ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Management of Intellectual Property in AI-Generated Artworks

Dr. Tripti Sharma 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. J Jabez 2

,

Dr. J Jabez 2![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Varsha Agarwal 3

,

Dr. Varsha Agarwal 3![]()

![]() ,

Ankit Sachdeva 4

,

Ankit Sachdeva 4![]()

![]() , Velvizhi K 5

, Velvizhi K 5![]()

![]() , Ashmeet Kaur 6

, Ashmeet Kaur 6![]()

![]()

1 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering (Cyber Security), Noida

Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Professor,

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sathyabama Institute of Science

and Technology, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

3 Associate Professor, ISME - School of Management and Entrepreneurship,

ATLAS SkillTech University, Mumbai, Maharashtra,

India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab, India

5 Assistant

Professor, Department of Management, Aarupadai Veedu

Institute of Technology, Vinayaka Mission’s Research Foundation (DU), Tamil Nadu,

India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The recent

rapid evolution of AI-generated artworks has provoked the essence of

creativity and raised challenging questions concerning the manner

in which intellectual property (IP) is understood, obtained, and

implemented under the circumstances of the human-machines cooperation. The

paper shall discuss the evolving character of authorship, ownership, and

creative input concerning the generative AI systems

and how the traditional mechanisms of copyright occasionally fail to work in

favor as far as the algorithmically generated material is concerned. The

questions of ambiguity in relation to human intervention in prompt-based

generation, the obscurity of the position of training data on the generation

products, and the impossibility to make a distinction between the concepts of

inspiration, derivation, and infringement on machine-generated forms are the

key ones. These concerns are compounded by ethical concerns particularly

where there is no consent in the dataset on the use of copyrighted content or

culturally sensitive content. In the paper, the new risk-reduction

strategies, including the transparency of datasets, provenance records,

watermarking systems, and hybrid licensing systems that apportion

rights by the layers of contributor of builders, users, and platforms, are

addressed. The paper will outline the legal, ethical, and technical

considerations of the issue by saying that sustainable AI art IP management

should be based on the multi-disciplinary approach that would guarantee the innovation and equitability, as well as maintain

cultural respect and safeguard the inventors. The findings indicate that

there is a need to have single global standards, consentual

data regulations and future-oriented legal definitions that are befitting to

capture the fact of the human-AI co-creation.

Together, these solutions would offer a path to an IP framework that would

assist in supporting the expanding creative frontier that is being

established by AI technologies. |

|||

|

Received 25 January 2025 Accepted 15 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Tripti Sharma, tripti.sharma@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6742 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated Art, Copyright Law, Authorship, Data

Ethics, Dataset Governance, Licensing Frameworks, Provenance Tracking,

Platform Policy |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Algorithms

that can be used to generate paintings, music, animations and even intricate

multimodal compositions now effectively stand next to human artists such as unwearying apprentices with flawless memory and

unpredictable sophistication Picht (2023). With the

artists, technologists and cultural institutions experimenting with these new

creative alliances, questions of intellectual property (IP) become a background

as shadows before a new light. Is it possible to say that creativity can be

linked to something which lacks consciousness? What are the duties after the

imagination of a machine is influenced by millions of human-made work? These are the questions that the current discussion of

the world revolves around, so IP management becomes one of the most pressing

issues in the age of creativity with the help of AI Garg (2023). The growth of

generative models has erased classic lines of authorship and originality.

Although previous digital solutions were used as brushes or lenses controlled

entirely by human will, the modern AI systems, particularly those based on deep

learning, can provide semi-autonomous creative capabilities. They recombine,

restructured and rethink the information based on the mass training corpora.

This renders the resultant production familiar and new as a mosaic made out of

pieces of forgotten galleries. This quality, however, makes it harder to

legalize creative contribution, in which the past has depended on human

intellect and self-expression William et al. (2023). The

protection of AI-generated content in many jurisdictions continues to be in a

legal grey area whereby the author is not a human being

and the enforceability of any copyright is undermined.

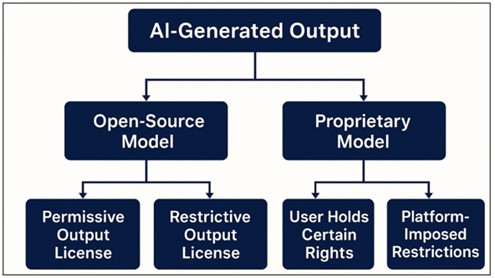

Figure 1

Figure 1 Human–AI IP Interaction Block Diagram Model

Combined

with legal doubts, there are ethical and practical issues that arise due to the

training of the AI systems. The datasets used to train models are frequently

scraped off the internet, which contains copyrighted artworks the creators of

which may never have given their permission to such use. It poses a conflict of

innovation and decency, with critics citing that AI systems are enjoying the

work of many artists and do not even give them credit Solbrekk (2021). In the

meantime, licenses of platform-specific terms of use, which lie between a free

open-source license and a prohibitive commercial contract, provide an

additional complexity to the matter and define the opportunities available to

users in utilizing and monetizing AI-generated content as illustrated in Figure 1. With the

growing utilization of generative AI in industries, IP management proves to be

very important in protecting creative ecosystems. Artists would like to be sure

that their work is not going to be watered down, copied, and used. Developers

need to find an answer to the question of liability. It is not easy for the

policymakers to develop innovative policies and at the same time be fair. These

conflicts of interest ensure that the issue of IP management in AI generated

art becomes a complex multi-disciplinary question that involves the

understanding of law, ethical considerations and technological knowledge Ghanghash (2022).

The

study examines the concept of the intellectual property being handled

responsibly in the time of machine-creativity. It aims to map the changing

landscape of human expression at the crossroads of algorithmic production, as

well as providing the roads to enable harmonized, prospective policy-making by analyzing the

controversies of legal frameworks, authorship, and ethics, and for new

technological solutions.

2. Conceptual and Legal Foundations

The

intellectual property of art created with AI technologies is based on a set of

fundamental ideas under which societies have conventionally organized the

definition of creativity, ownership and protection. With algorithmic creation

these pillars are calligraphy which is the same as old maps being drawn on the

new continents, the boundaries still display De Rassenfosse et al. (2023), yet the land

underneath those boundaries have changed. These are just some of the basic

principles that one has to know before investigating more intricate issues of

ownership and enforcement. The very core of the debate is the notion of

authorship, which traditionally needed human mind to create the creativity of a

piece. Most jurisdictions have made copyright doctrines based

on the fact that originality is the result of human intellectual

activity, a jolt of willfulness worked into the

ultimate product Aziz (2023). This is made

more difficult by the fact that AI systems tend to be the source of outputs

that are produced by statistical forecasting instead of by the conscious

artistic eye. Although users can create prompts or control the process of

iteration, the inner decisions made by the model are opaque, produced with the

help of layers of learned patterns Israhandi (2023). This

generates a conflict between the human hand pushing the system and the logic of

the machine doing the work, and the lawmakers have to discuss the extent to

which the human input suffices to offer protection to an artwork.

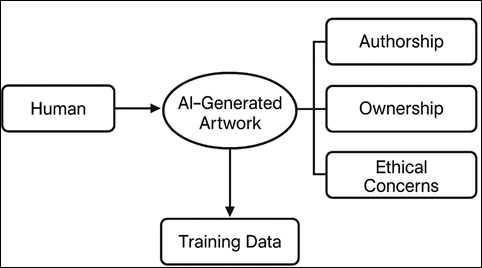

Figure 2

Figure 2

Human–AI Creative

Contribution Spectrum

Originality

is the second pillar which has conventionally been perceived as an

independently constructed work that exhibits low creative flair. Millions of

existing works are also fed into AI systems, and the model internalizes the

pattern as opposed to copying it Weisenberger and Edmunds (2023). However, this

distinction between inspiration and derivation is unclear when the machine is

an opaque process of learning. Courts have started to think that the

AI-generated outputs can possibly ever be meaningfully original when they are

produced in the shadow of so many hidden influences. With the changing nature

of the discussion, originality might require a redefined sense to consider the

computational creativity without the unwarranted extraction of the already

established artworks as illustrated in Figure 2.

Its

legal basis is the legal status of the AI-generated outputs. Non-human authors

are not considered as such and such works are

copyrightable in numerous countries at present. In certain jurisdictions, a

human in the loop may claim rights when his part has been creative enough,

whilst in others they may not allow claims at all when the machine has done the

expressive work Famiglietti and Ellerbach

(2023). This

disjointed international strategy makes the task of artists and businesses,

particularly the ones that operate internationally, uncertain. The legal

discussion becomes further when we look at the place of training data, which

exists in the nexus of copyright, fair use, and database rights. The question

of whether training on copyrighted content qualifies as infringement is

debatable and lawsuits as well as regulation proposals continue to seek to

define the boundaries. Others propose that training is non-expressive and

transformative and others perceive it as an unlicensed exploitation of cultural

labor.

3. Authorship, Ownership, and Creative Contribution

Whether

an AI-generated artwork can be regarded as the author of the given work is the

central matter of the intellectual property issue, creating one of the most

complicated knots in the field. Conventional authorship presupposes a human

mind, which defines the expressive decisions, a creative spark that leads the

work between the will and the end design Ning (2023). In the

AI-mediated creation, however, this spark is diffused over human instructions,

algorithmic processes and large-scale statistical inference. When a human being

enters some prompts, refines outputs, adjusts parameters, or culls variations,

his or her hand is like a constant hand on the rudder of a vessel being driven

by an unknown engine. The creative input exists, though it is not consistently

preeminent, and laws differ greatly in the extent to which human intervention

is needed before authorship is achievable. Certain jurisdictions would require

physical control of expressive elements based on data provided in Table 1, whereas, in

other jurisdictions, a conceptual direction or high-level decision making is

deemed adequate and the boundary between authorship and facilitation is

constantly shifting Bisoyi (2022).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Comparative Analysis of

Licensing Approaches |

||||

|

License Type |

Restrictiveness Level |

User Rights |

Limitations |

Typical Use Case |

|

MIT License |

Very Low |

Full reuse and modification |

No content protection |

Open-source research |

|

Apache 2.0 |

Low |

Broad use + patent grant |

Attribution required |

Academic/industrial models |

|

CC-BY |

Medium |

Reuse with attribution |

No control of derivatives |

Creative content sharing |

|

Proprietary A |

High |

Limited output rights |

Usage restrictions |

AI art platforms |

|

Proprietary B |

Very High |

Restricted commercial use |

Strict platform control |

Corporate AI systems |

The

situation of ownership is also problematic. Under the traditional copyright

models, ownership is a natural progression of authorship, whereas with AI

systems the rights chain extends further to include: the model developers, the

dataset curators, the platform providers and the final-users

who create the artwork. All these participants do not play the same role in the

end result. The architecture and training rules are designed by developers, the

training data are collected and organized by the curators, and the prompts

through which the generative engine operates are designed by the users. Who

owns the output is thus less of a question of determining who the one creator

is, and more one of comprehending the ways of joining different types of

creative work together. Other platform terms of service endeavor

to address this by assigning rights to the user on generation, whereas some

retain partial or complete rights to the outputs. This contractual layer

frequently takes the role of default authority on ownership, particularly in a

jurisdiction where AI-generated work is not considered a piece of copyrightable

content Vig (2022).

The

idea of creative contribution makes the situation even more complicated. In art

created by man, creativity is regarded not as in the final product itself but

in the decisions, revisions and interpretations that lead to the development of

the product. The value added by the user can be the richness and richness of

the prompt, or the curative loop that filters and narrows down the outputs.

Although the role of the AI is mechanical, it can include the creation of

expressive details, which the user was not necessarily imagining. This creates

some very critical questions: Is creativity calculated by intention, by process

or by aesthetic result? Is the autonomous generation behaviour of the model to

be regarded as part of creative equation, although it is not conscious? And in

case such a model accesses stylistic patterns of a vast array of human works in

training data, what about the invisible community of creators whose work passes

through the algorithm?

4. Training Data, Ethical Use, and Licensing Issues

The

basis of AI-made art has been constructed on the foundations of vast pools of

training data and this implicit substrate influences

the aesthetic behaviors of the generative models as

well as the ethical and legal controversies that have emerged around them.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Ethical Risk Matrix for AI

Training Data |

||||

|

Dataset Type |

Ethical Risk Level |

Legal Risk Level |

Primary Concern |

Example Cases |

|

Copyrighted Artwork |

High |

High |

Unauthorized scraping |

Illustrator lawsuits |

|

Cultural Heritage Data |

High |

Medium |

Misappropriation and

distortion |

Tribal motif misuse |

|

Sensitive Imagery |

Very High |

Very High |

Privacy & harm |

Faces, medical images |

|

Public Domain Data |

Low |

Low |

Minimal risk |

Historical archives |

|

Licensed Databases |

Low |

Medium |

Contractual compliance |

Commercial datasets |

Training

datasets can also be viewed as enormous libraries that are uncated

and in which images, paintings, cultural trends, and stylistic items can freely

linger. Although these datasets can be used to train AI systems to learn rich

visual structures, they are often built by mass scraping online material, most

of which is legally regulated, culturally sensitive, or created without its

presence in a machine-based learning pipeline as in data provided in Table 2. This brings a

major question, does a model have the right to learn morally or legally, of

works in which it has no right to do so? The positive viewpoint on training

tends to emphasize that it is a process of non-expressive, transformative

activity that resembles a student learning about art history, whereas many

critics view it as an industrial-level exploitation of creative work without

any attribution, consent or payment. Consequently, the dataset turns out as the

source of creativity as well as the contention of ethical controversy. Ethics

of training data go into the realms of culture as well. Indigenous motifs,

sacred symbols or traditional designs that are not owned by an individual can

be inadvertently captured by the AI systems and used across the board. When

such trends are revealed in the outputs of AI, they run a risk of becoming

unattached to the cultural identities that make them relevant and heritage

becomes a raw material to be remixed by algorithms.

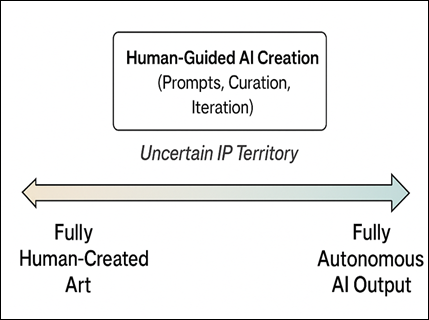

Figure 3

Figure 3

AI Training Data

Ethical Risk Map

Another

factor that adds to the complexity is the problem of licensing, which specifies

a manner of how users can interact legally with the AI-generated outputs.

Various models have different licensing regimes and the terms can determine

whether a work of art can be commercialized or repackaged as in Figure 3, revamped,

re-used or incorporated into other creative works. Open

source models often come with wide ranging freedoms,

but are sometimes accompanied by terms of use which limit their harmful

or deceptive use. Proprietary models on the other hand depend on platform

specifications that determine ownership, use limitations and content

limitations. Other sites allow creators to enjoy complete commercial rights to

work, whereas others demand joint ownership, or take downstream restrictions.

Since most jurisdictions do not secure AI-generated works under copyright, such

licenses can serve as an alternative legal framework, serving the role of

scaffolding that supports an incomplete legal framework until the final legal

framework can be developed.

5. IP Enforcement, Risk Management, and Emerging Solutions

Intellectual

property rights in the AI-generated artworks are one of the most complicated

frontiers in the modern creative governance. Classical enforcement is based on

the idea of detecting copying or unlicensed derivatives, but it is challenging

with the products of AI generation since they are not necessarily duplications

but can represent statistical copies. In a case where a model is creating a

piece of art that has a similarity to a safeguarded style or motif, the

similarity can be diffuse, by chance, or a result of training patterns and not

an intentional imitation. With this, enforcement will be like trying to chase a

shadow which does not exactly come into a standstill. The holders of rights

have challenges in proving substantial embodiment or showing that there is

guarded articulation in the output of the model. In the meantime, platforms

have a hard time formulating policies which would allow freedom of users and

stop the exploitation of current artists. In the absence of common standards,

enforcement turns piecemeal, moving away into courtroom combat, to

platform-specific rules which can be highly uneven in their degree of fairness

and transparency.

Figure 4

Figure 4

AI Art IP

Enforcement Lifecycle

Risk

management is becoming a major aspect as inventors

companies and organizations are trying to cross this grey terrain. Artists have

concerns about their work being consumed into datasets without their permission

such as in an unwanted distortionary stylistic parody. Those companies which

employ AI technology are concerned about how they may accidentally upload

unauthorized content which will be used to bring forward a claim of copyright

infringement, reputational harm or breach of contract. In order to reduce these

risks, new forms of best practice, focus on documentation and transparency.

Other organizations also have internal IP compliance policies, consider as high risk assets, or users verify the sources of sensitive

material. Such measures are like navigators who are distorting in uncertain

waters that provide a structure and predictability despite lawful shoreline

being far away as shown in Figure 4. There is also

the development of new technical and regulatory approaches for responsibility

and enforcement in the field. Generative models are being introduced with

watermarking technology that can be used to add identifiers to output through

invisible and cryptography marks. Registries based on blockchain also assist in

provenance as they give an immutable time and ownership record, which can be

especially handy in the context of claiming rights in a jurisdiction where

copyright laws are ambiguous. At the regulatory level, policymakers are

deliberating on frameworks concerning the transparency on training-data,

disclosure of output and liability on the part of the developers. Among the

proposals are compulsory labeling the datasets,

opt-out of artists, and standard notices about the extent of human

participation in a created work.

6. Interpretation and Analysis

The

results of the study demonstrate that there is a creative ecosystem in flux,

with the old intellectual property structures being overloaded with the burden

of new generative technologies. In every part, the results are drawn to the

same central conclusion: AI-generated art does not fit in any of the existing

legal or ethical categories since it disperses the creative workforce across

human beings, machines, data, and technologies. This distribution creates a

topography in which authorship is diffusive, ownership is negotiated and not presupposed and creativity itself extends beyond its human

resources. The discussion highlights that the capabilities that render AI art

so potent, namely, its ability to acquire patterns, recycle styles, and create

new expressions, are the same ones that lead to the development of the

fundamental conflicts regarding accountability, fairness, and protection.

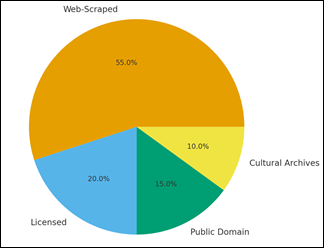

Figure 5

Figure 5 Proportions of Major Dataset Sources Used for

Training AI Art Generation Models

In

the Training Data Source Composition chart, it can be noted that web-scraped

content is the most significant contributor since it represents over fifty

percent of the data driving generative models as shown in Figure 5. Licensed and

open-source contents compose 35 percent of the total with culturally sensitive

archives occupying the least percentage. This imbalance raises important

ethical and legal issues because the usage of scraped content often does not

have explicit permission of original creators.

An

important consequence of this work is the fact that norms of authorship do not

readily project onto the creation mediated by machines any

more. The spectrum model that was created in the study demonstrates that

AI artworks exist on a continuum and they do not separate into a binary

opposition between "human-created" and "machine-generated."

The majority of creative outputs are in the gray

area, whereby the human will influence the generative process, but not entirely

control it. The implications of this shift to policymakers include the need to

re-evaluate the basis of copyright on human creativity or the need to recognize

the contribution of human hybridity in this case.

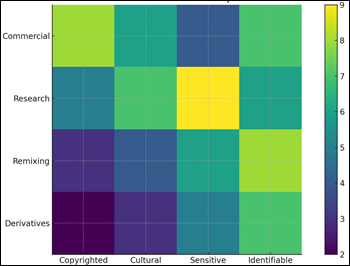

Figure 6

Figure 6 Heatmap Illustrating Ethical and Legal Risk Intensity Across

Dataset Types and Usage

Contexts.

The

Ethical Risk Heatmap offers a relative perspective of possible risks based on

the type of data set and its usage in the context of various applications. The

datasets with sensitive and identifiable-image pose

the highest risk scores, particularly when they are engaged in the research or

in the creation of derivatives. There are also increased dangers in commercial

and derivative uses in copyrighted and cultural content. This trend shows that

risk is not homogeneous, it is greater based on the nature of the data as well

as the purpose of its utilization. The outcome analysis further indicates that

the ethical and legal section of the AI creativity line is the training data as

shown in Figure 6. The study

indicates that models that have been trained using large datasets (unconsented)

create unanswered questions regarding impartiality, cultural sensitivity, and

economic equality. Artists whose artworks are used to train corpora in some way or another feel a sense of deprivation when AI systems

emulate stylistic elements that belong to their own or cultural identities.

This supports the necessity of greater mechanisms of transparency,

consent-based data curation and community sensitive data governance. New

technologies such as opt-out registries, dataset labeling

and culturally sensitive training practices provide promising avenues, although

they are not uniformly used as an industry practice.

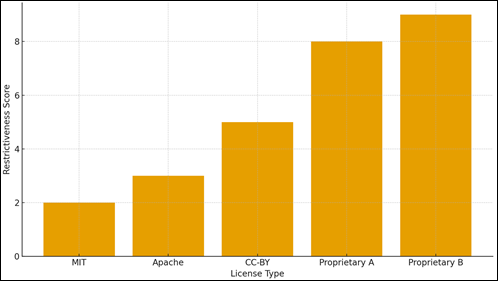

Figure 7

Figure 7 Comparative Restrictiveness Levels Among Open-Source and Proprietary AI

Model Licenses

The

index of the restrictiveness of the licensing has an evident gradient between

open-source licenses that have minimal restrictiveness and proprietary ones

that impose more severe restrictions on the use of output. Conversely,

proprietary structures are more restrictive, which is indicative of the

apprehensions of abuse, commercial ownership, and brand reputation. This

comparison demonstrates the significant difference in model accessibility and

user rights between the types of licensing, which will determine the

possibility to distribute AI-generated artworks and commercialize them as shown

in Figure 7. The analysis

of licensing and enforcement shows another complexity level: due to the lack of

the traditional copyright protection of the AI-generated results, the contracts

and platform licensing models have become informal IP regimes. This dominance on

a contractual basis provokes the issues of asymmetry of power where big

technological platforms possess rights, establish limits of use and determine

the terms which can dominate over the old rules of IP. The lifecycle as well as

the risk-management diagrams created in this study assist in demonstrating how

enforcement is being transferred out of the system of public law to the system

of a platform-controlled enforcement. Although these platform protocols give

short-term transparency, they could also have a negative effect on the

disintegration of global creative standards, as well as on the long-term

independence of users of their own works.

7. Conclusion and Future Directions

The

high pace of development of AI-generated works has put intellectual property

arguments in a different field of operation, exposing an apparent

incompatibility between the classic legal principles and the ambivalent

character of human-AI creativity. Generative models pose a threat to authorship

by doing what expressive tasks used to be carried out by humans. The ownership

is disputed between developers, dataset curators, platforms, and end-users who

all play a part in the creative chain. Ethical concerns are raised from the

murky practice of training data and raise concerns of consent, cultural

integrity, and the unacknowledged influence of human artists whose creations

are used to train algorithms. Simultaneously, it becomes difficult to enforce

as the courts are dealing with the issue of copying on the basis of algorithms

and not direct copying. These tensions are signs not of the failure of IP

governance, but transition. Such new solutions as watermarking, blockchain

provenance, dataset transparency, hybrid licensing schemes and platform-level

policies are promising. They still are in their developing stage, but they

present a framework on which the creativity of machines can be harmonized with

fair and responsible rights management. They also point out that in order to

deal with the IP in AI art, it is necessary to collaborate in law, technology

and culture and in creative practice.

In

the future, there are priorities that is necessary. It is necessary that the

policymakers define the legality of the outputs created with the use of AI and

redefine the concept of originality and authorship to match the modern ways of

creating. Transparent data governance which is agreeable to both the parties

should be the norm. The technical research should continue in the development

of provenance tracking tools that can be trusted. The players in the industry

may be required to adopt dynamic licensing frameworks that have a stronger

expression of joint creative contribution. The coordination will also be

required internationally to avoid a piecemeal regulation and protect uniformly

across the borders.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aziz, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Produced Original Work: A New Approach to Copyright Protection and Ownership. European Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning, 2(2), 9–16.

Bisoyi, A. (2022). Ownership, Liability, Patentability, and Creativity Issues in Artificial Intelligence. Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 31(4), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/19393555.2022.2060879

Famiglietti, P., and Ellerbach, C. L. (2023). Protecting Brands in the Age of AI. Lexology.

De Rassenfosse,

G., Jaffe, A. B., and Wasserman, M. F. (2023). AI-Generated Inventions:

Implications for the Patent System. Southern

California Law Review, 96, 101–126.

Garg, A. (2023). IPR Issues Concerning Artificial

Intelligence – Patent – India. IPR Issues Concerning Artificial

Intelligence – Patent – India.

Ghanghash, S. (2022). Intellectual

Property Rights in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: A study Reflecting Challenges in India

and International Perspective. International Journal of Multidisciplinary

Journal of Educational Research,

11(6), 72–80.

Israhandi, E. I. (2023). The Impact of Developments in Artificial

Intelligence on Copyright and Other Intellectual Property Laws.

Journal of Law and Sustainability Development,

11(11), e1965.

Ning, H. (2023). Is it Fair? Is it Competitive? Is it Human? Artificial Intelligence and the Extent to Which We can Patent AI-Assisted Inventions. Journal of Legislation, 49(2), 421–448.

Picht, P. G. (2023). AI and IP: Theory to Policy and Back Again – Policy and Research Recommendations at the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property. IIC – International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 52, 916–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-023-01344-5

Solbrekk, K. F. (2021). Three Routes to Protecting AI Systems and Their Algorithms Under IP Law: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice, 16(3), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpab033

Vig, S. (2022). Intellectual Property Rights and the Metaverse: An Indian Perspective. The Journal of World Intellectual Property, 25(3), 753–766.

Weisenberger, T., and Edmunds, N. (2023). Copyright and AI-Generated Content: Establishing Scope Requires More Than Registration. Lexology.

William, P., Agrawal, A., Rawat, N., Shrivastava, A., Srivastava, A. P., and Ashish. (2023). Enterprise Human Resource Management Model by Artificial Intelligence Digital Technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM). IEEE, 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCAKM58659.2023.10449624

William, P., Bani Ahmad, A. Y., Deepak, A., Gupta, R., Bajaj, K. K., and Deshmukh, R. (2023). Sustainable Implementation of Artificial Intelligence-Based Decision Support System for Irrigation Projects in the Development of Rural Settlements. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(3s), 48–56.

William, P., Panicker, A., Falah, A., Hussain, A., Shrivastava, A., and Khan, A. K. (2023). The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Contemporary Business Management. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Computation, Automation and Knowledge Management (ICCAKM), IEEE, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCAKM58659.2023.10449493

William, P., et al. (2023). Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Security as Advanced Technologies on Bitcoin Industries. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(3s), 131–140.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.