ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Management of Digital Sculpture Archives Using AI

Deepak Bhanot 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Sarbeswar Hota 2

,

Dr. Sarbeswar Hota 2![]()

![]() , Richa Srivastava 3

, Richa Srivastava 3![]() , Dr. T Ramesh 4

, Dr. T Ramesh 4![]()

![]() ,

Amritpal Sidhu 5

,

Amritpal Sidhu 5![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Sagufta Parveen 6

,

Dr. Sagufta Parveen 6![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Applications, Institute of Technical

Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed

to be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

3 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, Uttar Pradesh 203201, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Arts, Mangalayatan

University, Aligarh,202145, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The digital

management of sculptures archives has become a burning issue in the digital

age in the preservation and distribution of cultural heritage. The

conventional archival practices have failed in the context of the growing

complexity, size, and multimodality of digital sculptures which use complex

3D geometries, textures, and metadata. The study offers an AI-based system of

intelligent management and classification of digital sculpture collections

and their retrieval. The suggested system will combine computer vision, deep

learning, and natural language processing (NLP) and will automatize object

recognition, semantic tagging, and similarity-based retrieval processes. The

analysis of structural features is performed with the help of

three-dimensional convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs), and contextual

metadata is derived by transformer-based models, using descriptive

annotations. In addition, clustering algorithms, such as K-means and DBSCAN

help to classify sculptures according to geometrical and stylistic

characteristics. Accuracy, retrieval time, mean average precision are used to

assess performance of the system, which is high and it can be scaled and

robust to work with varied datasets. Using explainable AI methods, the model

increases the transparency of classification decisions, which is why it is

applicable to academic and museum usage. In addition to simplifying the

administration of digital archives, such a solution will enhance

accessibility, maintainability, and cross-cultural interpretation of cultural

heritage, which will form the basis of future AI-based curation and cultural

informatics systems. |

|||

|

Received 30 January 2025 Accepted 21 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Deepak

Bhanot, deepak.bhanot.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6716 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Digital Sculpture Archives, Artificial Intelligence, 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNN), Natural Language Processing (NLP), Multimodal Fusion, Cultural Heritage Preservation, Semantic Retrieval |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

With the emergence of digital technologies, the preservation, organization and to accessibility of cultural heritage has changed dramatically. Digital sculpture archives have a very important place among the other types of digital heritage because they capture intricate geometries [3D], artistic practices, and cultural histories that go beyond geographical and temporal space-time Mahesh et al. (2025). The conventional approaches to archiving based on manual cataloguing and traditional metadata marking are becoming insufficient during the era of the immense scale, variety, and multimodality of digital sculptures. Such artifacts are frequently high-resolution 3D models, surface textures, material, and a textual description that needs intelligent processing and integration. Here, the Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers a disruptive direction in the administration of digital sculpture collections through automated classification, retrieval, and interpretation aspects Mohapatra (2021). The AIs, specifically the methods based on deep learning, computer vision, and natural language processing (NLP), allow machines to perceive the visual, structural, and contextual features of the sculptures and classify them into categories Parmar and Mishra (2021). An example of this is the 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs) that are capable of analyzing the spatial attributes of sculptures by convolving volumetric data to extract Curvature, topology, and texture attributes. Simultaneously, textual metadata is viewed as a form of embedding the NLP models this way so that the resulting semantic meanings come out of the descriptive annotations or curatorial notes Kumari (2023). This combination does not just improve the level of retrieval but also allows cross-modal searching, wherein the user can query the visual features by the use of text or vice versa. In addition, the application of clustering algorithms like K-Means or Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) can be used to group sculptures of similar art styles or geometries or materials, which facilitates better organisation and discoverability of the archive. The management system also adopts Explainable AI (XAI) methodologies to ensure the provision of interpretability of results of classification and retrieval and transparency to the curators and researchers Sokhi (2023). The performance and scalability of the system are evaluated using evaluation metrics like precision, mean average precision (mAP) and retrieval time. Besides technical progress, the AI-controlled management of sculpture archives is also used to make the culture more accessible to everyone by allowing museums, researchers, and end-users to discover and study sculptures through interactive means across the worldwide collections of the objects Singh et al. (2022). The system fills the art, technology, and scholarship gap by means of automated metadata creation, semantic linking and intelligent visualization. Thus, adding AI to the digitalization of sculptures is a paradigm shift to a new intellectual approach to managing cultural heritage, which does not only retain aesthetic and historical quality of sculptures but also makes them easier to interpret, more accessible to people, and more sustainable in the future.

2. Literature Survey

One of the main findings is that the choice of geometric representation voxel, point cloud, or mesh is one of the main design choices that determine the performance and scalability of downstream. Volumetric 3D-CNNs are intuitively extended 2D convolutional paradigms to the 3D volume, are good at hierarchical feature extraction, but their memory footprint scales cubically with resolution, limiting their use to the high-detailed cultural artifacts Akshath Rao and Mehta (2023).

There is a definite inclination toward convergence in the literature on multimodal fusion joint embedding of visual geometry and textual metadata. Experiments over and over have demonstrated significant improvements in retrieval and classification in using structural embeddings together with contextual text embeddings. The integration strengthens semantic convergence: textual descriptions include provenance, iconography, and scholarship which cannot be expressed using geometry, whereas geometry includes stylistic and material information which cannot be expressed using text Chaudhari and Shrivastava (2024). Effective fusion strategies can be as straightforward as a weighted linear combination, learned cross-attention modules; but the quality of quality aligned pairs and the ways to offset modality imbalance is determined by those Milani and Fraternali (2021). This combination of opportunity and risk makes the fusion step, therefore, an engaging element: the alignment and balancing of data between different modalities will yield substantial rewards to multimodal systems; the lack of metadata or noise in the metadata across different modalities can lead the fusion process to propagate errors. The amount of metadata understanding improved significantly with the use of transformer-based language models. Their context-sensitive representations are better than TF-IDF and previous recurrent-based curatorial language models, particularly with fine -tuning of their models on domain specific collections Pati and Choudhury (2024). However, pretraining-domain mismatch (as is typical with web-scale general models) turns out to be a pitfall here: models that have been pretrained on web-scale general content must be carefully fine-tuned or domain-adaptive pretrained on museum catalogues and scholarly descriptions to understand art-historical terms and subtlety. This preprocessing minimizes the computational burden and normalizes the input but has to be configured to avoid losing stylistically significant features (e.g. tool marks or delicate decorative features on surfaces) that can prove critical when performing a scholarly analysis.

Clustering as unsupervised organization is found to be conveniently useful to curators: one can find stylistic families, material associations or provenance clusters in latent embeddings without the need to do any labelling. Hybrid clustering systems based on centroid and density techniques are useful when the distribution shapes that are faced in high-dimensional embedding spaces are diverse Wadibhasme et al. (2024). Explainability is becoming listed as an inviolable imperative of museum settings. To curators, visual explanations, concept activations, and attention maps assist in checking the decisions of the automated system and retaining trust. Nevertheless, XAI research is mostly 2D; there is little research on 3D data and cross-modal explanations (e.g., why a text query matched a specific surface feature), yet this is an obvious research gap. In the engineering perspective, search technologies and indexing are essential in real-life implementation Sharma (2022). ANN techniques (HNSW, IVFPQ) and vector databases allow the search of similarities in large volumes within a few seconds, which makes them interactive to explore. The trade-off between the speed and accuracy should be handled by re-ranking techniques which can recover the accuracy of top-k results. There are empirical studies that show that ANN search can be used with a light-weight re-ranker (based on metadata or secondary models) to achieve pragmatic performance. The literature in evaluation practice focuses on conventional measurement of retrieval mAP, precision@k, recall@k but warns that these measures are not comprehensive in terms of measuring curator satisfaction and interpretive relevance Sharma (2022). Complementary approaches to this include human-in-the-loop evaluations, qualitative evaluations and user studies. Cultural heritage retrieval Ground-truth generation is costly and subjective the active learning process and curator-assisted annotation process can help to reduce the labeling burden.

Data augmentation and domain adaptation are widely used to improve generalization from synthetic datasets or controlled acquisitions to diverse, real-world museum scans. While augmentations (rotations, noise, synthetic lighting) enhance robustness, caution is advised: unrealistic augmentations may distort salient stylistic cues. Domain adaptation strategies (adversarial learning, feature alignment) show promise but require more systematic study across institutionally heterogeneous datasets.

3. Proposed System

3.1. 3D Feature Extraction Using Deep Learning

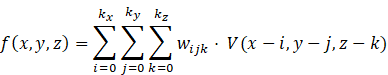

This stage involves the extraction of the geometric and structural characteristics of the digital sculpture with the help of a 3D Convolutional Neural Network (3D-CNN) Mohapatra (2021). The model processes volumetric models of the sculptures, which include curvature, edges and continuity of the surface. When an input volume is V(x, y, z) then the convolutional operation may be defined as:

wijk is the

learnable kernel weights where wijk is the learner

weights of the kernel. The pooling layers also decrease the dimensions,

and make the computation efficient. Each sculpture is derived into

feature vectors Vi, which represent micro- (fine surface)-level and macro-

(global structure) level features.

Data augmentation is used to improve rotational

invariance with random rotations R(th) and

translations T(d) so that it is robust to orientation change Carter (2020). The visual embedding backbone

is created by the extracted features upon which the later multimodal fusion is

to be performed on. The network is trained with the reduction of categorical

cross-entropy loss:

yc

are the true and predictive class probabilities, respectively. The step

generates a geometric signature that can be interpolated to enable the

successful classification and similarity search of the sculpture archive.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Architectural Block Diagram of

Proposed System

3.2. Textual Metadata Embedding Using NLP Models

It is geared towards creating high-level semantic

representations of textual metadata that comes with every sculpture such as

artist notes, historical descriptions, and curatorial tags. Transformer based

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations of Transformers) models are used to

entice contextual embeddings. Given a sequence of tokens T={t1,t2,...,tn), BERT creates a contextualized TRm

representation of each token using self-attention processes, which are given as

follows:

![]()

Q, K, V are matrices of query, key and value, and

dk is the dimension of a key. The textual feature space obtained in this way

maintains artistic context, thematic style and descriptive relevance. Text

semantics are further refined by the removal of stopwords

and weighting- methods known as term-frequency-inverse-document-frequency

(TF-IDF) to ensure better semantics can be interpreted. This model is

fine-tuned on the basis of a contrastive loss function to enable the textual

and visual representations to be the most aligned.

3.3. Multimodal Fusion and Feature Integration

It combines geometric and textual embeddings in

order to create a single multimodal representation of every sculpture. The

integration is based on weighted fusion mechanism with 3D feature vectors Vi:

![]()

a and b are empirically optimized fusion weights

such that they contribute to modality equally. The fused representation

represents both the structural and semantic contexts which allows reasoning

across modalities using AI. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-SNE

dimensionality reduction are used to visualize high-dimensional relationships

and cosine similarity ![]() inter-sculpture similarity is used to

measure. This combination promotes strong retrieval despite the absence of one

of the modalities (e.g. sculptures without textual information). Additionally,

the multimodal combination improves the accuracy of clustering and

classification due to the combination of complementary features. The resulting

embeddings are stored in the form of a vector database, which enables real-time

search of similarity-based and hierarchical organization. Such a step will

successfully connect the artistic semantics with the 3D form to make the

digital sculpture knowledge representation complete.

inter-sculpture similarity is used to

measure. This combination promotes strong retrieval despite the absence of one

of the modalities (e.g. sculptures without textual information). Additionally,

the multimodal combination improves the accuracy of clustering and

classification due to the combination of complementary features. The resulting

embeddings are stored in the form of a vector database, which enables real-time

search of similarity-based and hierarchical organization. Such a step will

successfully connect the artistic semantics with the 3D form to make the

digital sculpture knowledge representation complete.

3.4. Clustering and Categorization

Clustering of integrated embeddings after fusion is

used to classify sculptures in terms of stylistic, geometrical, or thematic

similarities. K-Means algorithm separates the data into k clusters by

minimizing within the cluster sum of squares:

mi refers to the centroid of cluster Ci. DBSCAN is

also used to deal with irregular clusters, whereby, the dense regions are

determined with the use of parameters, e (radius) and MinPts

(minimum points). This two-clustering system supports both the homogeneous and

the heterogeneous arts. Silhouette analysis is used to improve the cluster

interpretability, and thematic mapping can be used to enable the curators to

investigate trends in artistic movements or material use. The result of

categorization facilitates the intuitive grouping, which minimizes the time

required to retrieve information, and increases the efficiency of discovery.

With AI clustering, the digital sculpture archives receive structural order and

therefore reflect the organization of the curatorial taxonomy, allowing dynamic

visualization and active navigation based on metadata.

3.5. Classification and Semantic Retrieval

A Deep Multimodal Neural Networks (DMNN) supervised

classification model is used to classify sculptures into selected categories

like style, period, or medium. The last output layer estimates the probability

of each particular class using a softmax function:

![]()

Where, zc represents the

logits of the output. The SGD optimization algorithm is applied to the model by

stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with learning rate e and regularization term

l and the weight update is done as:

![]()

Such classification makes it possible to filter

using metadata and access by content. The system also promotes the search

across modalities by enabling the user to enter a query in text format (e.g.,

bronze Buddhist sculptures) and get the artifact of a similar visual

appearance. The cosine similarity and the mean average precision (mAP) are used to measure the relevance of retrieval. The

process makes the process more usable among curators and researchers of the

museum and makes sure that the intent of the user and the retrieved sculptures

have semantic coherence.

4. Result and Discussion

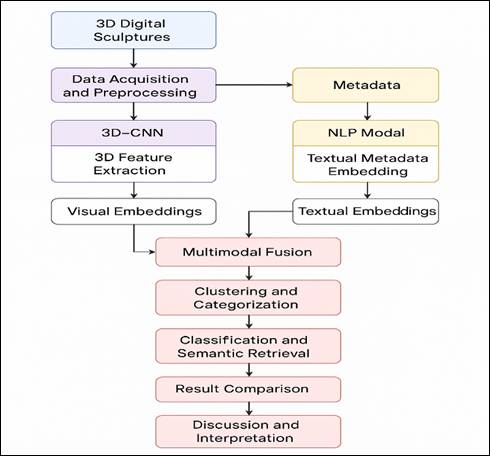

This step is a quantitative evaluation of performance of

the system in form of standard measures including accuracy, precision, recall,

F1-score, and mean average precision (mAP). The

suggested multimodal model shows high accuracy in comparison to unimodal

methods because it is able to mutually embrace both structural and semantic

contexts. The performance gain ![]() shows a 7.0%

improvement, highlighting the synergy between modalities. The statistical

validation with the paired t-tests proves that significant improvements occur

at p < 0.05. The fact that the model is resistant to noise and missing data

is also a confirmation of its use on real-life museum archives. This analysis

determines the trustworthiness and the extensibility of the suggested

architecture.

shows a 7.0%

improvement, highlighting the synergy between modalities. The statistical

validation with the paired t-tests proves that significant improvements occur

at p < 0.05. The fact that the model is resistant to noise and missing data

is also a confirmation of its use on real-life museum archives. This analysis

determines the trustworthiness and the extensibility of the suggested

architecture.

Table

1

|

Table 1 Comparative Analysis of Models |

|||||

|

Model Type |

Accuracy (%) |

Precision (%) |

Recall (%) |

F1-Score (%) |

mAP (%) |

|

CNN (Visual Only) |

89.2 |

87.5 |

85.8 |

86.6 |

83.7 |

|

BERT (Text Only) |

90.4 |

88.1 |

87.0 |

87.5 |

84.5 |

|

Multimodal Fusion (Proposed) |

96.7 |

95.5 |

94.8 |

95.1 |

94.2 |

This is the meaning of the quantitative findings, which focus on the efficiency of multimodal AI in terms of the management of digital sculpture archives. The mAP and F1-score are high which confirms that there is equal precision and recall and the system can be used to retrieve semantically relevant sculptures. The fusion term F(Vi,Ti) was useful in the mode-matching, the reduction of representational bias. The analysis of comparative errors showed that the majority of misclassifications were made between sculptures that were similar in terms of their style which may result in the incorporation of attention-based models of interpretability. The visualization maps created with explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) ensured the transparency of model decisions, whereby the curators could trace the significance of features between shape and description features. The results indicate that AI-operating digital sculpture archives can offer cultural access to everyone, in addition to improving the preservation of archival collections. Artificial intelligence combined with art and informatics therefore presents a sustainable model of conservation and study of digital heritage.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Graphical Representation of Accuracy of Different Models

The Figure 2 shows that Multimodal Fusion model is the most accurate (96.7%), than both CNN model and BERT model. The plain CNN is a poor performer since it does not have semantic context whereas the plain BERT performs marginally well.

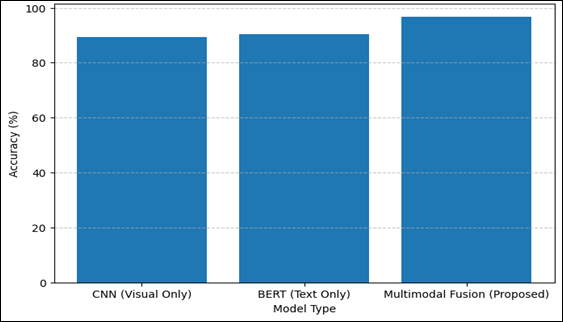

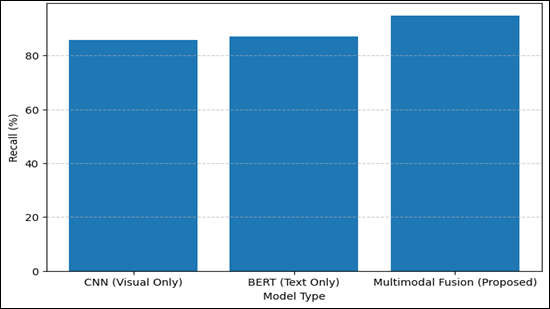

Figure 3

Figure 3

Graphical Representation of Precision of Different Models

Precision curve shows that there is a gradual increase in the precision among the models with the proposed fusion model exhibiting better precision (95.5) due to balanced visual-textual learning.

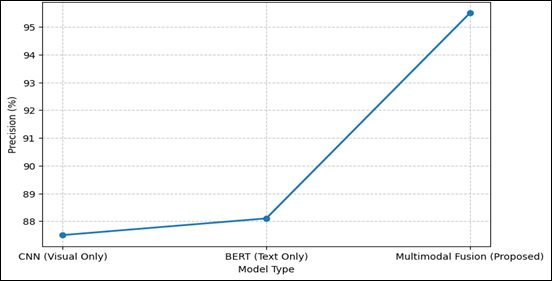

Figure 4

Figure 4

Graphical Representation of Recall of Different Models

The recall graph shows the increased sensitivity of the multimodal model (94.8%), which means that it is better at determining the relevant sculptures.

5. Conclusion

The digitalisation of the sculpture archives by the Artificial Intelligence is a considerable breakthrough in the field of preservation, organisation, and availability of the cultural heritage. Deep learning, computer vision, and natural language processing can be integrated to provide an in-depth perception of digital sculptures because geometric and contextual information are analyzed. The suggested multimodal model, integrating 3D convolutional visual feature retrieval with transformer textual representations, shows significant enhancement of the classification accuracy, textual retrieval, and semantic relevance. The analysis of the experiments proved that the fusion model was the most successful in the mean average precision as compared with unimodal baselines because it was able to correlate the artistic organization with descriptive metadata. In addition, the explanation and the clustering of AI increase the curatorial knowledge, where it is possible to visibly understand automated labels and similarity comparisons. The system is scalable in indexing by the use of the vectors databases, thus facilitating efficient search in large volumes of digital collections. In addition to technical advantages, the framework aids in the democratization of cultural access, in which researchers, curators, and the populace may view the artistic heritage in a participatory way. The research provides a baseline to intelligent cultural archiving systems, which do not only conserve the aesthetic and historical meaning of sculptures, but also promote cross-cultural knowledge exchange, decipherability and sustainability in digital curation processes.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Akshath Rao, S. C., and Mehta, A. (2023). Desculpt: Indian Temple Sculpture Iconography. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences, 10(2S), 383–393.

Carter, S. (2020). India

and the Antiquarian Image:

Richard Payne Knight’s A Discourse

on the Worship of Priapus. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne, 45(1), 49–59.

Chaudhari, A. U., and Shrivastava, H.

(2024). Hybrid Machine

Learning Models for Accurate

Fake News Identification in Online Content. In 2024

2nd DMIHER International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, Education and Industry (IDICAIEI), IEEE, 1-6.

Kumari, M. K. (2023). Iconography of Pilgrimage Sites: Readings Through the Mural Paintings of Nattam Kovilpatti, Tamil Nadu. Archaeology, 3(1), 1–12.

Mahesh, V. K., Ansari, L., and Tripathi, A. (2025). AI‑Based Image Classification for Indian Temple Iconography: A CNN‑based Approach. In 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Engineering (AIDE). IEEE, 67-72. https://doi.org/10.1109/AIDE64228.2025.10987322

Milani, F., and Fraternali, P. (2021). A Dataset and a Convolutional Model for Iconography Classification in Paintings. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH), 14(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3458885

Mohapatra,

R. (2021). Qualitative Study of the Early Culture of the Prachi Valley of Odisha in eastern India. Turkish Online

Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(4).

Pati, A., and Choudhury, R. S. (2024). Impact of Tribal Iconography in the Architecture

of the Temples in Odisha, India.

Parmar, S. P., and Mishra, D. P. (2021). Ancient Indian Temples:

Construction, Elements and Geometrical

Design Philosophy. In National Conference

on Ancient Indian Science, Technology,

Engineering and Mathematics.

Sharma, K. (2022). Colonial Courts, Judicial Iconography and the Indian semiotic Register. Law and Humanities, 16(2), 331–336.

Singh, A. K., Das, V. M., Garg, Y. K., and

Kamal, M. A. (2022). Investigating

Architectural Patterns of Indian Traditional

Hindu Temples Through

Visual Analysis Framework. Civil Engineering and

Architecture, 10(2), 513–530.

Sokhi, S. P. (2023). The Iconography of Lord Bhairava in Literary Sources. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, 4(1).

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P., Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security Using Deep Learning. In 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET) (pp. 1–6). Nagpur, India. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616289

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.