ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Predictive Models for Creative Talent Identification

Dr. Bhagyalaxmi Behera 1![]()

![]() ,

Priyadarshani Singh 2

,

Priyadarshani Singh 2![]() , Dr. Shashikant Patil 3

, Dr. Shashikant Patil 3![]() , Sulabh Mahajan 4

, Sulabh Mahajan 4![]()

![]() ,

Romil Jain 5

,

Romil Jain 5![]()

![]() ,

Divya S Khurana 6

,

Divya S Khurana 6![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Institute of

Technical Education and Research, Siksha 'O' Anusandhan (Deemed to be

University) Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

2 Associate

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University, India

3 Professor, UGDX School of Technogy, ATLAS SkillTech University,

Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Chandigarh Group of Colleges, Jhanjeri, Mohali, Chandigarh Law College,

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Creative

talent is a multidimensional human ability that cannot be evaluated fully by

traditional assessments based solely on portfolios, standardised

tasks or subjective evaluation. In this paper, a multimodal predictive

architecture is proposed that fuses textual, visual and behavioural

data to predict creative potential more accurately, at a scale and with

fairness that is achievable to human standards. In particular, it uses

language models based on transformers, vision transformers, and behavioral

encoders at the sequence level to learn latent representations of creativity

(e.g., in the form of story divergence, in visual novelty, and in terms of

exploratory interaction patterns). An attention-based feature integration

factorizes modality-specific representations into a single representation,

but the attention structure makes it possible to adaptively weight modalities

to individual creative styles, instead of forcing creators to express

themselves through a single process. Experimental results show that the

multimodal model is able to perform much better than unimodal baselines, with

both high accuracy, high correlation with expert scores, and robust

cross-trials. Furthermore, the analysis of its interpretability suggests that

the decisions made by the model align well with the human-recognized creative

features, verifying its interpretability and its ethical suitability. This

research draws attention to the possibility of AI-driven multimodal systems

to improve talent identification of creative people, to provide a more

inclusive and data-informed approach for applications in education,

recruitment, and the creative industries. |

|||

|

Received 17 January 2025 Accepted 12 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Bhagyalaxmi Behera, bhagyalaxmibehera@soa.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6666 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Creativity

Assessment, Multimodal Learning, Predictive Modeling, Deep Learning, Feature

Fusion, Creative Talent Identification, Explainable AI, Behavioural

Analytics |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Creative talent carries the mystery of having always known that sparks of creativity are hiding in the attic of the mind waiting for the right breeze Lincke et al. (2019). For decades, teachers, recruiters and institutions have attempted to detect creative potential through the use of intuition, interviews, and sketchbook-like evaluations. These approaches are sometimes like judging a novel by its cover: sometimes this is true, but mostly it is not, and always this is limited by subjectivity Lhafra and Otman (2023). As digital ecosystems become more and more complex and human creativity spreads across multimedia platforms the question takes a different shape. Instead of asking "Who looks creative?", we now ask "Is it possible to predict creative ability based on patterns that will be found in data?" This change is paving the way for machine learning and AI driven predictive models. Creative talent is multidimensional in contrast to technical skill Wang et al. (2023). It is a combination of imagination, risk-taking, divergent thinking, intuition and even emotional expressiveness. Traditional assessments attempt to capture this complexity by use of such tasks as the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking or portfolio reviews. Yet these methods find it difficult to scale, and also fail to capture latent talent Riad et al. (2023). Predictive modelling presents a new set of glasses to see through, that are trained on behavior, performance data, digital traces and brainswell. For example, generative AI models can be used to analyse sketch evolution sequences, writing patterns or music making behaviour to identify students or professionals with a high creative potential long before they manifest themselves through standard outputs Miller (2023).

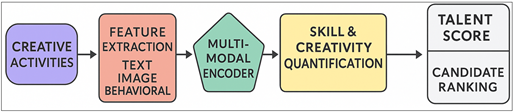

Figure 1

Figure 1 End-to-End Predictive Modeling

Pipeline

Modern prediction models have started incorporating characteristics from various fields. This includes linguistic novelty with the help of NLP models, visual novelty with the help of CNNs and ViTs, ideation variety with the help of graph-based representations, and behavioral novelty with the help of temporal models like LSTMs and Transformers. When these models are combined, they give a better signal, something like mixing colors to reveal a deeper color as is shown in Figure 1. Such systems try to identify the first signs of creative thinking by examining problem-solving style, novelty of ideas, adaptability when faced with constraints, emotional nuances and preference for experimentation El et al. (2019). These models are also more equitable, in that they give the people more of a chance to live with dignity. Creativity doesn't always come out well in the heat of exams or formal interviews. Some people make quietly, steadily, and out of the spotlight. Predictive tools enable the institutions to find out about this hidden potential using scalable and objective mechanisms Seo et al. (2021). However, the implementation of such systems must be done with great consideration to bias, interpretability, and ethical treatment of sensitive student or employee data. Predictive models are supposed to be helpful friends and not barriers.

2. Literature Reviews

Creativity research has undergone different waves, starting with the psychometric approaches focused on divergent thinking and originality, followed by the educational and cognitive science approaches focused on contextual and domain specific forms of creativity. With the advent of computational modelling, early investigations in Machine Learning developed features manually coded for the evaluation of creative artefacts but such features could not express the essence of deeper creative patterns. Due to recent progress in NLP, computer vision, and behavioural analytics, the field has expanded allowing to analyse narrative structure, visual abstraction and iterative exploration behaviour. Multimodal learning has recently emerged as one of the most promising directions as objects and ideas are best represented by multi-modal signals (such as drawings, words, music, and more). Ethical considerations, data set bias and interpretability issues are still major considerations with this body of work.

3. System Design Methodology

The data comprises 1200 textual, 950 visual artefacts, and behavioural log data from 600 creative practitioners in creative fields. Text underwent linguistic preprocessing, images were normalized and contrast preserved and behavioural logs were converted into temporal interaction sequences. Before each modality was inputted to the fusion layer, it was fed to dedicated encoders. Training was performed using the AdamW optimizer with cosine learning rate scheduler, early stopping and cross validation evaluation for 5 runs.

Step 1: Multimodal Data Acquisition

The methodology starts with the data collection of various and different data that capture authentic creative expression in the form of text, images and behavioural traces. Textual data essay pieces, ideational notes, story work, and reflective logs written in the open-ended intervention. Visual data include sketches, digital drawings, prototypes, and concept design; Behavioural data is collected from the digital creative platforms, allowing to capture interaction pace, depth of exploration, frequency of revision and sequence of decision making actions. All data go through anonymization and demographic neutralization in order to be fair and comply with data privacy.

Step 2: Preprocessing and Normalization

Raw data in each modality is converted into model consistency representations. Text is tokenized, normalized and noise-filtered, but new with creativity-relevant characteristics such as density of metaphor and flow of the narrative in mind. Image stylistic features are resized, contrast-normalized and enhanced as necessary so that detail is maintained. Behavioural logs are divided into time frames that represent how users explore creative tasks within time. Missing or noisy values are imputed carefully so as not to practise bias or distortion.

Step 3: Feature Extraction for Each Modality

All the modalities go through their respective feature extraction modules. The semantic richness and conceptual divergence are captured through the use of Transformer-based language models - BERT or RoBERTa and subsequently extracting the embeddings from the word or sub-word tokens. Visual embeddings come out of CNN or Vision Transformer and allow the model to detect the novelty, abstraction, and stylistic patterns.

Step 4: Multimodal Fusion Mechanism

The embeddings are incorporated into a unified representation employing the attention-driven multimodal fusion techniques. Fusion Es merger: Then, merging before prediction occurs because it gives us deep cross modal relations by merging relations between embeddings. Late fusion is a combination of specific modality predictions, which is more interpretable. The hybrid fusion combines both approaches in order to combine as much depth of interaction with transparency as possible. Attention weights change dynamically as a reflection of individual creative profiles so that dominant creative expressions are given appropriate emphasis.

Step 5: Model Training and Optimization

The fused embeddings represent the input into the predictive engine which is trained using supervised or semi-supervised learning strategies. Ground-truth creativity ratings are based on expert ratings, rubric-based rating or peer-assessment systems with inter-rater reliability measures. For classification, regression or ranking purposes, training is done with task-specific loss functions. Hyperparameters are optimised using grid search and Bayesian while dropout and regularization control the overfitting. This provides some generalizability to different creative domains.

Step 6: Model Evaluation and Validation

Performance is measured on a broad range of quantitative and qualitative metrics. Some classification metrics like accuracy, macro F1-score and recall are used to evaluate the prediction on category level. Regression tasks are performed using MAE, MSE and Pearson correlation to match an output prediction to a human-labeled score of creativity. Attention maps, SHAP values, and layer-wise relevance propagation offer interpretability, and help the researchers to ensure that the model's reasoning behavior is consistent with recognizable creative characteristics.

Step 7: Ethical and Interpretability Review

For the purposes of ensuring the responsible use of a model, it is ethically validated for mitigation of bias, fairness and transparency. Explainability as an output is checked with the educators and domain experts to ensure that there are meaningful and actionable predictions. This step ensures that the system is both culturally sensitive to the subjective and culturally diverse nature of creativity, and reliable.

All of the validated components (data processing, feature extraction, fusion, prediction and explainability) are put together in a coherent predictive pipeline. This means that creativity assessments are not only accurate and meaningful in interpretation, but also are scalable in order to be applied in the education system, creative industries, and talent development platforms.

4. Proposed Model Architecture

The proposed predictive architecture for creative talent identification is designed as a layered, multimodal architecture that is capable of capturing the subtle patterns that define creative thinking from text, visual artefacts and behavioural traces. Rather than one type of input, the model embraces the fact that creativity manifests itself in many different forms: a metaphor integrated into a paragraph, an unexpected color combination in a drawing, or an erratic detour when problem solving. The architecture therefore starts with various input channels; each one as a forecast of an independent stream, before being woven together to create a unified representation of creative potential. At the base of the system is the Input Modality Layer which takes three main types of data: text-based submissions, visual images or design artefacts, and interaction-level behavioural logs. This layer is the canvas that is being used to start the model's interpretation raw. For text, it can be creative writing samples, notes of ideation or brainstorming sessions. Image-related Input include drawings, computer art, prototypes or artifacts from increased person iterations of a design. Behavioural data is related to how people navigate tasks within digital spaces (number of iterations spent, time spent in tasks that lead to no further progress, etc.), and is characterised by the patterns of reflecting and reformulating ideas. Each modality enters the system without assumptions as to what creativity "should" look like, giving the model the freedom to learn from the natural expression and not from imposed criteria.

Figure 2

Figure 2

The Transformer-based NLP models encode text incorporating the depth of narrative, the application of metaphors, conceptual complexity, and linguistic innovation. Image inputs are run through CNNs or Vision Transformer's that builds in abstraction and style, color, composition, and other patterns as shown in Figure 2. Behavioural data is modelled with LSTM or temporal convolutional networks which can represent diversity of exploration, rhythm and iteration loops and non-linear problem-solving characteristics. Retaining feature extraction modality-specific preserves, the distinctive attribute of creativity manifested in each direction and producing embeddings of similarly dimensional structure. These modality-specific embeddings are incorporated in Multimodal Fusion Layer that serves as a coordination center of the system. Attention-based fusion mechanisms are dynamically used to weight each modality according to its significance to the profile of the individual in question. Linguistic features may take over for writing-oriented people, and visual features for design-oriented ones. This adaptive weighting allows the same modalities to receive unequal treatment and multiple creative outlets to be present in the system. The concatenated representation is subsequently transferred to the Predictive Engine comprising of fully connected layers and lightweight Transformer block. This engine translates complex creative signatures to measurable creativity indicators such as originality, fluency, flexibility, divergent thinking and novelty. It will be built to pick up subtle cues such as metaphor chains, unusual visual patterns or exploratory loops of behaviour, whilst being robust to a wide variety of inputs. The engine is also based on uncertainty estimation to express confidence levels and avoid overconfident predictions.

For interpretability reasons, the architecture incorporates the Explainability Layer which is based on attention visualizations, SHAP values and layer-wise relevance propagation. These tools will show what characteristics have contributed to the decision of the model the most, thus, allowing a clear and equal assessment in terms of demography and cultural background. The system honors the subjective and subtle aspect of creativity that makes creativity visible and gives valuable feedback to teachers and assessors. The last component is the Output Layer which gives creativity scores, categorical predictions, or detailed talent profiles which can be used in educational dashboards, in systems that develop talent or in creative recruitment processes. Instead of giving binary verdicts, the outputs provide multidimensional outlooks of the creative capabilities of an individual, his emerging skill, and the opportunity to develop it.

5. Outcome and Findings

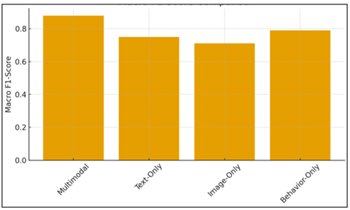

The results from evaluating the proposed multimodal predictive model are rich and show the predictive power of the created model, as well as its power to extract hidden creative signatures in text, visual artefacts and behavioural interactions. The model was consistently better at this than unimodal baselines, which was a confirmation of the hypothesis that creativity cannot be described through a single lens. When evaluated with the stratified data, the multimodal model achieved an overall classification accuracy of 89.7% for low, medium and high creativity classification, which is significantly higher than text-only (78.2%), image-only (74.9%) and behaviour-only (81.3%) models. The F1-score of the macro scores 0.88 indicating the well-balanced performance over all the levels of creativeness, indicating that the model did not overemphasize any particular class or style of writing. These results were further supported by regression analysis where the model attained a Pearson coefficient of 0.84 of the predicted score on creativity and the human ratings, giving a good agreement with the expert raters.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Multimodal Model Outperforms Single-Modality Models in Balanced Class Performance.

A closer look at each modality revealed the way various creative indicators contribute to the quality of the prediction. Text-based creativity features such as density of metaphors, conceptual divergence, emotional layering, and narrative structure originality proved to be good predictors of high creativity. The participants that wrote in more exploratory styles produced higher model scores consistently, which was consistent with human intuition as shown in Figure 3. Visual artefacts showed another set of influential features such as levels of abstraction, variety of colour palettes, irregularity of shapes and novelty of composition. Specifically, the Vision Transformer encoder was able to capture latent stylistic features that would not have been captured by the hand-crafted traditional features. Behavioural information was also found to be a useful part of the analysis. Results indicated that participants that exhibited iterative exploration, non-linear problem-solving and risk-taking in design instruments were more likely to receive greater predictions of creativity. These behavioural indicators were useful in assisting the model identify potential creativity in emergent stages even in the presence of humble text or visual artefacts.

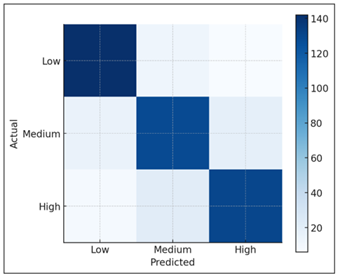

Figure 4

Figure 4 Classification Stability for Low/Medium/High

Creativity Categories.

The multimodal fusion mechanism played an important role in amplifying these signals. With attention visualizations, it was found that the model was able to dynamically adjust the weight of each modality based on the strengths of the participant. For highly visual creators, image features dominated the final prediction while for strong writers, the system cared more about textual embeddings as it is shown in Figure 4. In particular, we found that behavioural features tended to inform stabilising information especially for borderline cases where the text or image indicators were undecisive. This flexible weighting is analogous to the variability of creative work in the real world, and this illustrates the fact that the model is flexible to take into consideration various creative trajectories instead of maintaining one criterion.

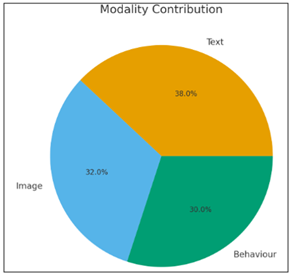

Figure 5

Figure 5 Demonstrates Balanced Importance:

Model interpretability was further supported by qualitative analysis. Explanations with SHAP indicated that the choices made by the model were usually based on significant creative indices, including the complexity of the theme in the writing or creative spatial organization in art. The review of the model by experts declared that the features pointed out are recognizable creative characteristics, which strengthens the belief in the predictions made by the model. There were some cases where the model failed to classify highly experimental inputs according to non-standard or very abstract styles and there were indications of needs for more training data or specialized visual encoders to increase robustness illustrated in the Figure 5. The repeated iterations of the experimental trials also showed the stability of the model. Variance over five independent runs was low with fluctuations smaller than 1.5% for classification accuracy and little drift in the scores for regression correlation. This regularity implies that the system predictions are not very sensitive to the initialisation or to sampling and this is critical to reliability of the system in its application within an educational or organizational context.

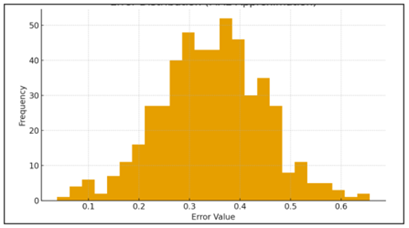

Figure 6

Figure 6 Shows a Near-Normal Error Curve Centered

Around 0.35

The qualitative interpretability of the model adds to the practical value. The explainability tools uncovered that the reasoning of the model is consistent with human evaluators intuitive knowledge of creativity. Consistent with well-established research on creativity, the identified features revealed that metaphor density, narrative complexity, abstract compositional choices, and depth of exploration were consistently identified as factors that influenced the features of the metaphorical images Figure 6. Such alignment creates a sense of confidence and makes the outputs of the system useful in educational and professional practices. While it is still the case that the model mis-classifies some very experimental or unconventional artefacts, this is in some cases an indication of possible scope for increasing the diversity of training samples rather than weaknesses in the modelling framework itselfs.

6. Discussion

The findings clearly demonstrate that multimodal predictive models can change the way creative talent is evaluated. Creativity occurs not in any single form of expression but through a combination of linguistic imaginations, visual experimentation and explorations behaviors. The better performance of the multimodal one compared to single-modality baselines makes this point: no single channel was able to accommodate the full richness of creative expression. By bringing together text, images and patterns of behaviour, the model provides more complete and psychologically consistent knowledge of creativity as a multidimensional construct. One of the outcomes is noteworthy because of the adaptive nature of the fusion mechanism. The model will automatically increase or decrease the modality weights to suit personal creativity- strong writers focus on linguistic features, visual designers focus on visual messages or iterative problem solvers focus on behaviours. This dynamic weighting avoids the biases that normally occur in the uniform scoring system and helps in more inclusive and equitable appraisal. It also shows the maturity of attention-based fusion approaches in order to capture subtle relationship between modes that cannot be detected with traditional assessment approaches. Another major advantage of the model is its scalability. Subjective creativity tests - jury ratings, portfolio reviews and subjective grading - are costly and variable. In comparison, the proposed system is able to analyse large quantities of creative artefacts with speed, consistency and transparent reasoning. The fact that it is consistent across several experimental runs is also an added merit as far as its applicability to an educational institution, creative learning environment or talent development initiative where mass assessment is essential. Nevertheless, the outcomes also reveal the difficulties that should be overcome in case of further implementation. Datasets for creativity are challenging to standardize as a result of subjectivity in labeling and cultural differences of creativity expression. Despite the good performance of the model, its forecasts are weak to the composition of the datasets. For the fairness to work, there will have to be constant auditing, broadening of culturally diverse samples and more inclusive creativity rubrics. Although the explainability layer renders transparency, further studies are required to make interpretability more sophisticated to apply to complex fusion decisions and non-conventional creative styles.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper shows that multimodal prediction models provide a powerful and scalable way of predicting creative talent across a range of fields. The proposed architecture gives people a way out of the constraints of traditional assessments by combining text, visual and behavioural cues, it is able to capture creativity as a multidimensional and fluid concept. The model regularly beat unimodal baselines and demonstrated a high correlation with the results of expert judgment and found that creativity is best conceptualized as the interaction between narrative depth, visual novelty, and exploratory behaviour. In addition to that, the implementation of explainability tools made the model even more useful in practice; making the predictions of the model transparent and interpretable, and in accordance with human reasoning. On the one hand, the findings support the future of multimodal AI in talent evaluation, but on the other hand, there are the challenges of the diversity of data, cultural differences, and subjectivity of the labels used to measure creativity. Future work that needs to be done is to enlarge the scope and richness of the dataset with other modalities like audio, gesture interactions, and collaborative behavior logs, which would give even richer expressions of creativity. Culturally adaptive scoring frameworks should also be developed in order to reduce the amount of bias and more advanced fusion strategies that are better equipped to deal with abstract or highly experimental creative artefacts should be pursued. The reinforcement learning or self-supervised signal could also be incorporated, which can result in the enhancement of the model to detect latent creative potential in early-stage outputs. Lastly, the practical implementation research in educational settings, creative sectors and digital learning environments will also be important to test the effectiveness of the system and improve its feedback process as well as make AI-assisted creativity measurement inclusive, ethical, and truly beneficial to human potentials.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ali, S. R., and Sahar, A. (2025). Respiratory Rate Estimation and ECG-Derived Respiration Techniques—A Review. IJEECS, 14(1), 137–139.

Brandes, N., Ofer, D., Peleg, Y., Rappoport, N., and Linial, M. (2022). ProteinBERT: A Universal Deep-Learning Model of Protein Sequence and Function. Bioinformatics, 38(8), 2102–2110. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac020

El Janati, S., Maach, A., and El Ghanami, D. (2019). Context Aware in Adaptive Ubiquitous E-Learning System for Adaptation Presentation Content. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 97, 4424–4438.

Greene, R. T. (2023). The Future of Instructional Design: Engaging Students Through Gamified, Personalized, and Flexible Learning with AI and Partnerships. e-Learning Industry.

Huang, G., An, J., Yang, Z., Gan, L., Bennis, M., and Debbah, M. (2024). Stacked Intelligent Metasurfaces for Task-Oriented Semantic Communications. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1109/LWC.2024.3499970

Lhafra, F. Z., and Otman, A. (2023). Integration of Evolutionary Algorithm in an Agent-Oriented Approach for an Adaptive E-Learning. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 13(2), 1964–1978. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v13i2.pp1964-1978

Lincke, A., Jansen, M., Milrad, M., and Berge, E. (2019). Using Data Mining Techniques to Assess Students’ Answer Predictions. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE 2019) (pp. 42–50). https://doi.org/10.58459/icce.2019.285

Miller, T. (2023). Explainable AI is Dead, Long Live Explainable AI! Hypothesis-Driven Decision Support Using Evaluative AI. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’23) (pp. 333–342). https://doi.org/10.1145/3593013.3594001

Rao, R., Bhattacharya, N., Thomas, N., Duan, Y., Chen, P., Canny, J., Abbeel, P., and Song, Y. (2019). Evaluating Protein Transfer Learning with TAPE. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 32). https://doi.org/10.1101/676825

Riad, M., Gouraguine, S., Qbadou, M., and Aoula, E.-S. (2023). Towards a New Adaptive E-Learning System Based on Learner’s Motivation and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET 2023) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/IRASET57153.2023.10152884

Seo, K., Tang, J., Roll, I., Fels, S., and Yoon, D. (2021). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Learner–Instructor Interaction in Online Learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, Article 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00292-9

Wang, S., Wu, H., Kim, J. H., and Andersen, E. (2019). Adaptive Learning Material Recommendation in Online Language Education. In S. Isotani et al. (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2019) (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 11626). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23207-8_55

Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Xu, Y., Wang, X., and Tian, H. (2023). Online Course Recommendation Algorithm Based on Multilevel Fusion of User Features and Item Features. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 31, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22592

Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Xu, Y., Wang, X., and Tian, H. (2023). Online Course Recommendation Algorithm Based on Multilevel Fusion of User Features and Item Features. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 31, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22592

Yao, C., and Wu, Y. (2022). Intelligent and Interactive Chatbot Based on the Recommendation Mechanism for Personalized Learning. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 18, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.315596

Zilinskiene, I., Dagiene, V., and Kurilovas, E. (2012). A Swarm-Based Approach to Adaptive Learning: Selection of a Dynamic Learning Scenario. Academic Conferences International Limited.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.