, which include the data acquisition layer, AI analytics layer, the AR interaction layer, and the governance and feedback layer. Information is passed upwards through the physical and digital environments to analytics layer where machine learning, computer vision and natural language processing models run. The results of these models are used in decisions regarding the placement of artwork, conservation, and the engagement with the audience.

3.2. Data Acquisition: Artworks, Locations, Audience Interactions, Environmental Data

The proposed AR-AI framework is based on data acquisition; this enables informed adaptable management of public arts by having a complete situational awareness. The system incorporates the heterogeneous data streams which capture the artistic, spatial, social, and environmental aspects of the art ecosystems in the public. Artwork related information comprises digital models, material specification, historical context, intent of the artist, conservation history, and metadata of the lifecycle. The datasets are useful in the curatorial decision-making, and long-term preservation planning. The geographic information systems (GIS) such as spatial coordinates, land-use trends, foot traffic movement, accessibility indicators, and distance to cultural sites are used to capture location data. This kind of data allows the analysis of the suitability of the site and situates the artwork into a context of its city environment. The data on audience interaction is gathered in terms of AR application use, sensors, and voluntary digital interactions and includes such metrics as the frequency of visitation, dwell time, navigation patterns, and preferences of interaction. This information gives an insight into the engagement of the people, inclusivity, and experience. Weather conditions, air quality, light exposure, and urban microclimates are all combined to determine risks in degradation of materials and maintenance schedule.

3.3. AR Layer for Visualization, Annotation, and Immersive Engagement

The AR layer serves as the experiential and communicative platform of the proposed framework and transforms intricate information and analytic outputs into spatial-grounded and intuitive interfaces. Users are able to see proposed or existing works of art within a real urban space at actual scale and point of view by using mobile devices, tablets or AR glasses. This feature allows the planners and artists to preview installations, test visual harmony, and experiment with other scenarios in design before physical installation. In addition to visualization, the AR layer allows annotation of the context with the introduction of digital labels, multimedia content, and interpretive narratives into the real physical location. Interactive overlays allow the audiences to obtain information on artistic ideas, historical allusions, cultural symbols and manufacturing procedures. Educational modules and heritage narratives also enhance the knowledge of the general public, and art is made available to varied groups of the population by means of multilingual and adaptable interfaces. Interactive storytelling features, which include visitor-based AR tours, immersive experiences, location-aware experiences, which react to the movement and behavior of the user, are used to increase the level of immersion. Such interactions enhance higher emotional affiliation and prolonged interest in the artworks of the masses.

4. AI Techniques for Public Art Decision-Making

4.1. Machine learning for artwork placement and site suitability analysis

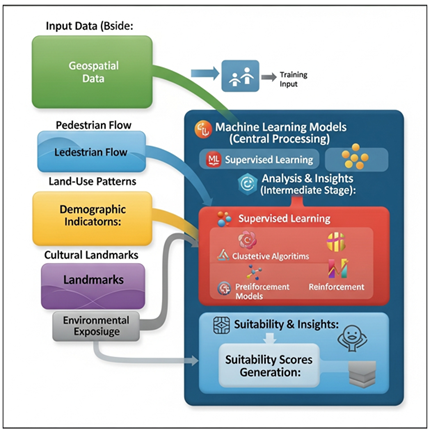

Machine learning is essential in influencing strategic decisions in terms of the location and proper placement of artwork in a complex urban setting. The traditional methods of placing a public artwork include a combination of professional judgments, visual intuition, and small scale site investigations and can miss nuanced spatial, social and environmental relationships. Machine learning models can resolve these shortcomings, which require large, multidimensional datasets of data to find the most suitable locations that balance their artistic will, accessibility to people, and functional city use. Supervised and unsupervised methods of learning are able to incorporate geospatial information, pedestrian traffic, land-use, demographic variables, cultural sites, and environmental exposure to create the suitability scores of potential locations. The clustering algorithms can be used to determine the areas of the city that have similar socio-cultural features and then allocate the public art in the neighborhoods in an equal manner. Predictive models determine the effect of factors like visibility, the number of individuals in a crowd, and the environmental stressors on the audiences as well as the ultimate maintenance of the artwork.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Machine Learning–Based Framework for Artwork

Placement and Site Suitability Analysis in Public Art Management

The different reinforcement learning methods can also be used to make simulations of the placement, where the results are repeatedly optimized according to the specified goals, i.e., maximizing the engagement with the population and minimizing the risks of the maintenance. Figure 3 depicts machine learning architecture which studies placement and site suitability of artwork. Such models make recommendations in a scenario form instead of determining the decisions, and human curators are not deprived of creative control. Notably, transparent and trustful stakeholders require explainable machine learning methods in this case. AI-based allocation aids responsible government and culture-conscious planning through exposing the significance of features and making choices. Machine learning can, therefore, add value to evidence-based public art strategies and does not substitute curatorial knowledge and artistic imagination.

4.2. Computer Vision for Condition Monitoring and Damage Detection

Computer vision procedures allow the automatic continuous observation of the works of public art, which overcomes centuries-old conservation and maintenance problems. Exposure of public works to the environment, pollution, weather changes, and human activities subject them to stress, pollution, weather changes, and the costly and unequal controlled inspection of the property. Computer vision systems use data in the form of images and videos taken by cameras, drones, or mobile devices to evaluate the state of the artwork on a large-scale and time-oriented basis. Convolutional neural networks and vision transformers are capable of identifying cracks, discoloration, corrosion, graffiti and structural deformations on the surface with great precision. Comparing sequential images of time allows change detecting algorithms to realize the early signs of material degradation and predictive maintenance instead of reactive restoration. This will help save money on conservation and limit irreparable damage. Object localization and segmentation models also assist in the identification of areas of attack and may be used to guide their specific intervention and effective use of resources. Computer vision systems can be used to match the damage patterns with other external environmental conditions, including humidity, access to sunlight, and air pollution, when coupled with environmental data. Management wise, automated condition check improves accountability and documentation whereby digital records of conservation are generated which are useful in policy compliance and long-term planning.

4.3. Natural Language Processing for Public Feedback and Sentiment Analysis

Natural language processing (NLP) allows systematic processing of the feedback provided by the public to turn various textual inputs into practical insights to include the entire population in the management of art. The social media posts, online reviews, surveys, community forums, participatory platforms express the opinion of different people about artworks, creating bulk mass texts that lack structure. NLP systems like sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and semantic clustering can assist cultural authorities to comprehend the perceptions of the audience, their emotions, and the emerging issues large-scale. Sentiment analysis models separate feedback into a positive, negative, and neutral category, giving quantitative data on how the population received it since the time of processing. Topic modeling can be used to find common themes in the sense of cultural identity, accessibility, symbolism, or controversy and show how the various communities perceive social art. Deeper language models are also able to pick up on more subtle attitudes, sarcasm or context-specific meanings that traditional surveys fail to identify. Multilingual NLP also promotes non-discriminatory interaction in multi-ethnic cities through the analysis of the feedback in other languages and dialects. NLP has been used to enhance participatory governance beyond evaluation in that the community voices are given more prominence during decision making processes. The information gained through the discourse of the people can be used in future commissioning, interpretation methodology, and conflict reduction.

5. Augmented Reality Applications in Public Art Ecosystems

5.1. AR-based preview and simulation of artworks in urban spaces

The preview and simulation visualization AR tools fundamentally change the planning and commissioning processes of public art by allowing stakeholders to project future art pieces into the real environment of the urban environment, allowing them to be seen in reality. Through mobile machines or AR glasses, the planners, artists, and local representatives can have an estimated view of digital copies of works of art at their real size, orientation, and viewpoint in particular locations. This enables one to make an informed assessment of visual harmony, spatial balance, sightlines and interactivity with the surrounding architecture, landscape and pedestrian flow. AR simulations are dynamic responses to lighting conditions, weather, and movement of a viewer unlike the static rendering or physical models, which provide a realistic evaluation of the way art will be perceived in the future. Through management, simulation using AR encourages open decision-making and involvement in consultation. Community individuals are able to interact with proposed installations in planning phases, which offers feedback which is based on lived spatial experience as opposed to abstract representations. This will minimize the chances of controversial situations after the installations and increase popular acceptance. Also, various design options can be tried effectively, and thus, an assessment of artistic, environmental, and accessibility can be made comparative. AR simulations also promote sustainability by reducing the high expenses involved in revisions and wastage of materials in the case of incorrect installations.

5.2. Interactive Storytelling and Contextual Interpretation for Audiences

The manner in which audiences interact with public art is redefined by interactive storytelling via AR because it turns the linear experience of passive audience engagement into an interactive cultural experience. AR allows using physical works of art as a starting point by superimposing digital narratives on the original piece to communicate a layered interpretation that is experienced through action, interaction, and decision-making. These descriptions can contain artist remarks, art history, symbolic commentary, and socio-political commentary that is connected to the site of art. The AR content evolves based on the user orientation when they are going through the space, which provides a custom and interactive interpretative experience. Theoretical approaches to AR storytelling have their basis in the experiential learning and embodied cognition, in which meaning is created by interacting with sensory input and space. AR promotes non-linear narrative, which enables the audience to approach several perspectives and cultural allusions instead of one official and authoritative meaning. The strategy honors plurality of cultures and promotes critical thinking. Participatory prompts, audio and animation are also interactive features that increase emotional connection and memory retention. Accessibility is also enhanced by contextual interpretation through providing a multilingual support, audio description and adaptive interface to the various users such as children and the person with disability.

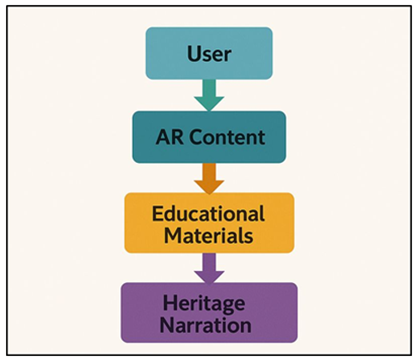

5.3. Educational Overlays and Heritage Narration

An important use of AR in enhancing the educational and cultural benefit of public art is educational overlays and heritage narration. AR can be used to adopt educational content on the street by making use of location-aware digital content; this allows artworks to operate in the street as open air classrooms. Interactive overlays enable users to get explanations of creative methods, materials, historical and cultural symbolism which reinforce formal and informal learning experiences. The advantages of heritage narration by means of AR are especially high in the cities with stratified history and multi-national traditions. AR has potential to recreate lost or modified heritage spaces and place the current public artworks in wider contexts of the different histories. In one example, an overlay can show the development of a site over time or make a linkage of an artwork to indigenous cultures, social movements or local folklore. This strategy ensures continuity of the culture and the passing of knowledge across generations and preservation of physical integrity of heritage sites. In the context of educational theory, AR-based learning can be associated with constructivist models with the focus on self-directed exploration. Figure 4 depicts AR workflow with support of educational overlay and heritage commentary. Learners participate in learning and develop curiosity and a better knowledge.

Figure 4

Figure 4 AR-Enabled Flowchart for Educational Overlays and

Heritage Narration in Public Art

Educational overlays may also be designed to suit the various age groups and educational goals and serve school programs, guided tours, and life long learning programs. Combining art, education, and heritage with immersive technology, AR enhances the purpose of the consideration of the public art as the initiator to cultural literacy, historical consciousness, and sense of community in modern city ecosystems.

6. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

6.1. Data privacy, surveillance, and consent in public spaces

The introduction of AR and AI into the management of art in the public brings up serious issues of data privacy, surveillance, and informed consent in the public. AR applications, as well as AI analytics, are based on the data obtained via sensors, cameras, mobile devices, and interactions with users and can incidentally include personal data or sensitive information. People might not be entirely conscious in the social context that their movements, actions or online interactions are being captured hence, creating ethical conflict between innovation and individual rights. In contrast to the controlled environment, the area of public space makes the process of consent more difficult, since the choice not to take action can be unrealistic or ambiguous. Governance-wise, over-data gathering poses a risk of transforming the cultural spaces into the zones of surveillance, which will destroy the public trust and civic freedom. Strict practices of data minimization, anonymization and purpose limitation are therefore necessary to prevent unethical public art management. Accountability should be based on transparency in policies of data use as well as effective communication with the help of signage or computer displays of such data. Also, the design of the implemented systems should be directed by regulatory frameworks like data protection laws, especially in the situations involving the incorporation of facial recognition or behavioral tracking technologies. To strike a balance between the advantages of the insights backed by data and the consideration of privacy, the need to design human-centered and involve the participation requires human supervision. Ethical benefits can be incorporated into AR-AI systems to ensure that the cultural authorities avoid abuse, maintain the openness, and inclusivity of public art. An ethically sound data custodianship therefore becomes the key to sustainability of legitimate and general trust in culturally enhanced technology enhanced ecosystems.

6.2. Algorithmic Bias and Cultural Representation Risks

The issue of algorithmic bias is a serious ethical challenge to using AI in the decision-making and interpretation of art in the future. The models of machine learning are developed based on past and recent data, which might be characterized by the current social inequalities, prevalent cultural discourse, or biases of the institutions. By introducing these types of biases into the algorithms, they are prone to perpetuate marginalization, minority voices, and give some types of artistic content or cultural expression privileges over others. This may cause inequitable site choices, biased assessment of popular moods or cultural sameness in the background of public art. Cultural representation is complex and situation-specific, and it can hardly be encoded to computational models without making it simple. In AI, it can be called a misperception of symbolic meaning, irony or a reference that is culturally specific as well, especially in multilingual multicultural cities. The excessive dependence on the results of the algorithms can consequently eradicate curatorial diversity and art experimentation. In order to address these risks, there is a need to implement bias-conscious model design, various training data, and ongoing auditing. Human control is still a must in understanding the AI recommendations and making them compatible with the cultural values and principles of social justice. Representational harm can also be minimized by partaking governance approaches in which artists, communities, and cultural experts are incorporated into the system design and assessment.

6.3. Technological Sustainability and Long-Term Maintenance

The practical and ethical difficulties to the application of AR and AI systems to the public art ecosystem are technological sustainability and long-term maintenance. In contrast to the real-life artworks, the digital infrastructures need constant updates, the compatibility of hardware, the administration of cybersecurity, and technical skills. The high rate of technological obsolescence means that in several years, AR applications may become unusable, which will reduce the possibility of access to interpretive information and reduce its value to the population. Sustainability problems are further aggravated by budget constraints and lopsy-lopsy technical capacity in different municipalities. Regarding a lifecycle, environmental effects of digital technologies also are to be taken into account. The use of energy, electronic waste, and cloud infrastructure dependency provokes the concern of support to the goals of sustainable urban development. To approach art management professionally in an ethical manner, the question that needs to be addressed is whether technological interventions will add value to the cultures in the same proportion as their ecological and financial impact. Long-term flexibility requirements can be accommodated by vendor lock-in reduction through modular system design, open standards and interoperability. It is also crucial to have institutional preparedness since the operation of AR–AI systems requires skilled individuals, training, and well-defined governance frameworks.

7. Conclusion

This paper has discussed how Augmented Reality (AR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) can transform the way art is managed by the publics in modern cities. With the increased complexity and ethnic diversity of cities, conventional methods of planning, preserving, and interpreting community art are frequently inadequate to handle issues connected to the spatial appropriateness, viewer involvement, viability and clear-cut management. Through an all-inclusive approach of combining AR and AI in a combined system, managing the art of the people can transform into a non-stagnant cultural system, founded on data, and with active engagement. AR increases the physical and communicative quality of public art by providing an immersive visualization experience, interactive narration, and educational superimposition that builds a more meaningful contact of artworks to their spatial, historical, and social contexts. The AI works in tandem with these functions as it offers analytical intelligence to support decisions, predictive maintenance, and scale massive interpretation of the public responses. Combined, these technologies reinforce the lifecycle-based management approaches that are dynamic to the transformations in urban environments and sensitive to the various community outlooks. Notably, the article highlights that the use of technology innovation should be informed by moral values and the sensitivity of culture. The lack of data privacy, bias in the algorithm, and technological sustainability indicate the necessity of clear governance, human intervention, and non-exclusive policymaking. Ar and AI must not have a substitutionary effect but be the supportive systems which complement curatorial judgment and artistic independence.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al-Kfairy, M., Alomari, A., Al-Bashayreh, M., Alfandi, O., and Tubishat, M. (2024). Unveiling the Metaverse: A Survey of User Perceptions and the Impact of Usability, Social Influence and Interoperability. Heliyon, 10, Article e31413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31413

Alkhwaldi, A. F. (2024). Investigating the Social Sustainability of Immersive Virtual Technologies in Higher Educational Institutions: Students’ Perceptions Toward Metaverse Technology. Sustainability, 16(2), Article 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16020934

Busaada, H., and Elshater, A. (2021). Effect of People on Placemaking and Affective Atmospheres in City Streets. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12(3), 3389–3403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2021.04.019

Cheng, Y., Chen, J., Li, J., Li, L., Hou, G., and Xiao, X. (2023). Research on the Preference of Public Art Design in Urban Landscapes: Evidence from an Event-Related Potential Study. Land, 12(10), Article 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12101883

Gong, Z., Wang, R., and Xia, G. (2022). Augmented Reality (AR) as a Tool for Engaging Museum Experience: A Case Study on CHinese Art Pieces. Digital, 2(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital2010002

Matthews, T., and Gadaloff, S. (2022). Public Art for Placemaking and Urban Renewal: Insights from Three Regional Australian Cities. Cities, 127, Article 103747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103747

Nia, H. A., and Olugbenga, F. (2020). A Quest on the Role of Aesthetics in Enhancing Functionality of Urban Planning. Civil Engineering and Architecture, 8(5), 873–879. https://doi.org/10.13189/cea.2020.080514

Nikoo, M. B., and Sajjadzadeh, H. (2018). The Role of Public Art in Urban Place Making: Case Study of Tehran Urban Parks. Ar-Manshahr: Architecture and Urban Development, 11, 147–158.

Salar, R., Arici, F., Caliklar, S., and Yilmaz, R. M. (2020). A Model for Augmented Reality Immersion Experiences of University Students Studying in Science Education. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 29(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-019-09810-x

Sovhyra, T. (2022). AR-Sculptures: Issues of Technological Creation, their Artistic Significance and Uniqueness. Journal of Urban Culture Research, 25, 40–50.

Sylaiou, S., Dafiotis, P., Fidas, C., Vlachou, E., and Nomikou, V. (2024). Evaluating the Impact of XR on user Experience in the Tomato Industrial Museum “D. Nomikos”. Heritage, 7(3), 1754–1768. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7030082

Uriarte-Portillo, A., Ibáñez, M.-B., Zataraín-Cabada, R., and Barrón-Estrada, M.-L. (2022). Higher Immersive Profiles Improve Learning Outcomes in Augmented Reality Learning Environments. Information, 13(5), Article 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13050218

Wang, Y. (2022). The Interaction Between Public Environmental Art Sculpture and Environment based on the Analysis of Spatial Environment Characteristics. Scientific Programming, 2022, Article 5168975. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5168975

Wang, Y., and Lin, Y.-S. (2023). Public Participation in Urban Design with Augmented Reality Technology based on Indicator Evaluation. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 4, Article 1071355. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2023.1071355

Young, T., and Marshall, M. T. (2023). An Investigation of the Use of Augmented Reality in Public Art. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7(9), Article 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7090089

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.