ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Digital Printmaking through AI Style Transfer

Pathik Kumar Bhatt 1![]()

![]() ,

Narayan Patra 2

,

Narayan Patra 2![]()

![]() ,

Muthukumaran Malarvel 3

,

Muthukumaran Malarvel 3![]()

![]() ,

Eeshita Goyal 4

,

Eeshita Goyal 4![]() , Shriya Mahajan 5

, Shriya Mahajan 5![]()

![]() ,

,

Abhijeet Deshpande 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Geography, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, Siksha

'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University),

Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

3 Department

of Computer Science and Engineering Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU). Chennai,

Tamil Nadu, India

4 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

5 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

6 Department

of Mechanical Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune,

Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The practice

of digital printmaking is changing due to the combination of computational

accuracy and cultural and artistic expression, which artificial intelligence

is bringing. The neural style transfer and diffusion-based generative models

make it possible to transform the local art culture like Madhubani, Ukiyo-e,

and Cubist abstraction into the digital format and capture their cultural

identity and accepted modern aesthetics. The use of AI in mapping the

stylistic textures, compositional rhythm, and symbolic themes onto new

content areas makes it possible to produce visually and conceptually

stimulating art pieces that do not belong to particular geographic and time

frames. This method is flexible, as demonstrated by three comparative case

studies. The Madhubani-Geometry Fusion exhibits the ability of the algorithm

in maintaining folk symmetry by use of computational patterning; the Ukiyo-e

Metallic Transformation displays the process of neural models to recreate the

sensory effect of depth and reflection of metallic surfaces and ink; and the

Cubist-Textile Hybridization presents the stylistic cross-cultural blending

by using CLIP-guided optimization. Such quantitative measures as the Cultural

Authenticity Score (CAS), Perceptual Realism Index (PRI), and Style Fidelity

prove that algorithmic creativity do not exclude

cultural integrity. In addition to the aesthetic innovation, the study

highlights the ethical and curatorial issues that arise in the AI art. The

integrity in machine-assisted creativity relies on documentation of datasets

in the form of transparency, cultural reciprocity and acknowledgment of the

authorship. The collaboration of placing the artists, algorithm, and cultural

source on the same level of contribution creates a new paradigm of co-authored

creativity in which technology becomes a mediator and not a substitute of the

human imagination. This combination of ethical conscious, cultural

conservation, and computerized art is what constitutes the changing identity

of twenty first century printmaking in digital. |

|||

|

Received 12 June 2025 Accepted 26 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Pathik

Kumar Bhatt, pathikkumar.bhatt35792@paruluniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6885 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI Style

Transfer, Digital Printmaking, Neural Networks, Cultural Heritage, Generative

Art, Authorship, Computational Aesthetics, Curatorial Ethics, Perceptual

Realism |

|||

1. Introduction

Digital

printmaking has become a paradigm practice that guides the haptic culture of analog printing towards the computational creativity of

artificial intelligence (AI). Traditionally based on the methodologies of

etching, lithography, and screen printing, printmaking has been the nexus of

creative exploration and technological development and change. The paradigm

shift in the field occurred with the introduction of the digital technologies,

in particular, deep learning and neural networks Goodfellow et al. (2020). With artificial intelligence,

neural style transfer (NST) and diffusion based

generation have created the possibility of transferring the artistic styles,

textures, and motifs across digital surfaces, essentially pushing the limits of

printmaking beyond its physical limitations. This combination of art and

calculation is not only a change of the tools but the redesigning of the

creative authorship, the aesthetic value and reproduciability

in the art of today. The central concept of AI-driven printmaking is the

principle of style transfer a process where an algorithm removes the stylistic

qualities of a single image (like brushwork, color

palette, or rhythm) and transfers these characteristics to the content of

another one Gatys et al. (2015). Introduced by Gatys et al. as the convolutional neural networks (CNNs),

this procedure makes it possible to break down paintings that combine syntactic

precision with style expressiveness. In digital printmaking, NST enables an

artist to redefine the traditional shapes, rethink folk art, or to create the

illusion of intricate textual surfaces which would be hard to render manually.

In this combination, the digital prints turn out to be hybrid objects that

possess both the computational accuracy and human will to them Isola et al. (2017). The creative agency ceases to

be confined in the hand of the artist alone but in the creative collaboration

of the human intuition and the machine learning systems in an iterative

process.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual

Workflow of Ai Style Transfer in Digital Printmaking

The

aesthetic aspect of AI-based digital printmaking does not remain in copying or

imitating. It provides doors to generative originality, in which machines will

synthesize stylistic elements within a wide range of data, generating visual

representations which mirror an emergent, non-human aesthetic rationale. These

algorithmic metamorphoses permit the re-configuration of visual languages that

bring together, such as the austerity of the geometry of Constructivism and the

inorganic movement of the traditional textile or folk-art patterns. This

recombination of fluids declares the traditional dominance of originality and

reproduction Zhu et al. (2017). In conventional printmaking,

an edition is prized because it can be reproduced and be reproducible, whereas

in AI-based printmaking each iteration has the potential to hold a distinct

stylistic meaning and thus the line between the original and its copies is

unclear. It is also important that these digital artifacts be made to touch.

The current print technologies, including UV-curable inkjet printing,

sublimation, and overprinting 3D textures, enable AI-composed artworks to be

actually manifested on a wide range of surfaces, including canvas and fine art

paper as well as fabric and metallic foils to provide the experience that might

be largely missing in art pieces solely presented on screen. Here, the artist

filters content and styles images and indicates conceptual intent; images are despecified and sanitized; a style transfer core derives

content and style features and combines them under controllable parameters; the

generated outputs are refined through coherence, readability and cultural

authenticity; and ultimately they are sent to print through color

management Hicsonmez et al. (2020), substrate profiling and

edition planning. There is also an accentuation of an archival and feedback

cycle in the figure, with the response of curators and audiences, as well as

new scan and source, into the growth of data sets and the improvement of the

models. The use of AI in printmaking thus brings up deep philosophical, ethical

concerns on the topic of authorship, ownership, and the ontology of the artwork

itself. The aesthetic decision-making process split in the human and the

machine results in the collaboration of the creativity and not in the isolated

activity. The artist is a less monolithic, more of a system designer,

constrainer and curatorial judge, as he or she acts, as captured in the working

system of Figure 1. This is a changing discussion

of a larger cultural shift to the posthuman aesthetics, where art is not

created by the technology but is co-evolving with it Elgammal et al. (2017), Al-Khazraji

et al. (2023). Therefore, AI style transfer

in digital printmaking does not substitute the artist but rather redefines the

very idea of creating printmaking with the new realm of computational poetics

and visual synthesis.

2. Historical and Theoretical Foundations

Figure 2

Figure 2 Traditional vs AI-Driven Printmaking

The

historical development of printmaking is closely connected with the

technological mediation development in art. Since the century of tactile art of

woodcuts, engravings, and and etchings (fifteenth

century), the experimental serigraphs and photo-mechanical prints (twentieth

century), and every technological advancement in the art of printmaking, the

aspect of how artists interact with material, texture and reproducibility has been

altered Tan et al. (2016). In the past, printmaking was a

form of democratizing images and ideas to get them to larger audiences with

maintaining an artisanal authorship. With the digital age, the grid of

production has changed to metal plates and lithographic stones to algorithmic

structures and neural networks. Artificial intelligence, and especially neural

style transfer (NST) and diffusion-based generative modeling,

is a continuation of this tradition and ushers in a new era of algorithmic

printmaking, where art is not only directed by code but also inspired by the

intuition of the artist McCormack et al. (2019). Nevertheless, printmaking

using AI refutes this hypothesis. In contrast to the same mechanical

reproductions, the prints generated by AI, with each being the result of

stochastic generation and parameter adaptation and an iterative combination of

styles, bears different, emergent properties. The inversion becomes a form of

restoring a new form of aura in the digital world not based on material

originality but rather on algorithmic individuality Leong (2025).

In

order to put

this transformation into context, Figure 2 shows the difference between

the linear and material workflow of traditional printmaking and the iterative

and computational nature of AI-driven printmaking. The latter is a continuation

of manual drawing to engraving, ink, and pressing, and focuses on physical

interaction and dissimilarity between editions. The latter is curating

datasets, pre-processing, neural fusion, aesthetic critique, and digital

printing with an algorithmic feedback and parameter optimization in each step.

The figure highlights a paradigmatic change Leong (2025): the repetition of codes is

based on the craft, the regeneration of the works is based on the code, as both

the human and the machine determine the artistic process. The comparative model

highlights the redefinition of AI of the temporal, material and epistemic

aspects of printmaking Song et al. (2023). It becomes a process of

iteration and translation between art history, computational intelligence and

cultural contextualization, what was previously a linear art craft that was

rooted in surface and pressure.

3. Design Methodology: AI Style Transfer for Printmaking

The

technology of digital printmaking through AI is based on the methodological

framework of Neural Style Transfer (NST) is a computational approach that

combines the content of an image with the style of another to create a hybrid

composition. In printmaking, this operation renders artistic interpretation

mathematically tractable, visual aesthetics are broken down in an artificial

manner into quantifiable expressions of texture, color

and form. The artist plays a role of co-creator, of course, outlining the

conceptual and algorithmic rules of stylistic fusion Ge et al. (2022). The process of work starts

with curation of content and style images. The structural composition is

delivered by the content image, and the visual texture and the painterly

identity is added to this composition by the style image. The two have a set of

preprocessing activities including resolution normalization, colour correction,

feature alignment. To generate structural and stylistic-coded feature maps in a

high-dimensional space, a convolutional neural network (usually a pre-trained

VGG-19) is utilized to extract feature maps at various layers Sun et al. (2022). The mathematical equation of

NST is:

![]()

where:

·

![]() preserves spatial and semantic

structure,

preserves spatial and semantic

structure,

·

![]() ensures stylistic texture

alignment through Gram matrices,

ensures stylistic texture

alignment through Gram matrices,

·

Ltv

represents total variation loss, promoting smoothness and reducing pixel-level

noise, and

·

![]() weighting coefficients

controlling the relative importance of each component.

weighting coefficients

controlling the relative importance of each component.

The

process of optimization can continue using gradient descent until the desired

level of convergence is achieved, at which point the resulting image will trade

the structural clarity that the artist wants with the expressive fluidity of

the selected style. This process is, in its iterative form, aesthetically

regulated by making changes to weights shift the balance between style and

content in the perceptions, making extensive overpages

as well as uprooting visual motifs.

Figure 3

Figure 3 AI Style Transfer Workflow for Digital Printmaking*

When

the digital image attains visual consistency, it is then passed through the

print preparation which constitutes gamut mapping, ICC color

calibration and texture simulation of particular substrates

like canvas, metallic foil or textured paper as shown in Figure 3. The last output fuses the

computational fidelity with the printmaking materiality such that the digital

artifact can be seen as having a physical existence which is in line with

traditional artistic tenets. These parameters, combined with each other, can

enable artists to generate aesthetic results mathematically, where neural

weights are considered tools of creative expression similar to the use of inks

and pigments Yuan and Zheng (2023), Zhang et al. (2024). This is what the methodology

of the AI-based style transfer shifts algorithmic computation into a different

kind of the artisanship of style, a type of digital intelligence/human

intentions convergence, which expands the expressive capabilities of printmaking.

4. Experimental Workflow

The

AI-based digital printmaking experimental workflow attaches to the creative

system of artistic curation, computational modeling,

and materialization as a single system. It is a process that builds upon the

traditional printmaking methodologies to incorporate algorithmic intelligences

at each step of input choice, as well as, to the tactile output. It is not

about copying the existing forms of art but a synthesis of new aesthetic

manifestations by controlled combination of sets of content and style. To accomplish

every step in the workflow, there is to be a process of iteration, balancing

both the artistic vision and computing accuracy so that the final print would

have both creative originality and technical quality Ho et al. (2020). It starts with data curation,

during which images of content and style are taken in order to reflect the

intended thematic and visual range. Content images contain photos, computer

drawings, or scanned drawings that can give structural features whereas style

images contain historical prints, paintings or folk art

motifs that give the texture, color range and surface

action. Such images undergo image size adjustment, normalization, and

preprocessing to have a consistent color balance and

aspect ratios. The curatorial intention of the artist is a key factor to align

the degree of abstraction and aesthetic feeling to be attained throughout the

style transfer.

The

second step is model configuration, involving the use of a deep learning

network which in most cases is a pre-trained VGG-19 or ResNet-50 network

modified to produce artistic style. The algorithm obtains multiscale feature

maps, calculates Gram matrices to measure the patterns of stylistic

correlations. The total loss is minimised by the optimization process.

![]()

In

order to

create perceptual harmony, parameter adjustments (Table 3) are done in real time to

assure that stylistic textures do not corrupt the underlying content structure.

Artists can go through several experiments, storing the intermediate progresses

in order to test a visual consistency, brush density, and the accuracy of the color. Refinement and evaluation stage involves

quantitative and qualitative evaluation Kerbl et al. (2023). The Style Fidelity and content

integrity is measured using the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Perceptual

Loss, and Cultural Authenticity Score (CAS). Side by side comparisons are made

to ensure visual judgments and this enables artists and curators to make

aesthetic judgments as to whether the texture is realistic, compositional

equilibrium, and cultural resonance. These repeated evaluations are a

progressive feedback process that keeps on enhancing the performance of the

models.

5. Comparative Case Studies: Style Adaptation across Cultural Motifs

Even

the style transfer in digital printmaking exploration can reach its

full-fledged significance when it is implemented in regard to the culturally

diverse visual traditions. The neural algorithms can be sensitively programmed

to encode the regional patterns, surface patterns, and symbolic rhythms into

novel hybrid patterns that continue the existing life lineage of traditional

art. In this section three comparative case studies will be given on how neural

style transfer (NST) can reinterpret unique cultural aesthetics Indian

Madhubani, Japanese Ukiyo-e, and European Cubist motifs into digital prints

that are reimagined. Every of the cases indicates another form of interaction

between cultural background and computational synthesis, and AIs can become a creative

collaborator in the development of the artistic identity.

Case Study 1: Indian Folk Art

(Madhubani) and Modern Geometry

In

this experiment, the stylistic background of Madhubani painting of the Mithila

region of India with its rhythmic symmetry, floral patterns, and mythological

patterns was combined with the minimalist line drawings of geometric forms.

Madhubani dataset was used to obtain the style and digital geometric sketches

were used as content inputs. The resulting prints exhibited a perfect

combination of both the classical decorative complexity and the contemporary

reductionism in space.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Case Study 1 Madhubani–Geometric Fusion |

||||

|

Parameter |

Description |

Value / Setting |

Observation |

Interpretive Note |

|

Content Image |

Geometric line sketches, vector forms |

12 images (1024×1024 px) |

Provided structural clarity |

Enhanced pattern legibility |

|

Style Image Source |

Hand-painted Madhubani artworks (floral and mythic

themes) |

25 scans (600 DPI) |

Rich symbolic texture |

Folk rhythm internalized |

|

Model Architecture |

VGG-19 CNN |

Layers Conv4_1, Conv5_1 for style |

Balanced texture fidelity |

Optimal mid-layer representation |

|

Weights |

(alpha = 1.0, \beta = 400, gamma = 0.005) |

High style dominance |

Generated ornate, cohesive fusion |

Folk pattern dominates geometry |

|

Iterations |

1200 |

Smooth convergence |

Strong edge integrity |

Minimal color noise |

|

Output Resolution |

4000 × 4000 px |

High print fidelity |

Texture preserved |

Suitable for large prints |

|

Evaluation Metrics |

CAS = 0.87, SSIM = 0.89, Perceptual Loss = 0.09 |

High cultural resonance |

Stylistic rhythm respected |

Achieved computational homage |

Cultural

Authenticity Score (CAS) and Structural Simililarity

Index (SSIM) were used to assess color fidelity and

pattern coherence and both scored high (CAS = 0.87, SSIM = 0.89). What curators

called the algorithmic homage the model represented the pulse of the Madhubani

without imitation, enjoying its folk rhythm using subordinated abstraction.

Case

Study 2: Japanese Ukiyo-e Textures Translated into Metallic Prints

In

the second instance the interest was to bring the Japanese Ukiyo-e a

traditional method of woodblock printing to the metallic brightness of modern

digital images. The dataset of the style was composed of the high-resolution

scans of Ukiyo-e prints of the Edo period, the inputs of the content were

photographs of the contemporary skyline and seascape. Conv3_1-Conv5_1

Multi-layer Gram matrix fusion has been used in the NST model to model layered

inking. Table 5B below is a summary of the data and the results of this

cross-temporal adaptation.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Case

Study 2 Ukiyo-e Metallic

Transformation |

||||

|

Parameter |

Description |

Value / Setting |

Observation |

Interpretive Note |

|

Content Image |

Urban skylines and seascapes |

18 photos (1920×1080 px) |

Offered tonal diversity |

Enabled gradient modeling |

|

Style Image Source |

Edo-period Ukiyo-e prints |

30 high-res scans |

Complex ink layering |

Captured woodblock tonality |

|

Model Architecture |

VGG-19 (multi-layer Gram fusion) |

Conv3_1 → Conv5_1 |

Maintained cross-scale texture |

Simulated layered pigment |

|

Weights |

( \alpha = 1.0, \beta = 300, \gamma = 0.008 ) |

Balanced stylization |

Retained clarity |

Highlighted brush transitions |

|

Printing Method |

UV-curable pigment on aluminum foil |

2880 × 1800 DPI |

Reflective tactile surface |

Mimicked relief inking |

|

Evaluation Metrics |

PRI = 0.91, Style Fidelity = 0.94, Perceptual Loss

= 0.08 |

High realism |

Enhanced light interplay |

Achieved near-physical tactility |

|

Curatorial Feedback |

5 reviewers, avg. 4.6/5 |

Positive aesthetic judgment |

“Digital relief illusion” |

Reflective realism praised |

On

metallic aluminum foil, the optimization was done and

after that, the UV-curable pigment printing was used to print the outputs,

resulting in a reflective, relief-like finish. According to the curators, the

created images created a visual representation of the tactile experience of

carved wooden grain and pigment saturation as used in traditional woodblock

prints. The Perceptual Realism Index (PRI = 0.91) and Style Fidelity (0.94)

were used to determine the ability of the model to model the experience of

realism based on the computation of the model to produce a tactile feeling

quantitatively.

Case

Study 3: European Cubism and Global Hybridization

The

third work was on transcultural synthesis, joining the European Cubism

abstraction to the African and South Asian textile patterns. It was to be an

interpretive form of bridge between modernist form and the indigenous

ornamentation. The dataset consisted of scanned pieces of Cubists and 40

textile patterns around the world.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Case

Study 3 Cubist–Textile Hybridization |

||||

|

Parameter |

Description |

Value / Setting |

Observation |

Interpretive Note |

|

Content Image |

Abstract still lifes

(Cubist framework) |

10 images (2048×2048 px) |

Provided geometric scaffolding |

Retained form integrity |

|

Style Image Source |

Global textiles + Cubist fragments |

40 images |

Varied chromatic density |

Encouraged hybrid forms |

|

Model Architecture |

CLIP-guided NST |

Semantic conditioning active |

Maintained meaning coherence |

Textural hybridity achieved |

|

Weights |

( \alpha = 1.0, \beta = 250, \gamma = 0.005 ) |

Balanced stylistic control |

Controlled abstraction |

Sustained readability |

|

Iterations |

1500 |

Stable output |

Good pattern fusion |

Strong form–texture unity |

|

Printing Method |

Dye-sublimation on silk blend |

1440 × 720 DPI |

Soft tactile finish |

Maintained tonal elegance |

|

Evaluation Metrics |

CAS = 0.83, SSIM = 0.86, Style Fidelity = 0.92 |

High coherence |

Cultural hybridity expressed |

Semantic clarity preserved |

The

digital prints resulted in fragmented geometric planes superimposed with woven

motifs with a visual texture that was composed of layers that were symbolic of

the globalized aesthetics. The tonal diffusion when printed using the

dye-sublimation method on silk fabric gave the impression of the structure of

analytical cubism and a feeling of the softness of traditional printing on

fabric. The Style Fidelity (0.92) and CAS (0.83) were the results of successful

synthesis of styles without cultural misrepresentation.

Madhubani

-Geometric series is the folk rhythm combined with sacredness to modern

abstraction; the Ukiyo-e Metallic prints are the material translation and

simulated touch; and Cubist-Textile hybrids are the transcultural integration

as the evolution of the algorithm. The two of them create a new paradigm: AI is

used as a cultural interpreter, and digital printmaking becomes a means of

communication between the memory and modernity, tradition and technology.

6. Discussion and Analysis: Ethical and Curatorial Dimensions

Figure 4

Figure 4 Shared Creative Agency Across Conceptual,

Aesthetic, and Material Domains

The

intersection of artificial intelligence and digital printmaking challenges has

impacted all of the traditional practices of authorship, authenticity, and

cultural ownership. The triadic ecosystem artist, algorithm, and culture play a

part in the creative process that provides its own understanding of the final

print in terms of agency. The human artist, the human curator, the human

algorithm and the human source of culture symbolize, generate and give form,

respectively. In such situations where algorithms gather knowledge of past

traditions like Madhubani or Ukiyo-e, they recycle patterns in an abstraction,

and a hybrid form is generated which preserves and redefines cultural content.

It follows that ethical authorship entails cultural reciprocity in that the

source communities are credited, and co-curation or benefit-sharing whenever

the inclusion of traditional art forms in the computational workflow. This

recognition makes AI a manipulation of appropriation into a means of cultural

exchange and creative empathy. The curatorial practice is no exception, but it

also transforms into the mediation of the human and machine art. The visual

result as well as the computational model behind it have been decoded by

curators as a visual result and is commonly recorded in exhibition records as

provenance of the dataset, model design, and algorithm parameters. Such

transparency transforms the notion of authenticity, which is anchored on

material distinctiveness, to traceability in the processes. Every AI generated

print is a computational event that is reproducible but verifiable by metadata

trails or blockchain certificates containing records of the unique generative

parameters. In this regard, authenticity is procedural and not object-based.

In Figure 4. We have plotted the grouped

bar chart that depicts the distribution of creative agency along the

printmaking pipeline. The conceptual phase is dominated by human artists, who

control everything with the intent and vision, whereas AI models gain power over

time in the course of aesthetic synthesis and material translation. However,

the number of cultural sources is less, but they give the symbolic grammar that

informs stylistic learning. The figure highlights the non-hierarchical creative

process in which the three agents mutually influence the results an embodiment

of collective authorship in the work of computational art.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Ethical

Governance Profile in AI Printmaking

The

chart that is presented in Figure 5, points out the strengths and

weaknesses in the proposed ethical framework with respect to the development.

Data provenance scores and aesthetic diversity scores are high, which indicates

good management of datasets and inclusivity, and the scores are low in

transparency, which is an indicator of problems in the curatorial work. The

visualization highlights that AI printmaking needs to be ethically robust,

which involves constant assessment on the interconnected fields, which supports

the connection between the technological design and the cultural

responsibility.

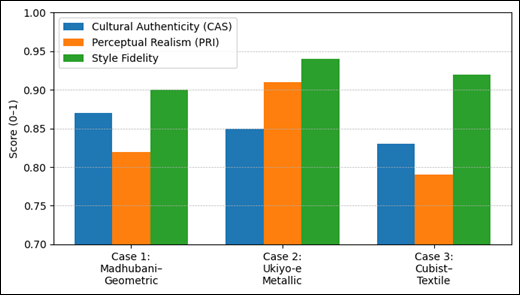

Figure 6

Figure 6 Comparative Evaluation of Cultural Style

Adaptation

The

bar chart in Figure 6 depicts the grouped performance

of aesthetic in experiments that are culturally different. Ukiyo-e Metallic

case had the highest perceptual realism (PRI = 0.91), which is an example of

simulating the tactile experience of layered woodblock prints. The Madhubani-Geometric

fusion was highest in the area of cultural authenticity (CAS = 0.87) showing

folk rhythmicity is preserved. In the meantime, the Cubist-Textile hybrid

recorded better style fidelity (0.92), which verified even integration of

aesthetics. Together, the image shows that the algorithmic style transfer can

keep the culture intact and create an opportunity to diversify the creativity

by working across materials and style.

7. Conclusion

The

paper confirms that AI-inspired digital printmaking is a critical revolution in

the modern art world that blends algorithmic smartness and culture to form a

new paradigm of co-authorship. Neural style transfer permits the motifs,

textures, and aesthetic vocabularies propagated in a part of the brain to be

transferred to new hybrid manifestations, without losing the symbolic echo of

their sources. Incorporating the human instinct and computational synthesis,

and the material embodiment, AI printmaking not only expands the creative

process beyond human craftsmanship but adds the dynamic and iterative

collaboration between the artist, algorithm and culture. Ethically, the

framework highlights such aspects as cultural reciprocity, authorship

transparency, and dataset accountability. The identification of the algorithm

as a creative intermediary and not a neutral tool requires the documentation of

the data provenance, model settings, and stylistic origins by the curators and

artists. This would turn the authenticity into an immobile material object into

a traceable creative operation, so that digital originality will be ethically

accountable. Curatorially, AI printmaking disrupts the definition of the

exhibition space as an interpretive interface due to its aloofness between

algorithms, artwork, and audiences that reflexively interact. The proposed

models of governance exemplified by comparative case studies and ethical

metrics show how the curatorial oversight can be developed to promote

inclusivity and preserve the cultural diversity in the context of algorithmic

creation. Conclusively, AI as a method in print-making is not a diminution of

human creativity but its growth in the form of the computational empathy. It

can be both an instrument of innovation and a site of preservation that crosses

over the borders between heritage and modernity, code and craft, and

imagination and intelligence with the help of ethical awareness and cultural

sensitivity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al-Khazraji, L. R., Abbas, A. R., Jamil, A. S., and Hussain, A. J. (2023). A Hybrid Artistic Model Using DeepDream Model and Multiple Convolutional Neural Network Architectures. IEEE Access, 11, 101443–101459. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3312245

Elgammal, A., Liu, B., Elhoseiny, M., and Mazzone, M. (2017). CAN: Creative Adversarial Networks Generating “Art” by Learning About Styles and Deviating From Style Norms. arXiv Preprint.

Gatys, L. A., Ecker, A. S., and Bethge, M. (2015). A Neural Algorithm of Artistic Style. arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.06576

Ge, Y., Xiao, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, X., and Itti, L. (2022). Contributions of Shape, Texture, and Color in Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 369–386, Tel Aviv, Israel. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19815-1_21

Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., and Bengio, Y. (2020). Generative Adversarial Networks. Communications of the ACM, 63, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1145/3422622

Hicsonmez, S., Samet, N., Akbas, E., and Duygulu, P. (2020). GANILLA: Generative Adversarial Networks for Image-to-Illustration Translation. Image and Vision Computing, 95, 103886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imavis.2019.103886

Ho, J., Jain, A., and Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 6840–6851.

Isola, P., Zhu, J.-Y., Zhou, T., and Efros, A. A. (2017). Image-to-Image Translation With Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (1125–1134), Honolulu, HI, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.632

Kerbl, B., Kopanas, G., Leimkühler, T., and Drettakis, G. (2023). 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 42, 139:1–139:14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3592433

Leong, W. Y. (2025). AI-Generated Artwork as a Modern Interpretation of Historical Paintings. International Journal of Social Science and Artistic Innovation, 5, 15–19.

Leong, W. Y. (2025). AI-Powered Color Restoration of Faded Historical Painting. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Digital Arts, Media Technology (DAMT) and the 8th ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (NCON), 623–627, Nan, Thailand.

McCormack, J., Gifford, T., and Hutchings, P. (2019). Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art. In Proceedings of EvoMUSART: International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art, and Design (pp. 35–50). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16667-0_3

Song, Y., Qian, X., Peng, L., Ye, Z., and Tan, J. (2023). Cultural and Creative Design of AIGC Chinese Aesthetic. Packaging Engineering, 44, 1–8.

Sun, Q., Chen, Y., Tao, W., Jiang, H., Zhang, M., Chen, K., and Erdt, M. (2022). A GAN-Based Approach Toward Architectural Line Drawing Colorization Prototyping. The Visual Computer, 38, 1283–1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00371-021-02278-8

Tan, W. R., Chan, C. S., Aguirre, H. E., and Tanaka, K. (2016). Ceci N’est Pas Une Pipe: A Deep Convolutional Network for Fine-Art Paintings Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP) (pp. 3703–3707), Phoenix, AZ, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP.2016.7533051

Yuan, C., and Zheng, H. (2023). A New Architectural Design Methodology in the Age of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Architectural Journal, 10, 29–35.

Zhang, A., Wang, S., Zhang, D., and Ji, D. (2024). Gene Extraction and Intelligent-Assisted Innovative Design of Nanjing Architecture in the Republic of China Period. Packaging Engineering, 45, 302–314.

Zhu, J.-Y., Park, T., Isola, P., and Efros, A. A. (2017). Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2223–2232), Honolulu, HI, USA. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.244

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.