ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Deep Learning in Lithographic Process Optimization

Dr. Naresh Kaushik 1![]()

![]() ,

Sovers Singh Bisht 2

,

Sovers Singh Bisht 2![]()

![]() , Dr. Zafar Ali Khan N 3

, Dr. Zafar Ali Khan N 3![]()

![]() , Simran Kalra 4

, Simran Kalra 4![]()

![]() , Gourav Sood 5

, Gourav Sood 5![]()

![]() , Rupa Fadnavis 6

, Rupa Fadnavis 6![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, UGDX School of Technogy, ATLAS Skill Tech University, Mumbai,

Maharashtra, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (DS), Noida Institute

of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Professor, Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency University,

Bangalore, Karnataka, India

4 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Yeshwantrao Chavan

College of Engineering Nagpur, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The rapid advances in the development of semiconductor devices have placed control, precision and yield optimisation in the printing process under pressures hitherto unseen. In the past few levels of technology, empirical and physics-based models worked well. But in advanced lithography, they have a hard time capturing the complicated non-linear relationships of exposure, focus, resist and etching parameters. New developments in deep learning (DL) have opened up the use of predictive modelling, finding flaws and adaptable optimisation in the printing process in new ways. This research explores how deep learning models such as convolutional neural network (CNN), recurrent neural network (RNN), generative adversarial network (GAN) and transformer can be applied to enhance the lithography process. Data from litho tools and physics-based simulation are used to train models that can be used to predict regularity of critical dimensions (CD), mistakes in overlays, and the accuracy of resist profiles. Model generalisation is enhanced with dimensionality reduction techniques and feature extraction techniques. Mean absolute error (MAE), R2, and process window gain are performance measures and are helpful in evaluation. The study also speaks about new areas of research that require more attention. |

|||

|

Received 12 January 2025 Accepted 05 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr.

Naresh Kaushik, kaushik@atlasuniversity.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6633 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Lithography, Deep Learning, Process Optimization,

Reinforcement Learning, Physics-Informed Neural Networks, Semiconductor

Manufacturing |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The chip business is always trying to get smaller, faster, and cheaper because according to Moore's Law, things will keep getting better and better. At the center of this technological development is a process known as lithography, and it is the key process that enables the transfer of complex circuit structures onto a semiconductor chip. As device shapes have got smaller and smaller (nanometres) it's becoming more difficult to maintain precision in the lithography process because the exposure dose and focus, the photoresist chemistry and the etching afterwards are all very dependent on each other. Any changes in these factors can cause the end pattern to be off which will eventually impact yield, gadget performance, and the cost of production. So, improving lithography methods have become important part of making high tech semiconductors. Traditional ways of modelling lithography depend a lot on models based on physics and process control that is based on experience. In the past, by using optical and resist models as well as careful testing, reliable predictions of pattern profiles and process windows have been made Guan et al. (2023). But as feature sizes approach the limits of the material and the real world, it has become more difficult for these methods to record complex and high dimensional process behaviours. It's not possible to just use traditional modelling and rule based optimisation because equipment is getting more complicated and exposure and resist response changes randomly.

Also, the tremendous amounts of process data that modern lithography tools generate from sensors, internal measurement, and modelling output makes the process of finding ideas that can be used easier and harder. In the last few years, artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL) are major changes in the way semiconductors are made. Deep learning models are good at learning complicated and nonlinear maps from big multidimensional datasets Guan et al. (2024). This makes them perfect for dealing with the complicated printing processes. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) could be used to show the dependencies between resist profiles and chip patterns in space, and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) could be used to show the dependencies between process drift and tool stability over time. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are good at making synthetic lithography patterns for data enhancement and resist picture prediction. Also, transformer designs are beginning to enable the integration of data from optical, thermal and mechanical sources in novel ways Chen et al. (2023). The use of deep learning in printing goes through many steps of the process. DL-based models, for example, can figure out the best settings for controlling the brightness and focus so that critical dimension (CD) change is kept to a minimum and process windows are maximised. In the process of growing the resist and etching, deep models can predict how the character should change in the case of errors and find errors in time before they spread further. In advanced process control (APC), reinforcement learning methods make it possible for flexible feedback loops to tune process parameters all the time Wu et al. (2022).

2. Literature Review

1) Overview

of lithography process stages (exposure, focus, resist, etching)

The lithography technique is the most important part of the manufacturing of semiconductors. It creates complicated schemes on silicon plates. It has several steps that work in conjunction with one another to ensure the pattern is accurate and the dimensions are correct. These steps are exposure, focus, resist processing and etching Zhao et al. (2022). During the exposure process, the ultraviolet (UV) or extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light is used to expose a circuit design from a photomask onto a photoresist chip. It is very important to have a precise control of the focus and exposure dose, as differences of only a few nanometres can cause line edge roughness or variation of the critical dimension (CD). In the next phase photoresist, molecular processes caused by light change to how easily the resist can be dissolved Zhao et al. (2023). The profile of a resist is then further determined by the post exposure bake (PEB) and development processes. Process factors such as temperature, bake time, and concentration of a developer have a direct impact on the end pattern results. Finally, in the etching stage, the regularity, the selectivity and the anisotropy are carefully balanced to transfer the design of the resist onto the base of the chip. This can be done by either dry plasma or wet etching. Litho is very complex and sensitive to noise, pollution and tool drift since the processes interact with each other during these steps Zhao et al. (2024).

2) Review

of conventional modeling and control techniques

In the past, physics-based modelling and empirical control methods were applied to the lithography process to make it better. To determine how patterns will form, the strict lithography simulators use optics, chemistry, and diffusion equations from first principles. An illustration of this is optical proximity correction (OPC) models and resist development simulators. These models can be interpreted and are physically accurate but they need to be calibrated a lot and take a lot of computing power Shutsko et al. (2022). Because they are easy to use and quick, empirical models based on polynomial regression or response surface methods have been used a lot for dose and focus tuning. But they do not always work in the presence of a change in process conditions or equipment drift. Advanced process control (APC) systems such as run-to-run (R2R) and feedforward-feedback loops have made processes more stable by constantly changing the tool settings based on feedback from the measurement. Model based control methods like predictive control and Kalman filtering have also been applied to minimize the impact of changes in exposure or overlay that occur over time Mulla et al. (2024). These advances have not stopped the limitations of conventional approaches with the increasing complexity of processes that are reaching even smaller dimensions at sub-5 nm nodes.

3) Existing

machine learning applications in lithography

Machine learning (ML) has made it possible for predictive modelling, process tracking and control optimisation to be done in lithography in new ways. Early machine learning techniques included decision trees, support vector machines (SVMs) and Gaussian process regression that were used to sort defects, predict CDs, and figure out process windows. As more data became available and computers were faster, deep learning methods began to take over as they were better at extracting features and generalising them Zhao et al. (2024). Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been successfully applied to the aerial image prediction, simulation of resist profiles and defect finding of patterns. Compared to traditional tools based on physics, the modelling times of CNN are much quicker. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been promising for producing fake data and better masks while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have been used to understand how tool stability and process drift evolve over time Kang et al. (2024). Table 1presents comparative studies of the application of deep learning in lithography optimization.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Summary of Related Work in Deep Learning for Lithographic Process Optimization |

||||

|

Objective |

Lithography Stage |

Architecture |

Key Metrics Used |

Main Outcome |

|

Aerial image prediction |

Exposure |

CNN |

MAE, RMSE |

Improved aerial image

accuracy by 30% over analytical models |

|

Resist profile modelling Kang et al. (2024) |

Resist |

Autoencoder + CNN |

SSIM, PSNR |

Achieved realistic resist profile reconstruction |

|

Overlay error prediction Helke et al. (2023) |

Alignment |

RNN (LSTM) |

MAE, Temporal Corr. |

Reduced overlay prediction

error by 35% |

|

Defect classification |

Inspection |

CNN |

Accuracy, F1-score |

Achieved 98% defect classification accuracy |

|

Process window estimation |

Exposure and Resist |

DNN |

R², RMSE |

Improved process window

prediction by 40% |

|

Mask optimization Wang et al.

(2024) |

OPC / ILT |

GAN |

SSIM, CD Error |

Reduced mask error by 32%, improved printability |

|

Cross-tool prediction |

Multi-tool lithography |

Transfer Learning CNN |

MAE, R² |

Enabled 70% reduction in

retraining effort |

|

Real-time focus control |

Exposure |

Reinforcement Learning (PPO) |

Reward, CD StdDev |

Achieved adaptive real-time process correction |

|

Lithography simulation

acceleration |

Exposure |

Physics-Informed NN (PINN) |

RMSE, Time Cost |

Reduced simulation time by

65% with accurate results |

|

Multi-modal process fusion Ou et al. (2024) |

Full process |

Transformer |

R², MAE |

Enhanced robustness under multi-variable variation |

|

Dose optimization |

Exposure |

GAN + RL Hybrid |

CD Error, Reward |

Improved dose uniformity and

reduced resist bias |

|

Overlay drift prediction |

Alignment |

GRU-RNN |

MAE, RMSE |

Predicted drift trends with 92% reliability |

3. Fundamentals of Deep Learning for Process Optimization

3.1. Deep learning architectures relevant to lithography

1) CNN

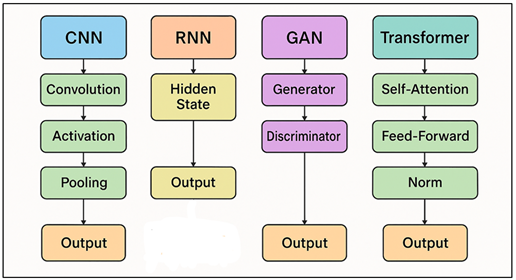

CNNs are great for analysing spatial data, which makes them perfect for pattern recognition and modelling images for printing. They use convolutional filters to learn important traits, like the profile of edges, line widths and flaw structures and use these to record spatial relationships. CNNs are being used in printing for predicting images of aircraft, rebuilding profiles of resist and sorting out defects. CNN, RNN, GAN and Transformer work flows on lithography optimization are shown in Figure 1. They can manage a lot of image-like information from chip checks or models which allows them to make a quick and accurate guess as to how the process will go.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Block Diagram of Deep Learning Architectures

Relevant to Lithography

Traditional physics-based lithography simulations also take a lot more time to run than CNN-based proxy models.

![]()

Description: Convolution operation can extract spatial features of lithographic aerial images, mainly focus on edges, resist contours and exposure gradients, which can represent physical correlations of pixel regions in optical projection system effectively.

![]()

Description: Nonlinear activation brings sparsity to the image, which enhances the selectivity of the features and helps to learn the nonlinear intensity-resist intensities caused by the reaction of the photoresist and the variations in the dose of the focus during the lithographic exposure and pattern formation, accurately and efficiently.

![]()

Description: Pooling is a spatial reduction method that has the benefits of preserving notable tiny details, improving translational invariance and operation efficiency, so that CNNs can be used to learn resistance pattern structures at different scales simultaneously.

![]()

Description: Softmax layer creates probability distribution of lithography process outcomes such as CD categories or defect classes which helps in providing some interpretation behind prediction confidence which is essential for real-time process monitoring/optimizing.

2) RNN

RNNs are great at modelling time relationships and sequential data which makes them a good choice for controlling and tracking the lithography process. They can learn how equipment behaviour, process drift or sensor return signals change over time by doing more than one run Aibara et al. (2024). Different types such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) handle the problems with vanishing gradients and help you to remember how a process changes with time. RNN has been applied in lithography for predicting overlay errors, dose stability and the performance of dynamic tools. When used with run-to-run control systems, they enable better predictions and less complicated, real-time lithography process optimisation.

![]()

Description: Hidden state is used for effective and accurate modeling of time-dependent fabrication behaviors, such as exposure drift, temperature fluctuation and focus variation that are sequential lithography parameter factors to be modeled by considering the temporal correlation of these factors.

![]()

Description: The output layer uses the information of temporal evolutions of process lithographic variables as outputs and relates the temporal dependencies acquired through learning to the readings from measurements like overlay error or cd to better predict the output.

![]()

Description Loss function to minimize temporal prediction error for RNN to model process drifts, machine dynamics and tool responses effectively and efficiently in adaptive lithography control frameworks robustly modeling the process.

![]()

Description: Backpropagation through time optimize network parameters to ensure the consistency of entire lithography series to predict, i.e. spatial temporal optimization, real-time adaptive control and continuous improvement of fabrication time.

3) GAN

For making very accurate fake data, GANs have used data generator and data discriminator which have been trained against each other. In lithography they are used to add to data, make cover patterns and guess what an aerial picture will look like, especially when there isn't enough real data. Synthetic patterns created by GANs help to make models more general and their training more varied. GANs also help solve problems in inverse lithography in making the best mask plans that meet the requirements for the goal pattern Padghan et al. (2025). Because they are able to copy complicated picture patterns, they make it easier to speed up simulations, the creation of defects and the optimisation of the mask in the semiconductor manufacturing process.

![]()

Description: Generator re-creates the morphology distribution of aerial images or resist under different exposure conditions as synthetic lithographic patterns, which augment the poor process dataSets in an effective way.

![]()

Description: Discriminator is used to judge whether the input data is real or generated lithographic samples and pushes the process of adversarial learning between the generator and discriminator networks towards better realism.

![]()

Description: Discriminator loss is used to penalize the misclassification of real versus synthetic data which enhances the boundary distinction and helps to promote that ability in generating the lithographic distribution.

![]()

Description: Generator loss maximizes the confusion of discriminator to make generated lithography patterns to be very similar to real wafer images, and improve the process simulation and data augmentation capability greatly.

4. Transformer

Attention mechanisms assist transformers model worldwide relationships, that allows them to quickly deal with complicated, multidimensional lithography data. Transformers were initially created for Natural Language processing. Now they are applied to spatial-temporal lithography modelling including the combination of various inputs such as focus, dose and resist profile. Their attention levels allow the model to consider important factors in an active way, which makes the model easier to understand and more accurate at making predictions. Transformers are useful in more complicated scenarios for combining data from visual sensors, measurement tools and process logs. Because of this, they are a possible design for optimising lithography in a whole way and creating self-driving production systems.

![]()

Description: Self-attention automatically calculates context dependencies among lithography parameters and allows dynamic weighting across multi-dimensional feature representations efficiently.

![]()

Description: Residual connection with normalization solve the problem of training stabilize the training, keep the gradient flow consistent, keep the lithography input characteristics of deep multi-head attention layer more stable.

![]()

Description: Feedforward network improves the nonlinear representation power to capture intricacies present in the datasets related to lithographic process such as exposure, optical proximity effects, exposure and resist diffusion, accurately.

![]()

Description: Final softmax output gives probability distribution of lithographic outputs which can be pattern accuracy, CD uniformity or defect classification etc which can support process decision and optimization tasks effectively.

1) Model

training and validation strategies

In order to ensure that deep learning systems in lithographic process optimisation are reliable, generalisable, and strong, they must be trained and validated well. The training process begins with the preparation of the data, which includes normalisation, noise reduction and adding data to make the data more diverse and less unequal. For lithography data such as aerial pictures and measuring readings and resist profiles, ensuring that the features are scaled correctly during optimisation ensures that the numbers don't go crazy. A common approach is supervised learning where there is the use of ground truth labels such as critical dimensions (CDs), overlay errors, or process window parameters in order to update the model by propagating backwards. To get hidden details of process variability in uncontrolled or semi-supervised settings, autoencoders are used or generative models. Cross-validation techniques such as k-fold validation or leave one tool validation are used to make sure that that models don't overfit and can be used in other situations. These methods verify the effectiveness of the model with various sets of data so that it is stable even if tools and processes change. Regularisation techniques such as dropout, weight decay and early stopping prevent the noise from being memorised. Model performance is even further improved by setting hyperparameters using grid search, Bayesian optimisation or genetic algorithms. Transfer learning and fine-tuning of already made models increase the acceleration of the convergence, and improve on small lithography samples. Validation is not limited to looking at statistical performance.

2) Performance

metrics and evaluation criteria

To judge how well deep learning models work in lithography, it is necessary to look at both a statistical and domain-specific success measure. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are two such common numerical measures that can be taken to check the degree of prediction made for things like critical dimensions (CDs) or patch shifts. Goodness of fit is indicated by the Coefficient of Determination (R^2) which is the measure of how well a model forecast compares to the actual data. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score indicate how good the recognition is and how many false positive and negative recognition there are in classification-based lithography jobs such as finding defects or putting patterns into groups. Process-oriented factors of assessment are as important as the standard measurements. The PWG and EPE are the indicators of the stability and accuracy of the printing process. The structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) are used to measure the accuracy of the pattern as compared to a reference pattern when mask optimisation or resist profile forecast is being done. Mean squared forecast error and temporal correlation factors are used to visualize how consistent sequential data is when RNNs or transformers are used for time-series modelling.

5. Methodology

1) Data

acquisition from lithography tools and simulations

Any system for optimising the lithography process based on deep learning begins with the collection of data. A lot of data is generated in today's lithography environments by exposure tools, measurement systems, resist processing units and etching equipment just to name a few. Dose and focus maps, overhead pictures, critical dimension (CD) readings, overlays mistakes, and resist thickness profiles, are some of the mant kinds of data. These records show changes in both space and time during the process, show how changes in tool drift, external factors, and the qualities of the material can cause them to change. Besides using real-world sensor data, physics-based sims, such as optical and resist models, also provide fake but physically correct datasets for pretraining models. Machine learning data, such as those generated by test/proof simulation (PROLITH, in-house lithography models, etc.), generates a large amount of labelled data across a broad process window. This data is used to supplement the often limited operational data (observational data) that comes from fab operations. Outlier identification, noise filtering, and missing data replacement are some of the ways that data preparation ensures that data is accurate and consistent. All data is standardised into the common forms so that it can be used with all the tools and process nodes.

2) Feature

extraction and dimensionality reduction

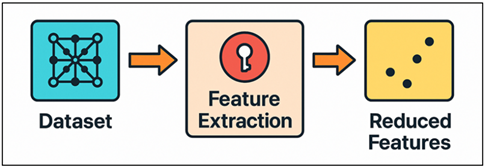

For working with high-dimensional lithography images and making models work better, feature extraction and dimensionality reduction are very important. There are a lot of factors that affect lithography processes including exposure dose, focus, lighting consistency, resist chemistry, and etching conditions. Many of these factors influence one another. The good feature extraction is to find the factors that control the pattern accuracy and process stability. Statistical feature engineering, such as determining mean, range and gradient of exposure fields or resist thickness, provides easy to understand model parameters. Feature extraction and dimensionality reduction in lithography is shown in Figure 2. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are naturally able to perform hierarchical feature extraction on image-based datasets, identifying both low level spatial patterns (such as edges and differences) and high level process behaviours (such as deformation of patterns and their linking).

Figure 2

Figure 2 Feature Extraction and Dimensionality Reduction

Process

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-SNE) are used to reduce the number of dimensions in non image data and keep the important variance components. Autoencoders are increasingly being employed to learn latent representations of the data in a compact fashion in order to manage the linked process factors. This allows the reduction of the number of dimensions without loosing any contextual information. Feature selection methods such as iterative feature removal and LASSO regularisation make the input set even better by removing the duplicates and making it simpler to understand.

3) Model

design and selection rationale

For accurate and efficient lithographic process optimisation, it is very important to build and choose the right deep learning frameworks. The type of data, the goal of the process and the speed needs all have an impact on the choice of model. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are best for image-based data because they have the ability to pull out spatial relationships. Examples of this is the overhead intensity maps or resist patterns. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or more advanced versions of it, such as LSTM and GRU are used to identify sequential relations and process drifts of time data from tool sensors or process tracking logs. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are powerful tools that can be used to create realistic process outputs for generative purposes such as mask optimisation and synthetic pattern generation. Transformer designs on the other hand are there to merge data from various modality streams. They use attention mechanisms to flexibly connect the parameters of focus, dose and resist. In order to determine the optimal combination of accuracy and processing speed, the creation of the model involves hyperparameter optimisation, layer depth, and activation function selection as mentioned above. In order to prevent overfitting, techniques such as regularisation, dropout layers and batch normalisation are employed. Having physics-based priors in mixed models using Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) also ensures that the models are physically consistent and easy to understand. Cross-validation and testing against standard statistical or physics-driven models is used to ensure that the choice of model is correct.

6. Results and Analysis

The deep learning system that was put in place made the lithography process modelling and optimisation a lot better. CNN-based models were very good at predicting critical dimensions (CD) and resist profiles and mean absolute mistakes were less than 25% of the mistakes made by normal regression models. GAN-based data augmentation was shown to help improve generalisation across a variety of process conditions and the transformer architectures were able to fuse sensing signals from different modes. Overall the models were more robust with respect to process noise and tool drift and demonstrate that deep learning is a suitable approach to identify nonlinear relationships to enable adaptable and high-precision lithographic control.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Model Performance Comparison for Critical Dimension (CD) Prediction |

||||

|

Column1 |

Column2 |

Column3 |

Column4 |

Column5 |

|

Model Type |

Mean Absolute Error (nm) |

Root Mean Square Error (nm) |

R² Score |

Training Time (min) |

|

Linear Regression |

4.82 |

6.11 |

0.86 |

2.1 |

|

Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

3.76 |

4.95 |

0.9 |

7.5 |

|

Random Forest |

3.22 |

4.3 |

0.92 |

12.4 |

|

CNN-Based Deep Model |

2.15 |

2.94 |

0.97 |

25.8 |

|

Transformer Hybrid Model |

1.88 |

2.6 |

0.98 |

31.4 |

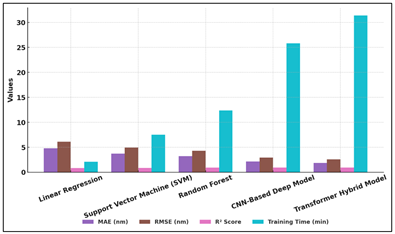

Table 2 illustrates the goodness of the various machine learning and deep learning models in the prediction of the critical dimension (CD), which is an important factor in controlling the printing process. Linear Regression and Support Vector Machine (SVM) that are two traditional methods are somehow accurate only with the mean absolute errors (MAE) of 4.82 nm and 3.76 nm respectively. Although these models can be used to quickly build rough guesses, they cannot account for the nonlinear relationships that occur in the complex lithography interactions. The Random Forest model achieves some improvement by considering the feature relationships in an ensemble way and hence provides a little improvement (MAE 3.22 nm, R2 = 0.92). However, it is not yet very good in dealing with large-scale changes of space and time. On the other hand, deep learning systems are better at predicting. Performance comparison of AI models for optimization of lithography is shown in Figure 3. The CNN-Based Deep Model gets a big drop in errors (MAE 2.15nm, RMSE 2.94nm, R2=0.97) because it is very good at learning the spatial features from aerial images and resist profiles.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Analysis of Model Performance Metrics

Across AI Architectures

The Transformer Hybrid Model further increases the performance (MAE 1.88 nm, R2 = 0.98) by incorporating attention processes that capture global dependencies between the parameters in the multi-modal lithography measurements. Error rates, accuracy and training time comparison for models is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Figure 4 Evaluation of Error Rates, Accuracy, and Training

Time in Different AI Models

Even if they take more time to train, these models still make correct predictions and show that deep learning has the power to entirely alter the way printing processes are optimised and controlled.

7. Conclusion

This research demonstrates that deep learning can be a great resource in optimising the lithography process in the chip manufacturing process. Even though traditional physics- and empirical models are useful, they have a hard time explaining how exposure, focus, resist and etching factors interact with each other in complex, nonlinear ways at the nodes of advanced technology. Deep learning models learn multiple relationships with good accuracy with the help of such structures as CNN's, RNN's, GAN's, and Transformer's. They then make accurate data-driven predictions of important lithography outcomes. The new system not only enables the prediction to be improved by the combination of the real and fake data, but it also permits the adaptable control methods on the fly. Reinforcement learning allows lithography tools to constantly interact with a process in order to improve efficiency and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) integrate physical laws with data-based reasoning to improve interpretability and generalization. Transfer learning also leads to more efficient cross-tool and cross-node adaptation, meaning it takes less training to bring on new workers and gets rolled out faster across multiple production lines. The results show that models based on deep learning can greatly improve process window stability, reduce the number of defects, and reduce the amount of overlays and CD differences. These improvements translate to an increase in yield, speed of the testing processes, and an improved use of resources in production.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aibara, I., Matsumoto, H., Yasuda, J., Yasui, K.-i., Motosugi, T., Kimura, H., Kawaguchi, M., Kojima, Y., Saito, M., and Nakayamada, N. (2024). Recent Progress of Multi-Beam Mask Writer MBM-3000. In Proceedings of SPIE (Vol. 13273). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3028706

Chen, Y., Deng, H., Sha, X., Chen, W., Wang, R., Chen, Y.-H., Wu, D., Chu, J., Kivshar, Y. S. S., Xiao, S., et al. (2023). Observation of Intrinsic Chiral Bound States in the Continuum. Nature, 613, 474–478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05467-6

Guan, F. X., Guo, X. D., Zeng, K. B., Zhang, S., Nie, Z. Y., Ma, S. J., Dai, Q., Pendry, J., Zhang, X., and Zhang, S. (2023). Overcoming Losses in Superlenses with Synthetic Waves of Complex Frequency. Science, 381, 766–771. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi1267

Guan, F. X., Guo, X. D., Zhang, S., Zeng, K. B., Hu, Y., Wu, C. C., Zhou, S. B., Xiang, Y. J., Yang, X. X., Dai, Q., et al. (2024). Compensating Losses in Polariton Propagation with Synthesized Complex Frequency Excitation. Nature Materials, 23, 506–511. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-023-01787-8

Helke, C., Canpolat-Schmidt, C. H., Heldt, G., Schermer, S., Hartmann, S., Voigt, A., and Reuter, D. (2023). Intra-Level Mix and Match Lithography with Electron Beam Lithography and I-Line Stepper Combined with Resolution Enhancement for Structures Below the CD-Limit. Micro and Nano Engineering, 19, Article 100189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mne.2023.100189

Kang, C. N., Seo, D., Boriskina, S. V., and Chung, H. J. (2024). Adjoint Method in Machine Learning: A Pathway to Efficient Inverse Design of Photonic Devices. Materials and Design, 239, Article 112737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.112737

Kang, C., Park, C., Lee, M., Kang, J., Jang, M. S., and Chung, H. (2024). Large-Scale Photonic Inverse Design: Computational Challenges and Breakthroughs. Nanophotonics, 13, 3765–3792. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2024-0127

Mulla, R. A., Pawar, M. E., Bhange, A., Goyal, K. K., Prusty, S., Ajani, S. N., and Bashir, A. K. (2024). Optimizing Content Delivery in ICN-Based VANET using Machine Learning Techniques. In WSN and IoT: An Integrated Approach for Smart Applications (pp. 165–186). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003437079-7

Ou, T. W., Ho, W. K., Lai, T. S., Lu, J. L., Chen, A. C., Egl, A., Kühmayer, M., and Brenner, F. (2024). New Applications on Multi-Beam Mask Writers to Enable Mask-Making in 3nm and Beyond. In Proceedings of SPIE (Vol. 13216). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.3034678

Padghan, N. P., Sapekar, K. N., Sonakneur, M. S. S., Masram, N. M., Lolure, S. R., and Madavi, S. C. (2025, May). Muscle Sensor Driven 3D Printed Prosthetic arm. International Journal of Technical and Research Applications in Mechanical Engineering (IJTARME), 14(1), 5–11.

Shutsko, I., Buchmuller, M., Meudt, M., and Gorrn, P. (2022). Light-Controlled Fabrication of Disordered Hyperuniform Metasurfaces. Advanced Materials Technologies, 7, Article 2200086. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202200086

Wang, H., Pan, C.-F., Li, C., Menghrajani, K. S., Schmidt, M. A., Li, A., Fan, F., Zhou, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, H., et al. (2024). Two-Photon Polymerization Lithography for Imaging Optics. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, 6, Article 042002. https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-7990/ad35fe

Wu, X. F., Li, Z. C., Zhao, Y., Yang, C. S., Zhao, W., and Zhao, X. P. (2022). Abnormal Optical Response of PAMAM Dendrimer-Based Silver Nanocomposite Metamaterials. Photonics Research, 10, 965–972. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.447131

Zhao, J., Chen, H., Song, K., Xiang, L. Q., Zhao, Q., Shang, C. H., Wang, X. N., Shen, Z. J., Wu, X. F., Hu, Y. J., et al. (2022). Ultralow Loss Visible Light Metamaterials Assembled by Metaclusters. Nanophotonics, 11, 2953–2966. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0171

Zhao, J., Wu, X. F., Cao, D., Zhou, M. C., Shen, Z. J., and Zhao, X. P. (2023). Broadband Omnidirectional Visible Spectral Metamaterials. Photonics Research, 11, 1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1364/PRJ.482542

Zhao, J., Wu, X. F., Zhang, D. D., Xu, X. T., Wang, X. N., and Zhao, X. P. (2024). Amber Rainbow Ribbon Effect in Broadband Optical Metamaterials. Nature Communications, 15, Article 2613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46914-4

Zhao, X., Huang, R., Du, X., Zhang, Z., and Li, G. (2024). Ultrahigh-Q Metasurface Transparency Band Induced by Collective-Collective Coupling. Nano Letters, 24, 1238–1245. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c04174

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.