ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Fusion of Cultural Heritage and AI in Sculptural Reproduction

Jyoti Saini 1![]()

![]() ,

N. Srinivasan 2

,

N. Srinivasan 2![]()

![]() ,

Fehmina Khalique 3

,

Fehmina Khalique 3![]() , Shailesh Solanki 4

, Shailesh Solanki 4![]()

![]() ,

Kalpana Munjal 5

,

Kalpana Munjal 5![]()

![]() ,

,

Rajesh Raikwar

6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, ISDI - School of Design and Innovation, ATLAS SkillTech

University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute

of Science and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

3 Uttar

Pradesh 201306, India

4 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University

5 Associate

Professor, Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

6 Electrical

Engineering Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Cultural

heritage and artificial intelligence have brought art reproduction to a new

level of sophistication, which is data-driven and capable of rendering a

sculpture with a high level of accuracy, interpretability, and preservation

value. Manual production and interpretation has been

the main source of traditional sculptural replication that caused

inconsistency and restrictions in restoring fragmented or eroded artifacts.

Recent developments of 3D scanning, photogrammetry, multispectral imaging,

and archival digitization have allowed the high-resolution acquisition of

geometric, textural, and material characteristics that make strong datasets

to be used in computational reconstructions. In this paper, a deep learning

architecture, generative, and shape-completion networks, are combined to

achieve a unified framework that can be used to improve sculptural

restoration workflows. AI-based approaches facilitate automated derivation of

features, the identification of historical motifs and the forecastive

modeling of missing or degenerated areas on the context-sensitive basis.

Neural rendering also enhances the recovery of texture in order to generate

material properties that are in line with the known cultural aesthetics. The

hybrid digital-physical pipeline suggested in this paper will include the use

of both automatic reconstructing and manual handover by artisan knowledgeable

input, which will guarantee the appropriateness of the cultures and the

faithfulness of the style. The technologies of additive manufacturing,

robotic milling, and high-precision fabrication allow the physical

implementation of the models created by AI and preserve the integrity of

structures and visual quality. There is a multi-criteria fidelity assessment

model which is based on geometric accuracy, visual realism, historical

validity and material coherence. |

|||

|

Received 16 April 2025 Accepted 22 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Jyoti

Saini, jyoti.saini@atlasuniversity.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6862 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cultural

Heritage Preservation, AI-Driven Reconstruction, Generative Models, 3D

Scanning, Neural Rendering, Sculptural Reproduction |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Cultural heritage is one of the best examples of human creativity, identity and civilization. Sculptures are considered to be the most artistic and technical work of the given time because, being the most stable records of historical events, stylistic traditions, and religious beliefs, they are considered to be the everlasting archives. Nevertheless, conservation of the artifacts in sculpture is increasingly threatened by the deterioration of the environment, as well as wear and tear, natural calamities and human destruction. Although invaluable, traditional methods of restoration are frequently subjective and labour-intensive and unable to reproduce finer detail or recreate badly damaged areas. In these regards, the meeting of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital heritage technologies is an innovative possibility to rethink the way sculptural heritage is examined, rebuilt, and distributed Acke et al. (2020). Computational restoration is based on the fact that with the introduction of digital technologies 3D scanning, photogrammetry, multispectral imaging, it is possible to capture the geometry, texture, and material properties of a surface precisely in the digital form. However, data capture is not the end; data interpretation and reconstruction of incomplete or erased areas require a cognitive process, which is capable of being replicated through AI learning by using massive cultural datasets. Contemporary deep learning and generative models include autoencoders, variational networks, and diffusion-based architectures have the ability to predict the patterns and styles of contexts as well as morphological symmetries that characterize particular cultural periods or artistic movements. Introducing such models into the process of sculptural reproduction, researchers will be able to go beyond the immobile digitization and create an intelligent restoration that did not distort the artistic values and historical authenticity Khan (2024). The reconstruction of artworks by AI is supposed to fill the gap between the physical pieces of art and their digital copies. Shape-completion Learners Shape-completion networks are trained on small 3D examples of complete sculptures to learn how to plausibly generate geometry in remains and neural rendering models are taught to attain surface detail and color based on material-specific prior knowledge. This computational intelligence is not only enhancing visual fidelity, it offers non-invasive methodology of restoration, which requires fewer manual operations and possibilities of misinterpretation Leshkevich and Motozhanets (2022). Multimodal AI elements that work together to reconstruct entire sculptural heritage are depicted in Figure 1. Notably, refinements of these reconstructions can be made in the context of a humanhuman-AI joint venture, in which artisans, historians and conservators can influence the AI outputs to be culturally sensitive and stylistically sound.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Multimodal AI-Integrated Framework for Sculptural Heritage Reconstruction

No less important is the part of additive manufacturing and robotic sculpturing which transforms digital reconstructions into accurate physical models. Given a combination of the digital accuracy of AI-made models and the sense of tactile mastermanship of master craftsmen, one will be able to recreate the missing masterpieces to an unprecedented level of accuracy. Reproduction can have several functions: they substitute delicate originals in displays, increase access to education, and allow the experience of a museum to be interactive Ghaith and Hutson (2024).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional approaches to sculptural reproduction

Traditional artisanal reproduction and restoration methods of sculpture have been based on a method of sculpture reproduction and restoration based on the traditional method of mold-making, casting, carving and manual sculpture based on the traditional method of craft, tactile/haptic ability and material know-how. One of the most popular methods of classical art is plaster casting, a process of making piece-molds in plaster or other substances using a soft original (usually clay), then removing the mold and casting plaster, resin or other media into it to make a copy Zhong et al. (2021). Lost-wax (cire-perdue) casting, a technique that was much used in sculptures of metals, was also used by sculptors: a wax original is placed in a mold, and a fire is lit to burn the mold, leaving the mold filled with molten metal. Nevertheless, although it is robust in most cases, conventional reproduction methods have trade-offs. Casting and manual molding - particularly large and intricate sculptures - are human intensive, time-consuming and subject to human error. In multi-part piece molds, matching and reconnecting parts in the appropriate place is a sensitive undertaking, and any imprecision could result in deformities or missing of detailed features He et al. (2017).

2.2. Advancements in digital heritage technologies (3D scanning, photogrammetry)

Digital heritage technologies have seen a shift in heritage conservation in the last few decades. The use of high-resolution 3D scanning (laser scanning, structured light scanning) and photogrammetry has made it possible to capture sculptures, monuments, and architectural heritage with the highest level of accuracy, geometry, texture and surface detail with no chance of damaging delicate originals Song (2023). An example is the Digital Michelangelo Project (Stanford University / University of Washington), multi-angle laser scans of large statues, including by masters as Michelangelo, to create textured 3D meshes, which captured the marks of the chisels and surface curves, and color details. On the same note, international projects like Zamani Project have used terrestrial laser scan, photogrammetry and GIS-based documentation to document whole heritage sites and landscapes - transforming them into archivable quality 3D and space data to be reused in future restoration or analysis Xu et al. (2024). Such techniques can be used to thoroughly digitally recad the not just the sculptures but the buildings, monuments, and cultural landscapes as well. Digital heritage technologies are unlimited by the numerous constraints associated with traditional casting: they are non-invasive, extremely precise to study, and can be analyzed, being measured, studied in deformations, and reproduced at other scales. They advocate an archival collection of heritage over time - although the material original may be damaged or destroyed by time or war or calamity.

2.3. AI applications in cultural preservation: global case studies

Artificial intelligence (AI) has started to become more of a transformative force in preservation of cultural heritage in the past few years, not only by digitizing but also by intelligently analysing, recreating, and restoring artifacts and monuments. The literature on successful applications has been growing: automated damage detection and structural assessment, generative reconstruction of missing parts and texture restoration have been successful. As an example, the recent 3D restoration methods using deep learning can restore damaged artifacts: networks with this technique can be trained on pre-existing 3D models and, with this aid, reconstruct missing geometry, making visually plausible digital restorations Ye (2022). Generative AI systems are currently being applied to reconstruct heritage buildings and sculptures even in cases where only a limited and degraded data is present. In even more accessible studies, like Oitijjo-3D, which was reviewed in 2025, unnecessary amounts of publicly available images (e.g., street-view, archival photos) are utilized with the help of multimodal reasoning to produce 3D models, and hence, heritage reconstruction is democratized in a resource-constrained setting. Moreover, neural rendering based on AI and more sophisticated modeling systems, such as neural radiance fields (NeRF), have been used in creating photorealistic 3D renderings of the architectural and sculptural heritage as a way to support the conservation efforts and immersive virtual access [10]. In addition, AI can be used to perform constant surveillance and preventive conservation: image recognition, pattern detection, or automated environmental sensors predictive analytics can be used to determine structural vulnerabilities, weathering patterns, or initial signs of degradation - in order to respond and maintain in time. Table 1 provides an overview of digital and AI based methods of reconstructing heritage, strengths and limitations. Naturally, worldwide projects like Rekrei (previously Project Mosul) have utilized crowdsourced photographic information with computational reconstruction to revive objects lost in a war, and therefore available as digital analogues to preserving heritage and collective memory.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on Digital &

AI-Based Heritage Reconstruction |

|||

|

Region

/ Culture |

Data

Acquisition |

Computational

Technique |

Advantages |

|

Italian

Renaissance sculptures (e.g., David, Medici tombs) Hou et al. (2022) |

High-resolution

laser scanning + color photography |

Range-finder

scanning + mesh alignment/merging software |

Very

high geometric fidelity (sub-mm), captures even chisel marks; establishes

benchmark for digital preservation |

|

Archaeological

objects / fragments — pottery, small artifacts Cliggett and Pedersen (2021) |

Partial

3D scans / incomplete meshes |

Generative

Adversarial Network (GAN)-based voxel completion |

Demonstrates

data-driven shape completion for cultural heritage; automates restoration of

partial objects |

|

Archaeological

fragments / heritage objects (varied origin) |

Partial

3D point clouds / fragments |

Hybrid

auto-completion network (3D fragment completion + self-supervised learning) |

End-to-end

automation; reduces dependency on manual intervention; improves restoration

workflow efficiency |

|

Architectural

heritage (monuments, buildings) — large scale Heersmink (2023) |

Laser

scanning + photogrammetry + aerial/terrestrial imagery |

SfM +

mesh generation + texture mapping + post-processing |

Demonstrates

scalable pipeline for large-scale heritage with textures; efficient for

monuments and sites |

|

Digital

sculptures / heritage artifacts (varied origin) |

Partial

scans / incomplete meshes + partial texture data |

Masked

Autoencoder for shape + texture recovery |

Simultaneous

recovery of geometry and texture; improved texture realism; suitable for

damaged/missing data scenarios |

|

Museum

artifacts / heritage sculptures |

High-precision

3D scanning (micrometer scale) |

Laser

scanning + high-detail post-processing |

Captures

very fine surface details; suitable for conservation-quality replicas |

|

Relief

sculptures / site-based reliefs (various heritage contexts) Li et al.

(2023) |

Single

or monocular images (e.g., photos) |

Deep

monocular reconstruction + generalization techniques |

Applicable

where only 2D images exist; accessible; low hardware demand; useful for sites

with limited data |

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Data acquisition: 3D scans, multispectral imaging, archival datasets

AI-aided sculptural reproduction is based on the principles of accurate and thorough data capture including the physical geometry of an object and the cultural content of artifacts including the surface features of chisel marks, curvature and erosion patterns recorded in densely populated point clouds. In heritage, non-contact based scanning is used to ensure mechanical stress is not exerted on delicate items Takimoto et al. (2021). The resultant scans are superimposed and combined to become dense polygonal meshes that depict the entire three dimensional morphology of the sculpture. In addition to the use of geometric capture, multispectral imaging and hyperspectral imaging methods offer spectral data below and above the visible wavelengths (infrared, ultraviolet). These data layers indicate under surface features, remnants of pigments and variations in composition of materials that are not visible to the eye. This combination of geometrical data and spectral information constitutes a multimodal data that is essential in the reconstruction of materials by AI that is aware of materials Rinaldi et al. (2022). Also, archival records, such as historical images, curatorial records and previous records of restoration, are invaluable sources of context. They aided in the temporal comparison and stylistic interpretation, which means that AI models could predict missing or damaged areas in accordance with the initial aesthetic.

3.2. Preprocessing and Reconstruction Pipeline

After data acquisition, preprocessing converts raw data into natural and organized data that can be used in reconstruction using AI. Different scans are captured at various angles and point cloud alignment and registration start with the spatial amalgamation of the scans via an algorithm like Iterative Closest Point (ICP) or feature-based matching. Noise elimination followed by outlier filtering is then used to remove artifact due to the interference of the ambient or reflective surfaces. The processed point cloud is then represented using triangle meshes, using surface reconstruction algorithms such as Poisson triangulation or Delaunay triangulation, and has continuity between intricate geometrical contours. Thereafter, after cleaning their geometry, texture mapping combines both the color and spectral information onto the mesh by UV unwrapping. This step is the synthesis of the optical reality of the multispectral data with a structural reality of the 3D geometry. Mesh decimation and topology optimization are done so as to achieve balance between detail fidelity and computational efficiency to be followed by AI training or rendering. The refined data is then fed into the AI reconstruction step where a deep learning and generative model is used to do feature extraction, prediction of missing components, and texture reconstruction. When the data is not completely available, the shape-completion networks provide missing structures, which are provided under influence of the contextual clues and the principles of symmetry.

3.3. AI model selection

3.3.1. Deep learning

The sculptural data interpretation and reconstruction is based on deep learning models. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been shown to be especially effective at analyzing surfaces in 3D, gleaning fine-grained geometric and textural detail of multi-view imagery of a particular object or a voxelized model. CNN-based encoders are applied in sculptural restoration to acquire stylistic and morphological features of a period or artist. In the case of volumetric data, the use of 3D CNNs and point-based networks e.g. PointNet or KPConv is used to learn spatial continuity and curvature dynamics. Recurrent and attention based networks are expanded on this ability to temporal or sequential restoration problems with several scans or historical snapshots available. The networks are automated to recognize features, classify types of degradation and direct priorities in reconstruction. Deep learning models trained on mass cultural data guarantee both the regularity and accuracy of data analysis, which approximate the interpretation of experts, as well as aesthetic consistency and structural accuracy of restored statues.

3.3.2. Generative Models

Generative models can be used to perform creative inference, which means that machines can create missing or damaged sculptural detail not given as explicit input data. In a Generative Adversarial Network (GANs), the latent codes teach the shape, texture, and decoration that are cultural-fashionable and generate high-quality receptions of the original object. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are statistical distributions of form variations, which are used to predict plausible reconstructions through incomplete inputs. These models may acquire stylistic details, including drapery folds, relief patterns, tool mark motifs, etc. in reference datasets in sculptural reproduction. Generative models are able to maintain authenticity and increase realism by conditioning generation on familiar features or multi-spectral indications. Their creative versatility and probabilistic thinking can be invaluable in the tasks where interpretive reconstruction, but not a mere geometric copying, is necessary.

3.3.3. Shape-Completion Networks

Shape-completion networks are aiming at recovering lost geometric areas of injured or incomplete 3D scans. Contrary to the classical mesh interpolation, they study the contextual priors with the help of big data of complete sculptures, which allows them to estimate the plausible structure of obscured or eroded regions. Different architectures including 3D U-Net, PCN (Point Completion Network) and OccNet (Occupancy Network) are based on voxel, point cloud or implicit surface representations to forecast continuous, watertight shapes. In restoration of cultural heritage, shape-completion models have the ability to intelligently based on bridging the gaps without altering the stylistic continuity and surface smoothness. As an example, they are able to reconstruct the lost limbs, ornamental designs or foundational forms following the symmetry and cultural patterns which are acquired. Their output is further refined with adversarial fine-tuning or diffusion-based fine-tuning with their outputs after training to achieve even greater realism. These networks therefore mediate between computational geometry and artistic reasoning enabling correct contextually driven digital restoration of sculptural objects.

4. AI-Driven Sculptural Reconstruction

4.1. Feature extraction and historical pattern recognition

The analytical basis of AI-based sculpture reconstruction is feature extraction, which allows the conversion of the unstructured geometric and visual information into the meaningful expression of form, style, and craftsmanship. AI networks based on convolutional and transformer neural networks detect geometric primitives including contours and curvatures and relief patterns and symmetry relations on 3D meshes and multispectral textures. Such mined features are then mapped on stylistic and historical databases to identify unique artistic motifs, a method of carving or cultural meaning. As an example, Greco-Roman statues have rhythmic folds of drapery and proportion, whereas the artifacts of the South Asian world have elaborate iconographic detailing, which can be categorized through learned embeddings. The capability can also be extended through historical pattern recognition, which compares extracted features with corpora of digitized heritage collections of large scale. Using metric learning and unsupervised clustering, AI determines correlations between artifacts of similar time, geography, or artist, and, thus, makes it possible to properly attribute the style and put artifacts into context. The system is developed by incorporating art-historical ontologies and metadata, which improves semantic interpretation, i.e. differentiating stylistic development, regional adoption and culture.

4.2. Missing-Part Prediction Using Generative AI

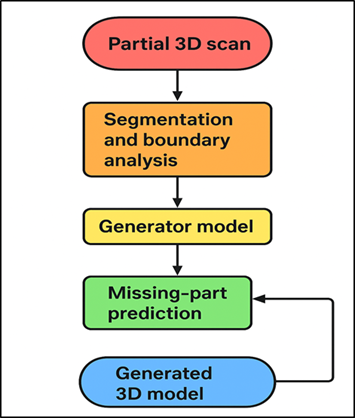

Figure 2

Figure 2 Generative AI Workflow for Missing-Part Prediction

in Sculptural Reconstruction

The generative AI can be used to restore damaged or partially unfinished sculptures by extrapolating the missing pieces of structure. In situations where scans have created gaps as a result of erosion, breakage or an incomplete preservation, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and diffusion models extrapolate the most likely continuations of form by making use of learned spatial and stylistic priors. Such models are conditioned on large 3D repositories of entire sculptures of related epochs or artistic traditions so that they can learn probabilistic associations between local geometry of the surface and overall form. Practically, the system detects the missing parts by segmenting and analyzing boundaries which are input into the generator model, which predicts the lost geometry without loss of continuity in curvature, scale, and proportion. To make sure that the generated parts are consistent with the real-world artifacts a discriminator or reconstruction loss is used. Figure 2 demonstrates that the generative AI workflow is able to foresee the missing sculptural components accurately. More sophisticated models have also included symmetry-based networks and attention modules, and balance bilateral or rotational, which is typical in sculptural design.

Notably, generative AI does not only fill blank spaces, but recreates conceivable reinterpretations in line with cultural aesthetics. Such a paradigm will turn the restoration techniques into a manual conjecture to a data-driven creative process, which will help retain the integrity and interpretative complexity of the historical sculptures.

5. Digital–Physical Integration

5.1. Hybrid reconstruction: AI + expert artisan intervention

Hybrid reconstruction is a cooperative model that combines the discursive capability of artificial intelligence with the intuitiveness of human crafts. Although AI models are highly effective in recognizing patterns, completing geometries and applying stylistic decisions, expert sculptors and conservator can offer interpretative control, where reconstructed shapes are depicted in cultural authenticity and artistic purpose. It starts with the AI-produced digital reconstructions which are based on the 3D scans, generative predictions and texture synthesis and are used as computational prototypes. A review of these outputs is subsequently done by the artisans to ensure that they correct contextual errors, sharpen anatomical or symbolic detailing and establish aesthetic harmony through historical and ethnographic information. This collaborative creativity builds a discussion that exists between machine accuracy and human intelligence. As an example, AI might be used to recreate the overall structure of a damaged statue, and the surface decoration is polished by a specialist according to the local artistic norms. This kind of integration is aimed at counteracting the biases of machine learning models trained on an incomplete or skewed data.

5.2. Additive Manufacturing and Robotic Sculpting

Additive manufacturing (AM) and robotic sculpting are essential to the translation of AI-based digital models into the real world of physical objects by means of bridging the digital precision and physical form. The additive manufacturing device methods including selective laser sintering (SLS), fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA) can be used to manufacture complex geometries layer-by-layer based on AI-generated 3D meshes. It is possible to fabricate high-fidelity reproduces with various materials including polymers and ceramics down to metal compounds with insured structural integrity and aesthetic similarity to the original sculpture. Complementary, robotic sculpture systems use the multi-axis robotic arms that have the milling or chiseling tools that can copy the complex textures, surface finished and ornamental decoration with a sub-millimeter accuracy. Hybrid processes can include printing of base structures in 3D and subsequent robotic or hand finishing in order to process an authentic surface texture.

5.3. Fidelity Assessment of Digitally Reproduced Sculptures

To preserve the integrity of heritage, it is very important to assess the validity and truthfulness of sculptures that have been reproduced by means of digital tools. Fidelity testing entails quantitative and qualitative tests which assess geometric accuracy, textural authenticity and cultural compatibility of the restored model and the original artifact. This is initiated by geometric deviation analysis in which AI based generated or synthetic replicas of a 3D scan are evaluated against standard 3D scans with reference indices like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), and Hausdorff distance.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Multicriteria Fidelity Assessment Framework for

Digitally Reproduced Sculptures

Such measures measure the alignment of the surface and consistency in the volume of the reconstructed regions. Figure 3 displays multicriteria model of measuring fidelity of reproduced sculptures digitally. In addition to geometry, other measures of texture fidelity include multispectral correlation and similarity measures of images such as Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) or Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR). Authenticity of the material is checked with the help of reflectance modeling and spectral matching that guarantee the correspondence of the restored finishes with the known material properties.

6. Applications and Future Directions

6.1. Museum replications and virtual heritage

The AI-based sculptural reproduction has transformed the museum curation and experience of virtual heritage by making it possible to produce precise, scaleable and interactive reproductions of historic artifacts. The replicas of the original objects made by 3D printing and robotic sculpting enable the museums to present the copies of extremely realistic objects that could be easily damaged or unreachable, so that they are both preserved and presented to the audience. AI-assisted reconstruction is used to guarantee that such replicas are geometrically and texturally faithful, and neural rendering is used to reproduce the material finishes of actual material, e.g. marble translucency or bronze patina. These imitations have conservation, display, and educational purposes, both to provide audiences of tactile and multisensory experience, and to preserve original works under controlled conditions. At the same time, digital heritage platforms use digital sculptures to develop spatial 3D galleries and augmented reality (AR) installations. The visitors are able to browse comprehensive models, navigate perspectives or see replicas of lost artifacts that are presented in their original contexts. Digital twins leave time excursion The condition of an artifact can be dynamically visualized over time, and conservation information is connected to popularization.

6.2. Education, Tourism, and Interactive Experiences

AI-based sculpture reproductions have become revolutionary in the field of education and cultural tourism to relate the art history tradition with the new interactive learning. Digitised and reconstructed sculptures are used in pedagogy, in art, archaeology and design courses in academia. It allows students to work with 3D models, study the development of style or recreate a situation with a restoration in virtual laboratories driven by AI. With interactive features, combining augmented and virtual reality, experiential learning makes people feel immersed in the recreated environment of a specific culture, whether it is an ancient temple or a museum archive. Through AI-based virtual guides and immersive heritage tours, the tourism industry will be more engaging to the visitor. With mobile AR applications, the tourist can see the reconstruction of the sculptures in the heritage sites and see how time or damages changed the originals. These experiences are further tailored to the individual interests or culture by AI based personalization adding depth to interpretation. Joint projects of cultural ministries, universities and technology companies are putting AI-selected exhibitions in heritage corridors and smart museums and turn tourism into a pedagogical and interactive experience.

6.3. Towards Autonomous Cultural Heritage Restoration Systems

The history of AI-enhanced sculptural reproduction indicates a direction of creating autonomous systems of cultural heritage restoration, where intelligent agents will work along the whole process of restoring, including data collection, fabrication, and participation in the process), with little or no human intervention. These systems are based on machine vision, generative modeling as well as reinforcement learning, and can autonomously detect, recreate, and assess damaged artifacts. As an example, the structural anomalies of 3D scans can be detected by adaptive algorithms, the likely historical geometries can be inferred and self-correcting feedback loops refine the reconstructions. Restoration robots have the potential to be used in the future to do finer cleaning, repairing, or additive reconstruction work in micron-level resolution, by combining robotic control and AI-based decision-making. Neural rendering systems can dynamically control patterns of material deposition in response to multispectral real-time feedback information to reproduce past surface appearance. Restoration platforms that are connected to the cloud would be able to learn continuously through federated learning using global datasets without any loss of cultural data privacy. The autonomy would also increase scalability- this would enable the decentralized restoration of artifacts in museums and heritage sites across the globe.

7. Conclusion

The merging of cultural heritage with the artificial intelligence in the reproduction of sculptures is a groundbreaking step in the maintenance, restoration, and sharing of the artistic heritage of humanity. This interdisciplinary approach combines the accuracy, scalability and contextual authenticity of data-driven intelligence with artistic skill that overcomes the shortcomings of the traditional conservation approach. The architectural frameworks of AI such as deep learning, generative and shape-completion networks, make it possible to recreate missing parts of dissolved or damaged sculptures without compromising style and historical structure. Digital heritage pipelines have been able to go into more detail and cultural depth through multimodal data acquisition by way of 3D scanning, multispectral imaging, and archival references. In addition to digital copying, the smooth digital to physical connection via additive manufacturing and robotic sculpting between virtual models and physical objects can bond the museum, conservator and educator to the heritage in previously unimaginable ways. The neural rendering is used to achieve better surface realism, and the hybrid human and AI collaboration is used to make sure that the reconstructions are artistically faithful and ethical. Not only these innovations preserve the endangered artifacts but also open new ways to access the cultural heritage democratically with the help of virtual museums, immersive learning and inclusive tourism.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Acke, L., De Vis, K., Verwulgen, S., and Verlinden, J. (2020). Survey and Literature Study to Provide Insights on the Application of 3D Technologies in Objects Conservation and Restoration. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 49, 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.12.003

Chen, Y., and García, F. L. D. B. (2022). Análisis Constructivo y Reconstrucción Digital 3D de las Ruinas del Antiguo Palacio de Verano de Pekín (Yuanmingyuan): El Pabellón de la Paz Universal (Wanfanganhe). Virtual Archaeology Review, 13, 1–16.

Cliggett, L., and Pedersen, L. (2021). The SAGE Handbook of Cultural Anthropology. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1–640.

Ghaith, K., and Hutson, J. (2024). A Qualitative Study on the Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Cultural Heritage Conservation. Metaverse, 5, 2654.

He, Y., Ma, Y. H., and Zhang, X. R. (2017). “Digital Heritage” Theory and Innovative Practice. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII‑2/W5, 335–342.

Heersmink, R. (2023). Materialised Identities: Cultural Identity, Collective Memory, and Artifacts. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 14, 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-022-00686-0

Hou, Y., Kenderdine, S., Picca, D., Egloff, M., and Adamou, A. (2022). Digitizing Intangible Cultural Heritage Embodied: State of the Art. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 15, 55. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487351

Khan, Z. (2024). AI and Cultural Heritage Preservation in India. International Journal of Cultural Studies and Social Sciences, 20, 131–138.

Leshkevich, T., and Motozhanets, A. (2022). Social Perception of Artificial Intelligence and Digitization of Cultural Heritage: Russian Context. Applied Sciences, 12, 2712. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12052712

Li, F., Gao, Y., Candeias, A. J. E. G., and Wu, Y. (2023). Virtual Restoration System for 3D Digital Cultural Relics Based on a Fuzzy Logic Algorithm. Systems, 11, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11070374

Rinaldi, A. M., Russo, C., and Tommasino, C. (2022). An Augmented Reality CBIR System Based on Multimedia Knowledge Graph and Deep Learning Techniques in Cultural Heritage. Computers, 11, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers11080172

Song, S. (2023). New Era for Dunhuang Culture Unleashed by Digital Technology. International Core Journal of Engineering, 9, 1–14.

Takimoto, H., Omori, F., and Kanagawa, A. (2021). Image Aesthetics Assessment Based on Multi-Stream CNN Architecture and Saliency Features. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 35, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2020.1765506

Xu, Z., Yang, Y., Fang, Q., Chen, W., Xu, T., Liu, J., and Wang, Z. (2024). A Comprehensive Dataset for Digital Restoration of Dunhuang Murals. Scientific Data, 11, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03068-1

Ye, J. (2022). The Application of Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Digital Humanities: Applying to Dunhuang Culture Inheritance, Development, and Innovation. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies, 4, 31–38.

Zhong, H., Wang, L., and Zhang, H. (2021). The Application of Virtual Reality Technology in the Digital Preservation of Cultural Heritage. Computer Science and Information Systems, 18, 535–551.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.