ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Management of Online Art Education Platforms

Priyadarshani Singh 1![]() , Himanshu Makhija 2

, Himanshu Makhija 2![]()

![]() ,

Chaitanya Joshi3

,

Chaitanya Joshi3![]()

![]() ,

S. Balakrishnan4

,

S. Balakrishnan4![]()

![]() ,

Hitesh Singh 5

,

Hitesh Singh 5![]()

![]() ,

Prashant Anerao 6

,

Prashant Anerao 6![]()

1 Associate Professor School of Business Management Noida International University, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Film and Television, Parul Institute of Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

4 Professor and Head, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

6 Department of Mechanical Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Ecosystems of

online art education have become rich online spaces, combining creative

pedagogy and smart technology and data-driven management. The research

explores a global governance and operational system that combines artificial

intelligence and cloud services with ethical policies to provide more

accessibility, quality, and sustainability in the learning of digital art.

The study identifies the use of human-AI hybrids in enhancing the learner

experience, teaching and learning, and organizational effectiveness by

analyzing the stakeholder collaboration, learning outcomes, and risk

management aspects. The model focuses on fair monetization, transparency of

intellectual property management and culturally aware content curation such

that creativity and accountability exist in a safe online space. Analysis of

quantitative performance shows that there are great correlations between the

engagement performance and completion rates, consistent increase in revenue

growth and system reliability which confirms the suggested governance model.

The paper ends with a strategic plan, based on which immersive technologies,

predictive analytics, and blockchain-based accreditation might be integrated

to promote the concept of sustainable and inclusive art education in the

global context. |

|||

|

Received 19 June 2025 Accepted 03 October 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Priyadarshani

Singh, priyadarshani.singh@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6881 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Online Art Education, Governance Framework, Risk

Management, Cultural Sensitivity, Blockchain Accreditation, Immersive

Learning, Creative Ecosystem |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The global educational environment has been transformed by the rapid growth of digital learning environments and art education is not an exception. The online art education platform management has become an important strategic field, which brings pedagogy, technology and creative economics together. Such platforms as institutional learning management systems (LMS) to separate creative marketplaces are vital facilitators of democratising the access to artistic knowledge, acquiring skills and collaborative creativity Pavlou (2022). Over the past few years, high bandwidth connectivity combined with relatively cheap digital devices and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) has changed the way art is taught, critiqued, and monetized. Nevertheless, the operation and maintenance of such platforms are complicated issues, which are associated with pedagogy, governance, intellectual property, and efficiency of operation Sabol (2022). The process of online art education development has been triggered by the increasing need to engage in flexible methods of learning and the international transition of consuming content online Somekh (2007). Contrary to the classroom education with a traditional framework, online art platforms have to support not only a cognitive learning process but also influence other dimensions of the affective and psychomotor engagement essential in creative fields. The necessity of simulating the experience of working in a tactile studio, providing the real-time feedback on the visual work, and ensuring the collaboration with peers introduces complexities in the management, the ones that are not characteristic of other areas of e-learning. Moreover, when these platforms incorporate AI applications to critique images, recreate styles, and evaluate portfolios, the problem of ethical use and creative ownership is getting even more valuable Brumfield Montero (2021), Quinn (2011).

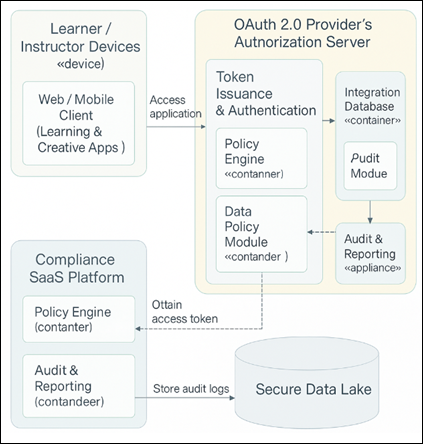

Figure 1

Figure 1 Artistic Style Transfer Pipeline in an Online Art Education Platform

Strategically, the online art education platforms are complex multidimensional ecosystems composed of different stakeholders’ learners, instructors, institutions, content creators, and technology providers as represented in Figure 1 These stakeholders should be aligned under consistent policies to manage the content quality, pricing, accessibility, and intellectual property rights to facilitate its effective management. Another essential feature is the implementation of the data analytics with the strong level of performance monitoring, the tracking of the engagement, and ongoing improvement of pedagogical results Critical Arts Education for Sustainable Societies (CARE/SS). (2024). More informed decision-making has been made possible through the introduction of adaptive algorithms and predictive analytics which are used by the managers of the platforms to identify learning gaps, optimize the delivery of content, and predict the enrollment patterns. This paper will examine the strategic, operational, and technological aspects of operating an online platform of art education, and its broad area will be sustainability growth, user interactions, and policy formulation. It analyzes the models of governance, its monetization, and the impact of emerging technologies on the optimization of platforms Cong, S. (2024), Dai et al. (2022). The paper has been enhanced by the presented proposal of the full management framework, which would combine the pedagogical integrity and technological innovations to guarantee the online art education to be inclusive, scalable, and creatively authentic in the changing digital age.

2. Literature Review

Online education through online art education platforms is managed at the border of educational technology, creative pedagogy and governance of online digital resources. There exists a literature review of how online learning systems have shifted past simple course delivery model systems to more complex ecosystems that can facilitate artistic creativity, criticism, and labour Ezquerra et al. 2022). The shift between the studio based teaching and digital platforms as applied in the context of art education requires the reconfiguring of the pedagogical and managerial structures to adapt to the distinct conditions of artistic practice including its subjectivity, sensuous experience, and feedback Ehtiyar et al. (2019). According to the literature, the systems of online education are excellent at providing the structured cognitive material, but in most cases, fail to reproduce the experiential and affective aspects of art learning. The initial studies of digital art pedagogy (e.g., McLaren, 2017; DeVoss and Ridolfo, 2019) were focused on the transformation of the instructor-oriented teaching approach to the learner-oriented exploration of using multimedia tools. These papers claim that digital classroom should offer participatory learning setting where experimentation and reflection are encouraged instead of simple instruction Pyo (2019). Currently more recent studies have dwelled on the constructivist and experiential learning models adapted to creative disciplines with the emphasis to project-based assessment, peer feedback, and live critique setting Engelsrud et al. (2021). As has been observed by researchers like Gauntlett (2021) and Hooper-Greenhill (2022), art education in the online space is successful when interactivity, creative freedom, and cultural background are incorporated in the design of the platform.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Review of Pedagogical Frameworks in Online Art Education |

|||

|

Focus Area |

Key Pedagogical Approach |

Technological Enablers |

Major Findings / Contributions |

|

Digital Studio Learning Farmani and Teather (2020). |

Constructivist and Experiential Learning |

Multimedia Tools, Online Studios |

Promotes learner autonomy and reflective art

practice through digital media. |

|

Rhetorical Pedagogy in Creative Media Johnson et al. (2019). |

Process-Oriented and Collaborative Models |

Interactive Writing Platforms, Digital Art Boards |

Encourages iterative critique and co-creation

between learners and mentors. |

|

Creativity in Online Learning Chiu et al. (2023). |

Experiential & Project-Based Learning |

Multimedia Authoring, Peer-to-Peer Platforms |

Effective when students produce and share creative

outputs within communities. |

|

Museum-Linked Online Art Learning Tommas et al. (2019). |

Contextual & Cultural Learning |

Virtual Museums, 3D Visualization |

Integrates cultural interpretation with artistic

skill development. |

|

LMS Performance in Art Courses Perfett et al. (2023). |

Blended Learning with Analytics |

Moodle, Canvas, LMS Analytics |

LMS effective for managing content but limited in artistic critique and affective feedback. |

On the management side of the problem, the literature also addresses the operational and strategic features of management of big online art sites. The research on learning management systems (LMS) including Moodle, Canvas, and Coursera states that scalability, resource distribution, and personalization are difficult (Khan et al., 2020). But the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is also increasingly perceived as a possible resolution. The engagement of the learners in the art education and automation of the feedback systems has been provided by the use of AI-based recommendation systems, adaptive content engines, and style-transfer algorithms. These technologies allow platforms to provide personalized learning experiences as well as give data informed decision-making information to administrators.

The other branch of study examines the economic and governance concepts that are the basis of creative education websites. The appearance of such platforms as Skillshare, Domestika, and Masterclass have contributed to the confusion of commercial and educational interests. The studies (e.g., Bakhshi and Throsby, 2020) have identified the impact that monetization policies (e.g., subscription levels, certification, and creator pay) have on content diversity and accessibility. In the meantime, platform governance is central to such issues as intellectual property rights, originality of artwork or culture. According to the literature, the key characteristics of the sustainable management of the activities are the provision of clear IP policies, inclusive content moderation, and the distribution of instructor compensation models equally among different parties. As indicated in Tables 1, past studies have contributed greatly to the knowledge of digital pedagogy and platform functioning, but not many models have comprehensively incorporated creative learning theories with data-driven management platform. This study aims to fill the gap by developing a platform management model as a whole based on pedagogical and technological innovation.

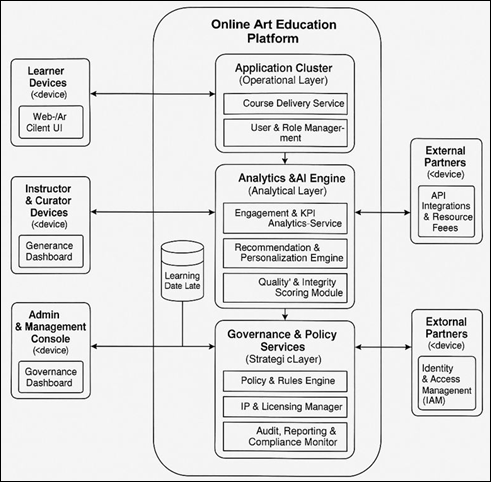

3. Platform Governance and Operational Model

The management of the online art education platforms needs an integrated governance system that would integrate pedagogy, technology, administration, and ethics in the distributed digital ecosystem. In contrast to traditional institutions where content is created and information transmitted centrally; these platforms include many stakeholders’ learners, instructors, administrators, curators, and external partners whose coordinated efforts provide content creation and quality assurance, monetization, and dissemination of knowledge. To guarantee the quality of instructions, governance mechanisms are based on human expertise and AI-driven analytics, where the pre-publication review, post-publication engagement analysis, and periodic expert revalidation allows guiding artistic authenticity through human-AI cooperation as shown in Figure 2 Sustainability in economics is ensured by flexible hybrid monetizing systems which include free access, subscriptions, premium masterclasses and transparent revenue-sharing, which are more and more backed by blockchain-based audits.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Governance and Operational Framework of Online Art Education Platform

The intellectual property governance ensures the protection of the rights of creators by Creative Commons license, provenance, and ethical management of AI-assisted art pieces and culturally sensitive content. To supplement such dimensions, strong data governance would make sure that privacy provisions, algorithmic transparency, and ethical controls would be adhered to avoid bias. Together these aspects are brought together in a governance architecture of stratum, operation and analytics that allows adaptive decision making, fair involvement and platform development in a balanced way of freedom of creation as well as institutional responsibility.

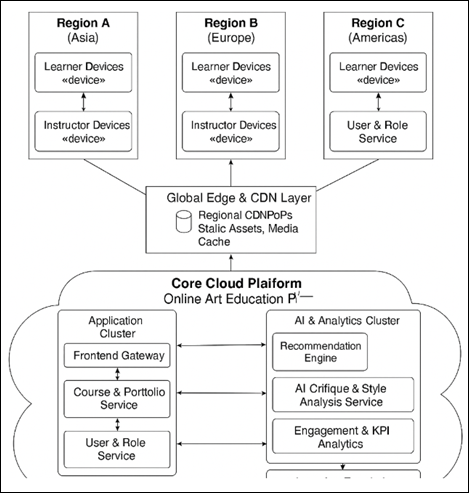

4. Proposed Backend Architecture and Cloud Resource Allocation

The success and scalability of online educational platform in art is largely determined by the technological infrastructure and the manner in which digital resources are planned, distributed and optimized with time. Art-oriented platforms are required to store high-resolution images, layered design files, 3D assets, time-based media, and AI-load to recommend, transfer styles, and critique unlike traditional e-learning systems that mainly process text and video. Such a combination leads to unique storage, compute, latency and fault tolerance requirements. A well designed infrastructure will result in learners enjoying low-latency content delivery and responsive creative tools and instructors and administrators of the service enjoying reliable analytics, governance and monetization services as shown in Figure 3 below. The platform core is a multi-tier backend architecture that is typically implemented on a hybrid or public cloud. The presentation layer is used to support web and mobile interfaces, which rely on the content delivery networks (CDNs) to store the static files such as video segments, reference images, and tutorials near the users. The application layer contains microservices with the primary role to user administration, course synchronization, assignment submission, portfolio rendering, and notification functionalities. To manage demand peaks on live workshops or global launches, auto-scaling makes use of dynamically scaling of compute resources on the basis of CPU, memory and I/O factors.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Deployment of AI-Assisted Creative Evaluation Services

The data tier is the compilation of the transactional databases with object storage and a learning data lake. Transactional database is used to store user profiles, enrollments, and financial documentation, whereas the object storage is used to store art files and versioned artifacts of a media artifact. Learning data lake consolidates the clickstream logs, interaction logs and the model output that are utilized in analytics and training AI. Resources planning should reflect the growth of storage due to portfolio and repetitive submissions; lifecycle policies can automatically move older or rarely-used assets to low-cost archival levels without access to it being restricted in any way to the types of assessments or accreditation. Decision-making Data Reasoninglimited by bandwidth and storage needs are met by instances of GPU-collaborative nodes or accelerators used to compute tasks with high computational demands as style transfer, image similarity search, and critique based on deep learning. These workloads can be batched or scheduled during off-peak period to optimize costs, and intermediary representation (e.g. feature embeddings) caching can be used in order to eliminate needless recalculation. Service meshes and API gateways deal with the communication between microservices and apply security policies and offer observability using measures and tracing.

5. Integration with Third-Party Tools (Payment, Analytics, AI Engines)

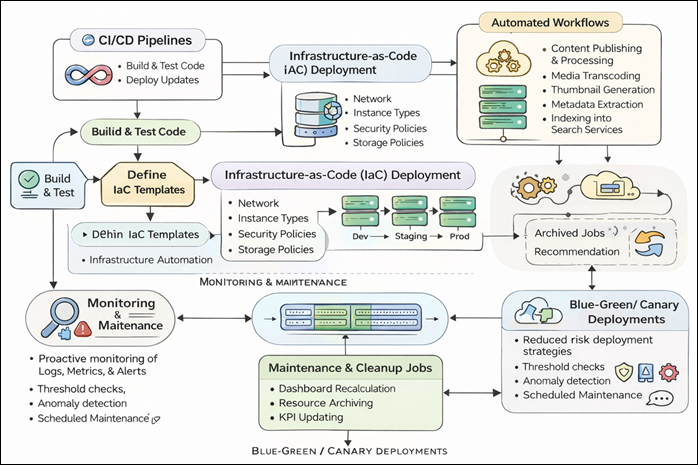

The technological infrastructure should allow the seamless integration of third-party services to enhance the capabilities of the platform without compromising on the governance and data security. Payment gateways enable international transactions, subscriptions, taxation and refunds and reveal a standardized API to invoice and report. These services can be related to the platform monetization module that harmonizes the revenues streams with the instructor royalty and institutional licensing agreements as it is depicted on Figure 4 below.

Figure 4

Figure 4 CI/CD-driven automation and maintenance architecture.

Business-intelligence and analytics platforms (e.g. embedded dashboards or cloud-native analytics services) process the streams of the data lake to calculate key performance indicators (KPIs) of the learner engagement, course effectiveness, and the churn. Role based access: this is where learners will view personalized progress views, instructors will see cohort level performance, and administrators will see aggregate metrics to aid in strategic planning. Extensive integration with third party AI engines gives the creative toolset a wider range of possibilities. Readymade vision models can offer standard style recognition, composition recognition or object recognition, whereas tailored models are trained on evaluation sets of works of art, drawings, or design tasks. Behind internal APIs these AI services are encapsulated such that input formats are standardized, rate limited and inferences events are logged so that they can be audited. In case of legal or ethical reasons, the platform may host models on its resource base in order to not transmit sensitive or copyrighted works to the third-party providers.

6. Workflow Automation and Maintenance

There is a need to have excessive workflow automatization in order to eliminate manual bottlenecks and minimize downtime in an online art education platform and operational excellence. The continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines continuously construct, check, and roll out the new features in a way that the changes in the creative tools or governance regulations spread uniformly across the services. The templates of infrastructure-as-code (IaC) are used to describe network setup, types of instances, security groups, and storage policies and create reproducible development, staging, and production environments.

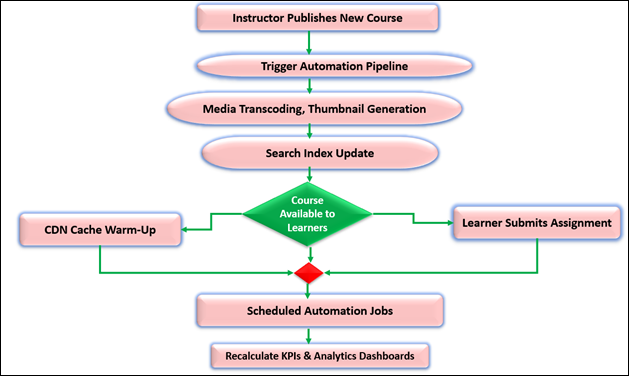

Content and assessment life cycles are also supported using automated workflows. As an example, pipelines can be activated in response to the publication of a new course by an instructor with the triggering of media transcoding jobs, the creation of thumbnails, the extraction of metadata, and indexing in search services. Background workers process assignments when submitted by learners to include virus scanning, format validation, pre-assessment by AI, and routing to instructors. Periodic jobs re-rank recommendations, store idle resources and refresh KPIs used in dashboards as represented in figure 5 above. Maintenance procedures are based on active monitoring of the system health in terms of logs, metrics and alerts. Anomaly-detection or threshold-based mechanisms help the administrators to know that there is a performance degradation, security anomalies, or misconfigured policies. Blue-green / canary deployment strategies minimize the occurrence of platform outages when performing significant updates, which is paramount in events with time constraints, e.g. live workshops, portfolio reviews, or certification tests. All of these automation and maintenance plans give a strong technological base, which can be used to bear the governance, pedagogical, and economic goals identified earlier.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Automated Content and Assessment Lifecycle Workflow

7. Performance Assessment and Risk Analysis

Quality assurance of any online art education platform will rely on performance evaluation and risk evaluation. In addition to the testing at a system level, platforms have to assess creative engagement, pedagogical outputs, and economic sustainability. The fact that it includes data visualization using performance graphs makes it easier to interpret and makes it possible to make data-based managerial decisions. As shown in the following (4-6) figures, critical dimensions learner engagement, financial sustainability, and system reliability are vital to show how quantitative analysis contributes to the addition of continuous improvement.

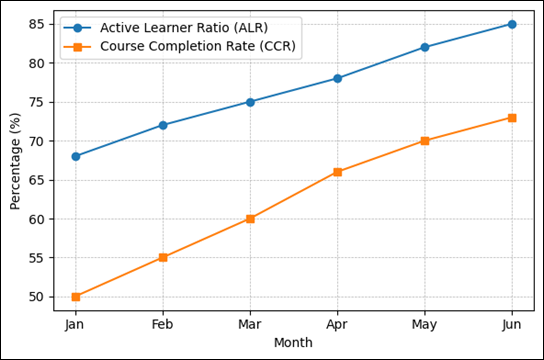

Figure 6, indicates that there is a strong positive correlation between Active Learner Ratio (ALR) and Course Completion Rate (CCR), which demonstrates the significance of the engagement-focused design. The higher the number of individuals engaged, the higher the completion rates are as 68% of those engaged translate to 50% completion rates and above 85% engagement translates to above 70% completion rates. The discussion indicates that interactive modules, peer critique system and creative assignments have a strong impact on increasing learner persistence. This data can be utilized by the administrators to adjust content pace, the duration of modules, and the frequency of feedbacks.

Figure 6

Figure 6 User Engagement vs Course Completion Rate

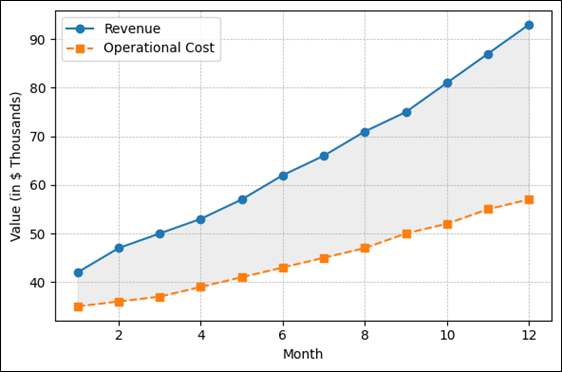

Figure 7, which brings out financial performance trend in twelve months, compares the revenue and operating costs. The expanding area is illustration of profit growth, wherein the revenues would exceed the costs by a margin of about 20 to 25 percent at the point of cycle termination. This implies that they have good monetization strategies, consistent subscription renewal, and effective deployment of resources. The trend validates that the hybrid revenue models (subscriptions and royalty systems) can increase economic strength and scalability, especially with the complements of automated resource planning and content pricing that vary dynamically.

Figure 7

Figure 7 Revenue Growth vs Operational Cost

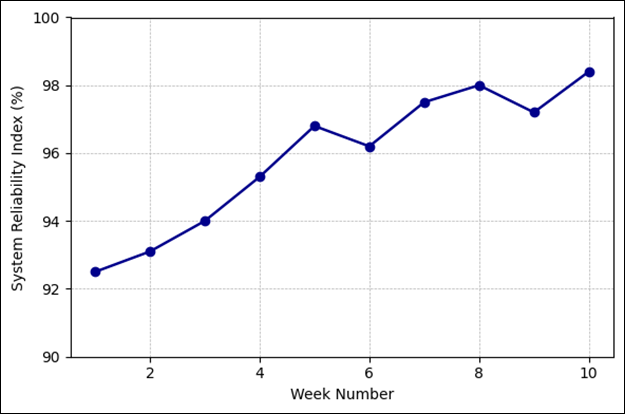

Figure 8 shows the System Reliability Index (SRI) using uptime, latency and error-rate measurements. It is apparent that automated monitoring, redundancy protocols, and regularly planned maintenance enhance reliability in the long-term as the trend of 92% to 98% over ten weeks is always on the increase. A decrease under the 95% threshold can be considered an incident diagnostics or performance scaling trigger. This quantitative monitoring system is in compliance with the ISO/IEC 27001 requirements on operational resiliency and assists in the long-term compliance with governance.

Figure 8

Figure 8 System Reliability Trend Over Time

8. Challenges and Limitations

Irrespective of the numerous benefits of online art education systems, there are a few challenges and limitations that remain and limit the pedagogical impact of the system, its widespread use of technologies, and its fairness in evaluation. It is important to acknowledge these limitations to put the proposed framework in its context and make future improvements.

1) Achieving the tactile, spatial and sensory aspects of traditional studio based learning has been one of the most basic challenges of online art education. The representation of art teaching is participatory and, in many cases, material contact, physical gesture, and instantaneous intervention of the teacher is involved.

2) Remote learning can cause learners to have different learning outcomes due to the lack of specific tools and materials or the absence of studio-based learning. In addition, it is challenging to digitize the real-time art process like the pressure of a brush, sculpting force, or the reaction of the material using a digital interface.

3) Peer critique and collective studio culture which is an important part of the development of art can also be watered down in the virtual world. Although this gap can be bridged partially in discussion boards and video critique, they tend to be less spontaneous and rich in experience.

4) Time-zone issues, and asynchronous contribution, make continued creative communication even more problematical. Consequently, teachers will have to put extra effort in creating pedagogical tools that will offer the right amount of flexibility and meaningful interaction, which is not necessarily scalable.

5) The effective implementation of online art education platform relies greatly on the availability of effective digital infrastructure and technical literacy of learners and their instructors. The use of advanced creative modules may even be discouraged by hardware limitations, including graphic tablet and GPUs unavailability or incompatible devices.

6) Institutional-level implementation of intricate cloud infrastructures, CI/CD pipelines, and AI services present financial and organizational issues. Smaller organizations or independent art groups might find it difficult to cope with the expenses of cloud computing, storage, and maintenance of the system. Also, instructors particularly those who are used to teaching in the studio may be resistant to technological change and this resistance may slacken the adoption. Technical support and training programs are thus needed but increase the overhead.

7) Although the AI-based assessment and feedback systems are more scalable and consistent, they have inalienable weaknesses when used to evaluate artistic works. The quality of art is usually contextual, subjective, and even culturally embedded, which is not easily measured using algorithmic measures only. The AI models that are trained with historical data have a high risk of being biased towards major styles or aesthetics, resulting in the discrimination of experimental, indigenous, or non-Western art forms.

This weakness requires human judgment to place creative value and provide equal consideration. Explainability is also a factor that should not be ignored; the learners will not necessarily trust and comprehend AI-generated feedback unless they are given clear explanations. Therefore, AI is to be considered as a supportive device instead of a judgmental one and as a part of a human-AI interactive system.

9. Conclusion and Future Work

The online art education platforms have been managed in a way that is a revolutionary amalgamation of technology, pedagogy, and artistic practice. This paper introduced a cohesive system of governance models, technological infrastructure, and strategic management that are aimed at maintaining and expanding digital art learning environments. Through the assessment of the system performance, user experience, and sustainability of operations, the study was able to demonstrate how data-driven decision-making and individualization of the system through AI can lead to the improvement of the quality of education and administration efficiency. The integration of the governance systems covering the intellectual property protection, ethical AI management, and cultural sensitivity will make sure that creativity and responsibility co-exist in the clear-cut operational framework. The results confirm that educational platforms of successful art learning are not entirely technological constructions but human-machine collaboration ecosystems. Adaptive feedback helps learners, high-end creative analytics instructors, and trustworthy performance measures help institutions, and lead to constant improvement. The suggested governance system with the help of hybrid AI assessment, content curative policies, and decentralized licensing systems creates an environment of fair inclusion and future confidence between interested parties. In prospect, future lab work might seek ways of integrating immersive technologies like virtual and augmented reality studios to recreate the feel of learning thus moving the gap between physical and digital forms of teaching. Studies on AI-based generative critique systems would be able to contribute to better creativity assessment, being both fair and understandable. Also, accreditation systems based on blockchains can provide verifiable credentials that allow global students to authenticate and share their accomplishments without risking any security violation.

Finally, the paper recommends a sustainable, inclusive and ethically monitored paradigm of online education in art whereby technology enhances creativeness, and the management practices that cultivate the artistic potential of the interconnected learning community that spans the earth. This innovation and art interconnection preconditions a new age of culturally sensitive, data-focused, and learner-cantered digital learning

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Brumfield Montero, J. (2021). Creating Student Relationships: From “Best Practices” to “Next

Practices” in a Virtual Classroom. Art Education, 74(1), 13–18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2021.1851888

Chiu,

M., Hwang, G., and Hsia, L. (2023). Promoting Students’ Artwork Appreciation

: An Experiential Learning-Based Virtual Reality Approach. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 54(2), 603–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13269

Cong, S. (2024). A Study of Teaching Strategies Optimized With the

Integration of Artificial Intelligence Technologies. Applied Mathematics and

Nonlinear Sciences, 9, Article 1195. https://doi.org/10.2478/amns.2023.2.00094

Critical Arts Education for Sustainable Societies (CARE/SS). (2024). CARE/SS Project.

Dai, Y.,

Liu, A., Qin, J., Guo, Y., Jong, M., Chai, C., and Lin, Z. (2022). Collaborative

Construction of Artificial Intelligence Curriculum in Primary Schools. Journal

of Engineering Education, 112(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20459

Ehtiyar, R., and Baser, G. (2019). University Education and Creativity: An Assessment From Students’ Perspective. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19, 1–20.

Engelsrud, G., Rugseth, G., and Nordtug, B. (2021). Taking Time for

New Ideas: Learning Qualitative Research Methods in Higher Sports Education.

Sport, Education and Society, 28(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1887123

Ezquerra,

Á., Agen, F., Rodríguez-Arteche, I., and Ezquerra-Romano, I. (2022).

Integrating Artificial Intelligence Into Research on Emotions and Behaviors in

Science Education. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology

Education, 18(12), Article 11927. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/11927

Farmani, Y., and Teather, R. J. (2020). Evaluating Discrete

Viewpoint Control to Reduce Cybersickness in Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality,

24(4), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-020-00441-1

Johnson, D., Damian, D., and Tzanetakis, G. (2019). Evaluating the

Effectiveness of Mixed Reality Music Instrument Learning With the Theremin.

Virtual Reality, 24(2), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-019-00406-2

Pavlou, V. (2022). Drawing From Pedagogy to Policy : Reimagining New

Possibilities for Online Art Learning for Generalist Elementary Teachers. Arts

Education Policy Review, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2022.2034526

Perfetti, L., Spettu, F., Achille, C., Fassi, F.,

Navillod, C., and Cerutti, C. (2023). A Multi-Sensor Approach to Survey

Complex Architectures Supported by Multi-Camera Photogrammetry. ISPRS Archives

of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences,

XLVIII-M-2–2023, 1209–1216. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLVIII-M-2-2023-1209-2023

Pyo, J. (2019). Latent Profile Analysis According to Intelligence–Creativity Mindsets of University Students : Differences in Learning Flow by Latent Group. Journal of the Korean Society for Créativité Education, 19, 37–53.

Quinn, R. D. (2011). E-Learning in Art Education: Collaborative

Meaning Making Through Digital Art Production. Art Education, 64(2), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2011.11519115

Sabol, F. R. (2022). Art Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic :

The Journey Across a Changing Landscape. Arts Education Policy Review, 123(3),

127–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2021.1931599

Somekh, B. (2007). Pedagogy and Learning With ICT : Researching the Art of Innovation. Routledge.

Tommasi, C., Fiorillo, F., Jiménez Fernández-Palacios, B., and Achille, C. (2019). Access and Web-Sharing of 3D Digital Documentation of Environmental and Architectural Heritage. In ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 42, 707–714. Copernicus GmbH. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-annals-IV-2-W6-707-2019

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.