ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Hybrid AI-Human Music Composition for Pedagogy

Paramjit Baxi 1![]()

![]() ,

Susmita Panda 2

,

Susmita Panda 2![]()

![]() ,

Sachin Mittal 3

,

Sachin Mittal 3![]()

![]() ,

Nidhi Tewatia 4

,

Nidhi Tewatia 4![]() , Battula Bhavya 5

, Battula Bhavya 5![]()

![]() ,

Fariyah Saiyad 6

,

Fariyah Saiyad 6![]()

1 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, 174103, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to Be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura-

140417, Punjab, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida

International University 203201, India

5 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering,

Presidency University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

6 Associate Professor, Bath

Spa University Academic Center RAK, UAE

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

will discuss how the hybrid AI-human music composition setting can have a

pedagogical effect on the creative process and musical knowledge of

undergraduate learners. They used a mixed-method research study that entailed

expert analysis of student composition, system interaction logs, and

reflective learner feedback. It was found that students with the hybrid

system obtained much better results in the increase of harmonic coherence,

melodic structure, rhythmic variation, and a general creative expression than

the control group with the traditional tools. Behavioral studies indicate

that AI-generated recommendations proved more helpful when composing the

first ideas, and students progressively used self-refinement in the later

stages of the composition. Evaluations of creativity levels and self-efficacy

scores among the experimental group had a significant positive change and

demonstrate the relevance of the system in increasing idea generation,

decreasing creative anxiety, and enhancing critical engagement skills. The

paper adds to a growing body of evidence that AI-assisted learning in a

hybrid form provides useful new directions in the field of music education,

helping to develop a more in-depth musical perception and more convenient

creative investigation. |

|||

|

Received 20 February 2025 Accepted 14 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Paramjit

Baxi, paramjit.baxi.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6695 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Hybrid Music

Composition, Generative AI, Pedagogy, Creative Learning, Music Education

Technology, Human-AI Collaboration, Composition Scaffolding, Educational

Creativity |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Hybrid AI-human Composition of music is establishing itself as an effective mode of teaching where computational creativity is introduced alongside human intuition which provides the learners with a dynamic means of perceiving, analyzing and composing music. Students who inhabit traditional classrooms are usually not able to connect the theory with the practice especially when they are to break the boundary between abstract music ideas and any meaningful composition. The use of artificial intelligence, in particular, deep learning-based and generative models, opens a new pedagogical level: they can create harmonic progression, melodic motifs, rhythmic variations, and patterns more than in the style, and students can promote, criticize, and enhance ideas in real time Zhao et al. (2025). Instead of substituting the creative agency of learners, these systems are catalytic partners that increase the creative palette of both novices and advanced learners. In hybrid model, AI is a musical partner, which listens. It provides immediate feedback on harmony, suggests counter-melodies and fits a selected genre, or suggests unpredictable chord substitutions that disrupt a student in his or her habits Wang et al. (2023).

Learners, by

their turn, assess, make amendments or dismiss these ideas, which foster a

creative process of reflection that builds up analytical and expressive

abilities. The process helps to accomplish an enormous variety of pedagogical

objectives, including instructing fundamental principles such as voice leading

and rhythm construction, as well as addressing more complex ones, such as

timbral design, modal substitution, or genre fusion Pinski et al. (2023).

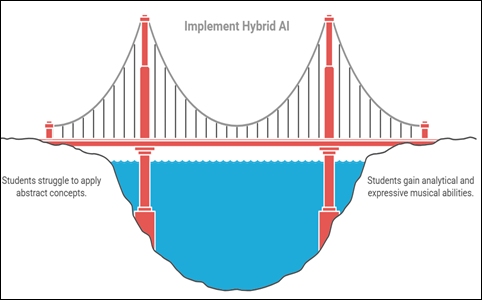

Figure 1

|

Figure

1

Interaction Flow

Between User, AI Model, and DAW Interface. |

Democratization of creativity in the classroom is also through hybrid AI-human music composition. Students who might not be adept at using instruments or written notation can still be able to engage in composition activities using the work of intuitive AI interfaces. Generative tools enable them to visualize chords charts, listen to the immediate interpretation of their thoughts, and experiment with numerous options without any technical limitations. On the other hand, more advanced learners are able to explore more in model customization, prompt engineering, or dataset curation, to explore how music structure is internalized in computational systems as represented in Figure 1. The openness to model behavior, e.g. showing attention maps or pattern alignments also encourages meta-cognitive learning, which assists students in knowing why certain melodies or rhythms appear when requested. With the move toward collaborative and experiential learning methods in education, hybrid classes of composition place music classesrooms in a role of exploratory studios in which machines and students actively co-create their creativity. Pedagogy can be transformed through the adoption of AI as a collaborative composer instead of a silent, but useful, back-end technology, into more personalized, interactive, and thoughtful types of musical education. What has come out is a more enriched landscape in which technology generates interest, students become more critical and composition has become an iterative experience that is approachable and not a big jump.

2. Literature Review

Artificial intelligence and music pedagogy intersect have grown at an accelerated pace in the last ten years due to developments in the field of machine learning, generative modeling, and interactive learning design. Initial algorithmic composition work was based on rule systems, which coded harmonic or contrapuntal principles into systems of symbols. Examples of these systems include generative grammars and Markov chains, which showed that computational processes could be used as imitators of stylistic regularities, but their significance as educational resources was only to provide an example of what can be done and what cannot. With the maturation of machine learning, scholars turned to the data-driven models that would be able to learn the musical structure directly out of corpora. RNNs should be noted as applying especially LSTMs to show greater stylistic consistency on melody and harmony creation, and this formed the basis of more responsive learning applications. With the development of deep generative models, a more radical change was presented. The expressive capabilities of algorithmic composition were increased with Variational Autoencoders and Generative Adversarial Networks, which allowed creating a longer musical phrase, a new timbral texture, and a stylistically consistent variation. Later on, architectures that focus on attention like Museet by OpenAI, Music Transformer by Google, and MusicMe by Meta enhanced the aspect of temporal coherence and the arrangement of multiple instruments. These systems emphasized the fact that AI can be used as a source of creative content, but also as a collaborator, which can generate music that is musically meaningful in real-time.

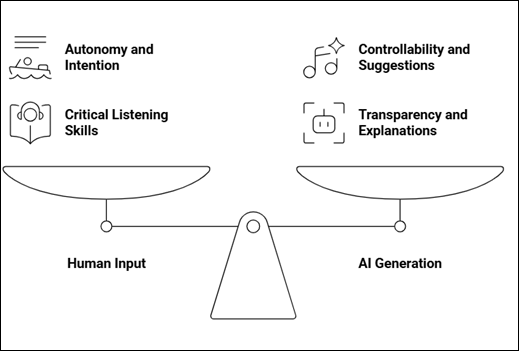

Figure 2

|

Figure

2 Balancing Human Interaction and AI suggestion

Pedagogy |

In education, these models facilitated new types of interaction through providing students with the ability to explore latent spaces, customize prompts, or refine outputs through several iterative cycles and providing learning opportunities. In line with the development of generative modeling, pedagogical studies have focused on digital technology technology to change the learning environment in music. Research on constructivist and experiential learning focuses on the fact that learners are most likely to learn through practical creative problem solving. The AI-based composition tools are in line with these frameworks because they allow learners to explore musical structures, judge system outputs, and consider the implications of their musical choices as shown in Figure 2. A number of studies pertaining to AI-assisted creativity in art and design education also indicate that hybrid systems do contribute to a better divergent thinking process and a more exploratory way of thinking. Intelligent tutoring systems have been used in music pedagogy in particular in tasks like rhythmic dictation, harmonic analysis and automatic accompaniment, and have shown significant improvements in engagement and conceptual understanding. The co-creativity of humans and AI is a recent topic in literature, which gives hybrid composition as a pedagogical tool a foundation. Co-creativity models focus on the mutualism between human contribution and algorithmic creation whereby both sides are involved in the end product of creative art. Students are found to gain when digital tools are balanced between autonomy and controllability, i.e. suggesting meaning without overpowering the human will. The interactive composition systems like CoCoCo by Magenta and the deep-learning-based DAW plug-ins, as well as examples of this principle, entail the student operation of the high-level musical properties, as the AI elaborates the generative output at a detailed level. Research is also keen on the significance of transparency in AI behavior as learners can develop better skills to employ critical listening when systems explain or visualize their decision-making processes within.

3. Proposed Design Methodology

The research design of the study will measure the effect of hybrid AI-human music composition settings and their effects on the conceptual authority, creative confidence, and development of compositional skills in the students. The research takes a mixed-method conceptualization of system design, classroom implementation, quantitative evaluation, and qualitative analysis to capture both experience and cognitive aspects of learning. The solution is consistent with the modern pedagogical frameworks focusing on experiential creation, repetitive feedback, and collaborative meaning-making between learners and computational systems.

Step-1 Educational Context and Participant Group

The sample was comprised of undergraduate students of music education who were taking a semester-long composition course. The learners had a mixed musical background which consisted of classical, contemporary and semi-formal music training. Before the study, every subject was tested in a baseline test of harmonic knowledge, ability to construct melodies, fluency in rhythm, and creative self-efficacy. A systematic tutorial was then used to introduce students to the hybrid composition system.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Participant Demographics and

Educational Background (Sample Data) |

||||

|

Variable |

Category |

Experimental Group (n = 22) |

Control Group (n = 21) |

Total (N = 43) |

|

Age (years) |

Mean ± SD |

20.9 ± 1.4 |

21.3 ± 1.6 |

21.1 ± 1.5 |

|

Gender |

Female |

12 |

10 |

22 |

|

Male |

9 |

10 |

19 |

|

|

Non-binary |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Primary Musical Background |

Classical |

9 |

7 |

16 |

|

Contemporary/Pop |

7 |

8 |

15 |

|

|

Semi-formal Training |

6 |

6 |

12 |

|

|

Years of Music Training |

< 3 years |

5 |

6 |

11 |

|

3–6 years |

10 |

8 |

18 |

|

|

> 6 years |

7 |

7 |

14 |

|

|

Digital Music Production Experience |

Beginner |

11 |

12 |

23 |

|

Intermediate |

8 |

7 |

15 |

|

|

Advanced |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

|

Prior Use of AI Music Tools |

Yes |

4 |

3 |

7 |

|

No |

18 |

18 |

36 |

|

The group was split into two groups; an experimental one applying the AI-assisted environment and control one applying the traditional composition instruments like software and keyboard instruments. The same learning goals, assignments, and rubrics of evaluation were given to both groups so that there would be no disparity in curricular expectations.

Step -2 Learning Tasks and Data Collection

The four scaffolded composition tasks were given to the participants based on the pedagogical areas integrated into the system. The students were supposed to present two versions of their work, firstly a draft and, secondly a final revised composition. The revision process involved the interactions of the experimental group with the generative AI model, but the control group revised manually with the help of the instructor and personal practice.

Three channels were applied to gather data:

· Compositional Artifacts: Early and late versions were evaluated on musical rules like structural consistency, harmonic precision, thematic progression and rhythmic consistency.

· Interaction Logs: System generated logs gave details on the frequency of interaction with the AI model, types of prompts students gave, and number of modifications made to material proposed by AI.

· Learner Reflections: Post task surveys and reflective journals reflected the perceptions of students regarding the aspects of creativity, confidence, collaboration, and cognitive load.

Step -3 Analytical Approach

Quantitative data involved rubric grading of compositions, scores on creativity rating, and statistical comparison of performance between the control and experimental groups involving the use of paired sample t-test and ANCOVA where necessary. A panel of qualified teachers who had no knowledge of the group work analyzed creativity and musical coherence. Descriptive statistics and behavioral clustering were used to analyze the real-life interaction logs, to determine patterns like prompting exploration, cycle of refinement or too much reliance on AI recommendations. Thematic coding of qualitative reflections revealed the perceived advantages and conflicts of working with AI that included motivation shifts, self-expression changes, and training of critical listening abilities.

The holistic nature of the triangulation of all the data sources facilitated a holistic understanding of the impact of hybrid AI-human composition on musical learning. The approach utilizes a combination of computational traces, expert analysis, and learner voice to help achieve an elaborate explanation of how co-creative technologies change the compositional process in educational activities.

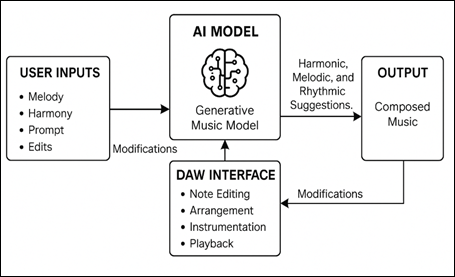

4. System Architecture and Tool Integration

This paper employs a hybrid environment of composition combining a generative music model by using transformers and an interactive digital audio workstation (DAW) extension. Harmonic exploration also increased, but less dramatically, potentially due to the fact that harmony is more dependent on explicit theoretical knowledge, which AI suggestions do not have the capability to displace. The scores of creative self-efficacy were also higher in students of the experimental group who explained the greater confidence by the iterative feedback loop which was made possible by the AI and DAW interface. Taken together, the results indicate that AI-human composition systems with a hybrid nature have the potential of adding a lot of depth to music pedagogy provided they are set up in a way that encourages reflective engagement, successive refinement, and learner agency. The system does not reduce creativity, but it opens up more discoveries of possibilities and allows a more subtle approach to compositional ideas. These findings highlight the educational importance of considering the work of AI as a dynamic partner that provokes, disputes, and leads the learner through the compositional process without losing the elements of human intentionality in the center of creative expression. The interface of the DAW enables students to edit, overlay and criticize the materials produced by AI by using functions like editing notes, tempo, instrumentation, and re-arranging the structure as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

|

Figure

3 Proposed Hybrid AI-human music composition

workflow |

The architecture was set up to accommodate four pedagogical tasks, namely: (1) harmonic exploration, (2) melodic development, (3) rhythmic variation and (4) full-piece co-composition. In every activity, the learner is tasked with generating ideas, being presented with AI suggestions and refining the output. Interaction data such as the type of prompts, the frequency of edits, acceptance or rejection of AI suggestions and time of each revision process is logged by the system.

5. Results and Discussion

The findings of the research indicate that hybrid AI-human composition environment has a significant positive influence on the music cognition, confidence in creativity, and the quality of composition of learners. In the four, structured tasks, the students in the experimental group had shown improvement in the first and final drafts more than the control group. The final compositions of the experimental group were rated by expert evaluators who were not aware of group assignments with more harmonic coherence, thematic continuity, and stylistic consistency. The results of these findings reveal that the existence of an adaptive generative model does not only increase the refinement process, but also the capacity of the students to internalize the complex music structures.

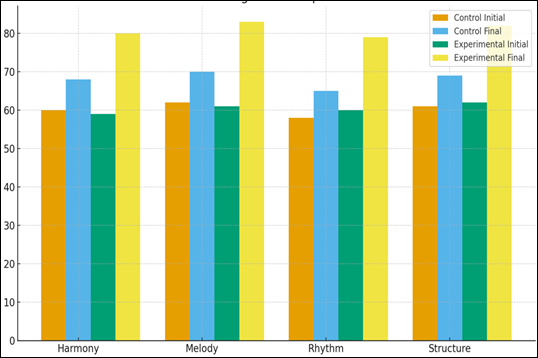

Figure 4

|

Figure

4

Learning Gain

Comparison (Bar Chart) |

The learning gain comparison chart shows the manner in which the two groups developed in the four major musical dimensions of harmony, melody, rhythm, and structural organization. Where the control group makes slight gains in first to final submissions, the experimental group has significantly more gains in all categories. The final scores of the experimental group soar high above their original scores and those of the control group particularly in melodic development and rhythmic variation. This aesthetic pattern indicates that the hybrid AI-human composition study process exerted an imminent influence on the capacity of students to polish and develop their musical concepts as illustrated in Figure 4. The greater increase in performance suggests that it is not just that technical accuracy is increased, but that the compositional ideas are in a more internalized state with the assistance of the generative feedback loops allowed by the system. Interaction logs also help to learn how students interacted with the system. Trends indicate that early on, the AI model was actively employed by the learners to produce chord progressions or melodic variations and that gradually, it is used selectively and critically in composition at later stages. Such a change in behavior is indicative of AI acting as a catalyst to creativity and not a crutch. Learners started with a leaning on generative suggestions and used it more and more as the output was refined, an increase in the use of their own musical judgment; showing that the hybrid system is capable of scaffolding autonomy. There is also a correlation of lower acceptance of the raw AI suggestions and higher scores of the experts that will also prove the point according to which the most efficient learning process will be achieved when the students are able to negotiate and critique the ideas of the algorithm rather than passively accept and use them.

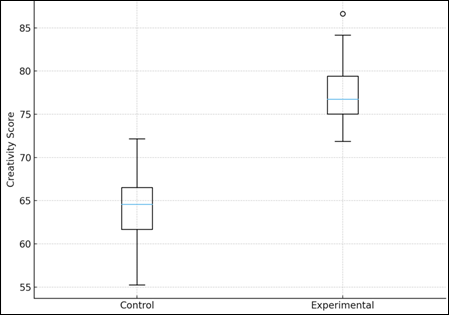

Figure 5

|

Figure

5

Creativity Rating

Distribution (Box Plot) |

This interpretation is supported by qualitative reflections. Numerous respondents attributed the AI to broadening their idea space, pushing them out of habitual ruts, or showing them harmony directions that they would not have explored on their own as shown in Figure 5. Creative anxiety was also noted to be reduced by students, especially at the lower stages of drafting since the system created immediate opportunities to respond to as opposed to students having to contend with a blank piece of score. But there were some learners who expressed a kind of waryness about over-reliance on the generative content, who said that they found the thrill of immediate output to be tempting to them occasionally, and that this might cause them to forget about to think deeply. This contradiction brings into light the significance of starting to explicitly learn critical engagement skills when adopting AI models into compositional pedagogy. The box plot of creativity rating indicates that there are distinct variations in how the scales of creativity assigned by the experts are distributed across the control and experimental groups. The experimental group has a greater median score and narrower interquartile range which indicates more robust and more consistent creative work. On the contrary, the more spread out distribution and lower median of the control group demonstrate more variability and less high-performing submissions. It is important to note that there are also fewer low outliers in the experimental group, showing that all the students, almost, were supported by the scaffolding of the hybrid system, which boosted the average level of creative performance. Such trend helps to conclude that AI-aided exploration enhances the creative process through generative impetus and expands expressive options of students.

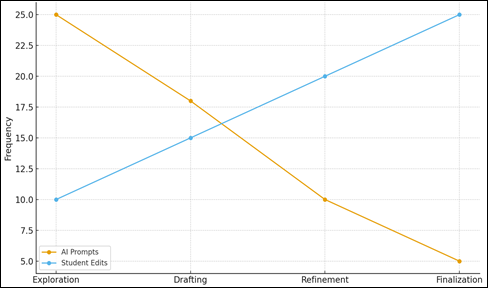

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Interaction Pattern Analysis (Line Graph) |

The graph of interaction pattern demonstrates the development of behavior among the students in the four stages of composition. In the initial exploration, learners would depend on AI-generated suggestions to initiate initial ideas. Nevertheless, as they advance to drafting, refining and finalizing, the rate of AI prompts slows down drastically. Simultaneously, student edits grow, finally arriving at a point where it is completely overtaken by AI interactions as shown in Figure 6. This pattern of crossing shows that there is a significant pedagogical pathway: initially, students rely on AI as a creative triggering device, though, over time, they tend to rely on their own taste in music. In the last phase, learners have the greatest autonomy of making decisions. The fact line graph serves to capture the nature of effectiveness of the hybrid model- AI generates early ideation and students progressively assume control of the compositional process.

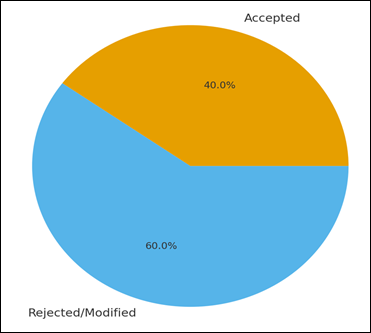

Figure 7

|

Figure 7

Acceptance vs

Rejection of AI Suggestions (Pie Chart) |

In the acceptance- rejection pie chart, it is indicated that 60 percent of AI-generated content was rejected or edited by the students, with only 40 percent being accepted directly. This balance shows that students did not passively depend on the AI outputs, but rather were critical in the way they interact with the generative suggestions as shown in Figure 7. The high level of edits and rejection is the indicator of the success of the hybrid system in developing evaluative thinking, developing a system that is able to make students evaluate the appropriateness of generated ideas and make a choice related to creative intentions. This conduct is compatible with the higher-order thinking in composition pedagogy, where students should not just accept the shallow recommendations but create deliberate musical results.

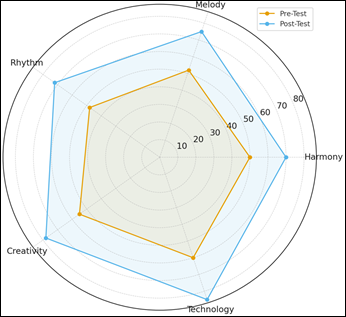

Figure 8

|

Figure

8

Self-Efficacy

Radar Chart (Pre-test vs Post-test Scores) |

The self-efficacy radar chart reveals a straight and steady growth in all five aspects of musical confidence, which include harmony, melody, rhythm, creativity, and technological ability. The level of confidence was moderate among students before applying the hybrid system especially in rhythm and melody composition. Once the tasks are done with the help of AI, the post-test scores improve significantly as shown in Figure 8 and appear in a wider and enlarged form across the axes. The largest improvements are in the domains of creativity and technological confidence, which represent simplies that hybrid composition classrooms do not only enhance the musical performance, but also make students believe in their creative abilities, which is a crucial element in the creative development in the long term. The comparative analysis between groups shows that the hybrid model made the greatest contribution to the advancement of melodic development and rhythmic variation. The possibility of the AI to quickly generate motif substitutes allowed the students to explore the contour, phrasing and syncopation more liberally than in the standard workflows.

6. Conclusion

This paper shows that AI-based music composition that employs humans as active participants has significant pedagogical advantages, in terms of broadening the creative abilities of learners, increasing their conceptual knowledge, as well as in their confidence in the composition procedure. Students using the generative system showed better improvement in accuracy in harmony, melodic development, rhythmic variation, and coherence in the structure in contrast to students using traditional tools only. The analysis of interactions showed that AI support was the most effective at the stage of early ideation and that the learners progressively responded to their own judgment at the refinement stages-this is a healthy development of dependence to autonomy. Qualitative considerations also made it clear that AI was not a substitute of creativity but rather a stimulus that expanded imagination of students and decreased creative stagnation at the initial stages of development. The work regarding the long-term learning results and the adaptation of hybrid models to various musical traditions and learning settings should be pursued in the future.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Agostinelli, A., Et Al. (2023). Musiclm: Generating Music From Text (Arxiv:2301.11325). Arxiv. Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/2301.11325

Briot,

J.-P., Hadjeres, G., And Pachet, F.-D. (2017). Deep Learning Techniques

For Music Generation: A Survey. Arxiv. Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/1709.01620

Brunner, G., Konrad, A., Wang, Y.,and Wattenhofer, R.

(2018). Midi-Vae: Modeling Dynamics and Instrumentation Of Music With

Applications to Style Transfer. Arxiv. Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/1809.07600

Chen,

J., Tan, X., Luan, J., Qin, T., and Liu, T.-Y. (2020). Hifisinger:

Towards High-Fidelity Neural Singing Voice Synthesis. Arxiv.

Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/2009.01776

Chu,

H., Et Al. (2022). An Empirical Study on How People Perceive

Ai-Generated Music. In Proceedings of the Acm International Conference on

Information and Knowledge Management (Pp. 304–314). Acm.

Https://Doi.Org/10.1145/3511808.3557278

Conklin, D. (2003). Music Generation from Statistical Models. in Proceedings of the Aisb Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Creativity, Arts and Science. Society for the Study Of Artificial Intelligence and Simulation of Behaviour, 30–35.

Copet,

J., Kreuk, F., Gat, I., Remez, T., Kant, D., Synnaeve, G., Adi, Y., And

Defossez, A. (2024). Simple and Controllable Music Generation

(Arxiv:2306.05284). Arxiv. Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/2306.05284

Cross, I. (2023). Music in the Digital Age: Commodity, Community, Communion. Ai And Society, 38, 2387–2400. Https://Doi.Org/10.1007/S00146-022-01517-5

Cifka, O., Simsekli, U., and Richard, G. (2020).

Groove2groove: One-Shot Music Style Transfer With Supervision From Synthetic

Data. Ieee/Acm Transactions On Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, 28,

2638–2650. Https://Doi.Org/10.1109/Taslp.2020.3017211

Deruty, E., Grachten, M., Lattner, S., Nistal, J., and

Aouameur, C. (2022). On the Development And Practice of AI Technology

For Contemporary Popular Music Production. Transactions of the International

Society for Music Information Retrieval, 5(1), 35–50.

Https://Doi.Org/10.5334/Tismir.121

Herremans,

D., Chuan, C.-H., and Chew, E. (2017). A Functional Taxonomy of Music

Generation Systems. Acm Computing Surveys, 50(5), Article 69.

Https://Doi.Org/10.1145/3108242

Huang,

Q., Et Al. (2023). Noise2music: Text-Conditioned Music Generation With

Diffusion Models (Arxiv:2302.03917). Arxiv.

Https://Arxiv.Org/Abs/2302.03917

Pinski,

M., Adam, M., and Benlian, A. (2023). AI Knowledge: Improving AI Delegation

Through Human Enablement. In Proceedings of the Chi Conference On Human Factors

In Computing Systems (Pp. 1–17). Acm.

Https://Doi.Org/10.1145/3544548.3580934

Wang, T., Diaz, D. V., Brown, C., and Chen, Y. (2023).

Exploring the Role of AI Assistants in Computer Science Education: Methods,

Implications, and Instructor Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Ieee Symposium

on Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing (Vl/Hcc) (Pp. 92–102). Ieee.

Https://Doi.Org/10.1109/Vlhcc57795.2023.00021

Zhao, Y., Yang, M., Lin, Y., Zhang, X., Shi, F., Wang,

Z., Ding, J., and Ning, H. (2025). Ai-Enabled Text-To-Music Generation:

a Comprehensive Review of Methods, Frameworks, and Future Directions.

Electronics, 14(6), 1197. Https://Doi.Org/10.3390/Electronics14061197

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.