ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Generated Visualizations of Musical Patterns

Pravat Kumar Routray 1![]()

![]() ,

Manish Nagpal 2

,

Manish Nagpal 2![]()

![]() , Megha Gupta 3

, Megha Gupta 3![]()

![]() ,

Amanveer Singh 4

,

Amanveer Singh 4![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India,

2 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan 174103, India

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh,

India,

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The paper will

discuss the new area of AI-composed visualizations of musical patterns, which

is a convergence of music theory, computational creativity, and visual arts.

It explores how such audio formats as pitch, rhythm, harmony, and timbre can

be produced using artificial intelligence via visual media in a dynamic and

aesthetically coherent format. The research places this change in the context

of interdisciplinary concepts, taking into account the aspects of perceptual,

cognitive, and ethical. The system recapitulates the objective and the

affective aspects of music by using neural networks that have been trained on

multimodal data and relates them to the visual parameter of color, geometry

and motion. The proposed system architecture combines the steps of the audio

feature extraction, representation learning, and visual synthesis. As a

result of experimental production and qualitative analysis, a number of

recurring motifs and emergent visual structures are found, which represent

associations between tonal density and color complexity, regularity in

rhythm, and geometric symmetry, and harmonic consonance and spatial fluidity.

The findings illustrate the interpretive depth of the AI-mediated sound-image

translations to illustrate how artificial intelligence can generate work of

art that can trigger aesthetic responses in the human condition.

Nevertheless, the paper also notes that there are a number of limitations:

the visualization in real-time is technically limited; the assessment of

aesthetics is subjective by nature; and the biases of data in training

corpora are potentially a problem concerning the reproducibility and the

fairness. |

|||

|

Received 01 February 2025 Accepted 23 April 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Pravat

Kumar Routray, pravatroutray@soa.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6697 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Generated

Art, Music Visualization, Multimodal Learning, Computational Creativity,

Aesthetic Cognition |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The history of human creativity is a turning point due to the combination of artificial intelligence, music, and visual arts. Along with the increasing abilities of computational systems to read and write more and more complex patterns, they challenge us to rethink the limits between sound and sight, the field of analysis and the field of aesthetics. One of the most exciting points of cross-disciplinary intersection between these fields is AI-generated visualization of musical patterns, which is also one of the attempts to represent music visually, yet disclose its underlying structures, emotional processes, and cultural implications through the application of algorithms. Music on its part is a temporal art. It is a time-based process in which weaving rhythms, pitch and timbre together create patterns that appeal to the intellect and the heart. Visual art on the other hand is space; it captures a moment, structure and relationship in a non-moving or a moving frame. The point of intersection between these time and space spaces is the challenge and the opportunity. But how can the forms of melody and harmony be translated in color and line in action? So what can a crescando physically appear like or what can a dissonance physically look like? These questions are no longer a poetic one, even with the introduction of machine learning, especially deep neural networks with multimodal comprehension, which can be computed Ji et al. (2020). Musical visualization is an area that has been a long time subject of study by artists as well as scientists. The visualizers used at the beginning of the analogue period, including the color organs of the 18th century or the oscilloscope-like light displays of the 20th, were dependent on mechanical or electronic converting frequencies to light. Nevertheless, the systems were highly deterministic and not that semantic. With the introduction of AI-based models, especially models that are trained on huge datasets of paired audio and visual media, it has been possible to approach it in a more subtle way. The use of AI systems today can deduce and create visual representations that capture both the acoustic and emotive meaning of music pieces, and thus can produce visual representations that are interpretive and not reactive Ma et al. (2024). This intersection builds upon various fields: to the theory of music, which provides a formal description of the structure of pitches and their harmonic relationship; to data science, which provides the computational means of the analysis and modelling of high-dimensional data; to visual arts and the psychology of perception, which base the translation process on the principles of aesthetics and cognitive psychology. It is an attempt not just to plot sound against image but also to examine the question of how meaning and emotion can cross over sensoritious barriers, which also resonates with the synesthetic experiences, where the sensory medium evokes the other. Besides, the application of AI in this regard raises deep philosophical and ethical issues Briot and Pachet (2020). Who or what is the author when an algorithm creates an aesthetical work of visualization of a symphony or a jazz improvisation? Is the machine only a tool of extension of human imagination, or is it a creative agent itself? These types of questions place the technical exploration in context in terms of the larger discourses of computational aesthetics, creativity and authorship.

2. Related Work

The visualization of music is a long and complex history that has developed as an experimentation with art and a computational analysis. The ancient history of visual representations of sound can be traced back to the 18th century, when the color organs (mechanical machines where the lights in different colors were shown as a reply to the musical sounds) were invented. These initial experiments though mostly aesthetic in nature formed the basis of the synesthetic correspondence between sound and color. Visual music in the 20th century Visual music was introduced by such pioneers as Oskar Fischinger, Norman McLaren and John Whitney, who created abstract animations and were timed to musical pieces, adding motion and form as visual equivalents to rhythm and melody Ji et al. (2023). Their work laid down some aesthetics principles to map auditory and visual aspects which are still applied in the computational art. Algorithms and data-driven solutions started to take over the discipline with the emergence of the digital technology. In early computer-generated visualizations like Winamp visualizers and MIDI-based animation, signal processing methods were used to encode amplitude, frequency, and tempo values into a geometric pattern. These systems had drawbacks in their inability to be interpreted and the fact that they were restricted to rule-based mappings despite being visually engaging. The recent progress in the field of artificial intelligence and machine learning, especially deep neural networks and generative models, have transformed this field into revolution Hernandez-Olivan and Beltran (2021). DeepDream, GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) and diffusion models, among others have allowed AI to sample the intricate interconnections between sonic characteristics and visual imagery that create images that capture the structural and emotional complexity of music. The concept of a cross-modal correspondence with the use of AI has been studied on multiple occasions, drawing parallels between auditory characteristics and visual textures or colors by employing multimodal embeddings. Google Magenta, OpenAI Jukebox, and Deep Visualization systems are among the projects that have helped in gaining an insight on how AI can interpret and recreate musical information Herremans et al. (2017). Neighboring to this, however, a lot of the current work is based upon aesthetic novelty, or technical feasibility, but considers little or none in the way of cognitive interpretation and ethical concerns. This paper aims to fill this gap, putting AI-generated musical visualizations in a wider interdisciplinary and philosophical framework.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work on

AI-Generated Musical Visualizations |

||||

|

Approach |

Techniques

Used |

Audio

Features Mapped |

Visual

Parameters Used |

Key

Findings |

|

Mechanical

light projection |

Optical-mechanical

mapping |

Pitch,

loudness |

Color,

brightness |

First

attempt at visualizing sound through light |

|

Animated

film synchronization |

Frame-by-frame

abstraction |

Rhythm,

tone |

Motion,

geometry |

Pioneered

abstract visual music |

|

Analog

computer synthesis Zhu et al. (2023) |

Oscilloscope

and rotation algorithms |

Frequency,

amplitude |

Line

motion, rotation |

Early

computational visual music |

|

Real-time

DSP visualizer |

FFT

and waveform analysis |

Amplitude,

tempo |

Color

waveforms |

Popularized

digital visualization |

|

Interactive

computational art Wen and Ting (2023) |

Parametric

mapping |

Rhythm,

timbre |

Color,

form |

Introduced

interactive sound-image mapping |

|

MIDI-driven

animation |

MIDI

note mapping |

Pitch,

duration |

Shape,

velocity |

Automated

visual rhythm generation |

|

Algorithmic

visualization |

Temporal

mapping |

Pitch,

duration |

Scrolling

bars, color |

Clear

music structure visualization |

|

Deep

learning framework Von Rütte et al. (2022) |

RNNs,

CNNs |

Melody,

harmony |

Color,

texture |

Learned

cross-modal correspondences |

|

Generative

Adversarial Networks Lu et al. (2023) |

GANs,

latent mapping |

Pitch,

rhythm |

Color,

geometry |

High-quality

AI visual art |

|

Multimodal

AI |

Embedding-based

learning |

Timbre,

harmony |

Motion,

color |

Linked

visual patterns to emotion |

|

Audio-to-image

translation |

VQ-VAE,

transformers |

Spectrograms,

tempo |

Color,

geometry |

Learned

stylistic coherence |

|

Generative

diffusion AI |

Latent

diffusion models |

Spectrum,

dynamics |

Texture,

form |

High

fidelity and aesthetic control |

|

Multimodal

Transformer Pipeline Wu et al. (2020) |

Audio

embedding + GAN |

Pitch,

rhythm, timbre, harmony |

Color,

motion, geometry |

Achieves

coherent, emotionally resonant visuals |

3. Interdisciplinary Foundations

3.1. INTERSECTION OF MUSIC THEORY, DATA SCIENCE, AND VISUAL ARTS

The combination of music theory, data science, and visual arts is the conceptual and technical basis of the AI-generated visualization of musical patterns. The theory of music presents the structural and harmonic context that is required to comprehend the interaction of musical elements the pitch, rhythm, timbre, and dynamics to create meaning and emotion. These theoretical concepts lead the process of mapping of auditory features into the visually coherent representations. As an example, tonal hierarchies can be mapped in spatial hierarchies and rhythmic intensity can be mapped in motion dynamics or visual repetition Guo et al. (2021). On its part, data science provides the computational procedures that may be needed to extract, model, and interpret these musical characteristics. The data scientists can measure the elements (spectral centroid, tempo, or harmonic complexity) using the machine learning and signal processing methods, which can subsequently be used as inputs to visual encoding algorithms. Convolutional and recurrent neural networks are deep learning models, which can translate time-based musical data into a spatially rich visual representation Yu et al. (2023). The aesthetic and design structures that create not just structurally correct but also intimately affecting imagery are provided by the visual arts.

3.2. ROLE OF PERCEPTION AND COGNITION IN INTERPRETING SOUND-TO-IMAGE TRANSLATION

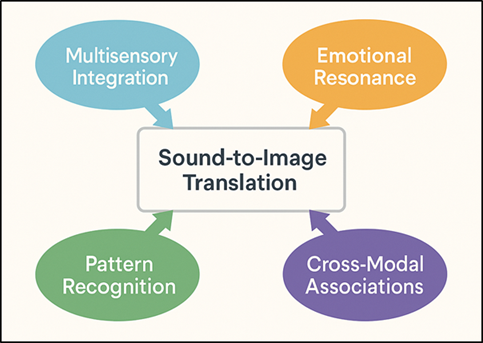

Both the human mind and human perception are very important in how to interpret translations between sound and image that are created by AI. Three processes are involved in the experience of a musical visualization; it is a complicated process of visual perception that involves multisensory integration, emotional response, and pattern recognition. According to cognitive psychology, human beings tend to find coherence within the sensual fields of experience, i.e. associating sound signals with the visual equivalents like brightness, color and motion. To illustrate, the tones of high pitch are commonly described as being lighter or brighter, whereas the tones with a low frequency can be associated with darker colours or heavier forms Zhang et al. (2023).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Cognitive and Perceptual Framework for Sound-to-Image Translation |

Such relationships can be reproduced by AI systems trained on data related to human perceptions, and this can be done by matching computational mappings with the intuitive sense. Figure 1 demonstrates how the auditory perception and visual interpretation are interconnected through cognition. The neuroaesthetic mechanism by which the brain combines auditory and visual stimuli and develops a synesthetic perception of sound involves the cross-modal processing areas of the brain, including superior temporal sulcus and occipital cortex, to combine these streams Touvron et al. (2023). In the case where AI models replicate this translation, the models replicate certain human cognition processes of abstraction and metaphor.

3.3. ETHICAL AND

AESTHETIC DIMENSIONS OF AI-CREATED ART

The creation of AI-generated art poses some of the most serious ethical and aesthetic challenges to the concepts of authorship and originality, as well as creative agency. The delineations between human and machine creativity will be blurred when an algorithm creates the visualizations of musical patterns. Is the AI just an extension of the imagination of the artist, or is an independent creator? This conflict confronts the conventional concept of artistry, originality, and property. The intellectual property presents ethical issues as well intellectual property, especially when AI models are trained with copyrighted or culturally exclusive music information without their explicit approval or recognition Yuan et al. (2024). Aesthetics AIs can be seen aesthetically as both intriguing and doubtful to the eyes. Although these works may be characterized by an impressive state of coherence and beauty, critics doubt that algorithmic aesthetics can create disinterestedness or feelings. This argument continues in the philosophy of art: in the case, beauty is a result of computation, does it still possess expressive authenticity? Moreover, the black box problem or the opaqueness of AI models makes interpretability more challenging, it is hard to place an artistic intent or comprehend the creativity logic behind generated results Liang et al. (2024).

4. System Architecture and Design

4.1. OVERVIEW OF THE AI PIPELINE FOR MUSIC-TO-VISUAL TRANSFORMATION

The design of an AI-based music-to-visual transformation system is based on the hierarchy of different computational and creative modules that altogether process auditory data into meaningful and expressive visual encodings. The pipeline is fundamentally based on three steps, namely audio preprocessing and feature extraction, feature learning and mapping, and visual synthesis and rendering. The initial step involves the transformation of digital signal processing (DSP) and feature extraction through machine learning of digital signal processing is split into quantifiable components, including pitch, rhythm, and timbre, of an instrumental, vocal, or mixed audio signal Deng et al. (2024). Such characteristics constitute the numerical basis of the translation process. The second step involves the application of deep learning based on multimodal neural networks (or variational autoencoders (VAEs) that are trained to learn a correlation between audio and visual modalities. Being able to visualize the latent features of music extracted and overlayed onto the visual features of color gradients, geometric movement, or compositional structure shared, these models visualize the extracted musical features onto the latent space (learned shared).

4.2. AUDIO FEATURE EXTRACTION (PITCH, RHYTHM, HARMONY, TIMBRE)

The successful extraction of audio features is the foundation of the transformation of music to the visual. The system comprises the objective structure as well as the expressive quality of musical compositions by breaking the sound down into measurable components. Frequency domain transformations like Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) or Constant-Q Transform (CQT) are used to analyse pitch and enable the system to determine which tones, melodic contours and harmonic intervals are dominant. Such frequencies tend to be associated with the brightness or elevation in the produced visuals, which offers a impression of tonal upliftment or downfall. Rhythm is obtained due to the analysis of the temporal domain based on onset detection, beat tracking and tempo estimation. Patterns of pulse and syncopation are mapped to visual movement or repetition, faster rhythms can be used to create the rapid geometric oscillations, and slower tempos can create the smooth and flowing transitions. Harmony which is a representation of the association of parallel pitches is picked out by chord recognition and spectral analysis. Consonant harmonies can be either translated into soft gradients or symmetrical shapes and dissonance can be translated into opposing forms or jagged edges. Timbre or tone color is a sum total of sound texture.

4.3. VISUAL ENCODING STRATEGIES (COLOR, MOTION, GEOMETRY)

The process of converting musical features extracted into visual attributes, including color, motion and geometry, is known as visual encoding. These tactics are guided by the principles of both the perceptual correlations and aesthetic design, so that the visuals both make cognitive and emotional resonance with the music they depict. Color coding is based on traditional synesthetic associations of color and sound. Bright colors (e.g., blue, white) and cool colors (e.g., red, orange) are usually associated with high frequencies, whereas warm colors (e.g., red, orange) are related to low frequencies. The changes in loudness can change the saturation or the luminance so that the pictures become vibrating or radiant with the strength of the music. These mappings can be optimized by the AI systems using reinforcement learning, to make the interaction between the audio and visual realms perceptually harmonious. Rhythm, tempo and dynamics are coded into kinetic visual representations by motion encoding. The intensity of beats can regulate the degree of movement, as rhythmic regularity can regulate the patterns of motion oscillation, rotation or expansion. The lush passages of legato may produce smooth movement and the staccato rhythms may create jagged movement. The space organization of shapes and structures are subject to geometric encoding.

5. Findings and Interpretation

5.1. TYPES OF VISUAL MOTIFS AND EMERGENT STRUCTURES OBSERVED

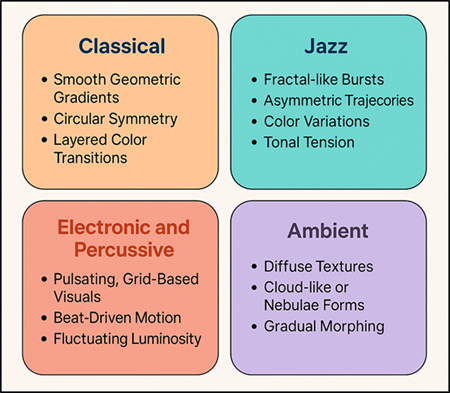

The AI-based visualizations showed a wide range of motifs and emergent forms and differed by the genre of the musical input, the tonal level, and the density of rhythms. In various experiments, different visual signatures were found in various musical forms. Classical compositions, with their harmonic regularity and gradual transition to different modes, were more likely to result in smooth geometric gradients, circular symmetry, and stratified color changes in the style of organic flow. On the contrary, jazz improvisations were creating fractal-like bursts, asymmetric paths, and color changes which were the manifestation of tonal tension and rhythmic spontaneity. Figure 2 presents visual patterns that are genre-specific as a result of AI-generated music. The electronic and percussion sounds created grid and grid based visual images with movement and brightness changing directly with the intensity of the beat.

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Genre-Based Visual Motifs in AI-Generated Musical Visualizations |

Full of sustained harmonics, ambient soundscapes produced diffuse textures that could be likened to either clouds or nebulae, and focused on gradual morphing over discrete transitions. Interestingly, too, AI systems had also been shown to possess emergent visual coherence, with complex musical inputs then leading to self-organizing visual behaviors, e.g. rhythmic clustering or harmonic wave interference, without being explicitly programmed to do so. These new tropes emphasize the fact that the AI is capable not only of learning the statistical associations but the aesthetic rules based on the training data.

5.2. CORRELATION BETWEEN MUSICAL ATTRIBUTES AND GENERATED VISUALS

The correlation between the visual representation of musical qualities and their musical characteristics was found to have apparent and explainable correlations in the analysis of AI-generated outputs. These relations were also stable over various models, which indicates that the mappings underneath the relations were not only meaningful to the perceptions but also computationally sound. Pitch showed significant association with vertical spatial location and hue of colour-frequencies of the upper pitch tended to be associated with lighter or cooler colour which was towards the upper visual field, and the lower frequencies were associated with warmer colour which was placed towards the bottom. Rhythm had an effect on the time dynamics where the tempo was used to regulate the velocity of motion and beat accents to establish pulsing or flashing patterns. Complex rhythmic syncopations produced erratic and staccato movements and steady meters produced a smooth oscillatory movement. The level of visual symmetry and density of space were determined by harmony. Chords in consonance tended to give rise to symmetrical, ordered, compositions, whereas chords of dissonance caused disorder or streeted out space distortions. Timbre meanwhile exerted a great influence on surface quality and texture, in that the metallic timbres were precise, reflective of the eye, whereas acoustic instruments were less pronounced and more smoky overtones. These correlations confirm the property of the system to encode and decode any cross-modal associations, which can be translated into auditory properties into what can be visually resonant.

5.3. ANALYSIS OF AESTHETIC COHERENCE AND INTERPRETIVE

RICHNESS

The quantitative and qualitative methods were necessary in order to evaluate aesthetic consistency and the richness of interpretations. Compositional balance and visual stability were measured using objective measures, i.e. color harmony indices, motion entropy and spatial symmetry. Qualitatively, the outputs have been checked by expert reviewers in music, art, and design in terms of resonance evoked in the audience, depth of interpretation and innovation in the art. The results were that the level of aesthetic coherence between auditory input and visual output was high. Changes in tone, tempo and dynamic range were echoed by parallel visual changes, giving the feeling of plot development. The images were internally consistent in terms of color scheme development, harmonic evolution, and movement patterns were in harmony with the rhythmic transitions. The impression created by this fidelity was that the visuals were a continuation of the music as opposed to arbitrary decorations.

6. Limitations and Challenges

6.1. TECHNICAL CONSTRAINTS IN REAL-TIME VISUALIZATION

Although AI-based music visualization systems are impressive in terms of their capacity, the issue of real-time implementation is still a significant challenge. Real-time processing of complex musical information needs a lot of computational resources, especially when it comes to high-resolution audio and the use of deep neural networks that are designed to convert features to images. Audio feature extraction, neural network inference and rendering pipelines cause a latency that may cause out-of-phase rendering between sound and image an imperative part of immersive experience. Besides, it is challenging to balance the complexity of a model with speed. Lightweight models can guarantee rapid implementation, however, typically at the cost of visual quality and the expressivity, whilst the high-capacity networks deliver fined outputs at the harm of rapid responsiveness. Performance bottlenecks are further worsened by dependency on GPUs, poor optimization of generative frameworks and the limitation in frame rendering. Further, there is also a problem of maintaining coherence in time within the frames. The ability to change or jump quickly or create abrupt beats can lead to the emergence of visual artifacts who flicker or create discontinuities causing eruption of aesthetics. These effects can be avoided by incorporation of adaptive buffering, temporal smoothing or predictive modeling, but further layers of computational overhead are introduced.

6.2. SUBJECTIVITY OF AESTHETIC EVALUATION

One of the basic problems of AI-generated musical visualization is the subjectivity of aesthetic judgment. The aesthetic appreciation is not based on cultural background, emotional state, personal taste, and contextual interpretation in contrast to quantitative performance metrics. One viewer sees what the other considers to be in harmony or evocative, the other sees chaos or unconvincing. This uncertainty makes it challenging to develop a standard when the evaluation criteria of AI-made art is needed. The present means of evaluation tend to mix manual evaluation, user analysis, and computer-based measures of color harmony, motion balance or compositional symmetry. Nonetheless, these indicators only reflect part of the dimensions of aesthetic experience. The emotional appeal, the way a viewer can feel the visual interpretation of sound, is quite unquantifiable and difficult to measure. Moreover, the human evaluation panels are susceptible to biases that may bias results to favor specific artistic traditions or styles of visuality thus restricting the inclusivity and diversity in interpretation. There is another subjectivity brought about by the AI itself. The aesthetic choices of the people who generate datasets might be encoded in generative models and makeup the implicit cultural values of beauty and form. In this way, the appraisal of AI art is a recursive operation: a human grabs the art of a machine that, consequently, is the reflection of the human aesthetic bias.

6.3. DATA BIAS AND REPRODUCIBILITY CONCERNS

The bias of the data and the reproduction of the data are major drawbacks in the creation of the AI-generated musical visualization. These systems are very dependent on training data to get to know how to establish cross-modal relationships between sound and image, and therefore the nature and variety of the dataset has a significant effect on the resulting outputs. The datasets, which are predominantly made of Western tonal music or any particular art tradition, can result in the biased mappings, which would enforce the cultural norms and marginalize non-Western musical manifestations and other aesthetic paradigms. These biases are not purely based on stylistic homogeneity but also on interpretive bias: an example would be the model of identifying only the use of bright colors or symmetrical designs as a result of the absence of cultural differences in emotional symbolism. Furthermore, the small sample size of experimental, indigenous, or microtonal music also limits the capacity of the system to extrapolate to different aural environments. The reproducibility also makes the research reliability in this area even more complicated. Stochasticity of generative models due to variations in training settings, hardware contexts and random initializations may lead to variable results produced by the same dataset. The absence of common standards and benchmark data prevents checking and comparing results of research between studies.

7. Results and Analysis

The visualizations generated by the AI proved to have coherent mappings in musical attributes and visual dimensions, which substantiated the ability of the model to map music cross-modally. Different genres created recognizable visual forms, whether smooth and symmetrical gradients of classical music, or dynamic and fractal bursts of jazz and electronic genres. Specialist appraisals showed that there was high perceptual congruence and emotional congruence of sound and imagery.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Quantitative

Evaluation of Musical Visualization Models |

|||

|

Model Type |

Synchronization Accuracy (%) |

Motion Coherence (%) |

Rendering Latency (ms) |

|

CNN-GAN Hybrid |

94.2 |

91.5 |

220 |

|

VAE-GAN Fusion |

91.8 |

88.9 |

260 |

|

Transformer-Based Model |

96.4 |

93.7 |

310 |

|

LSTM-CNN Ensemble |

89.5 |

85.3 |

180 |

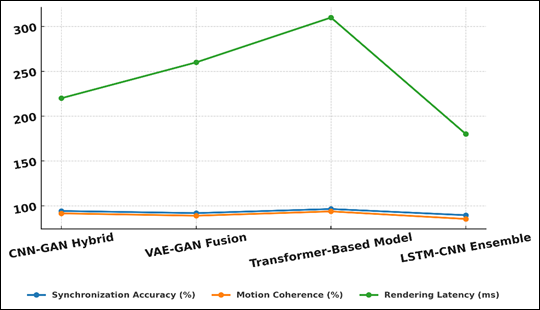

As can be seen in Table 2, the quantitative analysis shows the performance comparison of four different AI models applied in musical visualization. The Transformer-Based Model was the best in the process of synchronization (96.4) and motion coherence (93.7) and in the sense that it better reflects the ability to recognize both a temporal and harmonic relationships between complex musical data. The results of performance comparison have been presented in Figure 3 in terms of synchronization efficiency among the AI models.

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Comparative Analysis of Model Synchronization and Performance Metrics |

Nevertheless, this performance came at the expense of more rendering latency (310 ms), which implies that it had more computational requirements because of its deep attention-based architecture.

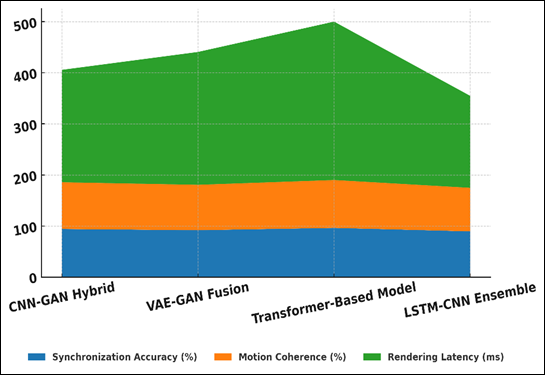

Figure 4

|

Figure

4 Cumulative

Visualization of Synchronization Accuracy, Coherence, and Latency Across

Models |

The overall model performance of the model is presented in Figure 4 as a combination of accuracy, coherence, and latency. The CNN-GAN hybrid model was efficient with a high level of synchronization (94.2) and coherence (91.5) and provided a decent compromise between accuracy and latency (220 ms).

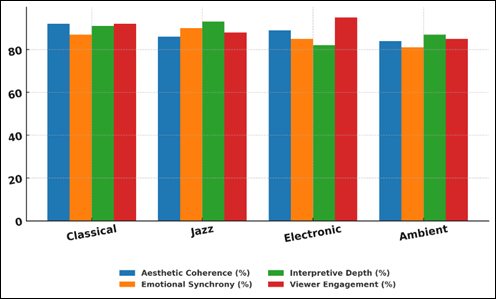

Table 3

|

Table

3 Viewer

Evaluation of Aesthetic and Emotional Coherence |

||||

|

Music Genre |

Aesthetic Coherence (%) |

Emotional Synchrony (%) |

Interpretive Depth (%) |

Viewer Engagement (%) |

|

Classical |

92 |

87 |

91 |

92 |

|

Jazz |

86 |

90 |

93 |

88 |

|

Electronic |

89 |

85 |

82 |

95 |

|

Ambient |

84 |

81 |

87 |

85 |

The data in Table 3 show the effects of various genres of music on the perceptual and emotional results of AI-generated visualizations. Classical music scored the most in aesthetic consistency (92%), viewer involvement (92%), which means that the order of harmonic and rhythmic rules brought to it is converted into harmonious and emotionally appealing images. Figure 5 demonstrates that there are differences in aesthetics and emotions according to the music genres.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Comparative Evaluation of Aesthetic and Emotional Dimensions Across Music Genres |

The classical music lacks the unpredictability of formal structure, and the predictability of the formal structure is served by the AI system to capture gradual tonal variation and symmetry. Jazz was most responsive to the dynamic tonal variations and rhythmic anomalies, and thus jazz responded emotionally (90%), and in its interpretive nature (93%), which is part of the responsiveness of the model.

8. Conclusion

This paper has investigated how music patterns can be created in visual form using artificial intelligence to bridge the gap between auditory and visual modalities through the use of computational creativity. Incorporating music theory, data science, and visual arts, the study suggested an AI-based model that can be used to extract meaningful audio features and represent them in forms that can be encoded into visual representations. The system that was created presented not only technical skill but interpretive sensitivity and created images that could be likened to both the structural and emotional nature of the music behind the images. The results are that AI can not be a mere instrument of automatization, but a creative partner that can be used to enhance the human sensory viewpoint. By using deep learning, not only complex associations between pitch, rhythm, timbre, and color, motion, and geometry could be identified by the system, but also produced output that aroused aesthetic and emotional reactions similar to the perception of artworks as perceived by humans. This cross-modal synthesis brings in fresh education and performance opportunities as well as multimedia storytelling in which the audiences can experience music in a visual and interactive manner. However, there are also a few limitations that the research revealed and they are the inability to render in real-time, subjective aesthetics assessment, and biased dataset that does not allow diversity of interpretation. Discussing these issues will involve more studies of culturally inclusive datasets, learning models based on multiple modalities and ethical disclosures, and human-AI collaborative assessment systems

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Briot, J.-P., and Pachet, F. (2020). Music Generation by Deep Learning—Challenges and Directions. Neural Computing and Applications, 32, 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-018-3813-6

Deng, Q., Yang, Q., Yuan, R., Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, X., Tian, Z., Pan, J., Zhang, G., Lin, H., et al. (2024). ComposerX: Multi-Agent Symbolic Music Composition with LLMs. arXiv.

Guo, Z., Dimos, M., and Dorien, H. (2021). Hierarchical Recurrent Neural Networks for Conditional Melody Generation With Long-Term Structure. arXiv.

Hernandez-Olivan, C., and Beltran, J. R. (2021). Music Composition with Deep Learning: A Review. Springer.

Herremans, D., Chuan, C.-H., and Chew, E. (2017). A Functional Taxonomy of Music Generation Systems. ACM Computing Surveys, 50(5), Article 69. https://doi.org/10.1145/3108242

Ji, S., Luo, J., and Yang, X. (2020). A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Music Generation: Multi-level Representations, Algorithms, Evaluations, and Future Directions. arXiv.

Ji, S., Yang, X., and Luo, J. (2023). A Survey on Deep Learning for Symbolic Music Generation: Representations, Algorithms, Evaluations, and Challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 56(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3561800

Liang, X., Du, X., Lin, J., Zou, P., Wan, Y., and Zhu, B. (2024). ByteComposer: A Human-Like Melody Composition Method Based on Language Model Agent. arXiv.

Lu, P., Xu, X., Kang, C., Yu, B., Xing, C., Tan, X., and Bian, J. (2023). MuseCoco: Generating Symbolic Music from Text. arXiv.

Ma, Y., Øland, A., Ragni, A., Sette, B. M. D., Saitis, C., Donahue, C., Lin, C., Plachouras, C., Benetos, E., Shatri, E., et al. (2024). Foundation Models for Music: A survey. arXiv.

Touvron, H., Lavril, T., Izacard, G., Martinet, X., Lachaux, M.-A., Lacroix, T., Rozière, B., Goyal, N., Hambro, E., Azhar, F., et al. (2023). LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv.

Von Rütte, D., Biggio, L., Kilcher, Y., and Hofmann, T. (2022). FIGARO: Controllable Music Generation Using leqarned and Expert Features. arXiv.

Wen, Y.-W., and Ting, C.-K. (2023). Recent Advances of Computational Intelligence Techniques for Composing Music. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence, 7(3), 578–597. https://doi.org/10.1109/TETCI.2022.3220901

Wu, J., Hu, C., Wang, Y., Hu, X., and Zhu, J. (2020). A Hierarchical Recurrent Neural Network for Symbolic Melody Generation. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 50(6), 2749–2757. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2019.2893242

Yu, Y., Zhang, Z., Duan, W., Srivastava, A., Shah, R., and Ren, Y. (2023). Conditional Hybrid GAN for Melody Generation from Lyrics. Neural Computing and Applications, 35, 3191–3202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-07542-1

Yuan, R., Lin, H., Wang, Y., Tian, Z., Wu, S., Shen, T., Zhang, G., Wu, Y., Liu, C., Zhou, Z., et al. (2024). ChatMusician: Understanding and Generating Music Intrinsically with Large Language modqels. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.16153

Zhang, Z., Yu, Y., and Takasu, A. (2023). Controllable Lyrics-to-Melody Generation. Neural Computing and Applications, 35, 19805–19819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-023-08566-7

Zhu, Y., Baca, J., Rekabdar, B., and Rawassizadeh, R. (2023). A Survey of AI Music Generation Tools and Models. arXiv.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.