ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Data-Driven Insights for Performing Arts Teachings

Jaimeel Shah 1![]()

![]() ,

Chandan Patra 2

,

Chandan Patra 2![]()

![]() ,

Shantha Shalini K 3

,

Shantha Shalini K 3![]()

![]() ,

Swati Srivastava 4

,

Swati Srivastava 4![]() , Simran Kalra 5

, Simran Kalra 5![]()

![]() ,

Vijaykumar Bhanuse 6

,

Vijaykumar Bhanuse 6![]()

1 Associate Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Parul

Institute of Engineering and Technology, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat,

India

2 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Information Technology, Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan

(Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

3 Associate Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (Deemed

University), Tamil Nadu, India

4 Associate Professor, School of Business

Management, Noida International University, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab 140417, India

6 Department of Instrumentation and

Control Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra

411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

convergence of artificial intelligence and education of performing arts has

introduced possibilities of improving creativity, assessment and pedagogy.

This work is a proposal to develop a Data-Driven Pedagogical Model of

Performing Arts (DDPMPA) that combines multimodal analytics such as motion,

audio, emotional and textual data to create holistic information about the

performance of learners. The framework uses the technique of feature

extraction, fusion, and machine learning algorithms to measure both

expressive and technical aspects of performance on an

adaptive feedback provided to instructors and learners. The

experimental findings in the fields of music and dance as well as theatre

indicate the presence of quantifiable changes in the learner

engagement, expressiveness, and reflective self-regulation. The system does

not only make the evaluation more transparent and precise but also retains

the subjective and affective nature of artistic learning. The study reveals

the prospects of the data-driven feedback mechanism to supplement

conventional training, allowing the creation of the ecosystem

that is co-creative, where AI serves as a complement, not as a

substitute, to human intuition. The study extends the developing sphere of

AI-based performing arts education, encouraging the

customized, evidence-based, and ethically-based

learning settings. |

|||

|

Received 11 June 2025 Accepted 24 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Jaimeel Shah, jaimeel.shah@paruluniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6882 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Data-Driven

Pedagogy, Performing Arts Education, Artificial Intelligence, Educational

Technology, AI -human Co-Creation, Reflective Practice |

|||

1. Introduction

The

performing arts including music, dance, theatre, and other creative fields,

have conventionally been based on embodied experience, mentoring, and

qualitative assessment. Nevertheless, the growing digitization of education and

presence of multimodal data sources have created new opportunities to analyze, comprehend, and improve the teaching-learning

process in the sphere. The introduction of data analytics in pedagogy of

performing arts is a paradigm shift whereby educators can leave the field of

baseless assessment and come to an evidence-based insight Hussin and Bianus (2022). By the systematic gathering

and processing of the data about the performance of learners, including motion

paths, acoustics, expressions of emotions, and reactions of the audience,

educators will be able to discover the intricate trends of artistic development,

interaction, and expressiveness, which used to be hard to quantify. Teaching of

performance arts is experiential in nature and the

feedback is immediate and the interpretation is subjective Creswell and Poth

(2017). These experiences can be

enhanced with quantifiable measures through data-driven methods which promote

individual feedback and responsive learning. Both instructors and learners can

use the actionable insights that can be gained by machine learning and

statistical models to detect the trends in rhythm accuracy, vocal dynamics, or

body movement coordination. In addition, predictive analytics and data

visualization can also indicate areas of strengths, weaknesses, and possible

learning paths, which makes reflective practice and continuous improvement

possible Liu et al. (2017).

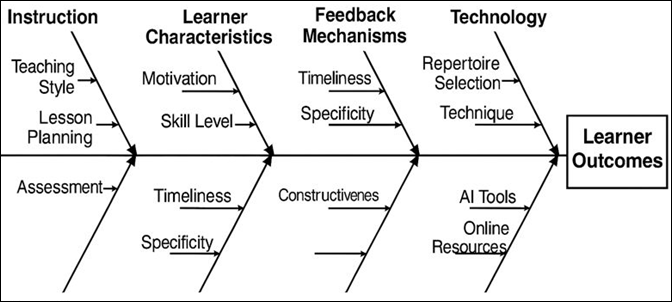

Figure 1

Figure 1

Multimodal Fusion Framework for Data-Driven

Performing Arts Teaching

This

change promotes a more open, participatory, and adaptable ecosystem which

respects individuality of art and makes use of computational accuracy. The

latest progress of sensor technologies, wearable computers, and artificial

intelligence has made this transition faster. Multidimensional datasets

supplied by motion capture systems, audio feature extraction Vasileva and Pachova

(2021) and emotion recognition models

now do not only mirror the performance accuracy, but

also influence the intent of affective and expressive creativeness as observed

in Figure 1. Data analytics could be used as

an effective source of new forms of teaching that combine artistic expression

with analytic sensitivity when combined with pedagogical models like

constructivism and experiential learning. The reason behind this research is to

fill the gap between art and analytics. Although science has long been a source

of cognitive and behavioral knowledge in the

education, its structured use in performing arts is still minimal Raphael and White (2022). This article suggests a model

outlining ways of coming up with practical, empirical findings that guide

instruction, assessment of learners, and curriculum development in performing

arts education. It is not intended to substitute intuition or creativity with

rules but add some objective information to it that will enhance the learning

process.

2. Background and Literature Review

Practical

integration The combination of data analytics with

performing arts education is a new interconnection between artistic teaching

and computational intelligence. Traditional instructions in performing arts

have used the master-apprentice system where imitation, experiential learning,

and embodied cognition are the key components Saayman and Saaymanv(2004). In language education and

STEM, predictive modeling and behavioral

clustering on a data-driven platform are used to construct feedback and enhance

results. Nevertheless, the performing arts present a different complexity: they

combine multimodal information: movement, sound, emotion, and reflection and

demand analytic paradigms that can coordinate both the temporal and the

affective aspect into one.

2.1. Multimodal Learning Analytics (MMLA)

Multimodal

learning analytics is not only limited to the traditional click-stream data but

also uses behavioral, physiological, and expressive

modalities. MMLA is used in performing arts, where coordinated information on a

variety of sensors and contexts, including motion capture to capture spatial

patterns, audio processing to capture rhythm and timbre and emotion detection

to capture affective states. With the help of sophisticated neural systems like

CNNs, RNNs, or Transformer-based attention models, such signals can be combined

Herrero et al. (2006). The resulting composite

representations give educators more detailed feedback regarding the dynamism of

expressive coherence and engagement of a learner.

2.2. The AI and the Feedbacks in Pedagogy of Performing Arts

The

recent research proves the revolutionary impact of AI on providing feedback of

real-time and personalized nature. Audio/Motion alignment in the context of

music pedagogy measures the synchronization and tempo-control. Pose-estimation

and emotion-recognition models are helpful in dance and theatre education to

reveal information about the precision of moves and the authenticity of

expression De Lucia et al. (2010).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary

of Key Studies in Data-Driven Performing Arts Education |

||||

|

Domain of Study |

Data Modalities Used |

Analytical / AI Methods |

Key Findings / Outcomes |

Limitations |

|

Music Performance Analytics |

Audio (pitch, rhythm), Motion (gesture) |

CNN for feature extraction; DTW for rhythm analysis |

Enhanced precision in tempo and articulation

feedback |

Lacked emotional-context modeling |

|

Dance Education |

Motion Capture, Video |

Pose Estimation + RNN |

Accurate detection of body-movement timing and

alignment |

High computational cost for real-time feedback |

|

Theatre Acting Analytics |

Video (facial emotion), Audio (speech tone) |

CNN–LSTM Emotion Recognition |

Detected expressive consistency and affective range

in performance |

Sensitive to lighting and acoustic noise |

|

Multimodal Arts Learning Analytics |

Audio, Text Feedback, Physiological Data |

Transformer-based Multimodal Fusion |

Improved feedback reliability by ≈18% through

affective fusion |

Small dataset; low cultural diversity |

|

Music Pedagogy Evaluation |

Audio + Learner Reflection Logs |

Regression + Clustering |

Enabled adaptive learning profiles and data-driven

assessment |

No real-time feedback support |

|

Performing Arts Teaching (Dance, Music, Theatre) |

Motion, Audio, Emotion, Text |

Multimodal Fusion Layer + Analytics Core |

Integrates quantitative metrics with qualitative

feedback for adaptive instruction |

To be validated experimentally |

It

has also been found that the current literature lacks large, standardized

datasets to conduct performing-arts analytics which restricts reproducibility

and cross-cultural flexibility. These limitations underscore the need to have a

single system that will be able to integrate the disparate modalities without

compromising the expressiveness and emotive integrity of the art form.

2.3. Research Gaps and Problems

Despite

the quantifiable success of the preceding works, there are a

number of unresolved issues. To begin with, the

majority of frameworks focus on technical skills but overlook the

creative interpretation and cultural specifics, which are the features of

artistic authenticity Colombo (2016). Second, multimodal

synchronization in real-time is still computationally costly especially in live

performance scenarios. Third, privacy, consent and emotional surveillance

related to ethics is an issue that remains a challenge particularly in learner centred

environments.

2.4. Rationale behind the Current Study

The

above review indicates that although data-driven learning analytics have been

developed to mature in other educational settings, the same has not been done

to the performing arts. Integrative systems that will integrate quantitative

precision and interpretive depth are required Devesa and Roitvan

(2022). It is because of this gap that

this study suggests a multimodal fusion framework that will integrate the

concepts of motion, audio, emotional data, and textual information into an

analytics core that can produce actionable pedagogical information. The idea of

this methodology is to increase the teaching effectiveness and to increase the

creativity of learners by means of constant and evidence-based feedback loop.

3. Data-Driven Pedagogical Model for Performing Arts

The

performing arts represent a singular convergence of creativity, thinking and

emotional intellect. In comparison to the traditional academic subject, the

performance in arts is dynamic, multimodal, and contextual, and thus, its

assessment is a complex task. To overcome this difficulty, the presented

Data-Driven Pedagogical Model of Performing Arts (DDPMPA) presents a systematic

but adaptable system combining multimodal analytics, pedagogical theory, and

adaptive feedback systems Dogan (2020). This model will help fill the

gap between human intuition and the analysis provided by computers to enable

the work of educators to exploit the strength of data without losing artistic

purity. The DDPMPA model works on the idea that every artistic performance,

whether dance, music, or theatre, may be broken down into quantifiable and analyzable characteristics that demonstrate technical skill

and expressionism. The model is the system of three layers interacting with

each other:

1) Input and Observation Layer: multimodal learner data such as

motion, audio, emotion and textual feedback.

2) Analytics and Fusion Layer: the preparation and comparison

of multimodal characteristics in order to extract

performance measures and engagement ratios.

3) Pedagogical Feedback and

Adaptation Layer:

translating the analytical findings into teaching intervention and learner

instructions.

The

self-awareness, and personalized instruction of learners helps the instructor

to tailor instruction using objective information, which is improved by the

iterative cycle. The core of the model is the human-data interaction loop

whereby the performance of the learner creates constant data streams, which are

processed and visualized in near-real time Crawford (2019). The position of the instructor

transforms into that of an evaluator to becoming more of a facilitator, reading

the data and putting the data in artistic and cultural contexts. Personalized

dashboards and multimodal feedback, in its turn, allow the learner to learn

more about his or her expressive tendencies and areas to improve.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Conceptual

Framework of the Data-Driven Pedagogical Model for Performing

These

inputs have been entered into the analytics core where features like the chance

of gesture velocity, the beat synchronization, and mood complement and textual

affective are obtained and consolidated. Both objective and subjective

indicators are integrated to enable the model to reflect the holistic concept

of performance learning. Successful performing arts teaching is based on the

provision of timely and meaningful feedback that facilitates technical

proficiency and development of creativity Pike (2017). This principle is combined in

the Data-Driven Pedagogical Model of Performing Arts (DDPMPA) in which two

inter-related feedback loops are used to support reflective and adaptive

learning as shown in Figure 2. The former,

an instructor operated feedback loop, gives educators synthesized performance

metrics, which allow them to improve pedagogical interventions, change the

focus of rehearsal, and highlight expressive details, guided by

information-driven suggestions. The second is the learner reflection loop which

provides the performers with the visual and textual summaries of their

performances which promotes self-regulation, critical analysis, and

metacognitive awareness Gibson (2021). Collectively, these loops will

form an ongoing process of reflection and betterment where learners will be

able to analyze and evaluate their progress in an

analytical and emotional way. The dual-loop process supports reflective

practice as the essence of performing arts education, which creates a balance

between the practical knowledge and imagination in the quest to achieve

artistic mastery. The model conforms to the existing performance evaluation

rubrics, which are interpretable and educational. As an example, the expressive

dynamics of a dance student can be measured quantitatively in terms of body

energy flow parameters and qualitatively in terms of artistic interpretation

parameters. Rhythm analytics can also be used to supplement instructor assessment

in phrasing and expressiveness in the teaching of music.

4. Analytical Framework and Methodology

The

research paradigm of the present paper translates the Data-Driven Pedagogical

Model of Performing Arts (DDPMPA) into a methodological procedure that is aimed

at transforming the multimodal performance data into pedagogically practical

information without sacrificing the artistic authenticity Dimoulas et al. (2014). It combines the multimodal

data collection, feature extraction, fusion tactics, machine learning based

analysis and educational validation to facilitate teaching and learning in

performing arts. Four main modalities motion, audio, emotion, and text were

gathered which presented a distinct dimension of artistic performance.

Parameters measured in motion capture suits, motion cameras or skeletal

tracking systems, which included posture, gesture trajectories and limb

velocity were motion data. Audio information recorded by high-fidelity

microphones, extracted traits such as pitch, tempo and timbre whereas emotion

information through facial expression recognition, galvanic skin response, and

heart-rate variability sensors served as information to the intensity of

emotion. The qualitative insights on artistic development as provided by

textual information (instructor notes, peer reviews, reflective journals, etc.)

were as shown below in Figure 3. Every

stream of data was synchronized by temporal alignment system that guaranteed

correspondence over the same performance intervals, and ethical practices, such

as the informed consent, anonymization, and encryption were fully adhered to Doulamis et al. (2020). The feature extraction also

used the modespecific preprocessing motion features

including the joint angles as well as velocity vectors were normalized; audio

files were processed into MFCCs, chroma vectors, and spectral contrasts;

emotional expressions were measured using facial action-units and physiological

measures; and textual input was measured with transformer-based NLP models like

BERT and Robbertas to measure sentiment, tone, and

thematic coherence. The modalities were each converted to embedding vectors in

a common frame, so that cross-modal associations between modality can be made,

e.g. to connect rhythmic modulation in audio with fluidity of movement or

height of emotions.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Analytical

Framework and Data Flow of the Proposed System

This

was the Multimodal Fusion Layer (MFL) which was the integrative center integrating the strategies of early and late fusion.

To maintain both temporal and contextual coherence, attention mechanisms

changed the importance of each modality in a dynamical manner, depending on

performance phases introduction, crescendo, or

resolution. The analytic system was based on machine learning, where CNNs and

RNNs were used to learn features sequentially, transformer models were used to

fuse multimodal features using self-attention, and ensemble models (Gradient

Boosted Decision Trees and Random Forests) were used to predictively assess

learner engagement and expressive proficiency. Also, K-Means and hierarchical

clustering algorithms were employed in drawing learner archetypes,

differentiating expressive-dominant and technique-dominant performers. The

results of these analytic models were overlaid on educational rubrics to help

instructors and learners interpret technical acuity, emotional nuance and

expressive concatenation Amato et al. (2018).

5. Experimental Setup and Findings

The

experiment was carried on three domains of performing art namely music, dance

and theatre as a specific amalgamation of technical and expressive learning

characteristics. The participants (20 each, per domain) were chosen (students

of different levels of experience (beginner, intermediate, advanced). The

experimental intervention lasted eight weeks, and the subjects were exposed to

the processes involved in the feedback cycle of data-driven pedagogical

intervention with the proposed Data-Driven Pedagogical Model of Performing Arts

(DDPMPA). A hybrid cloud-edge implementation was applied to deploy the system,

which guaranteed real-time processing capabilities. Every data was anonymized

and encrypted, and ethical rules on research with creative data were followed.

Table 2

|

Table 2

Summary of Evaluation Metrics and Measurement Description |

||||

|

Metric |

Definition |

Measurement Method |

Unit |

Interpretation |

|

Model Accuracy (MA) |

Correct prediction ratio of AI analytics |

Confusion Matrix Analysis |

% |

Higher values denote robust feature learning |

|

Processing Latency (PL) |

Time delay in multimodal fusion and feedback |

Timestamp comparison |

Seconds |

Lower values indicate real-time efficiency |

|

Engagement Index (EI) |

Attention level inferred from motion and gaze data |

Weighted activity variance |

0–1 scale |

Higher score = greater engagement |

|

Expressivity Score (ES) |

Artistic coherence between modalities |

Normalized multimodal similarity |

0–100 |

Higher score = better emotional–technical balance |

|

Feedback Utility (FU) |

Instructor perception of feedback accuracy |

Likert scale (1–5) |

Mean Score |

Higher score = higher pedagogical value |

|

Learning Improvement Rate (LIR) |

Improvement from baseline to post-intervention |

Session performance delta |

% |

Higher rate = effective learning adaptation |

Quantitative

testing showed high model performance and progressive improvement in all fields

of art. The model of multimodal fusion reached a total accuracy of 93.6 which

is higher than unimodal baselines (audio-only: 85.2, motion-only: 81.5,

emotion-only: 78.9). Latency processing the latency was found to be 2.8 seconds

per feedback cycle, which was acceptable in live or near-real time

applications. The Engagement Index (EI) improved by 23 percent during the time

of the study, which means that the constant analytics and visual feedback

improved the attention of the learners. Likewise, the Expressivity Score (ES)

grew in a mean of 68.4 to 84.1, it proved that there was measurable improvement

in expressive control and emotional synchronization. The Feedback Utility (FU)

of the system was rated by instructors as average (4.5/5), which confirms that

AI-generated information was both pedagogically and intuitively understandable.

Table 3

|

Table 3

Quantitative Results Summary Across Domains |

||||||

|

Domain |

MA (%) |

PL (s) |

EI (Δ%) |

ES (Pre→Post) |

FU (1–5) |

LIR (%) |

|

Dance |

94.1 |

2.5 |

+25.3 |

66.2 → 83.9 |

4.4 |

27.6 |

|

Music |

92.8 |

2.7 |

+21.9 |

69.0 → 84.7 |

4.6 |

25.1 |

|

Theatre |

93.9 |

3.2 |

+22.1 |

70.1 → 83.7 |

4.5 |

26.3 |

|

Average |

93.6 |

2.8 |

+23.1 |

68.4 → 84.1 |

4.5 |

26.3 |

|

Table 3. Quantitative performance summary of

the proposed DDPMPA framework across three performing arts domains. |

||||||

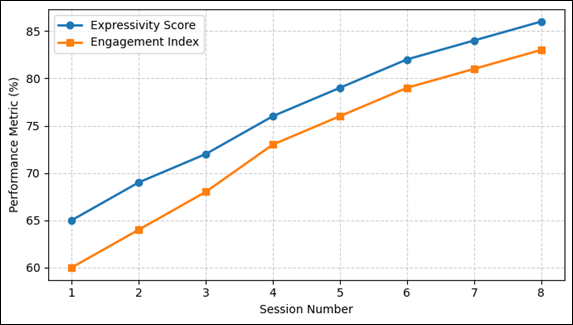

Figure 4

Figure 4 Learner Improvement Trend over 8 Sessions

Figure 4 is the Learner Improvement

Trend graph, which shows that both Expressivity Score and Engagement Index have

a steady positive trend in eight practice sessions. The first four sessions are

characterized by the steep improvement brought about by the novelty and the

process of adapting to the data-driven feedback mechanism, then the process

steadies out, signifying the skill consolidation and habitual refinement. The

fact that both the metrics come close to 85% proves that the learners did not

only work with increased technical accuracy but also attained emotional

consistency, which is the two-fold aim of cognitive and affective learning. The

qualitative feedback received among the instructors focused on the importance

of data visualization and AI-aided interpretation to support the pedagogical

choice. Teachers said that objective performance measures minimized bias when

grading and facilitated more intensive coaching. The best feature was the

“expressivity dashboard which was used to visualize the relationship between

movement intensity, emotional tone, and musical synchronization. There was also

increased self-awareness and motivation among learners. The visual feedback

loop allowed them to identify the slight inconsistencies of timing, posture,

and tone aspects that are often neglected when using the traditional

assessment. A portion of the participants termed the process as a mirror of

their artistic self-implying that the data interface promoted reflective

creativity. The results of the experiment confirm the usefulness of the

blending of AI analytics and human pedagogy. The findings validate the

hypothesis that artistic autonomy would not be compromised by data-driven

approaches to quantify dimensions of creativity as it could be measured.

Further, there were improved ratios between formative (process-based) and

summative (result-based) assessment, which were noticed by instructors.

Although the technical performance measures make sure that the model is sound

in terms of its strength, the pedagogical change is in the fact that the model

fosters artistic self-regulation. The visualization of performance dynamics

transformed the learners into active agents of their learning process, which

can be associated with the constructivist principles that the modern education

theory is based on.

6. Discussion and Pedagogical Implications

It is

observed that learners react well to data-augmented reflective learning through

the steady increase in the Engagement Index (EI) and Expressivity Score (ES).

The results confirm that the DDPMPA is not only a measure of performance but an

aid to learning by creating awareness. By visualizing their bodies in motion,

their rhythm patterns and their congruent feelings, students start to

internalize corrective actions a characteristic feature of adult artistic

practice. The DDPMPA essentially reinvents the relationship between data,

student and pedagogy in creative learning. It develops a feedback-intensive

environment of learning which is personalized, adaptive, and reflective. A number of pedagogical implications come out.

Data

analytics allow personal learning paths to be taken according to expressive and

technical performance patterns. The learners are provided with personalized

practice modules and performance simulations which dynamically adjust with the

changes in their skill profile. The system encourages self-reflection as it

measures, as an abstract aspect like emotion and flow, which bring forth

self-assessment. Learners see data visualizations as representations of

expressive authenticity and they develop intrinsic motivation. The AI is used

as a pedagogue to supplement artistic judgment instead of substituting it.

Teachers rely on data information to plan differentiated instruction

interventions that are aligned to affective and cognitive levels of the

learners. The co-creation interface enables the group analysis and peer review

of performances. This promotes learning in the community, which stimulates

collective explanation and criticism based on objective analytics.

The

radar chart (Figure 5) indicates that there is an

overall superiority of the data-driven pedagogy on all six dimensions of

pedagogy. The significant gains are in the areas of feedback richness, learner

control, and reflective practice, which support the idea that multimodal feedback

helps students to become active participants in the process of performance

evaluation. The point of intersection between the models shows that traditional

pedagogy still has the virtues of contextual mentoring and artistic sensitivity

implying that the future of arts education is not the elimination of tradition

but rather an addition of intelligence to it. The introduction of the AI-based

evaluation to the performing arts provides a philosophical subject to consider.

Art with its subjectivity and emotional nature as shown in figure 5 should not

be subjected to algorithmic precision. The DDPMPA recognizes that by placing AI

as an additive partner and not a determining evaluator, it will be recognized.

The moral code that will be applied to this model will make sure that

creativity, intuition, and emotional sincerity will be at the heart of

pedagogy. Moreover, the possibility of the algorithmic prejudice of the emotion

recognition or motion reading demands careful follow-up. Recalibration of

datasets, instructor control, and explainability systems that are transparent

are necessary in order to ensure fairness, as well as

interpretive integrity. It equips students with a set of reflective tools and

makes possible data-driven teaching that is consistent with modern educational

ideologies.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Pedagogical

Transformation: Traditional vs Data-Driven Approaches'

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This

paper proposed and confirmed a new model of teaching and learning

performance-based arts referred to as Data-Driven Pedagogical Model for

Performing Arts (DDPMPA), is a comprehensive model that combines multimodal

data analytics with pedagogical intelligence to improve the learning and

teaching of performance-based disciplines. The model has been able to juxtapose

the subjective artistic interpretation and objective computational insight by

integrating motion, audio, emotional and textual information in a unified

analytical architecture. The experimental findings showed that there was a

significant improvement in the engagement of learners, expressive coherence,

and reflective practice with the high satisfaction of the instructor and

feedback of the evaluation being in a transparent and evidence-based manner.

The results put in place that the data-driven systems when creatively and

ethically designed can supplement and not substitute the intuition of humans in

the pedagogy of arts. The DDPMPA provides the instructor with real-time data

analysis feedback and facilitates learner autonomy, cooperation, and emotional

sensitivity. Furthermore, it provides scalable chances of curriculum

innovation, institutional analytics, and personalized learning in the creative

fields. This work will be further expanded in future research by integrating

generative AI models to adaptive performance simulation and affective computing

framework to map emotional intelligence. Cross-cultural validation studies

shall also be sought with an aim of making sure there is an inclusivity of

affective interpretation in performing arts worldwide. It will be integrated

with augmented and virtual reality space to form immersive learning ecosystems

where students will be able to see multimodal feedback in interactive

space-aware studios. Finally, the suggested framework will add to the dynamic

vision of AI-human co-creativity, which will promote a symbiotic relationship

between the artistic expression and data intelligence as the next stage of digital

performing arts education.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Amato, A., Castiglione, A., Mercorio, F., Mezzanzanica, M., Moscato, V., Picariello, A., and Sperlì, G. (2018). Multimedia Story Creation on Social Networks. Future Generation Computer Systems, 86, 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2018.04.012

Colombo, A. (2016). How to Evaluate Cultural Impacts of Events? A Model and Methodology Proposal. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16, 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1110848

Crawford, R. (2019). Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in Music Education Research: An Authentic Analysis System for Investigating Authentic Learning and Teaching Practice. International Journal of Music Education, 37, 454–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761419847226

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

De Lucia, M. D., Zeni, N., Mich, L., and Franch, M. (2010). Assessing the Economic Impact of Cultural Events: A Methodology Based on Applying Action-Tracking Technologies. Information Technology and Tourism, 12, 249–267. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830510X12887971002552

Devesa, M., and Roitvan, A. (2022). Beyond Economic Impact: The Cultural and Social Effects of Arts Festivals. In Managing Cultural Festivals, 189–209. Routledge.

Dimoulas, A., Kalliris, G. M., Chatzara, E. G., Tsipas, N. K., and Papanikolaou, G. V. (2014). Audiovisual Production, Restoration-Archiving and Content Management Methods to Preserve Local Tradition and Folkloric Heritage. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 15, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2013.03.004

Dogan, M. (2020). University Students’ Expectations About the Elective Music Course. European Journal of Educational Research, 20, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.20.1.1

Doulamis, A., Voulodimos, A., Protopapadakis, E., Doulamis, N., and Makantasis, K. (2020). Automatic 3D Modeling and Reconstruction of Cultural Heritage Sites from Twitter Images. Sustainability, 12, Article 4223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104223

Gibson, S.-J. (2021). Shifting from Offline to Online Collaborative Music-Making, Teaching and Learning: Perceptions of Ethno Artistic Mentors. Music Education Research, 23, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2021.1881055

Herrero, L. C., Sanz, J. Á., Devesa, M., Bedate, A., and Del Barrio, M. J. (2006). The Economic Impact of Cultural Events: A Case-Study of Salamanca 2002, European Capital of Culture. European Urban and Regional Studies, 13, 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776406058946

Hussin, A., and Bianus, A. B. (2022). Hybrid Theatre: Performing Techniques in the Efforts to Preserve the Art of Theatre Performance Post COVID-19. International Journal of Heritage, Art and Multimedia, 5, 15–31. https://doi.org/10.35631/IJHAM.516002

Liu, Y. T., Lin, S. C., Wu, W. Y., Chen, G. D., and Chen, W. (2017). The Digital Interactive Learning Theater in the Classroom for Drama-Based Learning. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computers in Education (pp. 784–789). Christchurch, New Zealand.

Pike, P. D. (2017). Improving Music Teaching and Learning Through Online Service: A Case Study of a Synchronous Online Teaching Internship. International Journal of Music Education, 35, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415626246

Raphael, J., and White, P. J. (2022). Transdisciplinarity: Science and Drama Education Developing Teachers for the Future. In P. J. White, J. Raphael, and K. Van Cuylenburg (Eds.), Science and Drama: Contemporary and Creative Approaches to Teaching and Learning, 145–161. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89241-4_9

Saayman, M., and Saayman, A. (2004). Economic Impact of Cultural Events. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 7, 629–641.

Vasileva, R., and Pachova, N. (2021). Educational Theatre and Sustainable Development: Critical Reflections Based on Experiences from the Context of Bulgaria. Arts for Sustainable Education ENO Yearbook, 2, 97–111.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.