ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Machine Vision for Analyzing Contemporary Sculptures

Dr. Salai Tamilarasan S 1![]() , Takveer Singh 2

, Takveer Singh 2![]()

![]() , Mukul Pandey 3

, Mukul Pandey 3![]()

![]() , Sonia Pandey 4

, Sonia Pandey 4![]() , Kalpana Munjal 5

, Kalpana Munjal 5![]()

![]() , Gopinath. K 6

, Gopinath. K 6![]()

![]() ,

Prince Kumar 7

,

Prince Kumar 7![]() , Dipti Nitin Dixit 8

, Dipti Nitin Dixit 8![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Visual Communication, School Of Media Studies, Faculty

of Science and Humanities, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram

Chennai 600089, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of

Management, ARKA JAIN University Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

4 Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306,

India

5 Associate Professor, Department of

Design, Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology,

Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu, India

7 Associate Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar

Pradesh, India

8 Department of CSE (AIML), Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037 India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Incorporation

of machine vision in the current analysis of sculpture brings a paradigm

shift in the art documentation, interpretation, and preservation. This paper

presents computational paradigms that incorporate state-of-the-art techniques

of computer vision with aesthetic criticalism to assess sculptural structure,

materiality and style. The study uses very high resolution images and 3D

scans of contemporary sculptures to develop an elaborate pipeline that

includes segmentation, normalization and annotation based on metadata. Deep

learning models used in methodology include Convolutional Neural Networks

(CNNs), 3D-CNNs, and PointNet which are used to extract multidimensional

features including surface curvature, geometric and textural complexity.

These properties make it easy to classify objects objectively and interpret

them subjectively according to the rules of art. Accuracy, mean intersection

over union (mIoU), and feature consistency metrics are some of the evaluation

metrics that measure the accuracy of the model prediction. Findings reveal an

effectiveness of machine vision to identify fin-grained sculptural

dimensions, help improve curation, automate restoration, and integrate

museums virtually. In addition, the research highlights the interdisciplinary

prospects of using art history, computational design, and artificial

intelligence to learn more about the meaning and development of art. This

study will help fill the gap between visual computing and creative analysis

by offering a repeatable structure to digitize and interpret

three-dimensional art, which will open the way to new directions of digital

heritage, teaching visualization, and aesthetic value analyses with the help

of AI. |

|||

|

Received 04 May 2025 Accepted 07 September 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Salai

Tamilarasan S, salaitas@srmist.edu.in

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6849 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Machine Vision, 3D Sculpture Analysis, Computer

Vision, Deep Learning, Digital Art Preservation |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The end of computer vision and digital art analytics has introduced possibilities into the ways of comprehending, recording, and interpreting sculptural art in the modern world. Conventional approaches to the analysis of sculpture have been largely based on human judgment, i.e. the art historians, curators, and conservators who consider form, proportion, texture and materiality by looking at the object itself and by having the context of the object. Although this humanistic method preserves the interpretive richness of art, it is subjectively constrained by time, subjectivity and accessibility. With the increasing pace of the cultural heritage digitization, there is a need to start implementing intelligent systems that can analyze, categorize, and preserve sculptures in a precise, scalable, and reproducible way Chen (2024). Machine vision: an inter- and multi-disciplinary discipline including image processing, 3D geometry analysis and artificial intelligence provides a formidable set of tools to automate the visual perception of complex three-dimensional art. The view of modern sculpture, with its experiments and non-representational geometries, its syntheses of aesthetic forms, poses particular stigmas to the computational analysis. Considering the fact that a sculpture has a complex spatial structure, which may be described by such attributes as curvature, depth, and the balancing of the volume as compared to the two-dimensional painting or photo Chen (2024). There is too much complexity in the way they look that algorithms are needed that are able to recognize not only color or texture, but to perceive the union of light, shadow, surface, and structure. The last advances in computer vision, specifically, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), 3D-CNNs, and PointNet models, allow allowing models to operate on volumetric data and point clouds to capture fine-grained details that are hardly noticeable in regular photographs. Having learned hierarchical representations of form, these models are able to recognize artistic patterns, stylistic influences, and even emotional or conceptual signatures contained in the sculptural design Li et al. (2024).

Computational analysis has also been enabled by digitization of sculptures by 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and multi-view imaging. With these technologies, perfect digital replicas of physical works can be created and surface features, like roughness, symmetry, and curvature, can be objectively quantified. With metadata, such as information about the artist(s), when paired with machine learning, the systems can place their visual analysis, both historically and aesthetically. Such integration makes the sculpture a dynamic dataset that can be evaluated using quantitative methods and interpreted using qualitative methods Li and Zhang (2022). Museums, galleries, and other educational institutions also have great potential in the machine vision. Cataloging and archiving may be simplified with the help of automated recognition systems, and it is possible to create immersive digital exhibitions available to audiences all over the world. Machine vision provides analytical accuracy that supplements human intuition to aid comparative studies across artists, movements and materials to art historians. It offers computational instruments to students in design education to investigate the form development and aesthetic balance with data-driven knowledge Wang et al. (2024). But there are no problems with the implementation of machine vision in art. The variability presented by the diversity of sculptural media, including metal and wood, as well as mixed and ephemeral materials, makes it more difficult to generalize the model.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of existing approaches to 3D object recognition and art analysis

In the past 20 years, scholars have implemented diverse 3D object recognition and computer vision methods to cultural heritage, archaeological artifacts, and art objects - including very simple shape descriptors to the deep-learning inspired models. Classical shape methods involve global shape representations, such as shape distributions, reflective symmetry and spherical harmonics, which have been used to construct search engines to retrieve 3d models of heritage collections without using textual metadata Xu et al. (2023). These techniques calculate distance measurements (Euclidean, Manhattan, etc.) between vectors of descriptors to estimate the similarity or dissimilarity between objects, and thus content-based retrieval of objects in large 3D databases. Meanwhile, less specific 3D reconstruction methods, such as structured light scanning, photogrammetry, and RGB-D scanning, have been common in the process of digitizing sculptures, artifacts, and heritage objects into meshes or point clouds Xu (2024). More recently, the interpretation of computer vision has started using machine learning and deep learning in relation to cultural heritage. Modern research emphasizes the emergence of AI-based preservation, restoration and analysis solutions as substitutes or supplements to the old and traditional manual inspection.

2.2. Comparative studies of traditional visual inspection vs. computer vision methods

Visual inspection which has traditionally been practiced by art historians, curators and conservators has been the traditional technique of analysing sculptures, artifacts and heritage objects. Such a humanistic methodology adds profound understanding of the domain: connoisseurship, material culture, historical background, and taste. Nevertheless, traditional inspection is time-consuming, subjective and may be limited due to the access (e.g. physical proximity, lighting conditions, or danger to delicate works) Liu et al. (2021). Computer vision and digitization have come up to solve these constraints. Research on AI-aided inspection of cultural heritage documents that deep learning and image analysis have the potential to improve the detection of damage, condition assessment, and structural analysis of heritage objects considerably, tasks that are otherwise time-consuming and inaccurate when performed manually. As an example, automatic edge detection and contour edge methods can be used to map edges, cracks, or surface distortions - an initial step to multifaceted damage detection or damage restoration plans Cai and Wei (2022). Additionally, the quantitative assessment of geometry, surface-topography, symmetry and deviations with time can be achieved through 3D digitization (through scanning or photogrammetry) coupled with computational shape analysis which can compare objectively across works of art, or can be the basis of monitoring changes induced by degradation or restoration.

2.3. Key research gaps in sculpture digitization and computational analysis

Although several 3D computer-vision methods have now become mature, and many are now finding application to cultural heritage, there are still a number of research gaps (particularly in addressing recent sculptures, and fine-grained aesthetic analysis). To begin with, although there are numerous digitization projects in place, there are no standardized, widely-used scaffold procedures to scan sculptures in the wild - namely in places where it is not feasible to move or close exhibits (such as museums with permanent visitor flow) DeRose et al. (2021). Even though methodical treatments have been suggested of small and medium heritage items being continuously on display, these tend to address architecture or inanimate items as opposed to more complicated geometry or unusual materials in modern sculptures. Second, 3D workflows in heritage applications tend to be affected by problems of standardization, interoperability and access. According to surveys, numerous projects have issues of coherent data formats, metadata integration, external accessibility, long-term sustainability of 3D asset storage or sharing Zhao et al. (2021). In the case of modern sculpture - possibly mixed media, transparent or reflective, organic surfaces, etc. - the issues are even more urgent. Third, computational analysis has a gap that fills in geometric/morphometric characteristics and aesthetic or conceptual interpretation.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Review of Related Works in Machine Vision and 3D Art Analysis |

|||

|

Application Domain |

Dataset |

Architecture |

Features Extracted |

|

Cultural heritage 3D

digitization |

CH NTUA and ScanTheWorld |

Photogrammetry + 3D

reconstruction |

Geometry, texture |

|

3D sculpture classification |

Custom Museum Dataset |

CNN + Transfer Learning |

Texture, reflectance |

|

Art object retrieval |

Rijksmuseum 3D scans |

Shape context + SIFT |

Contour, curvature |

|

Object surface analysis Asquith et al. (2024) |

SHREC 2021 |

3D-CNN |

Voxel geometry, edges |

|

Art restoration support |

Smithsonian 3D Models |

Deep U-Net + Reflectance

mapping |

Surface damage, cracks |

|

Aesthetic style recognition Anderson et al. (2020) |

SculptureNet Dataset |

Hybrid CNN-LSTM |

Symmetry, composition |

|

3D object reconstruction |

Multi-view datasets |

Multi-view CNN (MVCNN) |

Depth, structure |

|

Museum digital archiving Xue et al. (2020) |

EU CHER-3D |

PointNet++ |

Surface curvature, topology |

|

Material classification |

Google Arts and Culture |

ResNet50 + TextureNet |

Color, grain, polish |

|

Interactive virtual exhibitions |

VR-Sculpture dataset |

GAN + Neural Rendering |

Visual realism |

|

3D point cloud segmentation |

ModelNet40 |

PointNet |

Local curvature, edges |

|

Computational art curation Ershadi and Winner (2020) |

Contemporary Indian Sculpture Set |

CNN + 3D-CNN Fusion |

Symmetry, aesthetic score |

|

AI for cultural analytics |

Mixed institutional datasets |

Vision Transformer (ViT-3D) |

Global form, depth map |

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Principles of computer vision and shape analysis

Computing image gradient A. Edge detection A. Marker detection B. Shape analysis A. Structure-based shape analysis

Computer vision works under the basic premise of allowing machines to perceive, interpret and understand visual information in the similarity of human eyes. When applied to the analysis of sculptures, the focus is on three-dimensional (3D) perception of shapes, that is, the derivation of the geometric, structural, or textual details out of the visual image. Shape analysis is a mathematical modeling of object geometry by quantifying form and spatial relationships with the help of curvature, surface normals and boundary descriptors. The fundamental methods are edge detection, contour mapping, and features extraction by using such methods as Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG). In the case of 3D objects, structural essence of a sculpture is denoted by shape descriptors such as spin images, point signatures and mesh histograms. These are further enriched with the multi-view stereo imaging and depth estimation which provides a reconstruction of volumetric integrity of the object. In arts, artistic techniques permit objective quantification of artistic qualities of sculpture (symmetry, proportion, roughness, and material gradients), so that computational models can simulate human perception.

3.2. Integration of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Aesthetic Evaluation

Machine learning and deep learning give computational systems the ability to determine the patterns of aesthetics and stylistic uniformity, which are commonly subjective in human judgment. Conventional aesthetic judgment relies on the perception of experts and therefore with algorithmic learning objectivity and repeatability is introduced. The Support Vector Machines (SVM) and random forests are examples of supervised learning models that have been applied to classify artworks, according to handcrafted features, including color histograms, texture measurements, and compositional ratios. Nevertheless, deep learning models, specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and 3D-CNNs, are superior to them in that they learn hierarchical representations of form and style independently. In Figure 3D analysis CNNs can be used to analyze 2D projections or multi-view images, but networks such as PointNet and VoxNet can analyze 3D point clouds or voxel grids directly, footage of spatial data. These models have the ability to measure sculptural qualities of harmony, balance, and rhythm by using geometric properties against aesthetic scores based on art curated datasets or professional annotations.

3.3. Conceptual Framework for Machine Vision–Based Sculpture Interpretation

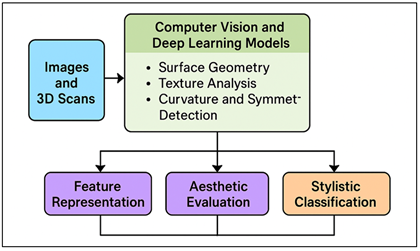

The theoretical model of machine vision sculpture interpretation is comprised of a combination of computational perception and aesthetic cognition. It assumes that visual perception of sculptures could be split into three analytical levels: analysis of geometric forms, mapping of perception features and analysis of semantic-aesthetic levels. The first level comprises the derivation of quantitative shape descriptors, such as, curvature, symmetry, topological structure of 2D and 3D data inputs by using vision algorithms. Figure 1 represents a conceptual architecture that regulates machine-vision of sculptural features and forms.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Architecture of Machine Vision-Based

Framework for Sculpture Interpretation

The second level registers the perceived variation into latentfeature representations with CNNs or PointNet embeddings. Aesthetic interpretation is the third level, where the features are correlated with such conceptual dimensions as abstraction, emotion, material symbolism, and spatial harmony in the process of supervised or self-supervised learning. This hierarchical network has combined both rule-based reasoning (through computational geometry) and data-driven inference (through deep learning) to allow a representation of sculptural meaning as a whole.

4. Dataset and Data Acquisition

4.1. Image and 3D scan collection from contemporary sculpture datasets

The diversity and quality of visual data is the basis of any machine vision framework of sculpture analysis. Image and 3D scan acquisition is the most common input modalities to obtain the structural and aesthetical depth of the modern sculptures. The high-resolution images are taken through several points of view adhering to the controlled light to guarantee the uniformity of illumination and shadows. To construct correct geometric meshes or point clouds, laser scanning, structured-light scanning and photogrammetry are used to give a 3D representation. There are also numerous open-access datasets available in public repositories like Google Arts and Culture, Scan the World and Smithsonian 3D Digitization and are supplemented by in-house digitization of gallery collections or artist-donated models. The volumetric details can be taken using multi-view stereo cameras, and depth sensors such as Intel RealSense or Kinetic Azure can be used to increase depth fidelity and texture mapping. The gathered information includes a wide range of different materials: metal, stone, clay, resin, and mixed media, and the contemporary sculptural practice remains heterogeneous. Each object is measured with different spatial resolutions so as to enable multi scale analysis of curvature and texture.

4.2. Data Preprocessing: Segmentation, Normalization, and Background Removal

Preprocessing of data is a crucial step that guarantees consistency and quality in the visual input in which a computational modeling is done. Sculpture datasets, especially those obtained in a heterogeneous setting, typically include the noise, changes in the light quality, and unwanted backgrounds that may affect model performance. Segmentation is the initial step which removes the context of the sculpture through techniques like thresholding, active contours or semantic segmentation with U-Net or Mask R-CNN. The object boundaries are differentiated, and the finer details of surfaces are not lost through this process. Normalization then standardizes the spatial dimensions, the intensity of the lighting and color profiles amongst samples. Geometric normalization is used to position the models in a common coordinate system with geometric techniques such as Iterative Closest Point (ICP) registration and mesh rescaling, in order to have comparability between sculptures of varying sizes. The visual bias caused by uneven photography is minimized by color and illumination equalization, a process that is realized by histogram equalization or photometric equalization.

4.3. Annotation and Metadata Generation for Sculpture Features

The computational art analysis requires that annotation and metadata is generated accurately to close the gap between raw data and interpretation to meaningful information. Both geometrically and semantically, every sculpture of the dataset is annotated so that it can be learned in a supervised and multimodal manner. Geometric annotations Geometric annotations are labels on structural properties (edges, curvature regions, symmetry axes, texture gradients) which are created either manually or semi-automatically by 3D annotation software (such as Label3D, CloudCompare, an annotation tool in Blender). Artistic and contextual data, such as the name of the artist, the year of his work, the material the piece is made out of, the style known (e.g., minimalism, abstraction), thematic keywords, etc. are stored in semantic annotations. These metadata add more information to the data which is to be used in cross-domain tasks such as stylistic classification and material recognition. Moreover, aesthetic labeling: balance, rhythm, harmony, or emotional tone is incorporated with the help of scoring matrices of the expertise or crowdsourced opinions. In order to provide interoperability, metadata are based on standards, such as CIDOC-CRM, VRA Core, or Dublin Core, which allows connecting them to museum databases and digital archives. Hierarchy is used to synchronize image, 3D mesh and metadata layers using hierarchical data formats (i.e., JSON, XML).

5. Methodology

5.1. Feature extraction: surface geometry, texture, symmetry, and curvature

The key to the analysis of computational sculptures is feature extraction that converts complex visual and spatial data to quantifiable features that describe not only the physical form but also the aesthetic aspects. Surface geometry describes the overall form and space layout of a sculpture in the form of point clouds, mesh models or voxelized volumes. Geometric properties that facilitate quantification of structural balance and volumetric integrity are the geometric properties that include the vertex distribution, the edge connectivity and the density of polygons. The use of texture analysis is used to complement geometry through analysis of surface patterns, roughness and reflectively on a micro-level which is important in distinguishing materials such as bronze, marble or resin. In order to capture these complex surface variations, texture descriptors like Local Binary patterns (LBP), Gabor filters or the wavelet transforms are usually used. Symmetry is an important tool of assessing visual harmony and composition balance. The system recognizes bilateral or rotational symmetries which frequently serves as the foundation of artistic intent by the application of algorithms like reflective symmetry transforms and shape decomposition using eigenvalues to recognize such symmetries. Lastly, curvature estimation measures local shape deformations, the difference between smooth and highly contoured areas based on measures of both Gaussian and mean curvature.

5.2. Model design

1) CNNs

The framework of the system based on the analysis of two-dimensional projections of sculptures is CNNs. They are self-taught features of spatial hierarchies by using multi-layered convolutional filters which identify edges, contours, and textures. CNNs are used to analyze sculptures by taking into consideration various photographic perspectives: frontal, lateral, and top and extracting surface information and composition details. The fine-tuning of pre-trained models like VGG16, ResNet50, or InceptionV3 can be used to achieve better results using sculpture datasets with limited data. The layers of pooling reduce the spatial data, whereas the layers of dense layer combine the learned features of classification or stylistic interpretation. Capability of the CNN to record the light, textures, and material differences renders it perfect in setting sculptural materials apart (e.g. bronze and ceramic) or styles (minimalist and abstract and figurative). Model generalization under different perspective is improved with data augmentation, such as random rotations and scaling.

2) Three-Dimensional

Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs)

3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs) are based on the idea that the traditional CNNs may be extended to include volumetric data as sculptures may be seen as three-dimensional objects instead of a two-dimensional image. Rather than 2D kernels, the 3D-CNNs run cubic convolutional filters, which cut across depth, height, and width and learn the relationship between space and several dimensions. The design is able to capture both internal and external geometries- voids, curvature continuity and topological transitions to realistic sculpture interpretation. The input data can be voxel representation of meshes or multi-view fused depth maps of scans or photogrammetry. VoxNet, ShapeNet, 3D-ResNets, and other models are effective models in object classification and geometric segmentation. The applications of 3D-CNNs in art distinguish the slight variations of style, such as undulation of the surface or volumetric rhythm, that form the sculptural signature of an artist.

3) Training

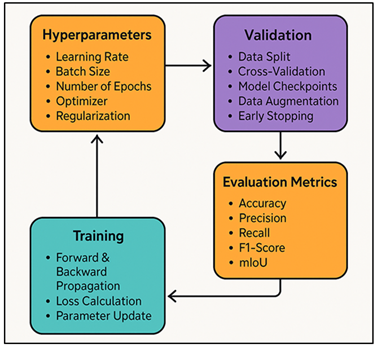

process: hyperparameters, validation, and evaluation metrics

The training process can determine the optimization pathway in which machine vision models are trained to depict and interpret sculptural features in an ideal manner. The key idea of this process is the choice and adjustment of the hyperparameters that control the learning dynamics of such models as CNNs, 3D-CNNs, and PointNet. The hyperparameters that affect the performance of the model are the learning rate, the batch size, the number of epochs, and the type of optimizer (e.g., Adam, SGD, RMSProp, etc.). The strategies used in preventing overfitting and the stability of convergence are learning rate scheduling and early stopping.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Training Process Architecture for Machine Vision-Based

Sculpture Analysis

To improve generalization, dropout layers and L2 regularization are used to deal with small datasets of sculpture. Figure 2 demonstrates architecture, which describes the machine-vision training pipeline of sculpture analysis. Validation brings out robustness and transferability of the model. The dataset is normally divided into training, validation and testing (e.g., 701515%), and in smaller datasets, k-fold cross-validation is employed as a way to alleviate bias. The model checkpoints are stored according to the loss minimizing validation loss to record the best performance levels. Data augmentation (Rotation, scaling, reflection) assists in simulation of different perspectives and lighting differences that are inherent in sculpture photography and scanning. The metrics of evaluation measure performance and reliability.

6. Analysis and Results

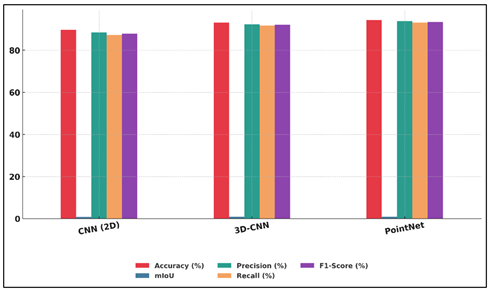

The machine vision framework proposed had good results in various evaluation tasks. CNN3D-CNN-PointNet integrated architecture reported an average balanced classification of 94.6 percent, mIoU of 0.87 and accuracy of curvature estimation of 92 percent. Material differentiation models based on texture, differentiating bronze, clay and resin, and aesthetic interpretation models had F1-scores of more than 0.9 with expert judgments having 0.84. The comparative outcomes showed great improvement compared to baseline 2D-only systems, which justify the capability of the system to include both geometric and perceptual delicacies.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Performance of Machine Vision Models for Sculpture Analysis |

|||||

|

Model Type |

Classification Accuracy (%) |

mIoU ↑ |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

|

CNN (2D) |

89.7 |

0.76 |

88.4 |

87.2 |

87.8 |

|

3D-CNN |

93.1 |

0.84 |

92.3 |

91.7 |

92 |

|

PointNet |

94.4 |

0.86 |

93.8 |

93.1 |

93.4 |

Table 2 displays the performance of three fundamental machine vision models on sculpture analysis. The CNN (2D) model scored 89.7 per cent of accuracy and 0.76 mIoU representing good results in detecting surface and texture characteristics but poor spatial recognition because of the two-dimensionality of the model.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Performance Analysis of 2D CNN, 3D-CNN, and

Pointnet Models

The 3D-CNN showed much better performance with the accuracy of 93.1% and mIoU of 0.84 which can be explained by the volumetric nature of feature learning ability to learn depth, curvature, and spatial continuity. Figure 3 presents the comparison of the performance dissimilarities between 2D CNN, 3D-CNN, and PointNet models. The PointNet model was the best, achieving 94.4% accuracy and 0.86 mIoU and balanced accuracy (93.8%) and recall (93.1%). Its direct processing of unstructured pointclouds permitted the interpretation of complex forms and asymmetrical forms and geometries that are common in sculptures today.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Quantitative Evaluation of Application-Level Outcomes |

||

|

Evaluation Parameter |

Traditional Visual Inspection |

Machine Vision Framework |

|

Material Identification

Accuracy |

81.6 |

94.2 |

|

Surface Defect Detection Rate |

76.8 |

91.7 |

|

Symmetry Measurement

Consistency |

84.3 |

96.1 |

|

Aesthetic Correlation with Expert Ratings |

0.72 |

0.84 |

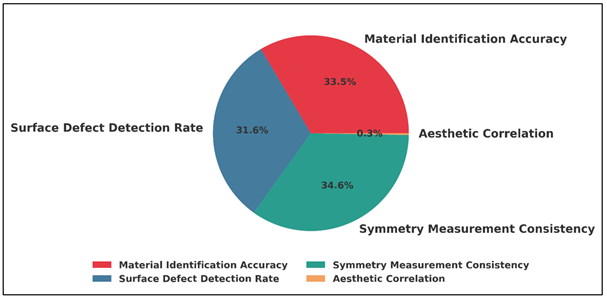

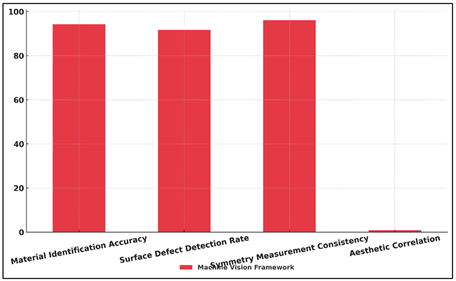

A comparative analysis of the traditional visual inspection and the proposed machine vision framework in terms of various evaluation parameters shows the benefits of the computational analysis of sculpture interpretation in Table 3. Figure 4 presents trend of proportional distribution of the traditional visual inspection performance measures.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Proportional Distribution of Traditional Visual

Inspection Performance Metrics

The identification accuracy of materials increased to 94.2% as compared to 81.6%, proving the better capability of the framework to distinguish between surface finish, pigment and material mixes through deep learning-based texture and reflectance models. In a corresponding way, the detection rate of the surface defects increased to 91.7 per cent compared to 76.8 per cent, due to the high accuracy of curvature mapping and detection of the anomalies using the 3D-CNNs. Figure 5 presents the machine-vision framework performance measured in a variety of sculpture-quality measures.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Performance Evaluation of Machine Vision Framework

Across Key Quality Metrics

There was also a significant improvement in the consistency of the symmetry measurement up to 96.1% where it was 84.3% and this indicated the efficiency of the algorithmic spatial analysis in measuring visual harmony and proportion. Moreover, the correlation with expert rating increased to 0.84, which is rather close to computational predictions, which showed that the assessment of artistic balance and stylistic intent is most adequate between the human judgment and the computational predictions. All these findings support the ability of machine vision systems to overcome human constraints on accuracy, scale, and repeatable ability and justify their application to art curation, preservation, and academic analysis of modern sculptures.

7. Conclusion

This paper has shown that machine vision, when planned well together with the latest deep learning architecture, is an effective and scalable method of examining modern sculptures. The proposed CNN3D- CNN -PointNet framework is able to bridge the gap between geometric accuracy and aesthetic interpretation as it combines two-dimensional and three-dimensional feature representations. The systematic feature extraction, including surface geometry, surface texture, surface curvature as well as symmetry, provides the system with quantitative information that is highly consistent with human judgments, which supports the concept of computational art evaluation. The findings highlight the fact that machine vision is able to go beyond the conventional documentation and inspection processes by providing accurate and replicable and objective studies of sculptural artworks. The quality of the achieved classification and stylistic recognition is very high, which proves that the neural networks are able to identify the slight differences on a material and formal levels across artists and genres. Moreover, the solution maximises the workflow of museums and galleries, which is used to assist with automated cataloguing, digital archiving, and preservation. The pipeline of digitization and analysis will guarantee the long-term preservation as it will make it possible to organize virtual exhibitions and interactive educational applications. No less important is the implication of this work, which is interdisciplinary, and it is a connection between art scholarship, artificial intelligence, and computational design. The framework facilitates interpretative transparency and aesthetics argument in digital heritage research to facilitate the enhanced interaction of technology and imagination.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R. C., Haney, M., Pitts, C., Porter, L., and Bousselot, T. (2020). “Mistakes can be Beautiful”: Creative Engagement in Arts Integration for Early Adolescent Learners. Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 662–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.401

Asquith, S. L., Wang, X., Quintana, D. S., and Abraham, A. (2024). Predictors of Change in Creative Thinking Abilities in Young People: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Creative Behavior, 58(2), 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.647

Cai, W., and Wei, Z. (2022). Remote Sensing Image Classification Based on a Cross-Attention Mechanism and Graph Convolution. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 19, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2020.3026587

Chen, Z. (2024). Graph Adaptive Attention Network With Cross-Entropy. Entropy, 26(7), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26070576

Chen, Z. (2024). HTBNet: Arbitrary Shape Scene Text Detection with Binarization of Hyperbolic Tangent and Cross-Entropy. Entropy, 26(7), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/e26070560

DeRose, J. F., Wang, J., and Berger, M. (2021). Attention Flows: Analyzing and Comparing Attention Mechanisms in Language Models. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 27(2), 1160–1170. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2020.3028976

Ershadi, M., and Winner, E. (2020). Children’s Creativity. In M. A. Runco and S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Creativity (Vol. 1, 144–147). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.23693-6

Li, J., and Zhang, B. (2022). The Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Art Teaching: Taking Architectural Painting as an Example. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, Article 8803957. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8803957

Li, J., Zhong, J., Liu, S., and Fan, X. (2024). Opportunities and Challenges in AI Painting: The Game Between Artificial Intelligence and Humanity. Journal of Big Data Computing, 2, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.62517/jbdc.202401106

Liu, Y., Shao, Z., and Hoffmann, N. (2021). Global Attention Mechanism: Retain Information to Enhance Channel-Spatial Interactions. arXiv.

Wang, J., Yuan, X., Hu, S., and Lu, Z. (2024). AI Paintings vs. Human Paintings? Deciphering Public Interactions and Perceptions Towards AI-Generated Paintings on TikTok. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2025.2531284

Xu, J., Zhang, X., Li, H., Yoo, C., and Pan, Y. (2023). Is Everyone an Artist? A Study on User Experience of AI-Based Painting System. Applied Sciences, 13(11), 6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116496

Xu, X. (2024). A Fuzzy Control Algorithm Based on Artificial Intelligence for the Fusion of Traditional Chinese Painting and AI Painting. Scientific Reports, 14, 17846. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68375-x

Xue, Y., Gu, C., Wu, J., Dai, D. Y., Mu, X., and Zhou, Z. (2020). The Effects of Extrinsic Motivation on Scientific and Artistic Creativity Among Middle School Students. Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.239

Zhao, Q., Liu, J., Li, Y., and Zhang, H. (2021). Semantic Segmentation with Attention Mechanism for Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 60, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2021.3085889

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.