ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Evaluating Artistic Creativity through Neural Models

Dr. Quazi Taif Sadat 1![]() , Dr. Arun Kumar Tripathi 2

, Dr. Arun Kumar Tripathi 2![]()

![]() , Mohit Gupta 3

, Mohit Gupta 3![]()

![]() , Dr. Swati Sachin Jadhav 4

, Dr. Swati Sachin Jadhav 4![]() , Tannmay Gupta 5

, Tannmay Gupta 5![]()

![]()

1 Director,

Bangladesh University, Bangladesh

2 Professor,

Department of Computer Science, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal

Pradesh, Solan, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Basic Science, Humanities, Social

Science and Management, D Y Patil College of Engineering, Akurdi Pune, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome,

Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The increasing

overlap of artificial intelligence (AI) with artistic creativity is an

exciting prospect of learning more about how machines may be used to copy,

enhance, or even recreate human creative behaviors. In this paper, the neural

frameworks of self-assessment of artistic creativity are discussed with

reference to the generative models of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs),

diffusion models, and transformer-based frameworks. Although the art created

by AI is still developing and getting more advanced and diverse, the issue of

evaluating creativity remains a multi-dimensional problem. We suggest a

holistic assessment system, which combines both quantitative and qualitative

assessment methods in order to measure creativity in visual, textual, and

auditory contexts. The quantitative analysis is based on objective

measurements, i.e. originality, diversity, aesthetic coherence, to which

statistical standards and comparisons with other models are applied. Instead,

the qualitative framework focuses on a human based assessment that considers

the expert judgement, crowd-sourced assessment, and cognitive views of

emotional and psychological involvement. The study will fill the gap between

algorithmic generation and perceptual appreciation of art by taking a hybrid

approach to it by combining computational and humanistic perspectives.

Experimental results show the different neural structures that exist to

communicate different creativity types and how these can be experimentally

tested in a systematic protocol. Finally, the study leads to a better

comprehension of the creative potential of AI and creates a systematic

approach to assessing artistic innovativeness in the computational systems. |

|||

|

Received 08 February 2025 Accepted 30 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Quazi

Taif Sadat, taif@bu.edu.bd DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6750 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Artificial Creativity, Neural Models, Generative

Art, Creativity Evaluation, Computational Aesthetics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Creativity has also been considered as one of the most distinctive and complex characteristics of human intelligence. It contains in itself the power to produce new, useful and emotionally compelling ideas or products which are not tied to established routines of thought. In the realms of art, creativity is a fusion of imaginary, aesthetic and cognitive interpretation-aspects that are not only deep-rooted within human experience-and culture-development. Nevertheless, with the fast development of artificial intelligence (AI), there has been a paradigm shift, as human and machine creativities are no longer separate. Due to the development of powerful neural models, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), diffusion models, and transformer-based architectures, machines have now the capability to create paintings and artworks that are similar in complexity, range, and expressiveness to those made by human beings. This revolution has brought both interest and controversy: Is it really creative or is it only a copying of patterns based on human information? Neural models as a way to evaluate artistic creativity are a very great interdisciplinary problem. Although it is possible to discuss AI-generated art in terms of computational measures, e.g., newness, variation, and beauty, they alone cannot fully define the nature of creative expression that is subjective and context-specific, in many cases Shao et al. (2024). A valuable evaluation system should thus be an integrative experience of both quantitative and qualitative approaches that bring together the computational and human-oriented evaluation. This two-fold method is necessary in knowing not only what machines can produce, but how, and why, the results are viewed as a creative product or something otherwise. New developments in generative modeling have made the field of AI-generated art quite broad. An example of AI such as GANs has shown impressive features such as creating extremely realistic images and abstract compositions via adversarial learning Leong and Zhang (2025).

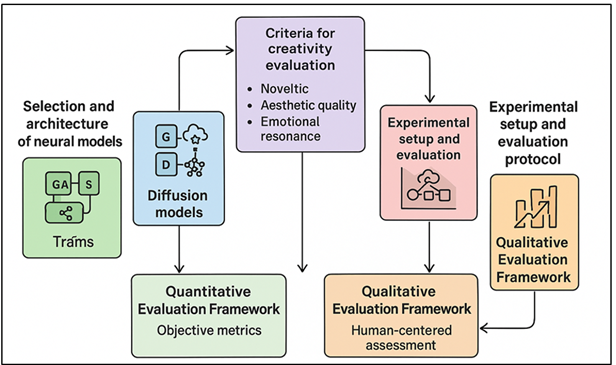

The diffusion models, which progressively sharpen noise into patterned structures, have been more effective than the previous models in creating high-resolution images, which are aesthetically appealing. Transformers, which were initially created in the natural language processing field, have been adapted to multimodal creativity, allowing systems such as DALL•E, Midjourney, and MuseNet to be used to produce cross-domain artistic expressions, using text and image as well as sound. Through these innovations, an agreed system of assessing creativity is however elusive Leong and Zhang (2025). Figure 1 presents the conceptual architecture that assesses artistic creativity with the help of neural networks. Recent studies tend to be based on disparate approaches: algorithmic tests of statistical distinctiveness, subjective polls of human preference, without defining a unifying framework that cuts across the process and the computationalism of creativity.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual Architecture of Artistic Creativity

Evaluation in Neural Networks

The proposed work is designed to fill in the said gap as it suggests an integrative model of artistic creativity evaluation based on neural models. The framework is intended to measure the objective and subjective aspects of creativity: originality, diversity, and aesthetic quality on one side, and affect on the other, emotional resonance, richness of interpretation, and understanding of human beings. Its methodology focuses on a comparative study of various neural structures in order to establish the position of model design in creative possibility Lou (2023). Moreover, it integrates cognitive and psychological research of creativity to put the generative nature of AI into the human artistic paradigms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical foundations of creativity in art and cognitive science

The notion of creativity has been discussed in a variety of fields, including neuroscience and aesthetics as well as philosophy and psychology. In arts, creativity has been regarded as an act of giving birth to new memorable and significant manifestations that have an emotional or intellectual impact. Immanuel Kant and John Dewey were some of the philosophers who focused on the creativity as an imaginative action as well as experiential action- an act that incorporates the synthesis of intuition, perception and cognition Guo et al. (2023). Cognitive scientists, however, view creativity as a problem-solving process or a divergent thinking process where the mind takes unusual directions to come up with original solutions. Psychologically, theories, such as the Structure of Intellect by Guilford and the systems theory by Csikszentmihalyi, have emphasized the role of creativity as an interplay between individual cognition and the social environment as well as the domain-specific knowledge. Neuroscientific studies have also found out that creativity is a complicated network of the brain, and it comprises both default mode network (the quality of spontaneous thought) and executive control network (the quality of focus and assessment) Cheng (2022). Creativity in the field of art also reflects the emotional control, as well as figurative speech, and the artist can transform subjective experience into concrete form of aesthetics. These theoretical foundations are very crucial in assessing AI creativity.

2.2. Computational creativity and AI-based artistic generation

The term computational creativity describes the research and implementation of systems with potential to accomplish work that would otherwise be considered a creativity task when performed by humans. The discipline grew out of initial studies into algorithmic art and generative systems, in which models of aesthetical choice were made using rules Oksanen et al. (2023). In the long run, machine learning, and especially deep learning, integration has transformed creative computation since it allows systems to independently acquire artistic qualities and produce original art. The groundbreaking use of adversarial training between a discriminator and a generator introduced Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to a new chapter of AI-based art, with the images produced being super-detailed and with a wide range of styles Xu et al. (2023). Diffusion models have also promoted the state of generative quality with probabilistic denoising procedures enabling greater continuity, more nuanced and semantically rich visual generations. Transformer architecture, especially the multimodal versions, has broadened the scope of computational creativity beyond one domain of creative work - now AI can produce not only visual art, but also poetry, music, and even cross-modal creative works Xu (2024). These technologies have been the source of controversy regarding authorship, intentionality, and ontology of creativity of its own.

2.3. Evaluation metrics in existing AI art research

Assessing AI generated art is still one of the most difficult areas of research into computational creativity. Conventional measures of performance such as the accuracy or loss do not reflect the subjective or complex nature of creativity that includes novelty, aesthetic quality, coherence and emotional appeal Hafiz et al. (2021). Consequently, scholars have suggested a variety of quantitative and qualitative methods of assessing AI artworks. Inceptor score (IS), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), and learned perceptual image patch similarity (LPIPS) are among the most commonly used measures of originality, diversity, and perceptual quality of generative works quantitatively Niu et al. (2021). These measures give statistical estimates of the difference and visual persuasiveness between works created by AI and those created by a human. Nevertheless, they tend to overlook more artistic and emotional aspects. Qualitatively, researchers use human-based assessments of perceived creativity, emotional strength, and conceptual richness by means of expert reviews, aesthetic questionnaires, as well as crowd-sourcing ratings Brauwers and Frasincar (2021). Table 1 presents a summary of the studies on AI-based artistic creativity evaluation. Other frameworks use hybrid methods, using computational metrics with human feedback used to estimate more holistic judgements. Other approaches of the future include neuroaesthetic and affective computing technologies, including monitoring viewer reactions or brain activity, to measure the emotional connection to AI art.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work Summary in AI-Based Artistic Creativity |

||||

|

Approach |

Domain |

Dataset Used |

Methods |

Limitations |

|

GAN (Original) |

Visual Art |

CIFAR-10, CelebA |

FID, IS |

Mode collapse, limited

diversity |

|

DCGAN |

Visual / Abstract |

LSUN, WikiArt |

FID, Diversity Score |

Limited creative control |

|

CycleGAN |

Style Transfer |

Monet2Photo |

Human Evaluation |

Overfitting to styles |

|

StyleGAN Liu et al. (2021) |

Portrait and Abstract Art |

FFHQ |

FID, IS, Aesthetic Ratings |

Lacks conceptual depth |

|

Diffusion Models |

Visual Art |

ImageNet |

FID, CLIP Similarity |

High computational cost |

|

DALL·E (Transformer) |

Text-to-Image |

Custom Text–Image Pairs |

CLIP Score, Human Judgment |

Occasional semantic drift |

|

GLIDE Ramesh et al. (2022) |

Text-guided Diffusion |

LAION Subset |

CLIP, FID |

Limited emotional evaluation |

|

Imagen |

Text-to-Image |

COCO Captions |

CLIP, Human Preference |

Dataset bias in prompts |

|

ChatGPT + DALL·E 3 Png et al. (2024) |

Multimodal Creativity |

Proprietary |

Human Feedback |

Hard to quantify creativity |

|

RAVE (VAE-based) |

Audio / Music |

NSynth |

Spectral Coherence |

Limited generalization |

|

MusicLM (Transformer) |

Text-to-Music |

AudioCaps |

BLEU, CLAP Similarity |

Subjective emotion mapping |

|

AICAN |

Visual Abstract Art |

Custom Art Dataset |

Expert Review |

Small-scale subjective testing |

|

CLIP-Guided GAN |

Visual Semantics |

WikiArt |

CLIP Score, Aesthetic Rating |

Dependence on text bias |

3. Methodology

3.1. Selection and architecture of neural models

1) GANs

To create an image, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were proposed by Ian Goodfellow in 2014, which is a two-player minimax game, with one player being a generator and the other a discriminator. The generator generates samples of data that are supposed to resemble actual ones and the discriminator checks their authenticity. GANs are trained through an iterative adversarial process to create an extremely realistic image and with a wide range of styles, especially applied to visual art and image generation. Other variants such as StyleGAN and CycleGAN have gone further to enhance creative control such as style transfer, abstract image transformation, and high-resolution image generation. GANs are central to the study of artistic creativity because of their ability to model the nature of complex aesthetic patterns although they have drawbacks such as mode collapse and training instability.

2) Diffusion

models

Diffusion models are a more recent paradigm of generative modeling, which denoises random noise by the use of successive denoising autoencoders. These models are based on the thermodynamic processes of diffusion and they are trained to unlearn a sequence of stochastic noise additions to recreate structured data like an image or audio. Models such as DALL didn’t even have to be shown as the DALL•E 3, Imagen, and Stable Diffusion show a high fidelity, semantic consistency, and visual consistency when compared to preceding approaches. Diffusion-based models are very successful at generation that can be controlled and fine detail synthesis, which means that artists and researchers can control creative outputs by providing textual prompts or conditioning images. They are effective because of their stability and interpretability in studying creativity in art generation guided by AI.

3) Transformers

Transformers, presented by Vaswani et al. in 2017 changed deep learning when their self-attention mechanism was proposed, and it allows processing sequential data and understanding context in long dependencies simultaneously. Transformers were originally used with natural language processing on natural language processing tasks, but have since been applied to multimodal creative tasks such as text, visual art, music, and even cross domain synthesis. CLIP, GPT and Vision Transformers (ViTs) are a few examples that combine linguistic and visual understanding to produce context rich and imaginative results. Transformers are creative in producing artworks through the combination of semantics, narrative coherence, and aesthetic reasoning to produce a subtle interpretation of creative prompts. Their flexibility in terms of modalities makes them the key architectures in the assessment of neural creativity.

3.2. Criteria for creativity evaluation (novelty, aesthetic quality, emotional

resonance, etc.)

Creativity measurement in neural modeling needs to be evaluated using a multidimensional construct that takes into consideration both the quantifiable and perceptual aspect of artistic production. The conventional definition of creativity has three fundamental qualities namely novelty, value and surprise but in computational creativity, the definition should be expanded to include aesthetical, emotional and contextual aspects. Novelty evaluates the extent to which the output that is generated is different to the existing works or patterns in the dataset. This may be measured using diversity indices or latent space variance or similarity measures such as cosine distance in feature embeddings. Aesthetic quality applies to compositional harmony, balancing colors and visual coherence and is measured by usually, using computational models which have been trained on aesthetic datasets or human rating standards. Emotional resonance assesses the emotional reaction of AI-generated art, based on sentiment analysis, physiological or subjective perception scale. On top of these, conceptual depth and deliberate intent or perceived meaning of an artwork are vital in the human-oriented evaluation of creativity.

3.3. Experimental setup and evaluation protocol

The methodological rigor, reproducibility, and balanced representation of neural models used to assess artistic creativity of the experimental setup are determined. GANs, diffusion models, transformers are chosen as the three main types of models as they have different generative processes and possibilities as artistic instruments. It is important to note that each of the models is fine-tuned or trained with curated datasets that represent diverse artistic styles, visual motifs, and multimodal compositions in order to stimulate creative diversity. The assessment plan is based on a two steps model: quantitative and qualitative review. During the quantitative phase, the values of Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Inception Score (IS) and diversity indices are calculated to measure originality, consistency and variability. Also, embedding-based similarity and entropy values determine novelty and content dispersion between samples generated. The qualitative stage involves the involvement of human assessors, such as art experts, cognitive scientists and average audiences to determine the emotional resonance, conceptual richness, and aesthetic values.

4. Quantitative Evaluation Framework

4.1. Objective metrics for measuring originality and diversity

The quantitative assessment of artistic creativity is based on objective measures to measure originality, diversity, and aesthetic coherence in the outputs of AI. The originality can be defined as the level of deviation between current patterns or data distributions whereas diversity is the variation in generated samples. In order to measure these features, such computational measures as the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Inception Score (IS) are commonly used. In a feature space, FID measures similarity between generated and real data distributions, which provides a measure of novelty and realism, and IS measures the differentiation and diversity of the outputs of the classes. Also, feature-space entropy measures and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) can be used to measure perceptual uniqueness and change across the generated artifacts. Embedding-based metrics such as CLIP similarity, used in the case of multimodal tasks, quantify semantic alignment between visual and textual fields in such a way as to retain the coherence without impairing creative variance. In addition to visual analysis, research in computational creativity is more frequently using latent space exploration - the study of how models search through abstract creative spaces throughout generation. Statistical measures like intra-class variance and pairwise dissimilarity are also other means of measuring the dispersion and uniqueness of the artistic products.

4.2. Statistical methods and performance benchmarks

The empirical basis of assessment of the creative performance of neural models is given by the statistical analysis. After the calculation of quantitative indicators including FID, IS, and LPIPS, statistical tools are used to compare performances in architectures and evaluate the relevance of the observed discrepancies. Such techniques as Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), t-tests, and correlation analysis are used to decide whether the differences in measurements of creativity are significant or just accidental. Benchmarking refers to the setting of baseline data sets and standardized test platforms in order to have fair comparison between the models. Open-source tasks such as WikiArt, BAM ( Behance Artistic Media ), and multimodal tasks such as LAION-5B are all varied in terms of the data used to train and to assess. To obtain fair evaluation, generative samples are generated with equalized parameter values- matching resolution, sample size and prompt structure of the input. The performance benchmarks are not only limited to the raw scores, the analysis of trends is also involved, that is, the creative level depends on the complexity of a model, the length of training, and the diversity of data. Regression models and principal component analysis (PCA) can also be used towards determining latent associations between aesthetical quality and structural factors in the models.

4.3. Comparison across different neural architectures

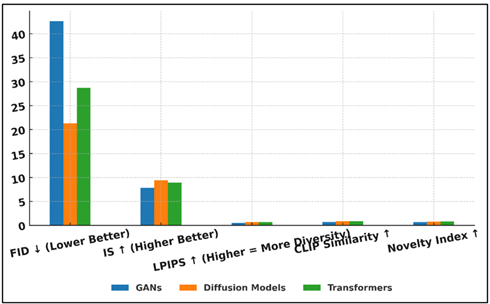

Comparative study of neural architecture: GANs, diffusion models, and transformers provides relevant information on the way different generative processes impact artistic creativity. Both architectures represent a different trade-off between the structure, stochasticity and interpretability, resulting in distinct creative products and expressive capabilities. GANs are also very effective at high-fidelity image generation with stylistic diversity, but tend to be unstable and unable to vary the modes, which may be a drawback. Their adversarial conditioning encourages fine-grained reality but in certain cases, it limits conceptual novelty. Diffusion models, in their turn, excel at coherence and detail through the application of iterative denoising, allowing it to be fine-tuned to the creation and control of composition and aesthetics. Their probabilistic model increases creativity and reproducibility, which are the most suitable in guided art generation. Figure 2 demonstrates that neural structures that evaluate creativity in art have their evaluation flow. By using contextual knowledge, gained with the help of the self-attention mechanism, transformers show impressive flexibility in a variety of modalities, as they can be used to create not just images but also poetry, music, cross-domain art, etc. They are more semantically aligned and conceptually deep and tend to result in outputs with a narrative or emotional level of consistency.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Evaluation Flow of Neural Architectures in Artistic

Creativity Assessment

Comparative evaluation involves using standardized prompts, same datasets and common quantitative metrics (FID, IS, LPIPS) so as to be fair. The analysis of the results is carried out by means of statistical techniques to determine the most sufficient architecture that can find the balance between novelty, coherence, and emotional resonance.

5. Qualitative Evaluation Framework

5.1. Human-centered evaluation through expert judgment and crowd-sourcing

Evaluation should be human-centered, and this is necessary to evaluate the subjective aspects of artistic creativity that cannot be measured by computational means. Because creativity is a personal interpretation, emotion-based, and cultural phenomenon, human evaluators can give subtle details on perceptions of AI-generated art. The strategy usually involves the blending of expert judgment of artists, critics, and scholars with crowd-sourced opinions that reflect a wider opinion of the general population. Critics evaluate works of art according to the set standards of aesthetic value like composition, novelty, sensitivity and conceptual wholeness. They frequently base their appraisals on information related to the domain, providing an analytical critique on the technique and symbolism of art. The phenomenon of crowd-sourced evaluations, collected via such platforms as Amazon Mechanical Turk or online survey, adds additional information to the expertise analysis as it represents a variety of real-world opinions. The participants use aesthetic appeal, emotional resonance, and perceived creativity scale to rate the art created by AI. To deal with the issue of reliability, the inter-rater agreement and consistency tests (e.g., Cronbach alpha, Cohen kappa) are used to evaluate consistency of subjective judgments.

5.2. Cognitive and psychological dimensions of perceived creativity

To comprehend the ways in which individuals think of AI-created art, it is necessary to study the cognitive and psychological mechanisms that guide the interpretation and appreciation. Not only the perception of novelty is connected with creativity, but also with the perception of the work of art in terms of emotional and cognitive association. The most significant focus of cognitive science is to note that human appreciation of creativity deals with processes like pattern recognition, emotional appraisal and making sense that are processes that convert sensory input into subjective aesthetic experience. Theorists such as Arousal Theory by Berlyne and Cognitive Economy Model by Martindale give the psychological grounds about the best levels of novelty and complexity to trigger positive affective reaction. Too much randomness may be confusing, whereas moderate unpredictability will keep one entertained and intrigued. Such principles play an essential role in assessing AI-generated art since they help explain why some of them seem more creative than others despite their similar technical parameters. The cognitive processes of AI art are investigated with the help of empirical research methods such as eye-tracking, emotion recognition, and semantic association tasks. Self-reports or the physiological measurement of emotional resonance through heart rate variability and galvanic skin response can also measure emotional resonance.

6. Results and Analysis

The analysis showed that neural structures possessed unique creative traits. GANs were highly aesthetic and low in concept novelty because of adversarial constraints. Diffusion models had a higher coherence, detail, and diversity and were more successful in regulated artistic expression. Transformers were the most semantically and emotionally creative, and generated context-rich and conceptually stratified outputs. Human-based assessments were in line with computational scales with emotional resonance and interpretive depth being the main determinists of perceived creativity.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative Evaluation Metrics for Neural Models |

|||||

|

Model Type |

FID ↓ (Lower Better) |

IS ↑ (Higher Better) |

LPIPS ↑ (Higher = More Diversity) |

CLIP Similarity ↑ |

Novelty Index ↑ |

|

GANs |

42.6 |

7.8 |

0.51 |

0.72 |

0.64 |

|

Diffusion Models |

21.3 |

9.4 |

0.68 |

0.83 |

0.79 |

|

Transformers |

28.7 |

8.9 |

0.63 |

0.88 |

0.82 |

The numeric findings in Table 2 indicate that there are obvious differences in creative abilities of various neural structures. The lowest Fréchet Inception Distance was of diffusion models (FID = 21.3), which means the most realistic and coherent generated outputs. The fact that they have a high Inception Score (IS = 9.4) and LPIPS (0.68) also means that they are better in diversity and aesthetic quality due to their iterative denoising and their probabilistic nature. Figure 3 indicates relative analysis of the generative models in terms of quality, diversity. Transformers outperformed diffusion models on the similarity of Clip (0.88 and 0.82) and Novelty Index (0.82), indicating a good semantic comprehension and conceptual imaginations.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Evaluation of Generative Model

Performance Across Quality and Diversity Metrics

These findings indicate that transformers are effective at matching the visual or textual input with meaningful context, and generate outputs that have a narrative or emotive character. Despite their central role in generative art, GANs achieved higher FID (42.6) and reduced diversity, which implies that no novelty is generated by them because of the limitations of adversarial training and possible mode collapse.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Qualitative Human Evaluation Scores (Mean Ratings: 1–10 Scale) |

|||

|

Evaluation Criteria |

GANs |

Diffusion Models |

Transformers |

|

Aesthetic Appeal |

8.1 |

9.2 |

8.8 |

|

Originality / Novelty |

7 |

8.6 |

9.1 |

|

Emotional Resonance |

6.8 |

8.3 |

9.4 |

|

Conceptual Depth |

6.5 |

8 |

9.5 |

|

Overall Perceived Creativity |

7.1 |

8.8 |

9.3 |

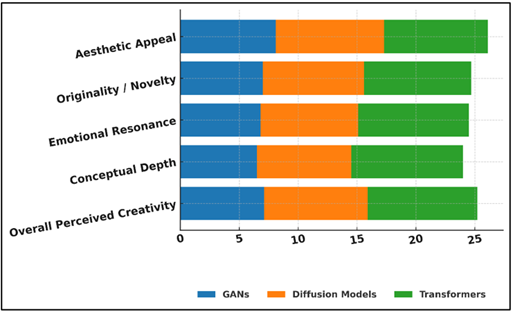

The qualitative human analysis findings confirm the presence of perceptual and emotional variations in the ratings of the creativity of audiences and experts in the neural models Table 3. Aesthetic Appeal (9.2) was the highest rated and diffusion models are capable of creating harmony and detailed images. Their work was frequently said to be balanced, realistic and stylistically interesting. Transformers, on the other hand, performed better in the higher levels of creativity, getting the highest marks in Originality (9.1), Emotional Resonance (9.4), and Conceptual Depth (9.5). Figure 4 reveals some of the comparative creative characteristics of different generative AI models. This implies that they are strong in creating semantically-filled, emotionally creative, and contextually-integrated art forms that are appealing to human interpretations.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Creative Attributes Across Generative AI Models

Transformers create more interpretive and affective outputs by tapping into the linguistic and multimodal knowledge of bridging the narrative meaning and artistic form. Although GANs received high scores on visual realism (Aesthetic Appeal = 8.1), they scored low on perceived originality and emotionality as a result of repetitive image patterns and a lack of conceptual diversity.

7. Conclusion

This paper has discussed the artistic creativity as assessed using neural models, and has taken quantitative measures, qualitative measures, and cognitive viewpoints to form an analytic whole. The study shedding light on GANs, diffusion models, and transformers, these research designs demonstrated how more distinct neural architectures diversely represent creativity. At the same time, GANs were not very creative and limited in repetitive patterns and adversarial optimization restrictions, although they performed well in creating visually appealing and stylish output. The iterative denoising and probabilistic structure of diffusion models was observed to have better diversity and detail and was more stable, and generated more outputs consistent with novelty alongside aesthetic harmony. The extension of the concept of creativity to multimodal expression was carried out through the contextual and semantic reasoning abilities of transformers which had promoted creative thought to visual contexts. The fact that they could combine text, image, and sound enabled them to synthesize it meaningfully across a cross-modal middle ground to inspire stronger emotional and narrative responses. Quantitative indicators like FID, IS and LPIPS provided objective tools of originality and diversity and the qualitative measures by experts and crowd-sourced participants were used to give an insight into emotional resonance and meaning perception. The results highlight the fact that AI creativity cannot be represented by a set of numbers only, it is manifested at the crossroads of algorithmic innovation and human perception. The difficulty with neural models as they are developed is the need to come up with evaluation frameworks that can take into consideration cultural, psychological and contextual peculiarities.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Brauwers, G., and Frasincar, F. (2021). A General Survey on Attention Mechanisms in Deep Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 35, 3279–3298. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2021.3126456

Cheng, M. (2022). The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art. Proceedings, 81, Article 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022081110

Guo, D. H., Chen, H. X., Wu, R. L., and Wang, Y. G. (2023). AIGC Challenges and Opportunities Related to Public Safety: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 4, 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.08.001

Hafiz, A. M., Parah, S. A., and Bhat, R. U. A. (2021). Attention Mechanisms and Deep Learning for Machine Vision: A Survey of the State of the Art. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-510910/v1

Leong, W. Y., and Zhang, J. B. (2025). AI on Academic Integrity and Plagiarism Detection. ASM Science Journal, 20, Article 75. https://doi.org/10.32802/asmscj.2025.1918

Leong, W. Y., and Zhang, J. B. (2025). Ethical Design of AI for Education and Learning Systems. ASM Science Journal, 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.32802/asmscj.2025.1917

Liu, Y., Shao, Z., and Hoffmann, N. (2021). Global Attention Mechanism: Retain Information to Enhance Channel-Spatial Interactions. arXiv (arXiv:2112.05561). https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.05561

Lou, Y. Q. (2023). Human creativity in the AIGC era. Journal of Design Economics and Innovation, 9, 541–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2024.02.002

Niu, Z., Zhong, G., and Yu, H. (2021). A Review on the Attention Mechanism of Deep Learning. Neurocomputing, 452, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.03.091

Oksanen, A., Cvetkovic, A., Akin, N., Latikka, R., Bergdahl, J., Chen, Y., and Savela, N. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in Fine Arts: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1, Article 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2023.100004

Png, W. H., Aun, Y., and Gan, M. (2024). FeaST: Feature-Guided Style Transfer for High-Fidelity Art Synthesis. Computers and Graphics, 122, Article 103975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2024.103975

Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., and Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents. arXiv (2204.06125).

Shao, L. J., Chen, B. S., Zhang, Z. Q., Zhang, Z., and Chen, X. R. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) in Medicine: A Narrative Review. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 21(2), 1672–1711. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2024073

Xu, J., Zhang, X., Li, H., Yoo, C., and Pan, Y. (2023). Is Everyone an Artist? A Study on User Experience of AI-Based Painting System. Applied Sciences, 13, Article 6496. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116496

Xu, X. (2024). A Fuzzy Control Algorithm Based on Artificial Intelligence for the Fusion of Traditional Chinese Painting and AI Painting. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 17846. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68375-x

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.