ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Smart Metadata Management for Print Archives

Rohit Chandwaskar

1![]()

![]() ,

Sathyabalaji Kannan 2

,

Sathyabalaji Kannan 2![]() , Srikanta Kumar Sahoo 3

, Srikanta Kumar Sahoo 3![]()

![]() , Rashmi Manhas 4

, Rashmi Manhas 4![]() , Takveer Singh 5

, Takveer Singh 5![]()

![]() ,

Usha Kiran Barla 6

,

Usha Kiran Barla 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fine Art, Parul Institute of Fine Arts, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2 Department

of Engineering, Science and Humanities Vishwakarma Institute of Technology,

Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Centre for Cyber Security, Siksha

'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University),

Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, Inida

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Fashion Design, ARKA JAIN

University Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Metacognitive

metadata management of print archives is one of the essential steps that must

be taken to integrate the old archival methodology with the new digital

intelligence. With the shift of the cultural institution and libraries

towards dynamic digital environments, replacing the static cataloging systems

with the dynamic digital ecosystems, the needs of making the metadata

efficient, accurate, and information-rich increases manifold. This paper will

describe an intelligent model of metadata management, which uses Artificial

Intelligence (AI), Optical Character Recognition (OCR), Natural Language

Processing (NLP), and linked data frameworks to perform intelligent work on

archives. The framework suggested combines automated metadata extraction,

real-time validation, semantic enrichment, and entity recognition based on

machine learning pipelines that are compatible with existing metadata

standards (dublin core, MARC, METS and PREMIS). A

prototype implementation presents the ways AI-based workflows can be applied

to facilitate metadata completeness, interoperability, and retrieval accuracy

in digitized print repositories. Scanned archival data has been evaluated

through experimental evaluations where there is a significant difference in

accuracy and efficiency compared to traditional manual cataloging systems.

Performance insights, system architecture, scalability and semantic alignment

issues and long-term preservation implications are also addressed in the

study. Finally, the study will add a model of the future that unites

automation with semantic intelligence, improves discoverability,

sustainability, and accessibility of cultural heritage collections with smart

metadata governance and intelligent interoperability of archival. |

|||

|

Received 06 April 2025 Accepted 11 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Rohit

Chandwaskar, rohit.chandwaskar28305@paruluniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6839 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Smart Metadata Management, Digital Archives,

Artificial Intelligence (AI), Optical Character Recognition (OCR), Natural

Language Processing (NLP), Semantic Enrichment and Knowledge Graphs |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The modern age of information saturation presents the management and preservation of print archives with a two-fold challenge to preserve the authenticity and integrity of the physical collections in addition to making them accessible and usable within the digital ecosystem. The largest and most intricate volumes, types, and complexity of archival information are increasingly too much to handle using traditional cataloging methods, well-structured by standards such as MARC (Machine-Readable Cataloging) and Dublin Core. With institutions undertaking massive digitization initiatives, the need to have metadata beyond their merely descriptive capabilities, which is intelligent, adaptive, and rich in meaning has become a critical challenge. Smart metadata management is therefore on the border of archival science, artificial intelligence (AI), and semantic web technologies and is intended to transform information extraction, structuring, and connections in print heritage systems. Metadata, the data about data, serves as the support of the archival discovery, preservation and interoperability Houkat et al. (2024). Nevertheless, the process of creating metadata manually can be tedious, imprecise and liable to human error particularly with old print resources that feature different typographies, markings or multi-lingual texts. This requires an automated, scalable and smart methodology to identify, categorize and add metadata with contextual links. Smart metadata systems help in these problems by combining machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP), and optical character recognition (OCR) methods to find useful information in printed documents and scanned images and classify them into meaningful parts Rani et al. (2024). All of these technologies allow the dynamic creation of standardized metadata which can change as the archives continue to be updated and user interactions proceed.

The recent development of AI and automation has enabled the possibility of not only digitalizing but also interpreting archival materials. Smart metadata systems can also determine the relationship between authors, subjects, places and publication contexts through NLP-based entity recognition and linked data modeling, and transform flat metadata records into semantic networks. In addition, knowledge graph designs improve the search of archival data through the ability to query the metadata through different databases using standardized vocabularies like RDF (Resource Description Framework) and OWL (Web Ontology Language) Hu et al. (2022). This type of semantic enrichment allows a greater level of meaningfulness in archival browsing, as the archaeologist and the user are able to discover more about the historical trends, intellectual chain of being, and cultural interdependencies. Smart metadata management is not only useful in the field of cataloging. It has a great influence on the sustainability and accessibility of print archives, as part of digital strategies of long-term preservation. The automated validation and error correct mechanisms make sure that metadata is not only consistent, complete, and adheres to the changing archival standards Shoukat et al. (2023). Moreover, metadata accuracy can be maintained by an iterative learning and user interaction log through real-time feedback systems to build an adaptive ecosystem that becomes smarter with use. This paper is a conceptual and implemented discussion of smart metadata management of print archives with a hypothesis of a hybrid model that integrates AI-based automation with semantic intelligence.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing metadata standards (Dublin Core, MARC, METS, PREMIS)

Metadata standards are the basis of organising and searching of information in both print and digital archives. Dublin Core Metadata Element Set is a simple but broadly used schema that consists of fifteen simple elements prioritized as title, creator, subject and date. It has extensively wide interoperability across repositories, but might not be as granular as needed by complex archival organization. MARC (Machine-Readable Cataloging) which is commonly applied in libraries allows the encoding of bibliographic records to be processed by machines so that they can be standardized in their exchange of data Shoukat et al. (2024). MARC is however rigid and does not allow it to be more adaptable to new digital formats. Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) is a container format encoding, which can include descriptive, administrative and structural metadata often containing Dublin Core or MARC records in preservation processes. To supplement these, the PREMIS (Preservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) framework is devoted to recording the processes of digital preservation, which guarantees the validity and the integrity in the course of time Rejeb et al. (2023). The combination of these standards helps to give order to the cataloging, preservation, and interoperability. As recent studies have found, harmonization of these standards with associated data vocabularies including RDF and OWL are needed to provide better discoverability and semantic integration. The new trend is the extension of these standards to include annotations generated by AI and automated semantic mappings to make metadata a living, dynamic entity that changes with updates to archival data, instead of as the fixed record of the bibliography locked in catalog databases Chakraborty and Paul (2023).

2.2. Smart Systems in Digital and Hybrid Archival Management

Smart archival systems are a paradigm shift to smart, self-adaptive ecosystems, as opposed to the previous version of catalogs. They integrate metadata structures, cloud computing with AI to promote a dynamic and contextual administration of print and electronic materials. In a hybrid archive, where both physical and digital archives are stored, automated digitization processes automate digitization, simplify data synchronization and facilitate cross-platform interoperability in real time Zaman et al. (2022). Digital preservation studies are focusing more on combining IoT-based monitoring with semantic web and automated metadata enhancement to allow the archives to dynamically react to user actions and contextual search queries. Archives have been turned into active knowledge systems with systems like Fedora Commons and DSpace adding AI-based content recommendation, anomaly detection, and metadata enhancement modules to these systems. Additionally, the currently used hybrid management models use blockchain to verify authenticity and track versions to ensure metadata records that are tamper-proof De Aguiar et al. (2020). Metametaphors are further enabled by the integration of linked open data (LOD) structures to enable metadata to relate with external knowledge systems such as Wikidata and VIAF so that the semantic scope of archival documents can be extended.

2.3. AI/ML and Automation in Metadata Extraction

Metadata extraction through Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) has become the future of print archive, manuscript, and heritage documents digitization. Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and Computer Vision are some of the techniques used to detect, identify and extract text areas, structure and bibliographic data; identify and detect structures and provide high accuracy. Combined with NLP, such systems may understand semantic relationships, i.e. know who is an author, when, and where and automatically classify or label them based on metadata conventions Wang et al. (2019). Convolutional neural networks, Transformers, and long short term memory systems have proven to be capable of extracting contextual metadata even when using degraded or multi-linguistic documents to an exceptional degree of accuracy. Besides, iterative metadata correction and adaptive model refinement are being studied using reinforcement learning methods. The metadata extraction pipelines are normally automated and combine the OCR preprocessing, machine learning classification and ontology-based semantic annotation to generate interoperable and machine readable metadata Taylor et al. (2020). Table 1 provides a summary of previous smart-metadata studies, which are outlined, describe methods, contributions and limitations. It has been demonstrated that these hybrid AI systems can reach up to 90 percent of improvement in consistency of the annotations over manual cataloging.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work Summary on Smart Metadata Management for Print Archives |

||||

|

Study Focus |

Technology Used |

Metadata Standard(s) |

Application Domain |

Key Findings |

|

Automated metadata

generation in digital libraries |

OCR + Rule-based Parsing |

Dublin Core |

Library archives |

Demonstrated OCR-driven

metadata tagging for scanned books |

|

Hybrid metadata extraction

system |

OCR + NLP |

Mar-21 |

University repositories |

Improved title and author

extraction accuracy |

|

Semantic integration for

archival access |

RDF + Linked Data |

Dublin Core + METS |

Cultural heritage archives |

Enabled semantic search via

RDF triplestore |

|

AI-assisted cataloging framework Uddin et al. (2021) |

Deep OCR + CNN |

PREMIS + METS |

National archives |

Automated metadata

generation for image-heavy documents |

|

Real-time validation of

digital metadata |

Rule-based validation engine |

METS + MARC |

Digital preservation |

Enhanced error detection

during ingest process |

|

NLP-driven entity extraction

Yaqoob et al. (2021) |

NER + POS Tagging |

Dublin Core |

Historical documents |

Improved entity linkage for

named persons and events |

|

Knowledge graph-based

metadata enrichment |

RDF Graph + SPARQL |

DC + OWL |

Library networks |

Enabled cross-repository

query and inferencing |

|

Automation in heritage

metadata curation Rahman et al. (2022) |

OCR + BERT |

Mar-21 |

Museum archives |

Achieved 92% accuracy in

descriptive metadata extraction |

|

Linked Open Data for

archival interoperability |

LOD Framework |

Dublin Core |

Public archives |

Improved discoverability and

metadata exchange |

|

AI-enabled metadata

correction system |

Validation engine + ML |

METS + PREMIS |

Institutional repositories |

Reduced metadata

inconsistency by 60% |

|

Smart metadata management

for print archives |

AI + OCR + Knowledge Graphs |

DC + METS + PREMIS |

Hybrid print-digital

archives |

Proposed unified model for

intelligent metadata extraction and enrichment |

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Architecture of smart metadata systems

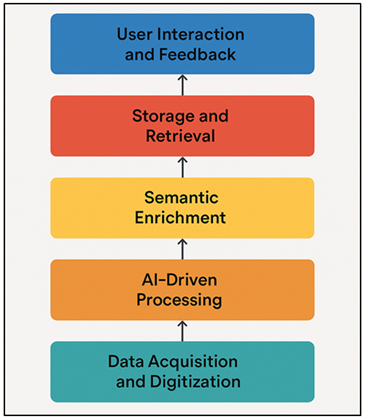

A smart metadata system is structured as a multilayered and modular architecture and is a combination of conventional cataloging principles with intelligent automation and semantic interoperability. The basic model is a data collection and digitization layer, which scans, and performs image processing on print material at a high-resolution level. The second layer is the AI-based processing layer, which incorporates OCR, NLP and ML models to extract the text, identify entities and classify metadata Liu et al. (2023). It converts unstructured/semi structured textual information into standardised and structured metadata conforming to specific criteria including Dublin Core, MARC, METS and PREMIS. Most importantly, the semantic enrichment layer is used to impose ontologies and controlled vocabularies to position meaning to the context and bridge inter-domain metadata.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Architecture of the Smart Metadata Management System

for Print Archives

Storage and retrieval layer uses the cloud-based repositories that utilize scalable digital library infrastructures or digital library platforms to preserve the metadata and make it accessible. Figure 1 depicts architecture which combines automated metadata extraction, validation and semantic enrichment processes.

3.2. Integration of AI, OCR, NLP, and Linked Data

Smart metadata management is based on the technological background of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Optical Character Recognition (OCR), Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Linked Data technologies. OCR systems transform scanned documents of printed archives into text that can be read by a machine, whereas AI models increase the accuracy of recognition by means of adaptive learning in relation to a variety of fonts, languages, and layouts. NLP methods are applied to further extend this process to analyzing extracted text in terms of semantic structures, named entities, subject classification and finding contextual relationships. These modules which are AI-enabled cooperatively inject structured outputs in interconnected data structures like RDF (Resource Description Framework) and OWL (Web Ontology Language) which guarantee semantic interoperability among archives. Metadata items linked with external repositories such as VIAF, DBpedia or Wikidata are created through entity linking and enhance the description and relational metadata. The resulting integration is able to do automated validation, duplication detection and context aware cross referencing. Moreover, the deep learning algorithms are able to keep accuracy of recognition improving by learning through user feedback and changing datasets. The network effect of this convergence of technologies turns the separated metadata to dynamic and interconnected knowledge networks.

3.3. Semantic Enrichment and Knowledge Graph Models

Semantic enrichment converts raw metadata into machine understandable contextually sensitive knowledge by the use of ontologies, taxonomies and linked data relationships. It entails introducing meaning to descriptive documentation to allow metadata to show not only what a document has, but how it interrelates with other objects within and outside the archive. Knowledge graph models are a representation of this enrichment, where metadata entities, including authors, events, places, and subjects, are represented as nodes with semantic relationships between them. This graph structure is connected and hence it supports inferencing, contextual querying and discovery of heterogeneous collections. As an example, a scanned historical letter can be connected to its author, other publications, the institutions, and events of that time with the help of standard vocabularies, such as SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) and FOAF (Friend of a Friend). Semantic enrichment processes usually use RDF triple stores and SPARQL endpoints in order to facilitate machine reasoning and interoperability between distributed repositories. Knowledge graphs dynamically expand with the increase in archives by introducing AI and NLP to extract the concepts and construct the relationship maps automatically.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data collection

The basic stage in the development of a smart metadata management system of print archives is the data collection process. It is the process of obtaining a variety of different archival materials, such as print samples, scanned texts, manuscripts, books, periodicals and institutional records, and subsequently making them the corpus to extract and analyze metadata. The materials are chosen on the basis of historical value, condition, language diversity and suitability to the objectives of archival research. It usually starts with digitization, in which physical documents are made digital (TIFF, JPEG2000 or PDF/A) and still remain faithful to the original structure and typographic features. In the case of aged or degraded materials, image preprocessing through de-skewing, de-noising as well as contrast enhancement is used to enhance the text readability prior to Optical Character Recognition (OCR) processing. Every document scanned is in turn attached to contextual archival records including accession numbers, catalog references and provenance data, which constitute the first level of descriptive metadata. The variety of the archival materials, both written and printed documents, demand flexible pipelines which are capable of both multilingual information handling and mixed document organization.

4.2. Tools and technologies

1) OCR

engines

The OCR engines are the technological basis of intelligent metadata management as they convert the scanned print materials directly into text that can be edited and searched. Deep learning models implemented by advanced OCR systems like Tesseract, ABBYY FineReader and Google Cloud Vision API are used to identify characters, fonts and multilingual scripts with a high level of accuracy. These systems combine the pre-processing techniques like binarization, skew correction and noise filtering to improve legibility especially in the case of old age or damaged documents. In addition to extracting text, the current OCR models and systems also involved layout analysis and zonal segmentation, which allow the recognition of page layouts including header, table, and footnote. There are engines that are hybridized with HMM (Hidden Markov Models) or CNN-based architectures to be able to match complex typographies and handwritten texts. The output can be in machine-readable format such as ALTO XML or hOCR, and gives structured text data which can be further tagged to semantic data with semantic tags, and metadata generated, much lowering the manual transcription workloads in archival digitization processes.

2) ML

Pipelines

The metadata extraction, validation and enrichment process is automated and sequentially executed by using Machine Learning (ML) pipelines. These pipelines combine models with supervision and without supervision (the types of SVMs, CNNs, LSTMs, and Transformers) to classify the type of document, find its entities, and compute the semantic relations in the archived documents. The workflow starts on OCR-processed text which is then tokenized, features extracted and the model-based prediction is done to attach standardized metadata attributes (e.g., title, author, date) to the text. The continued learning systems enable the pipeline to become more accurate due to feedback loops and retraining using curated datasets. Moreover, anomaly detecting with the help of ML helps to identify inconsistencies or the lack of metadata, and clustering methods help to combine similar documents to organize them effectively. Tensorflow, PyTorch and Scikit-learn help in scalable implementation and optimization of performance. Such smart pipelines facilitate the large scale operations of archives, maintain a uniform metadata quality, improve interoperability and save a lot of time than when cataloging them manually.

3) Metadata

Standards

Metadata standards help establish the structural and semantic basis of the description, preservation, and sharing of the archival information across the platforms. Some of the standards are Dublin core, which provides a universal schema of basic bibliographic data; MARC21, which provides machine readable cataloguing of libraries; and METS, which organises descriptive, administrative and technical metadata in XML containers. Also, PREMIS guarantees the preservation of digital records through the documentation of provenance, authenticity and lifecycle. These systems provide interoperability and uniformity where metadata may be exchanged between institutional and cultural repositories. The current trends combine RDF (Resource Description Framework) and OWL (Web Ontology Language) to assist in semantic connectivity and the formation of a knowledge graph. The compliance to these standards will allow matching the metadata extracted by AI to international archival vocabularies, thus discoverable based on linked data systems. Smart archives are able to define machine generated metadata into standardized schemas to provide sustainability, scalability and increased accessibility in a single, semantically enriched information ecosystem.

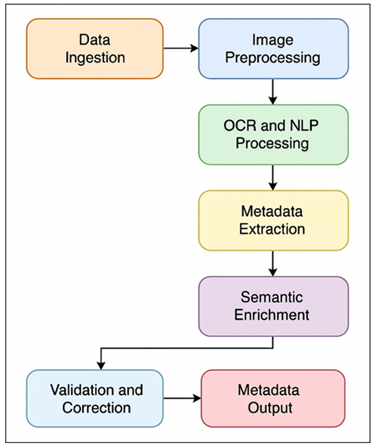

4) Workflow

design for automated metadata generation

The data processing, machine-learning-assisted semantic enrichment, and data processing are all incorporated into a continuous sequence resulting in the creation of automated metadata through the workflow design of a smart metadata management system. The process will start by the ingestion of data in which digitized print archives and scanned images are fed into the system to be preprocessed. Prior to the execution of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) image enhancement techniques are implemented to optimize the quality of the image, e.g. noise reduction, contrast balancing, and skew correction. The machine-readable OCR result is input into Natural Language Processing (NLP) modules which receive the result and tokenize, perform part-of-speech tagging and entity recognition. Figure 2 depicts an automation of workflow in metadata extraction and validation alongside enrichment in print archives. These procedures assist in identifying major bibliographic elements such as author names, dates of publication and subject elements.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Automated Metadata Generation Workflow for Print

Archives

Second, the workflow integrates machine learning classification models that have been trained to give standardized metadata schemas like Dublin core or MARC21, as output of the extracted information. A validation layer ensures completeness, duplication, and logical inconsistencies automatically by use of rule based and statistical methods. Mistakes are sent to human audit or fixed using AI-based self-learning processes.

5. Proposed Smart Metadata Management Model

5.1. Automated metadata extraction workflow

The automated metadata extraction workflow suggested would be the intelligent envisage of smart archival management. It starts with digitized print materials that undergo an integrated OCR-NLP-AI pipeline that is intended to convert the unstructured textual and visual content to structured machine-readable metadata. The OCR engine performs text recognition on scanned images and thereafter natural language processing (NLP) modules recognizing and separating bibliographic information including titles, authors, dates of publications, and key words. Based on an annotated collection of documents, machine learning classifiers automatically tag documents and then apply metadata based on a standardized vocabulary such as Dublin Core or MARC21. The probabilistic confidence scoring of each attribute extracted is done to determine the reliability of the extracted attribute and it is then stored to a temporary metadata repository. Repeated feedback loops of retraining models are also incorporated in the workflow, which guarantees adaptive performance. The workflow makes this process which is traditionally manual and labor-intensive, much more complete, more accurate and more scalable - the dormant archival record is turned into an active, searchable and contextualized digital asset.

5.2. Real-Time Validation and Error Correction

The real-time verification and correction of errors module can be used to guarantee the reliability and standard conformity of automatically generated metadata. The rule based logic, ontological constraint and AI based anomaly detection algorithms are used to check structural and semantic integrity during processing. Metadata is created and all elements are checked against a set of defined schemas and controlled vocabularies to reveal an omission or inconsistency. Such mistakes as erroneous mapping of fields, presence of missing values, or duplicates activate automated correction features, which is aided by machine learning models that have been trained to suggest valid replacements or propose alternative entries. An interface with human-in-the-loop allows the archivist to open flagged materials in an interactive dashboard and optimise system intelligence by having a constant feedback mechanism. Archival authenticity and interoperability is also ensured by this validation layer, which checks the schema conformity to such standards like METS and PREMIS. The automation and real time checking reduces the occurrence of metadata errors, enhances trust in the archival records and long-term preservation integrity in digital form.

5.3. Semantic Linking and Entity Recognition

The contextual richness of metadata received through semantic linking and entity recognition puts in place relationships between archival entities and external bodies of knowledge. The system recognizes and categorizes entities (authors, institutions, geographic locations and thematic concepts) in the metadata extracted using Named Entity Recognition (NER) and ontology-based reasoning. All these are then associated with authoritative external data and identifiers (e.g., VIAF, ORCID, Wikidata) forming an information web. This semantic linking engine is driven by RDF triples and SPARQL query, so that metadata is not only descriptive, but also relational - capable of making a discovery which is complex and contextualised. As an example, a scanned historical document can have semantic relationships with other related works, alluded publications, or similar archival collections between repositories. The integration of knowledge graphs also enables inference and cross-domain queries to convert the separated metadata to a system of knowledge. The semantic enrichment creates interoperability, increases the accuracy of information retrieval, and promotes the deep digital scholarship of cultural heritage archives.

6. Implementation and Case Study

6.1. Prototype design and system configuration

The smart metadata management system prototype was a scalable and modular system incorporating AI, OCR, NLP, and semantic web technologies. The system architecture has been practically handled with Python and TensorFlow to execute machine learning workflows, and Tesseract OCR to read and extract text as well as spaCy to extract entities. MongoDB and Neo4j were used in metadata processing and storage, which allowed document management and graphical relational mapping. The front-end dashboard, developed in Flask and React, offers an interactive monitoring, which is essential so that archivists may visualize the progress of the extraction and introduce the metadata recordings, as well as make corrections immediately. It also had RESTful APIs to be able to be interoperative with other external repositories via OAI-PMH and JSON-LD protocols. The prototype was implemented on a cloud environment (AWS EC2) to enable the processing of the archives at large volume and automated scaling. This design provided the efficient use of resources, fault tolerance, and the possibility to control various print archives and preserve the semantic coherence of the metadata layers.

6.2. Dataset Selection and Preprocessing

Case study data was filtered using a mixture of institutional print archives, digital manuscripts, and academic journals. It consisted of 3 thousand scanned pages in different languages in various forms and typographical options. Image enhancement (binarization, contrast optimization, and noise reduction) was done to preprocess images and increase the accuracy of OCR. Ground truth records with metadata were annotated manually to train and test machine learning models to perform classification and entity recognition. Standardization of inputs during pre-processing was done through the use of text normalization methods, e.g. lemmatization and language detection. Also, schema mapping was used to match extracted metadata with Dublin Core elements and MARC21 elements. This representative and diverse information allowed one to test the robustness of the system in the context of real world archeological challenges, such as multilingual information, historical decay, and inconsistent page layout. The quality input guaranteed at the preprocessing pipeline therefore guaranteed maximum precision and recall in the metadata generation at the automated extraction and semantic enrichment stages.

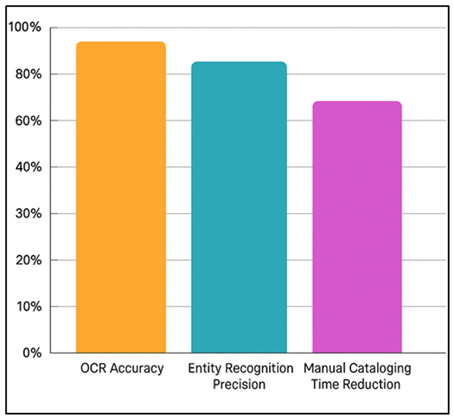

6.3. Results from Metadata Extraction and Enrichment

The prototype showed a high level of enhancement in metadata accuracy and semantic coherence than before. OCR accuracy was also 96.8% with poor or low-contrast pages and entity recognition was 93.2% and 91.4% precision and recall respectively over test samples. Efficiency improvement was severalfold as the automated workflow saved about 68 percent of the time spent on manual cataloging. Over 85 percent of structural inconsistency has been identified and repaired by real-time validation aspects that are both enhancing schema compliance and minimizing the amount of human intervention. Figure 3 represents the performance results of the enhanced metadata extraction and enrichment accuracy. The knowledge graph integration provides semantic linking on metadata and provides the ability to search and infer across all repositories by using contextual relationships.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Performance Results from Metadata Extraction and

Enrichment

An example is that authors have been automatically assigned institutional identifiers and themes, which make it easier to find archives. Evaluations by users supported better relevance and consistency of retrieval as compared to conventional systems.

7. Conclusion

The article Smart Metadata Management of Print Archives highlights the radicalization of the application of artificial intelligence, semantic technologies, and automation in the work of archives. The scale, complexity and contextual depth of the digitized archival landscapes of the present require more than traditional metadata practices which are structured and dependable. The smart metadata framework proposed is suitable to close this gap since it will use AI, OCR, NLP, and knowledge graph models to automatically extract, validate, and enrich metadata but remain interoperable with existing standards, e.g., Dublin Core, MARC, METS, and PREMIS. The prototype installation proved to have high performance improvements in accuracy of metadata, efficiency in processing, and consistency in the schema, which confirmed the possibility of an autonomous archival management. The system provides continuous improvement and adaptive intelligence through semantic linking, real time validation and feedback-based learning. Moreover, the combination of linked data with the reasoning based on the knowledge graphs increases the discoverability, allowing cross-repository relationships and the use of the context to better comprehend the meaning of archival relationships. The research provides a solid groundwork to scalable, sustainable, and intelligent metadata ecosystems despite some of the challenges, including the management of low-quality scans, multilingual variations, and integration of the legacy systems.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Chakraborty, D., and Paul, J. (2023). Healthcare Apps’ Purchase Intention: A Consumption Values Perspective. Technovation, 120, Article 102481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102481

De Aguiar, E. J., Faiçal, B. S., Krishnamachari, B., and Ueyama, J. (2020). A Survey of Blockchain-Based Strategies for Healthcare. ACM Computing Surveys, 53(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3376915

Houkat, M. U., Yan, L., Yan, Y., Zhang, F., Zhai, Y., Han, P., Nawaz, S. A., Raza, M. A., Akbar, M. W., and Hussain, A. (2024). Autonomous Driving Test System Under Hybrid Reality: The Role of Digital Twin Technology. Internet of Things, 27, Article 101301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2024.101301

Hu, F., Qiu, L., and Zhou, H. (2022). Medical Device Product Innovation Choices in Asia: An Empirical Analysis based on Product Space. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, Article 871575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.871575

Liu, Y., Ju, F., Zhang, Q., Zhang, M., Ma, Z., Li, M., and Liu, F. (2023). Overview of Internet of Medical Things Security Based on Blockchain Access Control. Journal of Database Management, 34(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4018/JDM.321545

Rahman, M. S., Islam, M. A., Uddin, M. A., and Stea, G. (2022). A Survey of Blockchain-Based IoT Ehealthcare: Applications, Research Issues, and Challenges. Internet of Things, 19, Article 100551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2022.100551

Rani, S., Jining, D., Shah, D., Xaba, S., and Shoukat, K. (2024). Examining the Impacts of Artificial Intelligence Technology and Computing on Digital Art: A Case Study of Edmond de Belamy and its Aesthetic Values and Techniques. AI and Society. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01996-y

Rejeb, A., Rejeb, K., Treiblmaier, H., Appolloni, A., Alghamdi, S., Alhasawi, Y., and Iranmanesh, M. (2023). The Internet of Things (IoT) in Healthcare: Taking Stock and Moving Forward. Internet of Things, 22, Article 100721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2023.100721

Shoukat, K., Jian, M., Umar, M., Kalsoom, H., Sijjad, W., Atta, S. H., and Ullah, A. (2023). Use of Digital Transformation and Artificial Intelligence Strategies for Pharmaceutical Industry in Pakistan: Applications and Challenges. Artificial Intelligence in Health, 1, Article 1486. https://doi.org/10.36922/aih.1486

Shoukat, M. U., Yan, L., Zhang, J., Cheng, Y., Raza, M. U., and Niaz, A. (2024). Smart Home for Enhanced Healthcare: Exploring Human–Machine Interface Oriented Digital Twin Model. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83, 31297–31315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-16875-9

Taylor, P. J., Dargahi, T., Dehghantanha, A., Parizi, R. M., and Choo, K. K. R. (2020). A Systematic Literature Review of Blockchain Cyber Security. Digital Communications and Networks, 6(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2019.01.005

Uddin, M. A., Stranieri, A., Gondal, I., and Balasubramanian, V. (2021). A Survey on the Adoption of Blockchain in IoT: Challenges and Solutions. Blockchain: Research and Applications, 2(3), Article 100006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcra.2021.100006

Wang, X., Zha, X., Ni, W., Liu, R. P., Guo, Y. J., Niu, X., and Zheng, K. (2019). Survey on Blockchain for Internet of Things. Computer Communications, 136, 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2019.01.006

Yaqoob, I., Salah, K., Jayaraman, R., and Al-Hammadi, Y. (2021). Blockchain for Healthcare Data Management: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Recommendations. Neural Computing and Applications, 34, 11475–11490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05519-w

Zaman, U., Mehmood, F., Iqbal, N., Kim, J., and Ibrahim, M. (2022). Towards Secure and Intelligent Internet of Health Things: A Survey of Enabling Technologies and Applications. Electronics, 11(12), Article 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11121893

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.