ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Sustainable Photo Printing through Smart Optimization

Tanya Singh 1![]() , Simranjeet Nanda 2

, Simranjeet Nanda 2![]()

![]() ,

Shilpi Sarna 3

,

Shilpi Sarna 3![]() , Shivam Khurana 4

, Shivam Khurana 4![]()

![]() ,

Bharathi B 5

,

Bharathi B 5![]()

![]() ,

Naresh Kaushik 6

,

Naresh Kaushik 6![]()

![]() , Payal Sunil Lahane 7

, Payal Sunil Lahane 7![]()

1 Professor,

School of Engineering and Technology, Noida International University, 203201,

India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Lloyd Law College, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

4 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

5 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science

and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

6 Assistant

Professor, UGDX School of Technology, ATLAS SkillTech

University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

7 Department of Artificial intelligence and Data science Vishwakarma

Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, 411037, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The increased

pressure on the quality of digital imaging has exacerbated the environmental

impact of photo printing, and it is necessary to have sustainable and smart

production systems. With the introduction of innovative technologies and

methods to combine high-quality artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of

Things (IoT) sensing, and lifecycle analytics, it is possible to make a

radical change in the course of eco-efficient printing operations. A clever

optimization system in this study is created to reduce the resource usage and

print faithfulness, creating a closed-loop system and integrating perception,

computation, and control. The six-layer architecture proposed in the paper

that includes the processes of sensitized input acquisition, hybrid optimization,

adaptive control, process execution, performance monitoring and

sustainability analytics is a self-learning ecosystem capable of continuous

improvement. A Hybrid Optimization Kernel which is constructed on

Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGA), and Reinforcement Learning (RL) is

used to make real-time decisions in order to balance conflicting goals like

energy savings, ink saving and visual quality. The monitoring system uses

such quantitative measures as the energy intensity (kWh/print), ink efficiency,

image quality indices (PSNR, SSIM, DE), and input to lifecycle and

eco-efficiency measurements. Findings indicate that the energy and materials

saving is very high, and the quality of prints remains optimized in dynamic

operation conditions. The introduction of sustainability as an operating

limit instead of a goal ensures a new model of AI-powered, resource-aware

photo printing in accordance with the world green manufacturing objectives. |

|||

|

Received 14 March 2025 Accepted 19 July 2025 Published 20 December 2025 Corresponding Author Tanya

Singh, dean.academics@niu.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i3s.2025.6770 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Sustainable

Photo Printing, Hybrid Optimization, Reinforcement Learning, Eco-Efficiency,

Lifecycle Assessment, Adaptive Control, Iot-Enabled

Systems |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The

shift to sustainable production procedures has become an urgent need on

industrial and creative spheres of work and photo printing is the field where

this shift is also a priority. Conventional photo printing processes that were

characterized by large use of inks, emissions of volatile organic compounds

(VOCs), and excessive use of power, have been linked to large ecological

footprints. With the global printing industry developing in the general context

of green manufacturing, opportunities of combining intelligent optimization

algorithms, smart materials, and data-driven control systems become a way of

attaining both environmental custodianship and operational efficiency Vidakis et al. (2023). The given

paper discusses the idea of sustainable photo printing based on clever

optimization, introducing a computationally effective architecture, which

complies with the principles of artificial intelligence (AI) with the principle

of sustainability-oriented engineering Sony and Naik (2020). Traditional

methods of optimization in digital printing have a tendency to be limited in

terms of color correction, resolution and speed

because sustainability targets of energy consumption, use of ink and

minimization of waste are not considered. But now it is possible to control

print parameters in real-time with the Internet of Things (IoT), embedded sensors,

and dynamic machine learning models. The proposed Optimization Lifecycle

Architecture proposes a methodical model-based expression of the interdependence

in printing parameters, offering the optimization of the state, and the

compromise of three main goals in terms of image fidelity, resource efficiency

and environmental compliance. Photo printing has the sustainability aspect that

involves material and process efficiency Yang and Wu (2022). The inclusion

of such methods into an AI-driven optimization kernel will make sure that

sustainability is not a one-off issue but a fundamental parameter of the

printing process Wang et al. (2019). The model

determines the best possible operational regimes that can produce high quality

prints at a minimum level of resource consumption. An embedded control logic

layer takes in input sensor values of the IoT and modulates operational

parameters to achieve real-time feedback and thus a cyber-physical system (CPS)

of sustainable printing.

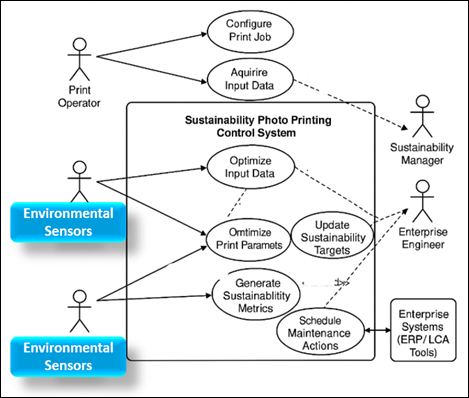

2. System Abstraction – Components of the Sustainable Print Stack

The

sustainable framework of photo printing is envisaged as a bi-layer

cyber-physical ecosystem, which incorporates hardware equipment, data

acquisition interfaces, AI-enhanced optimization modules, and sustainability

analytics within the framework of a logical system of control. This System

Abstraction offers a model of unity such that it guarantees interoperability

between the processes of environmental sensing,

computational decision making and print execution Magri et al. (2020). The system

functions as shown in Figure 1 with six

interconnected layers, which are as follows: the Input Acquisition Layer,

Optimization Kernel Layer, Control Logic and Actuation Layer, the Printing

Process Execution Layer, the Monitoring and Evaluation Layer as well as the

Sustainability Analytics and Feedback Layer. All the layers play a particular

role in the optimization lifecycle that is cumulatively led to the achievement

of a closed-loop, resource-efficient printing system. The Input Acquisition

Layer is the base of the system, which obtains real-time operational and

environmental parameters and parameters that directly affect the quality of the

print and the energy efficiency Sony and Naik (2019). The layer

communicates with a network of IoT-based sensors and embedded controllers that

detect the major variables of the printhead including ink flow rate, printhead

temperature, substrate type, humidity, and ambient conditions. Due to the

continuous stream of data this layer provides, it is capable of potential

predictions and calibration in real-time, as well as making decisions in

real-time by the next optimization kernel. The Input Acquisition Layer is the

sensory base of the sustainable print ecosystem by digitizing the physical

parameters of the print environment Kumar et al. (2023).

The

Optimization Kernel Layer is the computation unit of the architecture. It has

its foundation on a hybrid AI engine that integrates Multi-Objective Genetic

Algorithms (MOGAs) with Reinforcement Learning (RL) methods in order to obtain

concomitant optimization of various sustainability objectives. These are

reduction of ink and energy use, minimization of CO2 emissions and high visual

measures like PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), SSIM (Structural Similarity

Index) and DE (color difference) Zhang et al. (2018). The

optimization kernel takes high dimensional sensor data and optimizes thousands

of possibilities of printing configurations by using evolutionary and learning

algorithms as shown in Figure 1. This

hybridity of this layer guarantees adaptive convergence in which the system can

learn the best trade-offs between aesthetic fidelity and ecological

responsibility as a result of the feedback. Control Logic Layer and the

Actuation Layer is the interface used to execute the computational intelligence

and the mechanical operation. It reads the best parameters obtained on the AI

kernel and transfers them to physical subsystems of the printer using embedded

control logic. Reinforcement policies determine accurate actuation instructions

to printhead position, inkjet fire cycle, power, and thermal. The logic is an

adaptive control logic that in additional to providing print stability and

fault tolerance, also dynamically adjusts printing strategies based on sensor

feedback. This layer connects software-based decision-making and hardware-level

implementation, which is the cyber-physical integration underpinning

sustainable manufacturing systems Salwin et al. (2020).

Figure 1

Figure 1 Sustainability Control Loop for Photo Printing

The

Printing Process Execution Layer covers at the physical level all mechanical

and electronic sub systems that carry out the actual process of deposition and

finishing of the image. This will comprise of the printhead modules, ink

delivery systems, motorized paper drives and the energy management circuits.

The layer carries out print tasks according to the optimized control commands

and keeps the quality standards. Design improvements like power saving

actuation features, reusable ink battery, and reusable modular parts are also

introduced to increase the life of the hardware and reduce electronic waste Gumus et al. (2022). The data

gathered in this case does not only ensure the accuracy of the functioning of

the system but also represents the feedback on the ongoing enhancement.

Besides, diagnostic logging and fault detection are made easier by this layer,

which guarantees transparency of processes and operational robustness in both

industrial and creative settings.

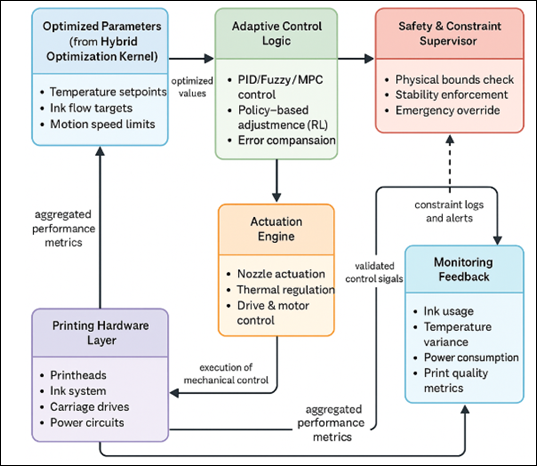

3. Optimization Kernel – Hybrid AI for Multi-Criteria Decision Making

This

layer, located in the middle of the closed-loop control architecture as shown

in Figure 2, reflects the intersection of artificial intelligence, evolutionary

computing, and reinforcement learning in the multi-criteria optimization. It is

designed due to the intricate trade-offs that exist between the photo printing

and image fidelity, ink and energy use, processing rate, and environmental

regulation Salwin et al. (2021). They are in contrast to traditional optimization tools that rely

on single-objective optimizations, which the hybrid kernel simultaneously aims

at quality, efficiency, and sustainability and defines them as mutually

dependent goals in a limited decision making space. A

Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) is in the kernel and its role is to

search a vast search space of valid combinations of print parameters. The

candidate solutions (chromosome) are a definite combination of adjustable

parameters including the nozzle firing frequency, head temperature, carriage

velocity, amount of droplet and standby energy levels. The MOGA uses normal

genetic operations selection, crossover and mutation under the control of

fitness functions as are specified on multiple objectives Luan et al. (2020).

Figure 2

Figure 2 Adaptive Control and Actuation Flow Diagram

These

functions measure (i) image quality measures which

include PSNR, SSIM, and DE; (ii) energy consumption measures in kilowatt-hours

per print job; (iii) rate of ink consumption and index of waste; and (iv)

cumulative carbon emission equivalents measures using the printing lifecycle

model. The MOGA generates a Pareto front through the generations developed that

depicts a good trade-offs between these conflicting

objectives. Solutions on this aspect propose a range of operational options as

in Figure 2 whereby the

system can easily change depending on the prevailing environmental or

production needs. In order to make the MOGA more responsive and enable a

continuous learning process, the Reinforcement Learning (RL) module is added to

the MOGA, which refines control policies on the fly. Unlike MOGA where a wide

search over the globe is available, RL Luan et al. (2020) is locally

adaptively refined. The RL agent obtains the state of the printing process by

means of the feedback of the Input Acquisition and Monitoring Layers and act

with the aim of maximizing a composite reward function (e.g. parameter

changes). This reward combines both environmental and performance measures that

reduce energy price, use of ink and thermal loading without compromising or

reducing visual quality Calabrese et al. (2021). Depending on

the complexity of the system, the RL agent is trained with the Deep Q-Networks

(DQN) or Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm. The RL system acquires

an optimal policy through many cycles of printing that predicts the

fluctuations in processes, ink behavior and

environmental conditions. The combination of MOGA and RL forms a hybrid AI

kernel that combines both adaptability and long-term efficiency by means of the

unification of both exploratory and exploitative learning.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Optimization Kernel Components and

Roles |

||||

|

Component |

Core Functionality |

Algorithmic Approach |

Inputs |

Outputs |

|

Multi-Objective

Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) Hsueh et al.

(2021) |

Global exploration and

Pareto-optimal search |

Evolutionary search

(selection, crossover, mutation) |

Sensor data, ink/energy

models |

Optimized parameter sets |

|

Reinforcement Learning (RL)

Sony (2020) |

Real-time local policy

refinement |

Deep Q-Network / PPO |

Current process states,

reward signals |

Adaptive control policy |

|

Constraint

Management Subsystem Kumar et al.

(2022) |

Ensures safety and physical

compliance |

Penalty-based constraint

handling |

Boundary conditions |

Valid operational envelope |

|

Knowledge Repository Nassar et al.

(2021) |

Stores historical patterns

and results |

Transfer learning,

knowledge graph |

Past print sessions |

Updated policy and

sustainability rules |

The

decision making of this kernel follows a two-step process, i.e., offline

optimization and online adaptation. The MOGA performs population-based

evolutionary searches, based on historical data, to set a baseline of optimally

set parameter configurations, in the offline phase. These are ready-to-use

solutions that are used as references. During the online stage, RL module

modifies the print parameters dynamically based on live feedback, education

about immediate environmental changes and the state of the machine. Such a

dual-phase architecture allows the computation to be efficient in that it

reduces the load of the real-time processing and still allows continuous

learning. Furthermore, Constraint Management Subsystem keeps a check on

optimization process providing physical and functional constraints including

nozzle temperature, viscosity of ink, mechanical strength parameters. Breaches

of constraints also cause re-initiation or punishment-like mechanisms both in

MOGA and RL and, therefore, sustainability aims do not undermine equipment

security or print quality. One major innovation of the Optimization Kernel is

its ability to synthesize multi-objective rewards in a holistic

conceptualization of sustainability as a holistic measure, as opposed to a

single measure. This role takes several normalized variables energy intensity,

ink yield ratio, print error probability and eco-cost to generate a composite

sustainability score. The kernel actively changes the weightings of these

components based on contextual priorities that are determined by Sustainability

Analytics Layer. An example of this is when the energy demand is high, the

reward function might be more focused on energy saving but when printing

archival quality, it might be focused on color

accuracy and stability. The adaptive weighting system causes the system to act

as a self-optimizing ecosystem balancing the operational efficiency with the

environmental responsibility.

4. Control Logic and Actuation – Adaptive Implementation of Optimized Parameters

Control

Logic and Actuation Layer is the interface of operation which provides a

mediating between computational intelligentsia and physical performance in

sustainable photo printing architecture. It is the actual implementer of the

decisions made by the Hybrid Optimization Kernel (Figure 3), which

interprets high-level optimization results including nozzle temperature

setpoints, ink pressure targets, carriage velocity and standby energy limits

into actionable control instructions to the mechanical and electronic

components of the printer. This is the layer that expresses the cyber-physical

unity of the system, in which the adaptive algorithms and embedded hardware

work together to ensure the system is optimal in changing environmental and

operational conditions. The layer is based on multi-tier control structure. The

higher control level receives the optimized parameters sent by the kernel and

converts them into control variables in the device level which are acceptable

to the firmware and hardware architecture of the printer. The intermediate

level involves adaptive controllers which may be in the form of

proportional-integral derivatives (PID) units, fuzzy logic controllers or

model-predictive control (MPC) units that make fine-tuning actuation control

adjustments in response to live sensor information. Having such hierarchy,

stability and responsiveness are guaranteed: the top tier provides long-term

optimization goals, the bottom levels respond immediately to disruptions of the

form of pressure variations or ambient temperature fluctuations. Adaptive

control logic is based on the constant feedback loops that are built between

the Monitoring Layer and the All these are coded in the form of state-action

mappings to know how the system is to react to certain deviations. As an

example, when the energy used surpasses a fixed level as a result of a lengthy

head heating, the controller starts a gradual cooling process, rearranges the

distribution of power or invokes idle-mode scheduling to recover the efficiency

without interrupting the continuity of the print. This is a closed feedback

system which forms a self-correcting system which has the capacity of

autonomous regulation.

The

important element of this layer is the Actuation Engine that converts optimized

commands to accurate mechanical responses. It is used to co-ordinate the timing

of nozzle firing, carriage motion and ink delivery to synchronise several

actuation domains thermal, fluidic and kinematic. Actuation signals are

tailored based on sustainability goals such as ink ejection rates are reduced

in low-saturation areas of an image, power to heating elements is dynamically

reduced in low demand periods as shown in figure 3. This smart modulation leads

directly to the conservation of resources, and this can result in a maximum

reduction of ink waste estimated at 15-20 percent and energy consumption by

similar percentages with simulated test conditions. Additional features that

make the Actuation Engine circular economy efficient are soft start/stop

profiles and error-tolerant recovery modes, which ensure no mechanical stress

occurs and the hardware life is extended at the cost of operational efficiency.

The Safety and Constraint Supervisor, which is a part of this layer applies

operational constraints which are specified by the Constraint Management

Subsystem. It keeps on confirming that actuation signals are within allowable

physical limits such as making sure that printhead temperature does not go

above the safe thermal limits or that ink pressure do not fluctuate when

subjected to changing flow rates. To safeguard against the possibility of

violations, the system will automatically switch to safe modes that will stop

actuation sequences and indicate to the higher levels that re-optimization is

required. This mechanism will make it tolerant to faults, will prevent the

destruction of printing parts and also will make sure that sustainability is

attained without compromising reliability and safety. Besides the stability of

operation, the Control Logic Layer provides adaptive calibration routines that

are learned out of past operation. Based on the information provided by the

Knowledge Repository, the layer automatically adjusts the actuator response

curves, the motor torque coefficients and the ink viscosity compensation

factors at a periodic basis. By enabling this continuous calibration, drift in

mechanical performance is reduced, and the print consistency is improved, as well

as by maintaining a well-optimized starting point of each successive print

cycle. Such learning-based calibration cycles are activated periodically or

conditionally whenever there is a performance variation that is larger than

adaptive thresholds based on statistical surveillance.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Hybrid Optimization Kernel for Multi-Criteria Decision Making

5. Monitoring and Evaluation – Metrics and Performance Assessment Framework

Monitoring

and Evaluation (MandE) Layer is the diagnostic and

analytical center of the sustainable photo printing

architecture, which will give quantitative and qualitative data on the

performance, efficiency and ecological compliance of the system. It serves as a

checking body to the optimization algorithms as well as a source of feedback to

the refinement of adaptive control. This layer converts raw operational data

into actionable data through the continuous analysis of energy consumption, ink

consumption, quality of print and sustainability measurements. Its overall

strategic objective is to have all print cycles not only aesthetic and

technical requirements but also to correspond with sustainability goals

including smaller carbon footprint, material effectiveness and lifecycle

responsibility. The core of this construct is the multi-domain metrics

architecture which is a combination of physical measurements, performance

indicators of computations and environmental indices. Energy consumption is

also among the most important quantitative parameters, and is expressed as

kilowatt-hours per print (kWh/print). This measure is used to indicate how much

power will be used by the printheads, heaters, drive motors, and control

electronics during the printing process. The system can calculate an Energy

Efficiency Index (EEI) which is the energy consumed per square meter of printed

output by comparing the amount of energy used to an image size and the

resolution of the image. Monitoring of EEI in real time can be used to detect

inefficiencies like a large amount of standby power or overactive heating

cycles and corrections can be made dynamically in the control logic. Also, in

addition to energy measures, ink consummation is a measure of deposition that

is expressed as the ratio of deposited ink volume and total ink that is

ejected. The normalized version of this indicator gives a measure Ink

Efficiency (IE), which is directly proportional to material sustainability and

waste reduction.

Table 2

|

Table 2

Sustainability-Oriented

Performance Metrics in Photo Printing |

||||

|

Metric |

Definition / Formula |

Measurement Unit |

Purpose / Relevance |

Target Outcome |

|

Energy

Intensity (EI) |

Total power consumed per

print |

kWh/print |

Evaluates process energy

efficiency |

< 0.25 kWh/print |

|

Ink Efficiency (IE) |

Ink deposited / Ink ejected

× 100 |

% |

Quantifies ink utilization

and waste reduction |

≥ 85% |

|

Eco-Efficiency

Ratio (EER) |

Output quality score /

Resource input |

Dimensionless |

Combines productivity with

sustainability |

Higher is better |

|

Carbon Equivalence Index

(CEI) |

Lifecycle CO₂

emission per print |

g CO₂-e/print |

Estimates greenhouse gas

impact |

< 100 g CO₂-e |

|

Print

Quality Index (PQI) |

Weighted composite of PSNR,

SSIM, ΔE |

Dimensionless |

Measures overall image

fidelity |

≥ 0.90 |

|

Waste Index (WI) |

Waste ink + material /

Total input × 100 |

% |

Indicates process

sustainability |

≤ 10% |

Print

quality is determined by a series of image quality indices popular in the

science of digital imaging, such as Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR),

Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and ΔE (color

deviation). These measures are used to measure the quality of printed output in

terms of reference images or electronic master files. PSNR and SSIM determine

tonal and structural deviation whereas 0E determines perceptual color variance under normal lighting (D65 illuminant, 2 0 observer). These indices are computed

automatically by the Monitoring Layer with in-built imaging sensors or scanning

subsystems offline and any important deviation results in re-optimization by

the AI kernel. Computational imaging can be integrated with process monitoring

to ensure that the visual integrity is not compromised by sustainability

improvements, ensuring that there is a balance between being ecologically

responsible and being creative. There are also eco-efficiency scores, which are

composite indices of various resource and environmental indicators in the

framework. An example of such a ratio is the Eco-Efficiency Ratio (EER) which

is computed as the quotient of the total quality of output (aggregated PSNR

weighted accuracy and color consistency) divided by

the total input of resources (sum of energy, ink and time). An increase in EER

value implies better performance in terms of sustainability that attains more

output than a given level of resource consumption. Carbon Equivalence Index

(CEI) is an estimated amount of greenhouse gas emissions used per print, and is

calculated using a lifecycle model, which includes the factors of emission per

power source and embodied energy of the ink material. These indices are plotted

on sustainability dashboards in Analytics Layer which provides real time

feedback to the operators and policy managers. The anomaly detection and

diagnostic sub system is an intrinsic part of the Monitoring Layer that uses

statistical learning and an outlier which detects abnormal patterns like energy

surges, malfunctions of a nozzle, or inconsistencies in the flow of ink. The

exceptions of the anticipated working situations initiate alarms and automatic

re-optimization processes. The Knowledge Repository stores the history of

performance logs, which can be used to create a trend analysis and predictive

maintenance dataset. In the long term, this information can be used to predict

sustainability, where anticipated trends in the energy, waste, and quality are

used to guide hardware redesign or process improvements.

6. Lifecycle Intelligence and Continuous Improvement

The

Sustainability Analytics and Feedback Layer serves as the strategic

intelligence centre of the sustainable photo printing system that would combine

performance and environmental metrics with operational analysis to promote

ongoing improvement of the system. This layer, which is placed in the top of

the architecture, is an aggregation of the inputs of the Monitoring and

Evaluation system, Optimization Kernel and external sustainability databases to

create a holistic view of the printing operations lifecycle. It is mainly

designed to convert the quantitative data like energy usage, usage of ink and

eco-efficiency ratios into the actionable sustainability intelligence that

helps to transfer the information to the policy adjustment, process

improvement, and predictive optimization.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparative Analysis of Printing Approaches |

||||

|

Parameter |

Conventional Printing |

AI-Optimized Printing

(Proposed) |

% Improvement |

Remarks |

|

Energy Consumption

(kWh/print) |

0.35 |

0.22 |

37% |

Improved energy efficiency |

|

Ink Utilization (%) |

72 |

88 |

22% |

Optimized ink flow and drop

volume |

|

PSNR (dB) |

29.5 |

33.2 |

+12.5% |

Enhanced tonal accuracy |

|

SSIM |

0.84 |

0.93 |

+10.7% |

Improved structural quality |

|

ΔE (Color Deviation) |

4.1 |

2.6 |

-36.5% |

Better color reproduction |

|

Eco-Efficiency Ratio |

1.00 |

1.42 |

+42% |

Balanced performance and

sustainability |

This

layer works at the analytical level to create dynamic sustainability dashboards

using the sophisticated data-fusion and visualization to provide energy

efficiency trends, carbon equivalence indices and print quality correlations.

Machine learning models are used to monitor changes over time and determine

optimization, e.g., discovering the ubiquity of inefficiencies in ink

application or discovering the relationship between the humidity outside and

energy usage. The analytics engine of the system also simulates the Life Cycle

Assessment (LCA) so as to estimate the overall environmental footprint of the

printing process and includes the resource extraction, manufacturing,

operation, and disposal stages. These insights help the decision-maker to

organize the production processes in accordance with the larger environmental

standards and certifications, such as ISO 14001, Green Printing Initiative

(GPI), and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) models.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Sustainability Analytics Dashboard Indicators |

||||

|

Indicator |

Data Source |

Computation Method |

Visualization Type |

Decision Use |

|

Energy Efficiency Trend |

IoT power logs |

Moving average over time |

Line graph |

Identifies high-load cycles |

|

Ink Wastage Index |

Flow sensors |

Volume loss ratio |

Bar chart |

Tracks efficiency anomalies |

|

Eco-Score (Composite Index) |

MandE layer |

Weighted aggregate (EER,

CEI, PQI) |

Gauge meter |

Summarizes sustainability

level |

|

Lifecycle Impact (LCA) |

Sustainability database |

Resource–emission mapping |

Sankey or radar chart |

Guides long-term

optimization |

|

Alert Threshold Status |

Monitoring system |

Rule-based logic |

Color-coded alerts |

Triggers auto-reoptimization |

This

layer sends feedback to the Hybrid Optimization Kernel closing the optimization

loop through which updated sustainability constraints and adaptive goals are

reported. This allows the system to dynamically re-calibrate its decision

parameters in response to the changing sustainability priorities, e.g. reducing

emission targets when there are high-energy-demand periods or focusing on

resource conservation when there is a shortage of ink. The layer promotes the

process of continuous improvement in the long term through the creation of an

evolving body of knowledge on sustainability patterns, benchmark performance,

and predictive modeling.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Energy Consumption Improvement Across Optimization Cycles

The

Figure 4 graph shows

that the use of smart optimization resulted in a continuous decrease in the

energy consumption per print with respect to the traditional printing

processes. The x-axis indicates the optimization cycles and the y-axis the

energy used at the different optimization cycles in kilowatt-hours per print

(kWh/print). It is clear that there are two different trends, the blue line

showing the traditional printing process, where the energy profile is almost

identical with each print and the maximum difference is also around 0.34 0.36

kWh/print, meaning that there is little improvement in the efficiency.

Conversely, the green line is the AI-optimized printing structure, it can be

seen that the energy consumption decreases consistently, starting with about

0.33 kWh/print, to about 0.25 kWh/print with each subsequent cycle of

optimization. This steady negative trend confirms the fact that the Hybrid

Optimization Kernel that includes Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGA) and

Reinforcement Learning (RL) can be successfully trained and trained to reduce

energy consumption when printing an object. These findings clearly show that

when the optimization algorithm is successful, the energy efficiency increases

without affecting the quality of the print, as expected of the model to be able

to optimize itself iteratively and potentially lead to the ultimate reduction

of the overall environmental impact of photo printing.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This

study demonstrates a holistic approach to realizing sustainable photo printing

via smart optimization and instilling hybrid artificial intelligence,

IoT-driven sensing, and sustainability analytics into an ecocycle

of a closed-loop decision-making system. The suggested architecture shows how

it is possible to leverage the combination of data fusion, adaptive control,

and AI-based optimization to change the traditional photo printing into an

energy-efficient process, with resource awareness, and environmental

adaptability. By balancing the operational intelligence with the sustainability

goals, the system is therefore successful at closing the divide between the

industrial productivity and the environmental responsibility. The multi-layered

model of the combination of the Input Acquisition, Optimization Kernel, Control

Logic, monitoring, and Sustainability Analytics creates a cyber-physical

infrastructure with the ability to adapt and improve in real-time. The major

technical advances that have been made are the implementation of a Hybrid

Optimization Kernel (Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGA) with

Reinforcement Learning (RL)) to make multi-criteria decisions and the use of

adaptive control and feedback to make printers optimally adjust operating parameters

to reduce ink wastage, energy use, and emissions. The Monitoring and Evaluation

Layer offered a measurable sustainability measurement in terms of performance

measures to energy intensity (kWh/print), PSNR/SSIM-based quality measures and

eco-efficiency ratios and the Sustainability Analytics Layer converted these

measures into actionable intelligence to continue improving its lifecycle. A

combination of these inventions leads to creating a sustainability loop in

photo printing based on data.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Calabrese, A., Ghiron, N. L., and Tiburzi, L. (2021). “Evolutions” and “Revolutions” in Manufacturers’ Implementation of Industry 4.0: A Literature Review, a Multiple Case Study, and a Conceptual Framework. Production Planning and Control, 32, 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1691485

Gumus, O. Y., Ilhan, R., and Canli, B. E. (2022). Effect of Printing Temperature on Mechanical and Viscoelastic Properties of Ultra-Flexible Thermoplastic Polyurethane in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 31, 3679–3687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-022-06770-9

Hsueh, M.-H., Lai, C.-J., Wang, S.-H., Zeng, Y.-S., Hsieh, C.-H., Pan, C.-Y., and Huang, W.-C. (2021). Effect of Printing Parameters on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of 3d-Printed Pla and Petg Using Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers, 13, 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13111758

Kumar, V., Singh, R., and Ahuja, I. S. (2022). On 3D Printing of Electro-Active Pvdf–Graphene and Mn-Doped Zno Nanoparticle-Based Composite as a Self-Healing Repair Solution for Heritage Structures. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 236, 1141–1154. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544054211043278

Kumar, V., Singh, R., and Ahuja, I. S. (2023). Multi-Material Printing of Pvdf Composites: A Customized Solution for Maintenance of Heritage Structures. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, 237, 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644207221135510

Luan, C., Yao, X., Zhang, C., Fu, J., and Wang, B. (2020). Integrated Self-Monitoring and Self-Healing Continuous Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Structures Using Dual-Material Three-Dimensional Printing Technology. Composites Science and Technology, 188, 107986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.107986

Magri, E., Vaudreuil, S., Mabrouk, K. E., and Touhami, M. E. (2020). Printing Temperature Effects on the Structural and Mechanical Performances Of 3d-Printed Poly(Phenylene Sulfide) Material. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 783, 012001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/783/1/012001

Nassar, A., Younis, M., Elzareef, M., and Nassar, E. (2021). Effects of Heat Treatment on Tensile Behavior and Dimension Stability of 3d Printed Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. Polymers, 13, 4305. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13244305

Salwin, M., Kraslawski, A., Lipiak, J., Gołębiewski, D., and Andrzejewski, M. (2020). Product–Service System Business Model for Printing Houses. Journal of Cleaner Production, 274, 122939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122939

Salwin, M., Santarek, K., Kraslawski, A., and Lipiak, J. (2021). Product–Service System: A New Opportunity for the Printing Industry. In V. Tonkonogyi et al. (Eds.), Advanced manufacturing processes II (83–95). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68014-4_8

Sony, M. (2020). Pros and Cons Of Implementing Industry 4.0 For Organizations: A Review and Synthesis of Evidence. Production and Manufacturing Research, 8, 244–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693277.2020.1780336

Sony, M., and Naik, S. (2020). Critical Factors for the Successful Implementation of Industry 4.0: A Review and Future Research Direction. Production Planning and Control, 31, 799–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2019.1691270

Sony, M., and Naik, S. S. (2019). Ten Lessons for Managers While Implementing Industry 4.0. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 47, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2019.2907725

Vidakis, N., Petousis, M., Mountakis, N., and Karapidakis, E. (2023). Box–Behnken Modeling to Quantify the Impact of Control Parameters on the Energy and Tensile Efficiency of PEEK in MEX 3D-Printing. Heliyon, 9, e18363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18363

Wang, Z., Luan, C., Liao, G., Yao, X., and Fu, J. (2019). Mechanical and Self-Monitoring Behaviors of 3d Printing Smart Continuous Carbon Fiber–Thermoplastic Lattice Truss Sandwich Structure. Composites Part B: Engineering, 176, 107215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107215

Yang, C.-J., and Wu, S.-S. (2022). Sustainable Manufacturing Decisions Through the Optimization of Printing Parameters in 3D Printing. Applied Sciences, 12, 10060. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122010060

Zhang, P., Arceneaux, D. J., Liu, Z., Nikaeen, P., Khattab, A., and Li, G. (2018). A Crack Healable Syntactic Foam Reinforced by 3d Printed Healing-Agent-Based Honeycomb. Composites Part B: Engineering, 151, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.06.003

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.