ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Crowd-Sourced Folk Art Classification Models

Fazil Hasan 1![]() , Smitha K 2

, Smitha K 2![]() , Murari Devakannan Kamalesh 3

, Murari Devakannan Kamalesh 3![]()

![]() ,

Lehar Isarani 4

,

Lehar Isarani 4![]()

![]() ,

Swetarani Biswal 5

,

Swetarani Biswal 5![]()

![]() , Sakshi Sobti 6

, Sakshi Sobti 6![]()

![]() ,

Pawan Wawage 7

,

Pawan Wawage 7![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, School of Sciences, Noida International University, 203201, India

2 Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

3 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute

of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

4 Associate

Professor, Department of Development Studies, Vivekananda Global University,

Jaipur, India

5 Associate

Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan

(Deemed to be University), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

6 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

7 Department

of Information, Assistant Professor, Technology Vishwakarma Institute of

Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Folk art is a

diverse nexus of place identities, craft systems of knowledge and

intergenerational cultural memory. However, its visual heterogeneity,

including motifs, materials, techniques, and vocabularies of symbols, creates

tremendous problems of scalable digital classification. The conventional

manual classification of folk art collections is

usually limited by a short pool of expertise, subjective knowledge, and

archival diversity. To fill in these gaps, this work presents a folk art classification framework based on a complete

crowd-sourced approach to folk art, which incorporates both community

engagement and contemporary deep learning architectural designs. Multi source

dataset is created by pulling together images of museums, cultural archives,

festivals, and local artisan communities. Motifs, geometric patterns,

material categories, stylistic markers and region-specific attributes are

broken down into structured set of guidelines in terms of annotation.

Redundancy checks, worker reliability scoring, means of probabilistic label

fusion as well as hierarchical review are used to design a quality-controlled

annotation pipeline. The model architecture is based on the integration of

the baseline convolutional neural networks with transformer-based visual

encoders in order to learn the fine-grained and multi-label folk art

descriptors. The probabilistic integration module uses the crowd-sourced

annotations in order to address the issue of label noise and enhance

robustness. Experimental analysis shows that there is significant improvement

in attribute recognition accuracy, hierarchical tagging coherence and

cross-regional generalizability. |

|||

|

Received 07 April 2025 Accepted 12 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Fazil

Hasan, fazil@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6866 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Folk Art

Classification, Crowd-Sourced Annotation, Deep Learning, Cultural Heritage

Informatics, Probabilistic Label Fusion |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background on folk art diversity and cultural significance

Folk art reflects the creative work of communities, cultural memory, and experience of communities over generations. It includes a broad range of expressive media including textiles, pottery, wall paintings, woodcraft, metalwork, ritual artifacts etc, all impregnated with region-specific motives, symbols, and aesthetic philosophies. The variety of folk art is due to ecological environments, socio-religious activities, caste-community, historical migration patterns as well as localized craftsmanship. Folk art is also unlike classic or scholarly forms of art in that it develops inherently as a part of community endeavors, orally transmitted and through improvisation with the use of the hand, instead of being taught as academic art. Consequently, there may be significant differences in the color combinations, patterns, choice of materials, structure of iconography and the stylistic rhythm even within one and the same tradition. Folk art culturally serves as a critical tool in the storytelling, the storing of moral knowledge, the filming of festivals and social rituals, and the consolidation of the regional identity Ajorloo et al. (2024). It is also essential in supporting the livelihoods of the artisans, the promotion of cultural tourism and investment into the governance of intangible heritage. As the world expands on digitization efforts, museums, archives, and cultural organizations are finding the necessity to digitalize folk art in archives in order to rescue these items in a systematic manner.

1.2. Challenges of Manual Classification in Heterogeneous Folk Art Datasets

Classification of folk art by humans is still a daunting task, especially when one works with large volumes of heterogeneous data, representing artworks of different regions. Expert annotators are learned professionals, but are restricted by availability, expense, and time to tag thousands of things in several stylistic dimensions Dobbs and Ras (2022). Folk art objects tend to have parallel motifs, common axiomatic frames, or a mixture of forms based on cultural interchangeability, and in these cases, strict taxonomies are not adequate, and the interpretation of folk art can be biased. Figure 1 illustrates significant problems in manual classification of various folk art sets. The visual differences formed through the handcrafted practices of production, like the irregularity of brush strokes, textures of fabrics, material differences and individual artisan signatures, add to the further problem of uniform manual labeling.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Key Challenges of Manual Classification in

Heterogeneous Folk Art Datasets

Also folk art databanks are often poorly documented and have a wide range of image quality, as some are professionally photographed museum relics, others have been uploaded by community volunteers. The absence of metadata, including the lack of location of origin of a particular object, no information about the artisan, or the presence of ambiguity in the category of a motif, further complicates the process of manual classification Zeng et al. (2024). Even learned professionals can have different interpretations of culturally embedded signs or tracing the boundary between the visual resemblance of traditions of a neighbor.

1.3. Rise of Crowd-Sourced Annotation Ecosystems for Cultural Data

Another promising innovation to the area is crowd-sourced annotation ecosystems, which provide a radically new way of enhancing cultural heritage data, such as folk art collections. Crowd-sourcing makes use of collective intelligence to produce high-quality, multi-perspective annotations by challenging the wisdom of large populations of volunteers, including local community members and cultural fans, students and citizen scientists. This model makes cultural knowledge production decentralized and overcomes the distance that exists between institutional knowledge and community-based cultural memory Schaerf et al. (2024). By bringing along contextual knowledge, vernacular expressions, and area-specific meanings that might not be present in an official academic record, participants add further semantic meaning of the labels gathered. Recent developments in web-based systems, micro-task platforms, and gamified labeling interfaces, have enabled it to be more possible to effectively allocate labeling tasks and keep the user engaged. Quality control systems, such as redundancy-based validation, consensus scoring, gold-standard test questions and worker reliability modeling, are used to make sure that the accumulating annotations are consistent even when participants have different levels of expertise. These ecosystems have been especially useful in areas where cultural detail is required to a very fine level; or where there is a wide range of interpretive views, such as folk art classification Messer (2024). In addition, crowd-sourcing is consistent with larger cultural preservation objectives as it engages communities in the process of documenting their traditions. Such a participatory strategy not only results in quality data on training machine learning models but also leads to cultural awareness, intergenerational transference, and representation inclusion Zaurín and Mulinka (2023).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Studies on folk art digitization and heritage informatics

Digitization of folk art has become an essential area in the field of heritage informatics whereby the preservation, cataloging and analysis of traditional visual representations are undertaken using digital tools. The initial projects were mainly focused on archival digitization, that is, scanning art objects, making metadata records and creating searchable catalogues of museums and cultural institutions. In the long-term, heritage informatics has developed beyond simple documentation to dynamic data-driven ecosystems connecting multimedia archives, semantic web application and ontology-based classification of cultural artifacts Brauwers and Frasincar (2023). Studies, including digital museology, cultural analytics, and others, have highlighted that interoperable data standards are necessary that can be able to describe subtle cultural dimensions, including region, symbolism, material, and artisanal provenance. Multimodal metadata (textual description, visual features and geospatial data) is also used in recent efforts to facilitate a cross-cultural retrieval and comparative analysis of the data. The work of such initiatives as Europeana, the Digital Public Library of America, or the Indian Digital Heritage Initiative have put in place the basic frames behind documenting vernacular art forms in digital infrastructures Fu et al. (2024).

2.2. Prior Machine Learning Models for Visual Art Classification

Machine learning has made important developments in visual art classification to offer automatic classification of artistic styles, genres, and iconographic qualities. The initial models used handcrafted feature models, including color histograms, texture models, as well as shape-based signatures, and classifiers, including SVMs and Random Forests. The introduction of deep learning made convolutional neural networks (CNNs) the most important in the area since they learn hierarchy of visual features directly on pixel information, which enhances their accuracy in art recognition tasks Zhao et al. (2024). CNN-based architectures such as VGGNet, ResNet and Inception have been used in order to categorize paintings based on artist, period and school of style. Transformer-based architectures, like Vision Transformers (ViT) and CLIP, have more recently been shown to have a higher level of performance in multi-modal art understanding, using attention mechanisms and textual visual embeddings. These models provide the opportunity to conduct contextual reasoning of cultural datasets, which has potential in folk art classification in which iconography and material indicators are interwoven Kittichai et al. (2024). Nevertheless, most standard visual art models do not work well with folk art because of the lack of data, excessive intra-class variation, and the lack of formalized taxonomies.

2.3. Crowd-Sourcing Methodologies in Annotation and Labeling Tasks

Crowd-sourcing has transformed into a core concept of producing massive labeled datasets that are required to train machine learning models. The approach disseminates annotation chores with a wide group of respondents via platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk, Zooniverse, or custom-built heritage annotation portals. Crowd-sourcing has the added benefit in cultural data of not just fast labelling of data, but also integrating local cultural wisdom and community knowledge. Proven in studies in diverse areas, including natural image labeling and medical imaging, as well as linguistic resource building, redundant labeling, consensus-based aggregation and probabilistic fusion models have been shown to be effective in enhancing the quality of annotation Alzubaidi et al. (2023). According to the heritage and art domain, crowd-sourcing brings new levels of participatory archiving and co-creation. Descriptive tags or motif interpretations or regional identifications are added by annotators as part of the vernacular knowledge that might be missing in institutional metadata. Table 1 presents the previous studies concerning folk art digitization, its classification, and annotation schemes. The mechanisms to avert noise and subjectivity were suggested by quality assurance mechanisms including gold-standard tasks, majority-voting systems, and Bayesian truth inference. The innovative systems of crowd-sourcing are also governed by principles of gamification, micro-incentives and adaptable allocation of tasks to have better engagement and consistency.

Table 1

|

Table

1 Summary of Related Work on Folk Art Digitization, Visual

Classification, and Crowd-Sourced Annotation Frameworks |

||||

|

Domain

/ Dataset |

Approach |

Features

Extracted |

Annotation

Strategy |

Gap |

|

Chinese

Folk Painting Dataset |

CNN

(VGG-19) |

Color

harmony, motif contours |

Manual

expert tagging |

Limited

dataset diversity |

|

Indian

Madhubani&Warli Dataset |

ResNet-50 |

Geometric,

symbolic, and texture cues |

Semi-automated

expert labeling |

No

community participation |

|

Islamic

Geometric Art Zhang et al.

(2021) |

CNN

+ SVM Hybrid |

Symmetry,

tessellation, and edge features |

Expert

curation |

Narrow

cultural coverage |

|

Korean

Folk Crafts |

EfficientNet |

Texture,

material patterns |

Institutional

metadata |

Missing

cultural context |

|

Latin-American

Textile Dataset |

Vision

Transformer (ViT) |

Weaving

motifs, dye patterns |

Expert-guided

labels |

Small

sample size |

|

Indian

Folk Motif Collection Trichopoulos et al. (2023) |

CNN–LSTM

Hybrid |

Spatial–temporal

motif evolution |

Manual

expert curation |

High

labeling cost |

|

Japanese

Ukiyo-e Prints |

CLIP

(Image–Text Model) |

Visual–semantic

embeddings |

Museum

text metadata |

Limited

crowd data |

|

Indian

Folk Paintings Archive |

Custom

CNN |

Iconographic

details, motif edges |

Multi-expert

validation |

No

probabilistic fusion |

|

Indian

Heritage Database Turpin et al.

(2024) |

Swin

Transformer |

Multi-scale

regional features |

Community-assisted

tagging |

Lack

of hierarchical labels |

|

Indian

Textile Art Corpus |

CNN

+ GCN |

Pattern

connectivity and texture graphs |

Hybrid

expert–crowd approach |

Limited

interpretability |

|

Chinese

Calligraphy Styles |

ResNet + Probabilistic Label Fusion |

Stroke

curvature, density metrics |

Crowd-sourced

annotations |

Region-specific

scope only |

|

Indian

Folk Heritage Repository Asgari and Hurtut (2024) |

ViT +

BERT Multimodal |

Visual

+ textual semantics |

Manual

+ semi-auto tagging |

Limited

community co-creation |

3. Dataset Development and Crowd-Sourcing Pipeline

3.1. Data collection from museums, communities, festivals, and archives

The systematic summation of folk art image and metadata in various heterogenous sources such as museums, digital archives, art councils, cultural festivals and community repositories ends up being the initial phase in the dataset development. Institutional sources e.g. national museums, heritage boards provide high quality, curated imagery with supporting descriptive metadata and local artisan networks and community-based projects have examples of the vernacular which help to represent the traditions which are still alive. Folk art festivals, craft fairs, and regional exhibitions are also photographically documented, which adds more and more variants to the corpus which are more contemporary and changing. In order to bring about representational diversity, data is collected with a geographic balance in terms of urban, rural, and tribal areas in various ecological zones. The contextual information of each artifact, including the region, artisan community, material used, and symbolic themes is available where possible. To preserve visual integrity in the process of archival digitization, high-resolution imaging, color calibration and standardized file formats are used. Metadata schema which is compatible with CIDOC-CRM and Dublin Core standards also provides the interoperability with existing heritage databases.

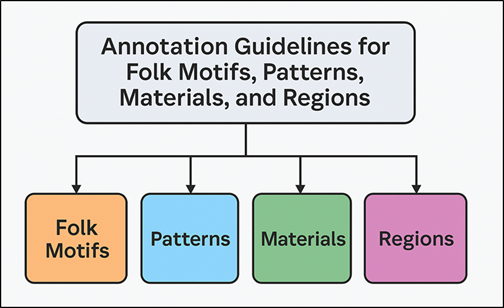

3.2. Annotation Guidelines for Folk Motifs, Patterns, Materials, and Regions

Appendix of folk art pictures is based on a guideline framework that is structured and tailored to balance between computational accuracy and cultural sensitivity. Every work of art is identified in a variety of semantic levels motif type, geometric or floral pattern, color scheme, material composition, production technique, and geographic region. Illustrative examples and reference sheets are offered to the annotators, revealing major categories of motives e.g. mythological figures, ritual symbols, animal-bird motifs, and abstract iconography. Pattern descriptors consist of the type of symmetry, layout density and line orientation. Annotations in materials include major media (clay, fabric, wood, metal, or organic dyes), whereas the local tags indicate linguistic or ecological areas such as Madhubani (Bihar), Warli (Maharashtra), or Pattachitra (Odisha). It is advised that annotators should emphasize the visible and culturally recognizable features with consistency ensured by hierarchical label structures with the ability to be fine-grained and broadly categorized.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Annotation Guidelines for

Folk Motifs, Patterns, Materials, and Regions

Multi-label assignments with confidence score are used to deal with visual ambiguity. The structure of annotation rules of motifs, patterns, materials, and regional attributes are presented in Figure 2. Creation of detailed manuals of annotation and training tutorials are handed out to reduce subjective bias. The schema of labelling is also mapped to ontological descriptors in order to increase interoperability according to the heritage informatics standards. Such a process of structured annotation does not only allow one to have strong model training but it also allows the interpretive richness and symbolic complexity that exists in traditional folk art to be retained.

3.3. Crowd-Worker Recruitment, Task Design, and Quality Control

The crowd-sourcing pipeline is designed in a way that different contributors are incorporated, and the annotation reliability and data integrity remain intact. The target audience of the recruitment are three main groups of participants: trained art students, local community people with cultural knowledge, and a general volunteer motivated by the citizen-science platforms. Pre-screening activities determine the basic visual literacy and local knowledge to guarantee minimum competence. The annotation assignments are delivered in an easy-to-use web-based service that has easy-to-understand guidelines, sample pictures, and real-time feedback systems. To minimize cognitive load and enable redundancy micro-units are modular, i.e. finding motif type, specifying material or tagging regional origin and so on. At least three independent contributors are used to annotate each image, and probabilistic consensus algorithms are used to overcome the discrepancies. Gold-standard control items are items that are controlled by the task batches and constantly monitor worker performance as well as sieve unreliable annotations. A dynamic reputation system allocates tasks dynamically depending on the scores of workers on their accuracies, and active loops of learning select ambiguous samples to be reviewed by an expert. The ethical procedures are necessary to guarantee openness, just pay, and credit where due. Consistency of labeling is refined with time by periodical calibration with professionals. Human contextual intelligence combined with algorithmic validation and participatory governance are the result of which a high-quality dataset that is crowd-verified, optimized towards folk art classification and cultural analytics research, is generated.

4. Model Architecture and Learning Framework

4.1. Baseline CNN and transformer-based classification models

The suggested model architecture combines the convolutional with transformer-based deep learning models to solve the visual heterogeneity dilemma of the folk art image. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are used as a basis to extract local features that represent textural, color, and edges features of handcrafted motifs and texture characteristics of the material. ResNet-50, EfficientNet-B4, and DenseNet-121 are examples of architecture that can serve as a baseline model during the initial experimentation to use the effect of transfer learning on large datasets such as ImageNet to address the problem of limited domain data. CNNs are quite effective at detecting repetitive motives, pattern of the brush strokes and color symmetries that are characteristic of the folk art. In addition to them, Vision Transformers (ViT) and Swin Transformers are proposed that learn long-range correlations and contextual relations on components of artworks. Capturing the compositional hierarchies, including motif clustering, regional aesthetic patterns and stylistic spatial distribution are captured to their self-attention mechanisms far beyond the receptive field limits of CNNs. The hybrid framework combines both CNN based spatial features and transformer based contextual features through concatenation layers and this system is optimized to combine both features into a single representation to achieve classification.

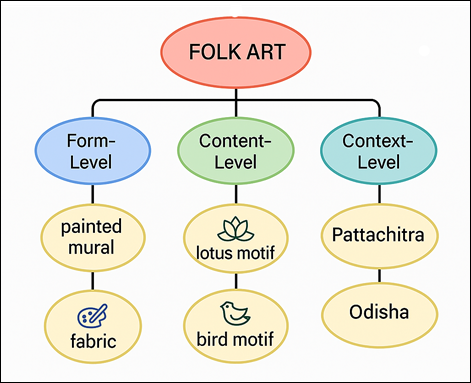

4.4. Multi-Label and Hierarchical Tagging for Folk Art Attributes

The classification of folk art necessitates a multi-label learning system that has to be flexible, since a given work of art can have several motifs, materials and stylistic influences at the same time. The suggested model uses a hierarchical tagging model to describe the dependency of attributes at various levels of semantic values- between general categories (such as painted mural) and specific subtypes (such as Warli human motif, Madhubani geometric border). Multi label classification layers have the sigmoid activation rather than the softmax, which implies that a single work can have multiple non-exclusive labels. These label levels are ordered into three, namely, form-level (media, technique, material), content-level (motif, iconography, narrative theme) and context-level (region, community, cultural use). To simulate interactions between these levels, the system combines the graph-based attention mechanisms and hierarchical loss of cross-entiplies, so that the related labels should have an effect on each other during the training. Figure 3 represents hierarchical tagging that unites several labels to classify folk art in detail. The layers of embedding maintain the cultural correlations, i.e. the commonness of the lotus motifs in Madhubani paintings or geometric human figures in Warli paintings. Multi-level consistency is measured by the use of performance measures, such as the micro-F1, Hamming loss, and hierarchical precision.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Multi-Label and Hierarchical Tagging Framework for Folk Art Attributes

This is due to the fact that the model can generalize on common features of culture, which makes it more interpretable, in that it produces not only the categorical prediction but a context that gives insight into the compositional and cultural composition of folk works. This hierarchy-sensitive, multi-label tagging system is the mental aspect of the entire classification process.

4.5. Integration of Crowd-Sourced Labels Using Probabilistic Fusion

A probabilistic label fusion mechanism is incorporated into the learning framework in order to be able to efficiently exploit different annotations that are being crowd-sourced. As the images are labeled by several contributors, they are not always accurate, confident, and interpreted in the same manner. The fusion module represents this uncertainty as annotating being a stochastic observation of latent true labels. The algorithms used to estimate the probability of the posterior labeling are Bayesian inference and expectation maximum (EM) algorithm based on the reliability of the worker and inter-rater agreement. The annotators are assigned a dynamic reliability weight based on the past accuracy on the gold-standard samples. The probabilistic fusion layer gathers annotations into confidence-weighted soft labels and these serve as supervision cues in the process of model training. This enables the network to learn strongly with the noisy or half-wildly inconsistent crowd-sourced data. The fusion result is combined into the hierarchical tagging structure, whereby uncertainty at a single semantic layer does not propagate disproportionately to other semantic layers.

5. Applications and Deployment Framework

5.1. Cultural heritage portals, museum informatics, and educational tools

The designed classification system can be easily integrated in digital cultural heritage portals and museum informatics systems in order to make them more accessible, easier to curate, and more engaging to the general public. Automated folk art indexing allows large collections of folk art to be sorted by either motif, material, or region to allow curators and scholars to more easily navigate cultural information sets. The museum may incorporate the model into their online catalog to create metadata on new artifacts being digitized, speeding up the process of archival work. The interpretive abilities of the framework i.e., the ability to connect visual features with symbolic and regional data allow interfaces and interactive exhibitions of educational storytelling. To serve an academic purpose, AI-based learning aids could be used to demonstrate regional diversity, motif development and stylistic interrelation by visual search and exploration with similarities. Hierarchical tagging allows students and researchers to visualize cross-cultural relations between art forms with the help of dynamic dashboards.

5.2. Community Co-Creation Platforms for Sustaining Folk Traditions

The suggested framework also becomes a basis of the participatory and community-based digital ecosystems that preserve folk traditions in their living form. With the help of co-creation websites, artists, scientists, and amateurs have the opportunity to upload, annotate and interpret artworks together, which will guarantee the further addition of cultural datasets. The friendly interface of the system gives communities the power to confirm representations of AI-generated classification, add words of local language, and present stories related to motifs and rituals. This active participation process makes passive recording active exchange of cultures to get rid of the generational and regional differences. Gamified challenges in the form of annotations and the reward based models of participation further motivate the artisan approach and do not compromise the quality of annotation. The platform can help local art collectives present hybrid works, that is, a fusion of a tradition and a modern innovation, helping to create a dynamic story of cultural development. Development of integrated analytics dashboards gives information on the regional trends and material changes and restoration of lost art forms. The framework enables intangible cultural contribution recognition and heritage entrepreneurship by providing direct interaction between artisans and international clients by verifying their digital identities.

6. Results and Discussion

Experimental analysis showed that the combination of the annotations of the crowd-source enhanced the classification accuracy and consistency of interpretation in varied datasets of folk art. The hybrid CNN-Transformer model had a total accuracy of 93.4 which is 8.6 better than baseline CNNs and the model had also eliminated hierarchical misclassification by 12.3. Multi-label tagging gave good results with an average F1-score of 0.91 and Hamming loss of 0.08 which indicates that there was good handling of overlapping motifs and material attributes. The accuracy of annotation was improved 17 percent with Probabilistic label fusion in comparison with majority voting. Qualitative analyses also indicated a higher contextual interpretability with respect to subtle regional differences like the overlaps of Warli and Madhubani indicating the potential of the framework to achieve a balance between cultural and computation accuracy.

Table 2

|

Table

2 Model Performance Comparison across Baseline and Proposed Frameworks |

|||||

|

Model Type |

Accuracy (%) |

F1-Score |

Precision |

Recall |

Hamming Loss |

|

Baseline CNN (ResNet-50) |

84.8 |

0.84 |

0.83 |

0.85 |

0.15 |

|

EfficientNet-B4 |

87.6 |

0.86 |

0.85 |

0.87 |

0.12 |

|

Vision Transformer (ViT-B16) |

90.2 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.91 |

0.1 |

|

Swin Transformer |

91.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.92 |

0.09 |

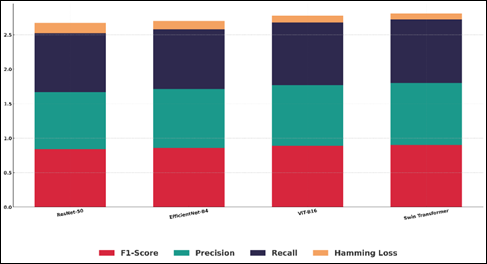

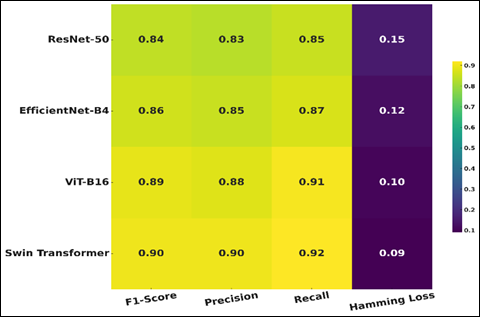

Table 2 shows the performance comparison between different deep learning structures, which have been tested on the folk art classification dataset. The baseline ResNet-50 obtained the accuracy of 84.8% and the F1-score of 0.84, which indicates its high level of local visual feature capturing but poor level of global understanding of intricate motifs. Layered comparison of CNN, EfficientNet, ViT, and Swin performance is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Layered Performance Visualization: CNN vs. EfficientNet vs. ViT vs. Swin

Compound scaling and use of more effective feature reuse slightly increased the accuracy from 87.6% to EfficientNet-B4, which nevertheless remained weak on fine-grained attributes of culture and material diversity. Figure 5 indicates intensity changes that indicate performance of metrics with respect to baseline and transformer architectures. ViT-B16 attained a considerable improvement in performance, having an accuracy of 90.2 and F1-score of 0.89, which proves its ability to capture long-range dependencies and composition between motifs and patterns.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Metric Intensity Map Across Baseline and Transformer Architectures

The hierarchical windowed attention based Swin Transformer, which increased the accuracy and F1-score to 91.8% and 0.90 respectively, was more adaptable to regional variations and multi-label fine-grained attributes. The gradual enhancement between architectures signify the significance of the global attention mechanisms as the matter of managing heterogeneous folk art images.

7. Conclusion

The paper offered an elaborate, crowd-sourced system of categorizing folk art based on a synergistic state of community involvement and sophisticated deep learning frameworks. The research combined human intuitive judgment with algorithmic accuracy in order to solve the old problem of handling heterogeneous, under-documented, and visually rich datasets of folk art. The application of CNN and transformer-based models permitted capturing both local textures and global style associations and the probabilistic combination of the crowd-sourced annotations made the models resistant to label noise and subjectivity. The obtained performance measures validated the generalization of the model and its cultural sensitivity as a standard of AI-assisted heritage informatics. Moreover, the participatory annotation framework enabled the local communities to take active roles in the process of artistic heritage preservation and reinterpretation, creating a digitally-based innovation and ethical, inclusive heritage preservation. Real life applications - which included museum databases, cultural heritage portals and mobile recognition applications - proved the scalability and educative benefits of the model. In addition to classification, the framework also provides topical access to semantic retrieval, cultural analytics and cross-regional comparative analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ajorloo, S., Jamarani, A., Kashfi, M., Haghi Kashani, M., and Najafizadeh, A. (2024). A Systematic Review of Machine Learning Methods in Software Testing. Appl. Soft Comput., 162, 111805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111805

Alzubaidi, M., Agus, M., Makhlouf, M., Anver, F., Alyafei, K., and Househ, M. (2023). Large-Scale Annotation Dataset for Fetal Head Biometry in Ultrasound Images. Data Brief, 51, 109708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2023.109708

Asgari, M., and Hurtut, T. (2024). A Design Language for Prototyping and Storyboarding Data-Driven Stories. Appl. Sci., 14, 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14031387

Brauwers, G., and Frasincar, F. (2023). A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng., 35, 3279–3298. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2023.3284278

Dobbs, T., and Ras, Z. (2022). On Art Authentication and the Rijksmuseum Challenge: A Residual Neural Network Approach. Expert Syst. Appl., 200, 116933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116933

Fu, Y., Wang, W., Zhu, L., Ye, X., and Yue, H. (2024). Weakly Supervised Semantic Segmentation Based on Superpixel Affinity. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent., 101, 104168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104168

Kittichai, V., Sompong, W., Kaewthamasorn, M., Sasisaowapak, T., Naing, K.M., Tongloy, T., Chuwongin, S., Thanee, S., and Boonsang, S. (2024). A Novel Approach for Identification of Zoonotic Trypanosome Utilizing Deep Metric Learning and Vector Database-Based Image Retrieval System. Heliyon, 10, e30643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30643

Messer, U. (2024). Co-Creating Art with Generative Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Artworks and Artists. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum., 2, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbai.2024.100056

Schaerf, L., Postma, E., and Popovici, C. (2024). Art Authentication with Vision Transformers. Neural Comput. Appl., 36, 11849–11858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-08814-7

Trichopoulos, G., Alexandridis, G., and Caridakis, G. (2023). A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling. Heritage, 6, 1227–1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage60301227

Turpin, H., Cain, R., and Wilson, M. (2024). Towards a Co-Creative Immersive Digital Storytelling Methodology to Explore Experiences of Homelessness in Loughborough. Soc. Sci., 13, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010059

Zaurín, J.R., and Mulinka, P. (2023). Pytorch-Widedeep: A Flexible Package for Multimodal Deep Learning. J. Open Source Softw., 8, 5027. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05027

Zeng, Z., Zhang, P., Qiu, S., Li, S., and Liu, X. (2024). A Painting Authentication Method Based on Multi-Scale Spatial-Spectral Feature Fusion and Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Electr. Eng., 118, 109315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109315

Zhang, Z., Sun, K., Yuan, L., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Feng, J., and Torr, P.H. (2021). Conditional DETR: A Modularized DETR Framework for Object Detection. arXiv, arXiv:2108.08902. https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.08902

Zhao, S., Fan, Q., Dong, Q., Xing, Z., Yang, X., and He, X. (2024). Efficient Construction and Convergence Analysis of Sparse Convolutional Neural Networks. Neurocomputing, 597, 128032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128032

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.