ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Neural Networks for Texture Simulation in Prints

Manish Chaudhary 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Taranath N L 2

,

Dr. Taranath N L 2![]()

![]() , Jaskirat Singh 3

, Jaskirat Singh 3![]()

![]() , Mona Sharma 4

, Mona Sharma 4![]() , Ashu Katyal 4

, Ashu Katyal 4![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Shashikant Patil 6

,

Dr. Shashikant Patil 6![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering (AI), Noida Institute

of Engineering and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Presidency

University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

3 Centre of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura,

Punjab, India

4 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida International

University, Greater Nodia, India

5 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

6 Professor, UGDX School of Technology, ATLAS Skill Tech University,

Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Computer

images, material science and additive manufacturing are all important fields

of study, which work together to study texture simulation in printed

materials. The fine-grained reality and variety of real-world materials is

difficult to represent using traditional texture creation methods based on

procedural algorithms and physical modelling. This research explores the use

of neural networks to simulate the textures in prints. The main focus of the

book is convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial

networks (GANs). The suggested method attempts to rightfully recreate the

feel and look of textures in order to make digital and physical results look

and feel more like the real thing. The study begins with the collection of

structured data about various textures of prints. Next cleaning techniques

such as normalisation, patch extraction and

addition are applied to improve generalisation of

the model. For extracting hierarchy features, CNN based model is used. A GAN

design generates new images by learning the hidden patterns of the surfaces

of materials. To locate the right combination between image sharpness and

reality, training methods have loss function tuning, flexible learning rate

plans, and aggressive optimisation. This system can

be used for 3D printing, digital manufacture and virtual modelling, all of

which benefit from being able to represent the correct materials for better

results in terms of looks as well as functionality. |

|||

|

Received 26 January 2025 Accepted 21 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Manish

Chaudhary, manishchaudhary@niet.co.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6632 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Neural Networks, Texture Synthesis, Printing

Technology, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Generative Adversarial

Networks (GAN), Material Visualization |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Today, printing, computer manufacture, and graphic design are all dependent on being able to accurately simulate surface appearance. As businesses use more digital tools to display how their products will look and feel, there has been a greater need for more true visual and felt texture representation. When it comes to 3D printing, packing, or artistic copying, being able to successfully copy the textures of things like metal, cloth, stone, wood, or metal, will decide not only how they look, but also how well they work and how well they are thought of as quality. Texture modelling methods that are based on procedural methods, physical math, or handmade features don't always do a good job of catching the random patterns, flaws and complex shapes that make up real world surfaces. Because of this, there has been a move towards data-based and learning-based methodologies that are able to capture the natural variety and variability of the way things look. Pattern recognition and image creation has changed a have due to recent advancement in Machine learning particularly Neural network. Hierarchical feature models are learned very well by neural networks Khaki et al. (2021) from big datasets. This makes them perfect for the analysis and creation of textures. These include generative adversarial networks (GANs) which are very good at making new textures that look real and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) which are very good at finding spatial connections and repeating patterns.

These designs allow creating images that not only resemble real materials but change according to the lighting, the perspective and the scale. This is extremely important for printing simulation which needs to be realistic. The addition of texture modelling has the ability to completely change printing technology especially digital and 3D printing Ding et al. (2020). By using neural networks it is now possible to copy surface details straight from data samples which gets around the problems that come with designing things by hand or using simple texture mapping. This makes printed materials look and feel more like real things, which results in better colour accuracy, more design options and better physical quality Park et al. (2021). As an example, in additive manufacturing, lifelike surface modelling can help find the best ways of using layer layering to make the material look either rough or shiny. Neural networks can be used to make complex patterns for artistic prints, packing, and visual effects in the field of graphic arts without a lot of human input.

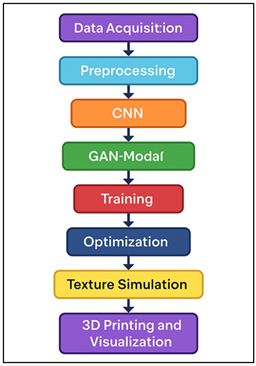

Figure 1

Figure 1 Workflow of Neural Network-Based Texture Simulation in Printing

Also, neural network-based material modelling makes it possible to show things, both virtually and physically. Figure 1 depicts the sequential neural processes in the generation of realistic print texture. High-fidelity texture models can now be added to the digital twin, a virtual copy of a real thing. These models are accurate predictors of appearance of materials when printed. Not only is this good for testing and visualizing, it is also making manufacturing more sustainable by reducing waste and errors. Neural networks can even be used to make guesses on how to change the printing parameters to influence the material results, which is helpful for process improvement in the manufacturing sector Zhang et al. (2022). Even though neural networks have a lot of potential, they are hard to use in the modelling of materials. It can be difficult to access quality information, especially for some print materials and circumstances. Because deep networks are so complicated to compute, they require great tools and methods that are optimised to perform in real time or very near to real time. Another topic of current study is ensuring that synthesised images remain identical when resized or mixed on various forms of print. Still, the combining of machine learning and printing technology is a big step towards smart material design O’Connell et al. (2021). By modelling things with neural networks, scientists and engineers are able to look beyond visual copy and develop realistic simulations of materials. These will have texture, and depth, and the ability to feel things through touch that are the same in the digital as in the printed.

2. Literature Review

1) Overview

of existing texture generation techniques

Making textures had been an important part of computer images, printing and showing what materials look like for a long time. There are three main types of traditional methods for making textures: random methods, exemplar-based synthesis and physically based modelling. Natural surfaces are created in procedural image generation through mathematical functions, such as Perlin noise, fractals, or turbulence Jang et al. (2020). Procedural methods are fast, parametric and run on a computer but are sometimes not as rough and deep as real-world patterns, which means they are not as effective for simulating a high fidelity print. Exemplar-based synthesis was developed to get around these problems based upon looking at sample pictures and copying their material patterns. Non-parametric sampling and patch-based synthesis are two algorithms that take small areas of texture and copy them on a new surface while maintaining the cohesion and visual likeness of the texture Zhang et al. (2024). But due to the dependence on statistical aspects of the source image, these methods are not very good at handling nonstationary backgrounds or instances requiring changes in structure.

2) Machine

learning approaches to texture synthesis

Machine learning has altered the game when it comes to texture generation by allowing computers to learn and replicate complex things from the data they have. Early methods used statistical learning and grouping and to describe patterns, they used things like Gabor filters, wavelet coefficients or gray-level co-occurrence matrices (GLCM). Even if these hand-made features allowed models to interpret spatial relations and frequency components, they were not very good in representing texture types Martini et al. (2024). With the advent of deep learning, the creation of images has become much more powerful. Some of the first to discover hierarchical representations of texture in hidden feature spaces by encoding both local and global structure were the deep belief networks and autoencoders. This improvement made it possible to create or rebuild images from learnt compressed embeddings as opposed to directly changing pixels. Recently, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have become very popular since they are good at modelling spatial orders. CNN-based texture creation is a method in which convolutional filters are used to find patterns at different sizes, this allows you to rebuild and change things in a realistic way Rani et al. (2024). Gatys et al. introduced neural style transfer, which demonstrated that neural convolutional networks could display the texture information in the form of neural CNN feature maps, producing both rich and logical looking outputs.

3) Neural

network architectures applied in printing and graphics

In the past, neural networks were only applied to simple pattern recognition. Now, they are applied for more complex dynamic modelling. Because they have the ability to pull out hierarchical spatial features, convolution neural networks (CNNs) are one of the most popular designs for jobs that involve textures. CNNs have been used in printing to enhance images, correct colours and classify textures into groups. This allows fine grained surface features to be automatically identified and simulated. They are excellent for the texture analysis and high-resolution surface generation due to their capability to work on local and global relations. Generative Adversarial Networks Abubakr et al. (2020) or GANs are a big step forward in the field of images pattern creation. The structures of GANs consist of two competing networks, one of which is called a generator and the other one being a discriminator. They use adversarial learning to increase accuracy of images over time. This design has been shown to work well for the creation of a wide range of textures, which appear to be realistic and believable Ekatpure et al. (2025). To this structure, conditional GANs (cGANs) add the ability to vary certain aspects of the texture, such as its colour, roughness, or reflectivity. This makes them useful in the flexible printing and design tasks. The comparative studies on the advancements in neural texture simulation is shown in the Table 1. Different types of topologies, like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Transformer-based models have been examined to discover a way to display linear, or environmental, connections in texture generation.

Table 1

|

Table

1 Summary of Related Work on Texture Simulation

Using Neural Networks |

|||||

|

Neural Style Transfer |

Natural images |

CNN (VGG-19) |

Artistic texture synthesis |

Gram Matrix Similarity |

Limited control over texture scale |

|

Texture Networks Zhou et al. (2024) |

Image datasets |

Feed-forward CNN |

Real-time texture generation |

SSIM, Inception Score |

Limited texture diversity |

|

CNN Feature Optimization |

Object textures |

CNN Encoder-Decoder |

Texture reconstruction |

L2 Loss |

Computationally expensive |

|

Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) |

ImageNet |

GAN |

General image generation |

FID, IS |

Struggles with fine texture detail |

|

Conditional GAN for Materials |

Material textures |

cGAN |

Material rendering and printing |

PSNR, SSIM |

Requires large labeled

datasets |

|

Multi-scale Texture GAN Rehman et al. (2024) |

3D surface data |

GAN + Multi-scale CNN |

3D printing simulation |

FID, Perceptual Score |

High computational cost |

|

Hybrid CNN–GAN |

Textile images |

CNN + GAN Hybrid |

Fabric print simulation |

SSIM, MSE |

Training instability observed |

|

Physics-informed CNN Bohušík et al. (2023) |

Reflective surfaces |

CNN |

Printing process modeling |

RMSE, BRDF Error |

Complex calibration process |

|

3D Texture Autoencoder |

3D scanned textures |

Autoencoder |

Additive manufacturing |

PSNR, Structural Index |

Limited generalization |

|

CycleGAN for Texture

Translation |

Cross-material textures |

CycleGAN |

Digital fabrication |

FID, User Rating |

Artifacts in large texture regions |

|

Neural Texture Simulation |

Print texture dataset |

CNN + GAN |

Printing and visualization |

SSIM, FID, PSNR |

Needs larger multimodal datasets |

3. Methodology

1) Data

acquisition and preprocessing of print textures

A neural network based material modelling system is only as good as its collection, which comprises different types of data. To generate data for print textures, it's necessary to conduct high-resolution photographs or scans of printed substrates that have been created using a wide variety of different materials, print methods and lighting conditions. This applies to paper, plastic, metal and fabric materials as well as patterns created with inkjet, laser and 3D printers. For the neural network to be able to learn important patterns about surface reflection, gloss, grain and depth, each texture sample needs to correctly display both visual and physical characteristics. Standardised image settings are being used to make sure that all is the same. These display systems typically have controlled lighting and measured colour profiles. Raw data is processed through a series of steps in order to prepare it for the model training. Usually, the first steps in the preprocessing are normalisation (changing the brightness and colour balance of the image), cropping and patch extraction (splitting textures into smaller and more uniform areas), and augmentation (changing the variability of a dataset in a fake way, for example rotating, scaling, flipping the images, or changing the contrast).

2) Neural

network model design

CNN

Being so good at capturing spatial structures in pictures, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are the basis for analysing and creating print effects. A CNN consists of a number of layers including convolutional, pooling layers and fully connected layers. These layers acquire features over time from very simple lines to complex texture structure. In the case of texture modelling, the convolutional filters of CNN learn small features such as grain, roughness and micro-patterns. Then, lower layers combine these into bigger patterns which display how the surface is more generally shaped. CNNs can be taught to sort or divide texture areas, guess type of material, as well as put together high-resolution texture maps for print texture analysis. When CNN feature maps is utilized for synthesis, it will make accurate textures by transferring the learnt patterns on new surfaces. This is similar to how the texture-based style transfer methods work. This process is made better by advanced designs like U-Net and ResNet which keep small details and make spread of features better through skip links and residues learning.

·

Step 1: Input Representation

Let the input texture image be represented as a tensor:

![]()

where H, W, C denote the image height, width, and number of channels, respectively.

·

Step 2: Convolution Operation

Each convolutional layer applies a kernel K to the input feature map:

![]()

where F_ij^(l) is the activation of neuron (i,j) in layer l, and b^(l) is the bias term.

·

Step 3: Nonlinear Activation

To introduce nonlinearity, the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is applied:

![]()

·

Step 4: Pooling Operation

Pooling reduces spatial dimensions while preserving key texture features:

![]()

where R_ij represents the local pooling region.

·

Step 5: Feature Flattening

The extracted features are flattened into a 1D vector for further processing:

![]()

where L is the last convolutional layer.

·

Step 6: Fully Connected Layer

A dense layer integrates global texture features:

![]()

where f is a nonlinear activation function

GAN

Innovative Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have changed the way pictures are made by allowing people to make new and very realistic surfaces that look and feel like genuine materials. For GAN, it consisted of 2 neural networks, generator and discriminator, that play a minimax game. The discriminator is used to check real samples to see how real those images are that have been produced by the generator. The generator is trained iteratively and sees the output which is indistinguishable from real textures. This produces high fidelity surface pattern changes which occur naturally. In the case of print texture modelling, GANs can be used to model both how something looks and how it feels, which can be used to create new patterns or improve on old patterns.

·

Step 1: Input Noise Vector

A random latent vector is sampled from a prior distribution:

![]()

·

Step 2: Generator Mapping

The generator transforms z into a synthetic texture image:

![]()

where θ_G are generator parameters.

·

Step 3: Discriminator Evaluation

The discriminator predicts whether an input image is real or generated:

![]()

where σ is the sigmoid function, and θ_D are discriminator parameters.

·

Step 4: Adversarial Objective Function

The min–max optimization problem is formulated as:

![]()

·

Step 5: Generator Loss

To fool the discriminator, the generator minimizes:

![]()

·

Step 6: Discriminator Loss

The discriminator maximizes classification accuracy:

![]()

·

Step 7: Parameter Optimization

Both networks are trained alternately using gradient descent:

![]()

![]()

where η is the learning rate.

Through this adversarial process, the generator learns to synthesize visually convincing and statistically consistent print textures, surpassing traditional methods in realism and diversity.

3) Training

and optimization strategies

A good balance between data quality, model complexity and processing speed needs to be found when training and optimizing neural networks for texture simulation. To ensure that the model is able to work well across datasets and not overfit, samples of the texture are typically divided into training, validation, and testing datasets at the beginning of the process. When the model is being trained, patches of textures are fed into the model and its projected outputs are compared with real images by using special loss functions. Mean Squared Error (MSE) and perceived loss are two examples of popular types of losses for CNNs. These are based on deep feature representations rather than pixel-level accuracy, which measures visual similarity. GANs on the other hand use an adversarial loss, in which the generator learns to minimise its mistake in response to input from a discriminator. This results in the development of more realistic patterns. However, gradient-based learning algorithms (such as Adam or RMSprop), which adaptively vary learning rates to accelerate convergence, are very important for optimisation.

4. Applications and Implications

1) Use

in 3D printing and digital fabrication

The use of neural networks for simulating textures in 3D printing and digital manufacturing has resulted in a change in the way surfaces and materials are displayed and produced. Texture is an important factor on 3D printing because not only does it define how an object will appear but also how it will function, such as how it will handle pressure, the way it will reflect light and the tactility of the part. CNNs and GANs in particular make it possible to generate high fidelity surface patterns automatically, and then directly put on 3D models. These models are able to guess and make patterns of layers that appear to be the same as natural materials using real-world texture information. This makes the models more realistic, and increase the strength of the structures they use.

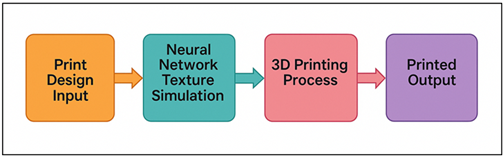

Figure 2

Figure 2 Process Flow of Neural Network-Based 3D Printing System

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow of the neural system linking the simulation of texture with 3D printing. This way, a lot of work that has to be done by hand in the planning process is reduced and printing is faster and more consistent.

2) Enhancement

of material design and visualization

Due to their ability to properly capture and copy complicated surface properties, neural networks have become useful tools in aspiration for better material design and visualisation. In the past, the approach to material design was to make a model, usually of the material by hand and test in the real world, which was time-consuming and not always accurate. Deep feature learning is a process in neural networks that automates the process of finding relationships between the composition of an object, its surface roughness, and its appearance. With this feature, digital materials can be made that have qualities like shine, roughness, transparency or reflection that are similar to those in the real world. When it comes to visualisation, CNNs and GANs assist in making things look more realistic when viewed in different light in situations. Before going ahead with production, designers can virtually test how different textures react to different sources and angles of the light. For instance, GAN-based systems can make it appear that the finish on a piece of leather, wood, or metal is real, which enables industrial designers, builders, and makers to get accurate models.

3) Industrial

and artistic applications

There are many areas in commercial and artistic graphics which employ neural networks for texture modelling. This is a combination of using new technology with creative expression. In the case of industrial manufacturing, however, neural models make it easier to accurately copy surfaces more easily in things like printed electronics, packing, car paint, and building materials. Industries can gain uniform product finishing while reducing the amount of material that is wasted by modelling micro-textures that alter the appearance or feel of things. Texture modelling is employed in the textile and fashion industries for digitally testing the weave and prints of cloth. This reduces the number of prototypes that must be made, as well as the cost of production. Neuronal networks have opened new avenues for being creative in the arts. Generative models assist artists and designers to produce patterns and shapes to be one-of-a-kind and don't conform to any rules of human design.

5. Results and Discussion

The suggested neural network models, CNN and GAN were very good at modelling accurate print patterns. The CNN model performed a good job of capturing small surface patterns and local texture structures while the GAN generated new texture which were more natural and made sense to the human eye. Quantitative tests using the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) and Frerech inception distance (FID) revealed that these were more accurate and had more variety as compared to old ones.

Table 2

|

Table

2 Quantitative Evaluation of Texture Simulation

Models |

||||

|

Model |

SSIM (↑) |

PSNR (dB) (↑) |

FID Score (↓) |

Training Time (hrs) |

|

Traditional Patch-Based |

0.71 |

22.5 |

74.3 |

1.2 |

|

CNN-Based Model |

0.89 |

29.8 |

41.7 |

4.8 |

|

GAN-Based Model |

0.93 |

31.2 |

28.9 |

6.5 |

|

Hybrid CNN–GAN |

0.95 |

32.7 |

21.5 |

7.1 |

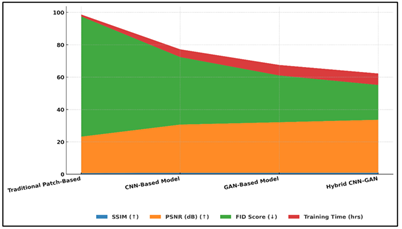

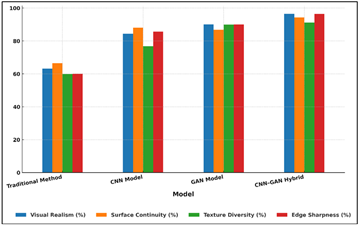

We can see the four texture simulation models in terms of their structural similarity (SSIM), peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), Frereit inception distance (FID) and training time in Table 2. Figure 3 presents performance comparison of AI models in texture generation.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Comparative Performance Metrics Across AI Image Generation Models

The standard patch-based method had the lowest SSIM (0.71) and PSNR (22.5 dB), which means it was not that good at preserving image structure and clarity. With an SSIM value of 0.89 and a PSNR of 29.8 dB, the model using CNN significantly improved the accuracy of reconstruction, indicating that it is good to learn hierarchical texture features.

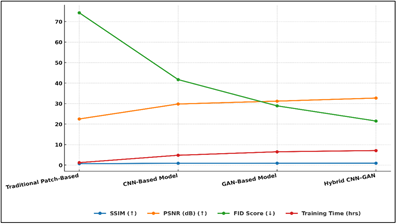

Figure 4

Figure 4 Trends in Image Quality and Efficiency Metrics for

AI Models

The model based on GAN has improved visual reality even further and as a result of using the GAN model, they could achieve a reduced FID score of 28.9 and could demonstrate a better perceived quality and a wider range of patterns produced. Figure 4 shows improving improvements in the quality and efficiency of AI images. The model with the best results was the mixed CNN-GAN model. It had the highest SSIM (0.95) and PSNR (32.7 dB), also the lowest FID (21.5), which means that it had the most realistic and accurate textures. The blend model had the best of accuracy, realism and computational speed for texture modelling, although it took a little longer to train (7.1 hours).

Table 3

|

Table 3 Subjective Evaluation – Texture Realism and Visual Coherence |

||||

|

Model |

Visual Realism (%) |

Surface Continuity (%) |

Texture Diversity (%) |

Edge Sharpness (%) |

|

Traditional Method |

63.2 |

66.5 |

59.9 |

60.1 |

|

CNN Model |

84.4 |

8.1 |

76.8 |

85.6 |

|

GAN Model |

90.1 |

86.8 |

89.9 |

90 |

|

CNN–GAN Hybrid |

96.5 |

94.3 |

91.2 |

96.4 |

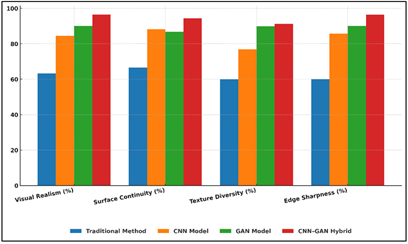

Table 3 illustrates how people rate texture simulation models as a result of four factors affecting the appearance of realism: surface consistency, texture variety and edge sharpness. The standard method scored worst, with 63.2% being found to have poor visual reality and 59.9% being found to have poor texture variety.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Comparison of Visual Quality Metrics Across Image Generation Models

This indicates that it has not been very successful at reproducing natural texture variations and smooth surfaces. Comparative results of visual quality performance of different image generation models can be seen in Figure 5. The CNN model did much better, especially in edge sharpness (85.6%) and visual reality (84.4%). This is because it could grasp features of fine material and local spatial structure. But its surface regularity (described as 80.1%) was slightly off - displaying some border artefacts in the rebuilt patterns. The GAN model had a better perceived performance with high scores in all parameters, particularly for material diversity (89.9%) and visual reality (90.1%).

Figure 6

Figure 6 Progressive Improvement of Visual Attributes from

Traditional to Hybrid Models

This is because it uses generative learning which adds natural randomness to make the model learn. Figure 6 illustrates progressive improvement of visual attributes from traditional to the hybrid model. The total results of CNN-GAN mix were the highest, with 96.5% visual realism and 96.4% edge sharpness. It made graphics that are continuous, consistent and very lifelike like the print surfaces in real life.

6. Conclusion

One part of this study looked at how neural networks can be used to simulate textures in printing. It was dedicated to how Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can give surfaces the appearance and sensation of reality. The research indicated that deep learning systems can effectively learn texture hierarchies, document material flaws and synthesise the print textures that are real, using organised data collection, cleaning and model training. CNNs were great at getting features from hierarchies and GANs brought in natural randomness and high visual realism that compensated for the bane of procedural and exemplar-based methods. When these models are utilized in printing and making things, big steps forward are made possible. Neural texture modelling allows better appearance and feel of the 3D printed object while reducing the complexity of the design and reducing the amount of waste left over. The benefit in the digital design of industrial products and product design is that you can quickly visualize a material in real life to make faster testing and well-informed decisions. These models can be used in the business and artistic world too to come up with new patterns, enhance the appearance of products and build brands. Problems such as lack of image collections, high processing cost, and the difference between the digital and real result have to be overcome. In the future, people should work on developing physics-based, mixed learning methods that consider the features of the materials, how the printers work, and how the lighting affects them. To make generalisation even stronger, lightweight designs should be optimised for real-time drawing, and datasets increased to include more materials.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abubakr, M., Abbas, A. T., Tomaz, I., Soliman, M. S., Luqman, M., and Hegab, H. (2020). Sustainable and Smart Manufacturing: An Integrated Approach. Sustainability, 12, Article 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062280

Bohušík, M., Stenchlák, V., Císar, M., Bulej, V., Kuric, I., Dodok, T., and Bencel, A. (2023). Mechatronic Device Control by Artificial Intelligence. Sensors, 23, Article 5872. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23135872

Ding, S., Wan, M. P., and Ng, B. F. (2020). Dynamic Analysis of Particle Emissions from FDM 3D Printers Through a Comparative Study of Chamber and Flow Tunnel Measurements. Environmental Science and Technology, 54, 14568–14577. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05309

Ekatpure, M. J. N., Asabe, T., Gaikwad, R., and Nagare, N. (2025). Exploration of EduQuest—An AI-Powered System for Question Generation and Test Automation. International Journal of Research in Advanced Engineering and Technology (IJRAET), 14(2), 42–45.

Jang, J., Ko, K., Kim, S., Kim, K., and Song, J. (2020). A Review of 3D Printing Technologies for Industrial Applications. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2020, Article 6018401.

Khaki, S., Duffy, E., Smetaon, A. F., and Morrin, A. (2021). Monitoring of Particulate Matter Emissions from 3D Printing Activity in the Home Setting. Sensors, 21, Article 3247. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21093247

Martini, B., Bellisario, D., and Coletti, P. (2024). Human-Centered and Sustainable Artificial Intelligence in Industry 5.0: Challenges and Perspectives. Sustainability, 16, Article 5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135448

O’Connell, S., Smith, G., Jonnalagadda, S., and Wensel, S. (2021). The use and Applications of 3D Printing Materials: A Survey. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 64, 431–442.

Park, J., Kwon, O. H., Yoon, C., and Park, M. (2021). Estimates of Particulate Matter Inhalation Doses During Three-Dimensional Printing: How Many Particles Can Penetrate Into Our Body? Indoor Air, 31, 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12736

Rani, S., Jining, D., Shoukat, K., Shoukat, M. U., and Nawaz, S. A. (2024). A Human–Machine Interaction Mechanism: Additive Manufacturing for Industry 5.0—Design and Management. Sustainability, 16, Article 4158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104158

Rehman, S. U., Riaz, R. D., Usman, M., and Kim, I.-H. (2024). Augmented Data-Driven Approach Towards 3D Printed Concrete Mix Prediction. Applied Sciences, 14, Article 7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14167231

Zhang, J., Chen, D. R., and Chen, S. C. (2022). A Review of Emission Characteristics and Control Strategies for Particles Emitted from 3D Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printing. Building and Environment, 221, Article 109348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109348

Zhang, Q., Zhou, Y., and Zou, S. (2024). Convergence guarantees for RMSProp and Adam in Generalized-Smooth Non-Convex Optimization with Affine Noise Variance. arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.01436

Zhou, L., Miller, J., Vezza, J., Mayster, M., Raffay, M., Justice, Q., Al Tamimi, Z., Hansotte, G., Sunkara, L. D., and Bernat, J. (2024). Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors, 24, Article 2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24092668

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.