ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Exploring GANs in Digital Media Education

Rahul Thakur 1![]()

![]() ,

Dr. Sonia Munjal 2

,

Dr. Sonia Munjal 2![]()

![]() , Abhinav Mishra 3

, Abhinav Mishra 3![]()

![]() , Dr. Ankita Gandhi 4

, Dr. Ankita Gandhi 4![]()

![]() , Mohit Malik 5

, Mohit Malik 5![]() , Dr. Zuleika Homavazir 6

, Dr. Zuleika Homavazir 6![]()

![]()

1 Centre

of Research Impact and Outcome, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, India

2 Professor,

Department of Master of Business Administration, Noida Institute of Engineering

and Technology, Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

3 Chitkara Centre for Research and Development, Chitkara University,

Himachal Pradesh, Solan, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Computer science and Engineering,

Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Parul institute of Engineering and

Technology, Parul University, Vadodara, Gujarat, India

5 Assistant Professor, School of Business Management, Noida

international University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

6 Professor, ISME - School of Management and Entrepreneurship, ATLAS

Skill Tech University, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The Generative

Adversarial Networks (GANs) introduced to the education of digital media can

be regarded as a significant change in the point of intersection of

creativity, computation, and ethics in educational context. The creative

tools and the educational model of both the use of GANs will be discussed in

the paper in terms of pedagogical and cognitive implications. The research

employed a mixed-methodology in three institutions, such as design, technical

and vocational setting, to determine the effect of the changes on the student

creativity, technical aptitude and the moral cognizance. The quantitative

findings demonstrated the existence of considerable improvements in the

knowledge of neural structures, model training and data interpretation, but a

substantial disparity was observed between the average scores concerning

proficiency abilities following the exposure to GAN-based modules. The

qualitative findings indicated that the level of engagement increased in the

learners and it presupposed the iterative workflows that were co-creative and

led to the mix of the human and machine creativity. Moreover, the ethical way

of thinking could be developed, which allowed deepfakes, data bias,

intellectual property concerns to become more aware and responsible digital

creators were created through the assistance of GANs. The GAN-based education

would promote creative autonomy and reflective judgment, which will be

requested of future professionals working in the creativity industries that

will be automated with AI by putting them in the position of being

co-creators with AI. The article recommends the systematic pedagogical plan

to integrate tools associated with GAN, project-based learning, and ethics

courses to produce sustainable and inclusive creative courses. Lastly, the

paper will present GANs as a revolutionary piece of technology, but also as

something that would revolutionize the creative way of teaching in the 21st

century as they would produce a pool of AI-sensitive creators who would be

morally aware. |

|||

|

Received 11 January 2025 Accepted 04 April 2025 Published 10 December 2025 Corresponding Author Rahul

Thakur, rahul.thakur.orp@chitkara.edu.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v6.i1s.2025.6620 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Generative Adversarial Networks, Digital Media

Education, Computational Creativity, AI Literacy, Human–AI Collaboration,

Ethical AI, Creative Pedagogy, Deep Learning in Education |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

With the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in creative education, a new age of digital education has been experienced. One of this extensive AI innovations is the Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), a revolutionary innovation that is currently transforming the conceptualization, production, and education of digital media. GANs were first presented by Ian Goodfellow and his co-authors in 2014 as two-network frameworks comprising of a generator and a discriminator, which are in an adversarial game Kaur et al. (2021). The generator tries to generate an artificial data which resembles the real world samples, and the discriminator tries to differentiate between actual and fake data. This antagonistic relationship generates outputs that tend to be visually realistic, and they can be applied to synthesizing images and animating, creating music, and creating 3D models. This ability in digital media education presents new creative, critical and cross-disciplinary learning opportunities Chen et al. (2021). Pedagogically, GANs are in line with constructivist learning and experiential education, which is built on active knowledge-building by way of experimentation and reflection. With the work with GANs, learners get their hands on the creative potential of AI systems, which is to know not only what they generate but also how they generate it Dorodchi et al. (2019).

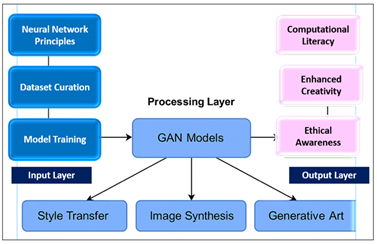

Figure 1

Figure 1 Conceptual

Framework of GAN Integration in Digital Media Education

Pedagogical implications of using GANs are not limited to creative production, but also to the acquisition of new cognitive set of skills. The students who are using generative AI gain hybrid skills that combine both technical and creative reasoning. They are taught to learn to interpret loss functions, manipulate latent spaces and learn to think about probabilistic behavior and are at the same time taught how to be sensitive to visual concepts and images Grebo et al. (2023). This conjoining breeds the next generation of the AI-weird producers capable of critically confronting technology as both producer and product as in Figure 1. Additionally, due to its collaborative character of GAN-based projects, peer-to-peer learning and reflective discourse as primary elements of higher-order educational outcomes are promoted. Another way that GANs can be used in digital media education is the improvement of human-machine collaboration. GANs are dialogic as opposed to traditional software tools that perform explicit user commands Ha and Eck (2017). The results are commonly unpredictable where students must interpret, refine and co-evolve ideas with the model. It is an interactive process just like in the case of creative improvisation where the end product is shaped by iteration and feedback. Consequently, learners become more resilient, flexible and have a better understanding of the creative process as a trade-off between control and emergence.

2. Literature Review

These networks in particular, digital media and creative arts, have moved beyond being technical artifacts, to creative tools and even cognitive proviencals. This development can be traced in the increasing number of publications, which place GANs as a technical architecture and a platform of aesthetic research.

1) Technical

Foundations and Creative Capabilities

GANs have since then evolved a lot since the original adversarial model. Different models like Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs), Conditional GANs (CGANs), and StyleGANs have improved the fact that it is possible to control and stylize the generated results and improve them Karras et al. (2020). Radford et al. (2016) proposed DCGANs, which provides a stable image architecture to produce high-quality images, and Karras et al. (2020) came up with StyleGAN, which allows manipulation of visual elements (like texture and lighting) through the fine-grained control.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Structure of GAN-Based Learning Activities |

||||

|

Activity

Type |

Tool

/ Model Used |

Duration |

Learning

Objectives |

Assessment

Focus |

|

GAN

Image Generation Workshop Kim et al. (2018) |

StyleGAN2,

DCGAN |

3

weeks |

Understanding

architecture, parameter tuning |

Technical

comprehension, output realism |

|

Style Transfer Project Lomas (2020) |

CycleGAN |

2 weeks |

Artistic experimentation and

creative synthesis |

Aesthetic originality |

|

Interactive

Art Installation Ali et al. (2019) |

RunwayML + Unity |

4

weeks |

Real-time

generative art and interaction |

Interdisciplinary

collaboration |

|

Ethics Debate / Reflection Li et al. (2019) |

Deepfake Analysis |

1 week |

Awareness of authenticity,

data bias |

Ethical reasoning, critical

thinking |

Table 1, Gives a brief description of the modules or workshops that are to be incorporated in the study. In the case of digital media education, these developments can be viewed as potent creative tools - students are able to explore their style transfer images to images (e.g., with Pix2Pix or CycleGAN), procedural content creation to game and animation. A number of scholars have highlighted the imaginative and intellectual aspects of GANs in art application. Such deviation within the educational context promotes the abstract ideas of creativity, authorship and randomness in students, correlating with the constructivist theories that appreciate experimentation and interpretation.

2) Pedagogical

Implications and Curriculum Integration

Successful curricular integrations have been described with the help of case studies. To give an example, Parsons School of Design and the Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU have already used GAN-based modules in courses on computational art and machine learning to be creative. Pre-trained networks, such as BigGAN and CycleGAN, were used by the students to create visual compositions and installations to interact with Oppenlaender (2022). The results of these applications indicate that students did not only become more technologically proficient, but also acquired critical awareness of the use of AI in cultural production. This kind of integration is an example of transdisciplinary pedagogy, in which computer science is taught in the context of creative and narrative and ethics.

3) Cognitive

and Aesthetic Perspectives

The thoughts and the ways of thinking associated with the interaction with GANs are not the same as those in the regular use of digital media. This process is similar to the improvisation in art and music, students come up with ideas, run them through the GAN, analyze the results and modify the parameters Johnson et al. (2018). These repetitive loops can raise the technical knowledge as well as the artistic instinct. The viewpoint poses new questions to media education: What is authorship in the case of distribution of creation between human and machine? What is the way to criticize an art created by statistical means? The answers to these questions help students develop a subtle concept of the posthuman aspects of digital creativity Lin (2023).

The future research should therefore aim at creating systematic pedagogical systems that would help to reconcile GAN education with learning goals in art, design, and media communication Hatwar et al. (2025). With the changing nature of digital media education in keeping with the pace of technological speed, these frameworks will be critical towards ensuring GANs are used in a responsible and effective way as instruments of artistic expression as well as of societal reflection.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework of the research was developed in order to research the ways in which Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) may be implemented into digital media education to increase creativity, technical literacy, and ethical awareness. The mixed methods approach was used, which involves qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis to present an in-depth view of both the learning outcomes and also the experiences gained. This method simplified the assessment of GAN-supported pedagogical interventions by both quantitative and qualitative outlooks in terms of cognitive, affective and ethical development. The study used an exploratory sequential design, as it first used a qualitative inquiry to determine the important themes associated with GAN application in creative education and then it was followed by quantitative assessment to substantiate the findings. The use of this design is due to the fact that the education area of GAN-based education is still relatively recent, and the first stage of concept exploration should be made prior to the application of the concept to the empirical generalization level. The qualitative stage implied using the focus group discussions, classroom observation, and semi-structured interviews with instructors and students in digital media programs that included the GAN-related coursework. The second quantitative phase utilized the tools of surveys and project evaluations, which helped to determine the degree to which exposure to GANs affected the production of creative works, the development of technical skills, and the ethical discourse. As the case studies, three educational institutions were selected:

1) A design school based on new media and computational art.

2) A university that has interdisciplinary media technology programs.

3) Digital animation and game design vocational institute. The institutes had implemented to the course content at least one GAN-based module within the past two academic years, which offered different contexts to study.

Phase -1] Participants and Sampling

The age range of the target audience to investigate Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in digital media education will be different based on the cognitive stages of learners, their technical preparedness, and their creative maturity. As powerful technologies based on deep learning and artificial intelligence, GANs, at the same time, possess enormous potential as creative tools that can be scaled to other levels of education.

1) Secondary

Education (Ages 15–18) — Introductory Exposure

On the high-school level, the concept of GANs may be presented as a part of STEM and creative-technology classes. The students of this age group may learn simplified applications like:

· Image preprocessing or style transfer with the help of AI through the use of readily available tools, such as RunwayML or DeepArt.

· Debates about such ethical concerns as deepfakes and media truthfulness.

· Hackathons with the fusion of art and simple AI.

Pedagogical Focus:

· Kinaesthetic illustration to mathematical profundity.

· Having intrigue in creativity about AI.

· The integration of the basics of digital ethics.

Learning Outcome: Understanding of the manner in which AI produces media and how the ethical duty is linked to digital production.

2) Undergraduate

Level (Ages 18–23) — Technical and Creative Integration

Undergraduate level students are cognitively mature enough and understanding of technical realities to interact with GAN architectures, code implementation and creative synthesis. Students can: ideally suited to such disciplines as digital media design, computer science, animation, or communication technology:

· Learn neural network elements and pre-processing of the data.

· Check on authentic content of real and synthetic.

Pedagogical Focus:

· Combining innovation and computer literacy.

· Not only should AI be encouraged to be used experimentally but also co-created.

· Integrating ethical courses dealing with bias and fake news.

3) Postgraduate and Research Level (Ages 23+)

At this stage, GANs will be a research and innovation instrument. The graduate and doctoral students will have an opportunity to study:

· New image, audio or video synthesis GAN architectures.

· Some of the fields where AI can be applied to creative workflows are film, gaming, or virtual reality.

· Art and machine learning and digital ethics Cross-disciplinary research.

Pedagogical Focus:

· Hypothetical knowledge and system modeling.

· New study and innovation in artistic AI.

· Policy, cultural impact and ethics analysis.

Learning Outcome: The Theory of Contributing to the scholarly discussion and developing new AI-driven creative frameworks.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Summarizes the Targe Age Group Data |

|||

|

Education

Level |

Age

Range |

Learning

Focus |

Outcomes |

|

Secondary |

15–18 |

Conceptual

understanding and ethics |

Awareness

and curiosity |

|

Undergraduate |

18–23 |

Technical and creative

integration |

AI literacy and design

skills |

|

Postgraduate |

23+ |

Research

and innovation |

Scholarly

contribution and applied creativity |

In the case of demography, the participants were diverse in terms of disciplines, such as graphic design, interactive media, sound design, and digital storytelling, to guarantee diversity in creative practice as well as technological orientation as outlined in Table 2. This diversity played an essential part in studying the effect that GANs produce on achievement in art and technology.

Phase -2] Data Collection Methods

The data collection was conducted in six months and comprised of three main parts which included classroom observation, structured project evaluation and post-intervention feedback.

1) Classroom

Observation:

Direct observations were done in GAN-based classes and workshops. The researcher also recorded teaching practices, interaction with students, group dynamics, and creative experimentation. Themes that were coded in field notes were curiosity, challenge, and reflective learning.

2) Project-Based

Assessment:

The students were given creative tasks with the use of GAN models (e.g., StyleGAN, CycleGAN, or DeepDream). All three projects were considered on three levels: aesthetic innovation, technical implementation, and ethical reflection. Learning performance was measured in terms of a rubric-based assessment (rated on a scale of 1-5), which allowed comparing it across institutions.

3) Surveys

and Interviews:

The changes on the student perception on AI creativity, technical confidence, and ethical understanding were quantified by pre- and post-course surveys. Likert scale items were used to measure the changes in the mindsets and the open ended responses provided qualitative information. The semi-structured interviews with the teachers were used to investigate pedagogical motivation, teaching issues, and observations of the student behavior.

The combination of these data sources underwent triangulation which made it strong and minimized the possible methodological bias. The quantitative measures provided objective indicators of performance, and the qualitative details provided put these indicators into perspective in the lived experience of teachers and students.

Phase -3] Analytical Framework

Data analysis was done in two phases- qualitative thematic analysis and quantitative statistical analysis.

Qualitative Analysis:

Inductive approach was applied in coding interview transcripts and observation notes. Themes were arranged in three general areas:

1) Pedagogical Adaptation: the ways in which teachers altered their curriculum and approaches to teaching in order to accommodate GANs.

2) Ethical Awareness: how the participants explained their knowledge of data bias, implications of deepfakes, and authorship issues.

The NVivo software was employed to determine the co-occurrence patterns between themes which enabled a comparison of institutions.

Quantitative Analysis:

The data collected in pre- and post-courses surveys were statistically tested on the basis of paired t-tests and ANOVA to examine the significance of the students that altered their self-reported skills and ethical awareness. Correlation analysis was carried out on project scores to inform about the relationships between technical mastery and creative originality. The findings were represented using bar charts and scatter plots in order to find out the trends in performance in the three study sites.

Phase -4] Reliability, Validity, and Ethical

Considerations

To provide reliability, the protocols of data collection were consistent in the different institutions. Each of the evaluators had the same project assessment rubric, and the inter-rater reliability tests were made to reduce the subjective scoring variance. The methodological triangulation which involved comparing survey data, project results and interview responses to support thematic consistency validated it. Pre-testing of survey instruments was undertaken in order to make them clear and relevant.

The ethical issues were considered as primary ones, as the research was focused on the AI-generated content. The participants had been informed about the data ownership, copyright, and consent in generative media issues. The datasets to be trained in GAN were all obtained in open-access repositories or produced by the participants to prevent any legal or ethical breaches. A participating university had to provide its Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, and as such, the research adhered to ethics.

Phase -5] Limitations of Methodology

Although the mixed-methods method offered holistic information, some weaknesses still existed. The sample size of the study is also varied, but it may not reflect the whole range of digital media education on the global level. This subjectivity in the case of self-reported measures and the high complexity of GAN projects hindered experimentation on resource-constrained systems. Furthermore, the rapid evolutional change of AI tools can make certain findings time-sensitive and it is necessary to update them regularly to avoid losing their pedagogical relevance.

The structure of methodology was formed in such a way that it was aimed at the balancing of the technical rigor and educational depth. The combination of the empirical evaluation and the reflective inquiry helps the study to embrace the complexity of the learning experience with GANs, including the acquisition of skills, the manifestation of creativity, and the advancement of ethics. The lessons found through this strategy form a ground upon which the learning generation of generative technologies can be assessed and their effect on digital media education can be anticipated in the pedagogical approaches of the future.

4. Results and Discussion

This research makes important contributions to the pedagogical, cognitive, and ethical aspects of introducing Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to digital media education. Using the mixed-methods framework, the results show that there is a complex change in the learning behavior of students, creative interaction, and ethical consciousness. Quantitative findings reveal a measurable result improvement in the areas of technical literacy and creative confidence and the qualitative analysis provides evidence of the development of reflective and interdisciplinary learning cultures. The statistical analysis of the post- and pre-course surveys proved the great improvement of the knowledge about GAN concepts and their use on the creative projects by the students. Mean self-reported technical proficiency score of the five-point scale rose by 2.8 to 4.3 using a paired t-test analysis (p < 0.01), which shows that learning outcomes were strong in all 3 institutions. There was also better neural network outputs and tuning parameter interpretation confidence among the students. Comparison of institutions in ANOVA depicted that the specific learning gains did not differ significantly implying that the efficiency of the GAN-based pedagogy was similar irrespective of the type of institutions or the resource level.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Summarizes the Post Evaluation Assessment Rubric |

||

|

Post-Test Mean |

||

|

GAN

Architecture Understanding |

2.7 |

4.4 |

|

Model Training and Parameter

Tuning |

2.9 |

4.2 |

|

Data

Preparation and Ethics Awareness |

2.5 |

4.0 |

|

Creative Application |

3 |

4.5 |

Aesthetic innovation and technical implementation were the highest scoring items in the assessment rubric in Table 3 with the average scores of 4.5 and 4.2 respectively. This reflects that the GAN-based activities were effective in inculcating both artistic testing as well as calculative ability. Interestingly, ethics reflection, with the lowest score in the mean of 3.8, reflected most of the improvement that was experienced between the beginning and end of the course. This implies that the more the students were involved with the technology the more they became sensitive to issues surrounding data ethics and authorship. Correlation analysis also showed that, there is a very strong positive correlation (r = 0.72) between technical proficiency and creative originality. Students that were more in control of GAN models were also more likely to create conceptually advanced artworks. This supports the assumption that technical control in generative systems can directly promote expression creativity- a dynamic that is hardly motivated in a conventional software-based learning space.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Qualitative Data Also Illuminated New Patterns of Cognitive Engagement |

|

|

Criterion |

Mean

Score |

|

Aesthetic

Innovation |

4.5 |

|

Technical

Implementation |

4.2 |

|

Conceptual

Depth |

4 |

|

Ethical Reflection |

3.8 |

|

Presentation

Quality |

4.3 |

Students got to know how to interpret GAN output as a form of algorithmic expression and not automation. This appreciation brought about deeper debates on agency of the machine, aesthetic will and boundary between humans and machines in creativity. The teachers observed that students gained greater degrees of metacognitive awareness- they started doubting the visual result, and also the framework, information, and training prejudices that supported the result as explained in Table 4. According to the instructors, this reflective awareness is one of the most important thinking results of AI-assisted education.

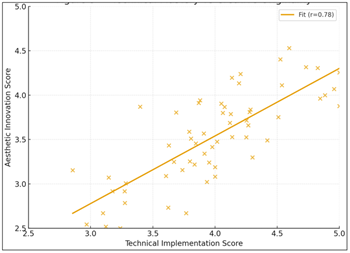

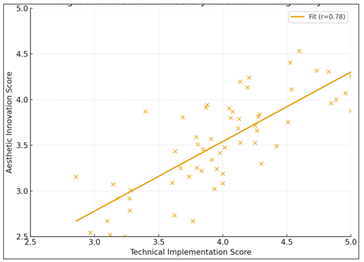

Figure 2

Figure 2 Correlation Between Technical Mastery and Creative Originality

The scatter plot represents the association among the scores of technical implementation (x-axis) and aesthetic innovation (y-axis) in 60 student projects. The data points are individual participants and the linear regression line exhibits a high degree of positive correlation (r = 0.72). The connection between these two facts validates that the greater the technical mastery, the more creative originality is observed. Students who showed more knowledge of model parameters, loss functions and dataset tuning generated more novel, conceptually consistent and pleasing outputs as represented in Figure 2. The visual ideological support of the plot is that creativity in AI age is computationally enhanced the more one knows how the model works, the more success one will have in its ability to express oneself. The fact that the distribution is rather close to the regression line confirms that the trend is consistent throughout the sample, which confirms the hypothesis that the notion of technical fluency strengthens, but does not limit artistic exploration in the process of learning digital media.

Table 5

|

Table 5 Summarizes the Score Values of Students Using GAN Model |

||

|

Student

ID |

Technical

Score |

Creativity

Score |

|

S01 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

|

S02 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

|

S03 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

|

S04 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

The findings also emphasize how project-based learning (PBL) can be helpful in enhancing creativity. Open ended, GAN, assignments, where students decided on their own themes and datasets, produced more novel results compared to hard and fast tasks as described in Table 5. This independent work developed ownership and an internal motivation, which is consistent with the self-determination theory of learning psychology. The fact that GAN applications can be used to create portraits and design clothes, as well as speculative architecture, made students free to match technical exploration with personal interests in creativity.

Figure 3

Figure 3 Pre-

and Post-Course Technical Proficiency Comparison

This above figure show the variation in the level of self-assessed proficiency level of the students prior to and after the course of GAN-integrated digital media. The four essential categories of learning, namely: the understanding of GAN architecture, training and tuning of the model, data preparation and awareness of ethics, and creative application, demonstrate significant increases in the post-course scores. The average scores of the students were 2.5 to 3.0 before the instruction, which showed that they did not know much about the neural architectures and data processing. The effect of the course increased greatly and it is between 4.0 and 4.5 in all the categories as shown in Figure 3. The highest rate of improvement was observed in "GAN architecture understanding" which contains the validity of scaffolding strategies applied by instructors. The score of creative application was also high, which additionally implies that students have learned not only to use technical skill, but to use GANs as a creative tool.

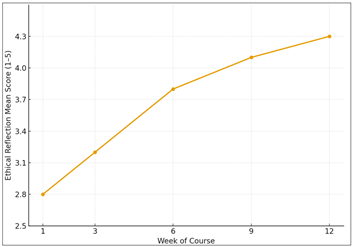

Figure 4

Figure 4 Ethical

Awareness Growth Over Time

The line chart follows the gradual increase in the scores of the ethical reflection over a 12-week GAN course. The students started with an average mark of 2.8, which demonstrates a poor understanding of information about the risks of data integrity, authorship, and misinformation. The gradual increase in the direction of 4.3 during week 12, shows a sharp development of ethical insight. Every spike is associated with certain class intervention- deepfakes debates, analysis of dataset bias, and reflective writing exercises as shown in Figure 4. The sharpest increase was during weeks 6-9 when the real-life case studies on media manipulation were introduced. At the end of the course, the learners showed not only theoretical knowledge but also, on a practical level, soundness in their ethical reasoning they demonstrated better self-reflection and compliance with sourcing data responsibly. This long term visualization brings out the importance of morally questioning the creative processes and operations themselves, instead of the facade level of morality.

Figure 5

Figure 5 Cross-Institutional

Comparison of Performance

The bar chart of results under the GAN curriculum involves

comparing the results of the GAN curriculum in three educational settings: a

Design School, a Technical University, and a Vocational Institute. The

institutions were rated based on three performance dimensions namely creative

innovation, technical implementation, and ethical reflection as represented in Figure 5. The Design School had

the highest scores of creative (4.7) which implied that the school had strength

in conceptual exploration and aesthetic depth. On the other hand, the Technical

University scored the highest in the field of technical implementation (4.6),

which demonstrates its analytical focus of model optimization and architecture

design. The Vocational Institute showed balanced scores in all the areas which

means that the modular, practic based pedagogy was

effective in incorporating creativity and technical literacy in a framework.

The comparative visualization demonstrates that there are institutional

contexts that affect the proportion of creative and computational consequences

but GAN-based education is still universally applicable in promoting innovation.

5. Conclusion and Future Work

As demonstrated in this paper, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) increasingly bring about a new era within the sector of digital media education by integrating both the areas of creative exploration and computational intelligence. The use of GANs in classes has transformed learners into another kind of student who is no longer a passive software consumer, but a co-creator, possessing an artistic vision and an algorithmic component to the logic. The quantitative findings showed the dramatic increase of technical literacy, creative innovation, and the understanding of ethics, and the qualitative results showed the positive improvement of such concepts as curiosity and reflection and collaboration. Instead, students were trained to believe that GANs are boosters and not replacements of innovation, thought-provoking experimentation, and flexibility and critical thinking. Theoretically, as a pedagogic aspect, the paper targets the shift to AI-fluent creative schooling, where design thinking and coding literacy co-exist. Learning environments based on GAN also facilitate the nurturing of the interdisciplinary approach which involves art, design, and computation synthesized into practice. Educators become the instructors of exploration enabling them to assist in technical comprehension and provoke moral cogitation. It is a hybrid way of learning that is creating a new generation of creators who are conscious of not only the mechanics but also the implications of artificial creativity. Another outcome, ethical awareness, also turned out to be quite significant, since students demonstrated improved knowledge of the topic of bias, authorship, and misinformation thanks to an orderly reflection and discussion. Despite these encouraging results, problems still remain. GANs are expensive, the faculty strengths are not as wide, and AI-generated content is morally controversial, which is a barrier to its scale usage. The sustainable realization involves institutional commitment towards technical infrastructure and ethics governing systems. The constructive measures of the future research must be founded on the establishment of the standardized pedagogic models of GAN learning, adaptive learning space of evaluation of skill levels of pupils, and longitudinal research of professional outcomes. GANs will play a critical role in the future to produce responsible digital creators who can code, critique and collaboratively create intelligently. The innovative technologies of diffusion models, AR/VR, and multimodal AI with the usage of GANs will expand the possibilities of creativity and have to be more ethically literate. Lastly, GAN-based education is one such instance of the paradigm that technology is a kind of thinking, creatively, morally reasoning etc. Inclusion of GANs into the digital media programmes, teachers do not merely prepare students in mastering the artificially intelligent tools, but will also have the capacity to shape the culture, aesthetics and ethics that is embodied by the artificial intelligence in the future. GANs are thus innovational tools and instruments of rebuilding the basics of innovative learning in the 21st century reality.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ali, S., Payne, B. H., Williams, R.,

Park, H. W., and Breazeal, C. (2019). Constructionism, Ethics,

and Creativity: Developing Primary

and Middle School Artificial

Intelligence Education. In Proceedings of the

International Workshop on Education in Artificial

Intelligence K–12

Chen, F. J., Zhu, F., Wu, Q. X., Hao, Y. M., Wang, E. D., and Cui, Y. G. (2021). A Review of Generative Adversarial Networks and their Applications in Image Generation. Journal of Computer Science, 44(2), 347–369.

Dorodchi, M., Al-Hossami, E., Benedict, A., and Demeter, E. (2019). Using Synthetic Data Generators to Promote Open Science in Higher Education Learning Analytics. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) (pp. 4672–4675). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData47090.2019.9006475

Grebo, B., Krstulović-Opara, L., and Domazet, Z. (2023). Thermal to Digital Image Correlation Image to Image Translation with Cyclegan and Pix2Pix. Materials Today: Proceedings, 93, 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.219

Ha, D., and Eck, D. (2017). A Neural Representation of Sketch Drawings. arXiv.

Hatwar, L. R., Pohane, R. B., Bhoyar,

S., and Padole, S. P. (2025). Mathematical Modeling on Decay of Radioactive Material

Affects Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Research and Development

Management Review, 14(1), 180–182.

Johnson, J., Gupta, A., and Fei-Fei, L. (2018). Image Generation from Scene Graphs. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (pp. 1219–1228).

Karras, T., Laine, S., Aittala, M., Hellsten, J., Lehtinen, J., and Aila, T. (2020). Analyzing and Improving the Image Quality of StyleGAN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00813

Kaur, D., Sobiesk, M., Patil, S., Liu, J., Bhagat, P., Gupta, A., and Markuzon, N. (2021). Application of Bayesian Networks to Generate Synthetic Health Data. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(4), 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa303

Kim, H., Garrido, P., Tewari, A., Xu, W., Thies, J., Niessner, M., Perez, P., Richardt, C., Zollhöfer, M., and Theobalt, C. (2018). Deep Video Portraits. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 37(4), Article 163. https://doi.org/10.1145/3197517.3201283

Li, B., Qi, X., Lukasiewicz, T., and Torr, P. H. S. (2019). Controllable Text-To-Image Generation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 32).

Lin, E. (2023). Comparative Analysis of Pix2Pix and CycleGAN for Image-To-Image Translation. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology, 39, 915–925. https://doi.org/10.54097/hset.v39i.6676

Lomas, N. (2020, August 17). Deepfake Video App Reface is Just Getting Started on Shapeshifting Selfie Culture. TechCrunch.

Machine Learning for Artists. (2016). Machine Learning for Artists.

Oppenlaender, J. (2022). The Creativity of Text-To-Image Generation. In Proceedings of the International Academic Mindtrek Conference (pp. 192–202). https://doi.org/10.1145/3569219.3569352

Wang, Z., She, Q., and Ward, T. E. (2021). Generative Adversarial Networks in Computer Vision: A Survey and Taxonomy. ACM Computing Surveys, 54(2), Article 42. https://doi.org/10.1145/3439723

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2024. All Rights Reserved.