ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Intelligent Movement Tracking in Performing Arts

Debanjan Ghosh 1![]()

![]() ,

Ravi Kumar 2

,

Ravi Kumar 2![]()

![]() ,

Hareram Singh 3

,

Hareram Singh 3![]()

![]() ,

Pooja Goel 4

,

Pooja Goel 4![]() , Avinash Somatkar 5

, Avinash Somatkar 5![]() , Swarnima Singh 6

, Swarnima Singh 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and IT, Arka Jain University,

Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura, 140417, Punjab, India

3 Assistant Professor,

Department of Information Science and Engineering, Jain (Deemed-to-be

University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

4 Associate Professor,

School of Business Management, Noida International University, India

5 Department of Mechanical

Engineering, Vishwakarma Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037,

India

6 Assistant Professor,

Department of Design, Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Intelligent

movement tracking performing arts has become a paradigm shift in research,

where computer intelligence is applied to creative performance. Conventional

methods of motion analysis, most of which rely on manual observation, marker

tracking systems, or single sensory modes, are incapable of tracking the

subtleties, fluidity, and stylistic diversity of dances, theatre and

performance. The recent innovations in artificial intelligence, multimodal

sensing, and real-time analytics provide new opportunities to measure

expressive movement with an unprecedented accuracy. This paper suggests an

all-encompassing design that is based on optical cameras, inertial

measurement units, depth sensors, and wearable devices and combines them with

cutting-edge machine learning algorithms, including CNN-based pose

estimators, graph convolution networks, and transformers. The system

architecture has the focus of multimodal fusion, through which it is possible

to consider the concurrent perception of visual, inertial, acoustic, and

biomechanical signals to gain deeper insights into human movement. The

processes of live performance environments, strong annotation of expressive

and stylistic features, and deep learning architecture design based on the

dynamics of performing arts are developed as a methodological pipeline. They

have been applied to choreography analysis, automated assessment of

movement-quality, intelligent systems of teaching dance and acting, and

performance optimization using biomechanical feedback. |

|||

|

Received 08 April 2025 Accepted 13 August 2025 Published 25 December 2025 Corresponding Author Debanjan

Ghosh, debanjan.g@arkajainuniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i4s.2025.6831 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Intelligent Movement Tracking, Performing Arts

Analytics, Pose Estimation, Multimodal Fusion, Choreography Analysis |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background and significance of movement tracking in dance, theatre, and performance

Tracking the movement has been the key to the expressive, communicative and aesthetic aspects of performing arts. Movement patterns in dance portray a story, rhythm and emotion that create the essence of choreography intention. Theatrical performances are dependent on gesture, posture, spatial orientation and embodied interaction between actors to construct the meaning whereas performance art often incorporates improvisational or experimental movement that disrupts traditional analytical models. Traditionally, the recording and interpretation of movement has been achieved through manual observation, videotaping and subjective notation systems like Labanatation that were used by scholars, educators and choreographers. Even though these techniques can bring a lot of good information, they are usually imprecise, inconsistent and incapable of recording micro-motions or real-time transitions in intricate performances. Expressed demand The objective, fine-grained movement analysis has intensified due to the increasing inter-media character of performing arts (with respect to digital media, immersive environments, interactive installations, and virtual stages) Ma and Yang (2021). There is a growing need by artists and researchers alike to find out new tools that do not merely document, but provide dynamic interpretation, feedback and creative augmentation. The ability to track movement is important to study technique and the quality of performance, preserve cultural heritage, assist the reconstruction of choreographies, compare cultures, and make the process more accessible to learners with various physical capabilities Wang et al. (2025). Real-time motion understanding is used in modern creative applications, such as responsive stage systems, interactive projections, as well as AI-driven experiences of co-creation.

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Motion Analysis Techniques

Conventional motion analysis techniques, including manual video analysis, annotation-based motion analysis, and motion capture with markers, have been instrumental in the performing-arts literature though have been seen to have very few capabilities in the face of the contemporary complex creative world. Conventional analysis, by its very nature is subjective, which is based on the skill and interpretation of the observer and not objective quantifiable values. This causes the inconsistency of evaluators, inability to capture fine details, and lack of scalability (when dealing with large datasets or long sequences of performance). Video-based observation is also not good at capturing depths, rotational angles and micro-gestures which are needed in understanding expressive performance Ruivo et al. (2017). The motion capture is also more accurate through marker-based but limits natural movement because of obtrusive devices, reflective markers and controlled studio environments. These systems are very expensive and demand professionals and impractical in live performance, improvisational theatre or sensitivity in dance due to cultural reasons where freedom of the body is crucial. Moreover, conventional systems are usually interested only in the skeletal movement, and lack the information of the context like the facial expression, energy flow, rhythm synchronization, or interaction with the audience. The other significant limitation is the absence of multimodal integration of data Yang (2025). The combination of inertial, audio, biomechanical and environmental cues rarely occurs in traditional methods, and the lack of these fully represents artistic intention.

1.3. Role of AI, Sensors, and Multimodal Analytics in Redefining Performing-Arts Research

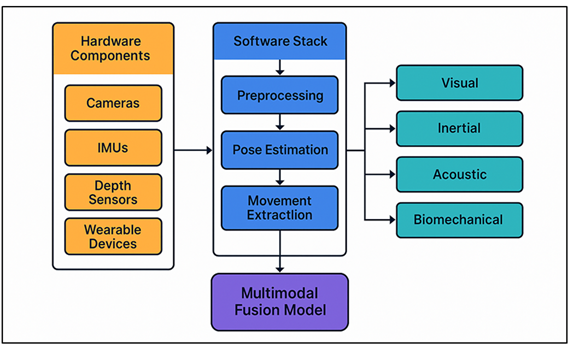

Performing-arts research is being transformed by artificial intelligence, state-of-the-art sensitization technologies, and multimodal analytics which can provide deeper, more objective and highly granular insights into human movement. Supported by convolutional neural networks, graph convolutional models, transformer-based pose estimators, AI-powered systems can fully extract skeletal landmarks, joint trajectories, and expressive cues of video with high accuracy even in complicated stage conditions. These models overcome occlusion, lighting differences, diversity of costumes, and high motion which used to be major problems to optical systems Ge (2025). They can be combined with inertial measurement units (IMUs), depth sensors, electromyography (EMG) as well as acoustic features to provide a detailed understanding of the biomechanical forces, rhythmic congruency, energy expenditure and stylistic signatures in performers. Multimodal analytics combines all that these various signals, allowing deeper interpretations of expressive movement other than skeletal coordinates allow. The AI models are able to deduce the emotional intention, the quality of movement, symmetry, fluidity, and performance efficiency dimensions, which have been hard to measure before. This creates new opportunities in studying choreography, individual training and self-feedback systems. To teachers, AI-based services offer instant testing, consist of mistakes, and personalized tutoring based on their learning preferences Jin (2024). Figure 1 depicts embedded sensors, artificial intelligence agents and movement tracking analytics. In the case of researchers, data fusion aids the analysis of cultural dance forms, embodiment of cognition and the interaction of the performers and the audience empirically.

Figure 1

Figure 1 System Architecture for Intelligent Multimodal Movement Tracking in Performing Arts

Intelligent tracking systems allow interaction phases, virtual actors, augmented-reality choreographies and AI-based tools of co-creation in the artistic world. They are also used in archiving and reconstructions of choreographic works more accurately than ever before, saving intangible cultural heritage Dogan and Kan (2020).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motion capture technologies: optical, inertial, and hybrid systems

Motion capture technologies have much developed as in the first times of the early marker-based optical systems, the advanced and efficient hybrid systems have emerged to provide realistic and high-quality motion capture in artistic settings. The optical motion capture, which has traditionally been based on reflective markers and multi-camera arrays, has high spatial resolution and detailed skeletal reconstructions, and has been a long-standing solution in biomechanics and animation research. But its reliance on not only controlled lighting, but also heavy use of calibration, and the limited ability of performers to move restrict its use in dynamic performing-arts environments Zhang and Yuan (2025). Depth camera or computer vision based markerless optical systems confront some of these limitations but still have issues with occlusion, costume variability and uncontrollable stage phenomena. The alternative to this is inertial measurement units (IMUs) which are used to measure acceleration, orientation and angular velocity without using external infrastructure. They are portable, have a low latency, and are free to move, which is why they can be used in studies of live dance, theatre, and improvisation Bu and Chen (2025). However, IMUs can easily drift, are vulnerable to sensor fusion, and cannot give results that are contextual to space without knowledge of the environment. Hybrid systems are based on the integration of optical and inertial modalities in order to take advantage of the merits of both methods. These systems counter occlusion, augment biomechanical reconstructions, and strengthen the whole system, by adding visual information to dynamics of motion. Higher popularity has accrued to hybrid methods in performing-arts studies to enable proper monitoring of multifaceted gestures, quick shifts, and movement of the ensemble members in a spatial manner Mao (2021).

2.2. AI-Driven Human Pose Estimation: CNNs, GCNs, Transformers

The field of human pose estimation has experienced an accelerated development of AI-based techniques that utilize the idea of deep learning to detect body landmarks using both 2D and 3D image data. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are the basic architecture of pose estimation, which allows making heatmaps robust, locating joints, and tracking multiple people. OpenPose and HRNet systems have proven to be very accurate in detecting skeletal keypoints across camera angle, and lighting conditions, which makes them applicable to choreographic analysis and documentation of rehearsals Xinjian (2022). Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) are a generalization of this ability, which presents the human body as a directed graph with joints forming nodes and bones as edges. The pose estimators based on GCN have strong abilities to establish time relationship, joint dependencies, and frame continuity of motion. They are especially appropriate to study rhythmic patterns, expressive traits, and stylistic shades in performance arts, where the issues of fluidity of time are so important. The latest front-end in pose estimation is transformer-based ones. Transformers are based on self-attention mechanisms that are better at extracting long-range dependencies and multi-scale motion features than CNNs or CNN-based models Svoboda et al. (2024).

2.3. Gesture and Expressive-Movement Recognition in Performing Arts

Gesture and expressive-movement recognition constitute an essential aspect of performing-arts analytics and provide the opportunity to understand the intent, emotional coloring, and style signature in art. The initial studies were devoted to rule-based systems and hand-crafted capabilities with gestures being categorized as geometric features, optical flow or trajectory patterns. These techniques were useful in dealing with simple motions, but could not cope with the fluid, many-layered, and highly changeable motions of dance and theatrical art. Expressive-movement recognition has undergone a tremendous transformation and this is attributable to deep learning Weitbrecht et al. (2023). CNNs obtain the features of the frame of the video that lie in space and recurrent models like LSTMs and GRU choose the temporal dynamics and rhythm of motion. The use of these models has led to the classification of dance styles, recognition of iconic gestures as well as an analysis of the dimensions of movement quality, including sharpness, fluidity, symmetry, and dynamic range. Recent studies use graph-based representations and transformers to learn more about the interaction among joints and expressive sequences in longer temporal periods Dellai et al. (2024). Table 1 indicates essential studies, framework, datasets and evaluation metrics overview.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary on Intelligent Movement Tracking in Performing Arts |

||||

|

Technology Used |

Sensor Type |

Movement Focus |

Domain |

Key Contribution |

|

Optical MoCap Systems |

RGB + Markers |

Full-body kinematics |

Dance |

High spatial accuracy |

|

OpenPose

(2019) |

RGB Cameras |

2D Pose Estimation |

General Performance |

Multi-person tracking |

|

HRNet (2020) |

RGB |

High-precision keypoints |

Dance/Theatre |

Strong spatial detail |

|

Kinect-Based Dance Tracking |

Depth Sensor |

Gesture Tracking |

Dance Education |

Low-cost capture |

|

GCN Motion Recognition |

RGB |

Temporal Gesture Modeling |

Theatre |

Captures joint dependencies |

|

Inertial Dance Capture Suit |

IMU Wearables |

Kinematic Motion Analysis |

Contemporary Dance |

Real-world recording freedom |

|

Transformer PoseFormer |

RGB |

3D Pose Estimation |

Multi-style Dance |

High accuracy under occlusion |

|

EMG-Based Expression Study |

EMG Wearables |

CNN + Fusion |

Muscle Activation Patterns |

Theatre Acting |

|

Rhythm–Motion Synchronization |

Audio + Video |

CNN-LSTM |

Rhythmic Movement Timing |

Dance |

|

Multimodal Fusion Tracking |

RGB + IMU |

TCN/Transformer |

Expressive Movement Recognition |

Dance/Theatre |

|

Cultural Dance Gesture Analysis |

RGB + Depth |

CNN-GRU |

Stylistic Gesture Recognition |

Classical Dance |

|

Real-Time AR Dance Feedback |

RGB |

Hybrid DL Model |

Technique Correction |

Dance Training |

|

Biomechanical Performance Analytics |

Wearables + Pressure Sensors |

Multimodal DL |

Force, Balance, Weight Transfer |

Dance/Theatre |

3. System Architecture for Intelligent Movement Tracking

3.1. Hardware components: cameras, IMUs, depth sensors, wearable devices

The moving architecture of an intelligent movement tracking system is planned to record the richness, nuance, and biomechanical complexity of human performance in the various artistic settings. The RGB cameras remain in the center and can provide continuous streams of visual data, which can display the body position, the quality of gestures, the orientation in the space, and the interaction of the performers. Multi-camera configurations can be used to provide triangulation of 3D motion reconstruction and wide-angle/panorama configurations can be used to provide large stage performance and ensemble performances. This visual information is not only supplemented by depth sensors (structured-light sensors, time-of-flight sensors) that are able to give real-time depth maps representing body contours, volumetric motion and interactions with props or stage elements, despite low-light conditions or dynamically changing lighting. IMUs help deal with difficulties in the form of occlusion or cluttered scenes by providing acceleration, angular velocity and orientation data in a direct form of the performer body. Figure 2 illustrates an integrated camera, IMU, and depth sensors that allow the achievement of an accurate motion capture. These wearable sensors are lightweight and video clipping can be done freely and they can be used in complex and fast movements typical of contemporary and classical dance.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Sensor Suite Architecture for Artistic Motion Tracking

The system is also augmented with wearable devices such as EMG patches, smart fabrics, the use of pressure-sensitive insoles, biomechanical bands, and so forth which measure muscle activity, weight distribution, joint torque, and ground-reaction forces.

3.2. Software Stack: Preprocessing, Pose Estimation, Movement Extraction

An intelligent movement tracking system software stack is a set of modular software that is created to convert raw sensor data into useful movement representations to be analyzed through art and used in real-time. Preprocessing layer has the responsibility of processing tasks like noise reduction, multimodal streams synchronization, frame alignment, IMU drift removal, and depth or acoustic signals normalization. The step is used to guarantee the integrity of data, eliminate time differences between heterogenous sensors, and prepare inputs into a high-level computation. Pose estimation is the main point of calculation. The skeletal landmarks on video or depth are detected with state-of-the-art algorithms based on CNNs, GCNs, and transformer models and used to recreate the trajectories of the joints in 2D or 3D. When the inputs are (IMU based-inputs), sensor fusion algorithms provide an estimate of kinematic states and body orientation, typically by means of extended Kalman filters or an orientation model based on deep-learning. The system can use the multi-person tracking, occlusion management, and adaptive pose refinement techniques to continue with a strong performance in the complicated stage settings. The movement extraction is based on the estimated pose sequences to extract actionable features like joint velocity, curvature, balance, rotation pattern, spatial pathways and expressive ones like fluidity or sharpness.

3.3. Multimodal Fusion Model: Visual, Inertial, Acoustic, Biomechanical Signals

A multimodal fusion model with a wide range of signals that reflect external movements and internal biomechanical events can be used to provide an in-depth and detailed perception of human movement. Facial information at both RGB and depth cameras gives skeletal key points, spatial paths, silhouettes, and volume information valuable in pose recognition. IMU measurements provide high-resolution acceleration, rotation and angular velocity information, which are useful in overcoming occlusions as well as enhancing time continuity of quick or a complicated movement. These modalities when used together contribute to strength and a high degree of reliability in tracking in any choreographic environment. Another interpretive depth is given by using acoustic cues especially in rhythmic performance. Foot strikes, breath cues, interactions between costumes and the environment which are strongly correlated with timing expressions and the intensity of movements are detected by microphones arrays or on-body acoustic sensors. Internal physical processes including muscle activity, weight transfer and balance, and force distribution are recorded as biomechanical data, either with EMG, pressure sensors or smart wearables. The fusion model combines such modalities either in an early, mid, or late stage of fusion, depending on the aim of the analytical goal.

4. Methodology

4.1. Dataset acquisition protocol for live performance environments

In live performance settings, to obtain data sets it is necessary to have a well-designed but adaptable protocol to record the dynamic, expressive, and usually uncertain artistic motion. Contrary to the controlled laboratory records, data collection in the stage should be able to absorb differences in lighting, costumes, props, spatial arrangement and improvisational behavior. The acquisition protocol is initiated by using multi-camera configuration to ensure little or no obstruction to the performance area and as much coverage as possible. The other complementary sensors include IMUs, depth cameras, environmental microphones and wearable biomechanical devices which are synchronized with a common clock system to prevent timely misalignment of modalities. Actors are informed about the location of sensors and restrictions of movement, but the point is to avoid the loss of natural art performance. The sensors should be small, non-obtrusive and should be firmly fixed so that they do not interfere with technique or choreography. The sequences of the calibrations which contain T-pose capture, a stage-depth mapping, as well as environmental noise profiling are performed at the start of every session. The recording of the same sequence of movements is done several times to record the variability in style, tempo, and the expression of emotions. The transition of lighting, the presence of an audience, the use of fogs, reflections on surfaces are also recorded to facilitate strong model training and error study.

4.2. Annotation Strategy for Expressive and Stylistic Features

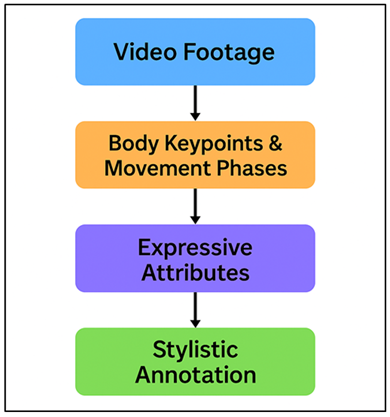

Training AI systems to interpret not just the skeletal joint paths but movement in general needs annotation of expressive and stylistic feature(s). The plan entails the multilevel annotation pipeline that is used to capture physical qualities, the expressive qualities and semantic meaning that are latent in artistic performance. On the lowest level, annotators name body keypoints, boundaries of the gestures, and stages of the movements, including initiation, peak, and resolution. Then, expressive qualities fluidity, sharpness, tension, expansion, weight, velocity, symmetry, and dynamic contrast are annotated on a continuous or discrete scale based on the known movement analysis framework as Laban Movement Analysis (LMA). The issues of stylistic annotation are movement identity, cultural specificity, and intention of choreography. In Figure 3, annotation occurs in successive steps that represent features of expressive and stylistic movements. In the case of dance genres, it can be the labeling of stylistic features as either Bharatanatyam mudras, ballet port de bras, a contemporary floorwork pattern, or theatrical gesture pattern. Emotional valence, performer-performer pattern, rhythmic alignment as well as narrative cues where movement relates to story are also captured by annotators.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Annotation Pipeline for Expressive-Movement and Style Characterization

To enhance the reliability, annotation is performed by domain experts, one of them being a choreographer, dancer, or a practice of the theatre, and is backed up by the trained assistant annotators. Programs like Cohen kappa used as inter-rater agreement protocol can be used to enhance annotation guidelines and make them less subjective.

4.3. Deep Learning Architecture for Movement Tracking

The intelligent movement tracker deep learning architecture incorporates the spatial, temporal and expressive features in multimodal neural pipeline. A pose estimator (cnn or transformer) at the visual processing stage is used to extract 2D or 3D skeletal keypoints of both RGB and depth frames. Extraction of these keypoints is the major spatial representation. Simultaneously, IMU data is fed into the LSTM layers or temporal convolutional networks and analyzed, and the fine-grained kinematic patterns are identified. Modality-specific feature specialization is guaranteed by the code of biomechanical and acoustic inputs through different sub-networks. There is a fusion mechanism used in the architecture, early, or mid-level or late fusion based on the complexity to incorporate multimodal features into a unified representation. Temporal encoders Temporal encoders are primarily based on transformers or graph convolutional networks (GCNs) that capture joint dependency and expressive movement relationships between time. With these layers, the system is able to detect style signatures, segment choreography, categorize gestures as well as the quality of movement using learned temporal dynamics.

5. Applications in Performing Arts

5.1. Choreography analysis and movement quality assessment

Smart tracking movement is an effective instrument in the analysis of choreography and evaluation of the quality of the movements more than ever before. Recording skeletal paths, joint angles, time structures, and space dynamics, AI-based systems allow visualizing and comparing choreographic elements of dancers, rehearsals, and even style differences in details. Motifs, pathways, pattern of symmetry, and relational spacing are some of the aspects that choreographers can study between performers and facilitate both creative exploration and reconstruction of intricate sequences. The rhythm consistency, the length of the phrases, and the synchronization of the ensemble works are measured with the help of temporal analytics, which are necessary to tune the artistic coherence. The quality of movement is assessed based on multimodal data; visual, inertial, and biomechanical data to provide a measure of the expression properties: fluidity, sharpness, weight transfer, control, dynamic contrast. Such objective measures are used to supplement subjective traditional evaluation in order to make the performers aware of the minor inefficiencies or deviations when performing the choreography as intended.

5.2. Intelligent Tutoring Systems for Dance and Acting Training

The intelligent tutoring systems based on AI change the training in dance and acting by providing students with individual real-time feedback on the needs of the learning process. These systems match the movements of the learners with the expert models and determine differences in posture, timing, coordination, and delivery of expressiveness. The tutoring platform provides real-time feedback that takes the form of visual overlays, corrective cues, rhythm alignment indicators, and biomechanical suggestions, which are produced by using multimodal sensing and deep-learning analytics. This helps learners to perfect technique without necessarily having to be under the supervision of an instructor. In the case of dance training, the system measures alignment, balance, accuracy of the turns, accuracy of the footwork, and the indication of style belonging to particular genres like ballet, contemporary, or Indian classical dance. In acting, the platform evaluates the clarity of gestures, expression of emotions, presence on the stage, and physical narratives so that the performers may learn how the embodied actions affect the perception of the audience. This tutoring system is adjusted to the learning pace, with progressive challenge and strengthening through repetition, as well as specific correctional exercises depending on the performance history of the learner.

6. Results and Discussion

The suggested intelligent movement tracking system proved a great advancement in the accuracy of poses, expressive-movement recognition, as well as multimodal synchronization in various dance and theatre conditions. Visual-inertial fusion eliminated the errors associated with occlusions whereas transformer-based temporal modeling helped in improving the continuity of gestures and style categorization. Biomechanical inputs also enhanced quality assessment by recording internal dynamics that the optical systems usually fail to record. The dancers and actor user studies mentioned in the article said that the interpretive clarity, more actionable feedback and better rehearsal efficiency existed. The quantitative analysis revealed a higher tracking accuracy, temporal transitions were more natural and consensus with expert annotations was higher. On the whole, the findings prove that AI-based multimodal tracking is a significant contributor to the analytical level and the level of creativity in research in the performing arts.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Evaluation of Tracking Accuracy and Expressive-Movement Recognition |

|||

|

Metric

/ Model |

CNN-Based

Tracking |

GCN

Temporal Model |

Transformer

Fusion Model |

|

2D Pose Accuracy (%) |

91.4 |

93.8 |

96.2 |

|

3D Pose Accuracy (%) |

88.7 |

92.1 |

95.4 |

|

Occlusion Robustness (%) |

72.5 |

81.3 |

89.7 |

|

Gesture Classification

Accuracy (%) |

84.6 |

88.9 |

94.1 |

|

Expressive Quality

Recognition (%) |

79.2 |

85.7 |

92.3 |

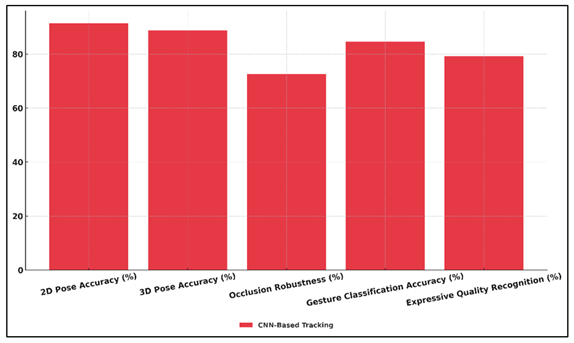

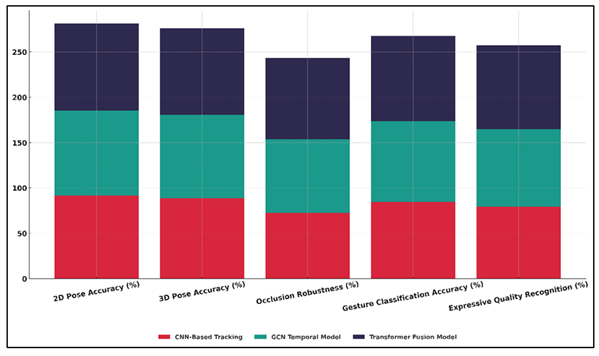

Table 2 is a quantitative comparison of three models, viz. CNN-Based Tracking, GCN Temporal Modeling, and the Transformer Fusion Model, on five fundamental metrics used to analyze performing-arts movements. CNN model has 91.4 2D pose accuracy and 88.7 3D pose accuracy with a good baseline but less effective in under occlusions that are reflected in its less robustness score of 72.5. Figure 4 demonstrates accuracy, precision, and robustness values of CNN-based tracking.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Performance Metrics of CNN-Based Movement Tracking Model

The classification of gestures (84.6%), as well as expressive-quality recognition (79.2%), demonstrates the moderate performance in space and poorer performance in time. The GCN Temporal Model is far more effective than the CNN on all measures with 93.8% 2D and 92.1% 3D pose accuracy. Figure 5 Compared multidimensional metrics in tracking models on a stacked base. Its occlusion strength goes up to 81.3, with the help of graph-based modelling of joint dependencies.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Model-Wise Stacked Visualization of Multidimensional Movement Tracking Metrics

The classification of gestures increases to 88.9, and the recognition of the expressiveness levels reaches 85.7, which proves the usefulness of time reasoning to interpret the style, emotion, and continuity of movement. Transformer Fusion Model gives the best performance in all categories. It has 96.2 per cent 2D and 95.4 per cent 3D pose accuracy which means it is spatially fidelitic.

7. Conclusion

Smart tracking of movement is a revolutionary development in the convergence of technology and performing arts that can be used to gain a better and more objective insight into movements of the human body. This paper showed that combining optical cameras, IMUs, depth cameras, and wearable biomechanical tools with AI-powered pose estimation and multimodal fusion are very relevant in terms of capturing, interpreting, and assessing the performance movement in the actual artistic setting. The subjectivity of traditional approaches and the inability to sense the image are substituted by the system that is able to identify subtle stylistic indicators, emotional signals and biomechanical dynamics that define the art of dance and theatre. The suggested framework enhances the study of choreography, promotes intelligent tutoring, and aids the optimization of biomechanics with the help of instant feedback and motion analytics. The multimodal architecture presents a comprehensive view of performer collective behavior by integrating visual, inertial, acoustic and physical signals and goes way beyond skeletal tracking. This allows better quality measurement, accurate gesture coding, and valuable information on the performance intention, timing, as well as expressiveness. Performance assessments show that it performs well in diverse styles, in diverse lighting and on diverse staging. Notably, the system relates to artistic and pedagogical requirements because the feedback provided by the system is interpretable and context-relevant, as opposed to the technical report. This alignment can be useful to professionals as well as educators, cultural researchers, and interactive media designers.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bu, Z. H., and Chen, Y. H. (2025). Cultural Value and Development Strategies of Tai Chi. Wushu Research, 10, 17–19.

Dellai, J., Gilles, M. A., Remy, O., Claudon, L., and Dietrich, G. (2024). Development and Evaluation of a Hybrid Measurement System. Sensors, 24, 2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24082543

Dogan, E., and Kan, M. H. (2020). Bringing Heritage Sites to Life for Visitors: Towards A Conceptual Framework for Immersive Experience. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 8, 76–99. https://doi.org/10.30519/ahtr.630783

Ge, Y. (2025). Localization Protection and Inheritance of Art-Related

Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Digital Era. Hunan Social Sciences, 03, 166–172.

Jin, Z. (2024). Rehabilitation Product Design for the Elderly Based on Tianjin Regional Culture. Tomorrow Fashion, 08, 97–99.

Ma, X., and Yang, J. (2021). Development of the Interactive Rehabilitation Game System for Children with Autism Based on game psychology. Mobile Information Systems, 2021, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6020208

Mao, R. (2021). The Design on Dance Teaching Mode of Personalized and Diversified in the Context of Internet. E3S Web of Conferences, 25, 03059. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125103059

Ruivo, J. M. A. D. S., Karim, K., O’Shea, R., Oliveira, R. C. S., Keary, L., O’Brien, C., and Gormley, J. P. (2017). In-Class Active Video Game Supplementation and Adherence to Cardiac Rehabilitation. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 37, 274–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000224

Svoboda, I., Bon, I., Rupčić, T., Cigrovski, V., and Đurković, T. (2024). Defining the Quantitative Criteria for Two Basketball Shooting Techniques. Applied Sciences, 14, 4460. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114460

Wang, S., Liu, Y., Mei, X., and Li, J. (2025). Gamified Digital Therapy for Reducing Perioperative Anxiety in Children: Exploring Multi-Sensory Interactive Experience. Entertainment Computing, 54, 100962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2025.100962

Weitbrecht, M., Holzgreve, F., and Fraeulin, L. (2023). Ergonomic Risk Assessment of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons—RULA applied to Objective Kinematic Data. Human Factors, 65, 1655–1673. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208211053073

Xinjian, W. (2022). An Empirical Study of Parameters in Different Distance Standing Shots. Journal of King Saud University – Science, 34, 102316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102316

Yang, F. (2025). Practical Exploration of Applying Traditional Folk Children’s Games in the Rehabilitation

of Children With Autism. Modern Special Education,

7, 64–66.

Zhang, J. G., and Yuan, Y. D. (2025). Exploring the Path of Tai Chi Practice in Promoting Harmonious Coexistence Between Humans and Nature. Wushu Research, 10, 38–41.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.