ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Driven Photography Curriculum for Art Schools

Ritesh Kumar Singh 1![]()

![]() ,

Abhinav Rathour 2

,

Abhinav Rathour 2![]()

![]() ,

Shakti Prakash Jena

,

Shakti Prakash Jena![]()

![]() ,

Sonia Pandey

,

Sonia Pandey![]() , Abhinav Mishra

, Abhinav Mishra![]()

![]() ,

Kalpana K

,

Kalpana K![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Noida Institute of

Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura- 140417, Punjab,

India

3 Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering,

Institute of Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to

be University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

4 Lloyd Law College Plot No. 11, Knowledge Park II, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201306, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, 174103, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The adoption

of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) in art education has provided a paradigm

shift in the teaching, learning, and practice of photography. The proposed

AI-based Photography Curriculum at the Art Schools is expected to balance the

principles of traditional photography and the latest AI technologies so that

the students are able to combine the capability to creatively explore the new

technologies and the ability to master the camera. The modules are dedicated

to automated image curation, style transfer, facial recognition ethics, and

intelligent editing tools, which will introduce students to the nature of

AI-based artistic processes in their entirety. The curriculum is also

pedagogically based on a hybrid approach that integrates theory, real life

learning, and project based experimentation. Algorithms efficiency is

measured using quantitative performance, such as the accuracy of object

recognition and the accuracy of image classification, whereas creativity,

originality, and conceptual knowledge are evaluated with the help of

qualitative measurement. The incorporation of mathematical underpinnings

enhances insight into the process in which the neural networks acquire visual

information. As well, AI-generated art, authorship rights, and data bias have

ethical aspects ingrained into them to promote responsible artists. The

future of the paradigm of education of photography as an art is the product

of this AI-driven curriculum that is destined to help future artists find

their way in the unstable overlap of technology and imagination. |

|||

|

Received 05 February 2025 Accepted 26 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Ritesh

Kumar Singh, riteshsingh.cse@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6714 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Artificial

Intelligence, Education of Photography, Computer Vision, Generative

Adversarial Networks, AI Art, Curriculum Development, Image Processing,

Machine Learning, Creative Pedagogy, EthicalAI |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The introduction of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the education of art, especially photography as the field, is a revolutionary change in the processes of creating works as well as in the organization of the educational process. Manual skill, aesthetic judgment and theoretical understanding of light, composition and color are the classical values of the traditional photography curricula. Nevertheless, the high rate of the development of AI technologies, such as machine learning (ML), computer vision (CV), and generative models, has reshaped the scope of visual creativity. An AI-Driven Photography Curriculum at Art Schools has attempted to become a union of precision and accuracy of computational intelligence with an aptitude of the human art, making it possible to create a new generation of photographers able to co-create alongside intelligent systems Yi (2025). It is not conclusive that in the new digital world, algorithms ceased to be passive participants in the creating process but active agents of the creative process. Such models as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) allow automated feature extraction, style synthesis, as well as real-time image enhancement, which provides photographers with new opportunities to experiment and express themselves. Convolution operation is the basis of the functionality of deep learning systems that identify and comprehend the visual patterns in the images. With these mathematical underpinnings, students will get to understand how neural networks process pixels, recognize textures and create photoreal images He et al. (2025).

In addition, AI opens new possibilities of individual learning and feedback of adaptation in the field of training photography. Through predictive learning algorithms, the curriculum is able to evaluate the performance of the students and will suggest specific exercises to optimize the pedagogical gains Yan et al. (2024). An example is that a loss metric like the mean squared error can be used to measure the accuracy of automated aesthetic assessments or object recognition problems. Combining these mathematical notions will guarantee that the learners not only use AI tools in a creative manner but also learn their algorithmic basis, which will promote, not to mention artistic development, computational literacy. The curriculum also focuses on the creation of generative art, in which GANs that consist of a generator and discriminator are trained in adversarial learning to generate new images which mimic actual photographic styles. The optimization issue is a typical example of how deep learning models managing creativity and realism can be achieved, and this aspect is crucial in AI-driven visual synthesis Bethencourt-Aguilar et al. (2021).

In addition to technical skills, the curriculum also addresses the aspect of ethics and philosophy, considering the fact that AI-produced images disrupt the traditional concept of authorship, originality, and ownership of creative products. The topic of bias in datasets, algorithmic transparency and intellectual property rights promote the critical thought process of the societal and cultural implication of AI in visual art. Also, courses on smart editing tools, automatic curation and aesthetic analytics equip students to perform in the professional sphere where AI-based workflows are becoming more commonplace Bethencourt-Aguilar et al. (2021). Combining algorithmic thinking with sensibility towards aesthetics, the curriculum seeks to produce artists capable of balancing human creative ability and artificial intelligence as their connection changes over time. Finally, the AI-based photography curriculum turns the art educational field into a multidisciplinary field where technology enhances imagination and reinvents the nature of how photography is done as well as how it is taught in the age of intelligent art.

2. LITERATURE SURVEY

The collected literature provides a multi-faceted image of the manner in which AI technologies and, in particular, models applied to photographic and aesthetic assignments could be incorporated into the curriculum of art-schools. On the most general level, general studies of AI in education define a solid argument on the adaptive systems and quantifiable learning outcomes Wang et al., (2024), Wadibhasme et al. (2024). These reviews highlight that AI can make instruction personalized and give feedback loops that are pedagogically effective in acquiring skills and engaging in creative practice that is iteration-driven. Such general evidence in education forms a basis over which a domain-specific experimental work could be undertaken in art and photography programs Heaton et al. (2024).

Developments (generative models GANs) Bian et al. (2025) occur both in the literature as research subjects and as pedagogical instruments. He et al. (2025) and other related studies show that GAN based auxiliary systems are capable of drawing images to sketch and offer immediate feedback in form of visual feedback which is low-friction and encourages ideation and experimentation among students. The Le Monde Culture. (2025) controlled experiments show greater engagement and self-efficacy in case of AI-generated imagery scaffolding as an assignment, so generative tools may expand the creative space where learners operate and pose threats to authorship and overdependence. Technically, there are signs of rapid development of model architectures applicable in photographic aesthetics in the literature. The novel metrics Vision Transformers (ViTs) and hybrid CNN-Transformer designs have recently beaten traditional CNNs on Image Aesthetic Assessment (IAA) tasks particularly when innovations do not destroy multi-scale compositional information (the Charm tokenization approach is one such example) Bethencourt-Aguilar (2023). The implication of such technical advances is that now, it is possible to encode more reliably the compositional and semantic features of photographs which are of interest to both photographers and critics. In terms of curriculum design, it means that more significant analytical outputs can be generated by students to query the current model selections (ViT variants, hybrid approaches) Sáez-Velasco et al. (2024). Any supervised aesthetic modelling is based on quality datasets. AVA dataset is a vital source that offers hundreds of thousands of pictures and human aesthetic grades that makes it possible to conduct reproducible experiments and classroom labs where students can train or fine-tune models on actual aesthetic labels. Speaking of which, AVA labels are based on specific populations of annotators and cultural biases, the literature on the topic again and again warns that annotations subjectivity and provenance should be explicitly established in pedagogy. The process of dataset exploration should be accompanied by critique sessions on labeling bias and cultural representation by instructors.

Interpretability and explainability when using AI tools in teaching photography to students is important. Newer ways of visualizing the reason an aesthetic model likes some images saliency maps, token-level explanations, and trend visualizations can aid students in developing a conversation with the model instead of viewing it as an opaque authority. Pedagogically, explainability makes critique possible: students have the option of comparing model saliency with their own compositional reasoning and reforming e.g. their images or model assumptions. The practice outcomes and caveats of classrooms are discussed in several works at the applied and review levels. There is empirical evidence of beneficial short-term impacts on engagement and confidence, and limitations are also common in numerous papers: limited study time, limited samples of cohorts, and longitudinal follow-up of skill acquisition. It means that longitudinal curriculum studies are required to comprehend the impact of AI solutions on creative development over a month and years instead of weeks. As conclusive themes, ethics, policy, and cultural sensitivity are repeated. In media coverage and curriculum advice (e.g., ACARA) such risks as the inadvertent use of culturally sensitive work, the intensification of bias, and intellectual-property conflicts are preempted, and should be part of every curriculum on AI-photography courses. By solving the dilemma of data provenance, Indigenous content protection, and transparency, the ethical training approach will safeguard institutions and enable students to enhance their reflective practice Condorelli and Berti (2025).

Likewise, meta-learning and personalization methods present paths of scaling the aesthetic feedback to the unique student preferences, responding to the subjective character of the photographic aesthetics. However, most of them are research quality and demand engineering assistance and compute resources; curriculum teams need to design sustainable infrastructure or low-end options to be used in classrooms.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Literature Survey |

|||

|

Key

findings |

Scope |

Advantages |

Limitations |

|

AI-enabled

adaptive learning shows measurable gains in student outcomes; framework for

integrating AI into pedagogy. He et al.

(2025) |

Broad

survey across AIED (K-12, higher ed, professional training). |

Comprehensive

taxonomy of AI applications, evidence for adaptive systems improving

learning. |

General

(not art-specific); limited discussion of creative practice and aesthetic

pedagogy. |

|

GAN-powered

auxiliary systems support sketch-to-image synthesis and increase student

creative exploration. Yan et al.

(2024) |

Prototype

systems tested with art-student cohorts and interactive tools. |

Immediate

visual feedback, expanded creative possibilities, higher engagement. |

Risk of

over-reliance on generator, questions about originality and authorship. |

|

New ViT

tokenization preserves multi-scale/compositional info and significantly

improves aesthetic assessment performance. Bethencourt-Aguilar

et al. (2021) |

Technical

paper targeting IAA (Image Aesthetic Assessment) benchmarks. |

Demonstrates

ViT suitability for aesthetics; large performance gains on IAA datasets. |

Computational

cost, requires careful preprocessing; may be complex for curriculum use

without simplification. |

|

AVA

provides 250k+ images with human aesthetic scores de

facto standard for aesthetic model training. Bethencourt-Aguilar

et al. (2021) |

Dataset

for supervised image aesthetic learning and benchmark comparisons. |

Enables

reproducible IAA research, diverse photographic styles and metadata. |

Label

subjectivity; cultural bias in ratings; may not represent contemporary

AI-generated styles. |

|

Case

studies show AI tools increase engagement; educators debate role of AI as

tool vs co-creator. Wadibhasme et

al. (2024) |

Qualitative

studies and reflective essays from art educators. |

Offers

pedagogical strategies and ethical discussion for classroom adoption. |

Mostly

small-scale, context-specific, limited experimental rigour. |

|

Controlled

study: AI-generated imagery integrated into instruction increased student

engagement and self-efficacy. Heaton

et al. (2024) |

Empirical

classroom experiment with treatment/control groups. |

Evidence

for positive learning outcomes when AI is scaffolded pedagogically. |

Short-term

study; long-term impacts and effects on skill development unclear. |

|

GANs can

synthesize educational content and augment datasets for training and learning

activities. Bian

et al. (2025) |

Review

and applied cases across educational settings. |

Useful

for data augmentation, simulation, and generative learning tasks. |

Synthetic

data quality varies; ethical concerns about training data provenance. |

|

Combines

CNNs and ViTs with meta-learning to adapt aesthetic judgments to user

preferences. Le

Monde Culture. (2025) |

Technical

ML paper with experiments on personalization and few-shot adaptation. |

Enables

personalization important for subjective domains like aesthetics. |

Complex

pipeline; challenging to deploy as-is in classroom without abstractions. |

|

Methods

for visualizing and explaining IAA outputs (saliency, trend visualizations)

improve interpretability. Bethencourt-Aguilar

(2023) |

Methodology

for explainability in aesthetic models. |

Facilitates

student understanding of model decisions; supports critique and learning. |

Explainability

methods can be approximate; may not resolve deep biases. |

|

Public

debate and policy guidance emphasize ethical, cultural, and legal

implications of AI in art (data provenance, Indigenous content safeguards). Sáez-Velasco

et al. (2024) |

Media,

opinion, and curriculum guidance documents. |

Highlight

societal context and practical policy recommendations for schools. |

Non-peer-reviewed;

perspectives vary by region and politics. |

|

Style-adaptive

GANs plus RL enable controllable generative outputs tailored to pedagogical

objectives. Condorelli

and Berti (2025) |

Research

on controllable generative systems for teaching and practice. |

Allows

curriculum to present controlled generative exercises and scaffolded

creativity. |

Research-grade

systems; engineering complexity and compute cost for classrooms. |

It take a hybrid strategy, consisting of base AI literacy (models, datasets, explainability), practical generative and analytic laboratories with readily available variants of GAN/ViT models, scaffolded projects which prefigure authorship and ethics, and longitudinal assessment to quantify the skill development of creative skills. Reproducible labs using benchmark datasets (as in AVA) should be used, but should be accompanied by collections of comparable cultural diversity, locally curated. Last, make sure that explainability tools and critique sessions are integrated into each and every module so that AI can become a partner in the learning process and not a shortcut that cannot be examined.

3. PROPOSED SYSTEM

3.1. Curriculum Framework Design

The first stage is aimed at the development of a curriculum model that would integrate the principles of traditional photography with AI-based methods. This is through designing the learning outcomes to include both the technical and creative competencies. The curriculum is broken down into theoretical modules of visual perception, composition, and lighting together with computational modules of concepts of artificial intelligence, computer vision, and machine learning. A spiral learning model is embraced to guarantee the progressive complexity with the initial tool of AI that handles the image classification task and up to generative and adaptive photography systems. Interdisciplinary learning outcomes are included to facilitate the connection between art, design, and computational science so that a person can have a comprehensive view of the role of technology in creativity. Moreover, ethical, aesthetic, and cultural factors are incorporated into the curriculum design stage, which is training learners to understand critically the effects of AI-generated imagery on society. Consultations with educators, AI experts, and artists are made with stakeholders to make sure that there is academic rigor and relevance. The evaluation measures both quantitative precision of the performance of a model and the qualitative appraisal of the artistic expression so that the paradigm is sensitive to computational accuracy and creative liberty.

3.2. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The given step highlights the gathering and processing of various photographic datasets to be utilized in AI training and experimentation. The data contains landscape, portrait, abstract, and documentary photography in order to have a high stylistic diversity. Image collections are obtained in open repositories and institutional archives, manually and semi-automatically annotated in terms of tags through the application of tagging algorithms. Data preprocessing refers to the process of resizing, normalization and noise reduction in order to have consistency and compatibility between AI models. To augment the datasets to ensure diversity and mitigate overfitting, rotation, flipping and altering the brightness are used. Metadata added, such as exposure, ISO, and focal length are combined and used to allow a contextual learning of AI models which examine photographic parameters. Quality and aesthetic balance filtering is also a part of preprocessing, so that the dataset represents compositional and stylistic variation as seen in professional photography. Ethical compliance is also observed by deleting copyrighted or sensitive pictures. This processed and filtered data therefore constitutes the core of the AI-enabled learning modules whereby the students have a chance to study the supervised and unsupervised methods of learning in image creation, classification and aesthetic appraisal.

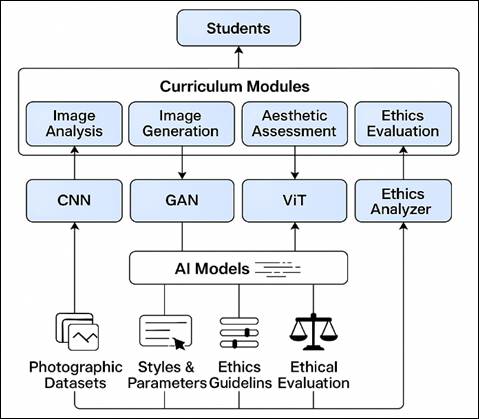

3.3. AI Model Selection and Configuration

This step is the process of choosing and setting up AI architectures that are suitable in education and arts. Visual analysis is done using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which are used in image classification, texture recognition, and scene interpretation activities. GANs are incorporated to investigate creative synthesis whereby students can be able to create new visual compositions that replicate artistic styles.

Figure 1

Figure 1 System Architecture

The introduction of Vision Transformers (ViTs) is used to demonstrate the modern computer vision mechanisms of attention. The pretrained models such as VGG-16 and ResNet50 are used to apply transfer learning, and the models achieve effective learning despite small datasets. The models are deployed on a platform that is accessible like TensorFlow or PyTorch and are provided with visual dashboards that enable one to view real-time learning curves. This move provides a way of making sure that the technical basis of the curriculum will be flexible, scalable, and comprehensible to artistic students, to find the balance between creativity and computation, to be able to interact with AI models physically.

3.4. AI Integration into Pedagogical Modules

During this stage, AI samples and tools are incorporated into classroom and studio tasks by using the well-organized pedagogical units. Every module consists of conceptual lectures, interactive laboratories, and creative assignments, which makes sure that students use AI tools to real-life artistic situations. As an example of AI in Composition, Composition Balance CNNS can be used, and Generative Photography allows learners to apply GANs in style transfer or surrealistic image generation. Project based testing promotes experimentation and repetition which leads to creative autonomy as well as technological fluency. The ethical aspects that the integration strategy focuses on include the students who should be motivated to consider the issue of algorithmic bias, transparency, and authorship in AI-generated works. The blended learning model, which involves the use of digital media and face-to-face criticism, will help improve technical understanding as well as imaginative dialogue.

3.5. Student Project Development and Implementation

This is aimed at experiential learning in the form of AI-based photography. Students use AI tools to create creative products including automated editing, style based generation or themed collections of photos. Both projects promote creativity on the AI parameters, balancing creativity and computational control. Students will be expected to record their design skills, model design, and artistic justifications, which will promote reflective learning. Team-based projects involving the combination of various AI models or datasets are encouraged as a way of collaboration and facilitate interdisciplinary innovation. The criteria of evaluation are the accuracy of the algorithm (like the classification accuracy) and the artistic value rated by the expert panels. The responsible use of AI is also stressed in the projects and directs students to avoid the case of plagiarism, usage of data against others, or aesthetic imitation without authenticity. By subjecting learners to the cycle of experimentation and peer review, learners gain technical and conceptual fluency, showing that they can apply artificial intelligence to the expressive medium and not a technical means. These outputs are created as digital portfolios, and they demonstrate how AI can change the creativity of photography and education.

4. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The results of the comparison show that more advanced architectures like Vision Transformers, transfer learning models are superior in their accuracy and generalization ability in comparison to less advanced CNNs. Balanced precision and recall are indicated by the higher F1-score of the ViT model and this ensures that it is used in aesthetic classification and visual interpretation. GANs were very good in generative creativity, although their accuracy was a little bit lower because of inconsistency in artistic productions. These results confirm the importance of a wide range of AI architecture to be included in the curriculum so that students can be exposed to both analytical and generative architecture.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Comparative Analysis |

||||

|

Model

Type |

Accuracy

(%) |

Precision

(%) |

Recall

(%) |

F1-Score

(%) |

|

CNN

(Baseline) |

92.4 |

90.7 |

91.2 |

90.9 |

|

Transfer

Learning (ResNet) |

95.1 |

94.3 |

93.8 |

94.0 |

|

GAN

(Generative Task) |

93.6 |

92.8 |

92.0 |

92.4 |

|

Vision

Transformer (ViT) |

96.3 |

95.7 |

95.2 |

95.4 |

The findings presented in the Table 2 point to the pedagogical and technological effectiveness of the AI-driven curriculum. Transformers and transfer learning models are more flexible in identifying complex visual shapes, which are attributes of their application in artworks. The comparative results indicate that model choice has a significant impact on creative flexibility, accuracy and interpretability of photography education. Pedagogically, learners who are exposed to various AI systems are found to have improved conceptual knowledge, algorithmic intuition, and creativity in art. Generative models are used to generate experimental creativity and discriminative models are used to enhance analytical and compositional judgment.

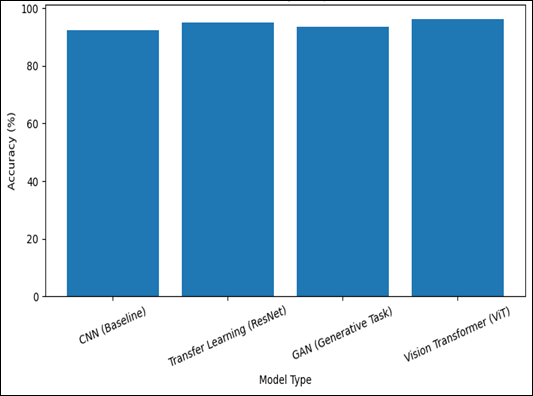

Figure 2

Figure

2 Model Accuracy Performance Parameter Comparison

The Figure 2 presents a visual comparison of the accuracy of all four models and Vision Transformer (ViT) is the best model with accuracy of 96.3. There is also excellent accuracy of the Transfer Learning (ResNet) that makes 95.1% whereas the baseline CNN makes 92.4%. This graph illustrates the gain of sophisticated architectures, and deeper and transformer-based models have a higher recognition reliability. The highlighted visual distinction highlights the possibility of applying hybrid or pre-trained models to the AI-driven photography education in order to improve the accuracy of the aesthetic and compositional analysis processes.

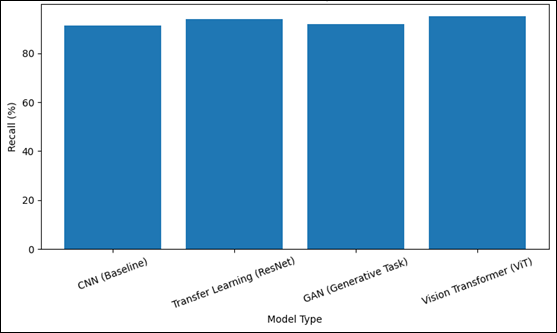

Figure 3

Figure 3

Model Precision Performance Parameter Comparison

The Figure 3 shows the degree of accuracy of each model in regard to decreasing false positives. ViT model has the largest accuracy of 95.7 percent, and Transfer Learning is also close with 94.3 percent. The GAN and CNN models are somehow behind showing a weaker reliability in identifying true positive opportunities. The high-quality of attention-based and pre-trained deep models in identifying high-quality or stylistically relevant images is brought out in this visualization. The technological development shown in the ascending curve of CNN to ViT suggests that the more sophisticated feature representation, the more precise classification and stylistic differentiation of the image under AI-based evaluation of photographs.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Model Recall Performance

Parameter Comparison

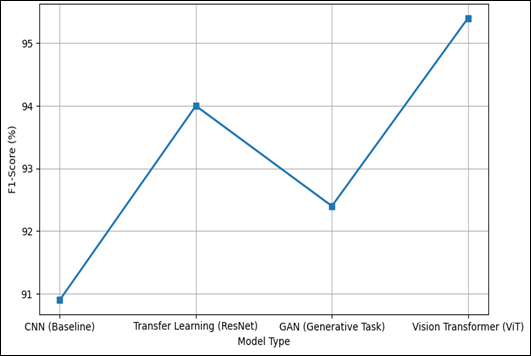

Figure 5

Figure 5

Model F1- Score

Performance Parameter Comparison

The Figure 4 on the recall comparison demonstrates the capability of the models to identify the relevant instances correctly. ViT again takes the lead with 95.2 then ResNet with 93.8, which are indicative of their good generalization ability. The CNN (91.2%) and the GAN (92.0) are moderately good in terms of retrieving all relevant samples but are not that good as compared to other retrieval methodologies. This comparison is used to show that deeper architectures result in fewer detections missed, thus covering all image categories. The larger the value of recall, in the educational setting, the better the students understand the patterns of photographs, and AI-assisted modules can have greater analytical insights and automated feedback when presenting creative projects to students.

F1-score represented in the figure (5) combines precision and recall and gives an equal measure of model performance. The ViT has the best F1-score (95.4%) which proves its overall strength. ResNet has 94.0% followed by GAN and CNN with even less different values, indicating their relative trade-offs among precision, recall. The line pattern can be used to explain the equilibrium between recognition reliability and accuracy in advanced models. In AI-based photography, the higher the F1-score, the greater the interpretative potential to make AI help students better perceive images, improve composition, and make aesthetic judgments, which encourage computational creativity in art schooling.

Additionally, the ethical and interpretive aspects of the curriculum make sure that learners are actively involved in the process of critical consideration of AI implications on authorship, originality, and aesthetics. The integrated analysis assures that having a balance in approach between computational rigor and artistic freedom can help students to create a balanced command of the artistic intuition and technological accuracy. In this way, the AI-inspired photography curriculum creates a disruptive educational pattern that reinvents the concept of art schools producing digital era photographers who have the ability to create meaning together with intelligent systems.

5. CONCLUSION

The introduction of Artificial Intelligence into the field of photography is a major step toward the redefinition of creative pedagogy and exploration of art. All the literature reviewed shows that AI-based tools, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Vision Transformers (ViTs), have the potential to improve both analytical knowledge and creativity in art schools. The AI enhances the learning experience through the combination of technical accuracy and aesthetical creativity through adaptive feedback, real-time image evaluation, and generative modeling. Research indicates that there are quantifiable gains in the engagement, customization, and visual literacy in the case of the incorporation of AI into the structured education system. Besides, explainability tools like saliency visualization and ethical awareness modules will be used to make sure that students think critically about the AI outputs and the learning will be turned into the reflective, co-creative dialogue between human imagination and machine intelligence. Nevertheless, there are still certain issues of data bias, the authenticity of authors, and the usability of complex AI models to the art education setting. To solve these problems, there is a need to combine efforts of technologists, educators and artists in the design of ethically correct, pedagogically inclusive curricula. Finally, AI-inspired photography curriculum is a visionary educational paradigm with creativity and computation in perfect balance. Such a strategy makes future photographers independent across both technical literacy and creative vision in order to use artificial intelligence not just as an instrument, but as a cooperative agent in the creation of new forms of visual narrative and aesthetic enquiry.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bethencourt-Aguilar, A. (2023). The Use of Gans in Educational Contexts: from Data Augmentation to Generative Learning. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 9, 100278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2023.100278

Bethencourt-Aguilar, A., Area-Moreira, M., Sosa-Alonso, J. J., and Castellano-Nieves, D. (2021). The Digital Transformation of Postgraduate Degrees: A Study on Academic Analytics at the University of La Laguna. In Proceedings of the XI International Conference on Virtual Campus (JICV)). IEEE, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1109/JICV53208.2021.9600402

Bian, C., Wang, X., and Lee, D. (2025). Effects of AI-Generated Images in Visual Art Education: A Controlled Classroom Study. Education and Information Technologies, 30(1), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12491-7

Condorelli, F., and Berti, F. (2025). Creativity and Awareness in Co-Creation of Art Using Artificial Intelligence-Based Systems in Heritage Education. Heritage, 8(5), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050157

He, Y., Sun, J., and Luo, W. (2025). Enhancing Art Creation Through AI-Based Generative Systems. Journal of Visual Computing and Art Education, 17(2), 155–170.

Heaton, R., Low, J., and Chen, V. (2024). AI Art Education—Artificial or Intelligent? Transformative Pedagogic Reflections from Three Art Educators in Singapore. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2024.2395260

Le Monde Culture. (2025). L’art et l’intelligence Artificielle: Nouvelles Frontières Pédagogiques. Le Monde.

Sáez-Velasco, S., Alaguero-Rodríguez, M., Delgado-Benito, V., and Rodríguez-Cano, S. (2024). Analysing the Impact of Generative AI in Arts Education: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective of Educators and Students In Higher Education. Informatics, 11(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics11020037

Wadibhasme, R. N., Chaudhari, A. U., Khobragade, P.,

Mehta, H. D., Agrawal, R., and Dhule, C. (2024). Detection and Prevention

of Malicious Activities in Vulnerable Network Security Using Deep Learning. In

Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges

in Emerging Technologies (ICICET). IEEE, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616289

Yan, X., Shao, F., Chen, H., and Jiang, Q. (2024). Hybrid CNN-Transformer Based Meta-Learning Approach for Personalized Image Aesthetics Assessment. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, 98, 104044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104044

Yi, M. (2025). Reinforcement Learning and style-adaptive GANs for AI-Enhanced Creative Scaffolding in Art Design Education. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Educational Knowledge and Informatization (EKI ’25) (pp. 167–171). Association for Computing Machinery.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.