ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Human–Computer Interaction Models in Art Pedagogy

Abhiraj Malhotra 1![]()

![]() ,

Divya Sharma 2

,

Divya Sharma 2![]() , Kishore Kuppuswamy 3

, Kishore Kuppuswamy 3![]()

![]() ,

Akhilesh Kumar Khan 4

,

Akhilesh Kumar Khan 4![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Bhagyalaxmi Behera 5

,

Dr. Bhagyalaxmi Behera 5![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Kamal Sutaria 6

,

Dr. Kamal Sutaria 6![]()

![]() ,

Leena Deshpande 7

,

Leena Deshpande 7![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Sciences, Noida International University, India

3 Professor

of Practice, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s

Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

4 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

5 Associate

Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

6 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Faculty of

Engineering and Technology, Parul Institute of Engineering and Technology,

Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

7 Department

of Computer Engineering - Software Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Incorporation

of the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) models in the art pedagogy has

changed the way learners interact with the digital

creativity with the focus on the interactive, experiential and multimodal

approaches to the artistic education. This paper

discusses the role of cognitive and behavioral modeling in the HCI models in

improving the digital art learning conditions using adaptive and

feedback-based systems. The study is based on the theories of constructivist

and experiential learning, investigating how creativity and self-expression

can be supported by the direct manipulation interface, immersive platform,

and generative AI tools. The methodology is a combination of both qualitative

and quantitative data gathered through observations in the classroom,

surveys, and interviews with the art educator and students in the use of

digital art software and interactive learning systems. The measurement of

interaction patterns, engagement rates, and learning outcomes are measured by

analytical methods in order to determine the

pedagogic importance of interface design and multimodal feedback. The results

show that properly developed HCI systems have a positive influence on

engagement, experimentation, and increase the confidence of students in their

creativity. In addition, multimodal interfaces with visual, auditory, and

touch-hearing aspects help to build deeper cognitive associations, which lead

to better conceptual knowledge and aesthetic decision-making. The discussion

indicates the necessity of adaptive digital tools, inclusive, and contextual,

which are compatible with the artistic cognition. This study is part of the

new body of art-oriented HCI, which promotes an educational model in which

interactivity is the medium of creativity, as well as an agent of learning,

and the future of online art education. |

|||

|

Received 03 May 2025 Accepted 06 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Abhiraj

Malhotra, abhiraj.malhotra.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6871 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Human–Computer Interaction, Digital Art Education,

Creative Pedagogy, Multimodal Interfaces, Cognitive Learning Models,

Interactive Design |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Incorporation of the Human -computer Interaction (HCI) concepts in art education has been a way of redefining the essence of artistic study and creative exploration in the digital era. With education gradually shifting to the hybrid and technology-enriched context, the limits between artistic expression and computational design have been blurred, providing space to interactive and immersive learning. The pedagogy of art which has traditionally been based on the sensory observation, emotional involvement, and manual practice is now spread into the digital sphere where students get to learn by using interfaces, algorithms, and multimodal interactions. This change prompts educators and researchers to re-evaluate the role of digital tools in defining the creative process and how HCI models can improve the creative cognition, collaboration and expression of academic and studio based learning settings. As an interdisciplinary study, Human-Computer Interaction is presented with the study of the design and evaluation of systems which are used to create meaningful interactions between humans and digital environments. In the field of art education, this system goes beyond the functionality to include aesthetic experience, emotional involvement, and creative decision-making Carthy et al. (2021). The history of HCI as a development of command-based computing to multimodal, adaptive and intelligent interface interfaces is similar to what was happening to art pedagogy as a transformation of a passive teaching method to a participatory and experiential approach of learning. Highlighting the principles of HCI by giving it responsiveness, feedback, and personalization, these digital tools enable the learners to engage dynamically with digital tools and allow a more intuitive and reflective engagement with the creative process. With the emergence of digital art software, immersive media and generative AI tools, the pedagogical opportunities of art education have increased Toner et al. (2023).

Students can now come up with manipulation of complex visual structures, experimentation of color theory in simulation, or simulation of 3D surroundings that simulate physical studio situations. Not only do these tools imitate the traditional media, but also present new forms of expression, which did not exist before and are guided by the concept of HCI design. The visual, modular, and generative power of the computational models of visual art stimulate an iterative, enquiry-driven process of learning, which is consistent with the constructivist and constructive learning theories Lin et al. (2024). Such settings make learners participants in the construction of knowledge as well as creative associates and thought extensions through digital tools. In addition, pedagogical models that are guided by HCI consider inclusivity and access. With digital interfaces, art education will be able to reach larger audiences because they can be modified to various learning styles, physical abilities, and cognitive preferences. Multimodal interactions (visual, auditory, and tactile) are also incorporated and this allows increased sensory involvement, which is essential in the formation of aesthetic consciousness and artistic instinct Zhang and Shen (2024). Such inclusivity does not only democratize the learning of art, but also promotes collaboration and peer to peer creativity in the virtual or hybrid classroom.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Principles of Human–Computer Interaction

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) is based on the observation and design of interfaces which ensure effective, efficient, and even satisfying communication between humans and computers. The main principles of usability, accessibility, feedback, consistency, and affordance are the basis of the interactive system design in digital art education. Usability is a factor that guarantees that the art tools are in line with the creative intention of the learners; that the technical barriers are reduced to the minimum possible, and that the expressive possibilities are maximized. The feedback gives instant visual or physical feedback which reinforces the actions of the user which enables learners to perfect their artistic processes on the fly Wang (2024). The presence of consistency between digital interfaces makes exploration intuitive and has a lower cognitive load, whereas the communication of interface features (e.g., affordance) defines the visual indication of interface components, helping learners explore the interface naturally. Applying HCI principles to the domain of art pedagogy, the concept of efficiency in interaction is replaced with an emotional appeal and aesthetic experience. These principles are reflected in interactive artistic devices like software of digital painting, generative art, and virtual sculpting models Gisby et al. (2023). The objective is to seek ways of establishing conditions in which learners will be able to utilize technology as an organizational companion instead of a robotized restraint.

2.2. Cognitive and Behavioral Models in User Interaction

HCI cognitive and behavioral models offer theoretical constructions to comprehend the way users perceive, learn and behave in interactive systems. Cognitive frameworks like the Seven Stages of Action by Norman, or the Model Human Processor by Card, Moran, and Newell, explain the way users process feedbacks and strategize as well as physically map the system operation. The models play a vital role in the creation of digital art interfaces that conform to mental images of creative activities among the users Gates (2024). As an example, in cases where learners employ digital sketching or 3D modeling tools, the system response should be able to supplement their perceptual and motor abilities so that creativity flow is sustained and cognitive dissonance diminished. On the other hand, behavioral models focus on observable interaction patterns, user motivation and reinforcement mechanisms. These frameworks are based on the behaviorist psychology and emphasize the role of feedback loops, rewards and responses to adapting to user engagement Abdulai et al. (2023). These models assist in organizing interactive lessons, gamified education space and feedback based assessment systems that facilitate motivation and learning in cycles in digital art pedagogy. Table 1 provides a summary of reviewed studies, where it is possible to identify themes, contributions, methods, and research gaps. By incorporating cognitive and behavioral models, educators are able to create adaptive interfaces which do not only reflect the thought process of humans but also promote a constructive experimentation and persistence.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Review |

|||

|

Focus |

Benefits |

Limitations |

Future Trends |

|

Comparative analysis of

interactive art works and HCI research Duranti et al. (2024) |

Bridges artistic creativity

and structured HCI evaluation; provides taxonomies for interface design in

art contexts |

Recognizes that not all

interactive art uses explicit HCI methodology; variability in evaluation

approaches |

Advocate for more structured

evaluation, cross-pollination between art and HCI; more inclusive, diverse

interactive art research |

|

HCI education via creation

of interactive art Petrelli and Roberts (2023) |

Promotes creative, hands-on

learning; fosters understanding of user-centered

design via artistic experimentation; enhances motivation |

Requires resources and

open-ended tasks; may be challenging for students unfamiliar with art

practices |

Suggests integrating

interactive art into HCI curricula for broader skill development; expand to

more diverse student backgrounds |

|

Sketching as pedagogical

tool in HCI/UX and art-design education Chang et al. (2023) |

Enhances ideation,

conceptual thinking, design fluency; supports peer-to-peer learning and

collaboration; bridges art and design thinking with technical curricula |

Sketching remains

under-utilized in computational curricula; risk of marginalization when

framed only as “preliminary design” |

Expand use of sketching

beyond early design phases; integrate with digital tools, hybrid pedagogy,

remote learning environments |

|

Participatory video platform

for interactive art Falk and Dierking (Eds.). (2018) |

Improves user engagement,

reduces operation time, enhances interactive communication and participation

in art |

Current experiments are

limited; full-scale online deployment and long-term evaluation pending |

Future work: broader user

studies, social features, scalability to multiple users / collaborative

creation |

|

Emerging HCI in immersive /

metaverse environments applied to creative interaction / design |

Opens new modalities for art

creation, collaboration, spatial/3D expression, and immersive pedagogy;

expands possible interaction dimensions |

Concerns about access,

equity, hardware costs, digital divide, and cultural context sensitivity |

Future trend: inclusive,

affordable immersive systems; cross-platform art education; user-centered and culturally aware metaverse art tools |

|

Use of generative AI (GenAI)

by students in HCI education — implications for creativity & design Bartelds et al. (2020) |

Accelerates ideation cycles,

stimulates creativity and experimentation; lowers entry barrier for complex

design tasks |

Risk of over-reliance on AI,

reduced depth in conceptual learning |

Suggest curriculum design to

integrate GenAI meaningfully: combine AI-based generation with critical

reflection, manual refinement, and conceptual grounding |

3. HCI Models in Artistic Contexts

3.1. Interaction paradigms: direct manipulation, immersive systems, and generative interfaces

Interaction paradigms determine the way users approach the digital systems, and it defines their creative process and artistic workflow. Three paradigms of digital art pedagogy—direct manipulation, immersive systems and generative interfaces allow different interaction modalities of a creative process. Direct manipulation Interfaces like drawing tablets (or digital sculpting tools) enable learners to provide intuitive control over digital objects by gesture, stylus or touch input Angeli et al. (2021). This immediacy circumvents the human will and the computer reaction, giving immediate feedback and encouraging continuity in the making of art. Immersive systems are virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), which project the conventional workstation into the three-dimensional and multisensory space. These systems put the learners into interactive spatial and experiential learning environment in which they are able to study the scale, perspective, and composition in a dynamic manner. The amount of immersion can be used to enhance creativity through embodiment that is the feeling of being inside the artwork and makes the learning experience highly immersive Berger and Kansteiner (2021). Generative interfaces bring in the elements of artificial intelligence and algorithmic creativity in the learning process.

3.2. Adaptive Learning Systems and Feedback Mechanisms in Art Software

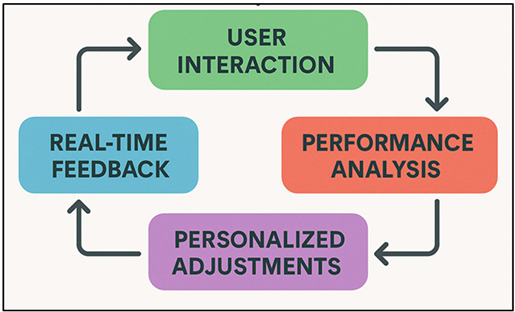

Art education Adaptive learning systems Adaptive learning systems in art education make use of Human-computer Interaction principles to customize creative instruction and encourage exploration at a self-paced pace. These systems are responsive systems that adapt dynamically to the skills of the user, preferences, and artistic behaviours to change the complexity and feedback accordingly. Adaptive art platforms can determine the learning patterns by analyzing the data of user interaction, like the pattern of brushstrokes or design options, and provide personalized instructions or challenges that reflect certain progress Pescarin et al. (2023). The feedback systems are critical towards ensuring engagement and cognitive development. Feedback in HCI based art software may be visual (posing emphasis on compositional balance), auditory (suggesting tonal / rhythmic emphasis), or textual (indicating a design change). Learning is supported by feedback loops and the user can always examine his/her decisions in real-time. Figure 1 demonstrates adaptive feedback loops that allow improving personalized learning in digital art systems. Digital painting systems can be used as an example, and they can simulate the behavior of materials or the shift in lighting and the students can therefore learn about the depth in space and the harmony of colors through the experience.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Adaptive Feedback Loop Architecture in Digital Art Learning Systems

The use of machine learning also increases flexibility by forecasting the intentions of creativity or suggesting changes in style. These smart systems foster the process of experimentation, reflection, and refinement, which are the main components of building artistic maturity. Adaptive feedback is also used in education, in which systems visualise progress metrics or creative milestones, in order to support peer collaboration.

3.3. Role of Multimodal Interfaces

Multimodal interfaces add the multimedia experience to Human-Computer Interaction by incorporating several of the sensory modalities: visual, auditory, and tactile, and making the artistic learning and expression a holistic experience. Digital art education is dominated by visual senses that draw intuitive feedback in the form of color, composition, and space. The interactive visual displays, overlayed canvases and real time 3D representations enable the learner to experience the immediate consequences of their actions to promote spatial learning and aesthetic decision-making. Auditory modalities are complementary to visual inputs that provide rhythm, emotional tone and temporal feedback to creative tasks Lazem et al. (2022). Sound cues may be used in the media arts courses or interactive design courses to direct actions, give signals to states of a system, or cause affective responses to inform artistic choices. Citing an example, sound making instruments are used to train students on the interactions between auditory patterns and visual movement, which encourages students to be cross-modal creators. The physical aspect of digital art interaction is a tactile feedback, typically provided by a haptic device, touchscreen or through pressure-retaliating tools. This feeling of touch makes virtual creation material once again, filling the sensory divide between physical and digital media. Students learning with haptic-based sculpting equipment, such as the one mentioned, feel the pressure and feel of a real sculpt of clay, making it look and feel more realistic and immersive.

4. Integration of HCI in Art Pedagogy

4.1. Application in digital art studios and classrooms

Human-Computer interaction (HCI) application within digital art studios and classrooms transforms the teaching, learning and assessment of the artistic skills. Interactive technologies and elements of contemporary art education environments include digital tablet devices, augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and AI-assisted creative tools, which can be applied to the learning process. Such systems will turn the classic studios into animated technology-enhanced environments in which learners can engage with virtual canvases, generative systems, and sensory feedback systems. It is focused more on the participation than passivity and encourages critical thinking, experimentation, and personal expressions. HCI-based digital studios are collaborative and self-directed learning environments. Learners have the ability to visualize more complicated works of art, play with 3D objects or calculate surroundings to comprehend light, texture and perspective. Design environments based on clouds can be used to facilitate real-time collaborative creation, peer review and critique, taking a studio practice out of the physical space. Teachers gain the ability to make changes and provide feedback through the insights that analytics gives about how learners are performing.

4.2. Interface Design for Creative Expression and Exploration

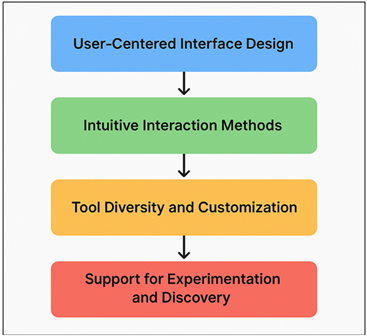

Successful Human-Computer Interaction in art pedagogy is based on effective interface design because it directly influences the interaction of learners with the creative tools. An interface should clearly be organized to ensure that the functionality, the beauty, and cognitive ease are balanced which allows the user to explore the interface with natural ease without being overwhelmed by the interface. In the art pedagogy discipline, interface design is not simply technical, but is also pedagogical and affects the way students see artistic possibilities and how they render imagination into a form.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Interface Architecture for Creative Expression and Exploration

The main design concepts like affordance, feedback, and adaptability make sure that the users can manipulate the element of the artwork with their hands in an intuitive manner. Figure 2 displays interface architecture in favor of creative expression, exploration and responsive artistic interaction. Immersive and minimalist designs keep the learner in the flow of creativity, and a minimal number of cognitive friction points, such as tooltips in the context, gesture support, and dynamic menus. Interfaces are also considered to be creative scaffolds, where students are directed through complicated artistic processes, like harmonizing colors, correcting perspective, or creating patterns, but where improvisation is still possible. Addition of aesthetic consistency and emotion appeals into interface design intensify creative motivation more.

4.3. Case Studies of HCI-Based Art Learning Platforms

A number of novel platforms demonstrate the nature of how the principles of HCI improve learning of art by providing interactivity, flexibility, and sensory stimulation. A case in point is Autodesk SketchBook, which combines direct managing, stacked procedures, and customizable brushes to replicate the companion in the studio, notwithstanding the digital accuracy. It has an interactive feedback system where the learners can adjust their methods of drawing intuitively. Equally, both Tilt Brush and Adobe Medium use immersive VR to enable the students to paint or sculpt in 3D space, combining spatial awareness with embodied creativity. Such applications are a clear illustration of the way in which understanding of form and composition is further enhanced. Co-creating algorithms in generative and AI-based applications like RunwayML, Artbreeder, and DeepArt offer co-creating algorithms to learners. They indicate how the generative interfaces push the limits of art by enabling exploration of style transfer, procedural generation, and real-time image generation. These systems contain constructivism learning as they encourage repetition, exploration and reflection.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Analysis of interaction patterns in art learning systems

This analysis has shown that there are different interaction patterns in digital art learning systems depending on the interface design and feedback mechanisms. There was increased involvement with direct manipulation and other adaptive interfaces which gave real-time visual or tactile feedback. The logs of interaction showed that they were experimenting with things iteratively, that is they were undoing and redrawing, adding and taking away layers, and customizing brushes, which is a sign of exploratory learning. VR painting tools and immersive platforms, on the one hand, promoted a more profound spatial cognition and, on the other hand, creativity.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Analysis of Interaction Patterns Across Digital Art Platforms |

||||

|

Evaluation Parameter |

Direct Manipulation Tools |

Immersive VR/AR Systems |

Generative AI Platforms |

Adaptive Art Software |

|

Average Interaction Duration

(minutes/session) |

42.6 |

58.3 |

47.1 |

53.8 |

|

Iterative Actions (Undo/Redo

per task) |

15.2 |

11.8 |

19.4 |

17.3 |

|

Interface Navigation

Efficiency (%) |

88.5 |

82.9 |

79.6 |

86.3 |

|

Real-Time Feedback

Utilization (%) |

91.2 |

88.4 |

84.7 |

92.1 |

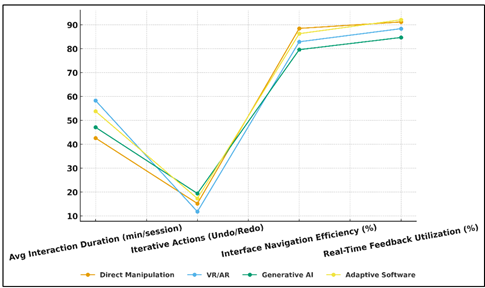

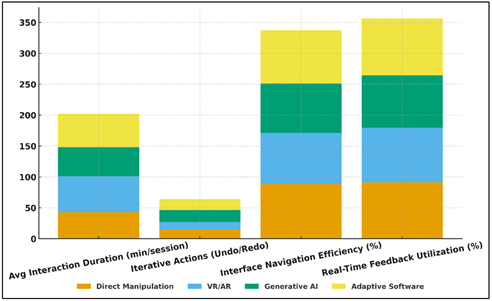

Table 2 results bring out the fact that there are major differences in interaction behavior of various digital art platforms, which are affected by the design paradigm of HCI. The highest average interaction (58.3 minutes) was documented in immersive VR/AR systems, which have a sense of immersion in space and invite more creative ideas to be explored. Figure 3 compares the performance of interaction and feedback with digital art tools.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Interaction and Feedback Performance Across Digital Art Tools

Also in adaptive art software, there was exhibited long interaction times (53.8 minutes), highest rate of real time feedback utilization (92.1%), and consequential pedagogical significance of adaptive responsiveness to maintain learner motivation and creative flow.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Evaluation of Interaction Metrics in HCI-Based Digital Art Platforms

The interface navigation efficiency (88.5% by direct manipulation tools) demonstrated the intuitive design and familiarity of the direct manipulation tools to the students who already had familiarity with the traditional art processes. Figure 4 presents the evaluation trends of interaction measures in digital art platforms based on HCI. Conversely, the generative AI platforms demonstrated the greatest rate of iterative behavior (19.4), which is indicative of reflective interaction by experimentation with the output of a given algorithm.

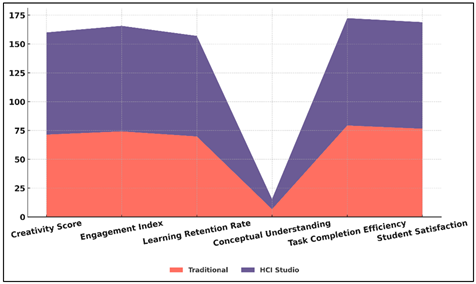

5.2. Impact on Student Creativity, Engagement, and Learning Outcomes

The results indicated that the learning environment that was integrated with HCI greatly increased the creativity and engagement in students and their performance in general. There was an increased self-efficacy and self-refinement through adaptive feedback and emotional connection with multimodal interfaces and cognitive immersion. Measures of creativity; like originality, compositional complexity and aesthetic coherence were significantly improved as compared to classroom settings in the past. Students found their interfaces being more motivating and confident in reaction to their artistic gestures and choices made in an inductive manner. Further, the immersive and generative instruments promoted convergent thinking, which encouraged the experimentation of alternative methods. Analytics of learning showed rapid conceptual learning, less task exhaustion and better retention. Altogether, these solutions confirm that HCI-based digital art education can make learners active producers and improve technical skills and expressive qualities with the help of interactive, adaptive and sensorial digital environments.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Quantitative Evaluation of HCI Impact on Creativity and Learning Outcomes |

|||

|

Evaluation Metric |

Traditional Classroom |

HCI-Based Digital Studio |

Improvement (%) |

|

Creativity Score (0–100

scale) |

71.4 |

88.6 |

24.1 |

|

Engagement Index (%) |

74.2 |

91.5 |

23.3 |

|

Learning Retention Rate (%) |

69.8 |

87.2 |

24.9 |

|

Conceptual Understanding

(0–10 scale) |

6.7 |

8.9 |

32.8 |

|

Task Completion Efficiency

(%) |

79.3 |

93.1 |

17.4 |

|

Student Satisfaction Level

(%) |

76.5 |

92.4 |

20.8 |

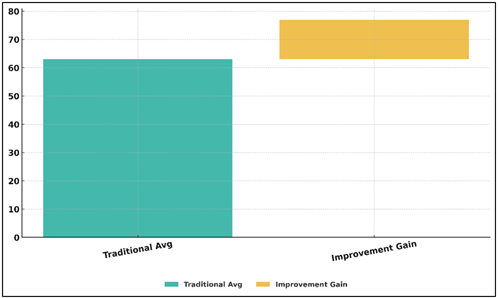

As the results in the Table 3 show, creativeness, engagement, and overall learning effectiveness increase significantly when principles of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) are applied to the art learning process. Interactive, adaptive, and multimodal tools also contribute to better originality and experimentation as shown by a 24.1% increase of the Creativity Score of 71.4 to 88.6. Figure 5 indicates that performance is different between the traditional learning and HCI enhanced studio environments. The Engagement Index as well as the Learning Retention Rate increased more than 23 percent indicating that responsive interfaces and instantaneous feedback systems maintain attention and enhance the long-term memory.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Comparison of Traditional vs. HCI Studio Learning Performance

The greatest improvement, of 32.8, was expressed in Conceptual Understanding, which confirms that there is a deeper level of cognitive processing and understanding of the principles of art through visual interaction and experience. Higher Task Completion Efficiency (17.4%) and Student Satisfaction (20.8) indicate the usability and emotional appeal of platforms that are hci-driven and which relieve creative frailty and motivate independence.

Figure 6

Figure 6 Improvement Flow from Traditional to HCI-Based Learning Models

In Figure 6, the transition between traditional and HCI based learning can be seen to have progressive improvements. Comprehensively these quantitative gains show that digital studios that are modeled with HCI frameworks do not only improve performance measures, but also create opportunities to enhance intrinsic motivation and reflective creativity making art education become a more participatory, adaptive, cognitively rich process.

6. Conclusion

The concept of embedding Human Computer interaction (HCI) models into art pedagogy is an epigenetic change in the convergence of creativity, learning and technology in the educational practice. Through interface design, cognitive psychology, and the art theory, HCI subverts the studio to be an interactive, adaptive, and sensory-based learning setting. The results of the research confirm that the digital art platforms based on the HCI principles including usability, feedback, multimodality, and adaptability positively contribute to the increase in artistic involvement and cognitive growth. Students shift toward less passive learning in favor of more tacit learning as they engage in dynamic interaction with digital systems, which react to their gestures, will and aesthetic choices. Direct manipulation, immersive environments and generative interfaces allow students to perceive art-making as a conversation between human perception and machine intelligence. This is enhanced by adaptive learning systems which provide real- time feedback that reinforces skill learning, imaginative confidence, and problem solving skills. Multimodal interfaces enhance the engagement and interaction of senses and emotions even more, strengthening the relationship between perception and expression, as well as conceptual knowledge. The research comes to a conclusion that HCI-based art education not only promotes digital literacy but also required creative professional skills such as critical and reflective thinking, which are crucial in the 21st century. It promotes inclusivity through the ability to support different learning styles and requirements to access, so that digital creativity will be open, collaborative and human-centered.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abdulai, M., Ibrahim, H., and Latif Anas, A. (2023). The Role of Indigenous Communication Systems for Rural Development in the Tolon District of Ghana. Research in Globalization, 6, Article 100128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2023.100128

Angeli, D. D., Finnegan, D. J., Scott, L., and O’Neill, E. (2021). Unsettling Play: Perceptions of Agonistic Games. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 14, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3431925

Bartelds, H., van Boxtel, C., and Savenije, G. M. S. (2020). Students’ and Teachers’ Beliefs About Historical Empathy in Secondary History Education. Theory and Research in Social Education, 48, 529–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1808131

Berger, S., and Kansteiner, W. (2021). Agonistic Perspectives on the Memory of War: An Introduction. In S. Berger and W. Kansteiner (Eds.), Agonistic perspectives on the Memory of war (1–11). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86055-4_1

Carthy, S., Cormican, K., and Sampaio, S. (2021). Knowing Me Knowing You: Understanding User Involvement in the Design Process. Procedia Computer Science, 181, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.113

Chang, E., Cai, S., Feng, P., and Cheng, D. (2023). Social Augmented Reality: Communicating Via Cultural Heritage. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 16, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3582266

Duranti, D., Spallazzo, D., and Petrelli, D. (2024). Smart Objects and Replicas: A Survey of Tangible and Embodied Interactions in Museums and Cultural Heritage Sites. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 17, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3631132

Falk, J. H., and Dierking, L. D. (Eds.). (2018). Learning from Museums (2nd ed.). Rowman and Littlefield.

Gates, E. F. (2024). Rich Pictures: A Visual Method for Sensemaking Amid Complexity. American Journal of Evaluation, 45, 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/10982140231204847

Gisby, A., Ross, C., Francis-Smythe, J., and Anderson, K. (2023). The “Rich Pictures” Method: Its Use and Value, and the Implications for HRD Research and Practice. Human Resource Development Review, 22, 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843221148044

Lazem, S., Giglitto, D., Nkwo, M. S., Mthoko, H., Upani, J., and Peters, A. (2022). Challenges and Paradoxes in Decolonising HCI: A Critical Discussion. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 31, 159–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-021-09398-0

Lin, M.-Y., and Chang, Y.-S. (2024). Using Design Thinking Hands-On Learning to Improve Artificial Intelligence Application Creativity: A Study of Brainwaves. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 54, Article 101655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101655

Pescarin, S., Bonanno, V., and Marasco, A. (2023). Social Cohesion in Interactive Digital Heritage Experiences. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7(6), Article 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7060061

Petrelli, D., and Roberts, A. J. (2023). Exploring Digital Means to Engage Visitors with Roman Culture: Virtual Reality vs. Tangible Interaction. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 16, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3625367

Toner, J., Desha, C., Reis, K., Hes, D., and Hayes, S. (2023). Integrating Ecological Knowledge into Regenerative Design: A Rapid Practice Review. Sustainability, 15(17), Article 13271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713271

Wang, Y. (2024). Becoming a Co-Designer: The Change in Participants’ Perceived Self-Efficacy During a Co-Design Process. CoDesign. Advance online publication, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2024.2362327

Zhang, L., and Shen, T. (2024). Integrating Sustainability Into Contemporary Art and Design: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Sustainability, 16(15), Article 6539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156539

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.