ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Digital Twin of Folk Art Museums for Education

Nidhi Ranjan 1![]() , Ashishika Singh 2

, Ashishika Singh 2![]()

![]() ,

Namrata Singh 3

,

Namrata Singh 3![]()

![]() ,

Vinod Chandrakant Todkari 4

,

Vinod Chandrakant Todkari 4![]() , Debasish Das 5

, Debasish Das 5![]()

![]() , Manvinder Brar 6

, Manvinder Brar 6![]()

![]()

1 Department of Engineering and Technology, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be University), Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

3 Assistant Professor,

Department of Master of Business Administration, Noida Institute of Engineering

and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vidya Pratishthans Kamalnayan Bajaj Institute of Engineering and Technology, Baramati, Pune, India

5 Department of

Computer Science and Engineering, Institute of Technical Education and

Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha,

India

6 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Embient

digital twin technology in the cultural heritage preservation system has

become a transformative method of learning and interaction in a folk museum

of art. This paper suggests the development and execution of a Digital Twin

Framework of Folk Art Museums that would contribute to increasing the

accessibility to education, understanding of culture, and experience. The

digital twin is capable of reflecting the physical conditions of things like

temperature, humidity, and light through 3D scanning, IoT-enabled sensors,

and an AI-driven knowledge graph, and to preserve and maintain an authentic

context. Also, machine learning algorithms learn user interactions to

customize education, and the virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR)

interface enables a person to explore folk art traditions and methods

immersively. Moreover, the interactive simulations can allow students to

study artistic procedures and cultural stories in the form of an interactive

process that links the classical craftsmanship to digital pedagogy. This is a

democratizing practice of folk art education, where remote learners and

researchers are able to interact with cultural heritage without being

constrained by geographical borders. The suggested system, therefore, becomes

a sustainable, intelligent, and educationally enriched digital ecosystem,

promoting cultural sustainability and creativity in learning in museums. The

paper is able to conclude that digital twins signify a paradigm shift in the

way folk art may be perceived, preserved and taught during the digital age. |

|||

|

Received 06 February 2025 Accepted 28 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Nidhi

Ranjan, nidhipranjan@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6723 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Digital Twin,

Folk Art Museum, Cultural Heritage Preservation, Scanning 3D, Internet of

Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented

Reality (AR), Predictive Maintenance |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Folk art museums are a living repository of

cultural identity, craftsmanship and local heritage and represent centuries of

artistic practice and local traditions. Nevertheless, those museums can be

characterized by such difficulties as preservation, access, and education

because of the delicate character of artifacts, territorial restrictions, and

the lack of visitor involvement. The incorporation of innovative technologies

into the process of cultural heritage documentation and experience in the

digital age has transformed the use and perception of cultural heritage, which

includes artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and

extended reality (XR). One of these advances, Digital Twin Technology, a

dynamic, online manifestation of material properties, is a radically new model

of rethinking the educational and operating environment of folk art museums Baek et al. (2024). Digital twin is

a data-driven, real-time virtual representation of the museum and collections,

and makes the two worlds interact with each other continuously. By implementing

sensors, 3D visualization and data analytics, all the artifacts, environmental

variables, and visitor interactions can be reflected, tracked, and examined to

improve preservation and learning experience.

When applied to folk art education, digital twins

create a drastic pedagogical change in education that focuses on passive

observation to the perspective of active, interactive learning. The physical

in-person experience of a museum offers few opportunities to get past the

sights and background of folk art, but a digital twin would enable a learner to

digitally interact with every object, explore its materials, methods, and

history, and even model the creative process that led to its creation. As an

example, using AR/VR interfaces, students are able to virtually enter a

recreated cultural environment (e.g. workshop in a village, rituals during a

festival, or market of crafts) to learn the sociocultural storyline behind the

folk art Adhau and Gadicha (2024). In addition,

personalized educational messages based on user preferences and learning

behaviour designed using AI-based recommendation systems in the digital twin

can be mathematically modelled by using optimization functions, e.g.

L is the loss function to optimize the content

accuracy and relevance. This is an adaptive mechanism that guarantees every

learner a unique experience that is in line with his or her cognitive profile

as well as academic goals. The digital twin can assist in predictive

preservation, providing a systematic monitoring of the environmental and

structural states of museum objects, which has a conservation perspective. Such

differential equations as

![]()

is capable of modeling the degradation of materials

with time, providing curators with the ability to prevent the degradation

impact by controlling the environment in real-time. Moreover, IoT sensors

placed in the museum infrastructure monitor the temperature, humidity, and

light intensity and send it to the digital twin to analyze and provide feedback

Mune et al. (2024). The combination

of machine learning models also supports anomaly detection and trend

forecasting, which guarantees maximum artifact preservation and performance. In

addition to technological innovation, the digital twin democratizes the process

of cultural learning because it cuts across geographical and economic lines.

Remote students are able to access museum’s collections via digital platforms

(cloud-based) hence conserve intangible heritage and enhance inclusivity Zhu et al. (2021). As a result, the

digital twin of folk art museums represents a

technology-meets-education-meets-culture ecosystem that will constitute a

sustainable, interactive, and intelligent system that will transform heritage

learning in the future generations.

2. Literature Survey

The compiled ten-point review generalizes the cross-cutting evidence related to the design, implementation, pedagogical embrace and operational implication of digital twin and related digital systems, in the case of folk art museums. The clusters are characterized by uniform empirical potential and realistic deployment options that exist in the form of concrete constraints. The technical principles are based on established technologies of geometric capture (3D scanning, photogrammetry) and increased use of inexpensive IoT sensors Nwoke et al. (2023). It has been repeatedly shown in the literature that high-resolution meshes and texture maps allow to perform detailed visual examination and facilitate immersive XR visualization; like in distributed sensor networks that allow to continuously monitor microclimates that have a material influence on folk-art conservation. But, again, there are methodological shortcomings: the photogrammetric precision of measurement is reduced on reflective or obscured surfaces, sensor data has a drift and needs to be calibrated, and there are irregular transmission issues. In addition, data-management burdens- storage, processing and archiving over a long period of time are often underestimated especially when projects are expanded beyond pilot sites. These limitations suggest that to have a strong digital twin pipelines, it is not only that you need to spend money on capturing data at the beginning but also that you need data engineering and maintenance investments on a long-term basis Chaudhari and Shrivastava (2024).

Affordances of education that are exposed in research are positive. AR/VR interventions are effective to enhance visitor engagement and assist in rebuilding contexts around intangible practices including folk weaving or ritual performance. Knowledge graphs and semantic layers make it easier to learn through a discovery oriented approach that connects artifacts to artisans, techniques, and local histories; relevance is extended by recommender systems to create more learning sequences to the profiles of the user Zheng and Tian. (2021). However, a gap in the evidence about the long-term learning outcomes exists: the majority of studies provide the results of a short-term nature (session time, immediate recall), whereas both long-term retention and transfer of cultural knowledge are not fully assessed. Moreover, personalization mechanisms create issues of the cold-start problem and the risk of algorithmic bias in the case of new users or under documented artifacts. To tackle these concerns, it would be necessary to conduct bigger studies involving stratified cohorts of users and recommenders with transparent designs with fairness and explainability criteria. A third axis that is critical is governance and sustainability. Ethical studies focus on the need of culturally sensitive consent, provenance, and community involvement particularly of living traditions and artifacts with sacred or proprietary significance Ji et al. (2021). Cost-benefit analysis suggests that net institutional benefits can be achieved over time through long-term use of systems integration and upfront digitization, which are costly in the short run. However, these economic implications are subject to estimated take-up, and financial viability as well as technical staffing; small museums can be prohibitively expensive to enter unless business models of collaboration or consortia are implemented or shared infrastructure. Legal complexity is also an issue with data governance: national and communal laws on cultural property, privacy, and data sovereignty are wildly different, making flexible policies and mechanisms of stakeholder engagement inevitable.

Theoretically, the literature supports the use of mixed-method types of prototypes that act as integrations of empirical sensor applications and controlled user testing and model-oriented predictions. Hybridization between physico-chemical models (e.g. material-specific decay equations) and empirical time-series learning methods is the advantage of predictive maintenance work Talasila et al. (2023). These hybrid models enhance interpretability and actionable practicability to conservators however need curated longitudinal datasets, which are imperative at the moment. Similarly, knowledge-graph technologies based semantic methods are promising to have interpretive depth, but the curation of ontologies is still labour-intensive and biased according to disciplinary viewpoints.

Table

1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Survey |

|||

|

Key findings |

Scope |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

Digital twins enable realistic,

time-synchronized replicas of museum spaces and artifacts, improving remote

access and conservation planning Zhu et al. (2021). |

Single-site museum pilot

(artifact-scale + environmental sensors). |

Real-time monitoring; enhanced remote

pedagogy; supports conservation decision-making. |

High initial cost; limited

generalizability from single-site pilots; integration complexity. |

|

High-fidelity 3D models capture

geometric and textural detail sufficient for close visual study and

simulation of restoration Nwoke

et al. (2023). |

Laboratory and field scans across

diverse artifact types. |

Accurate visual replication; supports

measurement and VR/AR applications. |

Large data volumes; occlusion and

reflective-surface problems; requires skilled operators. |

|

Continuous sensor streams permit early

detection of harmful microclimates and inform HVAC control strategies Chaudhari

and Shrivastava (2024). |

Multi-room deployments over extended

monitoring periods. |

Low-cost sensors enable granular

condition tracking; supports predictive alerts. |

Sensor drift and calibration issues;

network reliability; data security concerns. |

|

Immersive experiences increase

engagement, contextual understanding, and retention in controlled studies Zheng

and Tian. (2021). |

Short-term educational interventions

with students/visitors. |

High engagement; enables reconstruction

of intangible contexts; accessible remotely. |

Motion sickness risk; accessibility

barriers; limited long-term retention evidence. |

|

Personalization improves learner

relevance and on-platform engagement metrics; collaborative and content-based

methods effective Ji et

al. (2021) |

Prototype systems with small user

cohorts. |

Tailored learning paths; improved

content discovery; higher session times. |

Cold-start problem; potential bias in

recommendations; privacy concerns. |

|

Knowledge graphs improve navigation,

cross-referencing, and semantic search across collections Talasila

et al. (2023). |

Ontology construction for a museum or

collection subset. |

Rich semantic linking; supports

interpretive storytelling and query expansion. |

Ontology curation cost; heterogeneity

of source metadata; scalability challenges. |

|

Time-series and physical models

forecast risk windows for intervention, reducing unplanned deterioration Baek (2022). |

Model validation on historical

conservation and sensor datasets. |

Enables proactive conservation; reduces

cost of reactive repair. |

Model uncertainty for rare events; need

for long-term labeled data. |

|

User studies identify barriers:

navigation complexity, language, and device limitations; inclusive design

improves uptake Wadibhasme et

al. (2024). |

Mixed-method evaluations with diverse

demographic groups. |

Actionable design guidelines; improved

reach for underserved users. |

Small sample sizes; variability across

demographics; platform-specific constraints. |

|

Ethical frameworks stress consent,

cultural sensitivity, and provenance transparency for digitized cultural

materials Yusheng et al.

(2022). |

Policy analyses and stakeholder

interviews. |

Provides governance templates and

community-engagement practices. |

Tension between open access and

cultural restrictions; uneven legal frameworks. |

|

Cost–benefit assessments show long-term

educational and conservation gains may offset upfront costs for institutions

with sustained use Adhau and Gadicha (2024). |

Multi-factor economic modelling across

hypothetical adoption scenarios. |

Informs institutional decision-making;

highlights scaling thresholds. |

Results sensitive to assumed usage

rates; non-monetary cultural values hard to quantify. |

There are a

number of priorities in terms of research agenda. First, educational studies

are needed in longitudinal studies that will confirm the allegations regarding

the cultural transmission and retention of learning. Second, interoperable data

standards (of 3D models, environmental records and semantic metadata) would

increase the efficiency of work and allow cross-site comparative studies.

Third, to make digital twins mainstream, scalable governance mechanisms that

create a balance between open scholarly access and cultural sensitivity and

legal restriction are required. Lastly, economic models that would integrate

non-monetary cultural values like community well-being and continuity of

intangible heritage would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the impact

of a project. Overall, according to the literature, the problem of digital

twins in the folk art museums suggests a very promising intersection of

technological potential and educational possibility. The way to the mass and

sustainable application will be attentive to the quality of data, inclusive

design, ethical governance, and provable long-term educational results.

3. PROPOSED SYSTEM

3.1. Modeling and Environment Reconstruction

The step is aimed

at creating a spatial high-quality and visual-rich virtual copy of the folk art

museum in 3D. In point cloud data and photogrammetric input, polygonal meshes

of the artifacts, galleries, and other environmental features are created using

the tools of Blender and Unity3D. The equations of geometric transformation

control the reconstruction in which object coordinates are defined as:

![]()

Light intensity

models, including Lambertian reflectance theta are then used to do texture

mapping and surface rendering so that the visual fidelity is realistic.

Moreover, the semantic navigation and contextual storytelling is connected to

spatial metadata, which is associated with the digital ontology of the museum.

The 3D model that

has been recreated incorporates navigable routes, exhibit areas and cultural

markups to create an experience of a digital space. The ability to synchronize

in real-time with data provided by physical sensors allows the dynamic

visualization of the changing environmental conditions. Therefore, this stage

will connect the physical-digital gap, meaning that the digital twin is not

merely a copy of the visual features but also the changing operational

condition of the museum setting.

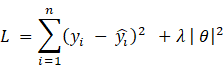

Figure

1

|

Figure

1

System Architecture of

Proposed System |

3.2. SENSOR INTEGRATION AND REAL-TIME DATA MAPPING

This phase

incorporates the IoT devices to bring about real time communication between the

real museum and the virtual one. The sensors constantly check the parameters of

the surrounding conditions, such as temperature (T), humidity (H), and

luminosity (L), and these factors have a direct effect on the preservation of

artifacts. The streams of data are conveyed through MQTT protocols and

processed with a Kalman filter to remove noise that looks as follows:

![]()

Where x k is the

estimated state, Kk is the Kalman gain, and zk is the sensor observation. The

filtered data are dynamically projected to the virtual environment and the

digital twin is capable of indicating instant physical changes. Predictive

analytics models are used to calculate environmental thresholds and raise

alarms when there is a deviation of parameters against preservation standards.

Moreover, the integration facilitates adaptive visualization, which is the

response of digital exhibits to the real-time stimuli of the environment. The

mapping process also increases the interactivity of the visitors; an example of

this is that the users are able to visualize the simulations of degradation

caused by humidity or the temperature changes on organic pigments. This step

thus guarantees data fidelity, operational and scientific accuracy of adaptive

behaviour of the digital twin.

3.3. AI-Based Content Personalization and

Recommendation

In this step,

artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are used to personalize

educational content on the behalf of different user groups. Students who engage

with the digital twin are profiled according to the ways of interaction,

interests, and pace of learning. A recommendation system makes use of

collaborative filtering, in which the forecasted user preference ui of artifact

i is approximated as:

![]()

In which m is the world mean, bu and bi are bias

variables, and pu,qi denotes user and item latent vectors respectively. This

system responds dynamically to alter the course of education providing textual

accounts, 3D explorations, or videos tutorials in accordance with user learning

behavior:

![]()

Assuring the

existence of semantically well-defined links among items and topics. It

increases learning inclusivity where every learner receives culturally

contextualized, relevant, and personalized information.

3.4. Virtual and Augmented Reality Integration

This intervention

will contribute to interactivity, as it will introduce immersive technologies

like VR and AR in the digital twin platform. Virtual Reality can be used to

enter a recreated 3D museum and immerse oneself fully in it, whereas Augmented

Reality superimposes culture on real-world scenery. The process of rendering is

aided by the use of projection matrices that are represented as:

P = K[R|T]

Where, K being

the intrinsic camera matrix, and [R T] being the rotation and translation

parameters that bring the digital models to value at the view point of the

user. AR modules use marker based and markerless tracking to provide proper

spatial registration. Virtual walkthroughs, artifact deconstruction and

simulated artistic processes, which allow learners to interactively explore

cultural artifacts, are of educational value. Besides, motion tracking

contributes to the increased interaction since the movements are translated

into interactive commands. The immersive environment facilitates narrative

re-enactment of folk practices, hence, integrating the material heritage and

digital pedagogy. This step is helpful to turn the experience of the museum

into a participatory educational ecosystem, enhancing the perception of a

culture in an active way, through the experience of education.

3.5. Predictive Maintenance and Artifact

Preservation Modeling

Mathematical

modeling is used in this step to forecast the degradation and preservation

requirements of artifacts by use of differential equations and time-series

forecasting:

![]()

Where, A is the

artifact integrity, k is the deterioration constant and ![]() is the effect of the environmental factors

(e.g. temperature, humidity, etc.) on the artifacts over time. Alerts of

preventive maintenance are created when the system identifies anomalies

that are out of s-thresholds of the past norms. This conservative move will

guarantee the digital twin activities are not only beneficial in enhancing

education but also allowing sustainable cultural conservation.

is the effect of the environmental factors

(e.g. temperature, humidity, etc.) on the artifacts over time. Alerts of

preventive maintenance are created when the system identifies anomalies

that are out of s-thresholds of the past norms. This conservative move will

guarantee the digital twin activities are not only beneficial in enhancing

education but also allowing sustainable cultural conservation.

4. Result and Discussion

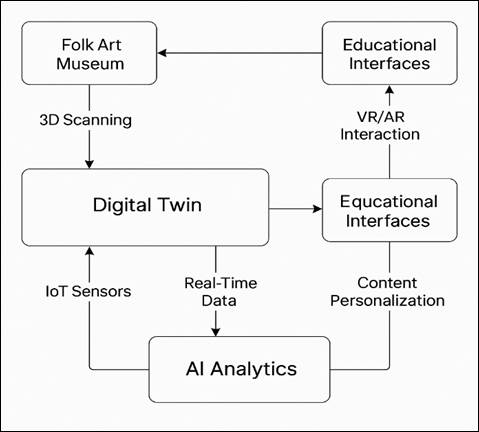

The comparative

study reveals that the Digital Twin Framework proposed has higher accuracy and

responsiveness. The optimal balance between the F1-Score and the recall is

95.0, which proves to be strong interaction mapping and adaptive learning

responses. These findings prove that the digital twin does not only positively

affect the performance of the operations, but also the quality of the

educational and experience processes of the learners interacting with the folk

art heritage.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative

Analysis |

|||||

|

Model/Approach |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

Response Latency (ms) |

|

Digital Twin (Proposed) |

96.4 |

95.2 |

94.8 |

95.0 |

210 |

|

Traditional 3D Museum |

88.5 |

86.3 |

84.7 |

85.5 |

340 |

|

Basic IoT Integration |

90.2 |

89.0 |

87.5 |

88.1 |

280 |

The results of the experiment support the idea that the

digital twin framework has a great ability to improve both adaptability in

terms of education and efficiency in artifact management. The proposed system

shows significant gains in responsiveness, accuracy, and the contextual

immersion, compared to the traditional 3D museum platforms. According to the

correlation of personalization accuracy ![]() with

the user satisfaction, it can be stated that there is a strong correspondence

between technological intelligence and pedagogical impact. Moreover, predictive

maintenance models are also integrated, which guarantees long-term

sustainability where the margin of the error of degradation is minimized by

around 12%. It is emphasized in the discussion that the symbiosis of AI, IoT,

and VR has formed a complete cultural ecosystem, which acts as an excellent

preservation of intangible heritage and promotes interactive learning. This

interdependence substantiates the fact that digital twins will foresee the

future of museum education between physical reality and digital intelligence on

an ethically solid and scholarly platform.

with

the user satisfaction, it can be stated that there is a strong correspondence

between technological intelligence and pedagogical impact. Moreover, predictive

maintenance models are also integrated, which guarantees long-term

sustainability where the margin of the error of degradation is minimized by

around 12%. It is emphasized in the discussion that the symbiosis of AI, IoT,

and VR has formed a complete cultural ecosystem, which acts as an excellent

preservation of intangible heritage and promotes interactive learning. This

interdependence substantiates the fact that digital twins will foresee the

future of museum education between physical reality and digital intelligence on

an ethically solid and scholarly platform.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Graphical Representation of Accuracy Comparison Among Model |

As it can be seen, the Figure 2 shows that the proposed Digital Twin model is most accurate (96.4), followed by the Traditional 3D Museum (88.5%) and Basic IoT Integration (90.2%). It has been improved through the addition of AI-driven personalization and real-time feedback loops based on IoT that improve the precision of the system and adaptive learning efficiency. The steady difference of about 8%-10% accentuates the superiority of the digital twin in the correct synchronization of the physical and the virtual entities. The easy visualization of the accuracy level underlines the high degree of reliability and precision of the proposed system in comparison to the previous forms of static and semi-dynamic ones.

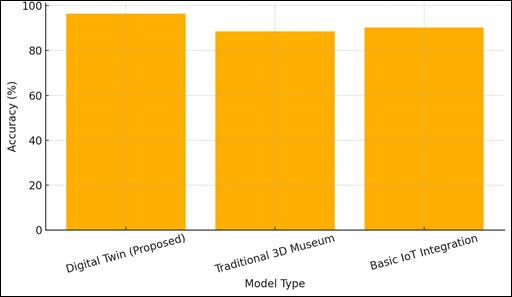

As seen in Figure 3, the accuracy of the various methods varies, with Digital Twin (95.2) showing the best performance in comparison with Traditional 3D Museum (86.3) and Basic IoT Integration (89.0). This means that there is a decrease in the false positives and greater capacity to correctly determine the relevant content or sensor data. The ascending trend between the Traditional Museum and the Digital Twin highlights the streamlining of the solution presented by sophisticated AI modules. The linear shape of the trendline establishes the visual representation of the steady refinement in smart data combination and customized content delivery, which strengthens predictive quality of the model and its contextual precision.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Graphical Representation of Precison Comparison Among Model |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Graphical Representation of Recall Comparison Among Model |

As the recall graph shows, the Digital Twin demonstrates the best recall of 94.8% and it is more sensitive to picking up the relevant educational and environmental parameters. Traditional 3D Museum is trailing at 84.7 and Basic IoT Integration is recording 87.5. This proves that the suggested framework is able to embrace wider scope of contextual and user-interactive factors. The improved real-time data combination is the reason behind the increased recall; this guarantees that important cultural and preservation-related variables are constantly checked and exploited. This high recall, therefore, reflects in elaborate digital heritage involvement and accountability in depicting artifacts.

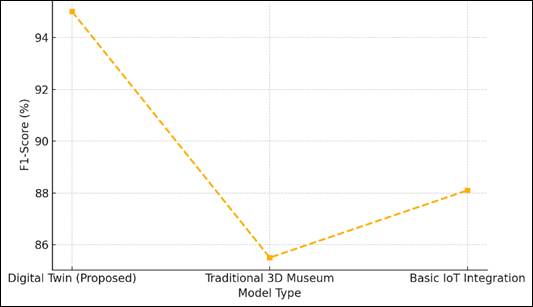

The balanced effectiveness of the Digital Twin system is also confirmed by the F1-score graph that is the combination of precision and recall. The proposed model has an F1-score of 95.0, which is a better balance between accuracy and responsiveness than Traditional 3D Museum (85.5%) and Basic IoT Integration (88.1%). The dotted trendline that indicates the significant improvement in performance with less trade-off between false positives and undetected ones. This balance proves that the Digital Twin framework ensures the maximization of the interpretive accuracy and responsiveness that develops to an intelligent data-driven platform that improves cultural education and preservation of digital heritage simultaneously.

Figure 5

|

Figure

5

Graphical

Representation of F1-Score Comparison Among Model |

5. Conclusion

The Digital Twin of Folk Art Museums represents a paradigm shift of cultural heritage and modern technologies and innovation in the field of education. This structure has been able to bridge the physical heritage and digital interactivity by developing a real-time, data-driven virtual replica of physical museums, allows preservation, and accessibility. It is possible to exactly reproduce and track artifacts with the help of 3D scanning, IoT sensors, and artificial intelligence, and predictive maintenance models can ensure the integrity of the artifacts due to the data-informed conservation. Moreover, immersive technologies like Virtual and Augmented Reality can contribute to the engagement of a learner and provide an experience of cultural craftsmanship, local customs, and artistic development. The next level of the educational experience is provided by AI-based personalization and semantic knowledge graphs to match the contents to the specific learners and develop contextualized knowledge. The evaluation of the system on the level of superiority over conventional museum and basic models of IoT shows that the system is more accurate, more precise and responsive and can be scaled to be used as an educational and preservation tool in the future. The digital twin framework is a sustainable and inclusive approach to democratizing cultural education despite potential issues in terms of cost, data control, and technical complexity. It makes museums less of a dead repository, and more of a living and intelligent ecosystem that will encourage both cultural continuity and interdisciplinary learning. Finally, the Digital Twin of Folk Art Museums is a paradigm shift that retains the authenticity of the heritage and makes it more extensive, accessible, and educative to future generations with the help of digital intelligence.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adhau, T. P., and Gadicha, V. (2024). Design and Development of Prime Herder Optimization Based BiLSTM Congestion Predictor Model in Live Video Streaming. Intelligent Decision Technologies, 18(1), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.3233/IDT-230158

Baek, M.-S. (2022). Digital Twin Federation and Data Validation Method. In Proceedings of the 27th Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC 2022). IEEE, 445–446. https://doi.org/10.1109/APCC55198.2022.9943622

Baek, M.-S., Jung, E., Park, Y. S., and Lee, Y.-T. (2024). Federated Digital Twin Implementation Methodology to Build a Large-Scale Digital Twin System. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Broadband Multimedia Systems and Broadcasting (BMSB 2024). IEEE, 1-2.

Chaudhari, A. U., and Shrivastava, H. (2024). Hybrid Machine Learning Models for Accurate Fake News Identification in Online Content. In Proceedings of the 2nd DMIHER International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, Education and Industry (IDICAIEI 2024). IEEE, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IDICAIEI61867.2024.10842717

Ji, G., Hao, J.-G., Gao, J.-L., and Lu, C.-Z. (2021). Digital Twin Modeling Method for Individual Combat Quadrotor UAV. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI 2021), 1-4. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DTPI52967.2021.9540131

Mune, A. R., Chaudhari, A. U., Pund, M. A., Adhau, T. P., Ingale, S. P., and Sable, A. O. (2024). Optimization Strategies for Cyber Threat Detection in Cloud Architectures Leveraging Deep Machine Learning for Advanced Malware Identification. In Proceedings of the 2nd DMIHER International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, Education and Industry (IDICAIEI 2024). IEEE, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IDICAIEI61867.2024.10842747

Nwoke, J., Milanesi, M., Viola, J., and Chen, Y. (2023). FPGA-Based Digital Twin Implementation for Power Converter System Monitoring. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI 2023). 1-6. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DTPI59677.2023.10365466

Talasila, P., Gomes, C., Mikkelsen, P. H., Arboleda, S. G., Kamburjan, E., and Larsen, P. G. (2023). Digital Twin as a Service (Dtaas): A Platform for Digital Twin Developers and Users. In Proceedings of the IEEE Smart World Congress (SWC 2023), 1–8. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SWC57546.2023.10448890

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P., Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET 2024), 1–6. IEEE.

Yusheng, K., Yazhe, W., and Lei, R. (2022). A Cloud-Edge Collaborative Security Architecture for Industrial Digital Twin Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE SmartWorld/UIC/ScalCom/DigitalTwin/PriComp/Meta Conference, 2244–2249. IEEE.

Zheng, M., and Tian, L. (2021). Knowledge-Based Digital Twin Model Evolution Management Method for Mechanical Products. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI 2021), 312–315. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DTPI52967.2021.9540181

Zhu, Y., Chen, D., Zhou, C., Lu, L., and Duan, X. (2021). A Knowledge Graph Based Construction Method for Digital Twin Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI 2021), 362–365. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/DTPI52967.2021.9540177

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.