ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dance Pose Optimization

P. Thilagavathi

1![]()

![]() ,

Digvijay Pandya 2

,

Digvijay Pandya 2![]()

![]() ,

Asha P. 3

,

Asha P. 3![]()

![]() ,

Prince Kumar 4

,

Prince Kumar 4![]() , Leena Deshpande 5

, Leena Deshpande 5![]() , Jaspreet Sidhu 6

, Jaspreet Sidhu 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies, Jain (Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

3 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

4 Associate Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, Uttar Pradesh, India

5 Department of Computer Engineering (Software Engineering), Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune 411037, Maharashtra, India

6 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura

140417, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Deep

Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has become an effective framework of sequential

decision-making in high-dimensional and complex control problems, but little

has been done to apply it to expressive human movement. This work is a

unified DRA algorithm to optimize a dance pose, which an intelligent agent is

trained to produce the smooth and stable dance pose

and aesthetically compose a pose in a simulated kinematic environment.

Generation of dance poses is modeled formally as a Markov Decision Process

with incorporation of joint level kinematics, time related dependencies and

balance constraints in the state space and pose corrections expressed as a

continuous control action. The given framework incorporates pose estimation

results and biomechanical constraints to guarantee physical feasibility and

motion synthesis that is safe of injuries. Several types of DNR algorithms

are tested such as Deep Q-Networks, Proximal Policy Optimization, and

Actor-Critic variants to determine their appropriateness to fine-grained pose

refinement. The pose accuracy, motion smoothness, energy efficiency and

balance stability are well coordinated in a reward function that allows a

multi-objective optimization that is in line with technical correctness and

artistic quality. Curriculum learning is used to bring a gradual complexity

to the poses so that the agent is able to move on to

dynamic dance patterns. Substantial experimental investigation shows that

policy-gradient-related techniques are more convergent stable and realistic

than value-based baselines. |

|||

|

Received 20 June 2025 Accepted 04 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author P. Thilagavathi, thilagavathi.avcs093@avit.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6909 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Deep

Reinforcement Learning, Dance Pose Optimization, Human Motion Modelling,

Markov Decision Process, Kinematic Constraints |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

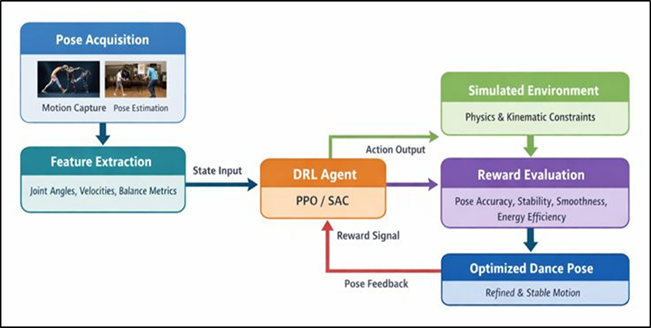

Dance is a very organized at the same time expressive type of movement of a man that combines biomechanics, rhythm, emotion and artistic intention. Optimization of dances poses and transitions has been core to the use of expert choreographers, instructors and repetitions, which makes the process time consuming and subjective. Due to the fast development of artificial intelligence, especially machine learning and computer vision, computational methodology is becoming a growing research area to model, analyze, and improve human motion. One of them, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), provides an interesting paradigm of learning the optimal strategies of movements based on interaction, feedback, and optimization of long-term rewards. Optimization of the dance pose through DRA gives rise to new possibilities of the intelligent trainers, automated support of the choreography and analysis of the performance. Dance pose optimization is the production or optimization of forms of the body that fulfill a variety of, usually competing, goals. These are kinematic feasibility, balance stability, temporal smoothness, energy efficiency and aesthetic coherence. The problem with classical optimization and rule-based motion synthesis algorithms is that it is difficult to scale to high-dimensional and continuous as well as temporally dependent human dance motions Lei et al. (2022). Though well-suited to pose estimation and motion prediction problems, supervised learning methods are constrained by the existence of labeled data, and have no explicit optimism of long-horizon performance objectives. Compared to it, DRL models sequential decision-making problems naturally and allows agents to optimize control policies that maximize cumulative rewards, and thus is well applied to complex motion optimization problems. DAO Dance pose optimization A control problem can be defined in a DRA environment in which an agent optimizes the joint configurations to attain desirable poses and transitions. Figure 1 demonstrates that it is possible to integrate states, rewards and policies to maximize dance poses. The agent monitors the present position of the dancer such as the angles of the joints, velocities, balance cues and time and decides what to do to alter the pose as time progresses. The agent discovers strategies through trial and error that do not only reproduce target poses, but also preserve physical plausibility as well as expressive continuity Zhai (2021).

Figure 1

Figure 1 Deep Reinforcement Learning–Based Framework for Dance Pose Optimization

The given learning paradigm is quite similar to the way human dancers learn and become better at it due to the feedback, practice, and possible refinement, which is another reason to consider the reinforcement learning implementation in the specified area. The recent progress in pose estimation, physics-based simulation, and differentiable kinematic modelling have greatly reduced the difficulty of applying DRL to human movement Jin et al. (2022). Skeletal tracking can be done with accuracy to track states in detail, and physics-aware environments can impose biomechanical constraints, and exclude unrealistic motion artifacts.

2. Related Work

The research of optimization of dance poses falls at the cross-section of human motion analysis, pose estimation, motion synthesis, and reinforcement learning. Early computational methods of simulating dance and human motion were based mainly on kinematic laws and physics-based methods of animation. These were based on the inverse kinematic, motion capture retargeting, and constraint optimization to guarantee joint limit consideration and balance stability Dias Pereira Dos Santos et al. (2022). Proven to be useful at creating physically plausible poses, those techniques were not adaptive and could not learn variability in the style or maximize the quality of motion over the long term across sequences. Supervised models have taken over in the field of human pose estimation and motion prediction with the development of deep learning. Convolutional neural networks and graph-based models have been prevalently employed to predict 2D as well as 3D skeletal poses using video inputs as their base layer, upon which tasks of downstream motion analysis are based Davis et al. (2023). Temporal convolutional and recurrent neural networks also allowed short-term predictions of motion and pose sequence smoothing. Nevertheless, these are guided methods whose ability to support global goals, like balance, energy-efficiency or aesthetic continuity of dance motions, is restricted by labelled data and usually optimizes frame-wise reconstruction loss. It has also been found that reinforcement learning is actively studied in human motion control, especially in robotics and in character animation Choi et al. (2021).

DRA Physics-based DRA systems have shown to be able to learn locomotion, balance, and complicated motor skills like walking, running, and acrobats. It has been demonstrated that policy gradient and actor actorcritic methods are more successful than value-based methods in continuous control tasks with high action space dimensions. Through these studies, reinforcement learning has the potential to learn the long-horizon dependencies and optimize the quality of movement with a well-constructed reward function Guo et al. (2022). Also more modern efforts have started to use DRL to generate expressive motions and tasks aimed at performance, such as gesture generation, music-driven movement generation and dance choreography generation support. Others use motion capture information as reference trajectories, and the imitation learning is reinforced to speed up convergence, and the stylistic characteristics are maintained. Others concentrate on reward shaping methods which entail the rhythm consistency, fluent motion and symmetry to promote aesthetically fulfilling movements Esaki and Nagao (2023). Table 1 provides an overview of previous literature that combines human motion, dance modelling and reinforcement learning despite these progressions, the current methodologies generally focus on producing full-body motions and not fine-grained pose optimization nor integrating biomechanical constraints.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work on Human Motion,

Dance Modelling, and Reinforcement Learning |

||||

|

Application

Domain |

Learning

Paradigm |

Motion

Representation |

Key

Optimization Objective |

Limitations |

|

Character

Animation |

DRL

(Actor–Critic) |

Full-body

joints |

Balance

& locomotion |

Limited

expressiveness |

|

Human

Locomotion |

DRL

(PPO) |

MoCap

skeletal data |

Motion

imitation |

Style

rigidity |

|

Dance

Generation Chan et al.

(2011). |

Supervised

DL |

Joint

trajectories |

Sequence

prediction |

No

optimization feedback |

|

Pose

Forecasting |

Supervised

DL |

3D

joint angles |

Prediction

accuracy |

No

control mechanism |

|

Gesture

Synthesis Iqbal and

Sidhu (2022) |

Generative

DL |

Upper-body

joints |

Motion

realism |

Unstable

training |

|

Robotic

Motion |

DRL

(HRL) |

Kinematic

chains |

Skill

decomposition |

Complex

architecture |

|

Dance

Choreography |

Self-Supervised |

Pose

+ audio features |

Music–motion

alignment |

No

physical constraints |

|

Human

Balance Control Li et al.

(2021). |

DRL

(DDPG) |

COM

& joint states |

Stability

optimization |

Limited

aesthetics |

|

Expressive

Motion |

DRL

(SAC) |

Joint

+ style embeddings |

Expressiveness |

High

data demand |

|

Sports

Motion |

DRL

(PPO) |

Skeletal

+ force data |

Injury-safe

motion |

Domain-specific |

|

Dance

Pose Learning Xie et al.

(2021). |

DRL

+ MoCap |

Pose

sequences |

Pose

accuracy |

Weak

generalization |

|

Interactive

Avatars Ahir et al.

(2020). |

Actor–Critic |

Real-time

pose states |

Responsiveness |

Limited

complexity |

|

Dance

Pose Optimization |

PPO

/ SAC |

Joint

+ temporal + balance |

Multi-objective

optimization |

Scalability

& real-time limits |

3. Problem Formulation and Theoretical Framework

3.1. Formal definition of dance pose optimization as a Markov Decision Process (MDP)

Dance pose optimization is defined as Markov Decision Process (MDP) in order to represent the sequential and decision-making characteristic of human motion. An MDP can be defined as ⟨ 𝒮, 𝒜, 𝒫, acute, γ ∈ (0,1]) where distinctly 𝒮 is the state space, 𝒜 the action space, 𝒫 is the state transition dynamics, acute the reward function, and γ is the discount factor. In every discrete time t, the agent receives the current state s -n - of the dancer which is the pose and contextual motion information, and chooses an action a -n - of the dancer which is an action that alters the pose Izard et al. (2018). The dynamics of the environment then changes to a new state’s n 0 with probabilistic dynamics p(s n 0 | s n, a n) which represent biomechanical constraints and time continuity. The reward term ar(s n, a n, s n +1) represents several goals of interest to dance such as the accuracy of the poses against a reference, balance and smoothness of motion and energy efficiency. The agent is trained to maximize the expected cumulative discounted reward to learn a policy: π(a|s) that generates sequences of poses optimized over time as opposed to single frames Lugaresi et al. (2019). This formulation of MDP, especially in dance, is especially appropriate since it is inherently open to long-horizon optimization to enable the agent to take into account the future feasibility of poses and aesthetic flow. It is also through this theoretical framing that well-established DRA algorithms can be applied in order to have a principled foundation of learning adaptive and expressive policies to control dance pose.

3.2. State Space Representation (Joint Angles, Temporal Dynamics, Balance Metrics)

The state space is an important element in the dance pose optimization modelling since it determines the data that the learning agent possesses at a given time step. According to this, the state vector will be formulated to reflect instantaneous pose features as well as the time-varying context. Joint-level kinematic properties of the state (joint angles, angular velocities, relative limb orientations) are calculated on a skeletal model. These parameters have a compressed but expressive description of the pose configuration of the dancer in the present moment. The state is used to include motion history of stacked frames, velocity profiles or recurrent embeddings which condense recent pose transitions Grishchenko et al. (2022). This time data is necessary in motion continuity enforcement and avoiding sudden or unnatural variations of postures. In the absence of time, the actor can optimize single poses and generate sequences which are visually incoherent. Balance and stability signatures also enhance the state representation. These are center of mass projection, relationships of support polygons, joint torque estimates and indicators of symmetry. These characteristics enable the agent to make reasoning to determine whether the physical movements are feasible or not and to be in equilibrium in a dynamic movement. The state space allows the informed decision making by connecting the descriptors of kinematics, time, and the balance, which makes the biomechanical realism and the intent to express intersect.

3.3. Action Space Design for Pose Adjustment and Transition

The space of action characterizes the way the agent can affect the pose of the dancer in the time, and it is the main means of obtaining the smooth and manageable movement. Under the proposed framework, actions are represented as continuous valued modification to the joint parameters which may be incremental modification of the joint angles or the target joint velocities. Continuous spaces are better than discrete ones, because the moves in dancing are best viewed as fine-grained and within transitions that cannot be correctly represented by the crudity of action discretization. Action vectors describe synchronized changes in all the joints and allow the agent to learn to move the limbs in sync and not separately. In order to maintain biomechanical validity, action limits are place on anatomy-based limits of the joints, and the limits of the total angular velocities. These bounds originate impractical or dangerous pose specifications and less exploration of impractical corners of the action area. In the case of pose transitions, the design that should be used should facilitate temporal smoothness, disliking acceleration or jerk.

4. Proposed Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework

4.1. Overall system architecture for DRL-based dance pose optimization

The suggested Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework is structured in the form of a modular and end-to-end model, which combines the perception, decision-making, and motion execution in the process of dance pose optimization. It has a pose acquisition module as an initial part, which derives skeletal representations on motion capture data or vision-based pose estimation systems. Such skeletal characteristics will be converted into structured state vectors with description of joint kinematics, time context and balance related information. This information on the processed state is then inputted into the DRL agent which is the heart decision-maker. The DRA agent is used in an environment of simulation or physics-awareness which represents biomechanical limitations and temporal pose dynamics. The environment reacts by taking control actions generated by the agent each time step by changing the joint configurations, and the environment then responds by changing the pose and providing a reward signal. Multi-objective feedback is calculated by using a reward evaluation module that uses pose accuracy, stability, smoothness and energy efficiency. This feedback loop interaction is maintained among long sequences, which allows to optimize dance movements at long horizons.

4.2. Policy and Value Network Design (DQN, PPO, SAC, or Actor–Critic Variants)

The learning foundation of the proposed DRL framework is made up of the policy and value networks. Various network architectures are used depending on the action space formulation. To compute the action-value functions, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) are applied to the discrete or quantized pose adjustments to allow the agent to choose pose adjustments with the maximum expected return. Nevertheless, the nature of the dance movements is continuous, and therefore, the policy-gradient-based approaches are better. PPO uses an actor-critic architecture, in which the actor network provides a stochastic policy of continuous actions, and the critic network computes numbers of the state. The concept of Soft Actor Critic (SAC) is also expounded to promote effective exploration by maximizing the expected reward and the policy entropy which is favourable to finding a variety of expressive movement patterns. The networks are usually 100 percent connected networks extended by time encoders like LSTM or temporal convolution units in order to include dynamics of motion.

5. Learning Strategy and Optimization Process

5.1. Exploration–exploitation mechanisms in dance pose learning

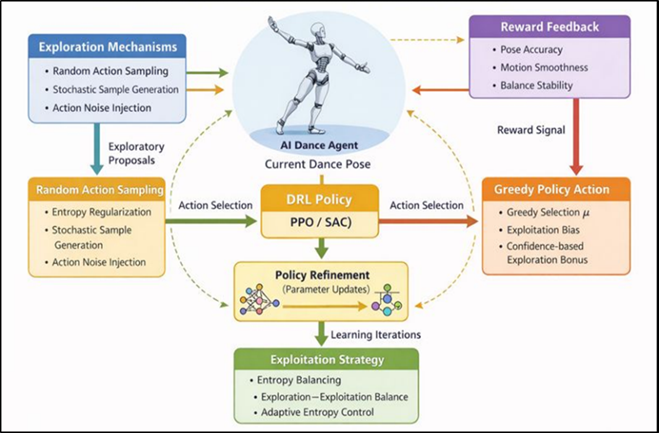

The exploration and exploitation must be balanced in learning the high-quality dance pose control policies since the agent should find a variety of possible movement strategies and gradually improve the best behaviors. The exploration methods that are promoted in the proposed framework are stochastic policy representations and entropy-based regularization, especially when policy-gradient algorithms like PPO and SAC are utilized. These processes enable the agent to explore a broad set of pose variations when learning very early in the training process such that it can discover both expressive and non-obvious movement patterns that might be absent in reference data. Figure 2 illustrates exploration exploitation architecture trade-off between policy learning, policy stability, and policy motion diversity.

As learning continues to advance, the structure is slowly converted to exploitation as it minimizes exploration noises and narrows policy distributions. This shift allows the agent to unify the learned behaviors and produce stable aesthetically coherent poses again and again. Sample efficiency is further enhanced by using experience replay and mini-batch updates that enable the agent to re-use informative transitions as well as prevents the agent to be prematurely drawn to suboptimal movement strategies. Biomechanical restrictions and action limits to the space of admissible pose adjustments allow preventing excessive and unsafe exploration.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Architecture of Exploration–Exploitation Mechanisms in DRL-Based Dance Pose Learning

5.2. Curriculum Learning for Progressive Pose Complexity

Learning of curriculum is also utilized to deal with the complexity character of the dance movements as well as in stabilizing the training of deep reinforcement learning agents. The agent is not presented to full body highly dynamic dance sequences immediately, but rather to simple tasks in the beginning of the learning process. Preliminary training levels concentrate on poses that are standing or even semi-standing and do not have a great number of joints and temporal fluctuation. This helps the agent to gain fundamental balance control and coordination of the joint without having to deal with high-dimensional dynamics. The more advanced the performance, the more pose complexity is gradually introduced into the curriculum, such as more joints, more extensive range of motions and more time-dependent Ness. Dynamism, rhythmic movements, partial choreography parts are gradually introduced, which promotes the agent to generalise acquired skills to a variety of movement patterns. The degree of difficulty in the tasks is also modified dynamically depending on the performance levels such that the agent only progresses when he develops adequate competence in each stage. This planned learning approach makes convergence less unstable and fast by matching task demand and the changing abilities of the agent.

5.3. Reward Shaping and Multi-Objective Optimization

The design of rewards is central to directing the learning process with meaningful maximization of outcomes of a dance pose. The suggested framework utilizes the concept of reward shaping which breaks the overall goal down into decipherable units all of which are relevant to a particular aspect of dance quality. These elements are relative precision of the pose to a reference or target pose, the smoothness of temporal change between poses, stability in balancing and energy efficiency. Reward shaping facilitates learning and reduces sparse reward problems that are usually faced in long-horizon problems by giving intermediate feedback. Multi-objective optimization is obtained by assigning weights to individual terms of the reward to indicate their relative weight. As an example, the reward of stability and safety is considered during the initial training and after an agent grows, the rewards of aesthetics and expressiveness are more considered. Adaptive weighting schemes also enable the reward system to change with time, such that optimization objectives are in step with curriculum development. Regularization terms are also included in an attempt to penalize unnatural joint movements, undue acceleration or even anisotropy.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6.1. Scalability to full-body, long-sequence choreography

Although the suggested framework of the deep reinforcement learning proves to be effective in terms of dance pose optimization, it is important to note that extending the framework to full-body and full-sequence choreography is a challenge. The number of joints and degrees of freedom increases and the state and action space expand defeating the convergence rate and enhancing the complexity of computation. The use of long choreography sequences also create a problem in assigning temporal credit, in which the effect of early choices in the pose may not be realized until well into the sequence. This complicates learning of policy and leads to the possibility of unstable training. Also, prolonged dance moves are commonly associated with the stylistic variations, change of direction, and switching between movement motifs. The hierarchical or modular reinforcement learning architectures might need to capture such diversity in one policy and add more design complexity. The existing models also can be unable to uphold long-term aesthetic integrity, because local pose optimization does not necessarily imply globally consistent choreography.

6.2. Real-Time Deployment Challenges and Latency Constraints

The practical limitation of real-time deployment of DRL-based systems that perform optimisation in dance pose is associated with the latency, computational cost, and system responsiveness. Latencies even as small as these may interfere with the natural movement flow and decrease the usefulness of these systems in form of real-time feedback. The second difficulty is occasioned by the necessity of precise and low-latency identification of poses. The problem of noise, occlusions or frame drop may be experienced in vision-based pose tracking systems, and this can propagate the error into the reinforcement learning policy. Of great importance to real-world application is ensuring that it will not be affected by such uncertainties. Moreover, running models on edge devices or wearable platforms is a very demanding task in terms of memory and power consumption.

6.3. Extension to Multimodal Feedback (Music, Emotion, Rhythm)

A significant weakness of the existing framework is that it mainly emphasizes the notion of kinematic optimization, and pays little attention to the multimodal environment of the context of dance. Dance movements are closely connected with music, rhythm, expression and these elements cannot be completely represented using solely the pose-based state representations and reward functions. Consequently, the optimized poses can be technically accurate, but not expressive in a way that they correspond to musical form or emotional purpose. Multimodal feedbacks also come with added problems, namely, representation and synchronization of heterogeneous data streams like audio features, beat structure, and affective cues. To implement these modalities into the framework of the reinforcement learning, significant attention should be paid to the design of the states and rewards in order to guarantee that movement and the external stimuli are meaningfully correlated. The way forward in future study is the use of multimodal reinforcement learning methods that would combine motion, audio, and affective cues. Emotion-sensitive reward and rhythm-consistent time limits might promote more expressive movements and time-consistent musical movements

7. Results and Performance Analysis

7.1. Quantitative performance comparison across DRL models

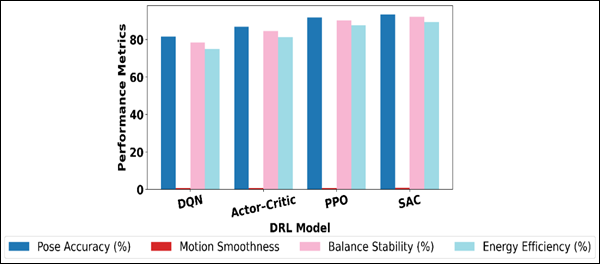

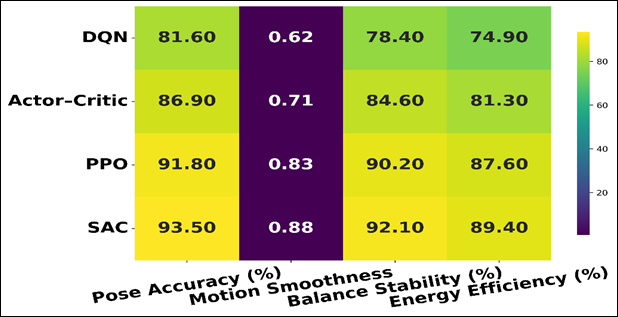

There was quantitative assessment to determine the performance of various DRL methods such as DQN, PPO, SAC, and Actor Critic variants on the optimization of dance poses. Measures like accuracy of poses, balance stability, smoothness of motion and cumulative reward were measured. The policy-gradient-based approaches always performed better than the value-based ones as PPO and SAC converged faster and obtained higher final rewards. SAC proved to be more efficient in exploration, resulting in an easier transition and higher energy efficiency and PPO showed more consistent training behaviour when trained in varying initialize conditions.

Table 2

|

Table

2 Comparative Performance of DRL Models for Dance

Pose Optimization |

||||

|

DRL

Model |

Pose

Accuracy (%) |

Motion

Smoothness Score |

Balance

Stability (%) |

Energy

Efficiency (%) |

|

DQN |

81.6 |

0.62 |

78.4 |

74.9 |

|

Actor–Critic |

86.9 |

0.71 |

84.6 |

81.3 |

|

PPO |

91.8 |

0.83 |

90.2 |

87.6 |

|

SAC |

93.5 |

0.88 |

92.1 |

89.4 |

Table 2 is a comparative quantitative analysis of four deep reinforcement learning models DQN, ActorCritic, PPO, and SAC trained on the optimization of dance poses to dance on a variety of performance aspects. The findings show that there is a definite hierarchy in the performance based on the appropriateness of each algorithm in the continuous control tasks.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparison of DRL Model Performance Metrics

DQN has the lowest scores on all of these metrics, with pose accuracy of 81.6% and motion smoothness of 0.62, indicating that it has a weakness in operating on continuous, high-dimensional action spaces, which are common to human dance movements.

Figure 4

Figure 4 DRL Model Performance Across Control Dimensions

There is a modest increase in the Actor-Critic model, with 86.9% pose accuracy and improved balance of 84.6% of the times, which shows the advantage of policy-value separation in the learning of coordinated motion patterns. PPO further increases performance to 91.8% pose accuracy and smoothness score of 0.83, which implies that the learning becomes more stable and the transition of poses is more constant.

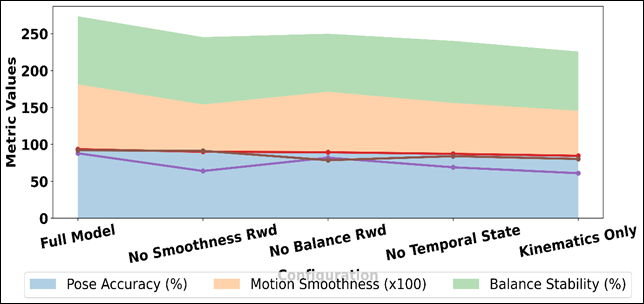

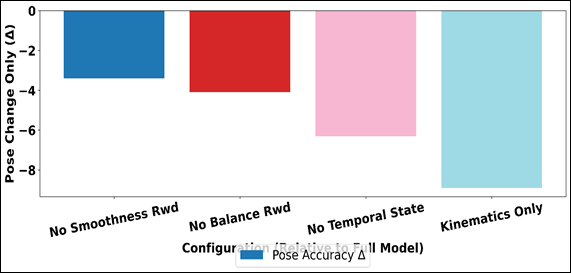

7.2. Ablation Study on Reward Components and State Representations

A study that ablated components of rewards and design of the state representation was conducted to determine the effect of these two on the performance of learning. The removal of temporal smoothness rewards caused sharp changes of poses and a lack of motion coherence, although the poses remained accurate. Omission of balance-related rewards led to shaky and physically unsustainable postures. In the same manner, state representations that were simplified and did not have time context also resulted in a performance drop since the agent could not foresee future pose feasibility. On the contrary, the addition of balance measures and motion history was a significant enhancement of the stability and visual quality. The results of these studies indicate that well designed rewards and rich representations of state are vital to obtaining strong, expressive, and physically sound optimization of dance poses with the help of DRL.

Table 3

|

Table

3 Impact of Reward and State Ablations on

Performance |

|||

|

Configuration |

Pose

Accuracy (%) |

Motion

Smoothness Score |

Balance

Stability (%) |

|

Full

Model (All Components) |

93.5 |

0.88 |

92.1 |

|

Without

Smoothness Reward |

90.1 |

0.64 |

91.3 |

|

Without

Balance Reward |

89.4 |

0.82 |

78.6 |

|

Without

Temporal State Features |

87.2 |

0.69 |

84.1 |

|

Kinematics-Only

State |

84.6 |

0.61 |

80.3 |

Table 3 evaluates the effects of reward design and representation of the state selection on the performance of the suggested DRL framework to optimize dance poses. The complete model, a model that integrates all elements of the rewards and rich state features, shows the highest overall performance where the pose accuracy value is 93.5, motion smoothness of the model is 0.88, and balance stability of the model is 92.1.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Ablation Analysis: Area Graph of Pose, Smoothness, and Balance Across Configurations

The effectiveness of simultaneous modelling of kinematic, temporal, and balance-related data in a multi-objective reward framework was proven by these results. Figure 5 illustrates the effect of components on pose accuracy, smoothness and balance stability Eliminating the smoothness reward causes a significant loss of motion smoothness, which drops to 0.64, but pose accuracy does not substantially decrease. Relative performance degradation is indicated in figure 6 in the presence of deletion of key elements of DRL. This shows that the smooth transitions do not automatically follow and have to be encouraged with the help of incentives.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Plot of Performance Drop Relative to Full DRL Model

Omitting the balance reward leads to a very large decrease in the balance stability to 78.6, even though the smoothness score is not very low, which again demonstrates the importance of stability-conscious rewards in physically realistic dance movements. The lack of features of temporal states also further reduces the performance, making pose accuracy only 87.2% and smoothness decreased, which proves the significance of motion history in anticipatory control.

8. Conclusion

In this work, we introduced a fully developed Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) model of optimization of dance poses, including the multifaceted nature of the interaction between the biomechanical and the temporal and the artistic expressiveness. Developed as a Markov Decision Process of the optimization of the dance poses, the proposed solution allowed the sequential decision-making process that considers long-horizon dependencies and cumulative quality of movements instead of individual pose accuracy. The combination of joint-level kinematics, time dynamics, and balance metrics in the state space presented an informative and rich representation of state space learning of stable and expressive control policies. By using a systemic analysis of the various DRL protocols such as DQN, PPO, SAC, and the actor-critic variants, the outcomes established that policy-gradient-based frameworks are especially practical in continuous, high-dimensional optimization of the dance movements. Such models had better convergence stability, better pose transitions, and better balance control than value-based baselines. Reward shaping and multi-objective optimization was essential in matching the learning goals with both technical and aesthetic movements attributes, and curriculum learning was important in enhancing training stability and scalability as the complexity of poses is increased. The proposed framework also highly considered the need to combine the pose estimation outputs with kinematic constraints to make them physically possible and safe. This constraint-sensitive learning approach eliminated impracticable motion artifacts as well as enabled the production of human like dances that could be used in practice. Scalability, real-time deployment and multimodal expressiveness issues are still there despite these advancements, making significant future research directions.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ahir, K., Govani, K., Gajera, R., and Shah, M. (2020). Application

on Virtual Reality for Enhanced Education Learning, Military Training and

Sports. Augmented Human Research, 5, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41133-020-00017-4

Chan,

J. C. P., Leung, H., Tang, J. K. T., and Komura, T. (2011). A Virtual

Reality Dance Training System Using Motion Capture Technology. IEEE

Transactions on Learning Technologies, 4, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2010.27

Choi, J.-H., Lee, J.-J., and Nasridinov, A. (2021). Dance Self-Learning Application and Its Dance Pose Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing

Davis, S., Thomson, K. M., Zonneveld, K. L. M., Vause, T. C., Passalent,

M., Bajcar, N., and Sureshkumar, B. (2023). An Evaluation of Virtual

Training for Teaching Dance Instructors to Implement a Behavioral Coaching

Package. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00732-3

Dias Pereira Dos Santos, A., Loke, L., Yacef, K., and Martinez-Maldonado,

R. (2022). Enriching Teachers’ Assessments of Rhythmic Forró Dance

Skills by Modelling Motion Sensor Data. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 161, Article 102776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102776

Esaki, K., and Nagao, K. (2023). VR Dance Training System Capable of Human Motion Tracking and Automatic Dance Evaluation. PRESENCE: Virtual and Augmented Reality, 31, 23–45.

Grishchenko, I., Bazarevsky, V., Zanfir, A., Bazavan, E. G., Zanfir, M., Yee, R., Raveendran, K., Zhdanovich, M., Grundmann, M., and Sminchisescu, C. (2022). BlazePose GHUM Holistic: Real-Time 3D Human Landmarks and Pose Estimation.

Guo, H., Zou, S., Xu, Y., Yang, H., Wang, J., Zhang, H., and Chen, W.

(2022). DanceVis: Toward Better Understanding of Online Cheer and Dance

Training. Journal of Visualization, 25, 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12650-021-00763-2

Iqbal, J., and Sidhu, M. S. (2022). Acceptance of Dance Training

System Based on Augmented Reality and Technology Acceptance Model (TAM).

Virtual Reality, 26, 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-021-00545-7

Izard, S. G., Juanes, J. A., García Peñalvo, F. J., Estella, J. M. G.,

Ledesma, M. J. S., and Ruisoto, P. (2018). Virtual Reality as an

Educational and Training Tool for Medicine. Journal of Medical Systems, 42,

Article 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-018-0900-2

Jin, Y., Suzuki, G., and Shioya, H. (2022). Detecting and

Visualizing Stops in Dance Training by Neural Network Based on Velocity and

Acceleration. Sensors, 22, Article 5402. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22145402

Lei,

Y., Li, X., and Chen, Y. J. (2022). Dance Evaluation Based on Movement

and Neural Network. Journal of Mathematics, 2022, Article 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3149012

Li,

D., Yi, C., and Gu, Y. (2021). Research on College Physical Education

and Sports Training Based on Virtual Reality Technology. Mathematical Problems

in Engineering, 2021, Article 6625529. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6625529

Lugaresi, C., Tang, J., Nash, H., McClanahan, C., Uboweja, E., Hays, M., Zhang, F., Chang, C.-L., Yong, M. G., Lee, J., et al. (2019). MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines.

Xie, B., Liu, H., Alghofaili, R., Zhang, Y., Jiang, Y., Lobo, F. D., Li,

C., Li, W., Huang, H., Akdere, M., et al. (2021). A Review on Virtual

Reality Skill Training Applications. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2, Article

645153. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2021.645153

Zhai, X. (2021). Dance Movement Recognition Based on Feature Expression and Attribute Mining. Complexity, 2021, Article 9935900. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9935900

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.