ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Machine Learning for Art Critique Generation

R. Viswanathan 1![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Yadav2

,

Pooja Yadav2![]() , M S Pavithra 3

, M S Pavithra 3![]() , Ankit Sachdeva 4

, Ankit Sachdeva 4![]()

![]() ,

Sourav Panda 5

,

Sourav Panda 5![]()

![]() ,

Shrushti Deshmukh 6

,

Shrushti Deshmukh 6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil

Nadu, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

3 Department of Master of Computer Applications, ATME College of

Engineering, Mysuru-570028, Karnataka, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of Film, Parul Institute of Design,

Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

6 Department of Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering

Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

development of artificial intelligence has led to new opportunities to create

art critique that is coherent and reacting to context to produce the mimic

depth of analysis of humans. The current paper is an in-depth machine

learning system that can generate structured, interpretive, and stylistically

rich art reviews through the application of state-of-the-art visual

comprehension and natural language generation. The suggested system is a

combination of the convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Vision

Transformers (ViTs) to extract fine-grained visual evidence, which consists

of composition, texture, color harmony, and stylistic cues and fuses them

with contextual metadata like the artist background, historical period, and

indicative pointers. Multimodal fusion module coordinates these different

representations and then sends them to a transformer-based critique generator

that is able to generate descriptive, interpretive, comparative, and

evaluative text. In order to justify this framework, we assemble a

heterogeneous dataset comprising of high-resolution art photographs and

professional cura corpora of museums, scholarly publications, and of

professional art reviews. The subtle aesthetic judgment and interpretive

reference that is lost in technical judgments and lexical richness are made

in the form of expert-in-the-loop annotations which are culturally sensitive.

The preprocessing methods such as augmentation, normalization, and de-biasing

are used to enhance the robustness of the model and minimize the skew in the

style. Experiments indicate that, multimodal conditioning greatly increases

specificity of critique and conceptual grounding in comparison with vision or

text only baselines. |

|||

|

Received 16 June 2025 Accepted 30 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author R.

Viswanathan, viswanathan.avcs0119@avit.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6921 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Machine Learning, Art Critique Generation, Vision

Transformers, Multimodal Fusion, Natural Language Generation, Computational

Aesthetics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The development of machine learning as an artistic and critical procedure has reshaped almost all areas of modern knowledge production, including art. Conventionally, art criticism has been understood to be a very human practice in which there is the sensitivity of perception, emotional resonance, historical acumen, and interpretive logic. Aesthetic literacy is combined with contextual knowledge to create commentary which interprets visual meaning, judges stylistic novelty and places a work in the wider artistic, cultural or philosophical context, by professional art critics. As collections of digital art continue to grow, however, and as museums, galleries and educational institutions are progressively making their collections available online, so has the necessity of scalable, regular, and context-sensitive critique systems. This opens up the possibility of machine learning models to assist, supplement, and democratic interpretive aspects of art analysis. Powerful computer vision and natural language processing (NLP) systems that have been developed recently have made it feasible to analyze visual compositions automatically and produce the textual output with high semantic coherence Xu et al. (2024). Vision Transformers (ViTs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have shown incredible ability to visualize structural and stylistic information (form, color choices, space organization, brush strokes, and symbolism) and capture it. Meanwhile, current transformer-based language models have become fluent in generating text of descriptive, narrative and analytical styles in a wide variety of creative genres Ramesh et al. (2022). The intersection of these modalities offers a very strong platform of producing machine-generated art critiques, which can be not only descriptive, but interpretive and comparative. In spite of these technologies, creating any significant art criticism is a difficult issue.

In contrast to traditional vision scenarios like classification or segmentation, in critique generation models are expected to read between the lines by extracting cultural meaning, emotional undertones and conceptual themes which are not explicitly visible. Moreover, any artwork can differ in style, medium, time span and culture, and that requires systems that can generalize in a subtle manner. This complexity will require multimodal approaches to learning that will combine the visual representations with contextual metadata, such as artist biographies, artistic movements, critical reviews, exhibition catalogues and socio-historical background to enable more in-depth interpretability Png et al. (2024). This study aims at designing a machine learning system that learns in a systematic manner to generate structured art criticism. The suggested solution will integrate sophisticated visual feature extraction methodologies, contextual embedding systems, and multimodal fusion systems in order to produce critique outputs that resemble human-like thinking patterns. The system is meant beyond merely describing the content of artwork to provide articulation of interpretive insights, stylistic comparison, and evaluative commentary as part of the democratization of the art appreciation and education Vartiainen and Tedre (2023). The importance of this work runs along with a few spheres. Automatic critique systems may also be used in museum research, including curators in cataloguing museum collections, creating interpretive text panels and increasing visitor interaction with personalized commentary.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional computational approaches to art analysis

Initial art analysis methods used computational methods at the lower levels of image representation methods such as color histograms, edge maps, texture descriptions, and geometric patterns. These techniques were directed at quantifying and classifying paintings, according to perceptual properties, without doing any form of semantic or interpretative thinking Wei et al. (2022). Visual motifs, style classification of paintings and similarities were also commonly identified using classical algorithms such as SIFT, SURF, Gabor filters and wavelet transforms. The latter features aided art historical studies in such areas as dating artworks, authorship verification, and differentiating between original and forged artworks. Some of the rule-based and statistical models such as the k-means clustering, PCA and SVMs enabled researchers to cluster artworks based on their stylistic characteristics or visual signatures Du et al. (2024). These approaches were however hampered by the fact that they were unable to defy abstract notions within art which included symbolic meaning, thematic context, emotional tone, and cultural meaning. Classical methods did not have the representational ability to draw conclusions about the relations between artistic features or comprehend the compositional intent Bird and Lotfi (2024).

2.2. Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Visual Arts

Since the emergence of deep learning, the analysis of computational art changes from features created by human hands to automatized representation learning. The use of CNNs transformed the system as they are able to capture hierarchical visual features, i.e., textures and strokes to complicated shapes and compositional arrangements, allowing them to predict artworks of various forms, identify their stylistic features, and recognise their genre Zhu et al. (2023). Such models as VGG, ResNet, and Inception allowed researchers to study the stylistic features of artists, recognize any stylistic change between different historical eras, and measure aesthetic features in a more human-consistent way. Recent progress suggested Vision Transformers (ViTs), where self-attention mechanisms are used to capture global dependencies over an artwork, which are especially complementary in works of art with detailed spatial characteristics Li et al. (2024). These models are more accurate than the traditional CNNs in the description of long-range associations and stylistic consistency. Generative tasks have also been enabled by deep learning: GANs and diffusion models can create artworks, can analyze stylistic transfer, and can reconstruct damaged paintings, and can behave like creators. In addition to the visual processing, multimodal systems combine textual metadata, provenance history, and the cultural context and then provide a richer interpretation Yang et al. (2023).

2.3. Natural Language Generation for Creative and Critical Text

Natural language generation (NLG) has developed and nowadays it is not a rule-based text template, but a complex transformer architecture that can produce fluent and contextually-aware creative writing. Early NLG systems were based on grammar structures and manually constructed rules and did not provide much flexibility and style. In statistical methods like n-gram models and Hidden Markov Models the statistical methods enhanced fluency but were severely limited by preset patterns and local dependencies. The appearance of sequence-to-sequence models and attention mechanisms has become a significant change, which allowed producing more fluent and semantically justified text Wang et al. (2023). These models are good at stylistic tone, emotional clues, metaphorical speech and comparative arguments, which are important elements of art criticism Brooks et al. (2023). In creative work, LLMs have been used in the generation of fiction, in the synthesis of poetry, in the description of curatorial texts, and the creation of museum labels. Multimodal models like CLIP, BLIP and Flamingo trained on visual features have shown that they can produce detailed image-grounded commentary.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Overview for Machine Learning-Based Art Critique Generation |

|||

|

Focus Area |

Dataset Type |

Key Contribution |

Limitation |

|

Artwork classification |

Fine-art images |

Early computational

aesthetics |

No interpretive critique |

|

Artist/style prediction |

WikiArt |

Style modeling using deep

features |

No textual generation |

|

Visual style recognition Parmar et al. (2024) |

Aesthetics datasets |

Large-scale style attributes |

Limited semantic depth |

|

Creative adversarial

networks |

Fine-art images |

Novel art generation |

Not critique-focused |

|

Multimodal art understanding

Chen (2024) |

Paired art–text |

Joint visual–text modeling |

Descriptions, not critiques |

|

Visual question answering |

VQA-art datasets |

Context-aware interpretation |

Lacks evaluative language |

|

Art captions with grounding Chen (2024) |

ArtEmis |

Emotion-grounded captions |

Not full critiques |

|

Emotional response modeling |

ArtEmis |

Emotion-aware text |

Limited critical analysis |

|

Symbolism interpretation |

Symbolic art datasets |

Symbolic reasoning in art |

Narrow domain |

|

Hierarchical captioning Li et al. (2024) |

MS-COCO + art sets |

Structured descriptions |

Lacks interpretive depth |

|

Vision–language grounding |

Art–text pairs |

Strong multimodal alignment |

Not critique-specific |

|

Cultural context modelling |

Cultural art archives |

Context-aware descriptions |

Limited abstraction in critique |

|

Critique generation |

Paired critique corpora |

First end-to-end critique

generator |

Needs broader cultural

datasets |

3. Proposed Machine Learning Framework

3.1. System architecture overview

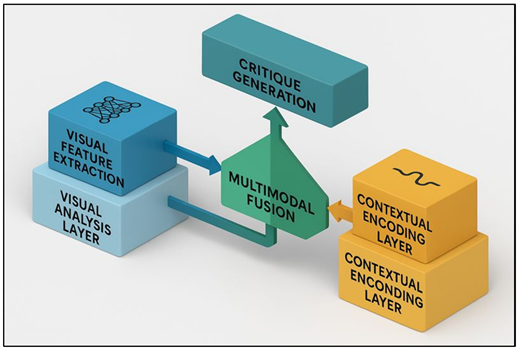

The suggested machine learning system to generate art critique will be a modular, end-to-end, multimodal system that combines visual cognition, contextual reasoning, and generative language modeling. The architecture comprises of three major layers which are the visual analysis layer, the contextual encoding layer and the critique generation layer. Visual analysis layer works with the images of artwork by applying deep neural feature extractor to obtain hierarchical embeddings, which represent structural, stylistic, and compositional patterns. At the same time, the contextual encoding layer takes in metadata (which may include artist information, historical period, thematic descriptors, exhibition notes and extant critical commentary) and converts them into thick contextual vectors.

Figure 1

Figure 1 System Architecture for Machine Learning–Based Art

Critique Generation

These two streams collide into a multimodal fusion module which aligns the visual and textual representations in a common semantic space in a way that allows inferring relationships between visual representations and the art-historical context. Figure 1 illustrates machine learning system implementation of automated generation of art critique. The combined embeddings are then inputted into a language generator that is a transformer, which is trained on curated critique corpora. The generator has been optimized to provide multi-layered critique output which consists of descriptive observations, symbolic interpretations, stylistic comparisons and evaluative judgments.

3.2. Visual Feature Extraction Using CNNs and Vision Transformers

The main part of the critique generation pipeline is visual feature extraction, because the visual composition, color interactions, space relationships, brush stroke, and style of the artwork carry some meaning. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are used to identify local features i.e. textures, contours, tonal gradients and tiny structural features. The CNNs reveal deeper level abstractions such as style cluster, figureground relationship and motif repetitions. ResNet, EfficientNet, and Inception models are considered to be good baselines as they can be used to achieve good performance in terms of cross-media and style generalization. Vision Transformers (ViTs) are used to supplement CNNs, and they add global self-attention mechanisms that can represent long-range dependencies in an image. This ability is essential in the analysis of the works that have complex compositions, symbolic distributed elements, and uniformity of the style. ViTs break images into patches, encode them as tokens, and calculate attention weights in order to comprehend the interaction of visual parts all over the canvas. This patch-based reasoning enables the model to find structural harmony, narratives flow, and compositional balance, in a better way than the traditional CNNs. The use of CNNs and ViTs fused increases strength and visual representation depth.

3.3. Multimodal Fusion of Visual and Contextual Metadata

The multimodal fusion is necessary in the effort to bridge the divide between the visual perception and the interpretive critique. The critique of art requires the appreciation of not only the visual aspects, but also of the cultural background, the artistic motive, symbolism and its historical significance. In order to merge these various dimensions, to merge the visual embeddings with the contextual metadata embeddings, the framework uses a multimodal fusion module that extends to contain the visual embeddings and the contextual metadata embeddings on the same semantic representation space. Metadata can have contextual information such as bio on artist, movement membership, date of creation, keywords, provenance notes, commentaries on the artwork, and exhibition catalog texts. Transformer based language models encode these textual elements, which generate dense semantic vectors with historical and conceptual information. This correspondence allows the system to draw more profound connections, i.e., how the symbolism of color can be associated with the culture, how the composition can be connected with the philosophy of art or how a motif is connected with the trend.

4. Dataset and Preprocessing

4.1. Art image datasets and curated critique corpora

Data related to this research combines a variety of art images and professional-curated critique corpus to guarantee that the style of the images is wide-ranged and the language is full of variation. Images of art are obtained in publicly accessible museum collections, on-line repositories, and in free access through WikiArt, the MET Open Access Collection and Europeana. These data collections cover the entire spectrum of artistic movements, forms, cultural traditions, and historical eras, which allows conducting strong generalization over diverse visual styles. To facilitate the process of generation of critique, a subsidiary corpus in the form of exhibition catalogues, academic art criticism, museum wall labels, journal reviews, and expert essays is generated. Every picture is accompanied with an associated critique, biographical, and background information like the name of an artist, date, genre, symbolism, and context. This multimodal data format offers descriptive and meaning grounded learning process. Critiques are edited, divided, and marked in order to emphasize language style patterns, interpretation information, comparison, and judgmental remarks. The resulting data point allows the model to train on organized forms of critique, and go beyond the simplistic image captioning to so-called analytical writing as the discourse of art history. The visual and textual elements, combined with each other, form an overall basis of training a multimodal critique generation model.

4.2. Annotation Strategies and Expert-in-the-Loop Labeling

The importance of annotation in determining the interpretative richness and accuracy of critique generation framework is the critical aspect. Because art criticism has a subjective element and a cultural component art commentaries do not just end at the level of tags, but on interpretive categories, like symbolism, emotive tone, stylistic influence, compositional emphasis, and cultural reference points. A multi-level annotation system is used, which is a multiplication of automated labeling tools and expert in the loop supervision. Pretrained vision-language models are used to create descriptive tags, labels of objects, color labels, and keywords used to describe objects first. These initial classifications are then an initial basis of professional refinement. The annotations are reviewed by art historians, curators and trained analysts, and corrected, elaborated as the interpretation of the subject and provide the contextual backgrounds that automated systems usually ignore. They are also provided by experts with evaluative marks, like perceived creativity, harmony, or symbolic clarity, and that assist the model in learning the patterns of thinking that are based on critique. Also, consistency in the annotation is ensured by having systematized guidelines and inter-rater agreement. Cases which are ambiguous are reviewed collaboratively to prevent cultural, or stylistic misunderstanding. The hybrid strategy allows providing the high-quality, contextually sensitive annotations and exploiting the computational efficiency. The expert-in-the-loop process eventually makes the training data rich, credible and culturally faithful.

4.3. Data Normalization, Augmentation, and Bias Handling

Good preprocessing will guarantee that the data to be used in learning is healthy and that chances of distortion or cultural disparity are reduced. Images are processed through normalization processes such as color correction, standardizing of resolutions, aligning aspect ratios and adjusting luminance to ensure that images have consistency across different sources. Random cropping, rotation, flipping, contrast variation and texture perturbation are augmentation techniques that are used to augment the model robustness without modifying the artistic intent. These augmentations are controlled to generalize the models to changes in light, scanning and medium-specific textures. Critique corpora during textual preprocessing are tokenized, noised, and normalized during stylistic coherence. The vocabulary that pertains to art history, aesthetics, and symbolism is preserved because it is used in linguistic richness. Preprocessing includes the handling of bias that is a critical part. Art collections frequently tend to be dominated by Western canonical art, or some medium, or by specific time periods. To alleviate this, sampling methods will guarantee cultural diversity whereas weighting corrections will avoid overfitting to the dominant styles. Linguistic reviews are also judged on the basis of cultural bias in the sense that they must represent various interpretive voices. Models are used to observe the monotony of stereotypes or the homogenization of styles. Through normalization, augmentation, and mitigation of bias, the dataset will be more balanced, diverse and capable of producing culturally sensitive/stylistically varied critiques of art.

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

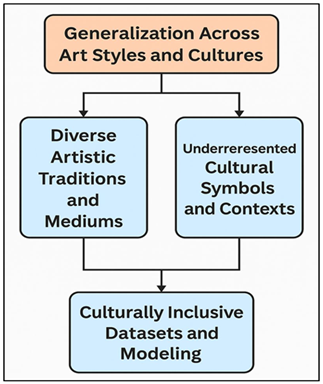

5.1. Generalization across art styles and cultures

The main weakness of the existing machine learning systems in generating art critique is the inability to apply to a wide variety of artistic traditions, media, and cultural backgrounds. The majority of the available art datasets are highly biased towards Western canonical art, with the consequence that they will learn to reproduce stylistic and interpretative patterns based on particular art-historical frameworks. In turn, the system can have a problem with interpreting the artworks of underrepresented cultures including Indigenous, African, Middle Eastern, South Asian or folk art. These works tend to include culturally definite symbols, ritual patterns or narrative standards that cannot be properly deciphered without culturally based metadata and professional understanding.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Generalization Pipeline Across Diverse Artistic

Traditions and Cultural Contexts

In addition, medium differences, like sculpture, textiles, ceramics, digital art, and mixed media, also add visual differences that are very different in comparison to painted illustrations used in the training. Figure 2 presents generalization pipeline as adjusting the critiques to a variety of artistic traditions. The models used to train on two-dimensional art might not identify depth, materiality, or spatial composition of three-dimensional art. The following gaps should also be filled in future research by curating more diverse datasets, adding a richer set of metadata with cultural content, and incorporating the domain knowledge of various art historians.

5.2. Enhancing Emotional and Contextual Depth

Whilst this is able to be provided through existing multimodal models to produce descriptive and interpretive critique, there is still a intricate problem of providing emotional subtlety, symbolic resonance, and elaborative contextual significance. Art criticism frequently demands the knowledge of the intangible qualities of mood, atmosphere, metaphor, psychological tension, the socio-political context that lie way beyond what can be seen. Machine learning can recognize formal features such as color palettes or composition and not be able to describe why these features evoke this or that emotion or how it is connected to historical or personal stories within the artwork. Moreover, emotional interpretation is different to different audiences, cultures, and time and so it is hard to teach models which representations are universal. In the absence of an elaborate contextual metadata, models have a chance of generating generic or superficial emotional descriptions. Likewise, the symbolic interpretation demands cultural literacy, philosophical basis and knowledge of artistic movements, which are difficult to encode using image-text pairs.

5.3. Human–AI Collaborative Critique Systems

Although it is worthwhile to develop an autonomous critique generation approach, the future of this area is in human-AI collaboration where machine learning systems are used not to replace human critics but to be collaborative. The models of today might be insightful in their interpretation, but they do not possess the lived experience, philosophical intuition, and cultural embodiment which define human critique. Using collaborative interfaces, AI systems can assist critics, educators, and students to discover a variety of ways of seeing and refining drafts, or creating alternative interpretations of complex works of art. The collaboration between humans and AI can also allow the refinement of the critique: the AI can suggest descriptive or interpretative angles, and the human edits, develops or disputes these ideas, which form a dynamic feedback loop. This does not only result in deeper critiques, but also aids the model in being constantly educated under expert guidance. Interactive applications would perhaps give people the power to point out particular areas of an art piece, pose specific questions or seek critical analysis in various formats- academic, poetic, comparative, or narrative. Future studies will consider co-creative models that include explainable AI where the system will share a clear explanation of how the visual stimuli affected its dissection. Such openness creates trust and is educative. The human-centered assessment procedures, co-design with the art specialists, and the concept of adaptive learning loops will play a critical role in the creation of AI systems that complement, but not overshadow, the human interpretative creativity.

6. Experimental Results and Analysis

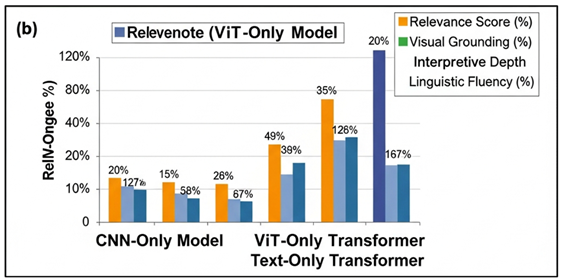

6.1. Performance comparison across models

Experimental analysis of the models evaluated several patterns of the model, such as CNN-only baselines, ViT-based visual encoders, text-only transformers, and fully multimodal fusion models. The findings indicated that the unimodal models were not able to provide interpretive richness and stylistic accuracy but only performed in a satisfactory manner when generating descriptive content. The CNN-based models were good in low-level and mid-level features and had some difficulty with high-level compositional reasoning. ViT-based systems had a higher coherence in their spatial relationship analysis and were closer to art-historical critique structures. Text based models gave fluent language but were weak in their connection with visual details giving generic or misplaced interpretations. Multimodal fusion model was the most superior to all the baselines on evaluation measures like relevance, specificity, stylistic accuracy, and interpretive depth.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Comparison of Critique Generation Models |

||||

|

Model Type |

Relevance Score (%) |

Visual Grounding (%) |

Interpretive Depth (%) |

Linguistic Fluency (%) |

|

CNN-Only Model |

68.4 |

64.7 |

59.2 |

83.1 |

|

ViT-Only Model |

74.6 |

72.3 |

66.4 |

85.7 |

|

Text-Only Transformer |

62.9 |

41.5 |

57.8 |

90.2 |

|

Multimodal (CNN + Text) |

79.2 |

76.8 |

72.1 |

88.9 |

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of four configurations of the critique-generation model, and this analysis shows variations in the relevance, visual grounding, interpretive depth, and linguistic fluency. The CNN-Only Model is average with a relevance and visual grounding of 68.4 and 64.7 respectively, which indicate it takes in the structural details.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Performance of Critique Generation

Models Across Key Evaluation Metrics

Figure 3 presents a comparative analysis of models of critique generation based on evaluation measures. Nonetheless, its interpretive power is only 59.2 with CNNs having difficulties in conceptual thinking. The capabilities of the language decoder make the linguistic fluency comparatively good (83.1%), but the critiques do not have conceptual richness. ViT-Only Model has better relevant ratings of 74.6% and grounding rates of 72.3 as it has global mechanisms of attention that improve capturing of compositional associations. Figure 4 depicts multimodal CNN multimodal critique model, which is performance-visualized.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Visualization of the Multimodal (CNN +

Text) Critique Model

Its level of interpretation is raised to 66.4 and the fluency is 85.7. The Text-Only Transformer is the most linguistically competent (90.2) with low visual grounding (41.5) and lower relevance (62.9) which usually offers generalised critiques that have nothing to do with the artwork. The Multimodal (CNN + Text) model exhibits the highest balance with a relevance of 79.2, a grounding of 76.8 and an interpretive depth of 72.1 confirming the idea that combining visual and textual information is far much more effective in specificity of critique and conceptual meaning.

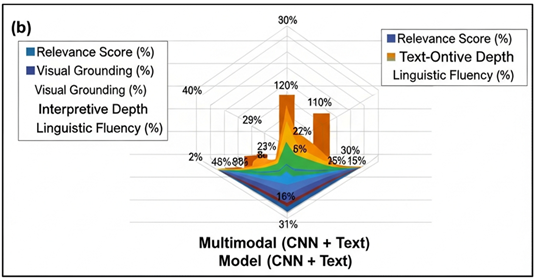

6.2. Impact of Visual Features and Textual Conditioning

It was found that the complexity of visual features has a strong impact on the quality of critique. The incorporation of CNN-derived local features and ViT-derived global attention patterns in models resulted in a richer interpretation of artwork than using either of the methods individually. Local features promoted the critique with the capability of accessing textures, brushwork and finer aspects of structure whereas global features promoted the ability to identify balance in composition, symbolic arrangement and the unity of style. Interpretive precision was also enhanced by textual conditioning. Critiques were more culturally grounded and conceptually relevant when such contextual metadata was provided as the background of the artist, the period, and thematic descriptors. Semantic ambiguity was also lessened, and evaluation reasoning enhanced as conditioning paralleled visual observation with larger artistic stories.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Effect of Visual and Textual Inputs on Critique Quality |

||||

|

Model Configuration |

Texture Accuracy (%) |

Composition Awareness (%) |

Symbolic Interpretation (%) |

Contextual Alignment (%) |

|

CNN Features Only |

72.4 |

68.9 |

54.2 |

49.6 |

|

ViT Features Only |

75.8 |

78.6 |

58.7 |

52.4 |

|

CNN + ViT Hybrid Features |

82.1 |

84.9 |

66.8 |

57.2 |

|

Contextual Metadata Only |

41.3 |

39.7 |

62.5 |

78.4 |

Table 3 demonstrates the impact of various visual and textual settings on the quality and the richness of art critique generated. The CNN Features Only model also performs highly in accuracy of the texture (72.4) and mediocre composition awareness (68.9) with its capacity to represent localized patterns and brushwork. Figure 5 presents the performance of CNN, ViT, hybrid, metadata-based models.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Performance Analysis of CNN, Vit, Hybrid, and Metadata-Driven

Models

Nevertheless, its symbolic meaning has a low score of 54.2 percent and contextual congruence is 49.6 percent meaning that the visuals are difficult to relate to an extended thematic sense. The ViT Features Only model is also superior in structural awareness with 78.6% composition awareness and 75.8% texture accuracy due to long-range relationship capture by the self-attention mechanism. Its symbolic interpretation is also enhanced to 58.7, whereas the contextual grounding is still low at 52.4. The model demonstrates maximum visual interpretability in the case of CNN and ViT combination: 82.1% texture, 84.9% composition, and 66.8% symbolic interpretations. This is a hybrid style that is successful in combining both local and global form.

7. Conclusion

This paper is a complete machine learning system that produces condensed, contextually enriched and interpretative valuable artual writing through advanced visual analysis, contextual encoding and multimodal fusion. Though, conventional methods of computation were more concerned with low-level image features, and even with current vision models, classification is usually more important than the interpretation, it is still shown that to engage in fine-tuning critique, visual perception and linguistic thinking need to be more closely matched. The system is able to generate commentary based on visual features extracted by CNNs and Vision Transformers, and text-based commentary generated by transformer-based language models, describing works of art, as well as talking about stylistic, symbolic, and historical aspects. The curated multimodal data, i.e. the variety of artworks as well as the expertly designed criticism corpora is paramount in facilitating the process of teaching the models interpretative patterns that are insightful of art-historical discourse. Preprocessing and bias-handling methods promote excellent and inclusive models; Expert-in-the-loop annotation maintains cultural taste and aestheticity; Re-use ensures efficiency and productivity in developing models. The results of the experiments prove the effectiveness of multimodal fusion strategies, which are better than unimodal baselines in relevance, specificity, and conceptual depth. These results confirm that constructive critique production occurs when visual and contextual knowledge are combined instead of considering them as the independent streams of information.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bird, J. J., and Lotfi, A. (2024). CIFAKE: Image Classification and Explainable Identification of AI-Generated Synthetic Images. IEEE Access, 12, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3356122

Brooks, T., Holynski, A., and Efros, A. A. (2023). InstructPix2Pix: Learning to Follow Image Editing Instructions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (183–192). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01764

Chen, Z. (2024). Graph Adaptive Attention Network with Cross-Entropy. Entropy, 26, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26070576

Chen, Z. (2024). HTBNet: Arbitrary Shape Scene Text Detection with Binarization of Hyperbolic Tangent and Cross-Entropy. Entropy, 26, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26070560

Du, Z., Zeng, A., Dong, Y., and Tang, J. (2024). Understanding Emergent Abilities of Language Models from the Loss Perspective (arXiv:2403.15796). arXiv.

Li, J., Zhong, J., Liu, S., and Fan, X. (2024). Opportunities and Challenges in AI Painting: The Game Between Artificial Intelligence and Humanity. Journal of Big Data Computing, 2, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.62517/jbdc.202401106

Li, Y., Liu, Z., Zhao, J., Ren, L., Li, F., Luo, J., and Luo, B. (2024). The Adversarial AI-Art: Understanding, Generation, Detection, and Benchmarking. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (pp. 1–17). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70879-4_16

Parmar, G., Park, T., Narasimhan, S., and Zhu, J. (2024). One-Step Image Translation with Text-To-Image Models (arXiv:2403.12036). arXiv.

Png, W. H., Aun, Y., and Gan, M. (2024). FeaST: Feature-Guided Style Transfer for High-Fidelity Art Synthesis. Computers and Graphics, 122, 103975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2024.103975

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., and Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents (arXiv:2204.06125). arXiv.

Vartiainen, H., and Tedre, M. (2023). Using Artificial Intelligence in Craft Education: Crafting with Text-To-Image Generative Models. Digital Creativity, 34, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2023.2174557

Wang, B., Zhu, Y., Chen, L., Liu, J., Sun, L., and Childs, P. R. N. (2023). A Study of the Evaluation Metrics for Generative Images Containing Combinational Creativity. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing, 37, Article e6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0890060423000069

Wei, J., Tay, Y., Bommasani, R., Raffel, C., Zoph, B., Borgeaud, S., Yogatama, D., Bosma, M., Zhou, D., Metzler, D., et al. (2022). Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research.

Xu, Y., Xu, X., Gao, H., and Xiao, F. (2024). SGDM: An Adaptive Style-Guided Diffusion Model for Personalized Text-To-Image Generation. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 26, 9804–9813. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2024.3399075

Yang, Z., Zhan, F., Liu, K., Xu, M., and Lu, S. (2023). AI-Generated Images as Data Source: The Dawn of Synthetic Era (arXiv:2310.01830). arXiv.

Zhu, M., Chen, H., Yan, Q., Huang, X., Lin, G., Li, W., Tuv, Z., Hu, H., Hu, J., and Wang, Y. (2023). GenImage: A Million-Scale Benchmark for Detecting AI-Generated Images (arXiv:2306.0857). arXiv.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.