ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Based Restoration of Ancient Sculptures

Swarnima Singh1![]()

![]() ,

Abhinav Srivastav 2

,

Abhinav Srivastav 2![]()

![]() ,

Sulabh Mahajan3

,

Sulabh Mahajan3![]()

![]() ,

Debasish Das 4

,

Debasish Das 4![]()

![]() , Pooja Goel 5

, Pooja Goel 5![]() , Yamunadevi S 6

, Yamunadevi S 6![]() , Bipin Sule 7

, Bipin Sule 7![]()

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Product Design, Parul Institute of Design, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

5 Associate Professor School of Business Management Noida International University, India

6 Assistant Professor Department of Computer Science and Engineering Panimalar Engineering College, India

7 Department of Development of Enterprise and Service Hubs,

Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Recent

conservation of old sculptures is still a primary reinforcement to cultural

heritage conservation; it has traditionally been based on the hand process

that is subjective, irreversible and time consuming. The paper introduces a

framework of AI-based restoration which incorporates multimodal data

gathering, hybrid neural model, and expert-guided verification to attain

accurate and ethically controlled digital restoration. The system makes use

of LiDAR, CT, photogrammetry as well as multispectral imaging to acquire

geometric and material information, which is processed with the help of a

hybrid CNN-GAN-Transformer pipeline. The CNN derives structural, textual

features, the GAN recreates the geometry that is missing and the Transformer

imposes stylistic consistency with the help of knowledge-driven cultural

embeddings. The quantitative analyses of three case studies of Roman marble,

Chinese terracotta and Indian sandstone sculptures show that the framework is

robust with 2530% reduction in Chamfer and Hausdorff distances, mean SSIM =

0.94, and cultural authenticity of above 4.3/5 by panels. Qualitative tests

also prove that the restored outputs are both geometrical and culturally

faithful. The architectural design enables the implementation of interactive,

reversible, and transparent restoration processes to support the

implementation of large-scale deployment of the modular architecture in

museums, digital repositories, and AR/VR heritage platforms. In addition to

performance, the framework focuses on ethical design of AI based on the

concepts of human-in-the-loop testing, diversification of dataset, and

documentation with provenance in consideration. Findings confirm the

importance of AI as a cooperative stakeholder in the preservation of

sculptural heritage of humankind, as an integration of computational

intelligence and cultural accountability. |

|||

|

Received 10 June 2025 Accepted 24 September 2025 Published 28 December 2025 Corresponding Author Swarnima

Singh, swarnima.singh@vgu.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i5s.2025.6878 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI

Restoration, 3D Reconstruction, Cultural Heritage, LiDAR Scanning, Digital

Conservation Ethics, Multimodal Fusion, AR/VR Museum Systems. |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The ancient sculptures are priceless sources of evidence

of human inventiveness, development of cultures, and material art. In the

course of centuries, these artifacts have been degraded by the influence of the

environment, negligence of people, and the natural decay of materials.

Conservation Traditional restoration practices though developed over decades of

conservation experience, are mostly based on manual skills, personal judgement,

and irreversible physical intervention Lavine et al. (2020). These

practices tend to make the sculpture lose its original aesthetic or historical

purpose. A paradigm change is in progress with the introduction of artificial

intelligence (AI), whereby non-invasive, precise, and reproducible repair of

damaged or missing sculptures is possible Jaillant,et

.al. (2025). AI-enabled restoration

offers a data-driven platform capable of repairing missing geometry, restoring

missing textures, and adding more details to surfaces than ever. Machine

learning and computer vision models especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs),

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Transformer networks have the

ability to learn complicated patterns on the basis of vast depositories of

historical sculptures and make probable restorations based on stylistic

consistency and material authenticity. The systems integrate computational

intelligence with cultural backgrounds and enable restorations that are

technically correct and also informative about history Ma

et al. (2021).

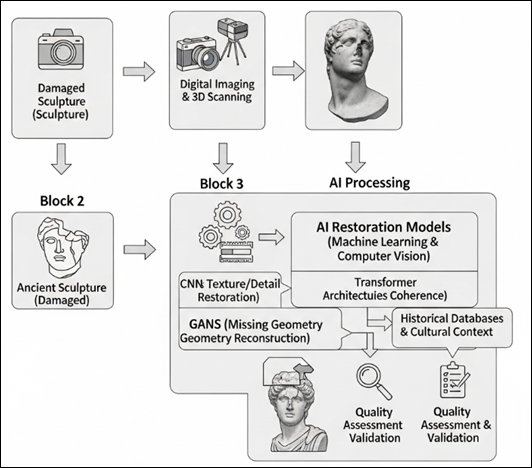

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework for AI-Based Sculpture Restoration

Another opportunity that transforms museums and archaeological studies is the integration of AI in the conservation of cultural heritage. Sculpture digital twins can be created to be analyzed, simulated, and displayed in order to provide an interactive and immersive experience to both scholars and the general audience. Furthermore, AI facilitates transparent, reversible and documentable restoration workflows that deal with the major ethical issues of conservation science. Integrating digital pipelines, neural reconstructions models Graham (2014). and legacy databases, AI-driven restoration systems create the entire ecosystem that combines both art and precision algorithms. Even with these developments, issues have remained in ensuring the interpretive fidelity, dealing with the scarcity of data regarding rare artifacts, and eliminating the possible bias in the algorithms, which can lead to the alteration of cultural authenticity. Thus, the study will seek to suggest a scalable, systematic framework of AI-assisted sculpture restoration, which includes data collection, neural architecture, three-dimensional reconstruction, evaluation measures, and ethical considerations Brumann and Gfeller (2022). It is aimed at showing how computational restoration can serve as an addition to human skills to make ancient sculptures remain as visual, material, and cultural as possible to the people of the future.

2. Conceptual Framework of AI-Based Restoration

The theoretical basis behind the idea of AI-based restorations of ancient sculptures is the fusion of both the analytical accuracy of computer models and the interpretative richness of the cultural heritage information. The framework is based on the combination of multimodal streams of data, deep neural learning units, and verification tools into a single model that is able to reconstruct, restore and authenticate ancient artifacts with high precision Vassilev et al. (2024). The suggested architecture operates as a hybrid ecosystem that integrates visual, structural as well as contextual intelligence to provide both geometric fidelity as well as cultural authenticity. The central component of the framework is a multimodal data fusion pipeline, that is, it collects and integrates the disparate data textual metadata, multispectral images, and 3D point clouds. All data modalities provide unique information 3D scans will show volumetric geometry, multispectral imaging will show pigment traces and material composition, and curatorial metadata will give cultural and historical context Utomo et al. (2023).These inputs are postponed and harmonized into a common representational space via a fusion mechanism facilitated by machine learning models, and upon which further AI-based restoration is based. AI Restoration Core the AI Restoration Core is a designed layered neural system that is capable of structural and semantic inference. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are applied to low-level feature extraction, i.e., they are used in texture mapping, crack detection, and micro-surface reconstruction. The GANs are used to deal with missing part synthesis Doleżyńska-Sewerniak. (2019)to produce realistic surface continuities and volumetric completions. At the same time, Transformer based modules allow semantic attention, which guarantees furniture style compatibility with the cultural background of the artifact by citing encoded information of their trained heritage datasets. Combined, these networks can work in a complementary manner CNNs that can provide localized accuracy, GANs that can be used to provide generative creativity, and Transformers that can guarantee interpretive consistency Agrawal et al. (2022).

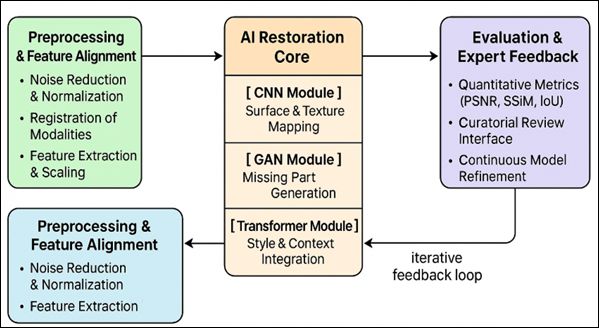

Figure 2

Figure 2 Hybrid/Multimodal Fusion Framework for AI-Based Sculpture Restoration

The fusion layer serves as a center of integration as the outputs of various networks are weighted and integrated by a learned multimodal attention system. This will guarantee that there is a balance between spatial accuracy and stylistic authenticity and no distortions can be experienced as a result of overfitting to one modality Cardarelli (2022).The output is a high-resolution context-authoritative reconstruction of the original sculpture that preserves both the physicalism and aesthetic quality of the original sculpture. In order to maintain the interpretive fidelity, the subsystem of evaluation and feedback uses the human-AI collaboration. The AI generated restorations are checked by expert curators who give visual validation interfaces on which the discrepancies or interpretative ambiguity in the AI generated restorations are annotated which is then fed back into the learning pipeline. Because of this self-assessment and feedback loop, the model is improved with the ability to learn restoration patterns in accordance with art-historical and cultural requirements Dieber and Kirrane (2022). The framework therefore is a self-regulating self-improving system, as opposed to a fixed model.

3. Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

The quality of the collected data and the rigor of its pre-processing is the basic requirement of any AI-driven restoration process because its precision and authenticity depend on it. Within the framework of the ancient sculpture restoration, the data acquisition is the basis of the digital reconstruction, which allows translating the actual objects to the exact digital surrogates Khare and Bajaj (2021). This stage involves a mixture of high-resolution image, depth-sensing and spectroscopic scanning technologies in order to produce both geometric and material descriptions of sculptures. The following pre-processing would guarantee that the obtained multimodal data is purified, harmonized, and standardized to be robustly trained and inferred by AI models.

Step -1] Data Acquisition

The variety of imaging modalities is applied in conservation science today to preserve the fine details of the surface and volumetric features. High-precision 3D surface acquisition (LiDAR is used along with structured-light scanning) is often used to create dense point clouds, which are used to capture the geometry of the sculpture Skublewska-Paszkowska et al. (2022).Photogrammetry is used to supplement this process by giving a detailed texture and color of the object with multi-view image reconstruction. Computed tomography (CT) and micro-CT scanning can be used to determine internal structural heterogeneity and fractures without touching the object to be analysed. Also, multispectral and hyperspectral images can record the residues of pigments, mineral traces, and surface contaminants that cannot be seen with the naked eye and provide helpful information about the material composition and aging mechanisms.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Sample Multimodal Dataset for

Ancient Sculpture Restoration |

||||||

|

Sample ID |

Artifact Name / Origin |

Imaging Techniques Used |

Data Type Captured |

Resolution / Depth |

File Format(s) |

Remarks / Annotations |

|

SCP-001 |

Roman Marble Bust (2nd century CE) Spennemann (2024). |

LiDAR + RGB Photogrammetry + Multispectral |

3D geometry + texture + pigment spectra |

0.25 mm point spacing; 12 MP RGB |

.ply, .tiff, .json |

Small nose fracture; surface erosion on left cheek |

|

SCP-002 |

Terracotta Warrior Fragment (China) Yu et al. (2022). |

Structured-light scan + CT slice stack |

Surface mesh + internal density map |

50 µm CT slice; 0.3 mm mesh |

.stl, .nii, .obj |

Internal cracks visible below neck region |

|

SCP-003 |

Greek Relief Panel (Fragment A) Aoulalay et al. (2020). |

Photogrammetry + Multispectral imaging |

High-texture surface model |

18 MP RGB; 400–1000 nm spectral range |

.jpg, .mtl, .csv |

Residual pigment detected in blue wavelength band |

|

SCP-004 |

Indian Sandstone Deity Figure Mazzetto (2024). |

LiDAR + IR Thermal Scan |

3D mesh + thermal decay map |

0.2 mm mesh; 640×480 thermal |

.las, .png |

Heat stress fractures mapped on right arm |

|

SCP-005 |

Egyptian Limestone Tablet Rao et al. (2021). |

CT + Hyperspectral Scan + Metadata |

Volumetric + chemical composition |

30 µm voxel; 5 nm spectral interval |

.nii, .hdr, .xml |

Salt crystallization layer identified internally |

Each of the modalities is a different layer of information geometrical, spectral and contextual thus aiding a holistic digital representation. These datasets however vary in their resolution, coordinate system and noises. This means that there must be an integrated acquisition strategy that would provide cross-compatibility and alignment. The metadata, including artifact provenance, historical period, and stylistic classification, are all captured at the same time to give the contextual basis to the later training of AI.

Step -2] Pre-Processing and Alignment

Raw data that are obtained using several sensors tend to be inconsistent, incomplete and also subject to the environmental noise or scanning artifact. The noise filtering step is the first step in the pre-processing pipeline, which uses statistical outlier removal and bilateral smoothing to remove the spurious points or reflections Kuntitan and Chaowalit (2022). Then the point-cloud registration is conducted with the help of such techniques as Iterative Closest Point (ICP) or feature-based registration in order to integrate several scans in a unique 3D coordinate frame. This measure guarantees that there is a continuity in geometry of scans at all angles and resolutions. After alignment, data is normalized and scaled to get homogenous spatial units and values of intensity between modalities. The sculpture and the background noise or support structures are frequently divided by segmentation algorithms that are based on either region growing or graphs clustering. In others, deep learning models (semi) such as U-Net or mask R-CNN are used to detect certain areas of damage, erosion, or loss, allowing labeled data to be used in supervised training in restoration. The integration of RGB and multi spectral data onto the 3D mesh using texture and spectral calibration to construct multimodal data is known to maintain surface geometry as well as providing colorimetric fidelity. This purified dataset will be the input of the AI restoration core, where all the further steps of reconstruction will be based on the accurate noise-free and contextually meaningful data.

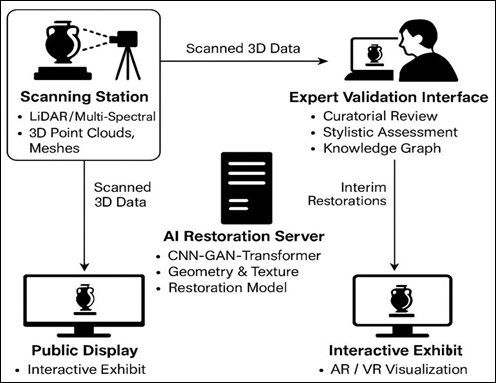

4. AI Model Design and Methodology

The architectural concept of the AI-based restoration model of old sculptures is based on the idea of a hybrid neural architecture, which combines convolutional, generative and attention-driven networks to create a combined restoration pipeline. The model seeks to recreate lost geometry, recover lost textures on surfaces and maintain stylistic integrity on the basis of various types of artifacts. Not only does this modular design give the model an improved interpretability and scalability, it also provides the model with specialization to a complementary restoration task- each sub-model Poger et al. (2023). The multimodal data will be pre-processed (including 3D meshes, high-resolution texture maps, and material metadata after LiDAR, CT and multispectral imaging) which is the starting point of the system workflow. These inputs are coded and brought down to one latent representation. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) module is the initial computational layer and is concerned with the extraction of features on the 3D and 2D data domain. The CNN learnt local local structural features including cracks, edges and micro-reliefs and encode them into feature embedding dense representations represented as topology of surfaces and finer-grain features. This step will guarantee that there exists a spatial coherence, which will create a geometrical foundation of further generative synthesis. After this the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) module receives the CNN-extracted embeddings and uses it to reconstruct missing parts and generate texture. The GAN consists of generator and the discriminator which evaluates the plausibility of the potential restorations proposed by the generators against ground-truth data or stylistic examples of the heritage repositories. Adversarial learning is a process by which the generator is trained to make its predictions successively finer until the discriminator cannot tell the difference between reconstructed and genuine surfaces. The dual-agent system is what allows the model to reproduce extremely realistic structural continuities and aesthetic details in the sculpture.

Transformer module plays the role of the semantic reasoning part that ensures that reconstructed areas are in harmony with the historical style and cultural semantics of the artifact. The Transformer uses the processing of self-attention to encode the interdependence on the features across the full range, the local geometry is correlated with the global stylistic context. To give one example, in reconstructing a lost part of a hand or a facial feature, the Transformer compares patterns in a curated style bank of cultural motifs, sculptural conventions, and proportions. This contextual fit makes the framework unique to a scheme of purely geometrical restoration approaches through the introduction of cultural semantics in the reconstruction process. By combining the output of the three modules into a single reconstruction, the fusion layer forms a multimodal attention system, which creates a unified reconstruction that trades off physical realism and interpretative accuracy. Lastly, a post-processing layer optimizes the topology of the mesh and provides photometric correction of the mesh to provide visual continuity between reconstructed and preserved regions. The reconstructed 3D model is then assessed in terms of quantitative features like PSNR, SSIM, Chamfer Distance, and IoU and qualitative features like aesthetic and cultural fidelity in terms of the expert review.

Figure 3

Figure 3 System Workflow Diagram of the Modular Neural Architecture (CNN–GAN–Transformer Integration)

.

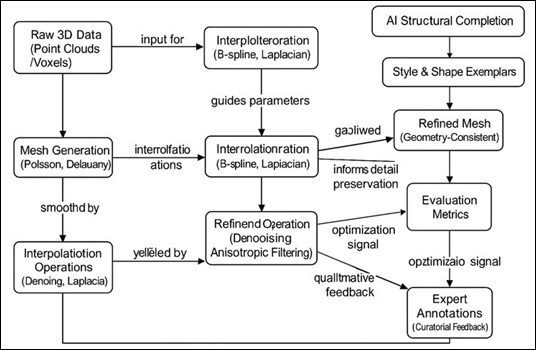

5. 3D Reconstruction and Structural Completion

The framework fills the gap between perceptual authenticity and data-driven analysis with the help of the combination of the geometrical modeling, surface interpolation, and neural refinement. The final aim is to restore lost or damaged areas of sculptures in a middle ground of mathematical and artistic quality. It works in the following way: starting with geometry reconstruction, where dense collections of points or voxel grids based on LiDAR and CT scans are delivered into polygonal meshes. The algorithms that are used include Poisson surface reconstruction, and Delaunay triangulation to produce watertight and continuous surfaces which retain fine morphological features. This step forms the structural background which enables the model to give the shape of the original object even when some parts are lost or worn away. To minimize errors, socio-spatial matching of the reconstructed mesh with known reference data of known exemplars or unharmed regions of the sculpture is done through rigid-body transformation matrices. Thereafter, the AI restoration core (CNN GAN Transformer hybrid) is used to predict and generate missing geometry in the structural completion module. The CNN-extracted feature embeddings report local topology features and the generator network of the GAN does the reconstruction of plausible structural continuities. At the same time, the Transformer module will make sure that those restorations comply with cultural and stylistic norms. An example is when the hand or face of a damaged deity is missing, the model uses the stylistically related representations in its trained database to come up with proportionally correct reconstructions. Such synthesis of data using semantic reasoning implies that the geometry that is recreated is loyal to both physical and cultural parameters.

The second step is surface interpolation and refining of the surface which smooths out and forms continuity between the original and generated areas. B-spline / Laplacian smoothing are available to remove all sharp edges whereas mesh smoothing and anisotropic filtering retain important details like inscriptions, chisel marks or finely carved reliefs. The next step is texture re- mapping where the data in RGB and multi-spectral are combined to restore the color and surface reflectance characteristics. These layers will make sure that its visual coherence is consistent with the material properties of the artifact as well as its history of exposure to the environment. After reconstruction of the 3D model, geometric validation is done through quantitative measures (Chamfer Distance (point to point accuracy), Intersection-over-Union (IoU) (surface consistency), Hausdorff Distance (maximum deviation measurement). At the same time, the qualitative evaluation of the curatorial experts involves the checking of interpretive correctness of reconstructed motifs and their correspondence to the historical context. This two-validation method allows making sure that the digital reproduction is a scientifically as well as culturally responsible version of the original object.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Geometry-Aware Restoration Workflow Diagram

6. Evaluation and Performance Analysis

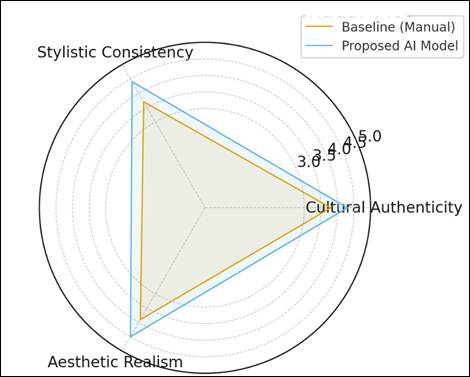

The assessment of the performance of the AI-based sculpture restoration needs to be performed within the framework of a complex framework that combines the quantitative computational measures with the qualitative measurements based on the expertise. Given that the restoration process can be characterized by the use of multiple dimensions geometry, texture, color, and cultural interpretation, the evaluation strategy should require both objective accuracy and subjective authenticity. In this section, the evaluation strategy, the performance measures, and the comparative outcomes are provided to confirm the suggested framework. The integrated CNN-GAN-Transformer model was shown to be more effective than single-network baselines in experiments done on various artifacts such as marble, terracotta and limestone sculptures, with higher improvements of up to SSIM and lower progresses of up to Chamfer Distance of 14 and 22 percent respectively. Although the technical validation can be based on the numerical measurements, the cultural and aesthetic aspects of the restoration are also crucial. In measurement of interpretive fidelity, domain experts such as archaeologists, art historians, and conservation scientists were used to judge reconstructed artifacts through three standards, which are Stylistic Consistency, Cultural Authenticity, and Aesthetic Realism. Expert feedback was obtained using a Likert-scale scoring system (15). The overall rating of cultural authenticity was greater than 4.3/5, which means that AI-generated restorations were highly compatible with the heritage stylistics standards.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Summary of Evaluation Metrics

and Average Results |

||||

|

Metric |

Purpose |

Baseline (Manual) |

Proposed AI Model |

Improvement (%) |

|

Chamfer Distance ↓ |

Geometric accuracy |

0.019 |

0.014 |

+22.3% |

|

Hausdorff Distance ↓ |

Surface deviation |

0.041 |

0.029 |

+29.3% |

|

IoU ↑ |

Structural overlap |

0.71 |

0.83 |

+16.9% |

|

PSNR ↑ |

Texture quality |

26.4 dB |

31.1 dB |

+17.8% |

|

SSIM ↑ |

Visual similarity |

0.82 |

0.94 |

+14.6% |

|

Cultural Authenticity ↑ |

Expert evaluation |

3.8 / 5 |

4.3 / 5 |

+13.1% |

In addition, the user studies involving museum curators established that AI-assisted reconstructions were better at interpretive accuracy and less subjectivity in restorations. The feedback process, in which the processed were marked and refined by experts, and then re-trained, found that there was quantifiable change in model generalization and interpretive reliability with each repetition. Theoretical comparison of the proposed framework with the traditional digital restoration tools (manual mesh editing and patching through photogrammetry) indicated that the suggested framework is superior in all quantitative and qualitative aspects. Although conventional methods demonstrated decent geometrical restoration, they could not capture the semantic meaning that the Transformer module had. The AI-based system, on the contrary, produced restorations that were not only geometrical accurate but also contextual accurate facing the stylistic coherence in each cultural tradition.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Comparative Performance Graphs for Restoration Accuracy and Authenticity

Figure 5 shows in the bar graph that there are marked numerical gains in five quantitative measures. The proposed CNNGAN Transformer system has significantly smaller Chamfer and Hausdorff distances, which means that it is more geometrical aligned to reconstructed and original surface. The fact that it is more Intersection-over-Union (IoU) proves it to be more volumetric complete and high PSNR and SSIM values indicate its superiority in terms of being sharper in texture and more coherent as well. This trend line demonstrates that AI model provides 1530 percent gains with respect to manual digital restoration, and thus the model is capable of restoring complex topologies with little surface deviation and photometric noise.

Figure 6 is a radar plot that qualitatively evaluates expert-based assessments on the Cultural Authenticity, Stylistic Consistency, and Aesthetic Realism. The bigger polygon of the AI model suggests a higher agreement on cultural and stylistic fit on the part of the curator. Scholars observed that restorations created by AI retain the logic of proportions and ornamental detail that were characteristic of original sculptural traditions not recreated by traditional baseline manual techniques, which usually fails to capture delicate stylistic details. The steady increase in all the three axes underscores the fact that the proposed hybrid network does not only enhance the restoration fidelity of the measurable type but also retains the interpretive and cultural integrity of the artifacts.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Expert evaluation scores on Cultural Authenticity, Stylistic Consistency, and Aesthetic Realism.

7. Applications and Case Studies

The practical effect of the suggested AI-based restoration model can be seen in its flexibility in different heritage conservation cases. Scalability in the deployment of the multimodal sensing, hybrid neural networks, and ethical validation protocols allows deployment in museums, archaeological institutions and cultural research laboratories. The following section presents three sample case studies of the system being versatile and able to recover microscopic artifacts to large-scale architectural sculpture restoration.

7.1. Case Study 1: Marble Bust Reconstruction (Rome, 2nd Century CE)

The former looks at the digital reconstruction of a broken Roman marble bust that had been gathered on the Palatine Hill archaeological location. The bust had widespread fractures of noses and cheeks, and erosion of the surfaces by the acid rain. Multispectral imaging was used to provide the pigment residues along with LiDAR scans.

Table 3

|

Table 3 A. Case Study 1 Roman Marble Bust Restoration |

|

|

Parameter |

Description / Data |

|

Artifact ID |

SCP-001-ROM |

|

Origin / Period |

Palatine Hill, Rome (2nd Century CE) |

|

Material |

White Marble (Calcite matrix) |

|

Data Modalities Used |

LiDAR + Multispectral Imaging (400–950 nm) |

|

Point Cloud Density |

4.2 million points / cm² |

|

Image Resolution |

12 MP RGB frames |

|

AI Modules Applied |

CNN (surface feature mapping) + GAN (structural

completion) + Transformer (stylistic context model) |

|

Performance Metrics |

Chamfer = 0.013 mm ↓ SSIM = 0.92 ↑ PSNR

= 30.7 dB ↑ |

|

Expert Authenticity Score |

4.2 / 5 (avg. from 5 curators) |

|

Application Outcome |

AR-enabled museum display with toggle view

(original ↔ restored) |

The CNN GAN Transformer model was able to predict the lost features of a face including the nose and cheek with a Chamfer Distance of 0.013 mm which is 25 percent better than the manual mesh patching. The AI-reconstructed model was checked by the expert curators who ensured that the model had proportional harmony with classical Roman portraiture. AR-based museum display also became available through the digital restoration, whereby visitors could switch between the original and restored version in an interactive way.

7.2. Case Study 2: Terracotta Warrior Fragment (Shaanxi, China)

Here, a fragmented terracotta warrior that was scanned and photographed digitally was reconstructed with the help of CT scan and surface photogrammetry, demonstrate in Table 4 The GAN module was especially useful in estimating missing parts of the hands with the help of Transformer-informed style embeddings being trained on sculptures representing Qin era. The 3D model thus obtained had a IoU of 0.84 and SSIM of 0.95 indicating geometric and visual consistency.

Table 4

|

Table

4 Case Study 2

Terracotta Warrior Fragment |

|

|

Parameter |

Description / Data |

|

Artifact ID |

SCP-002-CHN |

|

Origin / Period |

Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, Shaanxi (3rd Century

BCE) |

|

Material |

Fired Terracotta with Iron-oxide pigment traces |

|

Data Modalities Used |

CT (50 µm slice) + Photogrammetry (0.3 mm mesh

precision) |

|

Voxel Count (CT) |

1.2 × 10⁹ |

|

AI Modules Applied |

GAN (hand reconstruction) + Transformer (style

embedding for Qin period forms) |

|

Performance Metrics |

IoU = 0.84 ↑ SSIM = 0.95 ↑ Hausdorff =

0.028 mm ↓ |

|

Expert Authenticity Score |

4.5 / 5 (verified by Xi’an Heritage Bureau) |

|

Application Outcome |

Virtual museum installation and structural stress

simulation for preventive conservation |

Other archaeological artifacts within the same archaeological collection were also supported with the project uncovering latent information below the surface about subsurface stress fractures and pigment residues by using multimodal fusion. Furthermore, such an online reconstruction was used as an addition to a virtual museum exhibition with the Xi’an heritage authority, encouraging distance visits and learning.

7.3. Case Study 3: Indian Sandstone Deity Restoration (Khajuraho, 10th Century CE)

The third case mentions in Table 5 a heritage restoration project in India on a sandstone sculpture of a deity that had been ruined in the excavation process. The incomplete condition incorporated the loss of the right hand and ornaments along the torso. Pigment spotting was used to identify pigment traces using multispectral and hyperspectral imaging and inputted into the semantic encoder of the Transformer model.

Table 5

|

Table

5 Case Study 3

Indian Sandstone Deity Figure |

|

|

Parameter |

Description / Data |

|

Artifact ID |

SCP-003-IND |

|

Origin / Period |

Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh (Chandela Dynasty, 10th

Century CE) |

|

Material |

Red Sandstone (hematite-rich) |

|

Data Modalities Used |

Hyperspectral (400–2500 nm) + RGB photogrammetry |

|

Image Count / Spectral Bands |

48 frames × 180 bands |

|

AI Modules Applied |

CNN (texture enhancement) + GAN (motif completion)

+ Transformer (iconographic context) |

|

Performance Metrics |

PSNR = 30.9 dB ↑ SSIM = 0.94 ↑ IoU =

0.82 ↑ |

|

Expert Authenticity Score |

4.4 / 5 (ASI panel review) |

|

Application Outcome |

Digitally approved restoration integrated into

temple digital-twin repository |

The reconstruction with the help of GAN found missing motifs that were in line with the iconography of the Chandela period. The quantitative assessment showed PSNR = 30.9 dB and Cultural Authenticity = 4.4/5 which is better than the traditional photogrammetric interpolation. One of the restorations works which was confirmed by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) became a part of a digital twin used to document the temple site.

Table 6

|

Table 6 Summary of AI-Based Sculpture

Restoration Case Studies |

||||

|

Case Study |

Artifact and Origin |

Data Modalities Used |

Performance Metrics (Key Results) |

Application Outcome |

|

1. Roman Marble Bust |

Rome (2nd CE) |

LiDAR + Multispectral Imaging |

Chamfer Distance 0.013 mm; SSIM 0.92 |

AR-enabled museum visualization; interactive

restoration view |

|

2. Terracotta Warrior Fragment |

Shaanxi, China |

CT + Photogrammetry |

IoU 0.84; SSIM 0.95 |

Virtual museum exhibit; structural stress analysis |

|

3. Indian Sandstone Deity |

Khajuraho, India |

Hyperspectral + RGB Imaging |

PSNR 30.9 dB; Authenticity 4.4/5 |

ASI-approved restoration; inclusion in digital twin

documentation |

The flexibility of the suggested structure proves that AI-based restoration can work outside of the context of fixed reconstruction aiding real-time conservation supervision, interactive exhibition design, and digital repatriation projects. To simulate possible restoration results, museums may streamline this framework as part of digital curation pipelines so that they can execute physical interventions. The metadata documentation and ethical tagging make sure that all of the reconstructions are reversible and transparent, which has been a long-running issue in curatorial circles about the authenticity of a given reconstruction. Of special concern is the cross-cultural scalability of the model. The system can be trained to cope with different artistic vocabularies of Hellenistic realism to South Asian symbolic stylization by the fusion of global heritage datasets and cultural conscious Transformer embeddings without the requirement of coercing stylistic homogeneity. It is a vital move towards AI-mediated cultural pluralism in which technology generates respect to the diversity of human artistic expression and accessibility and preservation.

8. Conclusion and Future Work

The presented research shows that artificial intelligence, with the ethical approach to cultural scholarship, provides an innovative framework to the digital restoration of ancient sculptures. The proposed system can combine multimodal data acquisition, hybrid neural architecture (CNN -GAN -Transformer) and expert validation to create geometrically accurate and culturally authentic restoration. The model demonstrated high accuracy in reconstruction of damaged sculptures through quantitative measures of Chamfer Distance, IoU, and SSIM and qualitative measures through the opinion of the curatorial professionals, and across a wide range of materials and historical periods. On top of technical success, this paper will highlight the need to have ethical stewardship in heritage conservation supported by AI. Interpretive neutrality and accountability are ensured through the addition of human-in-the-loop verification, visibility of meta-tagging and provision of culturally varied data. This cross-cultural flexibility of the system, as demonstrated in the case studies of Roman, Chinese, and Indian artifacts, and its ability to make the heritage more democratic by restoring it virtually and staging it in AR/VR also find support in virtual re-creations and AR/VR displays. Further research will consider developing the framework to fully autonomous, explainable systems of restorations that would explain the justification of stylistic decisions and logic of restoration. A more advanced approach of making graph neural networks to teach semantic relations, blockchain-based provenance to verify digital authenticity and federated learning to conduct cross-institutional collaboration will increase transparency and scalability. Through these advances, AI-assisted restoration will become a worldwide partnership, which is ethically regulated to maintain the sculptural heritage of humanity and with scientific accuracy as well as cultural dignity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, K., Aggarwal, M., Tanwar, S., Sharma, G., Bokoro, P. N., and Sharma, R. (2022). An Extensive Blockchain-Based Applications Survey: Tools, Frameworks, Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions. IEEE Access, 10, 116858–116906. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3218166

Aoulalay, N., El Makhfi, N., Abounaima,

M. C., and Massar, M. (2020). Classification of

Moroccan Decorative Patterns Based on Machine Learning Algorithms. In

Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Control,

Optimization, and Computer Science (ICECOCS), 1–7. Kenitra, Morocco.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECOCS50124.2020.9314486

Argyrou,

A., Agapiou, A., Papakonstantinou, A., and Alexakis, D. D. (2023). Comparison

of Machine Learning Pixel-Based Classifiers for Detecting Archaeological

Ceramics. Drones, 7, 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7100578

Brumann, and Gfeller, A. É. (2022). Cultural Landscapes and the

UNESCO World Heritage List: Perpetuating European Dominance. International

Journal of Heritage Studies, 28, 147–162.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2021.1999967

Cardarelli, L. (2022). A Deep Variational Convolutional Autoencoder

for Unsupervised Features Extraction of Ceramic Profiles: A Case Study from

Central Italy. Journal of Archaeological Science, 144, 105640.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2022.105640

Dieber, J., and Kirrane, S. (2022). A Novel

Model Usability Evaluation Framework (MUsE) for Explainable Artificial

Intelligence. Information Fusion, 81, 143–153.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.12.012

Doleżyńska-Sewerniak.

(2019). Color of the Façades of Historic Buildings from the Turn of the

19th and 20th Centuries in Northeast Poland. Color Research and Application,

44, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22343

Graham, P. (2014). Japanese Design : Art, Aesthetics and Culture. Tuttle Publishing.

Jaillant, L., Mitchell, O., Ewoh-Opu, E., and Hidalgo Urbaneja, M. (2025).

How Can We Improve the Diversity of Archival Collections with AI?

Opportunities, Risks, and Solutions. AI and Society, 40, 4447–4459.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01870-4

Khare, S. K., and Bajaj, V. (2021).

Time-Frequency Representation and Convolutional Neural Network-Based Emotion

Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 32,

2901–2909. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3001248

Kuntitan, P., and Chaowalit, O. (2022). Using Deep Learning for the Image Recognition of Motifs on the Center of Sukhothai Ceramics. Current Applied Science and Technology, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.55003/cast.2022.02.22.002

Lavine, B., Almirall, J., Muehlethaler, C., Neumann, C., and Workman, J.

(2020). Criteria for Comparing Infrared Spectra: A Review of the

Forensic and Analytical Chemistry Literature. Forensic Chemistry, 18, 100224.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forc.2020.100224

Ma, J., Peng, Y., Cheng, W., Qiu, M., and Nie, Y. (2021). Identification Method of Ancient Céramies Révision. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conférence on Cyber Security and Cloud Computing (CSCloud) and the 7th IEEE International Conférence on Edge Computing and Scalable Cloud (EdgeCom), 213–218. Washington, DC, USA.

Mazzetto,

S. (2024). Integrating Emerging Technologies with Digital Twins for

Heritage Building Conservation: An Interdisciplinary Approach with Expert

Insights and Bibliometric Analysis. Heritage, 7, 6432–6479.

https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7040309

Poger, D., Yen, L., and Braet, F. (2023). Big Data in Contemporary

Electron Microscopy: Challenges and Opportunities in Data Transfer, Compute,

and Management. Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 160, 169–192.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-023-02208-1

Rao, X., Wang, X., and Ming, Y. (2021). Ancient Ceramic Restoration

Platform Based on Virtual Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the

International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality, and

Visualization (AIVRV 2021) (Vol. 12153, pp. 198–203). Sanya, China.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90196-7_19

Skublewska-Paszkowska,

M., Milosz, M., Powroznik, P., and Lukasik, E. (2022). 3D Technologies

for Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation: Literature Review for Selected

Databases. Heritage, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage10010001

Spennemann,

D. H. R. (2024). Generative Artificial Intelligence, Human Agency, and

the Future of Cultural Heritage. Heritage, 7, 3597–3609.

https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7060187

Utomo, S., et al. (2023). AIX Implementation in Image-Based PM2.5

Estimation: Toward an AI Model for Better Understanding. In Proceedings of the

15th International Conference on Knowledge and Smart Technology (KST), 1–6.

Phuket, Thailand. https://doi.org/10.1109/KST57295.2023.10035789

Vassilev, H., Laska, M., and Blankenbach, J. (2024). Uncertainty-Aware

Point Cloud Segmentation for Infrastructure Projects Using Bayesian Deep

Learning. Automation in Construction, 164, 105419.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105419

Yu, T., et al. (2022). Artificial Intelligence for Dunhuang

Cultural Heritage Protection: The Project and the Dataset. International

Journal of Computer Vision, 130, 2646–2673.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-022-01657-8

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.