ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Community-Driven AI Models for Cultural Art Education

Jatin Khurana 1![]()

![]() ,

Shikha Gupta 2

,

Shikha Gupta 2![]() , Dr. Zuleika

Homavazir 3

, Dr. Zuleika

Homavazir 3![]()

![]() , Sandip Desai 4

, Sandip Desai 4![]() , Simranjeet Nanda 5

, Simranjeet Nanda 5![]()

![]() ,, Yaduvir Singh 6

,, Yaduvir Singh 6![]()

![]()

1 Chitkara

Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University, Himachal Pradesh,

Solan, India

2 Assistant

Professor, School of Business Management, Noida international University,

Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Professor, ISME - School of

Management & Entrepreneurship, ATLAS Skill Tech University, Mumbai,

Maharashtra, India

4 Department of Electronics and

Telecommunications, Yeshwantrao Chavan College of Engineering, Nagpur,

Maharashtra, India

5 Centre of Research Impact and

Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

6 Assistant Professor, Department of

Computer Science and Engineering (AI), Noida Institute of Engineering and

Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This paper

discusses the concept of community-based engagement in the implementation of

artificial intelligence in cultural art education, how artificial

intelligence can be used to facilitate creative learning without affecting

the cultural authenticity. A four-week student-teacher-local artisan case

study established that AI considerably promoted creative interactions,

multimodal learning, as well as cultural cognition. Nevertheless, the results

also provide evidence that the output of AI can be significantly biased in a

symbolic way and the necessity of the community verification and human

control is evident. Repeat human in the loop refinement enhanced cultural

precision and enhanced the exchange of knowledge between generations. It is

concluded that when integrated into an ethically informed participatory

approach, which focuses on local cultural knowledge, AI can be useful in

supplementing cultural art education. It outlines the necessity of databases

rich in culture, effective governance and ongoing participation by the

community in order to achieve responsible and meaningful implementation. |

|||

|

Received 13 January 2025 Accepted 06 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Jatin

Khurana, jatin.khurana.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6639 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Cultural Art Education, Human-In-The-Loop,

Generative AI, Cultural Authenticity, Participatory Learning,

Retrieval-Augmented Generation, Digital Creativity, Heritage Preservation, AI

In Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Within the blistering digital environment, the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) into cultural art education is a revolutionary break and a new way of how societies can maintain creativity, pass on heritage, and develop cultural knowledge. The cultural art education is entering a new era, which has traditionally been premised on the local tradition, oral narrative, and community engagement, and now AI systems can support the artistic process, democratize the knowledge access process, and enhance the collaborative learning effect. However, the transformation has also its darker side of concerns related to the concept of ownership, authenticity and preservation of culture in the world that is expanding more and more towards the algorithm-drive AlGerafi et al. (2023). A solution to this is to balance between technological advancement and cultural identity with the introduction of community-oriented AI models. These models are elaborated based on the aspects of participatory design, which emphasize the local interaction, data sovereignty, co-creation between human communities and intelligent systems. Instead of turning AI into an exogenous technological actor, the community-based paradigm looks at it as a mediator of shared intelligence, and communities as active participants in training, interpreting and applying algorithms De Winter et al. (2023). Such systems incorporate the localized knowledge, practices and beauty perceptions in the AI systems, which means that the digital tools should capture the real cultural views and not to homogenize them. In the academic setup, this mechanism reinvents the learning process. Students are not the passive product consumers of the outputs of the algorithms but they are active participants in the creation and critique of the AI-mediated experiences of art. Learners can access the cultural information through interactive platforms and generative models and adaptive feedback to stimulate imagination, critical reflection and problem-solving Hamal et al. (2022). The community-based AI systems also allow flexible relationships between cultural establishments, educators, and local creators. Additional ways that museums, art schools and community organizations can contribute to common stores of cultural information such as images, sounds, oral histories, or design patterns, which are inputted into open AI models Williamson et al. (2020). When trained in ethical, inclusive government systems, these models will be effective tools to save the art forms at risk, restore the lost trades, and promote cross-cultural discussion. Communities, by going through cycles of iteration based on learning, help to verify AI outputs, fix biases, and re-interpret creative artifacts, in context, and generate a self-renewing learning cycle, reflection, and renewal Fawns (2022).

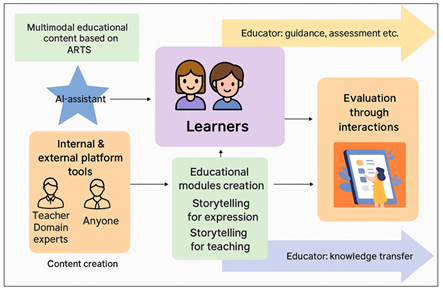

Figure 1

Figure 1 CULTARTS: AI-enhanced storytelling framework for

learners and educators.”

On a larger societal scale, such a solution is in line with the culture development and digital inclusion objective of sustainability. The decentralization of technology under community-driven AI encourages fair distribution of creative technology so that vulnerable groups are allowed to project their cultural stories in the virtual realm as shown in Figure 1It helps connect the generations and enhances local empowerment as well as helps sustain the culture in accordance to the global frameworks like the UNESCO agenda on heritage and education towards sustainable development. The research paper discusses the design and use of community-based AI models as approaches to facilitating inclusive, innovative, and cultural responsive art education. It attempts to conceptualize a framework that would combine AI technology and participatory pedagogy, and how the shared work of people and machines can help enhance cultural identity, become innovative, and keep alive the various artistic forms that characterize humanity.

2. Conceptual Evolution

The implementation of the concept of artificial intelligence in art and cultural learning has developed through the simple computer-assisted instruction to advanced, community-based learning environments. In the beginning, AI in education was aimed at automatization of routine procedures and the creation of personalized learning processes. With time, these systems evolved to facilitate innovative exploration, adaptive storytelling and experiential cultural interaction Gong (2023). Here, the development of human-centric co-creation AI models is a major conceptual transformation, the shift to technology-centric innovation to human-centric, where communities do not only control the content, but also the logic and ethics of machine AI. The development of The conceptual sphere of AI in education is conditioned by the change in the interaction mode, the mode of passivity to the mode of participation. The first applications of AI were instructional machines that displayed preprogrammed knowledge, whereas the present ones are more concerned with dialogue, personalization, and innovation. As with the growing call in the practice of cultural art education, this trend has been linked to a turning towards models that are conscious of contextual authenticity and local cultural articulation Yefimenko et al. (2022). Together with machine learning, natural language processing, and generative algorithms, community-based systems have the potential to read and analyze and access cultural narratives to generate art. This shift is a paradigm shift because the interaction between the human and machine is substituted by the collective intelligence whereby the boundaries between the creator, learner and algorithm are blurred and the infinite cycle of collaborative meaning-making is enacted Al Darayseh (2023). Participatory AI suggests a participatory pedagogical model, which is created on the basis of collaboration, diversity, and empowerment. The systems of participation enable communities, students and educators in co-creation and authentication of the data and processes that drive the AI tools in comparison to the traditional top-down educational structures. This involvement in the cultural art education transforms the classrooms into the ecology of creativity where the conventional forms of art, local histories as well as indigenous aesthetics are digitalized and reorganized in an active way Nicácio and Barbosa (2018). Students are not only consumers of AI but the creators of data sets, result determiners, in addition to offering cultural specificity to computing systems. The habit also leads to the occurrence of cultural intelligence, a balance between the conventional learning process and the digital fluency and the augmented sense of ownership of the creative technologies Yu et al. (2021).

3. Research Design and Methodology

The section provides a description of the methodological framework that is applicable to investigate the application of community-driven AI models in cultural art education. The design incorporates qualitative and participatory approach to engage the multifaceted relationships among technology, creativity and community relations Davis et al. (2015). It places great focus on collaborative investigation, co-creation, and ethical management of data in order to make sure that both technological and cultural aspects are taken into consideration. The qualitative research method was mostly used, with some aspects of mixed methods that were used in an effort to describe and experience the research. This method allows the comprehensive comprehension of the idea of community involvement and cultural education as contributed by AI technologies Rezwana and Maher (2022). The qualitative aspect aimed at defining the perceptions, creative process, and collective meaning-making by observation, interviews, focus group discussions. In the meantime, quantitative aspects were added by the use of structured feedbacks and engagement rates based on workshops and internet platforms Tang (2021).

Triangulation may be achieved by combining both strategies, which guarantees the reliability of the data and offers more information about the educational and social effects of AI-supported culture art programs.

Step -1] Data Collection (Workshops, Focus Groups, Case

Studies)

· The participatory workshops, focus group discussions and the case study implementations constituted the data collection phase of this study.

· Workshops were interactive spaces, where educators, students and community artists worked with AI tools to create, comprehend and clarify creative works of art based on local cultural backgrounds.

· To understand the expectation, experience and thoughts of the participants on the role of AI in the creative co-production and cultural learning, the Focus Groups were held, before and after the workshops.

· Case Studies were created in certain communities or schools to see the effects of AI integration over the long term, where the integration of AI into their activities, skills and perceptions of culture were recorded.

· Each of the sessions was recorded on audio, transcribed, and complemented with the digital recording of AI-generated output and interaction with users.

Step -2] Selection of AI Tools and Platforms

· Various AI platforms were used to describe different capabilities:

· Contextualization Content and information grounding of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) models on local heritage datasets.

· Dialogic learning, narrative co-construction, and text-based interpretation ChatGPT ChatGPT can be used to facilitate dialogic learning, narrative co-construction, and text-based interpretation.

· Midjourney and DALLE in support of visual co-creation, which provides the participants to encode cultural themes into artwork.

· The process of simulated real-time creative ideation and community validation was done with the help of collaborative AI platforms (e.g., degdegKobi or RunwayML).

· The choice was based on the principles of accessibility, multilingual assistance and flexibility of open data in order to be inclusive and culturally relevant.

Step -3] Participant Demographics and Community

Involvement

· The participants in the study were about 60 participants in three categories:

· Art and cultural studies program students and Educators,

· Local Artists and Artisans of traditional knowledge systems, and

· Community Stakeholders, who are participating in Cultural preservation programs.

· Purposive sampling was used to select the participants so that there could be diversity in terms of age and cultural background and be digitally literate.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Participant Profile and Data Collection Overview |

||||

|

Participant

Group |

Number

(N) |

Engagement

Method |

Role

in Study |

Expected

Contribution |

|

Students

(Undergraduate / Postgraduate) Tang (2021) |

30 |

Workshops

and Focus Groups |

Co-creators

and learners using AI tools |

Feedback

on creative engagement and learning outcomes |

|

Educators / Art Instructors Bamanikar et al. (2025) |

15 |

Training sessions and

observation |

Facilitators and reflective

observers |

Insights on pedagogical

adaptation and teaching innovation |

|

Local

Artists / Artisans Huang (2023) |

10 |

Co-creation

labs and demonstrations |

Cultural

experts and dataset contributors |

Ensure

cultural authenticity and local artistic integration |

|

Community Leaders / Curators |

5 |

Interviews and policy

dialogues |

Governance and ethical

oversight |

Perspectives on heritage

preservation and policy implications |

The integration of the formal institutions of education with the community based organizations created an atmosphere of participatory that reflected the real world collaboration. Interaction was in the form of co-creation paradigm where the involvees provided data, authenticated output, and feedback on cultural integrity and aesthetic worth.

Step -4] Analytical Framework

The implementation, observation, reflection, and refinement were implemented through a design-based research (DBR) framework. They were supplemented with the thematic analysis that was used to discover recurring concepts, attitudes, and cultural representations in qualitative data. Key dimensions that were targeted in the coding process included:

Attitudes toward AI as a co-creative aid,

Artificial intelligence cultural relevance, and authenticity,

Inclusiveness and ethical consciousness, and

4. Proposed Community-Driven AI Framework for Cultural Art Education

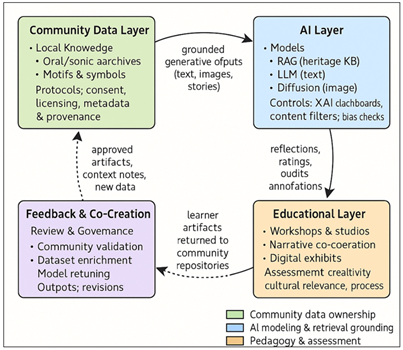

In this section, the conceptual and operational design of the proposed Community-Driven AI Framework will be presented and an effort to change cultural art education into a participatory, inclusive, and technologically adaptive ecosystem. The framework connects the areas of artificial intelligence, cultural heritage, and pedagogy through encouraging the collective creativity, ethical AI implementation, and sustainable cultural learning. It works as an active mechanism made of interrelated layers; Community Data, AI Model, Educational Process, and Feedback and Co-Creation, which together support natural interaction between the learners, the educators and the cultural practitioners. The suggested framework assumes the four-layered architecture that provides the cooperation of human actors and AI-based systems. The process starts with the community data collection, moves to training AI models and content generation and finishes with the collaborative learning and feedback. The cyclical nature of this design will help in ensuring that all the AI artifacts are culturally validated prior to their educational implementation and that they will be consistent with the values of the community. The base is the Community Data Layer which is the human and cultural capital of the ecosystem. It includes digital collections, folk tales, art samples on a visual basis, oral histories and local aesthetics gathered by artists, artisans and educators. Curation of data adheres to the principles of participatory practices in that the contributor will have ownership and control of the usage of their materials. Traceability and contextual integrity are guaranteed by metadata tagging. This layer upholds the sovereignty of data making sure that the representation of the culture is true, inclusive and morally obtained.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Community–AI–Learning

Cycle Framework

With the help of fine-tuning (locally sourced datasets), generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and DALLE are customized to generate culturally contextualized art forms, stories, or visual interpretations. The algorithms are tracked by using explainable AI (XAI) dashboards in order to guarantee transparency in decision-making. This layer will make the AI not passive but an active partner with the ability to learn and change according to human input. The Educational Layer makes outputs of AI generated outputs interactive and learner-oriented pedagogy. The concepts of cultural art are explained on the basis of project-based and experiential learning, students interact with AI like co-creators. Online studios, online galleries, and design workshops enable students to engage with heritage-informed imagination and acquire digital literacy. The core of keeping the cultural authenticity and educational integrity is the Feedback and Co-Creation Loop. Following every artistic product, the AI-generated work is reviewed by community members, a group of artists, educators, or elders of the culture to check the content on its accuracy, representation, and symbolism. Their comments are used to refine the algorithm, enhance the dataset and modify the pedagogy.

It is an iterative process that makes AI systems become ethical, guided by the real-world culture understanding, and not by abstract data. The loop also endorses collective authorship, which appreciates the role of human creativity, as well as contributive intelligence of AI. Eventually, this recurrent learning process results in culturally aware AI models that are dynamically changing to the needs of the community and artistic fashions.

5. Experimental Implementation

This part will be a practical application of the suggested community-based AI framework to a community-based cultural art education context. As illustrated in the case study, AI tools, community knowledge and participatory pedagogy were combined to create a collaborative creative atmosphere between students, educators and practitioners of local cultures. The case study was participated in a local art learning community that collaborated with a local school that focused on visual and cultural arts. The main objective was to determine whether AI-aided co-creation would allow promoting cultural learning, encouraging creative interaction, and helping to preserve the regional artistic tradition.

There were 20 senior secondary students, 4 art educators and 5 local artisans who has expertise in traditional forms of art like folk murals, textile motifs, and oral narrative art. The show was conducted in the form of a four-week cycle whereby the programmers collaborated with AI tools to create works of art and cultural stories based on community-sourced datasets. The application placed special focus on real cultural representation, cooperative learning and community validation through repetitions. Its implementation was organized as follows:

1) Community

Knowledge Gathering

The digital samples of the traditional patterns, folk stories, folklore motifs, symbols, and color palettes were offered by local artisans and educators and were curated and tagged to cultural accuracy.

2) AI

Model Preparation

Tools used included:

· ChatGPT for narrative expansion, cultural dialogue, and text-based storytelling,

· Midjourney/DALL·E for generating visual motifs and reinterpreted cultural imagery,

· RAG-based pipelines for grounding generative outputs in the curated cultural repository.

3) Creative

Workshops

AI tools were used by students to remake the conventional cultural ideas into digital arts forms and comparing the AI generated designs with the references created by people.

4) Community

Review Sessions

AI outputs were also checked by local artisans, and they gave feedback on symbolism, cultural conformity, and aesthetic correctness.

5) Iterations

and Refinement

The AI outputs were also refined by the participants according to the comments by the artisans, resulting in the final pieces of art that were displayed in a virtual exhibition. The feedback of the community said that AI-generated art opened up new creativity possibilities, yet, without experimenting with cultural elements.

Table 2

|

Table 2 AI Tools and Their Functions in the Implementation |

||||

|

Tool

/ Platform |

Functionality |

Role

in Case Study |

Benefits |

Limitations |

|

ChatGPT |

Text

generation, narrative expansion, dialogic learning |

Create

cultural stories, explain symbolism, assist scripting |

Fast

ideation; linguistic flexibility |

Occasional

cultural misinterpretation |

|

Midjourney / DALL·E |

Generative visual models |

Produce motifs, scenes,

cultural reinterpretations |

High visual creativity;

multiple variations |

Can blend unrelated cultural

symbols |

|

RAG

Pipeline |

Retrieval-Augmented

Generation |

Ensure

cultural grounding and data accuracy |

Reduces

hallucinations; respects local data |

Requires

high-quality curated datasets |

|

Digital Drawing Apps |

Manual editing and

refinement |

Add hand-drawn details to

AI-generated images |

Encourages hybrid human–AI

creativity |

Requires skill training |

|

Community

Review Tools |

Annotation

and approval |

Validate

cultural authenticity |

Ensures

cultural safety |

Time-intensive |

The artisans also valued how responsive the AI was to them but insisted on the human element in the production of the piece, particularly when it comes to such spiritual imagery and local iconography. Students reported a great level of engagement as they believed that AI made traditional art more accessible, exciting, and contemporary. They were fond of trying the different stylistic variations and they were motivated by the instant feedback. The majority of the students claimed that the use of AI increased their level of confidence in digital skills and cultural sensitivity. According to teachers, learners have been more active in group discussions particularly when comparing AI-generated designs and traditional art objects. It is through this reflective dialogue that this critical thinking and cultural literacy were improved.

6. Results and Discussion

The introduction of the community-based AI model led to the clear data that AI can significantly boost student engagement and cultural education, in case of the combination with participatory practices used. The use of AI-assisted tools made students more interested in traditional motifs, which, according to them, offered more possibilities of experimentation in the environment where there were no inhibitions. This exploration sparked additional reflection on the symbolism of the culture that led to improved discussions within the classroom that increased cultural awareness of the students. Teachers observed that the system with the assistance of AI offered more active discussion, in particular, when students compared AI-generated pictures with the actual cultural units.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Accuracy Comparison: AI Vs. Human-Reviewed Outputs |

|||

|

Parameter |

AI

Output (Before Review) |

After

Community Review |

Change |

|

Cultural

Authenticity Score (1–10) |

5.8 |

8.7 |

2.9 |

|

Symbol Accuracy (%) |

63% |

91% |

28% |

|

Motif

Consistency |

Moderate |

High |

Improved |

|

Presence of Cultural Errors |

Frequent |

Rare |

Reduced significantly |

|

Visual

Appeal (Learner Rating) |

8.2 |

9.1 |

Slight

improvement |

Their responses revealed that AI is not sufficient to ensure cultural accuracy and that the human monitoring is obligatory to ensure the integrity of heritage. It can be stated that the process of the iterative review transformed the quality of new artworks into its cultural form, which validates the usefulness of the human-in-the-loop approach.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Student Engagement Indicators |

||

|

Engagement

Category |

Observation |

Level |

|

Creative

Exploration |

Students

tried multiple AI variations |

High |

|

Participation in Discussions |

Increased comparison between

AI and traditional art |

High |

|

Digital

Tool Confidence |

Improved

over time |

Medium–High |

|

Cultural Curiosity |

Students asked more

questions about motifs |

High |

|

Collaboration

with Artisans |

Active

and respectful participation |

Medium–High |

The AI tools that were used in the study played a complementary role. ChatGPT was useful in encouraging the exploration of narratives and assisting students in sharing cultural concepts through text, whereas visual generators such as midjourney and DALLE promoted the act of creative reinterpretation of artistic patterns. Specifically, the Retrieval-Augmented Generation pipelines proved to especially effective when grounding outputs on the basis of real cultural data and minimizing errors and enhancing the aspect of cultural alignment. A combination of these tools formed the rich multimodal learning environment which promoted the creative and the cultural comprehension.

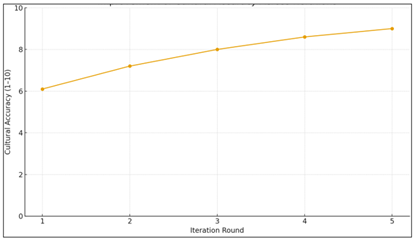

Figure 3

Figure 3 Improvement of Cultural Accuracy Across Iterations

The line chart shows that cultural correctness of AI-generated artifacts was increased with each repetition of the review process involving students, educators, and local craftsmen. The initial version provides a moderate score of about 6.1 of accuracy, the initial outputs tended to confuse symbolic components or simply misinterpret classical motifs as shown in Figure 3. As the participants contributed to the error correction, data additions, and prompts, the accuracy of cultural data improved gradually. With the third iteration, the accuracy was 8.0 with a significant enhancement achieved because of the human-in-the-loop review. The last version got to approximately 9.0 which meant that repeated testing and joint optimization actually made the AI results go in line with real cultural taste. The positive trend indicates clearly that the fidelity, consistency and cultural relevance of AI-generated art would be greatly improved with the help of participatory validation, which proves the importance of community-based oversight in culturally-oriented AI systems.

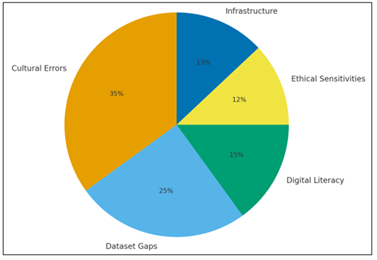

Figure 4

Figure 4 Distribution of Challenges Encountered

The size of the gaps in datasets was about 25, which highlights the limitation of using small or incomplete cultural archives that made the AI models generate the generic or inaccurate output according to Figure 4. The challenges on digital literacy were 15% of the total, which can be explained by a necessity to train the students and some participants to make efficient use of AI tools. Ethical sensitivities, which constituted 12% were due to the issue of misappropriation of culturally sensitive or sacred symbols. Problems with infrastructure comprised 13% as this was mainly caused by poor internet connectivity and low computational resources. Student and community responses highlighted the effect the project had on the community. The hybrid human-AI creative process gave the students a feeling of empowerment, as well as increasing their confidence in intertwining digital techniques and the cultural subject matter. The updated format of showing local heritage revitalized by the community members and the end digital exhibition was an appreciated one, reflecting the social value of the project.

7. Conclusion

This research paper proves that ethically oriented and participatory framework of community-driven AI models can significantly contribute to cultural art education. The findings indicate that AI tools increased student engagement and spurred creative exploration and made them reflect more on cultural identity. Nevertheless, the paper also underlines that AI will not suffice to guarantee cultural accuracy; instead, human control (especially of local artisans and experts of the specific culture) will be required to justify the symbolic meaning and preserve the heritage integrity. Human-in-the-loop approach proved to be a powerful means of perfecting AI results and enhancing cultural authenticity, as well as ensuring a better knowledge transfer between generations. Although AI integration enhanced the learning process, a number of difficulties were identified, such as cultural misunderstanding, data constraints, digital illiteracy, and ethical suspicion. Altogether, the project affirms that the power of AI is not about substituting cultural knowledge but the instrument that enhances the knowledge community, reactivates the old traditions of art, and creates the fresh approaches to creative representation. As an aid to the preservation of the cultural heritage and a connector to the digitally richer future, AI can be a useful partner in the effort to keep the cultural elements alive, under proper guidance, with the help of transparency and ownership of the community.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Al Darayseh, A. (2023). Acceptance of Artificial Intelligence in Teaching Science: Science Teachers’ Perspective. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, Article 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100132

AlGerafi, M. A. M., Zhou, Y., Alfadda, H., and Wijaya, T. T. (2023). Understanding the Factors Influencing Higher Education Students’ Intention to Adopt Artificial Intelligence-Based Robots. IEEE Access, 11, 99752–99764. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3314499

Bamanikar, A. A., Kale, R., Pagar, H., Wakode, R., and Sajjanshett, M. (2025, April). Virtual Mouse using Hand Gesture and Voice Recognition. International Journal of Advances in Electronics and Communication Engineering (IJAECE), 14(1), 25–32.

Davis, N., Hsiao, C.-P., Popova, Y., and Magerko, B. (2015). An Enactive Model of Creativity for Computational Collaboration and Co-Creation. In Creativity in the digital age (109–133). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-6681-8_7

De Winter, J. C. F., Dodou, D., and Stienen, A. H. A. (2023). ChatGPT in Education: Empowering Educators Through Methods for Recognition and Assessment. Informatics, 10(4), Article 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10040087

Fawns, T. (2022). An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy–Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education, 4, 711–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00302-7

Gong, C., et al. (2023). Generative AI for Brain Image Computing and Brain Network Computing: A Review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, Article 1203104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1203104

Hamal, O., El Faddouli, N. E., Alaoui Harouni, M. H., and Lu, J. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in Education. Sustainability, 14(5), Article 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052862

Huang, Y. (2023). The future of generative AI: How GenAI would Change Human–Computer Co-Creation in the Next 10 to 15 years. In Companion Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (322–325). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3573382.3616033

Nicácio, R. T., and Barbosa, R. L. L. (2018). Understanding Higher Education Teaching, Learning and Evaluation: A Qualitative Analysis Supported by ATLAS.ti. In Computer Supported Qualitative Research: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Qualitative Research (393–399). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61121-1_33

Rezwana, J., and Maher, M. L. (2022). Designing Creative AI Partners with COFI: A Framework for Modeling Interaction in Human-AI Co-Creative Systems. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1145/3519026

Tang, Z. (2021). Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Art Education: Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 39(4), 583–597.

Williamson, B., Bayne, S., and Shay, S. (2020). The Datafication of Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Issues and Perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1748811

Yefimenko, L., Hörmann, C., and Sabitzer, B. (2022). Teaching and Learning with AI in Higher Education: A Scoping Review. In M. E. Auer, A. Pester, and D. May (Eds.), Learning with Technologies and Technologies in Learning (333–350). Springer.

Yu, H., Evans, J. A., Gallo, D., Kruse, A., Patterson, W. M., and Varshney, L. R. (2021). AI-aided Co-Creation for Wellbeing. In A. Gómez de Silva Garza, T. Veale, W. Aguilar, and R. Pérez y Pérez (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC 2021) (453–456). Association for Computational Creativity.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2025. All Rights Reserved.