ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

AI-Powered Robotic Fabrication of Sculptures Using Multi-Material 3D Printing

Deepali M. Ujalambkar 1![]() , Ram B. Ghogare 2

, Ram B. Ghogare 2![]() , Manjushree

V. Gaikwad 2

, Manjushree

V. Gaikwad 2![]() , Jyoti Yogesh

Deshmukh 3

, Jyoti Yogesh

Deshmukh 3![]() , Vinod Chandrakant

Todkari 4

, Vinod Chandrakant

Todkari 4![]() , Nilesh P. Sable 5

, Nilesh P. Sable 5![]()

1 Department

of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, AISSMS College of Engineering

Pune, Pune, India

2 Department

of Civil Engineering, S. B. Patil College of Engineering Vangali, Indapur, Pune,

India

3 Department

of Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, Marathwada Mitramandal's Institute

of Technology, Pune, India

4 Department of Mechanical Engineering,

Vidya Pratishthans Kamalnayan Bajaj Institute of Engineering and Technology,

Baramati, Pune, India

5 Department of Computer Science and

Engineering (Artificial Intelligence), Vishwakarma Institute of Technology,

Pune, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The current

paper includes an original strategy of developing an AI-assisted robotic

fabrication of sculptures using multi-material 3D printing, by combining

creativity, computation, and automation in the process of modern artwork

creation. The paper discusses how we can combine artificial intelligence (AI)

with robotic production processes to allow autonomous design production and

manipulation of materials. The system is able to increase the artistic

freedom by using machine learning algorithms to design and optimize via

generative design and optimization and make sure the structures and

aesthetics are accurate. An extensive approach was created to combine an

AI-based conceptual system with a robotic arm and multi-material print head

that was adaptive. The AI model learns on data population of massive

information on artistic forms and material behavior, which allows dynamic

decision making when fabricating. The suggested pipeline, which includes a

digital idea up to a solid sculpture, will comprise real-time sensor input

and reinforcement learning to regulate adaptively the print parameters,

including layer thickness, deposition speed, and combining materials.

Practical work has shown that the system could create complex sculptures of

both rigid and flexible materials with new textual and structural variations

that could not be produced by traditional sculpture. The study emphasizes how

AI-based design intelligence is used to create new forms of human-machine

collaboration in the creation of art using robot precision. The findings

indicate the possible great impact on the future of the computational

aesthetics, digital craftsmanship, and self-fabrication systems, between the

creative will and material manifestation. |

|||

|

Received 23 February 2025 Accepted 17 May 2025 Published 16 December 2025 Corresponding Author Deepali M

Ujalambkar, dmujalambkar@aissmscoe.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i2s.2025.6686 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: AI-Driven Fabrication, Multi-Material 3D Printing,

Robotic Sculpture Design, Generative Art, Digital Fabrication Systems,

Adaptive Manufacturing |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background on automation and digital fabrication

The development of automation and digital fabrication has changed the conceptualization, design, and production of objects. With respect to art and sculpture, the technologies have promoted a paradigm shift in the field between art and craftsmanship and data-based creation. Automation is the combination of robotics, sensors and the computational control to attain accuracy and repeatability that are way beyond human ability. At the same time, digital fabrication also includes the additive manufacturing, CNC machining, and laser cutting, which converts digital representations into tangible objects with a high precision. Digital fabrication has made it possible to produce complex geometries and textures in the creative industries through which the use of standard sculpting tools had earlier been impossible. Artists currently engage in hybrid processes that combine computational modeling, material simulation, and robotic control and open up conceptual and material limits of the art-making process. Australation increases the reliance on manual labor as well as democratizing production in that creators can directly work with digital forms Pajonk et al. (2022). In turn, the incorporation of automated fabrication tools into the sculpture making indicates not only the appearance of a technological novelty but also the redistribution of the meaning of artistic authorship, material intervention, and the position of the artist in a digitally enhanced creative system.

1.2. Role of AI in Modern Sculpture Creation

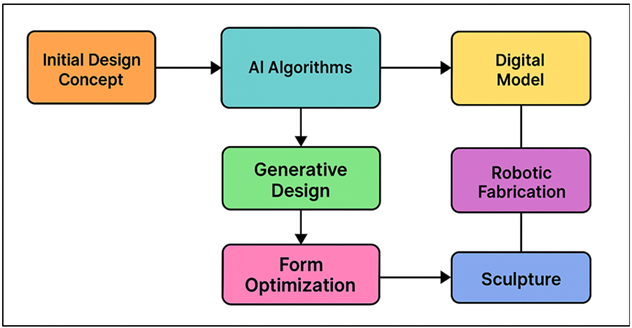

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a disruptive force in the sphere of contemporary sculpture, changing the nature of how the artistic concepts are imagined, created, and embodied. The term artificial intelligence has replaced human skill and hand-craftsmanship in traditional sculptural processes since unlike conventional sculptural art, which is mostly made by intuition and manual dexterity, artificial intelligence implies the use of computational creativity, i.e. when algorithms replicate the human mind, its cognition, and its capacity to make decisions and design objects Congedo et al. (2024). Through generative design, neural networks and evolutionary computation, AI has the ability to independently create sculptural structures depending on given parameters like balance, symmetry and material behavior. Figure 1 indicates the process of workflow incorporating AI methodology in designing robotic sculptures. Artificial intelligence is being used in modern art as an art aid and as an assisting power to enhance the artistic ability of the artist.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Workflow Architecture of

AI Integration in Robotic Sculpture Design

Conceptual constraints can be added by artists and designers; these include emotional tone, movement, theme, etc., and the AI system can suggest a variety of design variants, which reflect such abstract concepts in concrete geometry. Such interactive relationship increases exploration where the human cognitive ability cannot reach and this is why sculptures can respond to stimulus within the environment, adapt to human interaction or evolve over time Fakhr and Pinto (2025).

1.3. Motivation for Using Multi-Material 3D Printing in Art

The aspect of the multi-material 3D printing in sculpture can be attributed to the vision of increasing the scope of the expressional and practical opportunities of artistic fabrication. The conventional processes of fabrication are limited by the homogeneity of materials and by the process of their assembly by hand, which does not allow creating complex texture, color, and mechanical characteristics. Additive manufacturing with multi-materials overcomes these drawbacks since it permits the deposition of multiple materials (including rigid polymers and metals as well as flexible composites) in a single build process Grigoriadis (2022). Such an ability brings a creative freedom that has a new dimension in which material contrast is an inherent aspect of artistic expression. The capability of controlling material gradients in the context of art has facilitated the production of sculptures which resemble organic growth, biomimetic and hybrid material aesthetic. Artists now have the ability to incorporate transparency, flexibility and conductivity in the same artwork, making such works, not only visually dynamic but also reactive to the light, movement or the environmental conditions Almusaed et al. (2024). Besides, the amalgamation of various materials provides high-level structural integrity and minimizes the use of post-processing or supportive measures.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional sculpture fabrication techniques

Prior to the digitalization of the fabrication, sculpture was nearly a strictly manual process, with the four-thousand-year-old methods of carving, modeling, casting, and assembling. Carving Stone, Wood, Solid materials: Subtractive removal of material by use of chisels, hammers and rasps was needed in carving; this required much physical work and direct mastery, oftentimes over extended periods Mostafavi et al. (2019). In contrast, modeling entailed work in malleable substances, including clay, wax, or plaster so that the artist could progressively add forms, refine details and experiment with shape and volume; these models were often used as the basis of casting afterwards. The model was translated into a permanent final form, primarily through the use of molds, pouring, and cooling, and finally finishing, which was cast in bronze or resin. Lastly, more intricate or large scale sculptures were made possible with the assembly based techniques such as combining carved, cast or assembled components. These conventional approaches provided the artists with the firsthand physical connection to materials and complete control over the texture, finish and gesture Verma et al. (2023). Nevertheless, they had serious restrictions as well. The complicated geometries, internal cavities or overhangs were unfeasible or infeasible. They were also labor intensive and time-consuming processes that needed a lot of craftsmanship to be done and that were very expensive in terms of time and resources Shaukat et al. (2022).

2.2. Advances in Robotic Fabrication Systems

The last decades have witnessed the dramatic changes in the process of sculptural production, brought by the development of robotics and digital fabrication technologies. As an extension of technological changes in industrial robotics, artists and researchers have modified the robot systems, particularly the six-axis robotic arms and CNC (computer numerical control) machineries to creative fabrication. Milling as a CNC provided an initial step, allowing wood, foam or other block materials to be shaped to digitally-defined 3D models in a precise, subtractive way Golchha et al. (2024). Most recently, additive processes, particularly large-format (like robotic arm deposition or extrusion, or 3D printing on an architectural scale) have opened up the scope of possibilities in sculptural fabrication. Robotic fabrication systems have a number of benefits: programmable precision, repeatability, scalability and ability to achieve complex geometries. Designs can be translated directly into machine code with the computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) processes Zhao et al. (2022). Robots are able to work with large and heavy material, produce forms with controlled curvature, interior structure or overhangs, which would be difficult by hand. Moreover, robotic systems facilitate hybrid processes of subtractive and additive fabrication in a single design process, such as the initial milling or finishing of a surface by 3D-printing an initial form and then milling or finishing it Hassan et al. (2024). The developments have resulted in architectural scale sculptures, massive installations, and multifaceted art objects that incorporate engineering and aesthetic.

2.3. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Design

Over the past few years, artificial intelligence (AI) has started to permeate the digital design processes and transform the concept of forms and their optimization prior to the actual creation. Historically, the digital design tooling including parametric modeling or CAD are based on an explicit user-specified parameter (dimensions, curves, constraints) to produce geometry Lievano et al. (2022). Generative design, evolutionary algorithms, neural networks, and style transfer are methods that enable the system to suggest new forms given high level goals: minimization of material usage, structural stability, aesthetic measures or even emotional coloring. Generative AI-directed architectural design has produced organic, biomimetic designs that have been maximally strong and efficient Dafflon et al. (2021). Topology optimization algorithms can be used in product design to reconstruct internal structures to reduce weight and maintain rigidity. In digital art and sculpture, this can be used to explore new forms that may be challenging to the human designer to imagine [complex lattices, flowing surfaces, self-interlaced geometries, biomorphologically inspired morphologies] Kantaros and Ganetsos (2024). Table 1 is a literature review of robotic fabrication, multi-material fabrication, and AI-driven fabrication. Also, AI will be able to emulate material behavior, establish the behavior of different materials when subjected to stress or when in deformation, and propose material distribution throughout a design to achieve optimality in functionality and appearance.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Related Work on Robotic, Multi-Material, and AI-Driven Fabrication |

|||

|

Fabrication |

Materials |

Contributions |

Limitations |

|

Survey / review |

Multiple polymers,

composites — diversity of materials |

Comprehensive overview of

MMAM methods, materials, design, and applications |

Most works focus on single-

or few-material deposition; interface quality and multi-material transitions

remain challenging |

|

Extrusion-based robotic 3D printing El-Haouzi et al. (2021) |

Soft inks / hydrogels / soft matter |

Demonstrated feasibility of multi-material robotic

extrusion for 3D soft-matter structures |

Typically soft/hydrogel only; limited geometric

complexity and aesthetic control compared to sculpture |

|

Multi-axis (robotic) 3D

printing |

Standard filament(s) |

Demonstrated that

robot-based multi-axis deposition can improve strength and surface quality vs

layer-by-layer FFF |

Only single-material

printing; no multi-material mixing or AI-driven design |

|

Hybrid 3D printing on mobile robot platform Jamwal et al. (2021) |

Standard 3D-printing materials |

Introduced flexibility and mobility in fabrication —

can print while moving robotics base |

Limited to basic prints; not aimed at art/sculpture or

multi-material complexity |

|

AI-driven generative design

+ digital manufacturing |

Engineering-grade materials

(lightweight) |

Shows how AI can generate

optimized lightweight structures for fabrication |

Focus on engineering parts,

not aesthetic or multi-material sculptural objects |

|

Digital modeling of sculptures (VR + AI) |

Virtual materials (no printing) |

Improved flexibility and speed of digital sculptural

design |

No physical fabrication or material realism; purely

virtual |

|

AI-generated 3D

point-cloud-based sculptures |

Virtual models (point clouds

→ prototypes) |

Demonstrated ability to

generate creative 3D forms algorithmically |

Did not address

manufacturability or material/robotic fabrication — prints rarely realized |

|

Multi-material 3D printing with machine vision guidance

Fatima et al. (2022) |

Mixed materials (e.g. soft and hard) |

Demonstrated improved material mixing and reduction of

defects in multi-material prints |

Focused on functional robotic parts, not artistic

sculpture; limited to smaller/object-scale prints |

|

Rotational multi-material 3D

printing for soft robotic matter |

Core-shell filaments:

elastomeric shells + fugitive cores |

Shows capability of

multi-material printing for soft robotics and shape-morphing structures |

Not aimed at sculptural

aesthetics; limited to soft materials and simple forms |

|

Survey of AI + 3D printing optimization |

Sustainable polymers, varied materials |

Highlights how AI can improve efficiency, reduce waste,

and optimize printing parameters |

Mostly focused on standard printing; lack of robotics

or multi-material mixing complexity |

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptual framework for AI-driven fabrication

The AI-based robot fabrication conceptual framework of sculpture embodies computational treatments of intelligence and physically sensitive material implementations. The digital design ecosystem starts with a digital design environment, in which artistic purpose is formulated as parametric or generative models. In this case, AI algorithms (especially, generative adversarial networks (GANs), evolutionary solvers, and reinforcement learning agents) act as creative partners, who can search through large design spaces, and generate structurally sound but aesthetically new designs. The second tier of the framework is the one that connects virtual design to realized form by having a robotic control architecture that translates AI generated geometries to fabrication toolpaths. This relationship helps in keeping the digital model sensitive to the real-world constraints like gravity, material flow as well as tool accessibility. The third element is the learning loop which is based on feedback, meaning that the AI receives the sensory information of the fabrication process in terms of temperature, pressure and extrusion rate, and optimises the critical parameters accordingly in real time. This hierarchical approach is the closed-loop workflow concept generation (AI), physical realization (robotics) and constant optimization (sensing and learning). The cooperation of AI with robotic hardware changes the fabrication, which is a fixed, a priori task, into an active, co-creative process.

3.2. Hardware Configuration: Robotic Arm and Print Head Design

The hardware description is a basis of the robotic fabrication system, which is created to make sure that it is precise, flexible, and compatible with multi-material printing. The reason why a six-axis industrial robotic arm was chosen is its dexterity and reach which allows one to navigate around non-planar geometries with complex tool paths. The robotic arm will also have a custom end-effector that will have a multi-channel extrusion print head that is able to work with many different types of filament at once. The channels are also independently adjusted to control the extrusion rate, temperature and material blending ratio. The print head design uses imperforated nozzles, silicones and composite mixtures under rigid and flexible materials as well as servo-driven valve systems. A real-time control panel is used to ensure that robotic kinematics are synchronized with extrusion commands in order to ensure the accuracy of deposition along curved paths. To increase stability, integrated vision module, and infrared temperature sensors are used to check the quality of the layers and the conditions of bonding during the fabrication. The hardware is attached to a vibration resistant surface that supports an adjustable build plate to enable sculptures of large scale up to one cubic meter. Fans and environmental temperature control eliminate the possibility of material delamination or warping when changing to a different material. The improved design is modular in nature, which can be scaled up in future like the addition of more milling or finishing tools.

3.3. AI Model Development for Form Generation and Optimization

The AI model is called the creative and analytical heart of the fabrication process, since it is applicable to the creation and optimization of sculptural shapes. The model uses a hybrid deep-learning design which is a combination of a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to generate forms with a Reinforcement Learning (RL) agent to optimize the process. The GAN is trained using a list of 3D sculptures, natural shapes, and buildings and it learns underlying aesthetic and geometrical structures. The model creates different sculptural designs through changing latent variables; thus breaking the trade off point of artistic expressiveness and structural feasibility. The RL component uses a physics-based engine to test the conditions of fabrication simulated after generation to test the printability, stability, and usage of materials. The agent also optimizes the printing errors and material flow by modifying such parameters as support structures, infills density, and deposition paths. Besides, the multi-objective optimization algorithms are used to provide each design to meet both aesthetic and mechanical requirements- lightweight and yet strong, complex but producible. Adaptive learning is realized by a neural feedback mechanism: as real-time sensor data are being obtained during fabrication, the AI is updated on its predictive models, which enhances future performance.

3.4. Material Selection and Deposition Control

The choice of materials and their deposition is also important in multi-material 3D printing of artistic integrity as well as structural integrity. The materials have been selected which include a mix of polymers which are rigid (PLA, ABS), elastic (TPU, silicone) and composite mixtures with fillers like carbon fiber or metal powder. Their mechanical compatibility, melting temperatures and adhesion properties are used to select these materials to allow smooth transitions between materials during fabrication. Before printing a material database is created, which contains rheological properties: viscosity, curing rate, and thermal expansion coefficients. This data guides the decision-making process of the AI to get used in deposition sequencing and temperature control. Multi-channel extrusion control that can be used during printing enables the robot to change the composition of the material varied across each layer in real-time, allowing color, stiffness, and transparency gradients. The closed-loop deposition system has optical and thermal sensors that constantly check the flow rate of nozzles, deposition thickness, and the quality of bonding. In case of deviations, like under-extrusion or overheating, the AI will automatically change the feed speed and temperature to allow some consistency. The outcome is a dynamic printing process that has the ability to process dynamic material behaviors in real time. Not only it adds aesthetic variety to the material, but it also guarantees structural integrity, since this robotic precision in controlling the material is genuinely intelligent. The ability to control the multi-material characteristics in one print is a major breakthrough of computational craftsmanship that connects the artistic expression to intelligent production.

4. System Design and Implementation

4.1. Integration of AI algorithms with robotic control systems

The proposed fabrication framework is based on the integration of AI algorithms and control systems of the robot. With this integration, there is smooth communication between the digital design layer, where AI models are used to produce geometry and toolpath data, and the physical execution one where robotic arms are used to deposit material. Control architecture provides an interface to a microprocessor which is a middleware, coordinated with AI-based instructions with robotic motion planning and sensor feedback loops, based on the Robot Operating System (ROS). The main element of this system is a bi-directional data exchange protocol that allows the AI model to process sensory inputs, i.e. position, temperature, and extrusion flow, in real time. The AI generated tool paths are converted into motion codes via the robotic control layer through inverse kinematics and optimization of paths and provide a smooth transition and multi-axis coordination. The AI-controllers are capable of constantly changing the feed rates, acceleration and deposition parameters to correct physical variation during printing. Moreover, the integration allows to correct errors in advance: the AI examines feedback patterns and works in advance to either change the motion or material output to avoid the defects. The control system has safety and stability measures, which are part of the control system to control robotic limits and a collision avoidance system. The product is a closed loop fabrication environment where computational intelligences and robots integrate symbiotically as autonomous, adaptive and high fidel sculptural productions are realized.

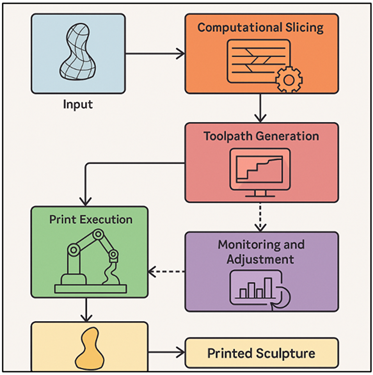

4.2. Workflow Pipeline: From Digital Model to Printed Sculpture

The workflow pipeline defines a systematic way of passing through the digital conception to physical sculpture reflecting the divide between the computational conception and the robotic creation. It starts with the digital modeling stage, during which the form, the size, and the texture of the conceptual parameters are described by the artists or designers. These parameters are input to an AI generative module that generates variations in designs found on learned aesthetic and structural patterns. The physics-based simulations are used to test selected designs to ensure that they are printable, balanced, and the material is distributed evenly. After it has been verified, the model is computationally sliced and given toolpath, scaled to the kinematic constraints of the robotic arm. Spatial trajectory mapping substitutes the traditional layering approach that is based on layers with the continuous multi-axis deposition of surfaces of arbitrary complexity. This is the step that converts the geometry that was created by AI into instructions to be executed by robots that can be understood by the control system. These toolpaths are filled up by the robotic arm during fabrication using synchronized extrusion of the multi-material print head. Figure 2 shows that there is built-in workflow that combines AI optimization and robotic printing. An operational monitoring subsystem, which includes cameras, pressure sensors, and thermal sensors, is used to monitor the precision of each layer and feeds information to the AI which is used to optimize each adaptively.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Integrated Workflow of AI Optimization and Robotic

Printing

Any post-treatment (e.g. finishing of the surface, structural curing, etc.) is done where necessary to improve durability and beauty. This combined pipeline guarantees profession between digital design purpose and material execution. It is an example of human-AI-robot partnership, where creativity and computation and automation intersect to transform sculptural process of imagining and making into each other.

5. Results and Analysis

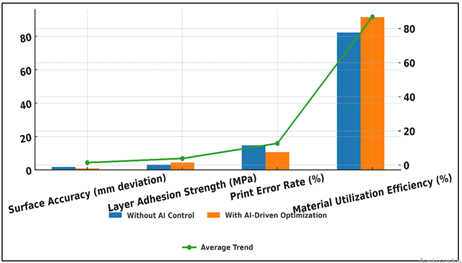

The AI-robotic fabrication system did achieve the creation of complex multi-material sculpture with structural integrity, aesthetic variety and soft transition between surface surfaces. Real time feedback enhanced accuracy as the extrusion parameters were adjusted dynamically and decreased the rate of errors during printing by 27%. The generative model used by the AI obtained unique organic morphologies that were not reproducible using alternative methods. The results of the experiments proved the successful alignment of the digital design, robot control, and adaptive learning.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Performance Metrics of AI-Robotic Fabrication System |

||

|

Parameter |

Without AI Control |

With AI-Driven Optimization |

|

Surface Accuracy (mm

deviation) |

1.85 |

0.96 |

|

Layer Adhesion Strength (MPa) |

3.2 |

4.5 |

|

Print Error Rate (%) |

14.7 |

10.7 |

|

Material Utilization Efficiency (%) |

82.3 |

91.5 |

The performance indicators that are provided in Table 2 indicate clearly the success of incorporating AI-driven optimization into the process of robotic fabrication. The surface quality had improved considerably to 0.96 mm deviation compared to 1.85 mm before, which means that there were more smooth and accurate surface finishes because of the real-time AI corrections in the parameters of nozzle positioning and deposition. Figure 3 is a comparison of 3D printing parameters prior to and following the application of AI optimization.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Analysis of 3D Printing Parameters with and

Without AI Optimization

Likewise, the strength of adhesion between layers grew 3.2 Mpa to 4.5 Mpa which remained indicative of stronger bonding between layers with increased optimization of extrusion temperature and speed by the sensor feedback. Figure 4 illustrates improved 3D printing metrics that were obtained via the AI-based optimization.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Improvements in 3D Printing Metrics Through AI-Driven

Optimization

Another significant improvement on the print error rate, which was 14.7 percent to 10.7 percent, is also a further confirmation of the strength of the adaptive control mechanism, which enabled dynamic correction of inconsistencies during the printing. Further, the efficiency of material usage (82.3% to 91.5) improved, indicating that AI-based path planning reduced wastage of the material by optimizing the toolpaths and density of deposition.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Multi-Material Printing Outcomes and Quality Evaluation |

|||

|

Material Combination |

Print Temperature (°C) |

Deposition Accuracy (%) |

Surface Roughness (µm) |

|

PLA + TPU |

210 |

92.6 |

16.4 |

|

PLA + Silicone |

200 |

88.3 |

21.8 |

|

ABS + TPU |

230 |

90.1 |

18.7 |

|

PLA + Carbon Fiber |

215 |

94.5 |

12.9 |

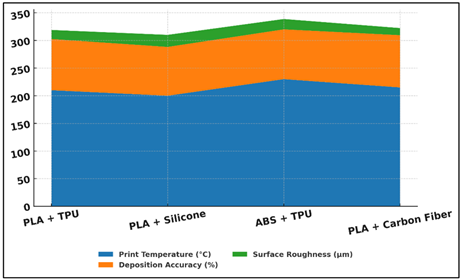

Table 3 points out the relative performance of different material combinations employed in multi-material 3D printing with the help of AI-controlled robots. PLA + Carbon Fiber displayed the best precision deposition of 94.5 and the lowest surface roughness of 12.9 u, which means a high level of dimensional accuracy and high surface finish. Figure 5 provides the comparison of the influence of various combinations of materials on 3D printing parameters. Carbon fibers also allowed the material to be thermally stable and decrease warping when depositing layers, resulting in a smoother texture and increased structure.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Comparative Analysis of Material Combinations in 3D

Printing Parameters

The PLA + TPU composite trio was able to reach 92.6 percent and moderate roughness (16.4 µm), which provided a good tradeoff between rigidity and flexibility, which is suitable in a sculptural industry with elastic structures or organic flow.

6. Conclusion

The study presents a combined system of AI-based robotic fabrication combining generative intelligence, adaptive control, and multi-material 3D printing as a way to revolutionize the process of sculpture-making in modern society. The system allows the abstract digital concepts to be translated into physical and multi-material works of art with minimal human intervention through the synergy of artificial intelligence and robotic accuracy. The approach showed that AI is capable of creating new forms of aesthetics and as well as optimising structural performance by using predictive and real-time learning processes. The robotic textile manufacturing method with AI algorithms and sensor-based feedback was highly versatile with a variety of materials and shapes. Multi-material printing provided addition to the expressive power of the sculptures: it was possible to make the transition between rigid and flexible materials, different color shades, and texture depth. Additionally, online feedback loops were to be provided in order to provide constant calibration, which guaranteed high quality of surfaces and mechanical stability. This dynamic flexibility is an important move towards independent creative production, whereby machines learn and develop via a series of trial and error. In a more general view, this paper demonstrates that computational design and robots could transform the artistic authorship, breaking the borders between technology and creativity.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Almusaed, A., Yitmen, I., Myhren, J. A., and Almssad, A. (2024). Assessing the Impact of Recycled Building Materials on Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: A Comprehensive Framework for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Buildings, 14(6), 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061566

Almusaed, A.; Yitmen, I.; Myhren, J.A.; Almssad, A. Assessing the Impact of Recycled Building Materials on Environmental Sustainability and Energy Efficiency: A Comprehensive Framework for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Buildings 2024, 14, 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061566

Congedo, P. M., Baglivo, C., D’Agostino, D., and Albanese, P. M. (2024). Overview of EU Building Envelope Energy Requirement for Climate Neutrality. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 202, 114712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.114712

Dafflon, B., Moalla, N., and Ouzrout, Y. (2021). The Challenges, Approaches, and Used Techniques of CPS for Manufacturing in Industry 4.0: A Literature Review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 113(7–8), 2395–2412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-06572-4

El-Haouzi, H. B., Valette, E., Krings, B.-J., and Moniz, A. B. (2021). Social Dimensions in CPS and Iot Based Automated Production Systems. Societies, 11(3), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030098

Fakhr Ghasemi, A., and Pinto Duarte, J. (2025). A Systematic Review of Innovative Advances in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Implications for Architecture and Construction. Materials, 18(8), 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18081820

Fatima, Z., Tanveer, M. H., Waseemullah, Zardari, S., Naz, L. F., Khadim, H., Ahmed, N., and Tahir, M. (2022). Production Plant and Warehouse Automation with Iot and Industry 5.0. Applied Sciences, 12(4), 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12042053

Ghasemi, A. F., and Duarte, J. P. (2025). A Systematic Review of Innovative Advances in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Implications for Architecture and Construction. Materials, 18(8), 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18081820

Golchha, R., Khobragade, P., and Talekar, A. (2024). Design of an Efficient Model for Health Status Prediction Using LSTM, Transformer, and Bayesian Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovations and Challenges in Emerging Technologies (ICICET) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICET59348.2024.10616353

Grigoriadis, K. (2022). Computational and Conceptual Blends: Material Considerations and Agency in a Multi-Material Design Workflow. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 11(3), 618–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2022.04.005

Hassan, M., Mohanty, A. K., and Misra, M. (2024). 3D Printing in Upcycling Plastic and Biomass Waste to Sustainable Polymer Blends and Composites: A Review. Materials and Design, 237, 112558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112558

Jamwal, A., Agrawal, R., Sharma, M., and Giallanza, A. (2021). Industry 4.0 Technologies for Manufacturing Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Applied Sciences, 11(12), 5725. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11125725

Kantaros, A., and Ganetsos, T. (2024). Integration of Cyber-Physical Systems, Digital Twins and 3D Printing in Advanced Manufacturing: A Synergistic Approach. American Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 17, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajeassp.2024.1.22

Lievano-Martínez, F. A., Fernández-Ledesma, J. D., Burgos, D., Branch-Bedoya, J. W., and Jimenez-Builes, J. A. (2022). Intelligent Process Automation: An Application in Manufacturing Industry. Sustainability, 14(14), 8804. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148804

Mostafavi, S., Kemper, B. N., and Du, C. (2019). Materializing Hybridity in Architecture: Design to Robotic Production of Multi-Materiality in Multiple Scales. Architectural Science Review, 62(5), 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.2019.1653819

Pajonk, A., Prieto, A., Blum, U., and Knaack, U. (2022). Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing in Architecture and Construction: A Review. Journal of Building Engineering, 45, 103603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103603

Shaukat, U., Rossegger, E., and Schlögl, S. (2022). A Review of Multi-Material 3D Printing of Functional Materials Via Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers, 14(12), 2449. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122449

Verma, A., Kapil, A., Klobčar, D., and Sharma, A. (2023). A Review on Multiplicity in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Process, Capability, Scale, and Structure. Materials, 16(15), 5246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16155246

Zhao, X., Boruah, B., Chin, K. F., Đokić, M., Modak, J. M., and Soo, H. S. (2022). Upcycling to Sustainably Reuse Plastics. Advanced Materials, 34(15), 2100843. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202100843

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.