ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Data Science for Measuring Visual Influence in Art

Nittin Sharma 1![]()

![]() ,

Mona Sharma 2

,

Mona Sharma 2![]() , Dr. Pratik Mungekar 3

, Dr. Pratik Mungekar 3![]() , Aswathy N Rajan 4

, Aswathy N Rajan 4![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Omprakash Das 5

,

Dr. Omprakash Das 5![]()

![]() ,

Shivam Khurana 6

,

Shivam Khurana 6![]()

![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International University,

Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Director, Research Innovation and Internationalization, Sharda

Education Society Thane, Affiliated to University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

5 Assistant Professor, Centre for Internet of Things, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan

(Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper

discusses the applications of data-driven approaches to quantify visual

influence in art which combines computational means with art-historical

theory to identify stylistic and conceptual connections between artists and

works of art. The paper investigates the way data science can give objective

schemes of the artistic evolution by quantifying the visual similarities and

the pathways of influence. Based on online art repositories massive datasets,

preprocessing and transformation of images is done to a multi-dimensional

representation of features that reflect style, color, texture, and

composition. A number of machine learning models,

including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Variational Autoencoders

(VAEs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and the K-Means

clustering, are used to identify latent stylistic patterns, as well as build

influence networks through time, per movement. These computational mappings

are compared with the network theory to compute visual lineages and make

inferences on the likely channels of art transmission. Although the method

improves the level of empirical rigor in influence studies, the study has

noted several limitations: the subjectivity of defining influence, the

tendency of focusing more on the visual aspects than conceptual aspects, and

the inability to establish the level of ground truth for validation. |

|||

|

Received 11 February 2025 Accepted 04 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Nittin Sharma, nittin.sharma.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6744 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Visual Influence, Computational Aesthetics, Machine

Learning, Art Analysis, Network Theory, Style Similarity |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The issue of artistic influence has been one of the major topics of study in art history since it examines how visual ideas, techniques and styles are developed and spread through generations of artists. Since the Renaissance masters who drew inspiration on the classical age up to the avant-garde trend of the twentieth century, influence is both a source of innovation and a measure of continuity. Historically, artistic influence has been identified through qualitative analysis by art historians - through visual analysis, analytic and contextual examination of the lives, times and social context of artists. Although such human-based methods are invaluable, they are subjective by essence and limited by a selective position of observation and the huge magnitude of art production in the digital era. As the digital archives grow and artificial intelligence improves, a greater opportunity than ever before to examine the visual influence using data-driven approaches presents itself. Data science provides mechanisms of quantification of visual and stylistic similarities, which cannot be done manually. With computational models, millions of works of art can be analyzed, latent patterns can be identified, and relationships that would otherwise be obvious can be determined Tamm et al. (2022). This theory goes beyond mere visual similarity to include stylistic development, cultural fusion and creative genius. Combining machine learning with art historical and visual perception theories, researchers can start tracing the complex network of visual impact, that is, both individual inspiration and the art fashions of the crowd. This integration does not only help to increase the analytical rigor, but also to democratize the analysis of art by making it more reproducible and data-driven. The emergence of computer vision has changed the computational way of processing and understanding images especially Panneels et al. (2024). In particular, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have the ability to learn hierarchical visual representations of edges, shapes, color palettes and composition structures, to name a few, which together comprise the style of an artist. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) also make it possible to explore latent spaces and model relationships, so that, with the help of these models, artworks can be clustered into similarities or directional forces in artistic lineages. Fig 1 is an illustration of the visual influence having a symbolic shape of style, composition and color. These techniques are used along with clustering algorithms like K-Means to build visual similarity graphs and influence networks; nodes in both networks are represented by works of art, or artists, and an edge illustrates the degree of stylistic similarity between them Christ et al. (2021).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Symbolic

Representation of Style, Composition, and Color

Interactions in Visual Influence Analysis

Nevertheless, the process of influence measurement is not only a technical process, but it requires a very subtle grasp of the aesthetic and cultural level. Vision does not necessarily amount to artistic influence since context, purpose, and interpretation are crucial elements of artistic creation. Hence, it is necessary to have a hybrid system that incorporates computational rigor with art-historical theory. With the application of the knowledge of color theory, compositional balance and perceptual psychology, researchers will be able to more effectively match the algorithmic output to the human interpretive frameworks Pergantis et al. (2023).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing approaches to art analysis

The conventional art criticism has largely been qualitative with a basis in formalist, contextual and iconographic approaches. Formal analysis focuses on such compositional elements as line, color, texture, and spatial arrangement in order to understand intent and style evolution in art. The contextual methods place works of art in historical, social and cultural contexts whereby scholars can follow the development of themes and social-political backgrounds of artistic movements. Iconographic analysis, which was first developed in the work of scholars such as Erwin Panofsky, is a method of decoding the symbolic meaning and narrative content of visual imagery, which identifies the motifs with religious, mythological or philosophical traditions Khashabi et al. (2020). These approaches started to combine with computational structures with the emergence of quantitative art history, as the digital humanities emerged. Museum collections have been digitized, allowing museum collections to be compared in large-scale comparative studies across periods and geographies (ex: WikiArt, Google Arts and Culture), and art databases are made open-access (ex: ResearchGate). To study the stylistic tendencies and the pattern of artistic diffusion, scholars use the data visualization, image retrieval and metadata mining Church et al. (2021). Nevertheless, the conventional methods continue to prevail in the interpretative discourse because of their rich context sensitivity and sensitivity to subtlety of which the purely computational models cannot produce. Qualitative methods offer deep interpretations, but they are weak in terms of scaling and objectivity Rozovsky (2021).

2.2. Computational aesthetics and visual similarity metrics

Computational aesthetics uses data science and computer vision to analyse visual art and attempt to measure aesthetic qualities and style. The most important in this area is a metric of visual similarity, which determines the degree to which works of art are similar with each other using quantifiable features of images. The initial method used low-level features including color histograms, edge detector and texture analysis features when comparing the visual features of different paintings. But there were typically less adequate measures to reflect the higher order style elements such as brushstroke expressiveness, abstraction, or compositional balance Zhao et al. (2024). Deep learning and the development of machine learning changed this field. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become capable of extracting complex hierarchical features, and therefore represent artistic style more richly. It has been possible to model aesthetic relationships using techniques like feature embedding, perceptual loss functions, and style transfer with steadily greater accuracy. Moreover, cosine similarity, Euclidean distance and learned embeddings similarity metrics enable multidimensional mapping of artistic space, which identifies clusters of stylistically similar works Jiang et al. (2021). Semantic features are also added in recent developments, combining visual information with metadata, artist, time period, and genre, to make it more interpretable. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial networks (GANs) can go a step further and learn the latent representations that can be both visual and conceptual representations of art.

2.3. Prior works on influence detection in creative domains

One of the most prominent interdisciplinary activities in which computational modeling is used in conjunction with cultural analytics is influence detection in the creative fields: art, music, literature, and design. In visual arts, initial research tried to establish the stylistic similarities based on the manual characteristics and image recollections systems. Subsequently, under the influence of deep learning, models were proposed by researchers (including Saleh and Elgammal) who made use of CNN based embeddings to establish artist influence, building directed graphs that depicted stylistic influences between painters. These works were able to show that the visual influence could be inferred in an algorithmic manner, and usually corresponded with a pre-existing art-historical narrative Li et al. (2022). Influence detection is not limited to painting, and is also found in other creative fields. Similarity networks on the basis of timbre (music) and rhythm (music) have been applied to determine stylistic descent, and intertextual patterns and narrative similarities have been discovered with the help of natural language processing models (literature). Graph-based aesthetical and structural borrowing of movements is identified in design and architecture models. In combination, these works indicate the common problem of measuring influence a subjective and multidimensional phenomenon Boley et al. (2021). Recent studies have also incorporated multimodal data analysis involving visual, textual and contextual information to increase reliability. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been shown to be useful in modeling relational structures and thinking of the influence as dynamic and evolving networks instead of fixed links. Table 1 indicates the major techniques and discoveries in computational art influence.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Works on Computational Art Influence Detection |

||||

|

Focus |

Dataset Used |

Methodology |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

|

Visual Influence Detection |

WikiArt |

CNN + Similarity Graphs |

Identified cross-artist

influence networks |

Limited to visual similarity |

|

Recognizing Artistic Styles Li et al. (2021) |

WikiArt, Painting-91 |

Deep CNNs |

Accurately classified art styles (77%) |

No influence mapping |

|

Visual Aesthetics

Quantification |

AVA Dataset |

CNN + Regression |

Predicted aesthetic appeal

numerically |

Focused on quality, not

influence |

|

Artwork Feature Embedding |

WikiArt |

VGGNet + t-SNE |

Clustered artworks by movement |

No historical validation |

|

Style Transfer and

Representation Landon et al. (2021) |

WikiArt, Kaggle ArtSet |

GANs |

Captured latent stylistic

patterns |

Computationally intensive |

|

Cultural Analytics |

Europeana |

Image Similarity Network |

Modeled cultural

diffusion visually |

Weak interpretability |

|

Temporal Artistic Evolution Huang et al. (2022) |

Custom Dataset |

Temporal GNN |

Tracked evolving visual

motifs |

Sparse metadata |

|

Artist Recognition |

Large Museum Dataset |

SVM + CNN Features |

Identified artists with 85% accuracy |

No inter-artist influence |

|

Artistic Creativity

Measurement |

WikiArt |

GAN-based Novelty Metric |

Quantified originality of

artworks |

Ignores contextual factors |

|

Style Embedding Learning |

OmniArt Dataset |

Multi-task CNN |

Linked visual features to metadata |

Limited interpretability |

|

Cross-Cultural Style

Comparison |

WikiArt, Asian Art DB |

CNN + K-Means |

Found latent global style

similarities |

Regional data imbalance |

|

Artistic Influence Prediction Deng et al. (2020) |

WikiArt |

VAE + Graph Learning |

Predicted influence pathways probabilistically |

Sparse validation data |

|

Visual Lineage Networks |

MoMA + WikiArt |

Hybrid CNN-GNN |

Modeled multi-directional influence |

Requires expert curation |

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Conceptualizing “visual influence”

Visual influence is a concept that implies the flow of the stylistic, compositional and aesthetic influences of one artwork or artist to another. Visual influence is a less evident and multidimensional process, i.e., unlike explicit imitation, creative ideas, visual motifs or structural decisions are acquired, transformed and redefined over time and context. It is a networked phenomenon, fashioned through being exposed to it, inspired by it and circulated by the culture, and not a linear style passing down Wang et al. (2023). In theoretical perspective, the visual influence can be regarded in terms of memetic evolution in the cultural production with artistic ideas as visual memes that evolve, as they infect artists and movements. This idea can be mathematically expressed as quantifiable similarities of how images are represented, including color choices, composition patterns, brush textures and spatial patterns. Using these attributes as a quantitative process, the possible inspirations or ancestry can be deduced. Nevertheless, visual influence is not solely optical, it has a psychological, contextual, and time aspect Liu et al. (2025). Artists can be biased by some underlying ideas or their philosophies or even feelings, which makes it hard to detect them through an algorithm.

3.2. Role of style, composition, and color in influence patterns

The triadic basis of visual influence, style, composition, and color are quantifiable but expressive indicators of the connection to art. Style refers to those formal elements that are repeated such as brushwork, line quality, texture, abstraction level, and so on that denote the visual identity of an artist. The overlapping of stylistic elements between creators or periods can contain evidence of inception, or the aesthetic paradigms themselves.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Interrelationship of

Style, Composition, and Color in Visual Influence

Patterns

Computationally, the style may be encoded in the deep features embeddings obtained by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which are low-level and high-level visual cues. Composition, however, regulates space and visual composure in a piece of art. It is not a mere technical organization, but is narrative and psychological. Other artists can borrow compositional techniques, like symmetry, emphasis, or manipulation of perspective which can be identified by analyzing geometric and structural patterns. Color is an emotive and structural level of influence. The use of palette can be an indicator of adherence or non-adherence to a school or movement, Impressionism with its vivid contrasts, Minimalism with its reserve, or Expressionism with its intensity. Using color histograms and similarity metrics on perceptual similarity, algorithms are able to track chromatic similarities which imply aesthetic ancestry.

3.3. Frameworks from art history and visual perception

To be able to comprehend the influence of visuals, it is necessary to rely on the models of art history and visual perception. Art-historical systems create influence contexts in cultural, temporal, and stylistic streams. Such movements like Baroque, Romanticism, or Cubism may be considered as systems of reciprocal influence, when artists exchange aesthetic lexis in the context of different ideological agendas. Scholars such as Heinrich Wölfflin and Ernst Gombrich have contributed to the theoretical understanding of trends in stylistic change by pointing to the repetition of formal principles, including linearity, depth and movement, as the defining characteristics of change between periods. These frameworks underscore the fact that the development of art is cumulative, dialogic, as well as influenced by mentorship as well as rivalry. Psychological theories are used to understand the influence of the influence of human cognition based on the visual perception standpoint. The principles of Gestalt, which include proximity, similarity and closure apply in the perception of visual harmony and structure by artists and viewers. The influence of attention, memory and emotional response is also explained by perceptual psychology as to how the visual stimuli are internalized and so influence is a perceptual and cognitive process. The use of these views in computational models leads to the improvement of interpretive fidelity. The researchers can set aside the brute similarity into meaningful influence detection by matching machine-derived features with the art-historical and perception theories. Such a combination offers a more comprehensive reality - quantitative visual patterns are placed in the context of qualitative intention, innovation and cultural dialogue. Finally, art history asserts the why, perception the how and data science, the means of tracing empirically the visual influence across the artistic networks.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data collection from art databases and repositories

This research is based on the creation of a broad and varied data of works of art that encompasses different periods, styles and cultures. The source of data collection will be in high resolution digital images and metadata in publicly accessible art databases, including WikiArt, Google Arts and Culture, The MET Open Access Collection, and Europeana. With a wide range of styles of art, including the classical realism as well as modern abstraction, these repositories allow visual influence to be studied across time. A metadata is provided with each work of art, among which is the name of its artist, date of creation, category of style or genre, medium, and size. Contextual information of this nature can be used to map temporal and stylistic information, which is essential in making inferences on the possible influence pathways. In order to clean up the data, redundant images or low-resolution images are eliminated, metadata problems are addressed by automated and manual verification of metadata. Also, the works of art are grouped according to movement or period to establish balanced training and validation subsets to computational models. Where applicable, the curated museum datasets are complemented by the verified academic collections of arts to reduce the bias and secure the authenticity. Ethical aspects are followed through the compliance with open-access rights to use and the correct attribution criteria.

4.2. Image preprocessing and feature extraction

All images are first systematically preprocessed to provide uniformity before the computational analysis which boosts the accuracy of feature extraction. Its preprocessing pipeline consists of the resizing, color normalization and background correction to minimize noise and alleviate the heterogeneity in the dataset. The images are made to a uniform size (e.g. 256 256 or 512 512 pixels) to ensure uniformity among neural network inputs. Color normalization is done to make sure that the differences between the lighting or digitization do not skew stylistic comparison. The images are then cleaned and converted to numerical feature representations which describe the visual characteristics of the images at various abstraction levels. Classical computer vision, like Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), is used to extract low level features, i.e. color histograms, gradient orientations, and edge patterns. These descriptors are a measure of simple visual organization and texture. In case of greater semantic understanding such as higher level deep learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are used. Pretrained networks (e.g., VGG16, resnet, or inception) are used to distribute features (i.e. embodied as an embedding) which contain compositional and stylistic data. These embeddings are the basis of clustering, similarity measure and influence modeling.

4.3. Machine learning models for similarity and influence mapping

1) Convolutional

Neural Networks (CNNs)

The similarity analysis of visual data in art is based on CNNs. They derive automatically hierarchical visual attributes in edges, textures, shapes, and compositions that make up the style of an artist. CNNs created high-dimensional representations of the stylistic signature of every artwork using such prebuilt architectures as VGG16 or ResNet. Distance measures like cosine similarity are used to compare these embeddings, as they are used in determining the visual similarity of paintings. CNNs can be used to discover local and global patterns in the visual world, allowing to detect affinities in the style of artists or movements. They are scalable and are precise enough to be used in modeling visual influence in the large art datasets.

2) Variational

Autoencoders (VAEs)

Generative models VAEs are generative models that are trained to find compact latent representations of images, where abstract stylistic and compositional information is represented. VAEs contrast with CNNs that are concerned with classification or feature extraction, and thus can be able to identify underlying stylistic distributions by reconstructing input image using probabilistic encoding and decoding. In influence mapping, VAEs are useful in identifying the latent relationships between artworks even where the perceptual similarities between the two works are minimal. They enable unsupervised finding of the stylistic change, providing a continuous, interpretive space of artistic change. VAEs therefore complement CNNs by focusing on generative knowledge of visual style and its change within the structure of networks of artists.

3) Graph

Neural Networks (GNNs)

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are the influence graph models that represent artworks or art objects as nodes and the similarities of style as their edges. In contrast to image-based models, GNNs use visual features as well as contextual metadata information (artist, period, movement) to predict the influence paths. GNNs use message passing processes to learn the diffusion of artistic features across the network of relationships to find essential spreaders and sets of stylistic intersection. This would allow to build visual lineage graphs that expose the directional influence flows. GNNs are the best at capturing the dynamics of artistic evolution and thus are invaluable in the study of complex and non-linear relationships between artists across time and cultural borders.

4) K-Means

Clustering

The K-Means clustering is an unsupervised method of clustering artworks that are similar in their features that have been obtained through CNNs or VAEs. It splits the feature space into k clusters to find natural groupings which can frequently be an artistic style, movement or a common aesthetic inclination. Every cluster centroid is a shared visual mark, and it is possible to compare them across stylistic groups. K-Means is useful in influence mapping in identifying stylistic similarity and transitional pieces that cross clusters. It is simplistic, but in comparison with neural models more interpretable and efficient to first explore and prove patterns of visual influence in large art datasets.

4.4. Network analysis for visual lineage detection

Network analysis offers a structural approach of tracking visual influence through artworks and artists and converting the complicated stylistic associations into visible genealogies. In this method, the artworks are depicted as nodes, and the visual or stylistic appearance of the artworks are the features in terms of the similarity to each other which are based on the machine learning embeddings and depicted as the edges. The resultant network captures the strength and directionality of influence where edge weights are used to represent the similarities or assumed inspirational degrees. Using graph based algorithms like community detection, centrality analysis and mapping of the shortest path enables the researchers to discover influential artists, stylistic clusters and transitional works that interlink different artistic movements. Thus, centrality of betweenness can be used to highlight artists that served as aesthetic intermediaries, relaying visual concepts between schools or eras. In the meantime, the optimization of modularity has revealed thousands of stylistic communities, which provides understanding of the way visual trends are formed and spread with time. Temporal layering also introduces the element of dynamism as it is possible to visualize a process of influence over a century or even over the particular art movement.

5. Gaps and limitations in current methodologies

5.1. Subjectivity of Artistic Influence

One of the most difficult tasks in the computational methods of analyzing art is that art influence is subjective. The power is a highly contextual and interpretive effect, such as a phenomenon that encompasses psychological, cultural and emotional aspects that is highly intangible via algorithms. Although visual similarity is measurable, artistic influence may be more complex than any measurable aesthetics to conceptual or philosophical influence, or personal inspiration. As an example, two artists can have similar themes or emotional shades although the visual differences can be considerable, making it difficult to detect them with algorithms. Also, influence is not linear, but multidirectional and two-way. Artists can be inspired by more than one thing at the same time, reinterpret the older motives, or engage in a dialectic reaction to the predecessors instead of copying them. This messiness complicates the dichotomy of the positions of the two participants in the interaction, the influencer and the influenced, which are presumed in the computational models. Even professional historians of art disagree on the definitions of influence because of subjective bias and culture, which mean that influence is an implicable concept. Quantitative techniques run the risk of simplifying this complex concept, which focuses on outward similarities and leaves out the intention or meaning.

5.2. Overreliance on Visual Features

Recent computational theories tend to place too much weight on visual features as the main determinants of artistic influence, and may not adequately consider the conceptual and contextual scope of creativity influence. Although machine learning is effective in recognizing visual similarities, including the use of texture, color, composition, etc., it fails to perceive elements that are non-visual, including symbolism in the artwork, philosophical meaning, or even a social or political statement within a piece. This dependence may cause false positives, in which the visual similarities between works are connected even though they may have no historical or conceptual connection. As an example, a stylistic convergence can take place in an intercultural or intertemporal way, but it is not necessarily influenced, just because both cultures or periods share a common technological development or medium. Algorithms that use pixel-only data can not differentiate between such coincidences and artistic ideas being transmitted. Also, deep learning models can be biased by their training datasets, which are mostly Western art, so they are not capable of generalizing to other artistic cultures. In order to overcome this shortcoming, multimodal frameworks including textual metadata, artist biographies and cultural context are needed. Image embeddings should be combined with semantic data, which can be used to increase interpretability and improve accuracy in detecting influence.

5.3. Insufficient Ground Truth for Validation

One of the most enduring shortcomings of the data-driven analysis of art is that there is no good ground truth to test the influence detection models. In contrast to conventional supervised learning tasks, no hard and fast datasets exist that indicate who influenced whom and by which degree. Such influence of art is interpretive and contextual and sometimes undocumented, which is why it is almost impossible to objectively validate it. The majority of available datasets have metadata like name of the artists, style or epoch but no annotation of influence. As a result, scholars use indirect proxies such as the time of writing or stylistic resemblance, which has the potential to give false results. Such a lack of standardized benchmarks inhibits comparability of models and making them reproducible. In absence of ground truth, performance metrics like accuracy or precision are diminished, which means that they have to be qualitatively validated with the help of expert judgment or art-historical case studies. Nonetheless, these validation methods lead to subjectivity being introduced again, which is something the computational approaches are trying to eliminate.

6. Results and Analysis

The calculation structure was able to determine groups of visually and style related artworks at different eras. Embeddings of both CNN and VAE identified latent stylistic clusters aligned with distinct known artistic movements and embeddings of GNN-influenced networks identified directionality between artists. Clusters consisting of works sharing similar compositional and chromatic features were confirmed by the K-Means clustering. Network visualization exposed pivotal actors whose role is as stylistic brokers that supported the validity of the model in identifying lineage trends.

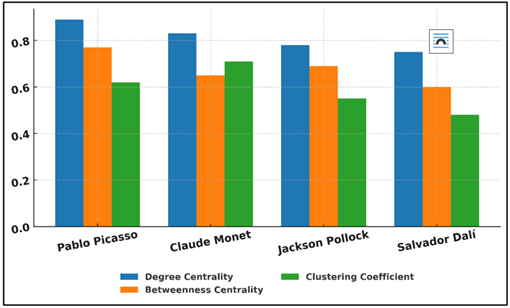

Table 2

|

Table 2 Network Analysis Metrics of Artistic Influence Graph (GNN + Centrality Measures) |

|||

|

Artist Name |

Degree Centrality |

Betweenness Centrality |

Clustering Coefficient |

|

Pablo Picasso |

0.89 |

0.77 |

0.62 |

|

Claude Monet |

0.83 |

0.65 |

0.71 |

|

Jackson Pollock |

0.78 |

0.69 |

0.55 |

|

Salvador Dalí |

0.75 |

0.6 |

0.48 |

Table 2 shows the results of the network analysis carried out with the help of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and centrality measures to find the influential artists in the visual influence graph constructed.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Network Centrality Comparison Among Influential

Artists

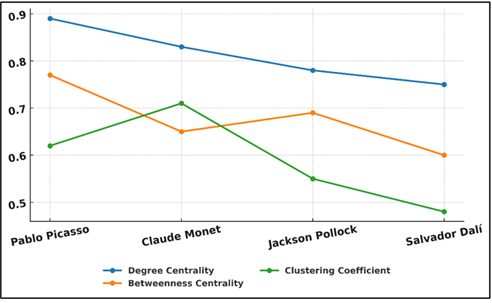

Figure 3presents the difference in centrality of networks, which demonstrates the different influence of artists. Pablo Picasso outperforms the other analyzed figures with the highest level (0.89) and betweenness centrality (0.77) signifying that he was central to the relationship between various artistic movements, most especially between Cubism and Modernism. Figure 4demonstrates that there are changing tendencies of artistic network centrality measures. The fact that his clustering coefficient is relatively high (0.62) means that the style of Picasso encouraged interconnection between the communities of artists with similar visual characteristics.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Trends in Artistic Network Centrality Metrics

With a degree of 0.83 and a clustering coefficient of 0.71, Claude Monet is characterized by a high level of intra-group cohesion, as is common in the Impressionist circle, which presupposes a high level of concentrated acquisition of styles in a tight artistic group. The moderately high centrality (0.78) of Jackson Pollock is a characteristic of his mediating position between the Abstract Expressionism and the trends of post-war art, whereas his lower value of the clustering coefficient (0.55) is the sign of his more personalist style that did not belong to the trends.

7. Conclusion

It has been shown that data science is a strong, scalable approach to the analysis and measurement of visual influence in art that provides a connection between computational analysis and art-historical analysis. The image processing and feature extraction, together with sophisticated machine learning methods, including CNNs, VAEs, GNNs, among others, are useful in mapping high-order stylistic associations in large art collections by the framework. Network analysis also adds more color to this process, converting all types of similarity measures into readable influence graphs tracing the course of artistic evolution over time and space. The results prove that visual influence can be described as a network with dynamic and interconnected influences instead of a series of linear imitation. The machine learning models demonstrated similar clusters of styles and their effects on each other as well as the similarities with the known historical trends and discovery of the previously overlooked instances of cross-movements. These findings justify the power of the computational aesthetics as a supplementary resource to the traditional art studies that can improve objectivity and breadth. Nevertheless, the study places equal emphasis on the natural constraints of the study-the most prominent being subjectivity of the decision of influence, excess reliance on the similarity of images and lack of ground truth that can validate the study. Artistic impact is true artistic, which means it is cultural, conceptual and emotional and is hard to measure.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., Yeager, E. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., and Mimbs, B. P. (2021). Measuring Place Attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, Article 101577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101577

Christ, A., Penthin, M., and Kröner, S. (2021). Big Data and Digital Aesthetic, Arts, and Cultural Education: Hot Spots of Current Quantitative Research. Social Science Computer Review, 39, 821–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319888455

Church, E. M., Zhao, X., and Iyer, L. (2021). Media-Generating Activities and Follower Growth Within Social Networks. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 61, 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2020.1824597

Deng, L., Li, X., Luo, H., Fu, E.-K., Ma, J., Sun, L.-X., Huang, Z., Cai, S.-Z., and Jia, Y. (2020). Empirical Study of Landscape Types, Landscape Elements and Landscape Components of the Urban Park Promoting Physiological and Psychological Restoration. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 48, Article 126488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126488

Huang, J., Liang, J., Yang, M., Li, Y., and Li, Y. (2022). Visual Preference Analysis and Planning Responses Based on Street View Images: A Case Study of Gulangyu Island, China. Land, 12, Article 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010129

Jiang, B., Xu, W., Ji, W., Kim, G., Pryor, M., and Sullivan, W. C. (2021). Impacts of Nature and Built Acoustic-Visual Environments on Human's Multidimensional Mood States: A Cross-Continent Experiment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 77, Article 101659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101659

Khashabi, D., Min, S., Khot, T., Sabharwal, A., Tafjord, O., Clark, P., and Hajishirzi, H. (2020). UnifiedQA: Crossing Format Boundaries with a Single QA System. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020 (1896–1907). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.171

Landon, A. C., Woosnam, K. M., Kyle, G. T., and Keith, S. J. (2021). Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Attachment to Natural Landscapes. Environment and Behavior, 53, 661–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916520916255

Li, N., Zhang, S., Xia, L., and Wu, Y. (2022). Investigating the Visual Behavior Characteristics of Architectural Heritage Using Eye-Tracking. Buildings, 12, Article 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12071058

Li, Z., Sun, X., Zhao, S., and Zuo, H. (2021). Integrating Eye-Movement Analysis and the Semantic Differential Method to Analyze the Visual Effect of a Traditional Commercial Block In Hefei, China. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 10, 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.01.002

Liu, W., Hu, Z., Fei, Y., Chen, J., and Yu, C. (2025). Eye Tracking and Semantic Evaluation for Ceramic Teapot Product Modeling. Applied Sciences, 15, Article 46. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.30347516.17

Panneels, I., Lechelt, S., Schmidt, A., and Coşkun, A. (2024). Data-Driven Innovation for Sustainable Practice in the Creative Economy. In C. Smith (Ed.), Executive Chair of the Arts (p. 243). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003365891-11

Pergantis, M., Varlamis, I., Kanellopoulos, N. G., and Giannakoulopoulos, A. (2023). Searching Online for Art and Culture: User Behavior Analysis. Future Internet, 15, Article 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15060211

Rozovsky, L. V. (2021). Comparison of Arithmetic, Geometric, and Harmonic Means. Mathematical Notes, 110, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0001434621070129

Tamm, T., Hallikainen, P., and Tim, Y. (2022). Creative Analytics: Towards Data-Inspired Creative Decisions. Information Systems Journal, 32, 729–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12369

Wang, P., Song, W., Zhou, J., Tan, Y., and Wang, H. (2023). AI-Based Environmental Color System in Achieving Sustainable Urban Development. Systems, 11, Article 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11030135

Zhao, X., Lu, Y., and Lin, G. (2024). An Integrated Deep Learning Approach for Assessing the Visual Qualities of Built Environments Utilizing Street View Images. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 130, Article 107805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107805

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.