ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Management of AI-Generated Music Intellectual Property

Sunil Thakur 1![]() , Sidhant Das 2

, Sidhant Das 2![]()

![]() , Harsh Tomer 3

, Harsh Tomer 3![]()

![]() , Baisakhi Debnath 4

, Baisakhi Debnath 4![]()

![]() , Prabhjot Kaur 5

, Prabhjot Kaur 5![]()

![]() , Bineet Singh 6

, Bineet Singh 6![]() , Shweta Ishwar Gadave 7

, Shweta Ishwar Gadave 7![]()

1 Professor,

School of Engineering, and Technology, Noida, International, University, 203201,

India

2 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication,

Vivekananda Global University, Jaipur, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies, JAIN

(Deemed-to-be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

6 School of Legal Studies, CGC University, Mohali-140307, Punjab, India

7 Department of Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The recent

dramatic improvement of artificial intelligence (AI) in creative fields has

transformed the production of music, raising complicated issues of

intellectual property (IP) rights. In this paper, the author discusses the

legal and ethical issues surrounding the management of AI-generated music in

the current legal context. It starts by describing the concept of

AI-generated music and the technology of deep-learning and neural network

that makes this kind of autonomous composition possible. An analysis of human

and AI publications shows that the basic foundations of creativity, intent,

and originality, the core criteria of the IP law, are different. This paper

is a critical analysis of the existing copyright regimes, pointing out the

fact that they are ineffective in assigning ownership and authorship to the

non human creators. It explores the issue of whether rights ought to belong

to the developer, the user or is it unprotected under the existing current

doctrine. The interpretation of AI authorship and ownership in courts of

various jurisdictions by legal precedents is examined, and the consideration

of ethical issues of creative attribution is presented. In addition, the

paper examines the systems of licensing and shared rights ownership of AI generated

content, as well as the necessity to develop reasonable structures that would

equitably allocate royalties. Examples of major legal cases provided insights

into how this can be applied in practice and new trends in resolving

disputes. Lastly, the study assesses policy and regulatory reactions in the

international organizations including WIPO, EU, and U.S. agencies giving

suggestions of adapting models that consider both innovation and protection

of creative rights. By doing this thorough investigation, the paper supports

the idea of a balanced global policy that will ensure the ability to adapt to

technological changes and preserve artistic integrity and economic justice

through AI-generated music. |

|||

|

Received 26 February 2025 Accepted 24 June 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sunil

Thakur, sunil.thakur@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6799 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Music, Intellectual Property,

Authorship, Copyright Law, Policy Frameworks |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) as a creative partner and, to a larger extent, as an independent composer has completely transformed the environment of the music industry in the world. Previously existing in the domain of human invention, music composition has now become a hybrid field in which algorithms, neural networks and machine learning systems are capable of creating a rich, emotionally expressive and commercially viable music. Such AI-powered compositions question the established concept of creativity, originality, and ownership, and cast their deepest doubt on the relevance of the current intellectual property (IP) regulations to non-human authors and creators. With the continuous development of AI technologies like the MuseNet, Magenta, and AIVA (Artificial Intelligence Virtual Artist) of the OpenAI, Google, and AIVA companies, the frontier between human and machine authorship is becoming more and more blurred, so the system of assigning and protecting intellectual property rights needs to be reconsidered critically. The traditional IP model was created at the time when authorship was associated with human creativity- where a specific writer or a composer was assumed to have will, originality, and emotionality Fchar et al. (2022). The copyright legislation that is an anchor of IP protection of music works is based on the concept of human agency. It protects the moral and economic rights of the creator so that individuals who dedicate intellectual and creative efforts to producing original works receive their reward and acknowledgement.

Nevertheless, the emergence of AI music interferes with this central idea. When an algorithm is involved in writing a symphony, creating a pop song, or creating background music in a media application, the question is, who is the owner of the rights? Is it the user who provided the inputs, is it the programmer who made the algorithm or could it be that no one can say that they made it in the conventional meaning? This uncertainty poses a complex issue to the regulators, artists, developers and policymakers Messingschlager and Appel (2023). The existing copyright regulations in many jurisdictions such as the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, fail to endure AI as a creative force. Although certain jurisdictions, including the UK, have tried to resolve this problem by coming up with provisions that acknowledge the person who makes the arrangements necessary to the creation as an author of computer-generated work, such systems are still controversial and conflicting across the world. More so, the almost instant commercialization of AI-composed music (advertising, film creation, video games, digital streaming and so on) has only aggravated the necessity to have a legal framework that promotes fair-pay, proper crediting and accurate rights management Williams et al. (2020). The legal issues are not the only problem as the ethical aspects of AI creativity complicated the issue further. Music being expressive art form has been linked to human emotion, intent and culture.

2. Understanding AI-Generated Music

2.1. Definition and characteristics of AI-generated music

AI-generated music Music produced by artificial intelligence systems with the ability to analyze, compose, and produce sound is known as AI-generated music. As opposed to conventional digital products in which all creative actions are performed by the human factor, AI music-generating algorithms, especially machine learning, deep learning, and neural networks, identify patterns in a human-created music and produce a new piece of music that mimics human creativity.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Representing the Key Characteristics of AI-Generated

Music

These systems are able to create melodies, harmonies, rhythms and even lyrics, modifying stylistic delicacies of different genres of music or particular artists. Figure 1 reveals the main features that outline the idea of structure, style, and creativity in AI-generated music. The main feature of the music AI-generated is its data-driven creativity. The AI models are trained on enormous amounts of musical compositions, and they get to learn the interdependence between the pitch, tempo, structure, and emotional tone Schneider et al. (2023). When trained, these systems are capable of creating brand new pieces without any direct human instruction, or may be used to work in cooperation with musicians to improve creative procedures. This ability to produce music is what allows AI music to be differentiated among the simple algorithmic or rule-based music of the past. In addition, the AI-generated music tends to have high efficiency, indefinite scalability, and versatility in styles. It is replicable within a short period of time to be used in movie music, video games, adverts, or therapy Ning et al. (2025).

2.2. Key technologies and models

2.2.1. Deep learning

Deep learning is a branch of machine learning which is a key element in the development of AI generated music. It consists of the application of multi-layers of neural networks that are able to learn and derive intricate patterns with massive amounts of music pieces. Deep learning models are able to discover more complex features like rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, and even emotional tone, which are vital to creating coherent and pleasing music, owing to such a hierarchical learning process Yu et al. (2024). Deep learning AI music systems use large datasets of existing music of any genre and learn how to associate notes, scales and structures. After training, such models will be able to automatically produce new compositions resembling a particular style or a combination of several inspirations. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformers, among others, are also among the most prominent architectures that are highly effective in addressing the sequentiality of the music, with each note or chord being conditioned by the previous one Marquez-Garcia et al. (2022) Deep-learning can also be used to improvise in real-time and compose adaptively, allowing AI systems to collaborate with human musicians.

2.2.2. Neural Networks

Most AIs based on neural networks are the structural foundation of music generation. Following the operation of the human brain, neural networks are made up of interrelationships of layers of simulated neurons, which transfer and process information. Individual layers scan a particular musical property, e.g. pitch, tempo or harmonic progression, and aggregates the results together to produce coherent compositions Eftychios et al. (2021). Applied to music generation, neural networks are good at learning temporal relationships and allow the system to generate the next note, chord or rhythmic pattern on the basis of the elements before it. Neural network architectures have specific applications: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be applied to the audio signal and sound synthesis, whereas Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their sub-type, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are used in the analysis of time-series data, and thus they are suitable to be applied to melody generation Tang et al. (2021).

2.3. Comparison between human-made and AI-generated compositions

The difference between the compositions created by humans and those created by the AI is mainly the origin of creativity, depth, and purpose. Music made by human beings is the result of conscious artistic expressiveness - influenced by emotion and culture, intuition and experience. It usually reflects individual stories, social backgrounds and philosophical considerations, and enables the audiences to relate themselves to the will of the producer. Human composers see and use sound as a source of inspiration and technical harmony, as well as emotional appeal, spontaneity and narrative Chomiak et al. (2019) AI-generated compositions, in contrast, are based on algorithms that feed on large datasets of existing music to imitate or introduce novel musical forms. These systems are good at pattern recognition, creating melodies, and creating harmonically coherent works of unprecedented speed and magnitude. But AI does not have any real emotional consciousness, it does not feel or wants to create. Rather, it predicts and aligns musical aspects statistically and imitates human creativity Wittwer et al. (2020). Table 1 contrasts the studies that deal with the intellectual-property management issues related to AI-generated music. Although this can end up producing technically impressive pieces, critics claim that such works cannot have the ethos, human fallibility and emotional spontaneity of human art.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Analysis of Related Works on the Management of AI-Generated Music Intellectual Property |

||||

|

Focus / Scope |

Jurisdiction(s) |

Impact on IP Management |

Advantages |

Gaps |

|

Exploratory framework on

copyright and AI-music Gonzalez-Hoelling et al. (2021) |

Global (legal review) |

Provides structured view for

policymakers and rights-holders |

Helps identify driving and

dependent factors; supports strategic planning |

Doesn’t resolve authorship;

static snapshot |

|

Legal analysis of AI-music and ownership |

Global, incl. India |

Alerts to legal uncertainty; promotes reform |

Highlights data and algorithm ownership issues |

Limited empirical data; mostly doctrinal |

|

Principles, priorities and

practicalities of generative AI and copyright Grau-Sánchez et al. (2020) |

US/EU |

Supports judicial and

regulatory interpretation |

Offers framework for novelty

and originality assessment |

Doesn’t propose full

legislative solution |

|

Broad digital-content view: music, art, literature |

India + international |

Raises awareness in emerging markets |

Cross-jurisdictional comparison |

Depth of music-specific issues limited |

|

Case study of a generative

music platform (Suno) and ethics Ruth and Müllensiefen (2021) |

US |

Adds ethical dimension to IP

law discourse |

Proposes “likeness

thresholds”, metadata tagging |

Case study only; foresight

rather than proven outcomes |

|

Economic and technical solutions for rights/royalties

in AI-music |

Global (tech/legal) |

Bridging tech and law; supports equitable remuneration |

Integrates data attribution methods |

Implementation complexity; early stage |

|

Technical model for

attribution and provenance in AI-music Wei et al. (2022) |

Global (research) |

Advances traceability,

rights-management |

Offers practical

infrastructure for rights attribution |

Research prototype; industry

adoption pending |

|

Training-data attribution in generative music models |

Global (ML research) |

Helps rights-holders claim credit; supports

transparency |

Advances fairness and accountability in AI-music |

Technical focus; legal/regulatory mapping still needed |

|

Metrics for detecting

replication/plagiarism in AI-music |

Global research |

Alerts to infringement risk;

supports enforcement |

Provides measurement tool

for similarity/replication |

Doesn’t cover full

business/licensing context |

|

Industry association viewpoint Wu (2024) |

EU/UK/global |

Influences policy and industry practice |

Early roadmap of industry concerns |

Position paper, not empirical research |

3. Intellectual Property Frameworks

3.1. Overview of current IP laws in creative industries

The intellectual property (IP) laws provide the basis through which creativity and innovation in different spheres of art and technology is safeguarded. IP rights are used in creative fields to acknowledge authorship, guarantee economic gain, and avoid copyright infringement in creative practices like music, film, literature, and visual arts. Copyright is the most important element of IP in arts, protecting what is termed as original works of authorship which are fixed in a tangible form such as music compositions and sound recordings. Conventions like the Berne Convention (1886) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) are international conventions that provide a minimum standard of copyright protection and recognition of the work by the member states. These models are complemented by the national copyright laws such as the U.S. copyright act (1976) and the European union copyrights directive (2001/29/EC), which give writers the exclusive right to reproduce, give out, perform, and transform their works.

3.2. Copyright Principles Relevant to Musical Works

The copyright law secures the musical works by allowing the artists to get full access to their compositions and recordings. There are two layers of protection: one (musical composition) of protection of musical composition(melody, harmony, rhythm and lyrics) and the other (sound recording) of protection of the actual performance or recording. These rights enable the creators to regulate the reproduction, distribution, adaptation and performance of their works to ensure that they can earn economic and moral dividends of their creative work. One of the major principles of copyright is originality the minimum level of creativity and the independent human effort of a work should have been achieved. Such a principle is supported by legal principles in various jurisdictions. The Figure 2 shows some of the relevant copyright principles in the ownership and protection of musical works. An example is the U.S. copyright office which requires the registration be done by human authorship whereas European law focuses on individual intellectual creation.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Illustrating Copyright Principles Relevant to Musical

Works

Also, moral rights like the right to attribution and integrity defend the personal relationship between the artist and the work of art. In the musical work context, copyright safeguards composers, lyricists and performers by providing them with royalties and licensing. The advent of AI however is a challenge to this structure. The traditional standard of originality or authorship can not be applied to the work of an AI system since it is not conscious or intentional. It poses complicated legal concerns regarding the possibility of AI-generated compositions coming under protection and, in that case, to whom the protection is to be granted the programmer, user, or none.

3.3. Gaps in Existing IP Frameworks for AI-Generated Content

The existing intellectual property frameworks are very weak in relation to AI-generated content, which is mainly because their definitions of authorship and creativity are based on human-oriented notions. The conventional IP systems assume that there is a creator who is a natural individual with the ability to make intention, originality and moral responsibility. As an autonomous algorithmic system, AI fails to fit these requirements, putting its outputs in a legal gray zone. Authorship and ownership is one of the major gaps. No rights are legally ascribed to AI, so who should be the author of the program? It is not yet determined, whether it should be the programmer, dataset provider, or the end-user. Various jurisdictions have taken quite different positions, some such as the U.K. giving the authorship to the individual who made the arrangements that were required to create it, and others, such as the U.S., declining to offer protection at all to the non-human work. The other deficiency is originality and fixation. Artificial intelligence generated works tend to combine or imitate the design of already existing copyrighted works, making it difficult to determine originality and possible infringement. Moreover, the non-legal status of AI outputs does not help in commercializing the outputs because they can be not only unprotected but also in the status of the property of the masses. Lastly, the international level has a policy vacuum. Organizations like WIPO and UNESCO have failed to come up with coordinated guidelines on AI generated creativity and have thus led to a divided interpretation of the law. To close these loopholes, the solution will involve innovations in legislation that would strike a balance between incentives to innovate and fair attribution and protection.

4. Authorship and Ownership Issues

4.1. Determining authorship: human vs. machine vs. developer

One of the most difficult and controversial aspects in the modern intellectual property law is establishing authorship in AI-composed music. Historically, the creative expression, originality, and intent are the contribution of the author of a musical (work). But in the case of the music written independently by the artificial intelligence, the problem is that it is difficult to refer to this creative agent. The question is - should it be considered the authorship of the human programmer who created the algorithm, or the user who gives its input or parameters or the AI system itself creating the final composition? AI systems have not become the legal persons in most jurisdictions, and can therefore not assert authorship or ownership. This changes the emphasis on human actors of the creative process. The generative model could be attributed to the efforts of programmers, and the users who communicate with and direct the system could be considered as collaborative. In certain jurisdictions including the UK copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the author is described as a person by whom the arrangements required to bring about the work are made.

4.2. Legal Precedents and Interpretations in Various Jurisdictions

Different jurisdictions have different laws that regard AI as the author of copyrighted content, or the owner of that work, depending on the culture and policy approach of the jurisdiction. The Copyright Office in the United States clearly insists on the human authorship in order to be registered, and claims the registration of a work produced by a machine or a mechanical process without human intervention are not recognized. The 2023 case Thaler v. This human authorship requirement was supported by Perlmutter, in which a U.S. court refused to copyright an AI-generated piece of art made by the Creativity Machine of Stephen Thaler. The United Kingdom is more permissive. Section 9(3) of the Copyright, Designs and Patent acts of 1988 states that the authorship of works generated by computers be assigned to the individual by whom the arrangements required to create the work are made. It is a practical decision that acknowledges to some extent AI-assisted creativity but does not go as far as to grant rights to the AI. The European Union copyright law focuses on the idea of the intellectual creation meaning, which suggests that it takes a human agency. The Court of Justice of the EU has made it a point to decide that protection must be provided with individual contribution. In the meantime, the Asia region, including Japan and South Korea, is actively considering the policy reforms to determine ownership of AI-generated content, and Japan is contemplating being able to flexibly license AI outputs. Those different precedents bring out a disjointed world.

4.3. Ethical Considerations in Credit Attribution

Besides legal considerations, such a matter as authorship of AI-created music creates some deep ethical concerns in terms of creative acknowledgment and justice. Ethical credit attribution is not only about the owner of the work but the one who should be given credit on the creation of the work. Because AI is not conscious, willful, or capable of any emotional state, attributing authorship to machines creates issues with the traditional ideas about creativity and responsibility. However, one should not disregard the efforts of programmers, data curators and users who design, train and direct these intelligent systems. One of the ethical dilemmas is transparency, the listeners and stakeholders in the industry should be told whether a composition is man-made, it is artificially created by AI, or it is a collaboration. The secretive use of AI may lead to the misinformed expansion of viewers and undermine human creativity. On the other hand, the excessiveness of the role of AI can be detrimental to human input particularly where algorithms are running within human-set parameters.

5. Rights Management and Licensing

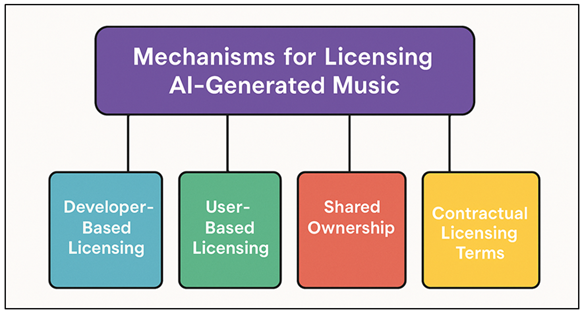

5.1. Mechanisms for licensing AI-generated music

AI-generated music is a new challenge in terms of licensing since the conventional licensing model is built around human-generated music. Simply, licensing is the identification of the way a musical work can be utilized, allocated, or commercialized so that right owners are compensated accordingly. In the case of AI-generated musical work, this process is made more difficult because there is no legally recognized author, since a variety of stakeholders may own such a piece: the programmer, the user, the data source, or the platform where the AI is deployed. In response to this, new models suggest the adoption of flexible licensing of AI outputs. One of them is the developer-based licensing where the license belongs to the developer of the AI or the company that owns the system. The Figure 3 describes the process of licensing that regulates the use of AI-generated music. The other is user based licensing where rights are given to those who enter in the creative instructions or parameters.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Architectural Diagram of Mechanisms for Licensing AI-Generated

Music

The third model is shared ownership where the rights are proportionately distributed among human contributors and the developers of AI systems. More digital systems allowing AI music creation, including Amper Music or AIVA, tend to run on a contractual licensing basis, where users can gain either full commercial license or restricted use license in relation to the subscription level. Besides, the use of blockchain and smart contracts in the automatization of royalty payment and transparent record-keeping is becoming a topic of investigation.

5.2. Collective Rights Management Challenges

The distribution of royalties to composers, lyricists and performers is traditionally done by collective rights management organizations (CRM) like ASCAP, PRS and BMI. Nonetheless, the emergence of AI-composed music breaks this pattern because it brings ambiguity as to who is the author, who owns and who is entitled to the compensation. Because AI does not have a legal personality, collective management societies find it challenging to decide who is to get royalties on AI-generated works. A major problem is who should be the rightful claimant, who should it be the programmer, AI developer, user, or the organization operating the AI platform. This ambiguity makes it difficult to assign accurate royalty and can result in copyright and abuse of the works. Moreover, the ever-growing volume of AI compositions is going to pressure the current collection systems to the point of devaluing payments to human composers. Further complications are brought by transparency and traceability. Devoid of an explicit metadata history or authorship statement, CRM organizations find it difficult to track the application of AI music in live performances, the streaming and synchronization licensing. In addition, absence of standardization of international standards brings discrepancies between jurisdictions.

5.3. Potential Frameworks for Equitable Distribution of Royalties

There should be a reconsidered structure of giving out royalty of AI-generated music where human contribution, technological invention, and ethical accountability are balanced. The traditional royalty schemes do not fit the AI compositions due to dependence on human creation and the performance rights institutions. Since AI is moving towards greater autonomy, then some form of a new mechanism is needed to help in the equitable distribution of revenues among stakeholders. A possible model is the hybrid rights model, in which royalties are shared between human participants (creators, users, data guards) and AI system owners depending on their creative and technical contribution. An example is that programmers designing the algorithm may get a share in technological innovation, and end users leading the creative process may get shares in compositional compensation. The other method is that of data-contributor compensation, which acknowledges the creators of works that are used in the process of training AI systems. This guarantees that there is ethical credit given to data beneath the datasets and that the question of unlawful data exploitation is averted. Blockchain technology can be used to make smart contracts in royalty payments, which will be distributed with transparency, accuracy, and in time.

6. Case Studies and Legal Disputes

6.1. Notable global cases involving AI music and IP

A number of high-profile cases across the globe have highlighted the legal issues that are associated with AI-generated music and the right to intellectual property. Among the most debated cases, one can single out Stephen Thaler v. U. copyright Office (2023), in which Thaler requested his artistic work to be granted a copyright under his AI system, known as Creativity Machine. The court of the U.S. denied the argument as it was noted that only human authorship is worth copyright protection. Even though the given case did not relate directly to music, it established an essential precedent of all AI-generated creative works, such as compositions. In 2020, another controversy of OpenAI Jukebox was when it created songs in the voice and style of many well-known artists, causing people to debate the infringement and likeness rights. Equally, Endel, a Berlin based AI company developing generative ambient soundscapes, was also under fire regarding ownership and licensing when its AI generated music was played on streaming sites. The other notable debate was in the United Kingdom whereby the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (CDPA 1988) was put to the test to establish whether computer-generated works could be granted to AI-assisted compositions. These examples highlight the increase in tension between technological progress and the out-of-date IP-systems. They disclose that even though AI-generated music may be as creative as human music, the legal entity of its creation is still unclear, thus leaving such works in a precarious situation under the present copyright laws.

6.2. Lessons Learned from Landmark Rulings

The results of recent decisions and controversies concerning AI-generated content point to the most important lessons of the future of intellectual property management. First, it is established through the courts that human copyright is always protected by the centrality of human authorship. Thaler v. confirms this principle. According to Perlmutter (2023) and previous rulings such as Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884), creativity has to be the work of the human mind and emotional desire in order to be a protected work. Second, developers and creators of AI should create ownership and use rights before implementation through a contract agreement. Such disputes like authorship, profit-sharing, and licensing may be avoided in case of legal clarity at the beginning. As an example, in partnerships with AI helping artists, to protect both human and technological input, joint authorship or derivative rights can be introduced. Third, such cases highlight the need to be transparent in AI training datasets. Copyright laws are another issue that creates many controversies since AI systems use copyrighted works without the owner being notified, which may amount to infringement. The next generation models should focus on the ethics of data and consent.

6.3. Emerging Trends in Dispute Resolution

With AI-generated music still being used to undermine legal norms, dispute resolution systems are shifting towards becoming more flexible and technologically integrated. A significant trend is the swing towards alternative dispute resolution (ADR) - such as mediation and arbitration - which fits the digital and AI-related cases. Such approaches offer rapid and affordable solutions than the conventional courts that tend to be unskilled in AI systems. The other trend that is emerging is the use of technological solutions like blockchain and digital ledger in the right check and the process of ownership tracking. The blockchain can create open records of the AI training data, creative input, generation, and output, thereby eliminating uncertainty in authorship and royalty-related arguments. Licensing deals can also be executed automatically using smart contracts, a process that makes the process fair and unchallenged with the need to take time in court. Regulatory agencies and other organizations in the creative industry worldwide are working together to develop standardized rules in the resolution of IP disputes in the field of AI. As an example, the Conversation on IP and Frontier Technologies organized by WIPO discusses novel dispute approaches that can be used in AI-generated content, whereas the EU is deliberating on having a dedicated digital tribunal where disputes related to emerging technologies may be resolved.

7. Conclusion

One of the most urgent questions in the relationship that develops between creativity and technology is management of intellectual property (IP) in AI-generated music. With the ongoing redefinition of musical composition by artificial intelligence, the traditional IP systems based on the authorship of humans, originality, and moral rights find it difficult to adapt to machine-generated creativity. AI systems like AIVA, MuseNet and Magenta prove that machines are capable of aping the work of human artists but since they lack the ability to be conscious, to have intent and to create feelings, this makes the attribution of authorship and ownership more challenging. Modern IP legislations in most jurisdictions such as the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, to a large extent, limit copyright to human authors. Although this assures protection of human ingenuity, it puts AI-generated works in a legal vacuum, and may deny the developers and users any economic rights and worse still, deter innovation. The initiatives of international bodies like WIPO and local regulating authorities are an indication that the issues are slowly being accepted but there has not been an agreement on a common approach. To guarantee fairness and sustainable management, policymakers and industry players should work together on adaptive structures that would balance between innovation and fairness. Some possible solutions are hybrid authorship, sui generis protection on AI output and blockchain-based transparent licensing to distribute royalty to automated agents. Ethical concerns, including the ability to give credit to contributors of the data and be transparent about the participation of AI should also be kept in focus.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Chomiak, T., Sidhu, A. S., Watts, A., Su, L., Graham, B., Wu, J., Classen, S., Falter, B., and Hu, B. (2019). Development and Validation of Ambulosono: A Wearable Sensor for Bio-Feedback Rehabilitation Training. Sensors, 19(3), Article 686. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19030686

Eftychios, A., Nektarios, S., and Nikoleta, G. (2021). Alzheimer Disease and Music Therapy: An Interesting Therapeutic Challenge and Proposal. Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease, 10(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4236/aad.2021.101001

Fchar, D., Melchiorre, A., Schedl, M., Hennequin, R., Epure, E., and Moussallam, M. (2022). Explainability in Music Recommender Systems. AI Magazine, 43(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/aaai.12056

Gonzalez-Hoelling, S., Bertran-Noguer, C., Reig-Garcia, G., and Suñer-Soler, R. (2021). Effects of a Music-Based Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation on Gait and Balance in Subacute Stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), Article 2032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042032

Grau-Sánchez, J., Münte, T. F., Altenmüller, E., Duarte, E., and Rodríguez-Fornells, A. (2020). Potential Benefits of Music Playing in Stroke Upper Limb Motor Rehabilitation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 112, 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.02.027

Marquez-Garcia, A. V., Magnuson, J., Morris, J., Iarocci, G., Doesburg, S., and Moreno, S. (2022). Music Therapy in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00246-x

Messingschlager, T. V., and Appel, M. (2023). Mind Ascribed to AI and the Appreciation of AI-Generated Art. New Media and Society, 27(6), 1673–1692. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231200248

Ning, Z., Chen, H., Jiang, Y., Hao, C., Ma, G., Wang, S., Yao, J., and Xie, L. (2025). DiffRhythm: Blazingly Fast and Embarrassingly Simple End-To-End Full-Length Song Generation with Latent Diffusion (arXiv:2503.01183). arXiv.

Ruth, N., and Müllensiefen, D. (2021). Survival of Musical Activities: When do Young People Stop Making Music? PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0259105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259105

Schneider, F., Kamal, O., Jin, Z., and Schölkopf, B. (2023). Moûsai: Text-To-Music Generation with Long-Context Latent Diffusion (arXiv:2301.11757). arXiv.

Tang, H., Chen, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., and Yang, N. (2021). The Efficacy of Music Therapy to Relieve Pain, Anxiety, and Promote Sleep Quality in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(12), 7299–7306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06152-6

Wei, J., Karuppiah, M., and Prathik, A. (2022). College Music Education and Teaching Based on AI Techniques. Computers and Electrical Engineering, 100, Article 107851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107851

Williams, D., Hodge, V. J., and Wu, C. Y. (2020). On the Use of AI for Generation of Functional Music to Improve Mental Health. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3, Article 497864. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2020.497864

Wittwer, J. E., Winbolt, M., and Morris, M. E. (2020). Home-Based Gait Training Using Rhythmic Auditory Cues in Alzheimer’s Disease: Feasibility and Outcomes. Frontiers in Medicine, 6, Article 335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2019.00335

Wu, Q. (2024). The Application of Artificial Intelligence in Music Education Management: Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering, 25(5), 2836–2848. https://doi.org/10.1177/14727978251322675

Yu, J., Wu, S., Lu, G., Li, Z., Zhou, L., and Zhang, K. (2024). Suno: Potential, Prospects, and Trends. Frontiers of Information Technology and Electronic Engineering, 25(7), 1025–1030. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.2400299

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.