ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Emotion-Aware Tutoring Systems for Performing Arts

Dr. Jairam Poudwal

1![]()

![]() ,

Praney Madan 2

,

Praney Madan 2![]()

![]() , Sadhana Sargam 3

, Sadhana Sargam 3![]() , Torana Kamble 4

, Torana Kamble 4![]() , Ayaan Faiz 5

, Ayaan Faiz 5![]()

![]() , Dr. Dhirendra Nath Thatoi 6

, Dr. Dhirendra Nath Thatoi 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Fine Art, Parul Institute of Fine Arts, Parul

University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

2 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of

Business Management, Noida International University, Greater Noida, Uttar

Pradesh, India

4 Bharati Vidyapeeth College of

Engineering, Navi Mumbai, Mumbai University, Maharashtra, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Professor, Department of Mechanical

Engineering, Institute of Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Digital

performing arts education Emotion-aware tutoring systems are a new

development in the field of digital performing arts, which combines the

concept of affective computing with multimodal learning analytics to improve

the growth of expressive skills. Conventional online training systems have

been emphasizing more on technical accuracy pitch

accuracy, movement accuracy or dialogue accuracy but have failed to consider

the emotional shades required in artistic excellence. The current research

introduces and analyzes an AI-based framework that helps to capture emotional

stimuli based on face expression analysis, voice prosody analysis, gesture

monitoring, and movement patterns. The system is capable of

detecting emotional deviations, feedback provision, and helping the

learner understand themselves by three examples in dance, theatre, and vocal

music. The quantitative data reveals that there are large improvements in the

emotional accuracy (32-40%), expressive clarity, and performance coherence in

all domains. Adaptive feedback mechanism in the system leads to increased

engagement and elevation of emotional literacy where learners can tune the

emotions and the expressive behavior. The results reveal the significance of

incorporating emotion-sensitive technologies into the arts pedagogy and

emphasize the importance of the hybrid human-AI co-learning models in the

process of balancing between technical instructions and creative autonomy.

The ethical concerns, such as emotional privacy, cultural difference,

and algorithmic prejudice are addressed to make sure that there is

responsible execution. In general, the paper shows that emotion-sensitive

tutoring systems can provide a revolutionary method of performing arts

education, enhancing more expressive growth, and overcome the traditional

disadvantages of teaching digital arts in a digital setting. |

|||

|

Received 09 February 2025 Accepted 01 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Jairam Poudwal, director.pifa@paruluniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6746 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Emotion-Aware Tutoring, Affective Computing,

Multimodal Emotion Recognition, Dance Emotion Coaching, Theatre Dialogue

Correction, Vocal Expressivity Assessment, Emotional Accuracy, Creative

Pedagogy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Introduction to Emotion in Performing Arts Education

The core of performing arts is emotion, which determines the meaning and the influence of a creative expression. In dance, theatre, or music, emotional authenticity allows performers to convey meaning and raise responses in the audience and to express more sophisticated psychological states. Education of the performing arts is thus more than technical mastery, it involves the emotional intelligence, expressiveness embodied, and the ability to express the inner experiences in movement, voice, and gesture. Traditionally, the development of emotional training has been modeled on the basis of mentorship, during which teachers teach learners on how to express themselves, through demonstrating expressive techniques, giving verbal feedback and evoking imaginative triggers Khare et al. (2024). Nevertheless, emotional expression is subjective, and it is very much individualized, and therefore, it is not consistent in evaluation, and it is mostly limited to the expertise of the instructor. The growing digitalization of arts education the pace of which has been increased by the world remote-learning demands has brought to light critical distances in achieving emotional complexity with the help of online platforms. Conventional digital instruments are more focused on ensuring precision in the intonation, time, or the movement rather than the more nuanced affective plane of artistic development Mohana and Subashini (2024). The recent progress of affective computing, multimodal sensing, and machine learning presents new opportunities of implementing emotional analysis in digital tutoring setting. Emotion-sensitive tutoring systems seek to mediate between the cognitive and affective aspects of artistic training to establish emotional cues with the help of facial expressions, the voice, gesture relations, and physiological indicators. Such systems are capable of delivering real-time, data-based information about emotional sincerity and assist students to perfect the expressive nuances Gursesli et al. (2024). Emotional intelligence application to digital pedagogy serves the whole-person development of skills, promotes creativity among learners, and makes artistic education in the distance as effective and valuable as possible. Since performing arts are now adopting hybrid and virtual learning platforms, emotion-sensitive systems are an important development in the facilitation of expressive excellence Elsheikh et al. (2024).

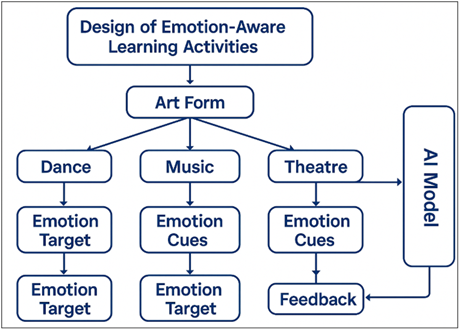

Figure 1

Figure 1 Block design of Emotion-Aware Learning System

Traditional models of performing arts education are based on the personal mentor, peer-based learning, and the cyclical rehearsals. Although these techniques are highly interactive among humans, they have major constraints, particularly in the contemporary digital world of learning Canal et al. (2022). To begin with, emotional feedback is pretty much subjective, and it differs among instructors basing on their respective personal style, experience, and interpretive frameworks as indicated in Figure 1. This inconsistency restricts uniformity and can mislead learners especially when they are at the initial level of acquiring skills. Conventional tests are technical, centered on such issues as alignment, timing, or vocal accuracy and emotional expressivity is not always measured but is judged either by impression or not at all. Second, personalized emotional guidance is limited in terms of the scope of its scalability Trinh Van et al. (2022). Emotional coaching becomes challenging in the large group rehearsal or classroom because an instructor cannot be able to observe many students at a time. Third, the transition to online training undermined key elements of expressive training. Bidimensional displays minimize view of minor body language, micro-expressions, and gesture. Sound compression may alter the voice tone, influencing feedback on the expression. Fourth, students usually have difficulties with self-evaluation. Lack of constant feedback can make them misread emotional signals, do exaggerated or toned down gestures, or lose the ability to synchronize an internal state and an external act. Fifth, there are psychological barrier like performance anxiety that are more difficult to trace remotely Ahmed et al. (2019). The conventional systems do not contain the means of identifying signs of stress or emotional exhaustion that affect the quality of performance. Lastly, most learning programs consider performing arts to be more of a technical discipline, disregarding the emotional aspect of authenticity to creativity. These constraints have highlighted the importance of emotion sensitive digital spaces that have the ability to deliver sensitive, stable, and adaptive instructions in expressive skill building Wu et al. (2022).

2. Emotion-Centric Learning Theories and Artistic Cognition

Learning theories that prioritize emotions emphasize the key role of affect in artistic cognition, creativity and embodied performance. Constructivist approaches suggest that learners can internalize emotional knowledge by engaging in active way, imitating, reflecting and embodied simulation. In his theories, Vygotsky focuses on the emotional significance creation based on social and cultural mediation, and guided emotional experiences play a significant role in the development of art. In performing arts, emotions are not the states of mind but manifested objects that are represented in the form of correlated vocal, facial, and body behaviors Elansary et al. (2024). Other approaches to melding emotional intent and expressive means, as shown in the theories of Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), the System of Stanislavski, and Dalcroze Eurhythmics, show systematic methods of relating the intention to expressive means. Neuroscientific surveys also indicate that emotional expression is associated with the coordinated activation of motor, sensory as well as affective networks in the brain. Such insights stipulate that emotional learning involves holistic, cognitive, and physical learning. The emotional memory, empathy, and affective perspective-taking also play a role in the capacity of a performer to decipher characters, narratives and musical phrasing Försterling et al. (2024). Embodied cognition theories propose that emotions are performed by dynamic movement patterns, muscular tension and as a result, physicality is a prerequisite of emotional genuineness. Educators of arts education believe that the arts can be better learnt when students become emotionally literate: knowing how to use emotions to change timing, rhythm, flow of movement and vocal timbre Mousavinasab et al. (2021). Emotionalistic methods to acknowledge the cyclic association between inner emotional condition and external artistic manifestation. When students learn about the effects of emotions on the physiological reactions, their expressive ability and imaginative explanation becomes better. These conceptual grounds are the decisions to incorporate emotional analytics into tutoring systems that allow technology to contribute to the formation of emotional awareness, expressive coordination, and artistic cognition Hasan et al. (2020).

3. Emotion Recognition Tools for Creative Learning

Emotion-aware tutoring systems of performing arts are based on emotion recognition tools. These sensors utilize high-level AI models and multisensory sensors to identify the emotional state in a visual, auditory, and physiological channel. Emotion detectors are based on computer vision, which analyzes facial expressions to identify happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise and calmness. The methods such as CNNs, Vision Transformers, and landmark detection models do capture minute micro-expressions and relate muscle movements of the face to a specific emotion. Emotion recognition systems are voice-based systems that use vocal timbre, pitch, energy, rhythm and spectral signature to determine the affective nature in speech or singing.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparison of Multimodal Emotion Recognition Modalities |

||||

|

Modality |

Sensor/Input

Type |

Key

Emotional Features Extracted |

Common

AI Models Used |

Application

in Creative Learning |

|

Facial

Expression Hasan et al. (2020) |

Webcam

/ RGB Camera |

AU

(Action Units), micro-expressions, gaze |

CNN,

Vision Transformer, FaceNet |

Acting/monologue

emotional accuracy |

|

Vocal Emotion Anwar et al. (2022) |

Microphone |

Pitch, timbre, energy,

rhythm, prosody |

LSTM, Wav2Vec2, Attention

models |

Vocal expressivity, theatre

dialogue |

|

Body

Movement Alshaikh et al. (2020) |

Pose

estimation (OpenPose/MediaPipe) |

Joint

angles, gesture amplitude, flow, weight |

Graph

Neural Nets, LSTM |

Dance

emotion evaluation |

|

Physiological Signals Sun et al. (2023) |

HRV, GSR, smart sensors |

Stress, arousal, cognitive

load |

SVM, Random Forest, Deep

multimodal models |

Anxiety monitoring for

performers |

The variations in the tone of emotion can be identified with the help of audio feature extraction techniques, such as MFCCs, spectrograms, and attention-based acoustic models. In movement-based arts such as dance, pose estimation, such as OpenPose or Media Pipe, is used to estimate pose positions, energy, and pattern of the movement to measure emotional qualities such as tension, fluidity or expansiveness. Physiological instruments, including smartwatches, EDA, and HRV devices, record the internal emotional indicators, stress, or excitement. Such multimodal tools may be combined using fusion networks to form an overall picture of an emotional profile of a performer. The use of emotion recognition technologies makes creative learning richer by allowing an objective analysis of emotional presentation, allowing students to visualize emotions paths, and detecting discrepancies between planned and expressed emotions. Their combination makes sure that the digital learning platforms allow expressive nuances that are a part of artistic mastery.

4. Design of Emotion-Aware Learning Activities (Dance, Music, Theatre)

Emotion-mindful learning practices combine emotional perception and creative work in the fields of dance, music, and theatre. In dance education activities might include acting out certain feelings such as joy, fear, anger, serenity, and the system measures the qualities of movements such as energy, weight, flow, and reach of space to assess the authenticity of expressiveness. Feedback may point out the fact that gestures are too mechanical or that the movement is not emotional enough. Vocal or instrumental exercises in music training can be accompanied by emotional goals, like the expression of melancholy by phrasing or it can be the expression of exaltation by tempo and articulation Al-Fraihat et al. (2020). Emotion cognizant systems examine the tonality of the voice or the dynamics of music to make sure that students match the technical performance with the emotional interpretation. Learning activities in the theatre could be monologue practices, playing with emotions as an actor, or a delivery of dialogues with different affective sounds. Facial expressions, vocal resonance and gesture openness are tracked by the systems to determine the depth of acting. Multi-activity modules enable the learners to explore emotional transitions - between softness and anger or anxiety to confidence and get feedback on smoothness, believability and coherence. Activities that are emotion conscious contribute to emotional literacy, which enables the learners to internalize emotional concepts and reflect them in their performances Bermudez-Edo et al. (2016). These learning designs facilitate creativity, self-awareness and expressive control.

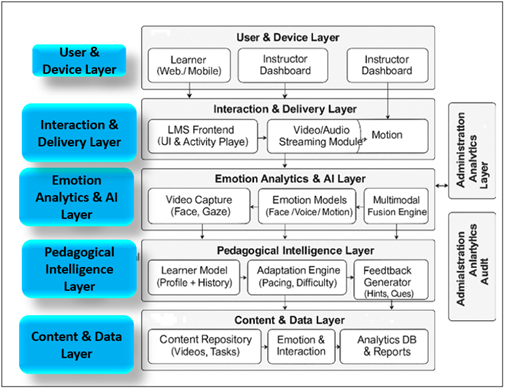

Figure 2

Figure 2 Emotion-Aware E-Learning Platform Architecture

An emotional expressivity evaluation framework should be multidimensional with regard to the multidimensionality of emotion in performing arts. Emotion-sensitive systems are capable of applying quantitative and qualitative evaluation elements. The quantitative measurements are emotional alignment scores, movement expressivity indices, vocal affect accuracy and emotional consistency measures. These scores are produced using multimodal data through mapping identified emotional articulations onto anticipated emotional intention as shown in Figure 2. Qualitative feedback is concerned with subjective elements including emotional genuineness, consistency in movement and facial expression, narrative interpretation and creative subtlety. Rubrics can take into account such criteria as emotional plausibility, richness of description, transition clarity and emotional fantasy. Reflective elements can also be implemented to the assessment systems where learners are required to critically evaluate emotive decisions and explain their interpretations. Emotion trajectory graphs can be used to visualize the effect of emotional intensity throughout a performance. Peer and instructor reviews are the complements of AI assessment since they offer cultural and artistic interpretation. The framework combines performance data, emotional targets, expressive accuracy and interpretive quality in developing a comprehensive evaluation strategy that aids in artistic development. Tutoring systems that are emotion sensitive have a profound effect on student experience because they provide a positive and individualized learning environment. Live emotional feedback enhances self-awareness and makes learners realize how emotions determine the expression of art. Students claim that they feel more motivated with the immediate progress and the ability to see the progress clearly. Emotion-sensitive feedback will decrease the performance anxiety through detecting the indicators of stress early and modifying the guidance response to decrease the cognitive load. Social interaction enhances because students feel emotionally empathized and innovatively pushed. The autonomous learning can also be supported by emotion-aware systems where students can provide themselves with learning experience, yet with emotionally-relevant feedback. In the case of remote learners, the system helps the learners to receive equal compensation due to the lack of face-to-face emotional guidance so that virtual rehearsals are expressive and meaningful. These systems create confidence, determination, and a stronger connection to the art form by focusing on emotional and psychological aspects of it. Altogether, emotion-sensitive tutoring has a positive effect on the well-being of students and helps to make the performing arts education more holistic.

5. Case Studies

Emotion-sensitive feedback will decrease the performance anxiety through detecting the indicators of stress early and modifying the guidance response to decrease the cognitive load. Social interaction enhances because students feel emotionally empathized and innovatively pushed. The autonomous learning can also be supported by emotion-aware systems where students can provide themselves with learning experience, yet with emotionally-relevant feedback. In the case of remote learners, the system helps the learners to receive equal compensation due to the lack of face-to-face emotional guidance so that virtual rehearsals are expressive and meaningful. These systems create confidence, determination, and a stronger connection to the art form by focusing on emotional and psychological aspects of it. Altogether, emotion-sensitive tutoring has a positive effect on the well-being of students and helps to make the performing arts education more holistic.

5.1. Case Study 1: Dance Emotion Coaching

The case study focuses on the impact of an emotional tutoring system to improve expressive performance in contemporary dance. This group has included 18 middle-level dancers who took part in a six-week module that involved transferring four fundamental commodities of emotions, namely joy, sadness, anger, and serenity, using sequences of choreographed dances. It utilized the system of video-based pose estimation (e.g., Media Pipe), facial micro-expression analysis and gesture-intensity mapping to assess the real-time emotional expressiveness of dancers.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Sample Dataset for Dance Emotion Coaching |

||||||

|

Dancer

ID |

Target

Emotion |

Movement

Energy Score (0–1) |

Flow

Smoothness (0–1) |

Facial

Emotion Accuracy (%) |

Gesture

Expansion (cm) |

System

Alignment Score (%) |

|

D01 |

Joy |

0.82 |

0.91 |

78 |

142 |

81 |

|

D02 |

Anger |

0.76 |

0.69 |

65 |

175 |

72 |

|

D03 |

Sadness |

0.41 |

0.57 |

69 |

88 |

66 |

|

D04 |

Serenity |

0.53 |

0.88 |

72 |

95 |

78 |

|

D05 |

Anger |

0.88 |

0.64 |

84 |

182 |

89 |

|

D06 |

Joy |

0.79 |

0.87 |

75 |

138 |

80 |

During the Week 1, the baseline testing indicated that the expressive balance was common in that dancers were inclined to do either over- or under-perform emotions through exaggerated gestures or limited body movement, respectively, and display inconsistency in emotions. As an example, sadness could be expressed using demonstratively excessively theatrical movements, whereas anger did not have enough muscular tension and directionality. The system detected these discrepancies through the measurement of energy expenditure, movement flow, openness of gestures as well as micro-expressions. It would then display specific feedback in the form of visual overlays in which emotional clarity needed to be refined. Weeks 2-4 Dancers participated in emotion-specific coaching sessions. In the case of joy, the system stimulated the enhancement of upward movement patterns, fluid weight changing, and facial openness. In the case of anger, the feedback focused on increased core involvement, directional movements and more definite tempo. This multimodal feedback assisted the dancers in internalizing the way the physical dynamics influence the quality of emotions. It was found, based on qualitative interviews, that the learners were more enlightened to the role of tension, space and breath in bringing out emotional authenticity. Week 6, the emotional accuracy, as indicated by system alignment scores, got improved; the average increase was 32 with the highest increase in the anger and serenity as the two emotions that are traditionally hard to describe clearly. The professional assessors wrote that dancers were more competent in the transitions of emotions and more congruent in the quality of movement with facial expression. Students said they had more confidence, emotional comprehension, and ability to control expressive articulation. As shown in the case study, emotion-conscious coaching helps dancers to attain a complex emotional literacy between technical accuracy and expressiveness.

5.2. Case Study 2: Theatre Dialogue Emotion Correction

This case study discusses how an emotion aware system can be used to facilitate emotional accuracy in spoken theatre dialogue. The system evaluated the facial expressions, voice tone, prosody, and micro-gestures, which aided in identifying emotional deviations of the intended affect of the script, over a four-week period of rehearsing monologues and dialogue snippets by twelve theatre students.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Sample Dataset for Theatre Dialogue Emotion Correction |

||||||

|

Actor

ID |

Dialogue

Emotion |

Vocal

Prosody Match (%) |

Pitch

Variation (Hz) |

Facial

Expression Match (%) |

Emotion

Deviation Score (0–1) |

Final

Delivery Quality (%) |

|

A01 |

Fear |

62 |

27 |

69 |

0.38 |

74 |

|

A02 |

Anger |

71 |

32 |

81 |

0.26 |

85 |

|

A03 |

Sadness |

54 |

14 |

63 |

0.47 |

67 |

|

A04 |

Triumph |

83 |

45 |

88 |

0.18 |

91 |

|

A05 |

Suppressed

Anger |

58 |

21 |

72 |

0.41 |

76 |

|

A06 |

Anxiety |

66 |

25 |

70 |

0.33 |

80 |

The pre-test results indicated that the students often mismatched the tone of emotion with the text. As an illustration, the words that needed suppressed anger were intonated in a flat tone, whereas there was no voice tremble or body contraction in the situations where one was supposed to be afraid. These inconsistencies in the system were identified using spectrogram patterns, changes in prosodies and real-time expression vectors. Emotional mismatch score made the learners realize where their performance fell short of the emotional goal of the character. The system provided accurate corrections during the rehearsal cycles. An example is that in case a learner gave a fearful line with inadequate vocal instability, the system recommended more tension in breathing and slight tonal variation. The system showed the facial-muscle activation maps of undervalued expressions when frustration was supposed to be shown but sadness was identified. Students were able to listen to their recordings in comparison with ideal expressive models so that they could see the differences between the intended and the actual expression. At Week 4, there were changes in the accuracy of vocal emotions (average increased by 27%) and facial congruence with dialogue (increased by 31%). Students claimed that visual emotional signs assisted them to identify unconscious expressive patterns as simply smiling in moments of tension or keeping eye contact neutral during moments of emotional intensity. Additionally, the instructors observed that AI generated emotional responses shortened the time spent in rehearsal as students would correct themselves first before receiving the instructor feedback. The case study demonstrates the potential of emotion-sensitive systems to be effective partners of theatrical pedagogy, by allowing more sophisticated interpretation of characters and enhancing the emotional credibility of actors in dramatic acting.

5.3. Case Study 3: Music Vocal Expressivity Improvement

Emotion-conscious AI in music performance expressive training is the third case study. A total of sixteen singers were enrolled in an eight-week course that aimed at enhancing emotional coloring, phrasing, and tonal warmth and expressiveness. The system evaluated the following vocal components; pitch contour, timbre, vibrato, breathiness and intensity as well as facial and postural expression.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Sample Dataset for Music Vocal Expressivity |

||||||

|

Singer

ID |

Emotion

Category |

Timbre

Warmth (0–1) |

Vibrato

Rate (Hz) |

Dynamic

Range (dB) |

Spectral

Brightness (%) |

Emotional

Accuracy (%) |

|

S01 |

Melancholy |

0.61 |

4.8 |

18 |

42 |

73 |

|

S02 |

Joy |

0.78 |

6.1 |

30 |

67 |

88 |

|

S03 |

Longing |

0.69 |

5.4 |

23 |

51 |

81 |

|

S04 |

Excitement |

0.83 |

6.9 |

35 |

72 |

92 |

|

S05 |

Serenity |

0.58 |

4.3 |

16 |

39 |

70 |

|

S06 |

Triumph |

0.76 |

6.4 |

28 |

65 |

86 |

The initial recording showed that there was a significant expressive problem, namely, students tended to be technically perfect in their pitch but could not convey deeper emotions. Songs with a label of melancholic, such as, were sung with correct notes but lack of tone darkening or phrasing variation. On the contrary, overly bright tones in the performances were used without rhythmic elasticity. The system measured such deviations in terms of emotional acoustic profiles and projected them to desired emotion models. The system indicated the inconsistencies of emotions, noting that the vibrato speed was not high enough in longing passages, or that passages with high energy had to be expanded more energetically. Facial expression recognition also helped to remind singers to coordinate eye attention and facial expression with the emotional tone. Week 8 scores show an increase of 35-40 percent in emotional accuracy scores across all categories. Students showed more tone shading, less emotive disjunctions and more expressive breathing. Specialist vocal coaches acknowledged that the AI system could be helpful in assisting emotional detail with technique without interference. Students stated that emotive analytics were useful to them in seeing the relationship between vocal mechanisms and expressive interpretation, which is less tangible. As established in this case study, emotion-sensitive vocal coaching supplements classic training in enabling singers to master emotional color, dramatic phrasing and natural delivery, which are among the key elements of strong musical performance.

6. Discussion

The results of the three case-studies dance emotion coaching, theatre dialogue emotion correction and vocal expressiveness improvement, prove the transformative nature of emotion-aware tutoring systems in performing arts education. Taken together, the findings help to develop an understanding of the way multimodal affective computing can overcome the pedagogical rift that has persistently existed between the teaching of technical skill and the inculcation of emotional authenticity, which is one of the constituent elements of artistic acting. In every sphere, there were significant improvements in the emotional accuracy, expressiveness, and self-awareness of the learners, which highlights the validity of the real-time, emotion-based feedback. The reported quantitative improvement of the values presented in the tables and graphs such as an average increase in emotional accuracy of 32-40 points indicate that affective AI may be used to systematically improve expressive performance even in short training periods.

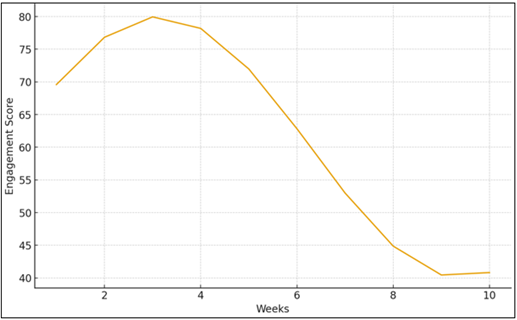

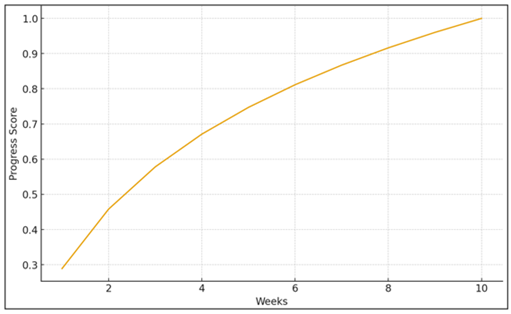

Figure 3

Figure 3 Student Engagement Trends

Figure 3 shows the student engagement variation throughout the training process that is ten weeks. The graph shows that there was a first increase in the engagement within the initial three weeks, which was related to the novelty of the emotion-conscious tutoring system and the early motivation enhancement it brings about. The most active time is the Week 3-4 when learners are fully oriented on the use of real-time emotional feedback tools and can start to notice real changes in their expressive skills. Nevertheless, there is still progressive decreasing effect in the later weeks, as is normal with long-periodic training of the creative, which can be due to cognitive fatigue, augmented complexity of task, or emotional overload. The trend supports the significance of integration of adaptive pacing, periodic fluctuation in learning exercises, and emotional reinforcement methods to maintain interest in the process of long-term performing arts training. The case studies also indicate that multimodal feedback is closely associated with emotional learning whereby, visual, auditory and motion feedback are used to construct a wholesome picture of emotional expression. In dancing, the most improved emotions were anger and serenity, in which learners usually have a problem with maintaining intensity and control. Gesture enhancement, energy transfer and micro-expressions analysis possibilities allowed the system to provide dancers with the possibility to visualize emotional opposition and to perfect physical expression. Through the process, theatre students also were able to advantage on comprehensive indicators of prosody and facial misalignment, which enabled them to rectify expressive habits that had developed unconsciously and place the tone of their emotions in line with dramatic intent. The case of music vocal expressivity demonstrated how the acoustic parameters such as timbre warmth, vibrato shape, spectral brightness, etc., provide a contribution to emotional color during a performance that enables singers to transcend the importance of pitch accuracy to the richer expressiveness resonance. These results contribute to the notion that emotional competence in performing arts cannot be measured in one modality, but instead involves the combination of several expressive dimensions, which AI is sole to analyze.

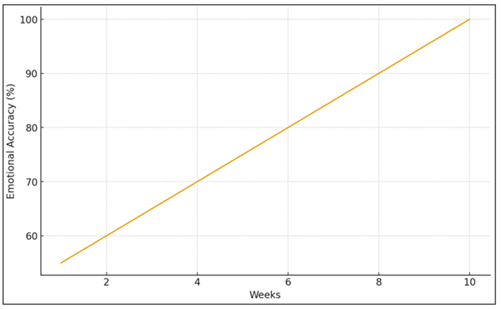

Figure 4

Figure 4 Emotional Accuracy Improvement

Figure 4 shows that the emotional accuracy has a steady increasing trend, which means that the learners would gradually match their expressive performance to the desired emotional goals as the training advances. This gradual increase is indicative of the multimodal affect recognition methods, including the facial analysis, vocal prosody analysis, and gesture-monitored emotion, being useful in creating accurate and immediate feedback. The consecutive flow indicates that the system is effective in eliminating ambiguity in the delivery of emotions and facilitating the students to rectify expressive deviation on a structured basis. The Week 10 comparison with the emotional accuracy levels indicates the importance of affective AI as a potent contributor to the expressive accuracy in the education of performing arts. Although the results are encouraging, the Discussion also reflects the important issues to consider when implementing it. To begin with, even though AI-based feedback contributes to its objectivity and consistency, artistic expression is subjective in nature and culturally rooted and subject to interpretation. Thus emotion conscious systems should be deployed as support systems and not substitutes of human instructors. The model of co-learning suggested in the case studies, when AI furnishes real-time analytics and teachers guide in an interpretive, contextual, and narrative manner, will allow maintaining artistic individuality and at the same time make sure that learners receive accurate feedback. Second, the fluctuation in the engagement patterns throughout training period allows us to believe that emotional learning is cognitively taxing and requires the pacing of training and adaptive feedback mechanisms to maintain motivation. The emotion-sensitive systems should be created in such a way that they identify the fatigue of the learners and make relevant adaptations that prevent burnout.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Training Progress Curve

The normalized training progress score that describes the integrated enhancement of learners in the several expressive dimensions- emotion delivery, timing, posture, movement energy, and vocal tone. The curve takes the typical form of a logarithmic growth curve where the curve starts out soaring but as learners get closer to mastering it, it starts leveling off. The sharp rise during the first weeks proves that emotion-sensitive automated instructions facilitate learning among the beginners by rectifying basic expressive mistakes. The decline in growth rate but gradual increase in the later weeks suggests perfection of more advanced skills and the need of a more subtle emotional and technical regulation. This graph as represented in Figure 5 confirms the effectiveness of the system in the long run whilst highlighting the necessity of differentiated challenges to high learners to ensure a performance plateau is not reached. Ethics is also a factor that comes out during the discourse. Cultural bias of emotion-recognition algorithms, the emotional information being sensitive, and the danger of relying on AI too much all emphasize the importance of designing the systems carefully and basing it on fairness, transparency, and artistic respect. However, the robust gains with learner groups suggest that in situations where it is not abused, emotion-conscious tutoring systems can greatly increase emotional literacy, learning of expressive skills, and democratizing access to high-quality performing art education. In general, the presented work shows that affective AI has a significant potential to transform the future of digital arts education as it allows creating a new paradigm in which emotion, technology, and creativity overlap to enhance artistic education.

7. Conclusion

The study indicates that emotion-conscious tutoring systems have the potential to diversify the process of performing arts education greatly because they can incorporate the aspect of affective intelligence into online educational settings. These systems provide a means to mediate the divide between the technical skill and the emotional depth two pillars needed to achieve the authentic performance of an artistic performance by integrating these three aspects: the ability to recognize facial emotions, the analysis of vocal prosody, and the evaluation of movement by gesture. The case analyses in dance, theatre and vocal music all indicate that the learners are advantaged by the accuracy of their multimodal instructions which contributes to the clarity of emotion, the diminution of expressive discrepancies and the improvement of their general capacity to interpret. Instead of replacing the instructor, the emotional conscious system should be used as a co-creative partner to assist learners in terms of objective emotional analytics without eliminating the artistic uniqueness and cultural specificity. Ethical issues remain very important, especially in regard to sensitivity of emotional data and modeling bias. However, appropriately developed, emotionally intelligent tutoring systems are a paradigm shift, which promises to be scalable, accessible, and more importantly, emotional intelligence that can be utilized to support learners. They are indicative of a day when AIs will be used to have a positive impact on expressive training and provide new possibilities in creative growth of the performing arts education.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, F., Bari, A. H., and Gavrilova, M. L. (2019). Emotion Recognition from Body Movement. IEEE Access, 8, 11761–11781. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2963113

Al-Fraihat, D., Joy, M., Sinclair, J., and Masa'deh, R. (2020). Evaluating E-Learning Systems Success: An Empirical Study. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004

Alshaikh, Z., Tamang, L., and Rus, V. (2020). A Socratic Tutor for Source Code Comprehension. In Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2020) ( 15–19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52240-7_3

Anwar, A., Haq, I. U., Mian, I. A., Shah, F., Alroobaea, R., Hussain, S., Ullah, S. S., and Umar, F. (2022). Applying Real-Time Dynamic Scaffolding Techniques During Tutoring Sessions Using Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Mobile Information Systems, 2022, 6006467. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6006467

Bermudez-Edo, M., Elsaleh, T., Barnaghi, P., and Taylor, K. (2016). IoT-Lite: A Lightweight Semantic Model for the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE UIC/ATC/ScalCom/CBDCom/IoP/SmartWorld (90–97). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/UIC-ATC-ScalCom-CBDCom-IoP-SmartWorld.2016.0035

Canal, F. Z., Müller, T. R., Matias, J. C., Scotton, G. G., de Sá Junior, A. R., Pozzebon, E., and Sobieranski, A. C. (2022). A Survey on Facial Emotion Recognition Techniques: A State-Of-The-Art Literature Review. Information Sciences, 582, 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2021.10.005

Elansary, L., Taha, Z., and Gad, W. (2024). Survey on Emotion Recognition Through Posture Detection and the Possibility of its Application in Virtual Reality. arXiv. arXiv:2408.01728

Elsheikh, R. A., Mohamed, M. A., Abou-Taleb, A. M., and Ata, M. M. (2024). Improved Facial Emotion Recognition Model Based on a Novel Deep Convolutional Structure. Scientific Reports, 14, 29050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79167-8

Försterling, M., Gerdemann, S., Parkinson, B., and Hepach, R. (2024). Exploring the Expression of Emotions in Children's Body Posture Using Openpose. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Gursesli, M. C., Lombardi, S., Duradoni, M., Bocchi, L., Guazzini, A., and Lanata, A. (2024). Facial Emotion Recognition (FER) Through Custom Lightweight CNN Model: Performance Evaluation in Public Datasets. IEEE Access, 12, 45543–45559. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3380847

Hasan, M. A., Noor, N. F. M., Rahman, S. S. B. A., and Rahman, M. M. (2020). The Transition from Intelligent to Affective Tutoring System: A Review and Open Issues. IEEE Access, 8, 204612–204638. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3036990

Khare, S. K., Blanes-Vidal, V., Nadimi, E. S., and Acharya, U. R. (2024). Emotion Recognition and Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review (2014–2023) and Research Recommendations. Information Fusion, 102, 102019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102019

Mohana, M., and Subashini, P. (2024). Facial Expression Recognition using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques: A Systematic Review. SN Computer Science, 5, 432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-024-02792-7

Mousavinasab, E., Zarifsanaiey, N., Niakan Kalhori, S. R., Rakhshan, M., Keikha, L., and Ghazi Saeedi, M. (2021). Intelligent Tutoring Systems: A Systematic Review of Characteristics, Applications, and Evaluation Methods. Interactive Learning Environments, 29, 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1558257

Sun, L., Kangas, M., and Ruokamo, H. (2023). Game-Based Features in Intelligent Game-Based Learning Environments: A Systematic Literature Review. Interactive Learning Environments. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2179638

Trinh Van, L., Dao Thi Le, T., Le Xuan, T., and Castelli, E. (2022). Emotional Speech Recognition Using Deep Neural Networks. Sensors, 22, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22041414

Wu, J., Zhang, Y., Sun, S., Li, Q., and Zhao, X. (2022). Generalized Zero-Shot Emotion Recognition from Body Gestures. Applied Intelligence, 52, 8616–8634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-021-02927-w

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.