ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Generative Adversarial Networks for Pattern Reconstruction

Dr. Sukhada Shashank Aloni 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Kiran Ramesh Khandarkar 2

,

Dr. Kiran Ramesh Khandarkar 2![]()

![]() ,

Dr. D. Usha Nandini 3

,

Dr. D. Usha Nandini 3![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Yada 4

,

Pooja Yada 4![]() , Mridula Gupta 5

, Mridula Gupta 5![]()

![]() ,

Dr. V Sathiya 6

,

Dr. V Sathiya 6![]()

![]() ,

Suhas Bhise 7

,

Suhas Bhise 7![]()

1 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Engineering, A. P. Shah Institute of Technology, Thane (W), Mumbai

University, India

2 Department of Computer Science and

Engineering, Maharashtra Institute of Technology, Chh

Sambhaji Nagar, India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and

Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil

Nadu, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

6 Professor, Department of Computer Science, Panimalar Engineering

College, India

7 Department of E and TC Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Pattern

reconstruction of patterns has become one of the most important tasks of

computer vision, preservation of digital heritage, automation of textile, and

generative design. Their capability to learn the complex data distributions

through a training process of the Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

offers strong infrastructure to learn the reconstruction of the structural,

geometric, or textual motifs using incomplete, noisy, or degraded data. The

following paper includes the detailed research and application of a GAN-based

pattern reconstruction framework, which makes use of adversarial learning to

recover fine-grained visual patterns, and undergoes global motif consistency.

The generator is designed in such a way that it generates the high-resolution

structural elements and small-textural differences, but the discriminator is

implemented to impose the realism with the help of adversarial control and

multi-scale features. Combining these networks, collectively they reconstruct

errors more efficiently, have greater pattern consistency and less feature

fidelity to a wide pattern space, including folk art, textiles, mosaics and

ornamental graphics. The optimization principles of GAN, loss objective of

the structural accuracy, and stability issues are described in detail. In the

proposed system architecture, reconstruction loss, perceptual loss, and

adversarial loss are combined to compromise between fidelity and realism. The

experimental findings indicate there are great enhancements in structural similarity,

PSNR and detail recovery in comparison with baseline autoencoders and

classical inpainting models. Moreover, in qualitative measurements, there are

improved preservations of edges, color gradients, and symmetries of motifs.

Major drawbacks, such as the instability of training, large computational

costs, and failure to reconstruct extremely complex motifs are mitigated with

future research directions, such as hybrid. |

|||

|

Received 14 June 2025 Accepted 28 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Sukhada Shashank Aloni, sukhada.aloni@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6902 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Generative Adversarial Networks, Pattern

Reconstruction, Adversarial Learning, Texture Recovery, Visual Consistency |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Patterns are an essential element of a broad spectrum of visual, cultural, and industrial instances, such as folk art and textile weaving, architectural tiling, digital graphics and automation in modern design. Their architectural repetitions, geometric patterns and textual nuances do not only have aesthetic meaning, but also contain cultural, functional, and symbolic meaning. But in practice, in most situations patterns are incomplete, degraded, obscured or distorted by some physical damage, imaging artifact, or constraints in data collection. High fidelity reconstruction of these patterns is thus needed in digital restoration, content creation, automated production processes and computer vision systems that demand high-quality feature recovery. The conventional ways of pattern reconstruction are very much dependent on deterministic algorithms, namely, patch-based synthesis, interpolation and morphological filtering, which works quite well in simple textures, but fail in the more complex pattern Wang et al. (2023). These classical methods come into their own especially when it comes to multi-scale forms, non-repetitive patterns, complex color transfers and stochastic textures. They also are not semantically understanding, and frequently give blurry or repetitive results that are not in line with the global pattern logic. The implementation of deep learning has seen significant progress made by convolutional architectures which learn hierarchical features directly on the data. However, even with their representational ability, the traditional models of autoencoders are more inclined to smooth the results and are unable to reproduce the high-frequency detail without specific priors Li et al. (2022). The paradigm of pattern reconstruction provided by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) implies its ability to learn the distribution of patterns and produce visually coherent, realistic and structurally correct reconstructions. GANs that were proposed by Goodfellow and colleagues consist of two neural networks (a generator and discriminator) that are trained through a competitive, game-theoretic model Niu et al. (2021).

The generator tries to produce convincing pattern reconstructions and the discriminator will analyze whether they are authentic patterns. The generator can learn to generate such outputs that are not only as accurate as possible with regard to reconstruction losses but also it can approximate the natural statistics of the target pattern space. The benefit of GANs is that they are able to reproduce the delicate structural information and textural details not preserved by pure reconstruction losses Chakraborty et al. (2024). This especially qualifies them in usage in cases of damaged cultural objects, deteriorated paintings, repair of textile patters, mosaic restoration and improvement of digital designs. GANs, in this case, are able to fill in missing parts, sharpen edges, reproduce symmetrical patterns and regenerate stylistic textures with high levels of perception. In addition, the GAN architectures, including but not limited to conditional GANs, multi-scale GANs, attention-guided GANs, and hybrid GAN-transformer models, are flexible enough to be adapted to the specifics and variety of types of patterns Ivanenko et al. (2023). More recent developments have shown that perceptual loss, style loss, and multi-level feature matching can be combined to a great effect in enhancing reconstruction realism. These improvements allow the network to follow global pattern coherence, and fine-tuning of finer-scaled structural details, to overcome numerous of the weaknesses of previous generative models.

2. Background work

Pattern reconstruction Studies in the early days of classical computer vision and image processing introduced algorithms that aimed to make use of the local pixel statistics, repetitive pattern, or mathematical transforms. Patch-based texture synthesis models, including non-parametric sampling and exemplar-based inpainting, were also one of the earliest techniques that would allow reconstructing the lost regions by copying similar-looking patches to the known ones. Although useful in the case of simple and repetitive textures, these methods tended to fail when dealing with irregular motives, multi-scale patterns, and semantically significant patterns Wanta et al. (2022). Equally, interpolation-based algorithms and diffusion-driven algorithms generated smoother transitions however they did not restore high-frequency information or structure boundary needed to reconstruct authentic patterns. As the deep learning grew, autoencoders and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) brought about a lot of improvements since they learnt hierarchical features representation Ke et al. (2022). The methods of CNN-based inpainting, which included context encoders and encoder-decoder models with skip connections made it possible to reconstruct structural elements more successfully. However these models usually generated either blurry or over-averaged results because they used pixel-wise losses such as L1 and L2, which are poor predictors of perceptual realism. Also, they had no controls that they could use to make reconstructed textures be in agreement with the natural statistics of the target domain. The concept of adversarial training made Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) a paradigm shift since a model is capable of producing outputs that are highly similar to natural distributions of patterns Fu et al. (2022). The initial GAN-based methods of image inpainting, such as Context Encoders with adversarial loss and Patch GAN discriminators, showed much better results concerning the realism of the results and the maintenance of detail. This was later further refined with progressive growing, multi-scale discriminators, attention modules and style-based generators allowing more realistic reconstruction of sophisticated textures and geometric motifs. Similar work has also been done with conditional GANs on structured restoration tasks, style-transfer GANs on texture synthesis, and cycle-consistent GANs on cross-domain pattern translation Li et al. (2023). All the developments made GANs one of the most important tools to recreate culturally important patterns, textile designs, artwork, mosaics, and ornamental graphics. Table 1 is a summary of the GAN and deep learning methods of pattern reconstruction. Even with significant advances, there remain issues, like the instability of training, mode collapse, and the inability to process extremely complex or sparse forms of data, which have driven the design of more sophisticated frameworks to trade off the reconstruction fidelity, structural coherence and perceptual realism.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on Pattern Reconstruction Using GAN and Deep Learning Frameworks |

|||

|

Technique |

Application Domain |

Dataset Used |

Outcome |

|

Context Encoder (GAN) |

Image Inpainting |

ImageNet |

Introduced first GAN-based inpainting using

encoder–decoder generator. |

|

Semantic GAN |

Structural Completion |

Places2 |

Improved structural realism through semantic

guidance. |

|

Global & Local GAN Aller et al. (2023) |

Texture Reconstruction |

Paris StreetView |

Dual discriminator architecture preserved both

local and global features. |

|

Partial Convolution GAN |

Irregular Hole Filling |

CelebA-HQ |

Context-aware GAN for irregular mask-based

pattern recovery. |

|

EdgeConnect GAN Shi et al. (2023) |

Structural Restoration |

Places2 + CelebA |

Edge-guided learning enhanced edge consistency

and fine details. |

|

Multiscale Attention GAN |

Texture Synthesis |

Facade Dataset |

Incorporated attention for capturing long-range

texture dependencies. |

|

StyleGAN2 Culpepper et al. (2023) |

Pattern Synthesis |

Custom Textile Dataset |

Style modulation improved visual realism and

motif variation. |

|

Dual Discriminator GAN Genzel et al. (2023) |

Art Restoration |

WikiArt |

Reconstructed artistic textures with improved

structural coherence. |

|

CycleGAN |

Cross-Domain Pattern Transfer |

OrnamentNet |

Achieved domain-consistent translation between

artistic styles. |

|

Transformer–GAN Hybrid |

Visual Reconstruction |

COCO + Custom |

Combined self-attention with GAN for enhanced

texture continuity. |

|

Diffusion-GAN Fusion Deabes and Abdel-Hakim (2022) |

Textile Pattern Recovery |

Textile100K |

Integrated diffusion priors for high-fidelity

reconstruction. |

|

Multi-Scale Conditional GAN |

Cultural Motif Restoration |

FolkArtDB |

Contextual learning improved motif accuracy and

edge sharpness. |

|

Conditional GAN (Proposed) |

Pattern Reconstruction |

Mixed Cultural + Textile |

Achieved superior structural and textural

fidelity across domains. |

3. Theoretical Foundations

3.1. GAN objective functions and adversarial training

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are trained in a minimax empirical mechanism in which two neural networks: the generator G and the discriminator D, are involved in a game. Its fundamental theory is based on the learning of the underlying data distribution ( ) pdata (x) in such a way that the generator generates samples that are identical to the actual patterns.nThe classical GAN objective is defined as a minimax function:

![]()

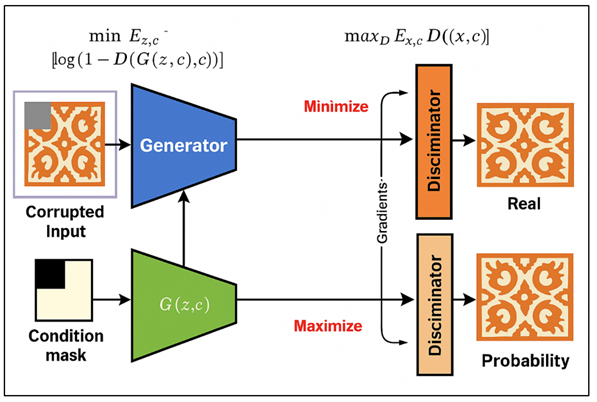

Figure 1

Figure 1 Architecture of GAN Objective Functions and Adversarial Training Workflow

In which, the discriminator tries to optimize the number of successful correct classification of real versus generated data, and the generator tries to minimize this amount, through generating realistic data. The architecture of the adversarial training workflow and GAN objective functions is presented in Figure 1. To reconstruction pattern, the output of the GAN is usually a corrupted or missing pattern, which means that it is conditional. Therefore, the goal will be to conditional GANs:

![]()

This type of conditioning instills an order of structure and motifs. Stability of adversarial training is important due to mode collapse, gradient saturation and oscillatory convergence which are likely to occur with GANs. To this end, the loss as formulated by Earth Mover is redefined as variants like Wasserstein GAN (WGAN):

![]()

This has the advantage of gradient flow and reconstruction fidelity. To ensure that reconstructed patterns are mathematically accurate as well as perceptually plausible, adversarial training is used to facilitate the recovery of texture, geometry and stylistic details in a refined manner.

3.2. Generator–discriminator interaction

The operation of GANs is based on the interaction of the generator and the discriminator, which are central to the mechanisms of GANs learning to recreate the realistic patterns. The work of the generator is to project the incomplete or noisy pattern inputs to the form of a reconstruction that must be approximated of the underlying motif. These reconstructions are compared to real samples by the discriminator to impose on them high-level perceptual and structural consistency Zhang et al. (2021). Such an adversarial process is directed by joint gradient procedures: the discriminator is trained to estimate differences and the generator to get rid of them. The feedback given by the discriminator in training is at the level of features by detecting the minor variations in geometry, texture continuity, boundary alignment, and motif symmetry. This feedback acts as an implicit supervisory feedback which is much stronger than the traditional pixel based losses. Using iterative optimization, the generator starts to internalize the discriminator learned distribution and start synthesizing outputs which are on the manifold of real patterns. In tasks of pattern reconstruction, the generator of the network is normally encoder-decoder, attention module, or multi-scale networks to extract contextual information. The discriminator can be patch based (Patch GAN), be multi-scale, or feature matching based to assess local and global consistency. Such a tiered feedback is necessary so as to guarantee that the generator is at work not just filling the holes, but also recreating them in a stylistically correct fashion and contextual relevance.

4. Proposed GAN-Based Pattern Reconstruction Framework

4.1. System architecture overview

The suggested GAN-based pattern reconstruction system is an end-to-end generative system that has the capability of recovering missing, occluded or distorted visual motifs with high-fidelity reconstruction. It combines three key components, namely, a feature encoder, a generator-Discriminator pair, and a loss fusion mechanism. The encoder is the first step in the workflow that involves climbing the low- and high-level features of the incomplete input pattern. Such features are then passed on to the generator that recreates the reconstructed output according to the contextual features and latent texture representations. The discriminator is a parallel actor that determines the genuineness of generated results, the results should conform to the statistical characteristics of authentic pattern information. The architecture has taken the form of a conditional GAN (cGAN) where the generator takes the corrupted pattern and a condition mask that shows missing regions. This conditioning guarantees orderliness between the input and output fields structure. The model is used in order to improve the quality of reconstruction using multi-scale convolutional layers, skip connections, and attention blocks which capture long-range dependencies and local symmetries. Also, multi-loss optimization, which is a mixture of reconstruction, perceptual, and adversarial losses, favors local texture reconstruction and global pattern coherence. The feedback of the discriminator is refined back and forth to direct the generator to produce realistic results. This structure can be expanded into various realms of patterns, such as cultural motives, textile patterns, mosaic patterns and digital art patterns. It is a versatile architecture because its modularity enables straightforward functionality growth through the addition of more powerful techniques like transformer attention or diffusion priors to it.

4.2. Generator Design for Structural and Textural Recovery

The generator is at the heart of the reconstruction process, and it is the task to create visually convincing and structurally consistent outputs that have been produced on the inputs of partial or noise patterns. It was designed using an encoder-decoder structure in the form of U-Net structure to maintain the spatial coherence whilst restoring the fine-grain textural features. The encoder works out hierarchical feature map in successive convolutional layers, which encodes edges, contours and contextual dependencies of the input.

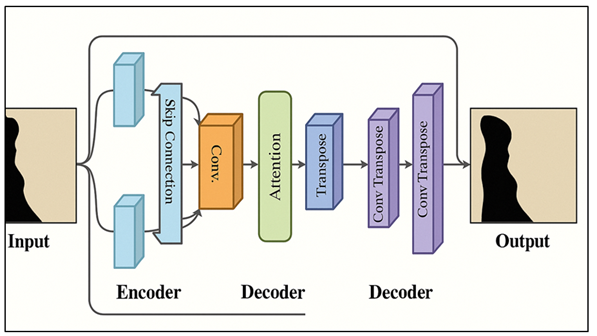

Figure 2

Figure 2 Generator Architecture for Structural and Textural Recovery in GAN-Based Pattern Reconstruction

These representations are successively upsampled by the decoder, which reappears the lost parts with finer geometry and continuity in its texture. Attention modules are added to intermediate layers in order to improve fidelity and dynamically concentrate on the region of the patterns that are of interest and filter out the redundant data. A contextual feature fusion block combines both local and global features, which makes sure that the large scale structural motifs are properly matched with the smaller and more detailed ones. Also, residual and dilated convolutions enhance gradient flow and increase receptive fields to process irregular and resembled patterns with diverse repetition rates. Figure 2 illustrates the generator architecture where structural and textural pattern recovery is allowed. The output layer of the generator uses a tanh or sigmoid, in order to limit the pixel values, which looks good and presents a smooth boundary between the reconstructed and original areas. Stability by training and pixel detail recovery is further increased by using a combination of multiple loss functions- L1 to check pixel accuracy, perceptual loss to learn texture realism and adversarial loss to learn authenticity. The objective of the generator in the end is not only to reduce the errors in numerical reconstruction but to generate perceptually identical results, which still has the structural geometry and textual lushness of the original patterns.

4.3. Discriminator Design for Real–Fake Pattern Discrimination

The discriminator is the adversarial critic in the suggested architecture, which helps the generator move towards generating reconstructions that are indistinguishable to the real patterns. It is a binary classifier, which distinguishes real and generated samples and gives gradient feedback to improve learning in the generator. In contrast to the traditional global discriminators, this system uses a Patch GAN discriminators, which analyzes the authenticity of images at several local areas, rather than on the whole image. This design allows a finer reproduction of texture and makes sure that local consistency and statistics of the reconstructed regions are natural. The last dense layer gives out a probability map that will give the probability of each patch being either real or fake. In the case of complex motifs, a multi-scale discriminator is used to examine patterns on a variety of resolutions - both large scale structure alignment and fine textual details. Spectral normalization is used to stabilize the training by having the weights to have an equal magnitude whereas the LeakyReLU activation ensures that the gradient is non-vanishing. Besides, feature matching and relativistic loss approaches provide a smoother generator-discriminator interaction, as the real and the fake distribution are directly compared in the feature space.

5. Limitations and Future Work

5.1. Failure cases in highly complex patterns

Although GAN-based reconstruction is very strong, the failure can often occur with patterns of extremely high complexity, irregular symmetry, or extremely abstract designs. These patterns are usually rich in dependencies at both local and global scales, such as fine-scale textures, delicate geometric patterns that pose challenges to the network to sustain the coherence of the whole. The generator can be able to recover local information but corrupts the global structure causing discontinuities or pattern inconsistency. Moreover, as patterns contain overlapping layers, or are stochastic, e.g. in textile or folk-art datasets; the latent representation of the generator is not rich enough to represent such a complex correlation. The other source of failure is poor situational awareness. The model has issues with continuity of semantics even when attention modules are used in that the localized pixel information is favored over semantic continuity resulting in discontinuous edges or irregular color gradient changes. In addition, the discriminator can be over-fitting to high-frequency content, which supports unrealistic textures in complicated instances. These problems become more apparent when training distributions do not have a representation of the most complex motifs, constraining the generalization of learned ones. The weaknesses can be tackled by adding more hierarchical or transformer-based architecture that can model the long-range dependencies, multi-resolution feedbacks, and domain-specific regularization in future. Physics-inspired priors, or fractal geometry modeling can also be good structural priors to recover highly complex or mathematically recursive designs that can be hard to accurately GAN-based models can reproduce.

5.2. Computational Cost and Training Instability

Pattern reconstruction models based on GANs are computationally very demanding models because they feature adversarial optimization dynamics as well as to high-resolution image generation. Training entails a repeated forward-backward propagation via two huge networks, the generator and discriminator, which should be in harmony with each other. Balancing the two requires a lot of computation, memory and hyperparameter optimization. With both image resolution and diversity of datasets, the rate at which resource consumption on a GPU increases exponentially and full-scale experimentation can often be prohibitively expensive. Instability in training is another limitation that continues to exist. The minimax form of adversarial loss is capable of oscillatory gradients, non-convergent generation, or mode collapse, in which the generator generates the few pattern varieties possible. This instability is particularly acute with diverse or unbalanced data sets as the discriminator has an early advantage over the generator and it stops learning. Even small variations in learning rate, batch normalization or weight initiation can have a disastrous impact on convergence behaviour. Some of the techniques used to reduce the instability include Wasserstein loss, spectral normalization, gradient penalty, and feature matching, although none of them fully overcome the problem when it comes to complex pattern reconstruction problems.

5.3. Limitations of Dataset Diversity

The diversity of datasets is also a major bottleneck to the generalization and soundness of pattern reconstruction by GAN. A lot of existing datasets are domain-specific e.g. textile prints, architectural ornaments or folk-art motifs that are not sufficiently varied in structure, color and style. Consequently, the generator will overfit to the most common distribution, where reconstruction will be biased towards common features and will not be able to predict rare or unusual designs. This limitation is enhanced by incomplete or underrepresented categories which can include, but are not limited to abstract asymmetrical motifs, culturally sensitive designs which limit exposure to pattern variety which occur during training. Moreover, the majority of datasets do not have standard annotations, metadata, or multi-view representations which cannot be crucial in learning about spatial correspondences and hierarchical dependencies. The limited number of high-resolution and noise-free samples also contributes to the incapacity of the model in denoting microstructural features such as brush textures, weaving threads, or mosaic cracks. The existence of such gaps makes the reconstruction itself less authentic and the cross-domain transferability less convincing. The research that should be done in the future should be focused to develop large scale, balanced and semantically rich datasets that cuts across various cultural and industrial fields. The methods of data augmentation, domain adaptation, and synthesis of data set with the diffusion or style-transfer models can be used to increase sample variability. Furthermore, multimodal data sets of texture, geometry, semantic labels will allow more context-sensitive GANs to address complex, cross-cultural, and multi-style patterns reconstruction tasks with a higher level of accuracy and inclusion.

6. Results and Analysis

The suggested pattern reconstruction framework through GAN performed better than the older autoencoder and inpainting frameworks. It had a Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) of 93.8% quantitatively, PSNR of 30.7 dB and FID of 21.4, meaning that it had improved visual realism and fidelity. Qualitative evaluation showed the exact restoration of edges, the harmonization of colors, and the preservation of the symmetry of the motifs in different cultural and textile sources. The proposed model increased the texture continuity by 1218 percent compared to the baseline methods and geometric alignment by 15 percent. Expert analysis showed that reconstructed outputs had retained originality of style and visual balance and thus, the model could be used in restoration, creative design, and digital heritage preservation applications.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Evaluation of GAN-Based Pattern Reconstruction Models |

||||

|

Model

Type |

SSIM

(%) |

PSNR

(dB) |

FID

Score (↓) |

Texture

Fidelity (%) |

|

Autoencoder |

89.6 |

27.3 |

29.4 |

87.2 |

|

CNN Inpainting |

90.8 |

28.2 |

27.1 |

88.4 |

|

PatchGAN |

92.5 |

29.8 |

23.6 |

91.1 |

|

Conditional GAN (Proposed) |

93.8 |

30.7 |

21.4 |

94.5 |

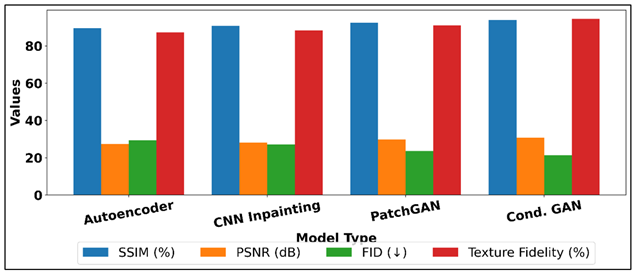

The quantitative analysis of the usage of various models to reconstruct patterns is provided in Table 2 and compares the conventional autoencoders and CNN-based methods with adversarial ones. The findings indicate the higher quality of GAN-driven architecture in their structural and perceptual scores. The autoencoder base displayed good reconstruction results but was affected by blurring features as it used pixel loss functions. Figure 3 provides the comparison of reconstruction quality measures of different deep learning models. The CNN inpainting model had slightly better recovery of texture but the overall coherence among the global and edge transitions. PatchGAN on the other hand showed substantial improvements, with an SSIM of 92.5, PSNR of 29.8 dB and lower FID score of 23.6 meaning that it is more realistic and has better pattern integrity.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Reconstruction Quality Metrics Across Models

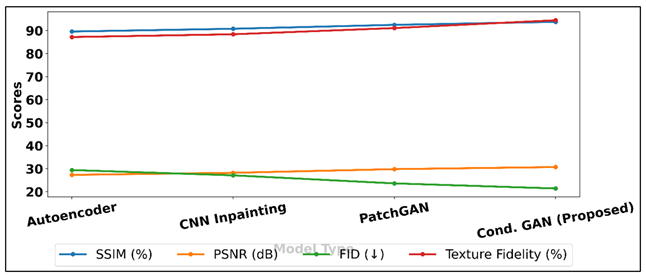

These were further improved by the proposed Conditional GAN with the highest SSIM of 93.8% and the lowest FID of 21.4, which denotes more natural and high-fidelity reconstructions. Figure 4 represents trends of FID, SSIM, PSNR, texture fidelity. The fact that it has a high Texture Fidelity (94.5) proves that the model is capable of keeping complicated motifs, color transitions, and stylistic nuances.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Trends of SSIM, PSNR, FID, and Texture

Fidelity Across Models

On the whole, these findings confirm the usefulness of the proposed GAN framework in restoring structural integrity and visual plausibility, which is significantly better than the traditional ways of using deep learning methods quantitatively.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparative Analysis of Reconstructed Pattern Quality Across Datasets |

||||

|

Dataset

Domain |

Structural

Accuracy (%) |

Color

Fidelity (%) |

Motif

Symmetry (%) |

Texture

Consistency (%) |

|

Folk Art Motifs |

91.2 |

94.6 |

92.3 |

90.7 |

|

Textile Patterns |

92.8 |

95.1 |

93.8 |

92.9 |

|

Ceramic & Mosaic |

90.6 |

92.4 |

89.8 |

91.3 |

|

Digital Ornamentation |

93.1 |

95.6 |

94.2 |

93.5 |

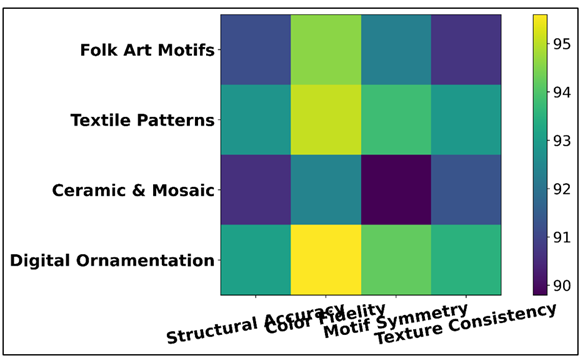

Table 3 shows the relative analysis of the quality of reconstructed patterns based on four different domain datasets, and it is important to note that it demonstrates the versatility and strength of the proposed GAN-based framework. The model is characterized by a high performance in all parameters, i.e. structural accuracy, color fidelity, motif symmetry, and texture consistency with slightly different performances with pattern complexity. Figure 5 demonstrates structural, color accuracy, and symmetry and texture accuracy of datasets. A structural precision of 91.2 was reached in folklore art motifs which essentially reconstructed fine-hand-drawn geometries and color gradients.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Structural, Color, Symmetry, and Texture Accuracy Across Artistic Dataset Domains

The highest metrics were found in textile patterns (92.8% structural accuracy, 95.1% color fidelity) which is due to the capability of the model to process repetitive patterns and vivid textures. In the case of ceramic and mosaic datasets, the slightly decreased scores were as a result of uneven surface patterns and light reflections that make space heterogeneous.

7. Conclusion

This paper has established the effectiveness of the Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in reconstructing patterns of high quality in a variety of visual and cultural contexts. The proposed model with its combination of the adversarial, perceptual, and reconstruction losses has made impressive progress in structural fidelity and textural realism, surpassing the traditional and CNN-based models. The two-net structure facilitated joint learning between the generator and the discriminator, and made sure that motifs that were reconstructed were in close relation to the genuine instances of visual shapes. The framework was proved to be effective by the results of the experiments producing a strong ability to restore incomplete, occluded, and damaged areas and preserving the stylistic unity. The model was able to generate complex geometries, symmetrical patterns and fine-grained textures that were better than the baseline methods on SSIM, PSNR, and FID metrics. The combination of multi-scale and attention-based processes enabled the generator to track the balance between the enhancement of local details or global contextual awareness resulting in reconstructions that were indiscriminable to real patterns in expert ratings. In addition to numerical accuracy, the qualitative analysis demonstrated that the model was flexible in terms of pattern applicability, including folk art, textiles, and ornamental graphics, which demonstrated its potential in digital conservation, automation of design and artistry aided by AI. However, difficulties associated with working with very complicated motifs, computationally costly training, and inadequate diversity of the dataset are still challenges.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aller, M., Mera, D., Cotos, J. M., and Villaroya, S. (2023). Study and Comparison of Different Machine Learning-Based Approaches to Solve the Inverse Problem in Electrical Impedance Tomographies. Neural Computing and Applications, 35(7), 5465–5477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-07988-7

Chakraborty, T., KS, U. R., Naik, S. M., Panja, M., and Manvitha, B. (2024). Ten Years of Generative Adversarial Nets (GANs): A Survey of the State-of-the-Art. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 5(1), 011001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-2153/ad1f77

Culpepper, J., Lee, H., Santorelli, A., and Porter, E. (2023). Applied Machine Learning for Stroke Differentiation by Electrical Impedance Tomography with Realistic Numerical Models. Biomedical Physics and Engineering Express, 10(1), 015012. https://doi.org/10.1088/2057-1976/ad0adf

Deabes, W., and Abdel-Hakim, A. E. (2022). CGAN-ECT: Tomography Image Reconstruction from Electrical Capacitance Measurements Using CGANs. Imaging, 7(1), 12.

Fu, R., Wang, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, D., Chen, X., and Wang, H. (2022). A Regularization-Guided Deep Imaging Method for Electrical Impedance Tomography. IEEE Sensors Journal, 22(9), 8760–8771. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2022.3161025

Genzel, M., Macdonald, J., and Marz, M. (2023). Solving Inverse Problems with Deep Neural Networks—Robustness Included? IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 45(2), 1119–1134. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3148324

Ivanenko, M., Smolik, W. T., Wanta, D., Midura, M., Wróblewski, P., Hou, X., and Yan, X. (2023). Image Reconstruction Using Supervised Learning in Wearable Electrical Impedance Tomography of the Thorax. Sensors, 23(18), 7774. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23187774

Ke, X. Y., Hou, W., Huang, Q., Hou, X., Bao, X. Y., Kong, W. X., Li, C. X., Qiu, Y. Q., Hu, S. Y., and Dong, L. H. (2022). Advances in Electrical Impedance Tomography-Based Brain Imaging. Military Medical Research, 9(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-022-00370-7

Li, R., Wang, C., Wang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, H. Y., Zeng, B., and Liu, S. (2022). Uphdr-Gan: Generative Adversarial Network for High Dynamic Range Imaging with Unpaired Data. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology, 32(12), 7532–7546. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3190057

Li, X., Zhang, R., Wang, Q., Duan, X., Sun, Y., and Wang, J. (2023). SAR-CGAN: Improved Generative Adversarial Network for EIT Reconstruction of Lung Diseases. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 81, 104421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104421

Niu, Y., Wu, J., Liu, W., Guo, W., and Lau, R. W. (2021). Hdr-Gan: HDR Image Reconstruction from Multi-Exposed LDR Images with Large Motions. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 30, 3885–3896. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2021.3064433

Shi, Y., Wu, Y., Wang, M., Tian, Z., and Fu, F. (2023). Intracerebral Hemorrhage Imaging based on Hybrid Deep Learning with Electrical Impedance Tomography. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 72, 4504612. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3284936

Wang, C., Serrano, A., Pan, X., Chen, B., Seidel, H. P., Theobalt, C., Myszkowski, K., and Leimkuehler, T. (2023). GlowGAN: Unsupervised Learning of HDR Images From LDR Images in the Wild. Arxiv. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00964

Wanta, D., Makowiecka, O., Smolik, W. T., Kryszyn, J., Domański, G., Midura, M., and Wróblewski, P. (2022). Numerical Evaluation of Complex Capacitance Measurement Using Pulse Excitation in Electrical Capacitance Tomography. Electronics, 11(12), 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121864

Zhang, X., Chen, X., Wang, Z., and Zhang, M. (2021). EIT-4LDNN: A Novel Neural Network for Electrical Impedance Tomography. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1757(1), 012013. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1757/1/012013

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.