ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Managing AI Tools in Traditional Art Curriculum

Sanchi Kaushik 1![]()

![]() ,

Dukhbhanjan Singh 2

,

Dukhbhanjan Singh 2![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Biswa Mohan Acharya 3

,

Dr. Biswa Mohan Acharya 3![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Varsha Bhosale 4

,

Dr. Varsha Bhosale 4![]() , Divya S Khurana 5

, Divya S Khurana 5![]() , Shivam Khurana 6

, Shivam Khurana 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (AIML), Noida

Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Computer Applications, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

4 Professor, Department of Information Technology, Vidyalankar Institute of Technology, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

5 Chandigarh Group

of Colleges, Jhanjeri, Mohali, Chandigarh Law College, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The swift

onslaught of artificial intelligence in the creative domain has disturbed the

long-held beliefs regarding the process of learning, rehearsing, and

mastering visual arts. Conventional art education has long been based on

embodied methods, including observation, repetition, sensual awareness, in

which a sense of touching charcoal or feeling a brushstroke is a constituent

of knowledge-making. The emergence of AI, starting with search engines of

generated references and composition evaluators and palette proposed, opens

up breathtaking opportunities and new contradictions. The study focuses on

the way AI may be managed, organized and integrated into conventional studio

based art education in an ethical way. It is a synthesis of the literature

published on digital art pedagogy, a study of emerging technologies changing

the concept of visual learning, and the development of a multi-layered

management structure of art schools. The study suggests that AI should be

placed in the role of a supportive mechanism that complements, but does not

substitute perceptual, manual and reflective practices that comprise the core

of the traditional art learning. An example is provided in the case studies,

implementation guidelines and a proposed evaluation rubric to demonstrate how

this integration can be operationalized without in any way making students

less creative or less skilled. The paper ends with summarizing the future

research opportunities, such as the long-term monitoring of AI-aided skill

development, cultural aspects of AI-generated imagery, and regulatory

frameworks governing how to keep the authenticity of the hybrid art-making

conditions |

|||

|

Received 30 January 2025 Accepted 21 April 2025 Published 15 December 2025 Corresponding Author Sanchi

Kaushik, sanchi.it@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6717 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Creative Pedagogy, Studio based Learning, AI-Assisted Critique, Visual Arts Teaching, Digital Augmentation, Art Skill Development, Human-AI Collaboration |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Traditional art classes have been a material dialogue space since time immemorial. A student is crouching over a drawing, calculating the proportions by the sweep of a drawn pencil at the length of an arm and by touching the contour of a drawing by feeling its rhythm instead of its geometry. But now this silent, haptic world is shot through with a new technologic presence as artificial intelligence is quickly taking over the creative industries. Artificial intelligence in the studio does not arrive as the noisy apparatus, but rather as a silent assistant, it suggests colors, creates references, or finds flaws or recreates the effect of lighting that would require hours to physically set up Wang (2024). With the advent of AI, a fundamental theme to art education is; how will the traditional curriculums based on the observational discipline and manual mastery be able to handle such mighty digital systems without losing their soul? The teachers of art in the whole world are excited but anxious. On the one hand, AI is promising to accelerate the ideation process and enhance the conceptual exploration. On the other it runs the danger of giving shortcuts to the practice of slow, deliberate apprenticeship which is what the studio practice should involve. Where teachers used to correct compositions by hand, students may now ask an algorithm to create twenty possible compositions in a few seconds Lee (2023). What is a day of labor is a few clicks, with which a weird compression of work, time, and training is introduced.

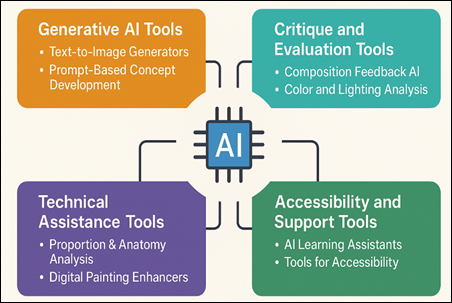

Figure 1

|

Figure

1

AI Integration

Areas in Art Classrooms |

This

study hypothesizes that AI adoption is not a villain or a redeemer of the

conventional education of art. Rather it is a substance that needs to be

moulded in mind, as clay in the hands of a sculptor. The AI is a matter that

needs pedagogical willfulness, ethics, and curriculum overhaul. It is not to

keep the tradition on the spot and to go full into the automation process but

to form a harmonious ecosystem, in which AI can complement learning and still

leave students with their creative agency and craft intuition Anggrellanggi and Sari (2023), Liao et al. (2025). The paper thus examines the past

historical trends surrounding technological changes in art, generalizes

existing literature, provides a structured management model, outlines various

classroom models, and gives a broadened approach to traditional art curriculum

in the future.

2. Practical Applications of AI Technologies in Art Design Education

The artificial intelligence has taken a curious place in the conventional art classroom. It is not a substitute to the easel or the odor of turpentine, but it is like some viewer that silently peeps in and at times makes some suggestions Zheng et al. (2024). To a large extent, AI can expand the studio experience, which provides students with novel means to compose, see patterns, and reflect on their decisions. In other respects, it upsets traditional theories of how artistic professionalism is developed. As a form of support, AI cannot be regarded as a digital shortcut, but rather a range of layers that can be used to direct, challenge, and enrich artistic education by being willfully employed. Visual exploration can be considered one of the greatest contributions of AI Marella (2025). Students can ask AI models to create different interpretations of a theme before touching a charcoal or pencil so that they can preview the possibilities. It does not overthrow traditional ideation but can give rise to more ideas. An example of this is a student trying to study the landscape, which can be done through AI to experiment with various lighting conditions or arrangements of space, and then apply these results to the hand-drawn drawings. This increases the imagination of the learner making him/her be able to see beyond the patterns UNESCO. (2024).

Table 1

|

Table 1 Key Functions of AI in Traditional Art Education |

|||

|

AI Function |

Description |

Benefit to Students |

Risk if Unmanaged |

|

Visual Ideation Almelweth

(2022) |

Generates variations, themes,

compositions |

Expands imagination and experimentation |

May reduce original thinking or

stylistic identity |

|

Technical Analysis Yefimenko et

al. (2022) |

Detects proportional, perspective, or

color errors |

Improves technique and visual accuracy |

Students may depend on AI instead of

training their eye |

|

Reflective Critique Buchori (2023) |

Provides feedback on balance, harmony,

or design |

Supports deeper critique and

self-evaluation |

Overthrust may weaken personal judgment |

|

Style Exploration Chiu et al.

(2022) |

Simulates historical or cultural styles |

Builds cultural literacy and contextual

skills |

Can result in stylistic imitation

rather than innovation |

When applied after creation, as opposed to within execution, these features enable students to identify technical flaws, at the same time, venturing into the manual practice. With practice, this feedback makes one keener in observation--which is the key ability in representational painting. The other new application of AI is in reflective learning. Lots of students are unable to explain the reasons of why their paintings seem not to be in balance or complete Yang (2020). Although imperfect, AI critique systems have the ability to point out to a particular issue or evaluate the work composed in relation to compositional principles. This gives a systematic point of departure of critique meetings and cultivates visual literacy. Notably, these criticisms should not take the place of the student but be secondary to his judgment.

Table 2

|

Table 2

Comparison of AI-Assisted vs Traditional Studio Processes |

|||

|

Process Stage |

Traditional Approach |

AI-Assisted Enhancement |

Recommended Balance |

|

Ideation Sheridan et

al. (2022) |

Hand-drawn thumbnails,

observation-based sketches |

Rapid concept generation through

text/image prompts |

Use AI after initial hand sketches |

|

Technical Development Tang (2021) |

Manual correction, instructor feedback |

Automated error detection or

suggestions |

AI as secondary, not primary, evaluator |

|

Color & Lighting Study |

Real-world observation, color wheels |

AI-based palette prediction or lighting

simulation |

AI for study references only |

|

Critique & Review |

Peer and instructor critique |

AI-supported visual analysis |

Combine AI insights with human critique |

The use of AI is also associated with accessibility and inclusivity. AI-assisted previews or instructions can be used to help learners with physical disabilities or little prior experience with art become confident. In the case of learners with different cultural backgrounds, AI may offer a more wide range of artistic events than a typical textbook.

3. Using AI as an Art Educational Tool in the Art Curriculum

The introduction of artificial

intelligence to the curriculum of art reinvigorates the learning environment in

a way that is more futuristic and, in some respects, more natural. AI, in this

case, is not as disruptive a novelty as it might be, but rather like a kind of

educational partner that allows students to see more, imagine more, and analyze

more. Instead of substituting the old ones, AI acts as a pair of eyes, fast,

analytical and unlazy, capable of assisting students in seeing the visual

structure of things, as well as choices related to creativity, more clearly. AI

may be used as an active source of references in drawing and painting courses Miralay (2022). Learners find it difficult to

visualize various lighting situations, temperatures of color, or composition

set ups in advance and commit them on paper. They will be able to look at other

possible scenarios and become more planning-oriented through AI-generated

prompts. This does not devalue the importance of sketches that are being done

by hand, on the contrary, it enhances the initial ideation process and makes

students get to the blank paper with a more definite intention. AI is therefore

an aid tool, which facilitates the thinking process of exploration of design

and does not replace it. AI can be used in the educational context as well as

in critique-based learning Xu and Jiang (2022). The conventional critique

meetings are based on oral peer and instructor feedback, which may be partial

or biased. Agency-based analysis tools though can point out inconsistencies of

perspective, color balance or tension of composition using objective detection

patterns, with the help of AI. These insights combined with human critique

enhance the student knowledge on visual language. Notably, the position of AI

in the form of critique should be seen as the guidance over the students, not

as the dictate; it will lead students in the right direction, but the final

decision will rest with individual choice and artistic purpose. AI may assist a

student to make a comparison between styles, motifs, and eras in historical and

cultural research Huang et al. (2024). To use an example,

style-matching algorithms driven by AI can match the work of a student to the

compositions of the Renaissance or find thematic resonance between the

individual work and the art movements that are thousands of years apart. This

type of comparison expands the historical imagination of the student and gives

them the ability to produce work that is informed by larger cultural histories.

In cases where students seek artistic identity, AI can show trends in their

personal output over time: through repeated shapes, colors, or plot lines, and

may assist them in defining their personal voice.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Summary of AI Tools, Their Functions, and Learning

Outcomes in Art Education |

|||

|

Category of AI Tool |

Representative Tools |

Primary Function in Art Curriculum |

Learning Outcomes for Students |

|

Generative Ideation Tools |

DALL·E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion,

Ideogram |

Generate visual variations, concepts,

compositions, lighting setups |

Enhances creative exploration, expands

ideation range, stimulates thematic experimentation |

|

Reference & Visualization Tools |

Magic Poser AI, Demotion, Osmania’s AI |

Provide pose references, anatomy

guides, motion studies |

Improves gesture drawing, proportion

awareness, and anatomical understanding |

|

Digital Painting AI Enhancers |

Adobe Photoshop AI, Clip Studio Paint

AI, Krita AI plugins |

Offer color suggestions, lighting

previews, symmetry corrections |

Strengthens technical control, color

literacy, and compositional accuracy |

|

AI Critique & Composition Analysis

Tools |

Canva AI Feedback, PaintJudge, Wix ADI |

Evaluate balance, contrast, focal

hierarchy, spacing |

Develops visual literacy,

self-evaluation skills, and critique vocabulary |

|

Color & Palette AI Tools |

Adobe Color AI, Khroma AI, Huemint |

Generate color harmonies, simulate

palette mood, test gradients |

Deepens understanding of color theory,

emotional tone, and color psychology |

|

Art History & Style Analysis Tools |

Google Arts & Culture AI, Smartify,

Magnus |

Identify art styles, compare motifs,

analyze historical influences |

Strengthens contextual knowledge,

cultural awareness, and historical mapping |

|

AI Drawing Assistants |

Clip Studio Pose AI, Procreate

Assistive Tools |

Provide pose correction, line

smoothing, perspective grids |

Supports early skill-building while

maintaining manual engagement |

|

AI Animation & Motion Tools |

RunwayML, EbSynth, Spline AI |

Convert drawings to animations, create

motion variations |

Builds hybrid skills in storytelling,

motion studies, and sequential art |

AI increases classroom accessibility. Visualization and feedback supported by AI can be of use with students whose exposure to various art materials was limited, or who undergo difficulties in mastering the basics of technical foundations. It democratizes access to knowledge of sophisticated critique and reference material of a professional level, allowing it to decrease skills differentials without destroying the feel of art-making.

4. Research Work Methodology

The research approach that will be used in this study is a multi-stage, structured approach aimed at investigating the possibility of implementing and managing AI tools in the context of conventional art education. Every step is based on the last one, so that the results are based on the pedagogical theory and practical realities in the classroom.

Step

1: Establishing the Research Context

The paper starts with a definition of the concept of the traditional art curriculum and determines the specific AI tools that are utilized in the visual arts teaching at the present day. These are generative image models, AI critique tools, palette recommenders, composition analyzers, and proportion-checkers. This step aims at explaining the scope of inquiry and making sure that similar terminology is used throughout the research.

Step

2: Comprehensive Literature Review

An in-depth analysis of the available literature is performed in the fields of art education, digital pedagogy, creative industries, and AI-assisted learning. The review includes historical technological shifts used in art classes, cognitive theory underlying the development of manual skills, the ethical debate of AI images, and the new research of AI-mediated creativity. This is done to offer some theoretical background and also to point out gaps that the research seeks to fill.

Step

3: Thematic Analysis of Pedagogical Challenges

Based on the information found in the literature, the study determines the main thematic issues namely overreliance, authorship issues, complexity in assessment, skills depletion, cultural bias, and equity problems. The themes are coded and grouped to inform the devising evaluation parameters of the proposed framework in the future. Such an analytical step is what will anchor the methodology based on actual educational issues and not necessarily on an assumption that is purely technological.

Step 4: Case Observation and

Mapping Classrooms

Sample art studios, workshops, and classrooms of digital-integration are observed (or based on documented case studies) to learn more about the current use of AI tools. It is observed to study the workflow of students, how they are confronted with a teacher, critique, and the proportion between manual and AI-assisted phases. The tendencies of these observations contribute to confirming the identified themes and to exposing practical limitations which educators have to deal with.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2

Stepwise

Methodology for the Study |

Step 5: Framework Design and Development

Upon the challenges and practice witnessed, a three-level management structure is created:

·

Pedagogical

Boundaries

·

Process

Transparency

·

Skill

Preservation

This includes the translation of theoretical ideas into practical instructions to teachers, curriculum planners and organization. This is the step that is used to synthesize research findings into a coherent structure.

Step 6: Expert Consultation

The

educators of art, studio instructors, and faculty teaching digital media are

also consulted to determine the feasibility of the presented framework. Their

feedback is examined to narrow the boundaries, scaffolding plans and assessment

principles. This consultative process will help to provide the ultimate model

with some real-life teaching setting.

Step 7: Testing with the

Hypothetical Scenarios

To

simulate the strength of the framework, imaginary classroom situations are

created- say, life-drawing, color-theory, sculpture pre-visualization and

composition-studies. The scenarios are each analyzed within the framework to

determine the way AI would be applied, limited, or incorporated. This stage

serves as a virtual validation stage.

The final research story is a synthesis of all the findings of the literature, observations, thematic analysis, expert input, and scenario analysis. This will involve recommendations, ethics and implications in future curriculum development. Transparency and replicability are achieved through the reporting step.

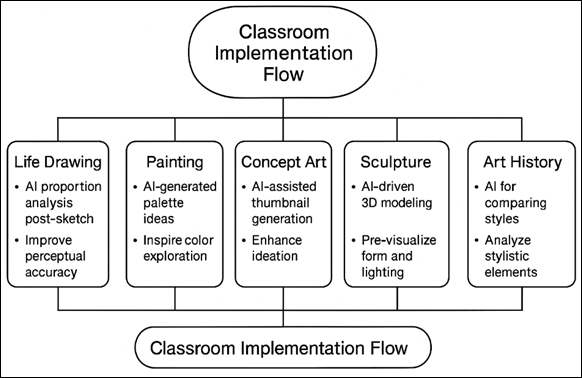

5. Classroom Implementation Models

The deployment of AI in conventional art classrooms needs

careful, adaptable approaches that will accommodate the nature of each field

and at the same time improve the education experience. Instead of introducing

AI as the universal tool, successful implementation considers each course as a

unique ecosystem, which has its rhythms, challenges and pedagogical objectives.

The use of AI in a manner that enhances the learning process rather than

substitutes the basic practice makes it a good companion that builds students

confidence, technical development and artistic autonomy. In life drawing studio

e.g., the stress is on observational discipline. This is because students still

develop sketches purely with the hand and are concerned with gesture,

proportion, and internal logic of the human form. It is not until after the

drawing session is done that they analyze the inconsistencies in proportions,

alignment, or imbalance in their compositions using AI tools. Such a slow

integration will make AI a reflective companion and not a live time corrective

tool. Students are taught to rely on their eyes initially and

consider AI as a mirror to uncover what they are blind to and help them perfect

their perception without compromising the slowness and embodied practice of

life drawing. Generative art color palette and lighting simulations can be

viewed as conceptual catalysts in painting courses. Rather than predetermining

the ultimate chromatic structure, AI provides other options of palettes that

students can read in whichever way they want, as they could flip through a book

of swatches or study the works of several painters at once. When considering

the proposals of AI as inspirational, but not prescriptive, students can not

only retain the right to make their own decisions about style, but also expand

their perception of the interaction between the colors, temperature contrasts,

and light effects on the atmosphere. The thumbnails created by the students are

used to define the narrative direction and the compositional hierarchy. It is

not until this stage of AI-assisted variation has been reached that they are

permitted to produce AI-assisted variations. This sequencing helps to make AI

enlarge the vision of the student without taking over the imaginary foundation

Figure 3

|

Figure

3 Implementation Model

for AI in Art Curriculum |

Table 4

|

Table 4

Implementation Timing and Pedagogical Rationale |

|||

|

Course Type |

AI Usage Timing |

Rationale |

Expected Learning Outcome |

|

Life Drawing |

After

completion of hand-drawn sketches |

Avoid premature dependence on digital

correction |

Stronger observational habits and

spatial error awareness |

|

Painting |

Before

painting, during planning |

Inspire exploration without dictating

decisions |

Broader color experimentation, improved

planning skills |

|

Concept Art |

After manual

thumbnails |

Preserve original ideation; use AI for

expansion |

Richer ideation sets, enhanced creative

diversity |

|

Sculpture |

Pre-studio

planning phase |

Visualize shapes before physical

execution |

Better understanding of form, shadow,

and mass |

|

Printmaking |

During early

design exploration |

Provide fresh patterns and textures |

Increased variety in motifs and surface

design |

|

Art History |

During

analytical sessions |

Support cross-era comparisons |

Enhanced historical literacy and visual

analysis |

AI-generated 3D models can be useful in pre-visualisation in sculpture studios. Students have a chance to study on how forms act in various lights or rotations or simulation of materials and then manually handle clay or mixed media. In the practice of art history and theory, AI is used as a tool of analysis, even in courses. The style-matching algorithms will enable the student to compare the motifs of the various epochs, trace the visual influences and study the common patterns of the composition in the various centuries. This enhances cultural sensitivity and also promotes the aspect of students looking at past historical works in new, comparative contexts. AI does not dominate, it broadens the creative space students can come up with. In the case of sculpture, a tool provided by AI 3D modeling is a pre-visualization aid that enables learners to test form and shadow first before actually casting. AI is applied in art history classes as an analytical engine to make comparisons of stylistic features between different periods. These examples show that AI can exist alongside the manual practice, provided that it is carefully designed as a pedagogical concept.

6. Case Study: Integrating AI Tools in a Traditional Drawing Studio

This case study will focus on considering how a traditional art institute incorporated the use of artificial intelligence tools into a first-year drawing studio without undermining the work of teaching manual skills. The course Foundations of Observational Drawing had traditionally been based on charcoal, graphite and live model studies. The trick was to make AI add to student education and still maintain the slow, physical discipline that is the pillar of classical training. The study was carried out over twelve week semester of 36 students. In the initial three weeks, students were exposed to traditional gesture drawing, contour studies, value scales, as well as, the practice of proportions. It was only following this base that AI tools were introduced. The main AI device was chosen a proportion-checking and line-analysis assistant which is an automated system that students could apply following their drawings but not during the process of their active drawing. This rule had made their eyes and hands be the main judges. Data used in this case study was created in house in a 12-week observation study in a first year course on drawing. The data has three types of data, including student performance indicators, AI-analysis feedbacks, and student qualitative reflections logs. There are 36 students in the dataset where each student gives weekly records in Week 1-12. Overall size of set of data: 1008 rows of data in all components.

Table 5

|

Table 5

Dataset Size Summary |

||

|

Dataset Component |

Total Entries |

Total Variables |

|

Student Performance Metrics |

432 entries (36 students × 12 weeks) |

5 variables |

|

AI Analysis Output |

288 entries (36 students × 8 AI-active

weeks) |

4 variables |

|

Reflection Logs |

288 entries (36 × 8 weeks) |

4 variables |

During week’s from four to seven, students were doing more in-depth figure studies. Thereafter they photographed their piece after every session and sent it to the AI system, which pointed out the mistakes of the alignment, discrepancies in the symmetry, and the uneven angles. Then, students were requested to compose a reflection by comparing their own critique with the observations made by the AI.

Table 6

|

Table 6 Case

Study Structure and Timeline |

|||

|

Week Range |

Activity Focus |

AI Involvement |

Purpose |

|

Weeks 1–3 |

Gesture drawing, contour lines, value

studies, proportion basics |

None |

Establish manual skill baseline and

strengthen observational habits |

|

Weeks 4–7 |

Figure drawing (long studies) +

still-life practice |

Post-practice AI proportion analysis +

AI lighting simulations |

Enhance accuracy, deepen understanding

of form and light |

|

Weeks 8–12 |

Final full-rendered drawing +

reflection logs |

AI used only for analysis and insight,

not corrections |

Encourage independent decision-making

and reflective practice |

This two-assessment plan enhanced metacognitive consciousness: students testified that they were more aware of their automatic errors including tilting shoulders excessively or axes off. Notably, the AI did not suggest corrections but merely indicated the existence of discrepancies retaining the responsibility to solve the problems manually on the part of the student.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Proportional Accuracy Improvement in Traditional vs. AI-Assisted Cohorts Over 12 Weeks. |

The figure demonstrates the increase in the proportional accuracy scores of two groups of students attending a 12-week drawing course. The trajectory of growth of the AI-integrated cohort is also much higher than the traditional cohort, with a minor lead in the first week but an increasing performance gap throughout the semester. Although the improvement of both groups is steady with repeated practice, the improvements of the AI-assisted students are greater, especially after the Week 4, when the AI-based post-practice analysis is introduced. The AI-cohort-curve steadily increases to the middle of 80s at Week 12 with great command of proportion and spatial evaluation. Conversely, the conventional cohort also ascends at a slower rate, and by the term finale, he/she reaches the low-70s. All in all, the graph indicates that technical development can speed up without interfering with the natural learning curve due to the structured and reflective application of AI feedback. They developed hand-drawn experiments in the conditions of the actual classroom light, and tried other shadows and accents with AI emulations. It was aimed at making them realize the behavior of light and not to reproduce the image produced by the AI. The oratory in classrooms also focused on the choice of art and not loyalty to the AI resource. Students had said they learned more deeply about the concept of form, shadow and contrast, but they still kept their way of interpreting style.

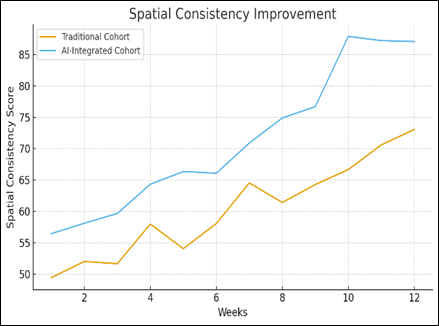

Figure 5

|

Figure

5

Spatial Consistency

Gains in Traditional vs. AI-Assisted Cohorts Across 12 Weeks |

The chart shows the change in the scores of spatial consistency of both the traditional cohort and the AI integrated cohort throughout the time frame of 12 weeks of instruction. Although the trend in both groups is favorable, positive, and upward, the AI-integrated group exhibits a significantly stronger upward curve. The AI-aided students begin at a slight advantage in Week 1 only to create a wide gap as the weeks roll on, especially after Week 5 when AI-aided visual analysis tools enter the reflective action plan. Their scores increase consistently, reaching its peak at Week 10 with a strong increase that demonstrates a strong improvement in depth perception, alignment accuracy and compositional stability. Conversely, the conventional cohort advances at a slower rate, and the skill acquisition is evenly distributed across time, as the conventional method of critique and practice. At the Week 12 level, the AI-integrated group continues to score the consistency of spatial perception at the mid-80s range, and the traditional cohort is close to the low-70s range. On balance, the graph emphasizes the speed of spatial awareness and structural knowledge development in students trained on AI-enhanced post-practices in comparison with the traditional training. In the last four weeks, the students had to perform a major project, the complete sketch in charcoal of a live model. Each student, along with their completed work, provided an "AI Reflection Log" documenting the time they used AI, what it taught them and how they incorporated or disregarded its advice. This generated a quasi-pedagogic effect: students were better able to express their visual reasoning and be more conscious of their choices of what to observe.

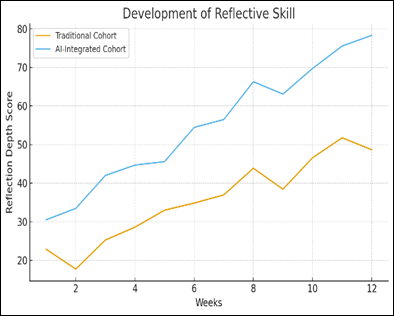

Figure 6

|

Figure 6

Reflective Skill

Development in Traditional vs. AI-Assisted Cohorts Over 12 Weeks. |

The graph 6 indicates gradual increase in the reflective skill of both kohorts within the 12 weeks period, but the AI-integrated group indicates a significant sharpe increase. Although the two groups start with a low reflection score, AI-assisted group scores increase fast after Week 5, and group 2 gains higher self-assessment, better awareness of errors, and more deliberate planning. By Week 12, they are scored in the 80s range, as opposed to the traditional cohort’s mid-50s. These findings are consistent with the general case study results: the proportional accuracy, the spatial consistency, and the overall confidence in the error diagnosis increase when students apply AI to work after they have completed their work and retained their personal artistic voice. The evidence indicates AI as a post-practice analytical tool and not as an active drawing aid can increase the technical awareness and depth of reflection and has no effect on creativity. There is no replacement of traditional pedagogy, but rather an enhancement and greater clarity with regard to intellectual artistic development.

7. Conclusion

The introduction of AI tools into the existing art education means a transformative opportunity with the help of mindful pedagogy and explicitly set boundaries. This paper illustrates that AI has the potential to enhance technical aptitude, enhance reflective learning and broaden creative exploration without reducing the haptic and experience basis of a studio practice. Its successful implementation requires sequencing, i.e., that manual work comes first and then AI comes in, as well as positioning AI as an analytical collaborator, and not a creative competitor. According to case study evidence, there are quantitative benefits of proportional accuracy, spatial reasoning, and self-evaluation with the use of AI in a controlled and post-practice ability. Meanwhile, the students still had stylistic personalities and claimed to feel more confident when it comes to their self-diagnosis. In drawing, painting, sculpture, concept art and art history, AI enhances learning by applying discipline specific strategies that prove that AI is flexible in its application throughout the curriculum. In the end, AI does not substitute the hand of the artist; it sharpens it and provides new vantage points that can be beneficial to improve the perception, understanding, and creative decisions. Planned AI can and will co-exist with conventional practices, and create a future where technology can assist, not replace, the human imagination.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Almelweth, H. (2022). The Effectiveness of a Proposed Strategy for Teaching Geography Through Artificial Intelligence Applications in Developing Secondary School Students’ Higher-Order Thinking Skills and Achievement. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 12(3), 169–176.

Anggrellanggi, A., and Sari, E. K. (2023). Opportunity to Provide Augmented Reality Media for the Intervention of Communication, Perception, Sound, and Rhythm for Deaf Learners Based on Cultural Context. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 13(4), 158–163.

Buchori, A. (2023). Virtual reality-based Virtual Lab Product Development in Developing Students’ Spatial Abilities using the Van Hiele theory Approach. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 13(4), 36–42.

Chiu, M. C., Hwang, G. J., Hsia, L. H., and Shyu, F. M. (2022). Artificial Intelligence–Supported Art Education: A Deep Learning–Based System for Promoting University Students’ Artwork Appreciation and Painting Outcomes. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–19.

Huang, K. L., Liu, Y. C., Dong, M. Q., et al. (2024). Integrating AIGC into Product Design Ideation Teaching: An Empirical Study on Self-Efficacy and Learning Outcomes. Learning and Instruction, Article 101929.

Lee, J. (2023). Practical aspects of AI collaborative art teaching and learning. Art Education Discussion, 128–155.

Liao, C.-W., Wang, C.-C., Wang, I.-C., Lin, E.-S., Chen, B.-S., Huang, W.-L., and Ho, W.-S. (2025). Integrating Virtual Reality into Art Education: Enhancing Public Art and Environmental Literacy Among Technical High School Students. Applied Sciences, 15(6), Article 3094. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15063094

Marella, V. C. (2025). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Traditional Art Education. arXiv Preprint.

Miralay, F. (2022). Examination of Educational Situations Related to Augmented Reality in Art Education. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 14(2), 141–157.

Sheridan, K. M., Veenema, S., Winner, E., and Hetland, L. (2022). Studio Thinking 3: The Real Benefits of Visual Arts Education. Teachers College Press.

Tang, Z. (2021). Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Art Education: Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 39(4), 583–597.

UNESCO. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Intangible Cultural Heritage (Policy Lab materials). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Wang, S. (2024). Enhancing Art Education Through Virtual Reality: The Impact of Virtual Art Museums on Junior High School Students. Research and Advances in Education, 3(9), 52–58.

Xu, B., and Jiang, J. (2022). Exploitation for Multimedia Asian Information Processing and Artificial Intelligence–Based Art Design And Teaching in Colleges. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing, 21(6), 1–18.

Yang, J. (2020). Artificial Intelligence in Art and Art Education: A Review of Recent Developments. Journal of Art Education, 43(2), 167–182.

Yefimenko, L., Hörmann, C., and Sabitzer, B. (2022). Teaching and Learning with AI in Higher Education: A Scoping Review. In M. E. Auer, A. Pester, and D. May (Eds.), Learning with Technologies and Technologies in Learning (Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Vol. 456). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04286-7_26

Zheng, W., Wang, Z., Wang, S., Wang, J., and Gao, Y. (2024). Innovative Tie-Dye Pattern Design Based on Sound Visualization Technology. Wool Textile Technology, 52(5), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.19333/j.mfkj.20230906606

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.