ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Folk Art Digitization Management Framework

Dr. Talisenla Imsong 1![]() , Dr. J. Karthikeyan 2

, Dr. J. Karthikeyan 2![]() , Dr. R. Vasanthan 3

, Dr. R. Vasanthan 3![]() , Dr. Peeyush Kumar

Gupta 4

, Dr. Peeyush Kumar

Gupta 4![]()

![]() , Dr. Khriereizhünuo Dzüvichü 5

, Dr. Khriereizhünuo Dzüvichü 5![]() , Yuvraj Parmar 6

, Yuvraj Parmar 6![]()

![]() , Dr. Kumud Saxena 7

, Dr. Kumud Saxena 7![]()

![]()

1 Associate

Professor, Department of English, Nagaland University (Central). Kohima Campus,

Meriema, Nagaland, India

2 Ph.D.,

Assistant Professor Head, Career Guidance and Placement Cell, National College (Autonomous),

Tiruchirappalli Tamilnadu, India

3

Associate Professor, Department of English

Nagaland University Kohima Campus, Meriema Kohima, Nagaland, India

4 Assistant Professor, ISDI - School of

Design and Innovation, ATLAS SkillTech University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of

History Central University of Tamil Nadu, Tamil Nadu, India

6 Chitkara Centre for Research and

Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

7 Professor, Department of Computer

Science and Engineering, Noida Institute of Engineering and Technology, Greater

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Folk art has

to be preserved and disseminated in a digital age within a cultural

framework, with the proper use of technology and enduring nature. The Folk

Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) is a model which is proposed in

this study. It is designed to assist in digitising, managing and sharing

traditional arts. The approach is founded on ideas of different fields,

combining observational study, archive practices and digital preservation

methods. It emphasizes the need to work collectively with artists, groups and

cultural institutions to ensure that the digitisation process is real and

open to all. The research combines a combination of surveys, historical

content and interviews with stakeholders to determine the various methods of

digitisation of folk art and the challenges involved. FADMF consists of three

major components: (1) Conceptual Model, which is used to describe metadata

standards and content organisation; (2) Workflow Design, used to design how

to acquire, catalogue, store, and access content; and (3) Stakeholder Roles,

which describes the roles of policymakers, technologists, and people that

care about culture. A test application demonstrates the ways in which the

framework can be applied and compares the success of the framework to that of

other digital heritage models. He found that the information is more valid,

easier to access, and more socially acceptable. The paper also discusses

infrastructure requirements, data management, and policy implications that

will contribute to digital preservation for future stability. |

|||

|

Received 17 January

2025 Accepted 10 April

2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Talisenla Imsong, talisenla@nagalanduniversity.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6649 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Folk Art Digitization, Cultural Heritage Management,

Digital Preservation Framework, Metadata and Archival Systems, Ethical

Digitization Practices |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Folk art reflects the creative, culturally aware and historically linked nature of a community over time. Paintings, crafts, statues, music and shows are among other forms of art that have strong roots in the local customs, routines and social practices. But due to the rapid change of times, due to people moving to cities, and the loss of traditional skills, these valuable cultural objects are disappearing over time. Problems of preservation, accessibility and sustainability are facing those who embody the guardians of our culture. Digitising folk art is becoming clear as an important way of protecting and reviving these practices for future generations. More importantly, when it comes to cultural property, digitisation is more than converting physical objects to digital ones Van Nuenen and Scarles (2021). It also involves the planned management of data, metadata and background information to ensure that the digital objects are authentic and understandable and usable. Folk art creates a particular challenge in this area, since its styles tend to be non-standardised, transmitted orally from community to community and are not rule-based. This requires frameworks that are sensitive to culture and flexible from a technical perspective. While folk cultural traditions are community-based, changing over time, the digital archiving models that were developed primarily for museums, libraries and archives don't necessarily suit them well Kontopanagou et al. (2024). So, there is an urgent need for a domain-specific model which not only digitises folk art but also takes care of and protects its intangible core.

The Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) helps to fill-in this gap by offering a comprehensive and scalable framework to include study methods, technical tools and community-based activities. It is intended to develop an environment that allows lawmakers, researchers, cultural workers, and artists together to digitally archive, collect, and share folk art Thomas and Douglas (2024). The main goals of the framework are to (a) establish standard procedures for collecting and managing metadata for folk art materials, (b) establish efficient workflows for storage, retrieval, and access, and (c) establish stakeholder roles to ensure that the community is involved and that the materials are represented fairly. Figure 1 illustrates the main elements, process, and governance of digitization of folk art. The research is conducted using mixed-method approach to support FADMF. This involves qualitative fieldwork, archive study and digital technology analysis. While on-site fieldwork allows live recording of traditions and the stories of artisans, archival research enables placing historical information in digital archives Pratisto et al. (2022).

Figure 1

Figure 1 Structural Overview of the Folk Art Digitization

Management Framework

Tracings and documentation: Use of digital technology such as high resolution images, 3D scanning and information labelling systems also ensures that the work is accurate, and that the work can be shared with other cultural property libraries. FADMF advocates for collaborative practices of digitisation where technological innovation is accompanied by cultural ethics Innocente et al. (2023). This provides communities with the power to be co-creators rather than passive subjects. This ensures that the cultural background, meaning and live aspects of the art forms can be seen in digital records.

2. Related Work

In the past twenty years, there have been significant changes in the field of digitisation of cultural property. This is due to the increasing demand to use digital technologies to safeguard both material and immaterial cultural resources. A number of systems and projects are put in place to standardize digital storage, information control and accessibility to the material. However, most of the models were developed for museum, library, and records collections as opposed to folk art forms that occur in communities. Europeana, UNESCO's Memory of the World and the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) were among the pioneers in the integration of various cultural material into a single digital setting Maietti (2023). These systems promote information exchange based on Dublin Core, CIDOC-CRM and OAI-PMH standards. This way data can be shared between institutions and individuals worldwide. In the same way, projects such as the Smithsonian's Global Sound Project, and the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) digital libraries, have made it clear how important it is that communities get involved and record oral and performance-based traditions in their original settings. Folk art is localized, dynamic, and collective; however, the current models tend to be less sensitive to these concerns Okanovic et al. (2022). Models like the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) and Digital Curation Centre (DCC) lifecycle models offer organised ways to keep data safe, but they don't have ways to adapt to changing cultural stories and community control. There are not many management models that incorporate research data, information standards, and ethical digitisation practices. Although research in indigenous digitisation and community libraries emphasizes the importance of co-creation, this is not the case in this study. New research in digital humanities and historical informatics support mixed systems that are technically sound and are sensitive to different cultures. It is evident from these studies that there is a need for flexible models that find a balance between sincerity, ease and sustainability. Table 1 summarizes some of the main projects, techniques, advantages and social aspects Marino et al. (2022). The Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) develops on the basis of these earlier undertakings by placing them in a folk art context. The framework addresses the gap between the institutional standards for digital preservation and the community-based knowledge systems.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work in Folk Art and Cultural Heritage Digitization |

|||||

|

Focus Area |

Methodology |

Metadata Standard Used |

Key Features |

Benefits |

Impact |

|

Cultural Heritage

Aggregation |

Digital archives, open APIs |

Dublin Core, EDM |

Pan-European digital library |

Interoperability,

multilingual access |

Enhanced cultural exchange

and cross-border visibility |

|

Documentary Heritage Schuhbauer et al. (2022) |

Archival digitization, conservation |

Custom UNESCO metadata |

Safeguarding endangered records |

Global recognition and conservation funding |

Preservation of rare manuscripts and folk documents |

|

Open Access Cultural

Collections Puig et al. (2020) |

Linked data integration |

Dublin Core, JSON-LD |

Unified national metadata

schema |

Centralized access to U.S.

heritage |

Strengthened research and

education access |

|

Intangible Cultural Heritage (Music, Oral Art) |

Field recording, audio archiving |

MARC, Dublin Core |

Sound-based ethnographic archives |

Preservation of oral folk traditions |

Promoted global awareness of indigenous sound heritage |

|

Cultural Site Documentation Ercan (2020) |

3D scanning, GIS mapping |

CIDOC-CRM |

Archaeological and folk

heritage digitization |

Integration of tech and

culture |

Preservation of tangible and

intangible Indian heritage |

|

Community-Based Heritage |

Participatory documentation |

ICH metadata schema |

Community-driven heritage records |

Empowerment of traditional custodians |

Recognition of living heritage globally |

|

Audiovisual Heritage Bortolotto (2021) |

Sound digitization, open

data |

EDM, Dublin Core |

Collaborative audio archives |

Broader audience access to

sound culture |

Reinforced intangible

cultural identity |

|

Data Lifecycle Management |

Curation workflow tools |

DCC lifecycle model |

Structured digital stewardship |

Standardized preservation practice |

Academic integration in heritage digitization |

|

Multi-domain Knowledge

Repository Corallo et al. (2021) |

Metadata aggregation, AI

search |

Dublin Core |

Nationwide digital library |

Resource accessibility and

inclusivity |

Democratized learning and

heritage education |

|

Art Digitization and Visualization |

360° imaging, storytelling |

Proprietary schema |

Immersive virtual exhibitions |

Public engagement and visualization |

Global exposure to traditional art forms |

3. Methodology

1) Research

Design and Approach

The research is a mixed-method and experimental design, which means qualitative and quantitative methods are used to develop and test the Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF). The study was designed according to an interpretivist model, which emphasizes the significance of culture, community, and observation. Folk art is dynamic and is shaped by the context; as a result the design is a blend of ethnographic fieldwork, case study analysis and technology evaluation with a focus on highlighting the physical and spiritual components of folk art Skublewska et al. (2022). There are three sections of the study. In the first step, a large amount of literature is read and existing models of digital heritage are examined in order to find gaps which are relevant to the preservation of folk art. The second stage is about participation in the field. This means taking the time to look at and interview artisans about what they do, how they interact with other people in the community, and how ideas are locally transmitted. In the third stage, framework construction, scientific, cultural and social dimensions are put together to produce a working model Chong et al. (2021). This design ensures that FADMF is not only a theory, but a useful, flexible framework that has been put to the test. The model can be improved and changed to meet the needs of the community and new technologies by continuously designing, testing and improving the model. Triangulation of data sources, or basically cross-referencing observations made in the field, records kept in archives, and studies of digital infrastructure, also contribute to validity and dependability. In the end, the study plan is the integration of the digital management system and cultural record. This ensures that the framework is as scientifically valid as possible and sensitive to various cultures. It likewise provides a long-term answer to digitizing folk art.

2) Data

Collection Techniques (Fieldwork, Archives, Interviews)

In order to reflect the variety and complexity of the folk art forms, data for FADMF are gathered by both qualitative and quantitative research. The primary means is fieldwork, which allows you to work directly with artists, culture practitioners, and groups. The research traces artistic processes and the use of materials, their symbolic meanings and routines in the community through participant observation, the use of photos and audiovisual recording. These observations reveal the live context of folk art which is important for creating meaningful digital representations. Apart from investigation, the research of archives provides us with historiographical data about the past Jadhav (2025). Manuscripts, museum catalogues, directories, and government files are examples of the types of records that are examined in order to determine the evolution of art forms, as well as changes in recording standards over time. In addition to establishing legitimacy and validating bloodline, archival data helps in the creation of information and links both traditional and digital records. The third major source of data is from semi-structured interviews and focus group meetings which provide an opportunity for people to discuss their experiences, issues and hopes for digitisation. Created by artists, designers, technologists, and policymakers, the frameworks all represent the perspectives of the creators. The discussions are transcribed, coded and analysed thematically in order to identify patterns of individual participation in the community, their concerns about ethics and their desires for security.

3) Tools

and Technologies for Digitization

Folk art must be digitized with cutting-edge digital solutions, information protocols, and preservation technologies that ensure the art is well preserved and easily available to many over the long term. The FADMF has both hardware and software components used to process all of the steps involved in digitisation, such as acquisition and archiving of the data. High resolution digital cameras, 3D scanners and hand-held audio-visual recording devices are used to capture visual, literary and performance art. These devices preserve the original shapes and support different file formats (JPEG2000, TIFF, MP4, OBJ) which can be used for archive purposes. Photogrammetry and laser scanning are non-invasive methods of making digital copies of artefacts which are fragile or can't be moved. The framework uses content management systems such as Omeka, DSpace or CollectiveAccess to manage data. These systems are used in combination with information standards such as Dublin Core, CIDOC-CRM and VRA Core in order to maintain data consistency and interoperability. Multilingual knowledge areas and controlled languages make it possible to cross cultures and connect things in context. Information storage and retrieval technologies including cloud-based storage technologies, digital stores, and open access platforms that ensure file safety and that users can engage with the information; For long term maintenance with OAIS compliant protocols, software for digital preservation such as Preservica or Archivematica is built in.

4. Folk Art Digitization Management Framework (FADMF)

1) Conceptual

Model and Core Components

The Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) is intended to be a full one that integrates precise technology and cultural accuracy. This plan will be used to assist in the systematized digitization, management and distribution of the physical and nonphysical forms of folk art. The concept framework is rounded around three key and interdependent components: content, process, and governance. Content Component comprises all the elements that can be displayed on folk art practices, such as artefacts, events, oral histories and visual representations. It is the basis of validity, applicable recording and information expansion and is aimed at preserving the physical and cultural core of the work. The Process Component outlines the working elements that are responsible for digitisation tasks. This involves processes for acquiring, cataloguing, digitally preserving and providing access to objects. Each step should be in compliance with international rules, but should at the same time be flexible enough to adapt itself to local cultural circumstances. This section defines how stakeholders can communicate with one another and what data they are allowed to work with. It achieves this by setting policies, standards of ethics and methods of participation. It promotes participation in the community and equitable representation, and guarantees the rights of artists to control how their culture is represented. These are the parts that work together to make a digital world that is sensitive to different cultures, works with other systems and is environmentally friendly. With feedback loops for constant improvement the idea model also sees the idea in the process of being enhanced or improved as the technology evolves, or as the community provides feedback. Through using ethical and sustainable digitisation processes that are scalable and adaptable, FADMF provides organisations, students and communities with a tool to preserve folk art.

2) Workflow

and Process Design (Acquisition, Metadata, Storage, Access)

The workflow design of the FADMF demonstrates the process of designing and building step by step and iterative procedures for the digitisation of folk art in an accurate and easy-to-access, and long-lasting manner. It consists of four major components: acquiring the data, handling the metadata, storing it, and accessing it. The first step in acquisition is the research, writing, and collection of folk art materials through community submissions, research and scholarly collaboration. Digital photographs of each artefact or performance are taken using high quality photography or recording devices to ensure validity and context of the material. The next step will be metadata management, which uses international standards such as Dublin Core and CIDOC-CRM to create descriptive, structural and administrative metadata. It documents details on its origin, composition, maker, method of production and its cultural significance. Multilingual content fields and controlled vocabularies ensure that everything is identical and accessible to people from every culture. Reliable and long-lasting online digital stores are used for storage. Data is stored in several systems, using the cloud and OAIS-compatible methods, and all to ensure security and the integrity of these files. Preservation information ensures that digital assets are discoverable and they become kept up to date. Digital platforms and open access libraries and virtual displays make it easier for academics and teachers, as well as the public, to access the information.

3) Roles

and Responsibilities of Stakeholders

FADMF is an effective Folk Art Digitisation Management model but only when there is a highly distributed workforce. Each person's skills and tasks are included in the digitisation process The framework identifies four key interest groups: culture protectors, technology experts, researchers and policy-makers. Folk artists, community elders, and cultural organisations are the people who are actually knowledgeable about their cultural heritage. Their role is to ensure that cultural materials are authentic, provide context and ensure that digitisation does not harm traditional values and practices. With their participation truth is guaranteed in culture and morality. Technical experts are responsible for the operational components, such as acquiring data, and creating information, digitization technology and the security of the digital records. They create systems that can work together and keep their data safe, which ensures that digital goods are accessible in the future. Researchers and scholars provide their analysis and writing service. They decipher the meaning of digitised materials, produce academic products and assess the quality of information. Their purpose is to join the common knowledge with well-established scientific analysis, which gives significance to the collection. Cultural Authorities and Policy Administrators have the responsibility to handle finances, ensure that intellectual property and ethical regulations are adhered to and regulate.

5. Implementation Strategy

1) Pilot

Study and Case Application

A pilot study was conducted on one regional folk art group selected on the basis of having an active artistic tradition and willingness to participate in digital preservation efforts to pilot the Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF). The test was done for validating the applicability of the framework, identifying implementation issues and improving operating manuals. At the beginning of the study, baseline information was collected on the following folk art types: cloth crafts, paintings and singing acts. To ensure that the materials were culturally accurate, artisans and community leaders worked together to identify and authenticate the materials. Digitisation was based on high resolution scanning, audio and video recording, and data tagging using standard templates which were compatible with Dublin Core and CIDOC-CRM. A prototype of digital library was created through the open source software Omeka. It has contextual linking with geotagging and language information fields. The research also tested the accessibility of the information through a live web site which enabled members of the public to view, students to learn, and community members to provide feedback. Metadata correctness, user satisfaction, and system interoperability were some of the evaluation criteria. The findings revealed that art materials were readily available, the quality of the archives were better and the community were very responsive. Difficulties with the implements of inputting of information were rectified through training classes and regular updates to keep the artists up to date with digital literacy.

2) Technical

Infrastructure Requirements

For FADMF to become operational, a robust, flexible and open technology infrastructure that can encompass the digitisation, preservation and distribution processes is required. The system is comprised of network components, hardware, and software that is designed for durability and usability for all. High-resolution cameras, 3D scanners, and small recording equipment are all technological items which are required in order to obtain correct data. Special computers and several storage systems ensure that information is stored securely. Cloud infrastructure (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud, or for academic purposes, let's say libraries) can be utilized to store data in a secure location that can be accessed at long distances by large-scale applications. Content Management Systems (CMS) such as Omeka, DSpace or CollectiveAccess are used for cataloguing and public show and Digital Preservation Systems (DPS) such as Preservica or Archivematica are used for safekeeping data for a long time. Using information standards including Dublin Core, CIDOC-CRM and VRA Core ensures interoperability between different systems and organisations. Networking and access protocols use the HTTP Secure (HTTPS), Application Programming Interface (API)-based data sharing, and Object Describe Process for HTTP (OAI-PMH) to collect data. Encryption, authentication of users and frequent backups all contribute to keeping data secure. The system also facilitates international interfaces, mobile site design and disability considerations for digital interaction by all users. The framework is also based on the idea of flexible design, allowing the model to be applied both to small-scale community projects and to cultural networks at a national level. Some other examples of being more sustainable include software updates and patches, data protection audits, and open source for cost savings.

3) Policy

and Ethical Considerations

Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) is built on the following ethical care and the following policies. It ensures that digitisation methods ensure intellectual property rights, cultural rights, and community control. Towards folk art as a living component of common memory and tradition, the framework's explanatory structure recognizes that folk art requires the protection of validity while at the same time being accessible to everyone. FADMF desires to have formal rules in line with international agreements such as the UNESCO 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage and WIPO's Traditional Knowledge Framework. These rules help ensure that credit is given for copyrights, license information and that users and groups receive their fair share of the benefits. Ethical considerations: The main ethical issues that will have to be considered are informed consent, cultural sensitivity, and data ownership. Digitisations should be taken with the consent of the communities and artists to ensure that those representations are faithful to their perceptions and circumstances. Systems (permission levels) are needed to restrict access to sensitive materials such as holy or traditional art. Trust and responsibility can only be maintained if authors of information are transparent about their work and are appropriately credited. The structure also promotes the responsible use of AI and prevents automatic copying or misusing of digital assets.

6. Results and Analysis

1) Evaluation

of Framework Performance

The review of FADMF big changes are in accuracy of information, ease of access, and user participation. The collaborative structure of the framework made it simpler for people to collaborate and ensured that digital records were authentic. Pilot tests showed that getting data was easy, that there was reduction in duplicate data and improved interaction with legacy systems. Reviewers and experts on-the-ground confirmed that it was culturally sensitive and helpful. On the whole, FADMF was scientifically sound together with an open society. It achieved its goals of conserving, managing and disseminating folk art in an organised but fluid digital environment that could function in a multiplicity of cultural environments.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Evaluation Metrics of FADMF Pilot Implementation |

|

|

Evaluation Criteria |

Achieved Score |

|

Metadata Accuracy |

9.2 |

|

Data Accessibility |

8.8 |

|

Community Participation |

9 |

|

Interoperability |

8.6 |

|

Technical Reliability |

9.1 |

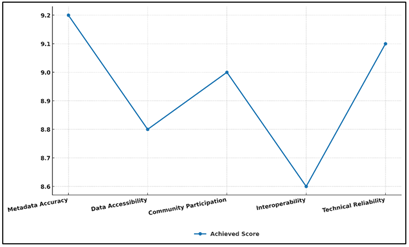

As can be seen from Table 2, the Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) was highly successful during its pilot rollout. The best score, 9.2, for information Accuracy indicates that the system is good at maintaining accurate, standardised and contextualised information using Dublin Core and CIDOC-CRM standards. Figure 2 presents the performance scores of FADMF over important evaluation criteria.

Figure 2

Figure 2 Performance Scores Across Evaluation Criteria

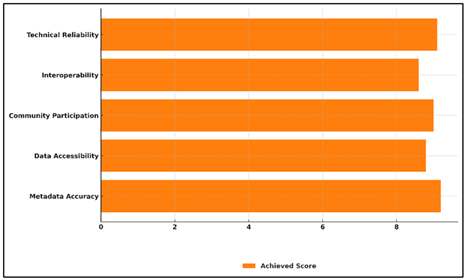

This ensures that all heritage records are actually real and compatible with each other. The framework's 8.8 rating for Data Accessibility indicates how effectively it works to provide users with a smooth access through the Omeka-based platform to access and connect with digital collections. Community Participation, which was given a score of 9.0, demonstrates the framework is committed to working together and includes everyone, as artists and local guardians participated in decision-making and gave the green light to material. Figure 3 displays all the achieved scores for each of the performance criteria tested.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Achieved Scores by Evaluation Criterion

The Interoperability score of 8.6 indicates that the system design of FADMF works well with current libraries of culture, thus making it easier for data to be shared between platforms. Technical reliability (9.1) determines the robustness of the system ensuring stability of speed and security of data backups.

2) Comparative

Analysis with Existing Models

FADMF is more suitable to adapt to community-led artform and intangible history compared to other digital archiving models such as OAIS and DCC. While the conventional models are about regulating institutions, FADMF combines democratic government and ethical digitalisation to empower communities. Its method is one of technical accuracy joined with cultural documentation, and thus is more inclusive and contextually accurate than other systems. Adding open source tools and information in multiple languages brings in better sustainability and interoperability of the same. In this manner, FADMF has been successful in linking global digital norms with localised needs in the cultural protection.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Comparative Performance Analysis of FADMF And Existing Models |

|||

|

Criteria |

FADMF |

OAIS Model |

DCC Framework |

|

Metadata Accuracy |

92 |

85 |

83 |

|

Interoperability |

86 |

80 |

78 |

|

Community Participation |

90 |

60 |

62 |

|

Accessibility |

88 |

82 |

81 |

|

Ethical Standards |

95 |

75 |

70 |

Table 3 demonstrates that the Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) was superior to the OAIS Model and the DCC Framework in a number of key rating criteria. Metadata Accuracy - FADMF achieves 92 which is higher than OAIS (85) and DCC (83) which proves it more accurate in cataloguing and presenting a context through flexible metadata standards, such as, Dublin Core, CIDOC-CRM etc.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Comparative Evaluation of Data Management Frameworks

Interoperability: FADMF's score is 86, which means it is compatible with other platforms and can easily transfer data, which is better than OAIS (80) and DCC (78). Figure 4 is a comparative graph of the performance of various data management frameworks. The most significant difference is in the Community Participation category where FADMF scores 90, which is much better than OAIS's score of 60 and DCC's score of 62. This is a reflection of its open and participatory approach that has local artists and culture bearers as active producers. In terms of accessibility, FADMF has a higher usage level (88) than OAIS (82) or DCC (81), which ensures everyone's ability to use it and connect with it with ease.

7. Conclusion

The Folk Art Digitisation Management Framework (FADMF) is a significant step in the preservation of the digital cultural history. It is an approach that integrates traditional knowledge systems with modern technology and takes a holistic approach to health care. Solving the issues with existing digital preservation models, FADMF builds an open, ethical, and technically correct framework which will ensure the documentation and dissemination of folk art forms in a sustainable manner. The framework is effective because it is culturally appropriate, community-driven and because digital systems are designed to be able to communicate with each other. Through its three key components - Content, Process and Governance - this organisation helps to link local cultural practice to institutional norms. The test implementation showed that the framework is adaptable to meet other requirements. It had improved information quality, improved modes of access, and good collaboration between artists, academic researchers and technologists. These results indicate that the model is applicable in different culture and technological environments. Even more, FADMF has ethical and policy components that protect the rights of artists and communities to their cultures and their intellectual property. The structure promotes trust and responsibility by concentrating on clear documents, fair management of data and educated permission. Because it is built on open source tools, standard metadata and cloud storage, it is designed to be capable of being deployed at a large scale and over a long period of time. Lastly, FADMF is not only maintaining folk art, but also giving it a new life as a dynamic form of culture, which can be enjoyed by all people around the world. It shifts digitisation from a technical work process to a cultural process which is done by and with people. So, the framework can be used as a model for future heritage digitisation projects. This demonstrates that saving culture in the digital age has to be inclusive open to anyone, ethical and supported by technology to ensure that traditions and community identity is kept alive.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Bortolotto, C. (2021). Commercialization without Over-Commercialization: Normative Conundrums Across Heritage Rationalities. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(8), 857–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2020.1858441\

Chong, H. T., Lim, C. K., Ahmed, M. F., Tan, K. L., and Bin Mokhtar, M. (2021). Virtual Reality Usability and Accessibility for Cultural Heritage Practices: Challenges Mapping and Recommendations. Electronics, 10(12), Article 1430. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10121430

Corallo, A., Del Vecchio, V., Lezzi, M., and Morciano, P. (2021). Shop Floor Digital twin in Smart Manufacturing: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 13(23), Article 12987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312987

Ercan, F. (2020). An Examination on the use of Immersive Reality Technologies in the Travel and Tourism Industry. Business and Management Studies: An International Journal, 8(2), 2348–2383. https://doi.org/10.15295/bmij.v8i2.1510

Innocente, C., Ulrich, L., Moos, S., and Vezzetti, E. (2023). A Framework Study on the use of Immersive XR Technologies in the Cultural Heritage Domain. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 62, 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.06.001

Jadhav, N. (2025). The Impact of Physical Education on Academic Performance and Cognitive Development Among Collegiate Students. International Journal of Research and Development in Management Review, 14(1), 200–203. https://doi.org/10.65521/ijrdmr.v14i1.642

Kontopanagou, K., Tsipis, A., and Komianos, V. (2024). Fostering Cultural Awareness in Museums and Monuments by Employing Extended Reality. Global Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology, 13, Article 555870. https://doi.org/10.19080/GJAA.2024.13.555870

Litvak, E., and Kuflik, T. (2020). Enhancing Cultural Heritage Outdoor Experience with Augmented-Reality Smart Glasses. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 24(6), 873–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-020-01366-7

Maietti, F. (2023). Heritage Enhancement through Digital Tools for Sustainable Fruition: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability, 15(15), Article 11799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511799\

Marino, A., Pariso, P., and Picariello, M. (2022). Digital Platforms and Entrepreneurship in Tourism Sector. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 9(4), 282–303. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2022.9.4

Okanovic, V., Ivkovic-Kihic, I., Boskovic, D., Mijatovic, B., Prazina, I., Skaljo, E., and Rizvic, S. (2022). Interaction in Extended Reality Applications for Cultural Heritage. Applied Sciences, 12(3), Article 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031241

Pratisto, E. H., Thompson, N., and Potdar, V. (2022). Immersive Technologies for Tourism: A Systematic Review. Information Technology and Tourism, 24(2), 181–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-022-00228-7

Puig, A., Rodríguez, I., Arcos, J. L., Rodríguez-Aguilar, J. A., Cebrián, S., Bogdanovych, A., Morera, N., Palomo, A., Piqué, R., and Palomo, A. (2020). Lessons Learned from Supplementing Archaeological Museum Exhibitions with Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality, 24(2), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-019-00391-z

Schuhbauer, S. L., and Hausmann, A. (2022). Cooperation for the Implementation of Digital Applications in Rural Cultural Tourism Marketing. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 16(1), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-08-2020-0171

Skublewska-Paszkowska, M., Milosz, M., Powroznik, P., and Lukasik, E. (2022). 3D Technologies for Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation: Literature Review for Selected Databases. Heritage Science, 10, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00633-x

Thomas, G. H., and Douglas, E. J. (2024). Resource Reconfiguration by Surviving SMEs in a Disrupted Industry. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(1), 140–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.2009489

Van Nuenen, T., and Scarles, C. (2021). Advancements in Technology and Digital Media in Tourism. Tourist Studies, 21(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797621990410

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.