ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

The Cinematic Canvas: A Comprehensive Exploration of Cinema as a therapy, Effect of Film on Emotional Insight, Healing, and Personal Wellbeing

Dr. Prabakaran V.1![]() , P. S. Padmavathy 2

, P. S. Padmavathy 2![]()

1 Professor and Head - School of Media Studies, Faculty of Science and Humanitie, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram, Chennai, India

2 Ph.D. Research Scholar- Part Time Internal, Assistant Professor, Department of Visual Communication, Faculty of Science and Humanitie, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram, Chennai, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Cinematherapy,

also known as film therapy or movie therapy, was formally coined by

Berg-Cross, Jennings and Baruch

(1990) is a therapeutic approach that utilizes the

power of cinema to promote emotional healing and personal growth. This

innovative approach draws upon various psychological theories, including

psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioral theory, and humanistic theory, to help

individuals explore their emotions, gain new perspectives, and develop coping

skills. This study provides a comprehensive review of the theoretical

foundations, historical roots, and practical applications of cinema as a

therapeutic tool. Through a critical analysis of existing literature and

empirical studies, this study aims to contribute to the growing body of

research on cinematherapy and its effectiveness in promoting mental health

and well-being. The findings suggest that cinematherapy can be a valuable

adjunct to traditional psychotherapy, offering clients a unique and engaging

way to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Further research is

needed to fully understand the potential of cinematherapy and its role in

enhancing therapeutic outcomes. |

|||

|

Received 10 January 2025 Accepted 21 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. V.

Prabakaran, prabakav3@srmist.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6688 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cinematherapy, Emotional Healing, Personal Growth,

Film Therapy, Mental Health, Psychotherapy, Well-Being |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Cinema is widely recognized as a captivating storytelling medium that surpasses language, cultural, and educational barriers. Its blend of visuals and narratives makes it inclusive, appealing to diverse audiences across various socio-economic backgrounds and age groups Swetachandan (n.d), IELTS.net, n.d.). This universal appeal makes cinema a powerful platform for sharing ideas, emotions, and perspectives.

From its early days, cinema has played a significant role in shaping societal norms, values, and attitudes. It has the power to influence public opinion on a variety of issues, including politics, culture, and social justice SelvarajVelayutham et al. (2021). From Annadurai to Karunanidhi, M. G. Ramachandran, and Jayalalithaa, Tamil Nadu politics has been deeply shaped by cinema. Annadurai and Karunanidhi used movies to propagate Dravidian ideology and cultivate cinema audience into voters, MGR converted his heroic screen persona into political capital as Chief Minister, and Jayalalitha drew on her cinematic charisma to achieve electoral dominance SelvarajVelayutham et al. (2021). Through its storytelling, cinema can evoke empathy, provoke thought, and inspire action, making it a powerful tool for social change Reddan et al. (2021). The film industry, with its vast resources and global reach, has become a key player in the realm of mass media Miller and Stam (2004). Films not only entertain but also educate and enlighten audiences about various societal issues. They serve as mirrors that reflect the realities of the world, both past and present Monaco (2009).

Cinema serves as a powerful platform for shedding light on critical social issues, effectively raising awareness and catalyzing change Kapur and Wagner (2011). Over the years, films have tackled a wide array of topics, ranging from poverty and discrimination to environmental degradation and mental health Karmakar et al. (2025). Through their narratives and visuals, these films have succeeded in sparking meaningful conversations and driving societal transformations.

One of the key strengths of cinema lies in its ability to portray complex issues in a relatable and compelling manner Nyiramukama (2025). By presenting these topics through the lens of compelling stories and well-developed characters, films have the capacity to engage audiences on both emotional and intellectual levels Kaur and Bhatia (2022). This engagement is crucial, as it often leads to greater understanding, empathy, and a desire for change among viewers. Cinema's influence extends beyond mere entertainment; it is a dynamic and influential medium capable of shaping societal norms and values. This occurs in a process of narrative transportation, where the audiences become deeply connected with the storyline and characters Green and Brock (2000). Such connections and identifications can promote empathy for marginalised groups, alter impinged attitudes, and even motivate behavioural change. By presenting alternative perspectives and challenging the status quo, films have the power to shift collective consciousness and inspire behavioural change Tadayon Nabavi and Bijandi (2012).

Cinema transcends its role as mere entertainment, profoundly impacting society and shaping culture Priyanka et al. (2022). Since its inception, humans have continuously sought new forms of recreation, with cinema emerging as a groundbreaking discovery in this quest Martin Johnes (2020s). Serving as a mirror to society, cinema reflects its myriad joys, struggles, and complexities. Through this medium, audiences are exposed to stories that resonate deeply with their own experiences, stimulating a sense of connection and understanding Carlos (2022). By portraying diverse cultures, lifestyles, and issues, cinema promotes empathy and broadens audience perspectives Asha Priya Thangavelu (2020). It has the power to inspire change by shedding light on pressing social and personal issues and sparking meaningful behavioural changes. For instance, filmmaker VetriMaaran, a habitual smoker, revealed in an interview with Bharatwaj published in Film companion YouTube channel that after watching ‘VaaranamAayiram’ movie, he smoked one cigarette and never touched another, underscoring how cinema can catalyze deeply personal transformations Film Companion South (2023). Films have the ability to challenge societal norms and provoke thought, ultimately influencing the way we perceive and interact with the world around us.

Cinema serves as a window to different cultures, furthering a sense of global unity by offering audiences glimpses into worlds beyond their own Lee et al. (2017). These films introduce viewers to diverse perspectives, traditions, and ways of life, promoting empathy and understanding across borders Anugerahwati and Dewanti (2022). Movies exert a profound impact on culture, shaping values and beliefs while blurring the line between fiction and reality Hadrian Lynn (2023). Filmmakers and storytellers have the ability to leave a lasting impact on societal norms, challenging conventions and inspiring change Guo (2025). Iconic characters of movies have transcended the screen to become cultural symbols, admired for their bravery, resilience, and embodiment of moral values Lee (2025). Their stories resonate with audiences, leaving a lasting impression on popular culture. Cinema has played a pivotal role in driving social changes by spotlighting key movements such as the civil rights movement and advocating for LGBTQ+ rights, contributing significantly to their advancement Gao and Guintu (2025). Cinema's power as a tool for advocacy is evident, with filmmakers using their craft to address pressing issues and inspire positive change. Indian filmmakers utilise their narrative strategies to glint social awareness and shift cultural norms. Popular examples include 3 Idiots (2009), kaala (2018), and Jai Bhim (2021), highlighting cinema’s power to influence development and reform Bharti (2024) TriptiandKumari (2024). Documentaries, in particular, have been instrumental in raising awareness about climate change, urging individuals and governments to take action. Movies such as "The Vaccine War'' have also shed light on crucial healthcare issues, advocating for better treatment and acceptance, especially in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic. Through these examples, cinema continues to serve as a powerful medium for social impact and cultural transformation.

2. Positive Impact of Cinema

Movies can provide valuable insight and understanding. Different genres offer unique perspectives on human behavior and society. Each movie presents a unique viewpoint, offering viewers insights they may not have considered before Oliver and Bartsch (2010). This aspect of watching movies expands the understanding of the world around, enriching the lives with newfound knowledge and perspectives Hanich et al. (2014). Beyond entertainment and pastime, many people find watching movies a way to reduce stress and relax Hankir et al. (2015). Watching movies can help to get out of the problems as an alternative to anxiety loss. Watching movies can have a positive emotional impact, it can calm down and soothe. It reduces the stress within by lowering worry, and may turn all negative thoughts into the better, as long as it is enjoyable Pannu and Goyal (2025). It indicates the movie has encouraged the viewers to feel more positive and inspired. Strong characters from the movie can inspire the audience to do the same and can increase self-motivation to be solid and inflexible in dealing with all the problems Niemiec and Wedding (2014). For example, the character of KosaksiPasapugazh (Actor Vijay) in Nanban (2012) inspired many young audiences to pursue education with critical thinking and creativity rather than the usual education system. Similarly, ArunachalamMuruganantham’s portrayal in Pad Man (2018) empowered discussions around menstrual health, inspiring viewers to challenge taboos and walk towards social change. International films like The Pursuit of Happyness (2006), featuring Will Smith as Chris Gardner, highlight self-belief and perseverance, motivating the audiences to remain resilient during financial and personal struggles.

Watching and relating the character in a movie makes the audience feel good and get some cathartic effect to change their life Niemiec and Wedding (2014). Movies transform dry content into lively narratives, making it easier to understand and remember Bengtson (2009). Therefore, incorporating movies is a quick strategy to convey concepts in various academic fields such as history, philosophy, political science, and religion Boyatzis (1994). While emotionally captivating, movies also stimulate critical thinking, as viewers can interpret situations differently Boyatzis (1994). When used to stimulate open discussion, participants feel free to share their viewpoints because movies are impersonal, thus avoiding offense.

3. The term: Cinematherapy

Cinematherapy, also known as film therapy or movie therapy, is a creative and innovative approach to psychotherapy that harnesses the power of cinema to promote emotional healing and personal growth Berg-Cross et al. (1990). The use of films as therapeutic tools is rooted in the belief that movies have the ability to evoke strong emotional responses and can serve as a powerful medium for self-exploration and reflection Yazici et al. (2014). Over the past few decades, cinematherapy has emerged as a promising adjunct to traditional psychotherapy, offering individuals a unique and engaging way to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. In a controlled, single-subject interrupted time-series design study conducted by Powell and Newgent (2010) found that group sessions centered around The Lord of the Rings developed significant reductions in hopelessness among depressed adults. Despite its growing popularity, however, cinematherapy remains a relatively understudied area within the field of mental health Sharp et al. (2002). This study seeks to contribute to the existing literature by exploring the therapeutic potential of cinematherapy in the context of mental health treatment. In this article, the researcher provides a comprehensive review of the literature on cinematherapy, exploring its history, theoretical foundations, and practical applications of cinema in mental health interventions.

4. Historical Roots of Cinematherapy

The use of films as a therapeutic tool can be traced back to the early 20th century, with the emergence of cinema as a popular form of entertainment. However, it was not until the 1970s that cinematherapy began to be recognized as a legitimate therapeutic approach, thanks in part to the work of psychologists such as Robert E. "Bob" Kesten.

Movie therapy evolved from the concept same as bibliotherapy Stamps (2003), which uses books and reading in clinical application for therapeutic purposes. The term "cinema therapy" was coined in 1990 by L. Berg-Cross, P. Jennings, and R. Baruch. They defined it as a therapeutic technique where a therapist selects films to use for the treatment based on the person’s concern. These films can be viewed by the individual alone or with specific others as part of the therapeutic course.

Cinematherapy, rooted in bibliotherapy's use of book plots for therapy, leverages films and videos for more immediate and impactful results Berg-Cross et al. (1990). Since its earliest scientific study in 1974 ,cinematherapy has demonstrated effectiveness in treating various mental health conditions Morris et al. (1974), including eating disorders, anxiety, depression, Heston and Kottman (1997) and addiction .

Frann Altman, a psychologist and professor with over 20 years of experience using cinematherapy, stresses that it's more than mere entertainment. She describes in a study that cinematherapy is more than just entertainment. “It is not akin to a book club or chat group,” she explained, “it is a process where individuals interact with carefully chosen films that resonate with their personal experiences. They connect with characters and narratives, extract meaning, and reflect on how the stories mirror their own lives. Altman underlines that this introspective and emotionally engaging process needs the counseling of an experienced therapist.”

Clinical psychologist Gary Solomon, author of books on cinematherapy like "The Motion Picture Prescription," recommends viewers pay close attention to their connections with characters and plots. He suggests keeping a journal to record reactions, insights, and emotional responses during film watching. Reflecting on these insights can be beneficial when discussing them with a therapist. MediCinema, a registered charity based in the UK, installs cinemas within hospital buildings to screen films for patients, caregivers, and family members during the patient's hospitalization. Established in 1999, the first installation was at St Thomas' Hospital in London. This initiative aims to provide individuals with a reprieve from the isolation of hospital rooms and wards, offering them a period of entertainment and respite. According to the article, “Cinematherapy and Film/Video-Based Therapy – Your Digital Storytelling Project 2”, The Chicago Institute for the Moving Image (CIMI) employs film creation as a therapeutic tool for individuals undergoing treatment for depression, amnesia, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric illnesses.

A study by Vorderer and colleagues (2019) explored the impact of film on emotions and well-being, revealing that watching movies can positively affect mood and emotional regulation, thus promoting mental health. Zhang and colleagues (2021) conducted a study on the effects of film viewing on social cognition, finding that movies can enhance individuals' empathy and perspective-taking abilities. This highlights the film's potential to promote social awareness and compassion. Apart from studies and experiments, there are few websites that support and practice this therapy. A site named‘Cinematherapy’ dedicated to cinematherapy, using films to promote personal growth and healing. It provides resources on using movies as a therapeutic tool, including articles, book recommendations, and movie reviews. The site features a database of movie "prescriptions" categorized by theme, making it easy to find films for specific emotional needs. It also offers guidance on incorporating cinematherapy into therapy and using films for self-care and personal development. And also there is a YouTube channel ‘CinemaTherapyShow’ with millions of followers; it showcases the therapeutic effects of films through discussion between the Licensed therapist Jonathan Decker and professional filmmaker Alan Seawright.

5. Theoretical Underpinnings of Cinematherapy

Cinematherapy uses films to help individuals explore their emotions and cope with psychological challenges, and draws upon several theoretical frameworks to explain its effectiveness Fithri Ananda et al. (2022). Cinematherapy is informed by various psychological theories, including psychoanalytic (Dermer, S. B., and Hutchings, J. B. 2000), cognitive-behavioral Berg-Cross et al. (1990), and Social learning theories (Powell, D. A., Newgent, R. A., and Lee, S. M. 2006). From a psychoanalytic perspective, films are seen as powerful tools for accessing and processing unconscious thoughts and emotions Berg-Cross et al. (1990). Cognitive-behavioral theorists view films as a means of challenging and restructuring maladaptive thought patterns Sharp et al. (2002). Humanistic theorists emphasize the role of films in promoting self-awareness and personal growth Wedding and Niemiec (2014).

One key theoretical underpinning is psychoanalysis, particularly the work of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. Freud's concept of catharsis (Freud, S., and Breuer, J. 1895/2009), the release of pent-up emotions through art, aligns with the idea that watching films can provide emotional release and insight into one's unconscious mind. Jung's concept of the collective unconscious (Jung, 1934/1969) suggests that films can tap into universal themes and symbols that resonate with viewers on a deep, archetypal level.

Another theoretical foundation of cinematherapy is narrative psychology- The Stories Nature of Human conduct byTheodreR.Sabrin, which emphasizes the importance of storytelling in shaping our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Films, as narratives, can help individuals construct meaning from their experiences and develop a sense of coherence in their lives Sarbin (1986). This aligns with the concept of narrative therapy, which suggests that changing the stories we tell about ourselves can lead to personal transformation White and Epston (1990).

Cognitive-behavioral theory Sharp et al. (2002) also informs cinematherapy, particularly in its emphasis on changing maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors. By watching films that depict characters overcoming challenges or changing their perspectives, individuals can learn new coping strategies and ways of thinking about their own situations Powell et al. (2006). The theoretical underpinnings of cinematherapy highlight its potential to engage individuals on an emotional and cognitive level, providing them with new insights and perspectives that can facilitate personal growth and healing Solomon (1995).

6. Empirical Evidence on Cinematherapy

Experimental evidence supporting cinematherapy's effectiveness is growing, with several studies demonstrating its positive impact on mental health. A study 'Improving the Empirical Credibility of Cinematherapy:A Single-Subject InterruptedTime-Series' conducted by Michael Lee Powell et al. (2006)suggests that a structured, nondirective group cinematherapy intervention is statistically and clinically effective at decreasing hopelessness.

One study conducted by Zhang et al. (2021) found that cinematherapy can enhance empathy and perspective-taking abilities, highlighting its potential for promoting social awareness and compassion. Ari Khusumadewi1, Yeni Tri Juliantika (2018) conducted a study on The Effectiveness of Cinema Therapy to Improve Student Empathy by applying pre experimental design, the form of One Group Pretest-Posttest Design among students which concluded that the application of cinema therapy can improve the empathy of vocational students. Vorderer et al. (2019) conducted a study on the impact of film on emotions and well-being, discovering that watching films can positively affect mood and emotional regulation. This study highlights the potential of cinematherapy to promote mental health and well-being.

The research study titled "Through the Looking Glass: A Scoping Review of Cinema and Video Therapy" examined 38 studies to explore how cinema or videos are utilized by researchers and therapists to address psychological and physical challenges in clinical and subclinical populations. The study aimed to categorize methodological approaches and outcome measures used in these therapies, with the goal of standardizing these techniques for future research and practice. Among 38 studies, 7 studies is on classic cinematherapy which delivered positive results, such as positive repercussions on the patient’s daily life, reflecting better on the situation and increased their awareness, becoming aware of the nature of their problem and speaking positively about them and also a study by Egeci and Gencoz (2017) suggested that the discussion phase is more effective than viewing phase.

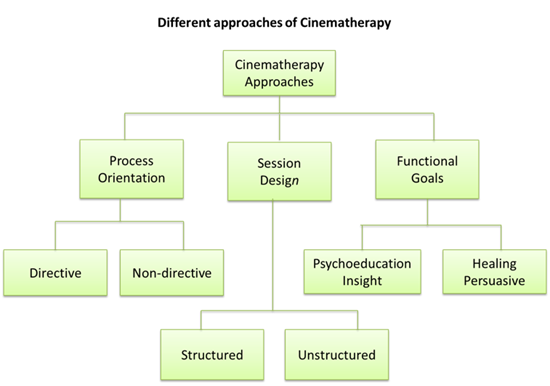

7. Practical Approaches of Cinematherapy

Cinematherapy can be used in a variety of therapeutic settings, including individual counseling, group therapy, and workshops Dermer and Hutchings (2000a). Therapists may use films to help clients explore and process emotions, gain new perspectives on their experiences, and practice new coping skills Powell (2006). Films with therapeutic themes, such as those depicting recovery from trauma or overcoming adversity, are often used in cinematherapy Hesley and Hesley (2001). The applications listed below are based on formal training and almost a decade of experience in providing cinematherapy, critical reviews of a number of documented cinematherapy case reports, and interviews with several leading cinema therapists Hesley and Hesley (2001).

Non directive vs. Directive Counseling Approach: Kottler and Brown (2000) in his book ‘Introduction to therapeutic counseling’ explain that directiveness involves one's ability to influence individuals in such a way that they are motivated to make positive changes. The practitioners using directive orientations may take initiative, set limitations, construct the sessions, offer suggestions, and assert their expert position so that positive therapeutic gains are possible. Nondirective practitioners, on the other hand, prefer that the client take charge and direct the therapeutic movement. In regards to cinematherapy, practitioners can apply a cinematherapy intervention using either a directive or nondirective approach. When using a nondirective delivery method, the practitioner only processes with the client the metaphors found within the film (e.g., characters, plot, dilemmas) and refrains from connecting the information to the client's life. Rather, it is intended that the client will make that connection on his or her own and bring whatever he/she chooses to the table for discussion. A directive practitioner, on the other hand, helps facilitate that connection by pointing out with the client similarities between both the movie and his/her own life. In the tamil film, KaakaMuttai (Dir. Manikandan, 2015) where a counselor could guide viewers to see how the struggles of the young protagonists mirror their own challenges in life. On the other hand, a nondirective approach could be observed in the film KannathilMuthamittal (Dir. Mani Ratham, 2002) where viewers are encouraged to interpret the complexities of war, identity, and family bonds without explicit guidance. In the movie AzhiyathaKolangal Dir.BaluMahendra, (1979), a coming-of-age story about three adolescents, provides opportunities for viewers to recollect their own adolescence, sexual awakening, and emotional transitions without any counselor. Similarly, in the film Dear Zindagi Dir. GauriShinde, (2016) a therapist uses a directive approach when she helps the protagonist understand her past experiences by drawing parallels with her current life situations. Films such as Veyil Dir. Vasanthabalan, (2016) and Autograph Dir. Cheran, (2016) also lend themselves well to a nondirective approach, as viewers naturally engage with themes of guilt, nostalgia, loss, and relationships through their own experiences.

Structure Counseling Approach: According to Kerr (1986), structured counseling sessions are those in which the counselor presents or decides ahead of time what topics and issues need to be discussed. Essentially, structured counselors have an agenda or use particular techniques for the purpose of obtaining a particular outcome. Structured cinematherapy sessions are similar. The researcher using this approach intends for clients to process particular parts of a movie because he/she believes that those specific clips will have the most powerful therapeutic properties for a given client Powell et al. (2006). In the Tamil film "Kabali," directed by Pa.Ranjith, a structured approach might focus on scenes depicting the protagonist's fight against oppression, relating it to the client's own struggles. In contrast, an unstructured approach in "PariyerumPerumal" movie directed by Mari Selvaraj could allow clients to freely explore motifs of caste discrimination, justice, and resilience based on their own interpretations.

Psychoeducation Approach: This approach involves using films to educate clients about mental health issues, treatment options, and coping strategies. Example: The Hindi film TaareZameen Par (2007), directed by Aamir Khan, depicts the struggles of a young boy, Ishaan with dyslexia who is wrongly understood as lazy and not studious until a teacher who is compassionate about his work recognizes his condition. This film could be used in a psychoeducation approach to raise awareness about learning disabilities and the importance of early intervention and support. The Tamil film Mozhi (2007), directed by Radha Mohan, portrays the life of Archana, an enlivened woman who is mute and deaf and her bond with Karthik, a musician who later falls in love with her. This move could be used to educate viewers about social barriers, communication challenges and the importance of understanding and supporting individuals with such challenges. With appropriate references from various related studies, these cinematic texts can be corroborated as meaningful interventions in therapeutic and educational settings.

The Healing Approach: Films are used to provide relaxation and distraction, offering a temporary escape from stress or grief. Example: The Tamil film Super Deluxe (2029), directed by ThiagarajanKumararaja interweaves multiple storylines, including a group of boys concealing a tragic accidents, a former porn actress returning to her family, a transgender father meeting her son and a couple entangled in a night of chaos. This movie could be used in a healing approach, offering a blend of humor and drama to help viewers momentarily escape their own stresses and immerse themselves in the film's engaging narratives. The film Dangal (2016), directed by Nitesh Tiwari, visualizes the real story of wrestler Mahavir Singh Phogat and his daughters who overcome societal constraints and personal hardship to achieve international success. This movie’s inspirational tone, gender equality, perseverance and triumph against odds could be used in a healing approach to provide a positive and inspiring story that helps clients temporarily escape from their own challenges and feel uplifted and motivated.

The Insight Approach: This approach focuses on helping clients gain new perspectives and understandings about their problems. Example: the Tamil film KattradhuTamizh (2007), directed by Ram, depicts the battles of an educated but unemployed young man who becomes increasingly marginalized from present society. The film spotlights themes of identity crisis, economic disparity, and psychological breakdown, encouraging viewers to reverberate on the social neglect of marginalized individuals and the emotional toll of systemic inequalities. Another Tamil movie, 24 (2016), directed by Vikram Kumar, is a science fiction narrative focussed on the control of time through a time-traveling watch. Apart from the entertainment, the film Kindles deeper contemplation about fate, free will, and personal choices tempting viewers to consider how agency and decision-making shape one’s life trajectory. Similarly in AnbeSivam (2003), directed by Sundar C., the story follows two contrasting characters on a journey that gradually reveals unfathomed insights about compassion, humanism, and the meaning of life. With weaving humor, drama, and philosophical tinges, the film encourages individuals to reassess their own values and perspectives on human suffering and empathy. These Tamil films serve as catalysts for critical self-reflection, allowing clients to interpret their personal challenges in the light of broader existential and societal themes.

The Persuasive Approach: Films are used to challenge and change clients' beliefs or attitudes. Example: The Tamil movie Peranbu (2019) could be used persuasively to challenge societal norms and attitudes towards individuals with disabilities, promoting acceptance and understanding.

8. Conclusion

Cinematherapy emerges as a dynamic and promising approach in the field of mental health treatment, harnessing the emotive and transformative power of cinema to facilitate emotional healing and personal growth. The historical and theoretical exploration reveals a rich tapestry of influences, from psychoanalytic insights to cognitive-behavioral strategies, shaping the practice of cinematherapy. Practical applications demonstrate its versatility, offering a range of therapeutic possibilities in individual, group, and workshop settings. Empirical evidence underscores cinematherapy's effectiveness, showing positive impacts on emotional well-being and mental health. The ability of films to evoke empathy, inspire change, and provide insights into personal challenges is central to its therapeutic value. Despite its growing popularity, further research is needed to fully understand and harness the potential of cinematherapy. In conclusion, cinematherapy stands as a compelling and innovative approach, offering a unique avenue for individuals to explore their emotions, gain new perspectives, and enhance their overall well-being. As an adjunct to traditional psychotherapy, cinematherapy holds promise in enriching therapeutic interventions and contributing to the evolving landscape of mental health treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, H., Holloway, D., Zaman, R., and Agius, M. (2015). Cinematherapy and Film as an Educational Tool in Undergraduate Psychiatry Teaching: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Psychiatria Danubina, 27(Suppl. 1), S136–S142.

Ananda, F., et al. (2022). The Use of Cognitive-Behavioral Group Counseling Combined with Cinematherapy Techniques to Reduce Academic Anxiety. Jurnal Bimbingan Konseling. Universitas Negeri Semarang.

Anugerahwati, M., and Dewanti, S. T. (2022). Intercultural Communication Competence of Indonesian Undergraduate Students When Watching the Movie American History X. KnE Social Sciences, 7(7). https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v7i7.10658

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bengtson, T. J. (2009). Review of A Novel Approach to Politics: Introducing Political Science Through Books, Movies, and Popular Culture. Journal of Political Science Education, 5(2), 175–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512160902815910

Berg-Cross, L., Jennings, P., and Baruch, R. (1990). Cinematherapy: Theory and Application. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 8(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1300/J294v08n01_15

Carlos, R. (2022). Film and Social Change: Exploring the Influence of Movies on Society. CINEFORUM, 62(1), 13–18.

Dermer, S. B., and Hutchings, J. B. (2000a). Movies as a Vehicle for Teaching and Learning About Diversity. Teaching of Psychology, 27(3), 212–217.

Dermer, S. B., and Hutchings, J. B. (2000b). Utilizing Movies in Family Therapy: Applications for Individuals, Couples, and Families. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 28(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/019261800261734

Dumitrache, S. D. (2014). The Effects of a Cinema-Therapy Group on Diminishing Anxiety in Young People. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.342

Dumitrache, S. D., and Mitrofan, L. (2015). The Effects of Cinematherapy: Anxiety Diminution, Self-Esteem Development. (Publication details not specified).

Film Companion South. (2023, April 10). Vetrimaaran Reveals How Suriya’s Vaaranam Aayiram Triggered Him to Quit Smoking! YouTube.

Freud, S., and Breuer, J. (2009). Studies on Hysteria. Basic Books. (Original work published 1895)

Gao, M., and Guintu, E. (2025). LGBT Representation in Film and Media: Social Impact and Future Development—A Literature Review. ResearchGate.

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Guo, Y. (2025). The Significant form: Visual Symbols and Cultural Symbolism in Film. Francis Academic Press.

Hanich, J., Wagner, V., Shah, M., Jacobsen, T., and Menninghaus, W. (2014). Why We Like to Watch Sad Films: The Pleasure of Tragic Cinema. Poetics, 44, 116–131.

Hankir, A., Holloway, D., Zaman, R., and Agius, M. (2015). Cinematherapy and Film as an Educational Tool in Undergraduate Psychiatry Teaching: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Psychiatria Danubina, 27(Suppl. 1), S136–S142.

Johnes, M. (2020, April 15). Cinema as the Most Significant Invention in Recreation.

Jung, C. G. (1969). Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original Work Published 1934)

Kapur, J., and Wagner, K. B. (2011). Cultural Studies and Film Theory. Routledge.

Karmakar, S., Mukherjee, A., and Karmakar, S. (2025). Reflections of the Mind: Bengali Cinema and Mental Health. Bengal Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.25259/BJPSY_9_2025

Kaur, B., and Bhatia, A. (2022). Impact of Cinema on Levels of Empathy and Emotion Regulation in Artists and Non-Artists: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 10(3), 477–485. https://doi.org/10.25215/1003.047

Lee, S. L. (2025). Stellar Identities: Cinema’s Cultural Mirror. NumberAnalytics.

Lee, S.-A., Tan, F., and Stephens, J. (2017). Film Adaptation, Global Film Techniques, and Cross-Cultural Viewing. International Research in Children’s Literature. https://doi.org/10.3366/ircl.2017.0215

Mangot, A. G., and Murthy, V. S. (2017). A Multimodal and Integrative Medium for Education and Therapy. Annals of Indian Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4103/aip.aip_13_17

Monaco, J. (2009). How to Read a Film: Movies, Media, and Beyond. Oxford University Press.

Morris, L. W., Spiegler, M. D., and Liebert, R. M. (1974). Effects of a Therapeutic Modeling Film on Cognitive and Emotional Components of Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30, 219–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(197404)30:2

Niemiec, R. M., and Wedding, D. (2014). Positive Psychology at the Movies: Using Films to Build Virtues and Character Strengths (2nd ed.). Hogrefe Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1027/00449-000

Oliver, M. B., and Bartsch, A. (2010). Appreciation as Audience Response: Exploring Entertainment Gratifications Beyond Hedonism. Human Communication Research, 36(1), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01368.x

Pannu, A., and Goyal, R. K. (2025). Cinematherapy for Depression: Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Films in Mental Health Treatment. Journal of Psychology, 159(5), 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2024.2409227

Powell, D. A., Newgent, R. A., and Lee, S. M. (2006). Group Cinematherapy with Emotionally Disturbed Adolescents. Adolescence, 41(162), 453–466.

Priyanka, S., Garima, K., and Nagendra, K. (2022). Role of Films in Societal Change. Crescent Publishing Corporation.

Rivera, C. (2022). Film and Social Change: Exploring the Influence of Movies on Society. CINEFORUM, 62(1), 13–18.

Sarbin, T. R. (Ed.). (1986). Narrative Psychology: The Storied Nature of Human Conduct. Praeger.

Sharp, C., Smith, J. V., and Cole, A. (2002). Cinematherapy: Metaphorically Promoting Therapeutic Change. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 15(3), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070210140221

Smieszek, M. (2019). Cinematherapy as a Part of the Education and Therapy of People with Intellectual Disabilities, Mental Disorders, and as a Tool for Personal Development. Nicolaus Copernicus University.

Stamps, L. S. (2003). Bibliotherapy: How Books can Help Students Cope with Concerns and Conflict. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 70, 25–29.

Thangavelu, S. (2020). Film as a Reflection of Society: Reception of Social Drama in Tamil Cinema. In Handbook of research on social and Cultural Dynamics in Indian Cinema (pp. 42–56). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/9781799835110.ch004

Tripti, and Kumari, P. (2024). Transforming Narratives: The Role of Hindi Cinema as a Catalyst for Social Development. https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i1.2024.3771

Wedding, D., and Niemiec, R. M. (2014). Movies and Mental Illness: Using Films to Understand Psychopathology (4th ed.). Hogrefe Publishing.

White, M., and Epston, D. (1990). Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. W. W. Norton and Company.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.