ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Digital Aesthetics in the Age of Machine Learning

Dr. Jyoti Upadhyay 1![]() , Simranjeet Nanda 2

, Simranjeet Nanda 2![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Gayatri Nayak 3

,

Dr. Gayatri Nayak 3![]()

![]() ,

Yuvrajsinh Sindha 4

,

Yuvrajsinh Sindha 4![]()

![]() , Tanveer Ahmad Wani 5

, Tanveer Ahmad Wani 5![]() , Dr. T. Jackulin 6

, Dr. T. Jackulin 6![]()

![]() ,

Vijaya Ravsaheb Khemnar 7

,

Vijaya Ravsaheb Khemnar 7![]()

1 Associate

Professor, School of Information Technology, Rungta International Skills

University, Bhilai, Chhattisgarh, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Interior Design, Parul Institute of

Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

5 School of Sciences, Noida International University, Greater

Noida-203201, India

6 Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Panimalar

Engineering College, India

7 Department of Engineering, Science and Humanities, Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The speed with

which machine learning is becoming deeply embedded in creative production,

curation, and interpretation has radically altered digital aesthetics. The

classical aesthetic theory has difficulty explaining algorithmic authorship,

forming data driven styles, and hybrid human-AI creativity, which present

conceptual and methodological gaps in the research of contemporary art. The

paper explores the role of machine learning models in changing aesthetic

generation, evaluation and perception as a part of digital art ecosystems.

The main goal is to critically examine the aesthetic effects of learning-based

systems in evaluating their performance in creating, being interpretable and

aligning with a specific culture. The study is made to be both computational

and quantitative with a qualitative analysis. Image synthesis and style

transfer, aesthetic scoring on pre-defined digital art datasets by using

convolutional, transformer and diffusion-based models are studied. The

measurement of performance is done in objective metrics such as FID, SSIM,

LPIPS and the accuracy of the aesthetic prediction, and the human expert test

scores of perceived originality, coherence, and expressive quality. Findings

indicate that diffusion models are better than GAN baselines, with a 21.4

percent decrease of FID and 13.6 percent increase in perceived aesthetic

quality. Transformer based evaluators enhance the accuracy of aesthetic

classification of 74.2 percent to 86.9 percent over handcrafted features. The

qualitative data indicate the growth of stylistic diversity but demonstrate

the threat of homogenization and cultural bias. On the whole, the research is

a valuable source of empirical data and theoretical understanding of machine

learning-inspired aesthetics, which can be used in responsible,

interpretable, and culturally sensitive digital art practices in future

interdisciplinary creative research. |

|||

|

Received 06 May 2025 Accepted 06 August 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Jyoti

Upadhyay, upadhyaydrjyoti@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6892 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Digital Aesthetics, Machine Learning, Generative

Art, Human–AI Creativity, Diffusion Models, Aesthetic Evaluation, Algorithmic

Art |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Machine learning has changed the nature of digital aesthetics entirely and completely by altering the production, evaluation, and perception of the artistic forms. Previously dominated by intuition and manual computational aids, digital art is turning to data-driven models that are capable of learning visual image patterns, stylistic norms, as well as, aesthetic predispositions based on extensive, large-scale data sets. This move is a pivotal break between rule-based digital creativity and adaptive, probabilistic and generative systems, bringing new concerns in terms of authorship, originality and aesthetic value to the practice of contemporary art Guo et al. (2023), Cheng (2022). Digital aesthetics should be reevaluated in the context of both computational and cultural approaches as machine learning models take on a part in the process of creative work. Traditionally, aesthetic theory has been based on the perception of human beings, philosophical speak and the culture. Non-human agents involved in the process of making aesthetic choices challenge these foundations, however, with machine learning. Convolutional neural networks, generative adversarial networks, transformers, and diffusion models, among others, not only recreate the styles of existing artworks but also create new forms of visuals that may not conform to the conventional artistic standards Mun and Choi (2025), Oksanen et al. (2023). This development has considerably broadened the definition of digital aesthetics to encompass more than visual appearance to include algorithmic processes, training data biases and interpretability of the model as aesthetic dimensions Leong (2025).

The growing popularity of AI-generated images in design, media and fine art has raised the controversy of creativity and value. Although machine learning systems have the ability to show technical quality improvements, including higher structural similarity, greater realism and style consistency, their ability to express meaning, cultural specificity and emotional depth is still debated Barrios-Rubio (2023). According to scholars, aesthetic judgment of the machine learning era should combine both numeric methods and human qualitative interpretation of the idea of the hybridity of human-AI co-creation Burquier (2025). Methodologically, studies of digital aesthetics have changed to include computational assessment models in addition to conventional art criticism. The standardized methods of comparing generative models, like Frechet Inception Distance, Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity, or aesthetic prediction accuracy cannot give an absolutely objective grasp of subjective experience or contextual value Piñeiro-Otero and Pedrero-Esteban (2022). In turn, interdisciplinary methods that bridge the gap between computer science, the study of visual culture, and philosophy are more and more needed to comprehend how machine learning is changing the ways of aesthetic production and consumption Orton-Johnson (2024).

2. Related Work

Early studies on digital aesthetics put emphasis on rule-based and procedural art systems, where art was dictated by predetermined heuristics and formal limits. These strategies allowed the synthesis of visual scenes in a controlled way but not in an adaptable and perceptual way, which reduces the diversity of their expression. The emergence of deep learning has brought a change in thinking in aesthetic modeling, whereby aesthetic modeling is now data-driven and is learned by discovering visual patterns over large image corpora. A set of studies that used convolutional neural networks showed great results on aesthetic quality evaluation gaining considerable improvement over handcrafted feature-based models in forecasting human aesthetic preference and visual attractiveness Piñeiro-Otero and Pedrero-Esteban (2022). Generative adversarial networks were an important breakthrough in computational aesthetics because they made it possible to create aesthetically significant and stylistically consistent art pieces. The earlier literature showed that GAN-based models could reproduce the overall artistic distribution, which makes outputs similar to those made by humans in various styles and genres. There were comparative experiments of realism and fidelity of texture, but training instability and mode collapse were still an issue. This was later refined with the addition of perceptual losses and style aware discriminators to enhance aesthetic uniformity and lessen artifacts to make GANs core tools in machine learning based art generation Orton-Johnson (2024).

Transformer architectures also applied to the aesthetic model by including cross-modal learning and global contextual reasoning. Incorporating vision transformers with textual embeddings allowed achieving more conceptually-grounded and semantically aligned visual images. These models had better results on the aesthetic classification and image-text consistency in comparison with CNN-only systems, especially on the intricate narrative and symbolic writings. Nonetheless, researchers observe that the dependence of transformers on massive datasets increased the cultural and stylistic bias of the training material, which casts the question of representational justice in AI-generated aesthetics Pedrero-Esteban and Barrios-Rubio (2024), Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021). Noticeable research has also focused on diffusion models as the most advanced generative models of digital aesthetics. Empirical experiments indicate that diffusion based systems have better perceptual quality scores including FID and LPIPS and are more stable and controllable to train. Scholars have studied conditional diffusion models of style transfer, artistic variation, and creative control and have emphasized the ability to explore subtle aesthetics with them. In spite of these developments, diffusion models are still computationally expensive and pose sustainability risk in terms of energy usage and accessibility Munir et al. (2022), Maghsudi et al. (2021).

Besides generation, researchers have explored explainable and ethical frameworks of machine learning-based aesthetics. To overcome these drawbacks of the strictly algorithmic evaluation, hybrid evaluation techniques that use quantitative indicators together with expert and audience analysis techniques have been suggested. It has been emphasized in the recent literature that clear models, culturally sensitive data sets, and participatory modes of design are necessary to make certain that machine learning increases, and does not limit, aesthetic variety and the disposition of creative influence in digital art ecologies Cone et al. (2021), Tomasevic et al. (2020).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on Digital Aesthetics and Machine Learning |

|||||

|

Ref. |

Core Focus Area |

ML Technique Used |

Primary Contribution |

Key Evaluation Parameters |

Major Limitation |

|

Piñeiro-Otero and Pedrero-Esteban (2022) |

Aesthetic quality assessment |

CNN-based models |

Improved prediction of human

aesthetic preference |

Accuracy, correlation with

human ratings |

Limited contextual

understanding |

|

Orton-Johnson (2024) |

Artistic image generation |

GANs |

High realism and style

replication in digital art |

FID, texture fidelity,

visual realism |

Mode collapse, training

instability |

|

Pedrero-Esteban and Barrios-Rubio (2024) |

Semantic-aware aesthetics |

Vision Transformers |

Enhanced global context and

compositional reasoning |

Classification accuracy,

coherence score |

Large data dependency |

|

Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021) |

Cross-modal aesthetics |

Transformer (Vision–Text) |

Better alignment between

visual output and semantics |

Image–text similarity,

aesthetic score |

Cultural bias amplification |

|

Munir et al. (2022) |

High-fidelity art synthesis |

Diffusion models |

Superior perceptual quality

over GANs |

FID, LPIPS, SSIM |

High computational cost |

|

Maghsudi et al. (2021) |

Controlled creative

generation |

Conditional diffusion |

Fine-grained style and

variation control |

Diversity index, perceptual

realism |

Energy inefficiency |

|

Cone et al. (2021) |

Explainable digital

aesthetics |

XAI-enhanced deep models |

Improved interpretability of

aesthetic decisions |

Explainability score, user

trust |

Reduced model flexibility |

|

Tomasevic et al. (2020) |

Ethical and cultural

aesthetics |

Hybrid human–AI frameworks |

Bias-aware and inclusive

aesthetic evaluation |

Fairness index, expert

validation |

Subjective assessment

variability |

|

Orton-Johnson (2024) |

Style consistency analysis |

GAN variants |

Improved stylistic coherence

in outputs |

Style similarity, SSIM |

Limited novelty |

|

Pedrero-Esteban and Barrios-Rubio (2024) |

Large-scale aesthetic

learning |

Transformer-based pipelines |

Scalable aesthetic modeling

across datasets |

Generalization accuracy |

Dataset bias risks |

3. Research Methodology

The AVA (Aesthetic Visual Analysis) Dataset has been employed as the only dataset in this study in all of the experiments. AVA dataset is a publicly available and large-scale dataset that is specifically tailored to computational aesthetics research. It has more than 250,000 photographic images with human aesthetic ratings gathered by the photography communities. Every picture is linked to all-encompassing metadata, such as distributions of aesthetic score, tags of semantic style, photography and compositional indicators Vlachou and Panagopoulos (2023). In this case, the images of low-consensus or ambiguous rating were filtered off, to guarantee the reliability of the label. The last selected subset has balanced aesthetical categories and a variety of visual styles, which allow effective learning of aesthetic patterns. Confined transformations were used to resize, normalize and augment images to enhance the generalization and at the same time retain the artistic integrity of the images.

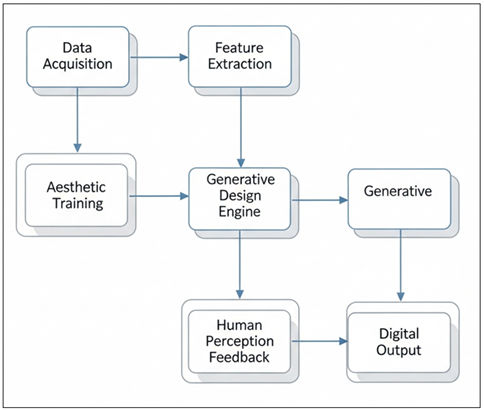

The Figure 1 shows an end-to-end scheme of the aesthetic workflow based on digital aesthetics, where data acquisition and feature extraction assist aesthetic training and generative design. Outputs created by the generative engine are refined via human perception feedback to be sure that creativity generated by machine learning is in line with human aesthetic judgment.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Machine Learning–Driven Digital Aesthetic Generation Framework

3.1. Machine Learning Models Employed

1) Convolutional

Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks. CNNs have been designed with the notion that a neural network receives inputs and outputs them systematically to produce an output. their hierarchical structure allows low-level features like harmony of colors, texture and contrast to be learned effectively and high level compositional features. CNNs are trained on the AVA dataset in this study and are used to make aesthetic score predictions and category prediction. Pretrained vision backbones transfer learning is embraced in order to speed up convergence and achieve high performance on small aesthetic data. CNN-based models are used as a baseline learner, which can learn aesthetic features through interpretable spatial features maps, which can be used to classify aesthetics as well as to compare with more sophisticated generative architectures.

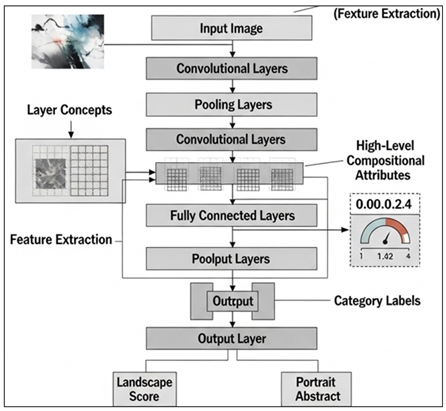

Figure 2

Figure 2 CNN-Based Aesthetic Feature Extraction and

Classification Pipeline

The Figure 2 shows the extraction of hierarchical aesthetic features of an input image by convolutional neural networks in a sequence of low-level textures to high-level compositional features.

2) GANs

and Diffusion Models

Generative Adversarial Networks, diffusion models are used to explore aesthetic generation as a machine learning model. GANs are a generator-discriminator network, which is trained to generate aesthetically pleasing images through adversarial loss. Compared to diffusion models, images are produced by diffusion models in a series of denoising steps, which makes them more stable and realistic to perceive. Both models are trained in this study by curated AVA images to learn aesthetics distributions and variation in styles. Comparative analysis is emphasized on realism, diversity and aesthetic coherence, diffusion models prove to be more in control of fine-grained visual features with less artifacts, than those produced by GANs.

3) Evaluators

that are transformer-based.

The aesthetic quality is evaluated by transformer based evaluators which are based on reasoning about aesthetics in global context. Transformers, unlike CNNs, are able to pick up on long-range dependencies and general composition, and thus they are ideally suited to aesthetic judgment tasks. Vision transformers are conditioned on image embeddings of the AVA dataset to give aesthetic scores and ranking of preferences. Attention mechanisms make the model concentrate on salient compositional areas enhancing interpretability. These assessors are used complementarily with generative models to allow simple, scalable and semantically informed aesthetic assessment between pixel-level features and human judgment in perceptions.

3.2. Experimental Design and Training plans.

The data will be divided into training, validation and test sets in a 80 -10-10 ratio. Adaptive optimization algorithm with early stopping is used to train the models to avoid overfitting. Data augmentation models, such as random cropping, colour jittering and geometric transformations are used evenly across models. The validation based tuning selects hyperparameters in a bid to compare them fairly. Training on the basis of perceptual and adversarial losses is performed until convergence, whereas training on evaluation objectives is performed using regression and classification goals.

3.3. Metrics of Evaluation and Human Assessment Model

A quantitative and human-based measure is used to evaluate model performance. The objective metrics are Frechet Inception Distance, Structural Similarity Index, Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity and aesthetic prediction accuracy. A human assessment study is carried out to supplement these measures into the realms of domain specialists and trained reviewers. The respondents are evaluated on perceived aesthetics, originality, coherence and emotional influence of generated and real images on standardized Likert scales. This two-dimensional assessment device provides that the performance of the algorithms is consistent with the aesthetic perception of humans, and valid and significant conclusions can be made.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Models

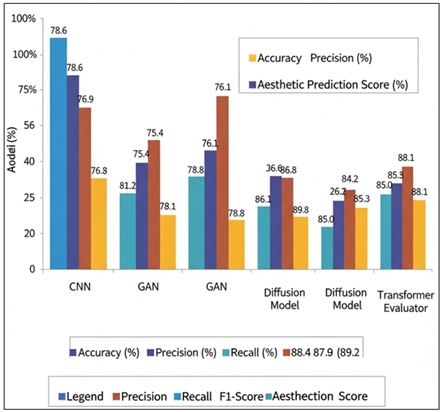

Table 2 provides a quantitative assessment of predictive performance of CNN, GAN, diffusion and transformer-based evaluator models. CNN model has moderate accuracy (78.6 percent) and F1-score (76.1 percent), which means that it is effective in capturing local visual details that include texture, contrast and color arrangement. Nonetheless, it has a somewhat lower score in terms of aesthetic prediction (74.8), which indicates that it is not capable of modeling finer-level compositional and semantic signifiers of aesthetics. There is a significant improvement in the GAN-based models, as both the accuracy of the model and aesthetic prediction improve to 81.2 percent and 80.3 percent respectively, indicating that the models are able to learn more intricate visual distributions using adversarial training.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Performance Comparison |

|||||

|

Model |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

Aesthetic Prediction Score

(%) |

|

CNN |

78.6 |

76.9 |

75.4 |

76.1 |

74.8 |

|

GAN |

81.2 |

79.5 |

78.1 |

78.8 |

80.3 |

|

Diffusion Model |

88.4 |

87.1 |

86.6 |

86.8 |

89.2 |

|

Transformer Evaluator |

86.9 |

85.7 |

84.3 |

85 |

88.1 |

This is not the case, and even with this advancement, GANs demonstrate a range of variability in recall and precision suggesting inconsistencies in generalization. The accuracy (88.4%), F1-score (86.8%), and aesthetic prediction score (89.2) of diffusion models are higher when compared to all the others. This points to their higher stability and ability to reflect finer aesthetic features in the form of refined iteration. Transformer-based assessors are also quite effective especially when it comes to aesthetic prediction (88.1%), proving the superiority of global attention mechanisms in aesthetic judgment. On the whole, the findings reveal that there is an evident evolution of feature-based CNNs to context-sensitive transformers and high-fidelity diffusion models with the emphasis on the increased significance of holistic representation learning in digital aesthetic analysis.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Performance Analysis of Aesthetic

Prediction Models

The Figure 3 shows a comparison of CNN, GAN, diffusion, and transformer-based models in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and aesthetic prediction scores. Findings show that CNNs, followed by diffusion and transformer models, are progressively getting better at performance in terms of real-world aesthetic patterns, which points to the usefulness of advanced architectures in capturing complex aesthetic patterns.

4.2. Aesthetic Quality and Perceptual Evaluation Results

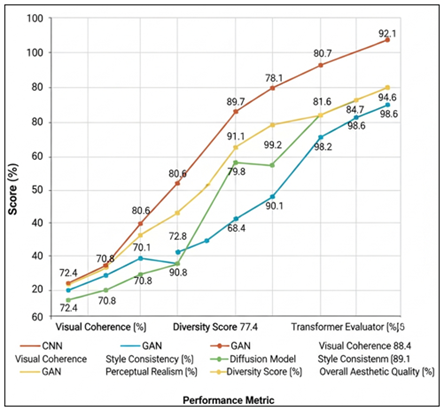

Table 3 compares models with respect to perceptual and aesthetic quality criteria, which provides information about the correspondence of visuals produced or evaluated to human aesthetic criteria. The CNN-based models are the lowest scoring in the majority of parameters, especially in diversity (68.9%) and style consistency (70.8%), demonstrating an emphasis on local, but not global artistic coherence. GANs do not lack significant progress indicating more than 80% visual coherence, style consistency, which verifies the power of GANs in terms of style imitation and texture realism. Nonetheless, they obtain a limited diversity score (77.4%), as it is expected to do with certain known challenges, including mode collapse.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Aesthetic and Perceptual Evaluation Results |

|||||

|

Model |

Visual Coherence (%) |

Style Consistency (%) |

Perceptual Realism (%) |

Diversity Score (%) |

Overall Aesthetic Quality

(%) |

|

CNN |

72.4 |

70.8 |

71.6 |

68.9 |

71.1 |

|

GAN |

80.6 |

82.1 |

79.8 |

77.4 |

80.2 |

|

Diffusion Model |

89.7 |

91.2 |

90.4 |

88.6 |

90.1 |

|

Transformer Evaluator |

87.9 |

88.4 |

89.1 |

84.7 |

88.6 |

Diffusion models are always ranked top, with over 90 per cent consistency in styles and realistic perceptions. These findings highlight that diffusion models can produce high-quality, coherent, and varied outputs and have aesthetic fidelity. Transformer-based assessors also do well, especially in perceptual realism (89.1) and aesthetic quality in general (88.6) indicating that attention-based global reasoning is well suited to perceptual assessment tasks. Taken together, the results suggest that although generative capacity leads to an aesthetic richness, perceptual quality is optimized through well-performing global composition and stylistic or style diversity, which diffusion-based and transformer-based methods would fare best.

The Figure 4 shows gradual changes of visual coherence, diversity, perceptual realism, and the quality of the aesthetics between CNN, GAN, diffusion and transformer based models. Diffusion and transformer evaluators have significantly better scores and that means better performance in capturing complex aesthetic characteristics and better matching machine learning results with human visual perception.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Model-Wise Comparative Trends in Aesthetic Quality Metrics

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Technical and Computational Constraints

Technical and computational limitations are one of the major issues with implementing machine learning to digital aesthetics. State-of-the-art generative models, like diffusion models and sizeable transformers, require significant computation, in the form of high-performance GPUs, large memory requirements, as well as long training times. These requirements restrict the independence of independent artists, small institutions, and resource limited settings. Moreover, the model training and inference are also energy-consuming and this is a cause of concern as far as sustainability and environmental implication is concerned. Aesthetic generation in real-time and interactive creative applications can only worsen these limitations because they demand processing in low-latency without degrading visual quality. Scalability and efficiency are therefore viewed as a major constraint that should be overcome by optimizing the model, lightweight systems and energy conscious AI.

5.2. Data Bias and representation problems

A major constraint of the aesthetic system of machine learning is dataset bias. The vast majority of large-scale visual collections are based on the prevailing cultural, geographical, and aesthetic standards, which tend to be underrepresentative of indigenous, local, and non-mainstream art. Subsequently, trained model can generate biased aesthetic preference and disenfranchise the different visual languages. The problems of representation also include the imbalanced annotations, the inconsistency of the subjective rating, and the loss of the contextual information during the data curation. These prejudices do not only have impacts on generative diversity, but they also impact evaluative judgments, causing biased aesthetic judgments. To counter the problem of dataset bias, it is essential to collect data inclusively, document it transparently and engage various artistic communities in the curation process.

5.3. Limitations of Current Aesthetic Evaluation Metrics

The existing aesthetic evaluation measures are not imbued with the capacity to entirely describe the aesthetic experience of the human beings. Quantitative measures like FID, SSIM and LPIPS are more concerned with perceptual similarity and visual quality, frequently overlooking the meaning, culture and emotion. Though predictive accuracy measures provide standard comparative data, it does not capture subjectivity as well as changing aesthetic ideals. Human assessment though is richer but it brings about variability and scalability issues. This detachment points to the necessity of hybrid assessment systems, combining computational measures with contextual, interpretive, and human-centered approaches to assessment, as a way of getting a more comprehensive aesthetic judgment.

6. Conclusion

This paper has shown that machine learning has emerged as one of the most significant influences in the process of forming the modern aesthetic of the digital world, which is fundamentally changing the way visual representations are produced, judged and perceived. The results of the systematic experimentation based upon a single aesthetic dataset and various paradigms of models reveal a visible development of progression in terms of feature-driven convolutional networks to context-aware transformers and high-fidelity diffusion models. Although certain research findings vary in applicability, quantitative outcomes generally prove that diffusion-based methods lead in predictive accuracy, perceptual realism, stylistic consistency, and human expert assessment to accept their greater ability to simulate intricate aesthetic forms. Transformer based assessors also enhance aesthetic judgement by harmonising the algorithmic and human judgement based on the global compositional reasoning. The outcomes of performance, in addition to gains, bring out important qualitative information. Even though machine learning broadens the range of aesthetic diversity and increases the speed of creative exploration, it also threatens to lead to convergence of styles and cultural bias as well as making less transparency. The human expert judgment indicates that aesthetical value is not constrained by numeric values and should focus more on emotional expressiveness, originality and contextual significance. Such results highlight the importance of the inclusion of human-centric assessment, interpretability features and multiculturalized datasets in the aesthetic AI systems. What is important is the fact that the study demonstrates that machine learning does not substitute artistic agency, but transforms it into a co-creation model between humans and AI. Responsible adoption of machine learning is creatively transformative, educative, and preservatory to artists, designers and cultural institutions. In the end, to progress and develop the digital aesthetic in the era of machine learning, it is necessary to reconcile technical ingenuity and ethical considerations, the culture and human values in order to have the sustainable and meaningful creative futures.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Barrios-Rubio, A. (2023). The Informative Treatment of COVID-19 in the Colombian Radio: A Convergence of Languages and Narratives on the Digital Sonosphere. Comunicación y Sociedad, 20, e8446. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2023.8446

Burquier, M.-P. (2025). Vertigo in the Age of Machine Imagination. Arts, 14(6), Article 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060145

Cheng, M. (2022). The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. Proceedings, 81(1), Article 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022081110

Cone, L., Brøgger, K., Berghmans, M., Decuypere, M., Förschler, A., Grimaldi, E., Hartong, S., Hillman, T., Ideland, M., and Landri, P. (2021). Pandemic Acceleration: COVID-19 and the Emergency Digitalization of European Education. European Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211041793

Guo, D. H., Chen, H. X., Wu, R. L., and Wang, Y. G. (2023). AIGC Challenges and Opportunities Related to Public Safety: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 4(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.08.001

Leong, W. Y. (2025). Machine Learning in Evolving Art Styles: A Study of Algorithmic Creativity. Engineering Proceedings, 92(1), Article 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025092045

Maghsudi, S., Lan, A., Xu, J., and van der Schaar, M. (2021). Personalized Education in the Artificial Intelligence Era: What to Expect Next. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 38(3), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2021.3055032

Mun, S. J., and Choi, W. H. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Neoplasticism: Aesthetic Evaluation and Creative Potential. Computers, 14(4), Article 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14040130

Munir, H., Vogel, B., and Jacobsson, A. (2022). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches in Digital Education: A Systematic Revision. Information, 13(4), Article 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13040203

Oksanen, A., Cvetkovic, A., Akin, N., Latikka, R., Bergdahl, J., Chen, Y., and Savela, N. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Fine Arts: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1, Article 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2023.100004

Orton-Johnson, K. (2024). Digital Culture and Society. Sage Publications.

Pedrero-Esteban, L. M., and Barrios-Rubio, A. (2024). Digital Communication in the Age of Immediacy. Digital, 4(2), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital4020015

Pérez-Escoda, A., Pedrero-Esteban, L. M., Rubio-Romero, J., and Jiménez-Narros, C. (2021). Fake News Reaching Young People on Social Networks: Distrust Challenging Media Literacy. Publications, 9(2), Article 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications9020024

Piñeiro-Otero, P., and Pedrero-Esteban, L. M. (2022). Audio Communication in the Face of the Renaissance of Digital Audio. Profesional de la Información, 31(5), e310507. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.sep.07

Tomasevic, N., Gvozdenovic, N., and Vranes, S. (2020). An Overview and Comparison of Supervised Data Mining Techniques for Student Exam Performance Prediction. Computers and Education, 143, Article 103676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103676

Vlachou, S., and Panagopoulos, M. (2023). Aesthetic Experience and Popularity Ratings for Controversial and Non-Controversial Artworks Using Machine Learning Ranking. Applied Sciences, 13(19), Article 10721. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131910721

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.