ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Augmented Reality in Photographic Storytelling

Harsh Tomer 1![]()

![]() ,

Nidhi Tewatia 2

,

Nidhi Tewatia 2![]() , Simranjeet Nanda 3

, Simranjeet Nanda 3![]()

![]() ,

Abhinav Srivastav 4

,

Abhinav Srivastav 4![]()

![]() ,

Avinash Somatkar 5

,

Avinash Somatkar 5![]() ,

,

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Vivekananda Global

University, Jaipur, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

3 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

4 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fashion Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

5 Department

of Mechanical Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune,

Maharashtra, 411037, India

6 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of

Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

AR has

transformed the visual and experiential aspect of the photography story

telling by uniting the definitions of both in one place, blending the static

visuals with the interactive spatial based stories. AR turns the viewer into

an active participant instead of the passive one, because of its capacity to

extend photography into a multisensory, three-dimensional space, and is

creating new avenues of meaning, feeling, and interaction. Embodied

interaction, spatial computing, and visual composition merge to create

AR-based photography as an art form of hybridity where action, perception,

and interest come together to create the narrative. This amalgamation does

not only add deeper aesthetic qualities but also the communicative power of

photography by reaching out to the physical and virtual. Photography has long

been a medium of remembrance and representation; AR is currently bringing it

back to the reality as a medium of participation and presence. The paper

follows this development in museum installations, interventions in the urban

storytelling, and personal memory project demonstrates how spatial narratives

will make art more democratic and create empathy and cultural continuity. The

presented structure and analysis findings emphasize the role of AR in engagement,

emotional appeal, and interpretive cognition that is backed by both

quantitative analytic data and qualitative audience feedback. Although the

technical calibration, data ethics, and cultural authenticity have been

problematic, the emergent technologies based on AI adaptivity, WebAR

platforms, and blockchain provenance have the potential to further streamline

the field. Finally, AR photographic storytelling is a meeting of artistic

vision and digital intelligence which makes photography living and responsive

as a form of narration that builds a bridge between image, space, and human

experience. |

|||

|

Received 12 June 2025 Accepted 26 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Harsh

Tomer, harsh.tomer@vgu.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6886 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Augmented

Reality, Photographic Storytelling, Spatial Interaction, Visual Culture,

Digital Art, Interactive Photography, Audience Perception, AI-Driven Media |

|||

1. The Evolving Language of Photographic Storytelling

Photography has always been a memory,

an emotion and a story a visual medium in which the reality is remembered and

recreated. However, with the ever-increasing use of technology which is

obliterating the physical and digital divide, photographic storytelling has

entered a phase of reinvention Ryan (2015). The introduction of Augmented Reality (AR) has enhanced

the conventional photographic frame into a full-sensory and inclusive space

where pictures are no longer considered as fixed depictions but as moving and

spatially conscious ones. This change is not merely a change in technology, but

a radical re-corporation of the work of authorship, viewership, semiotics of

the photographic image itself. In the most basic terms, augmented reality is

the superposition of digital content in the form of animation, sound, text or

3D objects on actual images, generating a collage between the real and the

virtual Lee et al. (2015). In its application to photography, this blending makes

possible the narrative possibilities of images to be developed in three

dimensions. Having a smartphone or an AR headset in hand, the viewer is

transformed into an active user, experiencing the strata of visual and audio

sense as opposed to passively watching a framed scene Figueiras (2016). In this respect, AR reshapes the act of photography as

documentation in space as a story, where point of view, motion, and interaction

are used to remake the emotional and thinking process of the viewer towards the

picture.

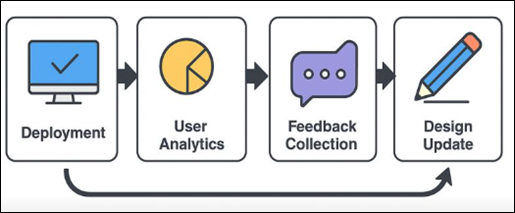

Figure 1

Figure 1

Circular Framework Depicting How Digital

Layers

The new mode of narration is in dispute

with the ontology of the photograph. The photo has conventionally been seen as

an indexical trace a mark of an actual event or moment. In AR-based narratives,

though, the image goes beyond its evidence purpose and becomes a living

interface Galatis et al. (2016). AR photography is a way of bringing fluidity to the visual

storytelling through interactive triggers, temporal sequencing, and user-driven

exploration which allows new interpretations to change with each engagement.

The story is no longer determined by the frame of the photographer but it is

constantly rewritten by the audience. In terms of culture, the fusion of AR and

photography also rearranges the representation of memory, identity, and place Chatzopoulos et al. (2017). The augmented photographic spaces enable anchoring the

personal stories into the physical space which transforms the public spaces

into the living archives and personal photographs into the shared and immersive

experiences. The distinction between the storyteller and the audience is

blurred and the narrative ecology produced is co-creative.

2. Historical and Theoretical Foundations

The history of photographic narrative

is closely connected with the historical path of visual rhetoric and mediation

by technology. Whereas the analog darkroom culture of the 19th and 20th

centuries presented a series of darkroom practices that defined the mode of

photography, its capture, construction, and meaning, the current state of the

art of augmented reality (AR) overlays has redefined the mode of photography,

its capture and meaning construction in addition to its construction. The

materiality of the photograph film grain, and the feeling of the prints were

inherent in the analog era and were part of the authenticity. This materiality

led to the feeling of permanence and indexical truth, which anchored images as

a witness of time and space which was reliable Panou et al. (2018). The emergence of digital imaging in the 1990s has brought

photography to the era of dematerialization. Silver halides were substituted by

pixels, printing was substituted by the screens, and this enabled manipulation,

and immediate distribution. The photograph ceased to be an object of stone; it

became a moving digital fluid, which can be reproduced, edited indefinitely.

This shift erased the distinction between documentation and the act of

creation, introducing some new aesthetic paradigms where the image authenticity

was a bargain between perception and computations Dd Goh et al. (2019). To follow this change in a systematic way, Table 1 illuminates the developmental phases of photographic

narration, matching the most important technological changes with their

artistic and narrative impacts. The whole process of augmented reality

integration is the culmination of these historical changes Liestøl (2019). Based on phenomenological, semiotics, and space narrative

theories, AR erases the two-dimensional border of a photograph and places it in

real-life explorable spaces. These theories were used to get a base on how AR

is able to replace a visual story telling that is just followed by observation

into a form of participation. Table 1 below puts these frameworks into context and how they

directly relate to AR photography.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Theoretical Frameworks Influencing AR Photographic Storytelling |

|||

|

Theoretical Lens |

Key Proponents |

Core Concept |

Relevance to AR Photography |

|

Phenomenology Aliprantis and

Caridakis (2019) |

Merleau-Ponty, Husserl |

Embodied perception and lived experience |

AR engages bodily movement and spatial awareness |

|

Semiotics Tejedor-Calvo

et al. (2020) |

Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco |

Signs and meaning in image interpretation |

AR layers create polysemic narrative contexts |

|

Postmodernism Russo (2021) |

Baudrillard, Lyotard |

Fragmented, participatory narratives |

AR dissolves fixed authorship and authenticity |

|

Spatial Narrative Theory Tong et al.

(2018) |

Ryan, Jenkins |

Story unfolding through space and interaction |

AR storytelling integrates location and movement

into narrative flow |

All these theoretical approaches

explain the reason why AR storytelling cannot be limited to the sole effect of

visual enhancement it is a paradigm shift in the phenomenology of viewing. The

picture turns out to be a spatial and interactive interface as opposed to a

picture. Movement, gesture, and perception allow viewers to become participants

to recreate the story in real-time. Hence, the photographic storytelling by AR,

is not the break in the tradition but the logical continuation of the

historical development of photography in terms of the move of the application

of photography as a means of representation towards the experience of being in

the image and as the seeing towards the being in the image.

3. Proposed Design Framework for AR-Based Photographic Storytelling

Photographic storytelling using

Augmented Reality (AR) is conceptually based on a collision of the visual

semiotics, spatial computing, and interactive narrative design. In contrast to

traditional photography, in which the narrative meaning is limited by a fixed

frame, AR photography exists in a broader field of space where the viewer will

become a perceiver and an actor. The structure focuses on merging visual

levels, sensory experience, and participation by the end-user by making

photographs a dynamic experiential environment, instead of a fixed composition.

On the structural level, the AR storytelling process starts with the

visual-spatial composition of the picture that determines the contextual

anchors of augmentation.

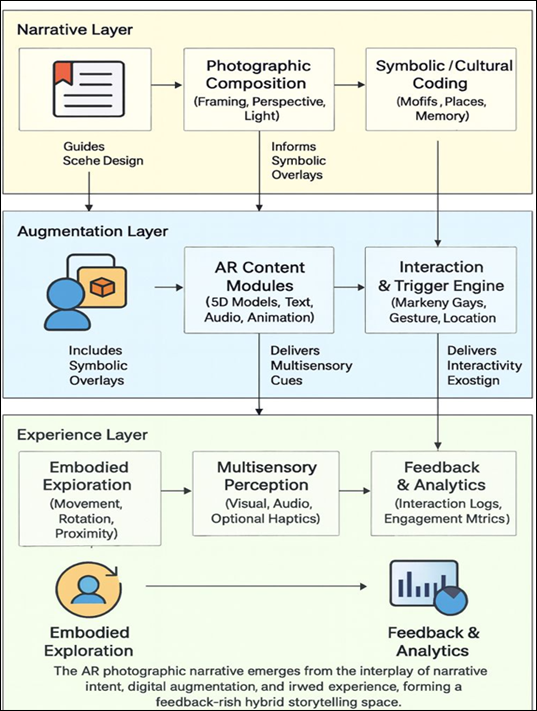

Figure 2

Figure 2

Workflow for AR Photographic Storytelling

Creation

Each photo is used as a canvas to

digital layertap of 3D objects, animation, ambient sound, or context texts that

improve the continuity of the story. These virtual components can be oriented

to physical coordinates through the recognition of objects and mapping the

scene to make the augmented layer reactive in respect to the viewer and their

movement. It is a form of a moving and living dialogue between the real and the

virtual produced through this spatial correspondence enabling the storytelling

to proceed in movement and perception. An important part of the framework is

multimodal fusion which combines visual, auditory and occasionally haptic

feedback to produce emotional and cognitive involvement Esser and Vliegenthart (2017). This practice is built on the theory of embodied

interaction, meaning of which is created with the help of sensual plunge and

bodily discovery. The gestures, gaze or voice input of the viewer becomes a

condition and the layers to the story are brought out or altered creating a

feedback-driven loop between the audience and the artwork. This interactivity

turns spectatorship into co-authorship, which is the viewer as a partner who is

active in determining the narrative results:

1) Narrative Layer: outlines the thematic content and

plotting that is incorporated in the photograph.

2) Augmentation Layer: realizes the visual and auditory

aspect in relation to the physical setting.

3) Experience Layer: reflects the interpretation,

movement, and emotional feeling of the user, which is returned into the logic

of adaptive stories implemented in the system.

Al the layers

depicted in diagram 2, are a continuum of physical image, digital augmentation,

and human perception becoming unified. This paradigm places AR not only as a

photographic additional feature, but as an aesthetic development of the space

of the narrative, as a part of visual art, technology, and phenomenological

experience.

4. Existing Design AR Design Technology

The scientific foundation of AR-based

photographic narrative is established based on a system of structures mainly

ARKit, ARCore, WebAR, and Unity-based toolchains, which allow spatial tracking,

surface recognition, and real-time production of graphic overlays. Practically,

the platform decision does not come down to pure technicality, but the platform

influences the manner in which a narrative can be performed, how it is made

available to the audience, and the degree to which the system can be made responsive

on the ground. ARKit and ARCore, as an example, provide powerful sensor fusion

and plane detection closely coupled with both iOS and Android systems, thus

being suitable in location-based photographic storytelling that is based on

consistent tracking and high-quality rendering. WebAR, in its turn, focuses

more on accessibility via the browser, and the lack of graphical richness in

favor of frictionless entrance, which is imperative in the case of intervention

in the public art and in the conditions of exhibitions, where some audience may

be unwilling to install the app. Unity is an orchestration platform, which

enables the artist researcher to create once and run in any of several AR

runtimes with custom shaders, particle systems, and interaction scripts

designed to fit photographic aesthetics.

Table 2

|

Table 2 AR Platforms for Photographic Storytelling |

||||

|

Platform / Stack |

Device Ecosystem |

Strengths for Photographic Storytelling |

Limitations |

Typical Use Case |

|

ARKit Wang and Zhu

(2022) |

iOS (iPhone, iPad) |

High-quality tracking, light estimation, smooth

integration with native camera and gallery |

Restricted to Apple devices |

Gallery-based AR photo essays, curated museum

experiences |

|

ARCore Boboc et al.

(2022) |

Android devices |

Broad device reach, robust plane detection,

integration with Google services |

Fragmented hardware quality, variable performance |

Urban AR street-photography narratives,

site-specific works |

|

WebAR (e.g., 8th Wall, WebXR) Gong et al.

(2022) |

Cross-platform browsers |

No app install, easy access via URL/QR, ideal for

public engagement |

Limited graphics performance, constrained access to

sensors |

Outdoor AR photo walks, quick exhibition

augmentations |

|

Unity + AR Foundation Daineko et al.

(2022) |

Multi-platform (iOS, Android, some XR headsets) |

Single project, multiple builds; advanced visual

effects, complex interaction logic |

Higher learning curve, longer build cycles |

Complex, multi-scene AR photo installations with

interactive story branching |

AR photographic storytelling design

methodology can thus be envisioned as being an iterative pipeline where

conceptual and photographic choices are made at the start of the design and the

end is interactive deployment and evaluation. It begins with the planning of

stories and images where narrative lines, visual patterns and space contexts

are established. These choices lead to directed image capture such as

consideration of parallax, depth indication and negative space that will

subsequently accommodate digital additions. During the stage of producing the

assets, 3D, textual overlays, soundscape, and subtle animations are produced or

obtained, with the stylistic unity of these elements with its underlying

photographs Daineko et al. (2023). The interaction design forms the second layer of the

approach that is critical. In this case, gesture, gaze and proximity stimuli

are stipulated to disclose narrative levels in a progressively graded manner

inviting to exploratory behaviour as opposed to one-time viewing. Prototyping

is based on on-device testing at a fast pace to create a refined interaction

threshold, realignment of the overlay and performance optimization according to

device and lighting conditions Hu et al. (2023).

5. Proposed Design Methodology for AR Photographic Storytelling Creation

The suggested design process offers a

well-organized, stage-by-stage platform, which incorporates artistic

creativity, spatial computing, and user experience design into a unity of AR

storytelling medium. It is structured around six consecutive, but repetitive

steps, which make sure that the narrative vision, as well as technological

implementation, develops simultaneously.

Step 1: Conceptualization and Figuring out of the story

This process starts with establishing

the thematic intent as well as the narrative structure of the photographic

narrative. At this point, the producer determines the emotional emphasis,

message and the required audience engagement. To visualize the way the story is

going to progress in augmented space, storyboards, and narrative flow diagrams

are created.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Process of Conceptualizing Narrative Structure and Planning Interactivity in AR Photographic Storytelling

The photos are given a narrative role

of either an entry point, transition, or an immersive anchor. Interactive

stimuli like gestures, gaze or distance are conceptually designed to determine

how the users would interact with the augmented layers. Such tools as Figma and

visual scripting block can help to move conceptual ideas into early prototypes.

At this stage, it is already known that the story is worth having aesthetic

value and interactive logic but not yet ready to be implemented technically.

Step 2: Photographic Data Capture and Contextual Data

Capture

Once conceptual planning has been done,

the next step is to capture the content of the photographic material and the

environmental metadata on which the AR experience will be based. DSLR or smart

phone cameras with depth sensors or LiDAR scanners are used to take the

high-resolution images which are needed to provide proper spatial referencing.

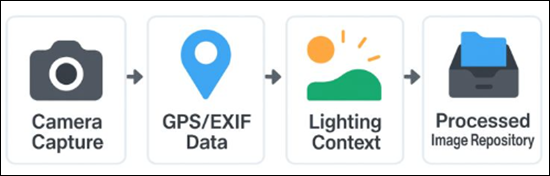

Figure 4

Figure 4

Workflow of

Photographic Capture Integrated with Contextual Metadata Acquisition for

Spatial Anchoring.

Coupled with the photographs, there are

a set of contextual information like GPS positions, brightness of the ambient

light, and metadata with regard to orientation. This context information is

used later to make accurate spatial registration of digital overlays. Tone,

contrast, and detail activation in the images are done using editing software

such as Adobe Photoshop or light rooms. The result of this process is a refined

visual dataset that could be augmented and also include environmental metadata

to be integrated with AR.

Step 3: AR Asset Development and

Integration

After the foundation photo material is

ready, the design stage progresses to the creation of digital additions to the

photos that now broaden the narrative abilities of the photographs. Here, the

visual narrative is supplemented with 3D models, as shown in Figure 5, animation, soundscapes as well as text layers. These

assets have been designed in accordance with the concept of narrative coherence

in which all digital pieces reinforce the original photograph and not distract

the viewer.

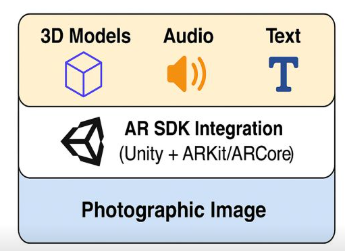

Figure 5

Figure 5 Integration of Digital Assets and

Interactive Overlays onto Photographic Layers for AR Storytelling

Artists create light and optimized

assets that can be rendered on mobile with the use of Blender, Maya, or

Cinema4D. These resources are then brought into Unity and connected up with

SDKs such as ARKit (iOS) or ARCore (Android), and comprise the augmented layer

that will dynamically engage with the real world photographic space. This is

where the intent of narrative is turned into spatial interactive experiences.

Those photographic and digital resources are put together in a 3D AR

representation in Unity whereby spatial orientation is realized via the SLAM

(Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) methods. The anchor in the real world

coordinates is performed by surface detection and plane tracking which puts the

anchor at the correct position in the real world.

Figure 6

Figure 6

Scene Assembly

Process Showing Slam-Based Spatial Mapping and Real–Virtual Content Alignment

The camera angles, lighting, and motion

restrictions are predetermined by designers so that the illusion of being

immersed into the world is always constant. The interaction points of the

scene, including tap areas, motion triggers, audio hotspots, are included in

the scene, as illustrated in figure 6 the outcome of this step is the creation

of a functional AR environment, which physically and visually interacts with

the surrounding environment of the user and converts the still images into

spatial stories.

Step 5: User Interaction Design and

Testing

After assembling the scenes, the second

phase is to test and development of user interaction systems to create a system

of interaction that is intuitive and emotionally sensitive. Initial prototypes

are tested on various devices to test the tracking performance, responsiveness

and also usability. The participants will be monitored when engaging with the

AR material in order to determine the instances of disorientation, stimulation,

or aesthetic pleasure.

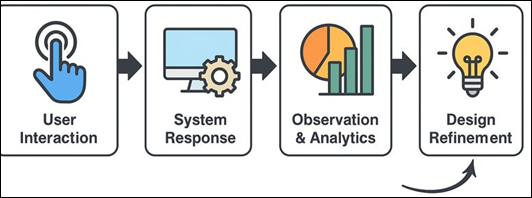

Figure 7

Figure 7

Iterative Loop

Representing User Testing, Data Collection, and Refinement of AR Interactions.

Quantitative data, dwell time and

trigger frequency is recorded and qualitative interviews are recorded in the

form of emotional responses and cognitive impressions. The feedback is applied,

which is symbolized by the number 7, to make the interaction design more

accurate, asset performance more productive, and the narration sequence more

understandable. This would be taken so that experience is immersive,

comfortable, and narratively consistent with diverse users and situations.

Step 6: Deployment, Evaluation, and

Iterative Refinement

The last process is the publication,

surveillance, and enhanced AR photographic experience. The final project will

be released on the platform of App Store, Google Play, or WebAR to access the

project via a browser. Embedded analytics makes a record of engagement

measures, interaction trends, and retention.

Figure 8

Figure 8 Continuous Evaluation and

Iterative Enhancement Cycle for Sustaining AR Photographic Storytelling

Experiences.

Surveys and observations done after

deployment provide information on the level of user satisfaction, interpretive

comprehension, and emotional richness. According to these findings, both the

artistic and technical side of the experience are optimized by the design team.

The updates can be done iteratively and can be in terms of better spatial

accuracy, better visual effects, or adaptive features that are driven by AI.

This is a cyclical process, which guarantees constant improvement of the story

telling structure and sustainability of the project in the long term as

demonstrated in Figure 8.

And last, the deployment and assessment

loop is closed, analytical modules know dwell time, hotspots interactions, and

navigation patterns and qualitative feedback is made to know the emotional

resonance and interpretive richness. The lessons of this stage are used to make

changes to the technology set up and narrative form, cementing a

research-through-design practice, in which artistic exploration and

methodological strictness are developed alongside each other. This cyclical

process is shown in Figure 4, which perceives the process of creating an AR

photographic storytelling through concept, design, implementation, and feedback

in a cyclical way.

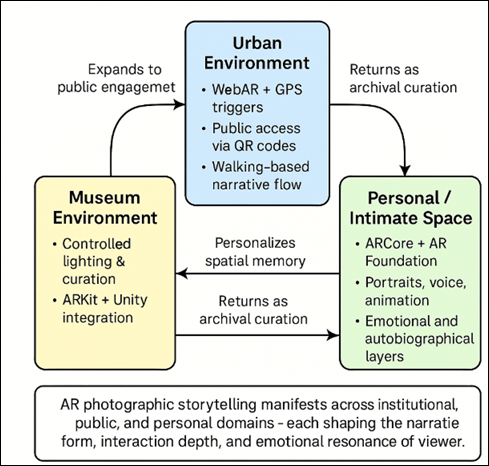

6. Case Studies in Augmented Photographic Narratives

The real-life examples of the Augmented

Reality (AR) use in photographic storytelling show that this hybrid medium can

be used to go beyond traditional showing of images and can provide immersive,

participatory experiences. AR photography has been developed over the years

through a variety of contexts in the form of museum exhibitions, urban

interventions, in addition to personal archives as an expressive language of

spatial storytelling that marries artistic vision with computational

intelligence. In this section, we consider the exemplary case studies, which

exemplify the creative, technical, and experiential aspects of AR-based works

in photography.

Case Study-A] AR Photography

Exhibitions in Museums.

Museums are now serving as fertile

grounds to experiment with AR photography, a controlled and yet fascinating

setting where people are able to navigate through historical photographs and

digital overlay in the present day. As an example, an AR-enabled installation

could have archival images of a heritage facility alongside 3D recreations or

oral histories, which could be played as people wander through the

installation. Through the fusion of ARKit or Unity systems, curators will have

the ability to place holographic layers in space, restoring missing parts of an

architecture or showing time-lapse change of the place.

This and the visual understanding is

not just enhanced, but also creates mental empathy in the viewers who do not

simply watch the past, they enter its recreated atmosphere. Such installations

usually provide their audience analytics that reveal a statistically

significant increase in dwell time and emotional resonance scores, indicating

that AR improves the level of learning retention and aesthetic immersion.

Storytelling in the city and AR Street photography

City AR storytelling makes cities

living photographic galleries. Images on walls or computer screens are

transformed into geo-tagged narrative doors, which can be accessed by

smartphones by means of WebAR links or QR triggers. The city in itself stages out,

and in every photograph, a subtextual narrative is played out in the context of

place, time, and movement. As an example, an AR street photography experience

could enable people walking by to point their phones at an image of a long-gone

market and see an overlay in 3D, recreating the historical feel of it, with

background noises and soundbites of past traders. This site-specific narrative

design recaptures the memory of a city, bringing back photography to the

collective heritage as opposed to a lone record. The combination of

GPS-triggered overlays and photogrammetric assets suggest a more and more

narrative experience of walking, which equates to narrative advancement.

Case Study-B] Personal Memory

Narratives with the help of AR Portraiture

When it comes to personal narration, AR

portraiture can enable the viewer to save and reprocessing the memory in the

form of the interactive photographic layers. Personal photographs may be

enhanced with short video clips, voice records, or loops of animation to

recreate the emotional background with the help of such tools as ARCore and the

AR Foundation of Unity. We can use the example of a portrait that can show a

lively entry of the diary or a small secret message when a viewer comes to it.

These projects carry the ideas of the photograph as the mnemonic object to the

actual experience that combines the sense of the emotional memory and the

spatial interactivity. This form of AR storytelling is consistent with

post-phenomenological theories, in which digital media determines the

definition of human experience of memory, intimacy, and self-representation. In

order to bring together the lessons of these cases,

Table 3

|

Table 3 Summarizes the Comparative Features, Technologies, and Impacts Across these Case Studies Disussed Above |

||||

|

Case Study Context |

AR Platform / Tools |

Narrative Strategy |

Audience Interaction |

Key Impact |

|

Museum Exhibition |

ARKit + Unity |

Temporal layering, reconstruction of historical

imagery |

Spatial navigation through gallery |

Enhanced cultural immersion and interpretive

learning |

|

Urban Street Photography |

WebAR + GPS |

Geo-tagged storytelling and site-specific memory

reconstruction |

Walking-based discovery and location-triggered

activation |

Recontextualization of public space and collective

heritage |

|

Personal Memory Portraits |

ARCore + AR Foundation |

Emotional narrative layering with voice and

animation |

Gesture-based and proximity-triggered exploration |

Deepened affective connection and self-reflexive

storytelling |

The comparison shows that all three

contexts are based on embodied interaction, multisensory immersion, and

co-creative narrative design in spite of the fact that the technological

architectures vary. The institutional to personal variety of AR environments

depict the way in which photography may transform into a multidimensional

artifact to become a multidimensional ecosystem of storytelling that engages

viewers both emotionally and spatially.

7. Artistic and Cultural Implications

The fact that Augmented Reality (AR) is

integrated into the process of telling stories in photography promises to

introduce a radically new shift in the artistic and cultural paradigm of visual

expression. Combining the documentary accuracy of photography with the spatial

interactivity of AR, a new language is formed a language that questions the

concepts of authorship, time, and material space of the image. This part will

look into the artistic implications, cultural transformations as well as

ethical implication presented by this amalgamation of art and technology. AR

photographic storytelling at the artistic level reconstructs the process of

seeing. The customary photography seals a scene in a lifeless composition by

fixating the eye of the viewer on one point of view. AR destroys that fixity

and makes the viewer enter the frame to navigate in the narrative space. The

artwork is transformed into an interactive system which reacts to gesture,

closeness, and interest and it changes with each encounter. Such a spatial

immersion reestablishes a sense of agency towards the audience making

spectators co-producers of meaning. The artist thus moves out of being an

individual author, into being a narrative architect, coordinating temporal and

sensual experiences, which emerge during embodied movement of the viewer.

Figure 9

Figure 9 Audience Experience Comparison between Traditional and AR

Storytelling

In order to systematize the capture of

these transitions, Figure 9 describes the artistic changes that happen when photography

shifts to an AR-based mode of narrative. The aesthetic ontology of the

photograph is also changed as a result of the transformation. The image in

AR-based works is not just the depiction of the reality but a time interface in

which the digital and physical layers exist at the same time. This way, the

photograph is no longer tied down by its fixed position of a visual record but

rather it becomes a performative space a stage of storytelling that is changed

by being engaged in. It is similar to the postmodern idea of the open artwork

of Umberto Eco, where the interpretation and participation are finished parts

of the artistic process. In these regards, AR photography is more than

depiction, but authorship experienced, as time, space and affect are all merged

in one creative process. AR photographic storytelling removes the lines between

memory, heritage, and lived experience culturally. It brings archives back to

life in the museums where historical photographs can communicate with the real

space. It serialises the narrative in urban spaces by incorporating the local

stories into the common surroundings. At a more personal level, it converts

personal snapshots into the interactive memory capes.

8. Conclusion

The study of Augmented Reality (AR) in

photographic storytelling brings forth a paradigm change in the way the

narrative is being conceived, experienced, and remembered. Combining the

elements of photographic realism and interactive space arrangement, the AR

turns the picture into an interface of a living story, re-constructing the

borders between the viewer, the creator, and the surrounding world. The

photograph that used to serve as a static time-note turns into a multisensory

field which can change in accordance to the presence and engagement of the

viewer. Artistically, the AR storytelling places the photographer in the role

of a building designer, mixing aesthetics, movement, and visually engaging

experiences into unified experiences. With this reconfiguring, the passive

viewing act is disbanded and co-creation is established in which the audience

directs, interprets and has an emotional contribution in the narrative being

played out. Not only does such participatory storytelling renew photographic art

but it also makes it consistent with current theories of embodied perception

and experiential authorship. The implications are culturally far reaching. AR

photography makes art more accessible through entrenching visual stories in

museums, on the streets, and in personal space and transforms ordinary spaces

into platforms of memory and imagination. The medium forms the gap between

historical archives and the present culture, inviting people to recollect

together and engage in intercultural communication. However, such authority is

accompanied by a sense of responsibility that maintains ethical integrity,

transparency of data and cultural authenticity in the process of augmenting and

communicating stories. Various technological and design issues continue to exist

including variability with devices and privacy issues but more recently

emerging technologies like AI adaptivity, accessing WebAR, and blockchain

provenance are progressively conquering these obstacles.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aliprantis, J., and Caridakis, G. (2019). A Survey of Augmented Reality Applications in Cultural Heritage. International Journal of Computer Methods in Heritage Science, 3, 118–147.

Boboc, R. G., Băutu, E., Gîrbacia, F., Popovici, N., and Popovici, D. M. (2022). Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Applied Sciences, 12, 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199859

Chatzopoulos, D., Bermejo, C., Huang, Z., and Hui, P. (2017). Mobile Augmented Reality Survey: From Where We Are to Where We Go. IEEE Access, 5, 6917–6950. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2695032

Daineko, Y., Alipova, B., Ipalakova, M., Bolatov, Z., and Tsoy, D. (2023). Angioplasty Surgery Simulator Development: Kazakhstani Experience. In Extended Reality. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 14219, 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42142-6_42

Daineko, Y., Tsoy, D., Seitnur, A., and Ipalakova, M. (2022). Development of a Mobile E-Learning Platform on Physics Using Augmented Reality Technology. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (IJIM), 16, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v16i03.31317

Dd Goh, E. S., Sunar, M. S., and Ismail, A. W. (2019). 3D Object Manipulation Techniques in Handheld Mobile Augmented Reality Interface: A Review. IEEE Access, 7, 40581–40601. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2908593

Esser, F., and Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Comparative Research Methods. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1–22. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0011

Figueiras, A. R. d. P. (2016). How to Tell Stories Using Visualization: Strategies Towards Narrative Visualization (Ph.D. dissertation). Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. https://run.unl.pt/handle/10362/20778

Galatis, P., Gavalas, D., Kasapakis, V., Pantziou, G. E., and Zaroliagis, C. D. (2016). Mobile Augmented Reality Guides in Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 8th EAI International Conference on Mobile Computing, Applications, and Services (MobiCASE’16), 11–19, Cambridge, U.K. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.30-11-2016.2260035

Gong, Z., Wang, R., and Xia, G. (2022). Augmented Reality (AR) as a Tool for Engaging Museum Experience: A Case Study on Chinese Art Pieces. Digital, 2, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.3390/digital2020003

Hu, W., Han, H., Wang, G., Peng, T., and Yang, Z. (2023). Interactive Design and Implementation of a Digital Museum Under the Background of AR and Blockchain Technology. Applied Sciences, 13, 4714. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13114714

Lee, B., Riche, N. H., Isenberg, P., and Carpendale, S. (2015). More Than Telling a Story: Transforming Data Into Visually Shared Stories. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 35, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCG.2015.18

Liestøl, G. (2019). Augmented Reality Storytelling Narrative Design and Reconstruction of a Historical Event in Situ. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (IJIM), 13, 196. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v13i12.10743

Panou, C., Ragia, L., Dimelli, D., and Mania, K. (2018). An Architecture for Mobile Outdoors Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 7, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi7120463

Russo, M. (2021). AR in the Architecture Domain: State of the Art. Applied Sciences, 11, 6800. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11206800

Ryan, M.-L. (2015). Emotional and Strategic Conceptions of Space in Digital Narratives. In H. Koenitz, G. Ferri, M. Haahr, D. Sezen, and T. İ. Sezen (Eds.), Interactive Digital Narrative History, Theory and Practice, 106–120. New York, NY, USA; London, U.K.: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315683328

Tejedor-Calvo, S., Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., Moncada-Moncada, A.-J., and Alencar-Dornelles, M. (2020). Journalism That Tells the Future: Possibilities and Journalistic Scenarios for Augmented Reality. Profesional de la Información, 29, 6. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.06

Tong, C., Roberts, R., Borgo, R., Walton, S., Laramee, R., Wegba, K., Lu, A., Wang, Y., Qu, H., and Luo, Q. (2018). Storytelling and Visualization: An Extended Survey. Information, 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/info9030065

Wang, C., and Zhu, Y. (2022). A Survey of Museum Applied Research Based on Mobile Augmented Reality. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 2926241. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2926241

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.