ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

From Exclusion to Belonging: Assessing Women's Perception of Public Open Spaces

Arushi Malhotra 1![]()

![]() ,

Rawal Singh Aulakh 2

,

Rawal Singh Aulakh 2![]()

![]()

1 Research

Scholar, Department of Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University, India and

Faculty, School of Design and Architecture, Manipal Academy of Higher

Education, Dubai, UAE, India

2 Faculty, Department of Architecture, Guru Nanak Dev University, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Public open

spaces are integral to urban landscapes, offering chances for interaction,

recreation, and community engagement. However, their design and management

profoundly influence diverse user experiences and perceptions. Women's

experiences of public open spaces are often shaped by a complex interplay of

factors, including social norms, safety concerns, and the physical

environment. This research aims at deciphering the complex relationship

between women, gender, and their perceived place within these spaces. Drawing

on qualitative research methodologies including Ethnography, on site

semi-structure interviews and site observations, the study scrutinizes

women's perceptions and interactions in these spaces, highlighting the ways

these interactions shape their sense of place. This study further explores

the confluence of gender and placemaking, providing a nuanced understanding

of the social, cultural, and physical factors influencing women's experiences

in such spaces. By offering strategic insights and recommendations, the

research envisages facilitating the creation and governance of public open

spaces that respect gender equality and social inclusion. |

|||

|

Received 06 September 2023 Accepted 14 November 2023 Published 07 December 2023 Corresponding Author Arushi

Malhotra, ar.arushimalhotra@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i2.2023.671 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Women, Ethnography, Public Open Spaces,

Intersectionality, Gender-Sensitive Design |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Public

open spaces which have traditionally been conceived, shaped, and defined by

male-oriented interests, have seen a dramatic transformation in their purpose

and accessibility over the years. In the 19th century, these areas, including

parks, public plazas were primarily tailored for men, a decision that cast a

societal stigma on women who frequented such spaces. In the 20th century, the

main focus of urban design was on giving priority to the automobiles, and the

developments often compromised the safety and convenience of women pedestrians

or cyclists. However, these paradigms began to change with the emergence of the

'spatial turn' and 'third wave of feminism' during the 1980s. These movements

prompted a broad, interdisciplinary feminist dialogue spanning sociology,

geography, political science, history, economics, architecture, and urban

planning & design, ushering in a fresh perspective on gender and space.

Instead of addressing 'women's issues' in a vacuum, the emphasis shifted

towards a relational understanding of gender dynamics. This progression, more

than a mere shift from 'women's studies' to 'gender studies,' heralded three

crucial conceptual changes:

1)

The recognition of a gendered division of public spaces, where

women often experience feelings of unwelcome or insecurity,

2)

The acknowledgement of gender's role in dictating access to public

spaces, often limiting women's reach compared to men, and

3)

The comprehension of how gender intersects with other social

identities—such as race, class, and sexuality—to shape an individual's

experience within public spaces.

This

evolving discourse continues to impact women's perceptions and experiences of

public open spaces. Low (2006).

2. Research Methodology AND Scope of the study

The

aim of this study is to examine the gender dynamics in public open spaces, with

a particular focus on the emirate of Dubai. The study seeks to understand how

public open spaces can be effectively designed and managed to be inclusive and

responsive to the needs and experiences of diverse individuals, considering the

intersectionality of gender, race, class, and other social categories.

To

explore the complexities of diversity in everyday life, ethnography is employed

as a valuable research tool. Living in a diverse environment presents

challenges that can shape social encounters and interactions Peterson (2017). Ethnography serves as a research

methodology to uncover the authentic and hidden narratives that shape these

social dynamics within the public sphere. By using ethnographic methods, this

study contributes to the understanding of socio-spatial relationships in public

spaces and informs urban realm theory and practice. In addition to this,

On-Site Face-to-face interviews were designed to explore the effectiveness of

existing urban design and planning practices in providing gender equality and

social in public open space.

The

study also aims to develop interventions and recommendations that promote the

design of public open spaces aligned with the principles of intersectionality.

Intersectionality acknowledges the interconnectedness of various social

identities, such as gender, and recognizes the diverse experiences and needs of

individuals within these intersecting categories. By considering

intersectionality in the design and management of public open spaces, the goal

is to create environments that are more inclusive, accessible, and equitable

for all individuals, regardless of their background, gender, or identity.

3. Gender dynamics in Public Open Spaces

3.1. Social construction of gender AND public space behavior (PSB)

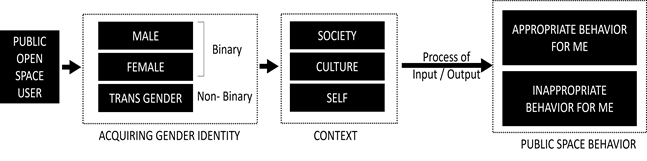

Gender,

as a socially constructed concept, greatly influences the way individuals

experience and interact with public spaces. According to Butler (1990), gender is not

a biological given but a societal creation shaped by norms, roles, and

expectations. This socially constructed understanding of gender has profound

implications for public space behavior (PSB), which

encompasses the varied ways individuals behave, interact, and perceive public

spaces Figure 1. PSB is shaped

by a myriad of socio-cultural factors, including gender. Notably, public spaces

have traditionally been designed and regulated in line with male-dominated

norms and practices. As Spain (1992). argues, public

spaces often mirror the gender biases present in wider society, and these

biases influence how individuals of different genders interact with and

perceive public spaces.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Showing Social Construction of Gender & Public

Space Behavior (PSB) Source Author Generated |

Women

influenced by socially constructed gender roles and expectations, often

navigate public spaces differently than men. Many women may feel discomfort,

exclusion, or threat in public open spaces due to gender-based harassment or

violence Loukaitou-Sideris

(2016). This fear may

manifest in women being more cautious and selective about when, where, and how

they engage with public open spaces Valentine

(1989). Meanwhile,

men, also shaped by gender norms, are generally more visible and active in

public spaces, reflecting societal expectations around masculinity and public

presence. Their PSB is often characterized by greater spatial freedom and less

fear of harassment or violence.

Individuals

who identify as non-binary or transgender face their unique set of challenges

in public spaces. They frequently encounter alienation and vulnerability due to

societal norms that typically do not recognize or accommodate their identities Doan (2010). They may

experience greater levels of discomfort, discrimination, or violence, further

complicating their interaction and navigation in public spaces.

3.2. Perception of spaces -Social and cultural factors

The

perception of spaces, particularly public open spaces, is largely influenced by

a complex interplay of social and cultural factors. How individuals interpret

and respond to these spaces is not only a reflection of their personal

experiences but also a function of the broader societal structures in which

they exist Low (2017).

Socio-cultural norms and values play a significant role in shaping an

individual's understanding and engagement with public spaces. Cultural beliefs

can influence individuals' use of space, determining what activities are deemed

appropriate in different settings Jackson (1984). Public spaces

are also often symbolic sites, imbued with social meanings that are understood

and interpreted in specific cultural contexts Mitchell (2003).

Gender,

as a social construct, has a profound impact on the perception of spaces.

Public spaces are often designed and regulated according to male-dominated

norms, potentially leading to feelings of discomfort or exclusion for women and

other genders Spain (1992). Socially

constructed gender roles and expectations also lead to differential patterns of

use and behavior in public spaces Valentine (1989).

Moreover,

other identity markers such as race, age, socio-economic status, and disability

also contribute to the perception of spaces. Racialized or marginalized groups

may perceive public spaces as exclusionary or unsafe due to systemic racism and

discrimination Low (2009). Similarly,

individuals with disabilities might find public spaces inaccessible or

challenging due to lack of proper infrastructure or accommodations Imrie (2003).

3.3. Challenges faced by Women in Public Open Spaces

Women's

experiences in public open spaces are frequently shaped by an array of complex,

interrelated challenges. These challenges often stem from a combination of

social, cultural, and physical factors, and can limit their freedom, safety,

and overall usage of public open spaces. Some of the challenges which are

directly related to the built domain can be categorized under the following

heads:

·

Safety Concerns: One of the most pervasive challenges is the

fear of harassment and violence. Women often feel unsafe in public spaces,

particularly during certain times of the day or in areas that are poorly lit or

secluded Loukaitou-Sideris

(2016). This fear can

limit their mobility and usage of public spaces.

·

Design and Planning: Public open spaces often lack design

considerations that cater to the needs of women. For example, a lack of clean,

safe, and accessible public toilets can disproportionately impact women Greed (2019). Additionally,

amenities like seating, play areas for children, or well-lit walking paths,

which could enhance women's comfort and enjoyment of public spaces, are often

inadequate or absent Whyte (1980).

·

Representation: The lack of representation in decision-making processes

pertaining to urban planning and design often results in spaces that do not

address women's needs and experiences Beall (1996). Women's

voices and perspectives are crucial in creating spaces that are truly inclusive

and accessible.

Addressing

these challenges necessitates a holistic and intersectional approach in urban

planning and design. Spaces should be designed with an understanding of the

diverse needs and experiences of women, and policies must be put in place to

ensure their safety and inclusion Loukaitou-Sideris

(2016).

4. Intersectionality, Public Open Spaces and Safety

The notion of public open spaces has

long been intertwined with the urban fabric, underpinning a city's character,

livability, and social cohesiveness. However, the interplay between

intersectionality, public open spaces, and safety brings a new layer of

complexity to the discourse. When it comes to using public open spaces the

aspect of safety plays a vital role in it. Recent studies indicate that

personal safety is an important and crucial factor of lifestyle options, and

crime is said to be one of the main problems threatening the quality of urban

life. Newport (2002). Understanding this nexus is key to shaping

inclusive and safe environments for all residents, regardless of their gender,

ethnicity, socio-economic status, or other identity markers.

4.1. Intersectional experiences in Public Open Spaces

The theory of intersectionality, a

term first coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989,

underscores the intertwining of social categorizations, such as race, class,

and gender Crenshaw (1989). It proposes that these overlapping identities can

result in compounded systems of discrimination or disadvantage. The theory

emphasizes the importance of recognizing the multidimensional and complex

nature of individuals' identities, as each facet shapes their societal

experiences Cho et al. (2013).

Public open spaces, including parks,

squares, and streets, are generally perceived as democratic spaces, offering

equal access to all Madanipour

(2013). Nonetheless, the actual experiences within these

spaces can be significantly influenced by the intersectionality of individuals'

identities. Factors such as gender, race, disability, age, and socio-economic

status, among others, can affect how people perceive and interact with these

public spaces Loukaitou-Sideris

(2016).

For instance, women may feel unsafe

or unwelcome in certain public spaces due to various reasons, including

potential harassment, lack of accessibility, or inadequate facilities that

cater to their specific needs Greed (2019). As a result, they may choose to avoid particular

spaces at specific times out of fear of harassment Valentine

(1989).

4.2. Safety as an intersectional issue

Safety, and more specifically the

perception of safety, plays a critical role in how individuals interact within

their environments. Both actual and perceived safety shape behavior, often with

the latter having a greater influence. This notion, that perceived safety can

profoundly influence behavior, holds considerable weight in understanding the

dynamics of public spaces and human interaction within them. In most of the

cases ‘actual personal safety’ and ‘perceived personal safety’ differ from each

other and it is the ‘perceived personal safety’ that greatly influences our behaviour. This drives people to avoid places that they

directly or indirectly associate with personal risk. Thus, perception of danger

in any urban public space plays a vital role in human interactions with the

environment. Keane (1998)

In their investigation of the

"fear of crime," Farrall et al. (1997) expanded on this idea by looking at the psychological

effects of perceived safety and how it influences behavior. Their results

supported the hypothesis that fear has a substantial influence on people's

decisions regarding when, where, and how to engage with their surroundings.

Fear is frequently impacted by subjective perception rather than objective

truth. Furthermore, Loukaitou-Sideris

(2016) argued that the design and layout of public spaces

can contribute to feelings of safety or danger. Features like adequate

lighting, clear sightlines, and visible security measures can enhance perceived

safety, while poorly lit or isolated areas may provoke fear.

Moreover, perceived safety in public

spaces is an intersectional issue, with various social categories like gender,

race, and class influencing an individual's perception of safety. For instance,

Day's study (1999) on "Embassies and Sanctuaries: Women's Experiences of

Race and Fear in Public Space," suggested that women of color may perceive

public spaces as more dangerous due to experiences and fears of racialized and

gender-based violence.

4.3. Crime And Vegetation

The relationship between crime and

vegetation has had some contradictory views over the years. Although vegetation

had been positively linked to fear of crime in studies conducted in the 1990’s,

recent studies hint towards the existence of a negative relationship between

the two.

There has been a long tradition of

addressing the issue of crime by removing vegetation. In 1285, the English King

Edward I forced the dwellers and property owners to clear the highway edges of

trees and shrubs in order to reduce robberies along the highway. Pluncknett (1960). The tradition continued across North

America even in 1990’s where the municipalities, park owners and park

authorities engaged in activities to remove vegetation as it was believed to

conceal and facilitate criminal acts. Michael and Hull

(1994).

Dense vegetation has generally been

linked to fear of crime. One of the important factors that comes into play in

this is the ‘view distance’. It has been observed in most of the cases that

fear of crime is higher in areas or spaces where vegetation blocks the view

completely thus acting as a potential cover for the criminals to conceal their

act and hide as well as increasing the fear of crime. Thus, large shrubs,

underbrush, dense woods, and poorly maintained green spaces diminish visibility

and in turn become capable in supporting criminal activities.

A well-maintained green area does

not block views. Widely spaced high canopy trees, flowers, low height shrubs

etc. have negligible effect on visibility and are highly unlikely to provide a

cover for criminal activities. The fact that vegetation aids criminal

activities may hold true for visibility decreasing forms of vegetation but well

maintained, widely spaced and visibility preserving forms of vegetation in no

way promote crime. In addition to this is has been observed that residents

living in ‘greener’ surroundings report lower levels of aggressive and violent behaviour, fear and fewer incivilities. This was further

backed by comparing the crime rates of different areas having varying levels of vegetation

around them. Sullivan (2001).

4.4. Prospect- Refuge Theory

The Prospect-refuge theory was proposed

by Appleton in 1975 which further elaborates on the phrase ‘to see without

being seen’, given by Lorenz in 1964, as a primitive human behaviour. The study

provides a potential framework for studies involving safety in public places

from criminal and notorious activities. It helps dwellers to perceive how safe

their environment appears to be Luymes (1995)

According to this theory, the users

rate themselves safe in any urban environment based on three parameters which

offered visibility, which are as follows:

·

Light

·

Prospect open spaces

·

Unambiguous refuse

Most of the environmental features

which are directly related to safety indicates that light is the major factor

followed by open space and unambiguous refuse.

4.2. Safety And Entry Fee

Revenue generation for maintenance

purposes is a standard reason behind charging an entry fee for public green

spaces. However, several studies have shown an intriguing connection between

safety and the imposition of these fees, particularly in how it affects usage

by women Fenster (2005). Studies indicate a tendency among women to avoid no-fee

parks, associating them with a perceived decrease in safety Greed (2019). This pattern could be linked to various factors. Parks

that impose an entry fee often provide better maintenance and superior

facilities due to the financial resources generated, leading to a more regular

presence of security personnel or staff Madanipour (2013). This increased level of management and regulation can

enhance the perception of safety Loukaitou-Sideris (2016). Furthermore, an entry fee may deter potential wrongdoers,

adding an additional layer of security Reed (2017).

Conversely, parks that do not charge

entry fees may lack sufficient maintenance and security measures due to funding

constraints. This can inadvertently create environments perceived as unsafe,

especially for individuals or groups already vulnerable due to intersectional

identities Crawford (2009).

However, it's critical to address the

possible negative impact of entry fees. These fees could potentially limit

access for individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds, contradicting the

inclusive ethos of public spaces Mitchell (2003). Thus, it's essential to consider strategies like

progressive pricing or subsidized rates for disadvantaged groups Brownlow (2006).

Thus, the relationship between safety

and entry fees in public green spaces underscores the intricate interplay of

economic factors, safety perceptions, and intersectionality. Public space

management and urban planning must carefully consider this relationship to

achieve the delicate balance between safety, accessibility, and inclusivity Low (2005).

5. Emerging parameters which influence creating successful public open spaces from women’s perspective

Understanding

public open spaces from a woman's perspective demands recognition of the gendered

nature of space and the unique challenges faced by women (discussed under

section 3 & 3.3 of this paper). In order to create inclusive, accessible,

and safe urban environments, some of the emerging parameters and factors that

can guide the design and planning of successful public open spaces that cater

to women's needs and experiences from the literature study (section 3 & 4

of this paper), are as follows:

·

Accessibility: This involves ease of entry and exit, as well as the

ability to reach or leave the space via multiple modes of transportation.

Public open spaces should be reachable by foot, bike, public transportation or

car, and pathways should be wheelchair accessible.

·

Barriers and Entrances: These should be designed with security in mind, allowing a

flow of people while also preventing unauthorized access. Barriers may also be

used to separate different sections of the space, while entrances should be

clearly marked and easily identifiable.

·

Territoriality: This refers to the use of physical design to encourage

people to feel a sense of ownership over public spaces, which can enhance

safety by discouraging misuse and promoting stewardship. Elements may include

unique design features or art that reflect the local community.

·

Interpersonal Distance: Public spaces should provide enough space for individuals

to maintain comfortable distances from others, enhancing feelings of personal

security and comfort.

·

Inclusivity: Spaces should cater to women of different ages, abilities,

and cultural backgrounds. This could mean providing elements such as

breastfeeding spaces, wheelchair accessible routes, and culturally sensitive

design.

·

Lighting: Adequate, well-designed lighting enhances visibility,

making spaces safer and more welcoming after dark. It can also contribute to

the overall aesthetic appeal of the space.

·

Walkability: This involves having well-maintained sidewalks, pathways

and crosswalks that are safe for pedestrians. They should be separated from

traffic, well lit, and wide enough to accommodate both slower and faster

walkers.

·

Landscaping/Green Spaces: Including green elements like trees, gardens, or lawns not

only enhances aesthetic appeal, but also contributes to overall well-being by

providing spaces for relaxation, reducing urban heat, and improving air

quality.

·

Restrooms: Public restrooms should be clean, safe, and accessible.

They should also include amenities like changing rooms and other

gender-specific facilities. Consideration should be given to the location and

visibility of restrooms to enhance user safety.

·

Drinking Water, Food and

beverages: Availability of clean drinking water

fountains and options for food, beverages and other refreshments is crucial,

both for basic needs and to encourage longer stays in the public space.

·

Security Personnel: The presence of trained security staff can greatly enhance

feelings of safety, by providing immediate help in case of danger or problems.

They should be visible, accessible, and approachable.

·

CCTV: Surveillance systems can deter potential crime and provide

users with a sense of safety, especially in secluded or less busy areas of the

space.

·

Visual Connections: Spaces should be designed to ensure clear sightlines and

open views, allowing users to see what is happening around them, which can

greatly enhance feelings of safety and security.

·

Exercise/Relaxation: Public spaces should provide facilities for both exercise

(like bike paths, exercise equipment or yoga spaces) and relaxation (like

benches, lawns or shaded areas). This caters to different needs and encourages

longer use of the space.

·

Seating: Benches and seating areas should be placed strategically

to allow users a sense of privacy and control. This could mean positioning

benches away from busy streets, reducing noise levels, or providing comfortable

and shaded seating clusters for social interaction.

A detailed coding matrix was developed to understand the

relationships between the emerging parameters and factors that influence in

creating successful POS with the identified challenges faced by Women in POS.

This further helps in developing relevant proposals/strategies for the study. .

Table 1

|

Table 1 Matrix Showing Cross

Mapping of the Emerging Parameters / Factors Influencing Creating Successful

POS with the Identified Challenges Faced by Women in POS |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Matrix showing cross mapping of the emerging parameters / factors

which influence creating successful POS with the identified challenges faced

by Women in POS |

Emerging Parameters / Factors for creating ‘successful’ POS |

||||||||||||||||

|

Accessibility |

Barriers

and Entrances |

Territoriality |

Interpersonal

Distance |

Inclusivity |

Lighting |

Walkability |

Restrooms |

Landscaping |

Drinking

Water |

Food

& beverages |

Security

Personnel |

CCTV |

Visual

Connections |

Exercise/Relaxation |

Seating |

||

|

Identified challenges |

Safety |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Design |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Representation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Author Generated. |

|||||||||||||||||

6. Case studies AND data collection

Four different case studies were chosen to examine the necessity and effects of implementing various strategies/ approaches in the existing (and prospective) public open spaces in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, while evaluating the current public promenade.

In the context of the research investigating the social construction of gender and behavior in public spaces, our analytical model aims to:

· Explore how diverse design strategies incorporated in public spaces can contribute to the successful design and planning of public promenades in multicultural cities such as Dubai, UAE. This analysis is performed with a specific focus on how these spaces cater to women's needs and experiences, underlining the influence of gender as a social construct on behavior in these spaces.

· Identify any potential inadequacies or challenges in the current approach to the design and development of public spaces. This aims to shed light on issues requiring further discussion to better align the design of public open spaces with the distinct needs and experiences of women, with the goal of creating more inclusive and engaging environments.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Matrix Showing Cross Mapping of

The Emerging Parameters / Factors Influencing Creating Successful POS with

the Identified Challenges Faced by Women in POS |

||||

|

Case Studies |

Remraam

Community Park |

Al Khazan Park |

Dubai Marina Walk |

Dubai Mall Fountain Promenade |

|

Selection Criteria |

||||

|

POS

Hierarchy |

Neighborhood level |

Neighborhood level |

City

Level |

City

Level |

|

Surrounding

land use (Dominant land use) |

Residential

Community |

Residential |

Mixed

land-use |

Commercial |

|

Developed

By |

Dubai

Properties |

Dubai Municipality |

Emaar

Group |

Emaar

Group |

|

Ownership |

Private |

Government |

Private |

Private |

|

User

group (Dominant) |

Middle

and high-income group |

Low and

middle-income group |

High

Income group |

Middle

and high-income group |

|

Case

study details |

||||

|

About |

Remraam is a residential community in Jumeirah

Village Circle, Dubai. It is home to over 10,000 people and is known for its

lush green spaces, including the Remraam Community

Park. The park is a popular spot for families and children, and it is also

used for a variety of community events. |

Al

Khazan Park is a zero-energy park located in the Al Safa neighbourhood

(having around 15,672 people living in the neighbourhood) of Dubai. It was

rebuilt as part of Dubai Municipality's Green Dubai initiative. The park is

now powered entirely by solar energy, making it the first of its kind in the

emirate. Al Khazan Park is a popular spot for families and children, and it

is also used for a variety of community events. There is also a water tank

that is a popular landmark for all the visitors. |

Dubai

Marina Walk is a seven-kilometre (4.3-mile) palm tree-lined waterfront

walkway in Dubai. It is a popular spot for walking, jogging, cycling, and

rollerblading. The walkway also offers stunning views of the Dubai Marina

skyline and the Arabian Gulf. The Dubai Marina Walk is home to several

restaurants, cafes, and shops. There are also several public art

installations along the walkway, including the Cobblestone Boulevard, a

pedestrianized area with cobblestone paving and street furniture. |

The

Dubai Mall Fountain Promenade is a waterfront promenade located in front of

the Dubai Mall in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The promenade is home to the

world-famous Dubai Fountain, which is a choreographed fountain show that

takes place every 30 minutes from 6pm to 11pm. The space is a popular spot

for tourists and locals alike. It is a great place to people-watch, enjoy the

views of the Burj Khalifa, and take in the spectacle of the Dubai Fountain

show. The promenade is also home to several restaurants, cafes, and shops. |

|

Size |

100,000

square meters |

1.4

hectares |

7

kilometres (4.3 miles) |

1.5

kilometres (0.93 miles) |

|

Amenities |

Playground,

jogging track, basketball court, swimming pool, communal garden |

Playground,

jogging track, basketball court, picnic area, library, water tank |

Restaurants,

cafes, shops, public art installations |

Restaurants,

cafes, shops, Dubai Fountain |

|

Estimated

number of users per day |

1,000

(Approx 65% users are women) |

1,000

(Approx 50% users are women) |

100,000

(Approx 55% users are women) |

100,000

(Approx 60% users are women) |

|

Hours |

Open 24

hours a day, 7 days a week |

Open 24

hours a day, 7 days a week |

Open 24

hours a day, 7 days a week |

Open 24

hours a day, 7 days a week |

|

Year of

construction |

Phase-1

2013 |

Initial

Construction-1980’s; Reconstructed in 2019 |

2004

(Opened for visitors in 2005) |

2008 |

|

Site

Picture |

|

|

|

|

|

Source table:

Author generated, Source Pictures: Author’s Own |

||||

A detailed coding matrix was developed for the study which helped in understanding the relationships between different parameters and factors that can guide the design and planning of successful public open spaces that cater to women's needs and experiences at the identified case study areas. After data collection (using observation and ethnographic tools and techniques) the coding matrix is then used for extracting inferences which helped formed the basis of discussion and development of various strategies.

|

Table 3: Coding Matrix Showing Availability of the Identified

Parameters / Factors at the Selected Case Study Sites for the Research. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Coding Matrix showing availability of

the identified parameters / factors |

Emerging Parameters / Factors for

Creating ‘Successful’ POS |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Accessibility |

Barriers and Entrances |

Territoriality |

Interpersonal Distance |

Inclusivity |

Lighting |

Walkability |

Restrooms |

Landscaping |

Drinking Water |

Food & beverages |

Security Personnel |

CCTV |

Visual Connections |

Exercise/Relaxation |

Shaded Seating |

|||

|

Identified Case studies |

Neighbourhood level |

Case Study 1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Case Study 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||

|

City Level |

Case Study 3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Case Study 4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Source: Author Generated |

||||||||||||||||||

7. Discussion

The research conducted a comprehensive analysis of gender dynamics in public open spaces, focusing on the social construction of gender, the influence of social and cultural factors on the perception of spaces, challenges faced by women, intersectionality and safety, and emerging parameters for successful public open spaces from a women's perspective. Additionally, case studies were conducted in Dubai, UAE, to evaluate the design and planning of public spaces.

The findings reveal that gender is a socially constructed concept shaped by norms, roles, and expectations, which significantly impact public space behavior. Traditional male-dominated norms often shape the design and regulation of public spaces, leading to different experiences for individuals based on their gender. Women, influenced by socially constructed gender roles, navigate public spaces differently than men, facing discomfort, exclusion, or threats due to gender-based harassment or violence. On the other hand, men enjoy greater spatial freedom and experience less fear due to societal expectations of masculinity.

The perception of public spaces is influenced by a complex interplay of social and cultural factors, including cultural beliefs, socio-economic status, race, and disability. Public spaces often reflect gender biases and other forms of discrimination, affecting how individuals perceive and interact with these spaces. Women encounter various challenges in public open spaces, such as safety concerns, inadequate design and planning, and a lack of representation in decision-making processes. These challenges limit their mobility and usage of public spaces and hinder their comfort and enjoyment.

Addressing these challenges requires a holistic and intersectional approach in urban planning and design, taking into account the diverse needs and experiences of women. Safety, both actual and perceived, plays a crucial role in shaping behavior within public spaces. Design elements such as lighting, visibility, and security measures are essential for enhancing feelings of safety and reducing fear. Contrary to popular belief, well-maintained green areas with preserved visibility and widely spaced trees contribute to a sense of safety and have been associated with lower levels of aggressive behavior and fear.

To create successful public open spaces from a woman's perspective, several emerging parameters and factors need to be considered. These include accessibility, design of barriers and entrances, territoriality, inclusivity, lighting, walkability, landscaping/green spaces, provision of restrooms, availability of drinking water and food, presence of security personnel and CCTV, visual connections, and the availability of facilities for exercise and relaxation. These elements enhance safety, comfort, and inclusivity for women, catering to their diverse needs and experiences. The research conducted case studies in Dubai, UAE, to evaluate the implementation of different design strategies and approaches in public open spaces. The aim was to explore how these spaces cater to women's needs and experiences and identify potential areas for improvement. Data collection involved observation and ethnographic tools, which were analyzed using a coding matrix to extract valuable inferences. These findings serve as a foundation for developing strategies that promote inclusive, accessible, and safe public spaces for women and guide future urban development projects.

8. Analysis AND Proposed interventions

Based on the literature review and inferences from the case studies, the following practices can be kept in mind while designing public open spaces that cater to women's needs and experiences. Although there is no single blueprint for developing an inclusive, accessible, and safe urban environment, however, ‘successful’ spaces do seem to share some common aspects/ elements. These practices can be broadly categories under two heads: Design and Management for ease of implementation.

8.1. Development Strategies for Design

· Incorporate Adequate Lighting: Ensure that future developments prioritize well-designed and ample lighting systems to enhance visibility and promote a sense of safety within public spaces, especially during evening hours.

· Implement Visible Security Measures: Integrate visible security measures, such as strategically placed surveillance cameras or the presence of security personnel, to deter potential criminal activities and enhance perceptions of safety.

· Optimize Sightlines: Design public spaces with clear sightlines and open views to minimize potential hiding spots and increase visibility, contributing to a greater sense of safety and security.

· Ensure Universal Accessibility: Embrace universal design principles in future development projects to ensure that public spaces are accessible and inclusive, catering to individuals of all ages, abilities, and mobilities.

· Promote Active Transportation Infrastructure: Prioritize the integration of infrastructure that supports active modes of transportation, such as pedestrian walkways and cycling lanes, to encourage sustainable transportation options and enhance accessibility.

· Foster Community Gathering Spaces: Allocate designated areas within public spaces for community gathering and social interaction, incorporating seating clusters, communal areas, or gardens to cultivate a sense of community engagement and cohesion.

· Embrace Art and Cultural Integration: Integrate public art installations, cultural symbols, and storytelling elements that celebrate diversity and promote inclusivity, contributing to a vibrant and culturally rich public space environment.

· Champion Ecological Sustainability: Emphasize ecological sustainability in future developments by incorporating elements such as rain gardens, sustainable drainage systems, and the use of native plant species, fostering environmentally friendly and resilient public spaces.

8.2. Proposed Guidelines for Management

· Facilitate Participatory Design Processes: Encourage participatory design processes involving the local community to ensure their voices and perspectives are actively considered in the planning and development of public spaces, promoting a sense of ownership and fostering inclusive outcomes.

· Emphasize Cultural Sensitivity: Ensure that design elements respect and reflect the cultural backgrounds and heritage of the local community, promoting inclusivity and a sense of representation within public spaces.

· Provide Gender-Specific Facilities: Prioritize the provision of gender-specific facilities, such as clean and safe public restrooms, breastfeeding spaces, or changing rooms, to cater to the specific needs of different genders within public spaces, fostering inclusivity and accessibility.

· Curate Diverse Programming: Encourage the organization of community programs, events, and activities that celebrate diversity and engage individuals from different backgrounds, promoting social interaction, inclusivity, and community cohesion.

· Establish Effective Maintenance and Upkeep: Implement robust maintenance and management strategies to ensure the cleanliness, safety, and functionality of public spaces over time, creating inviting and well-maintained environments for all users.

· Implement Safety Policies and Procedures: Develop and enforce comprehensive safety policies and procedures to address potential safety concerns within public spaces, including emergency response protocols and risk management strategies, prioritizing the well-being of users.

· Foster Community Engagement and Education: Actively promote community engagement and education initiatives to raise awareness about safety, inclusivity, and responsible use of public spaces, fostering a sense of ownership and shared responsibility among the community.

These development strategies and proposed guidelines serve as a foundation for future urban development projects, aiming to create inclusive, accessible, and safe public spaces that cater to the diverse needs and experiences of individuals within the community especially women users.

9. Conclusion

The research emphasizes the importance of adopting an intersectional approach in urban planning and design to create more inclusive, accessible, and safe public open spaces. By recognizing the diverse experiences and challenges faced by women and other marginalized genders, urban planners and designers can address gender biases, ensure representation, and incorporate design elements that promote safety, comfort, and engagement for all individuals. The findings from the case studies in Dubai provide insights into the effectiveness of various design strategies and highlight the need for ongoing discussions and improvements in creating gender-responsive public spaces.

The research contributes to the broader discourse on gender and public space, shedding light on the complex dynamics at play and providing practical recommendations for designing inclusive and engaging environments. By considering the social construction of gender, intersectionality, and the diverse needs and experiences of individuals, urban planners and designers can foster a sense of belonging, empowerment, and well-being in public open spaces for everyone.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Beall, J. (1996). Urban Governance: Why Gender Matters. Gender in Development Monograph Series, UNDP.

Brownlow, A. (2006). An Archaeology of Fear and Environmental Change in Philadelphia. Geoforum, 37(2), 227-245.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785-810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

Crawford, A. (2009). Criminalizing Sociability through Anti-social Behaviour Legislation: Dispersal Powers, Young People and the Police. Youth Justice, 9(1), 5-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225408101429

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 140, 139-167.

Day, K. (1999). "Embassies and Sanctuaries: Women's Experiences of Race and Fear in Public Space." Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 17(3), 307-328. https://doi.org/10.1068/d170307

Doan, P. (2010). The Tyranny of Gendered Spaces - Reflections from Beyond the Gender Dichotomy. Gender, Place & Culture, 17(5), 635-654. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.503121

Farrall, S., Bannister, J., Ditton, J., and Gilchrist, E. (1997). "Questioning the Measurement of the 'Fear of Crime': Findings from a Major Methodological Study." British Journal of Criminology, 37(4), 658-679. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014203

Fenster, T. (2005). The Right to the Gendered City: Different Formations of Belonging in Everyday Life. Journal of Gender Studies, 14(3), 217-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230500264109

Fincher, R., and Iveson, K. (2008). Planning and Diversity in the City: Redistribution, Recognition and Encounter. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-06960-3

Greed, C. (2019). Inclusive Urban Design: Public Toilets. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351200912-8

Imrie, R. (2003). Architects' Conceptions of the Human Body. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21(1), 47-65. https://doi.org/10.1068/d271t

Jackson, J. B. (1984). Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. Yale University Press.

Keane, C. (1998). "Evaluating the Influence of Fear of Crime as an Environmental Mobility Restrictor on Women's Routine Activities." Environment and Behavior, 30(1), 60-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916598301003

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (2016). "Fear and Safety in Transit Environments from the Women's Perspective." Security Journal, 29(1), 242-256. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.9

Low, S. (2005). Theorizing the City: The New Urban Anthropology Reader. Rutgers University Press.

Low, S. (2017). Social Sustainability: People, Place, Culture. Journal of Urban Design, 22(2), 166-187.

Low, M., (2006). The Social Construct of Space and Gender. European Journal of Women's Studies, 13(2), 119-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506806062751

Madanipour, A. (2013). Public and Private Spaces of the City. Routledge.

Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. Guilford Press.

Phadke, S., Khan, S., & Ranade, S. (2011). Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. Penguin Books.

Reed, A. (2017). Security and the Politics of Resilience: An Aesthetic Response. Routledge.

Spain, D. (1992). Gendered Spaces. University of North Carolina Press.

Valentine, G. (1989). The Geography of Women's Fear. Area, 21(4), 385-390.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.